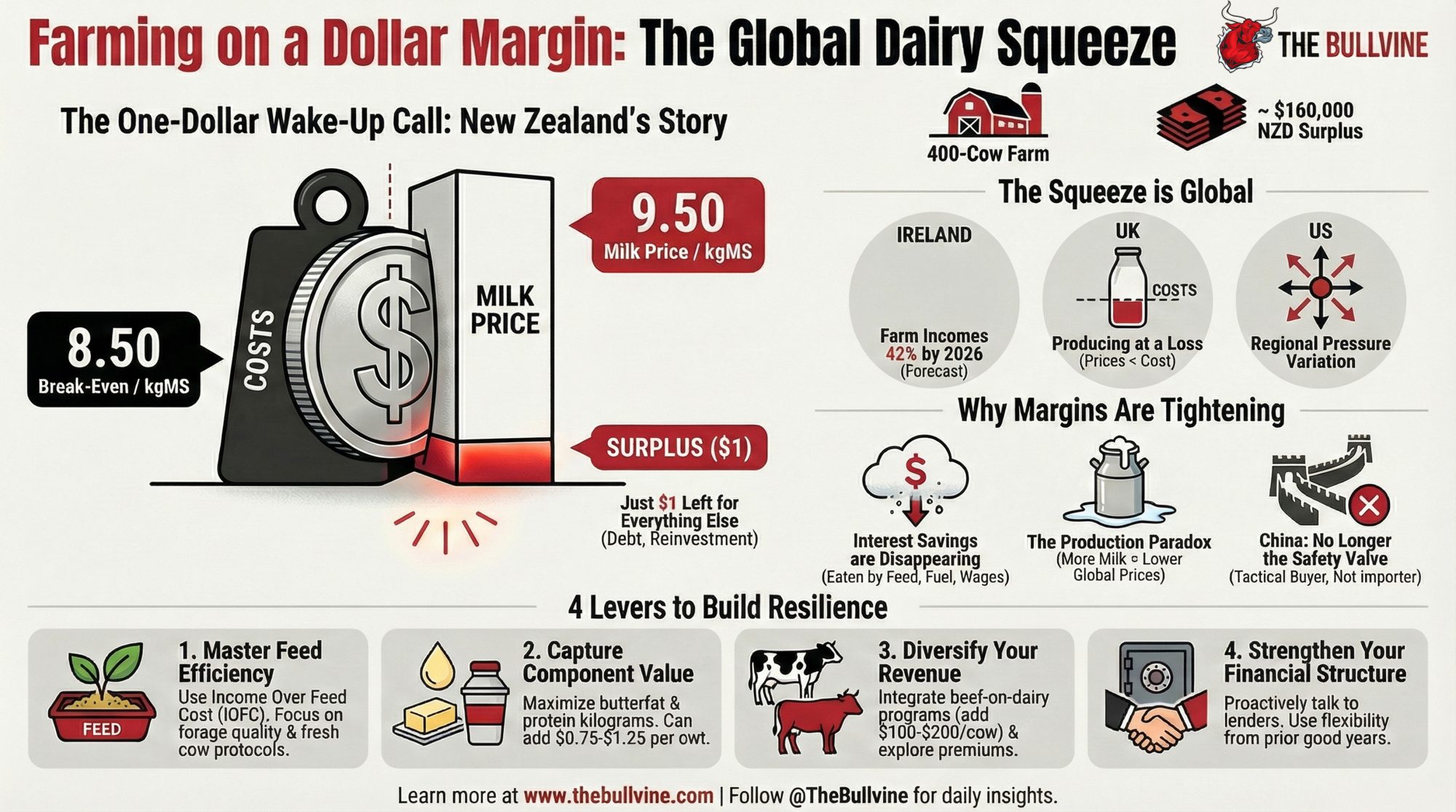

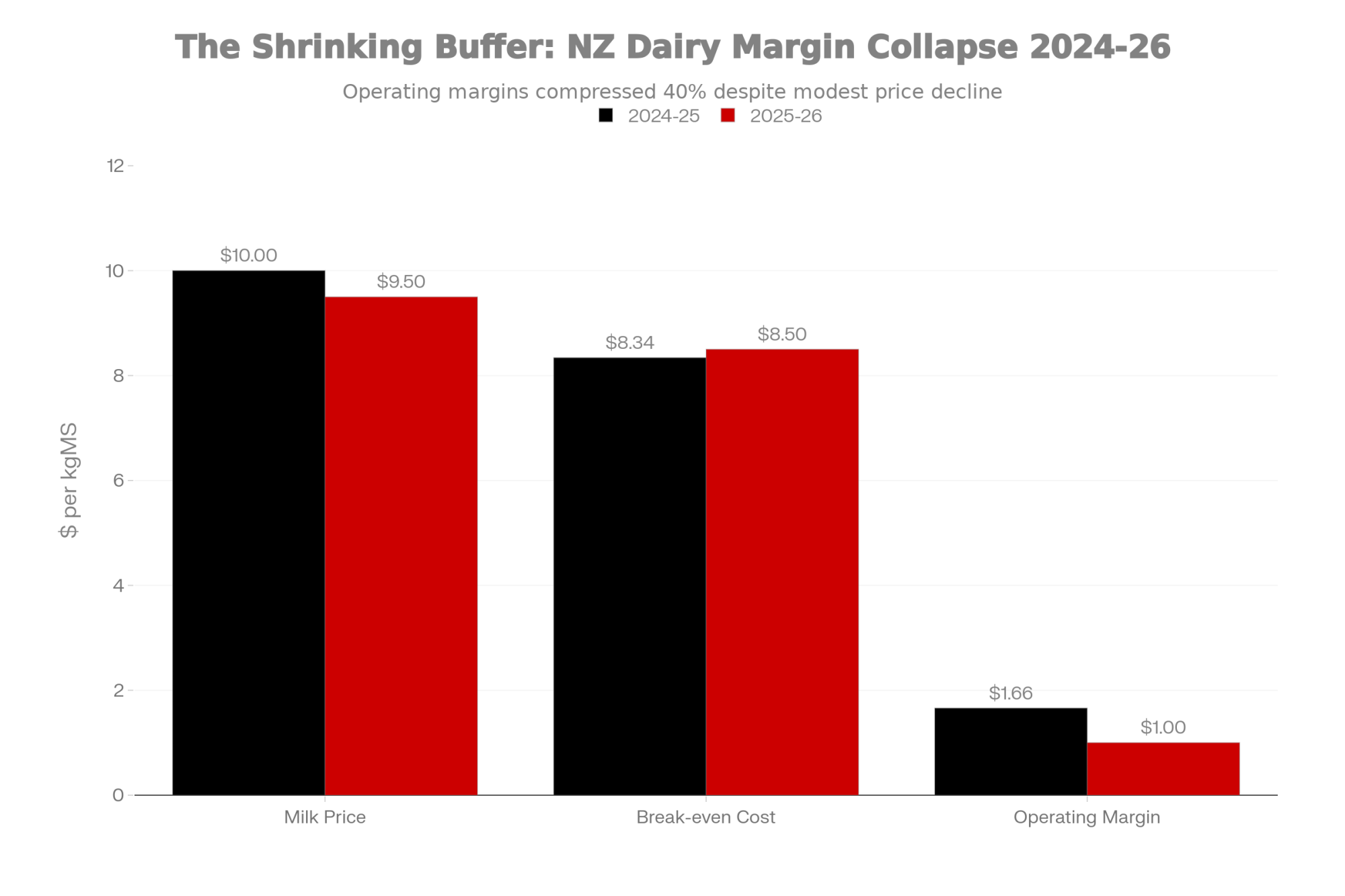

A $9.50 milk price sounds great—until you see the $8.50 break-even. NZ’s one-dollar margin is a wake-up call for dairy farmers everywhere.

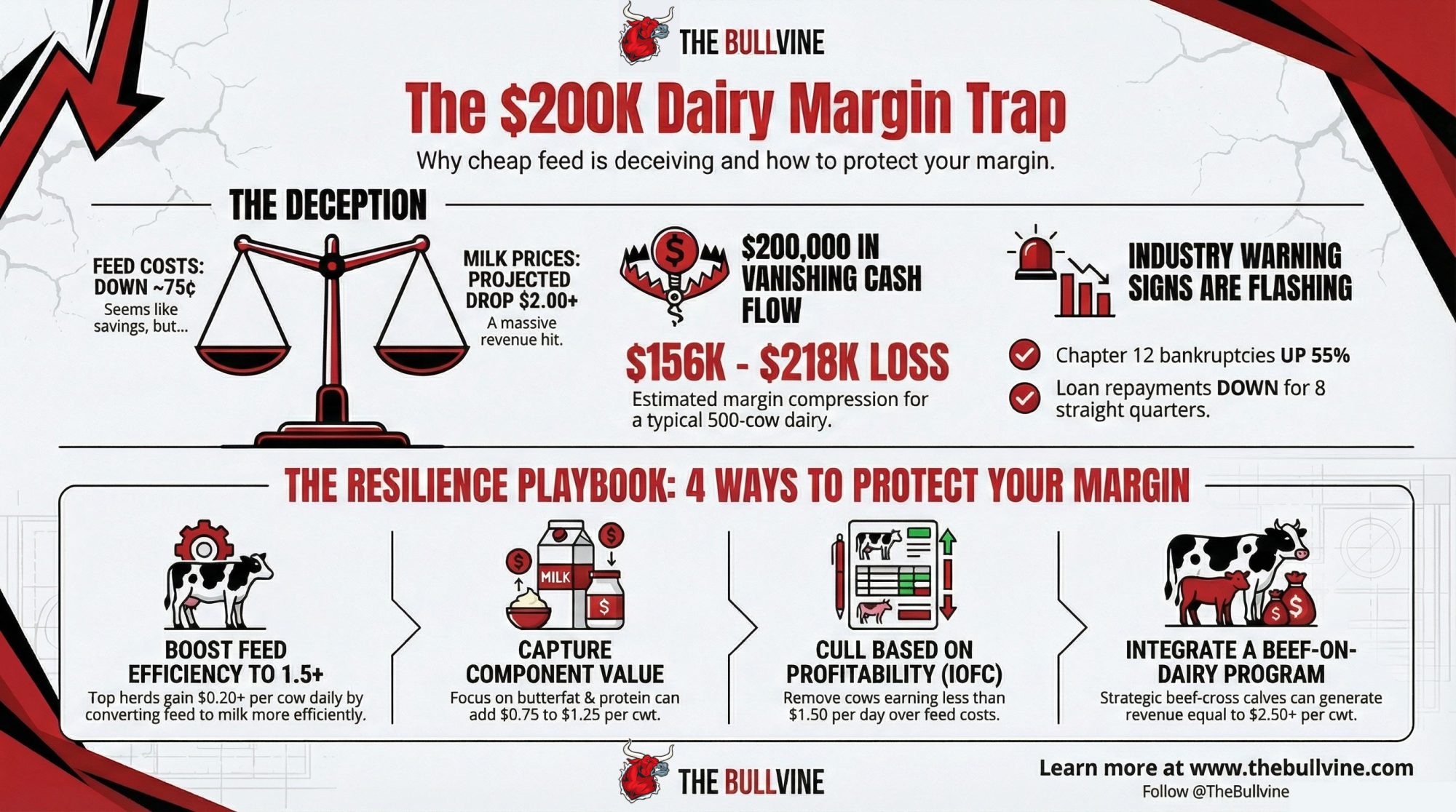

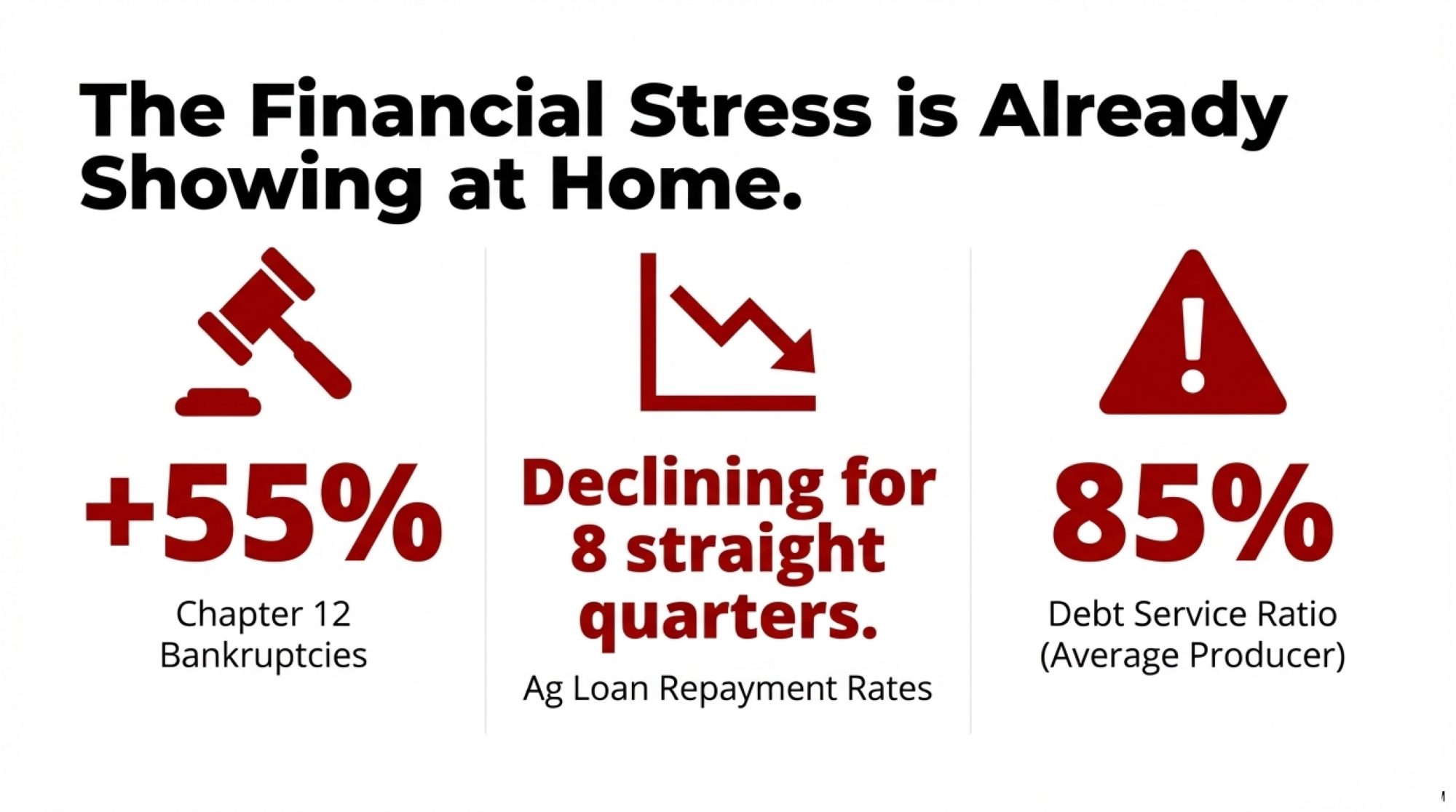

Executive Summary: When the world’s lowest-cost milk producers are farming on a dollar of margin, that’s a wake-up call for dairy everywhere. New Zealand’s December 2025 numbers: $9.50/kgMS milk price, $8.50 break-even, one dollar left for debt, drawings, and reinvestment. They’re not alone. Teagasc projects Irish dairy incomes dropping 42% in 2026. UK farmgate prices have fallen below production costs. Rabobank calls global output growth ‘stunning’—the very oversupply compressing margins worldwide. And China’s shift from aggressive importer to tactical buyer has removed the demand safety valve the industry once counted on. The old formula—high prices equal comfortable margins—no longer holds. The farms that make it through will be those building resilience now: feed efficiency, component focus, diversified revenue, right-sized debt. Not growth for growth’s sake. Strategic survival.

When the world’s lowest-cost milk producers are working on about one dollar of operating margin per kilogram of milk solids, that’s worth every dairy farmer’s attention.

That’s exactly where New Zealand finds itself heading into 2026.

Here’s what makes this relevant beyond the Pacific: it’s essentially a real-time stress-test of the global dairy model. From Wisconsin freestalls to Irish grass paddocks to Canterbury’s irrigated pastures, the underlying question is the same.

If New Zealand’s efficient pasture systems can’t maintain comfortable margins at these milk prices, what does that mean for the rest of us?

The narrative has shifted. It’s less about waiting for the next price spike and more about adapting to a new reality—one defined by persistent cost pressure, cautious global buyers, and markets that recover more slowly than they used to.

Understanding the One-Dollar Margin

DairyNZ’s December 2025 Economic Update paints a clear picture.

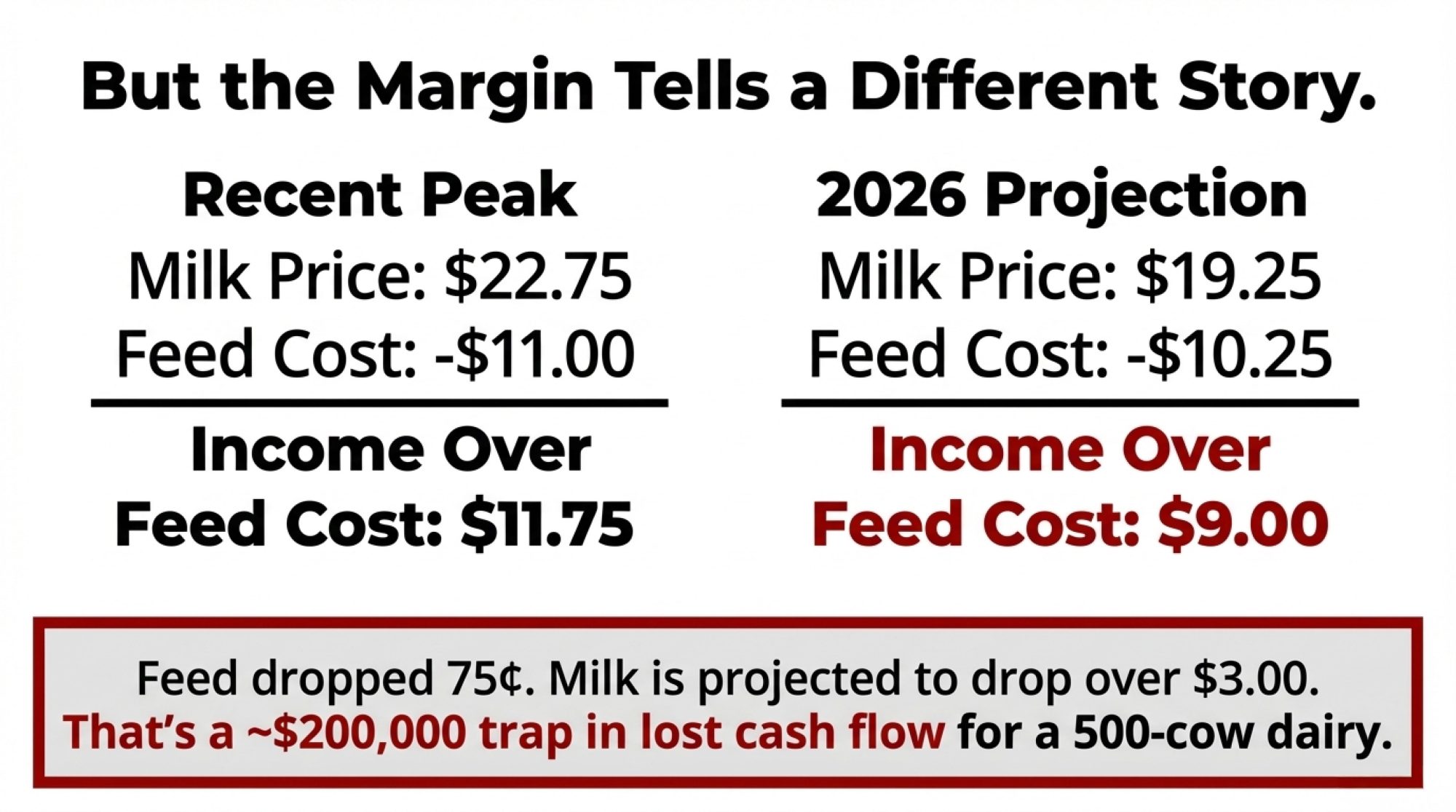

Farm working expenses have climbed 16 cents to $5.83 per kgMS. Meanwhile, Fonterra revised its 2025-26 farmgate milk price forecast down to a midpoint of $9.50 per kgMS—a notable drop from the earlier $10.00 projection.

DairyNZ puts the break-even milk price for an average reference farm at around $8.50 per kgMS.

That leaves roughly a dollar per kgMS as operating surplus. And that’s before capital repayments, family drawings, or any reinvestment.

| Metric | 2024-25 Season | 2025-26 Season | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk Price ($/kgMS) | $10.00 | $9.50 | -$0.50 |

| Break-even Cost ($/kgMS) | $8.34 | $8.50 | +$0.16 |

| Operating Margin ($/kgMS) | $1.66 | $1.00 | -$0.66 |

| Farm Working Expenses ($/kgMS) | $5.67 | $5.83 | +$0.16 |

| Interest Costs ($/kgMS) | $1.46 | $1.11 | -$0.35 |

Tracy Brown, DairyNZ’s chair and herself a Waikato dairy farmer, offered some measured perspective in their December update: “Profit is still on the table, but the margin gap has clearly tightened, and that means every spending decision on farm needs a harder look.”

That’s a statement worth sitting with.

What This Looks Like on a Real Farm

Think about a fairly typical New Zealand herd—400 cows producing 400 kgMS each. That gives you 160,000 kgMS for the season.

At $9.50 per kgMS, gross milk revenue comes to about $1.52 million NZD. With a break-even point of around $8.50, core operating costs consume roughly $1.36 million.

That leaves approximately $160,000 NZD of operating surplus.

On paper, that’s profit. But reality includes broken gates, aging tractors, and family obligations. The buffer is much thinner than the headline suggests.

I recently spoke with a consultant who works across both New Zealand and Australian operations. His observation: for a 200-cow farm, that surplus might only be $80,000 NZD before tax and drawings. For a 2,000-cow operation, you’re looking at roughly $800,000—but spread across substantially higher fixed costs and larger teams.

| Farm Size | Production (kgMS) | Gross Revenue | Operating Costs | Operating Surplus | Margin Per Cow |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 cows | 80,000 | $760,000 | $680,000 | $80,000 | $400 |

| 400 cows | 160,000 | $1,520,000 | $1,360,000 | $160,000 | $400 |

| 2,000 cows | 800,000 | $7,600,000 | $6,800,000 | $800,000 | $400 |

The ratio matters more than the headline number. Whether you’re milking 200 or 2,000, everyone’s working with a narrower buffer.

The Takeaway: A $9.50 milk price sounds strong. But with $8.50 break-evens, you’re farming on a dollar of margin—and that dollar has to cover everything else.

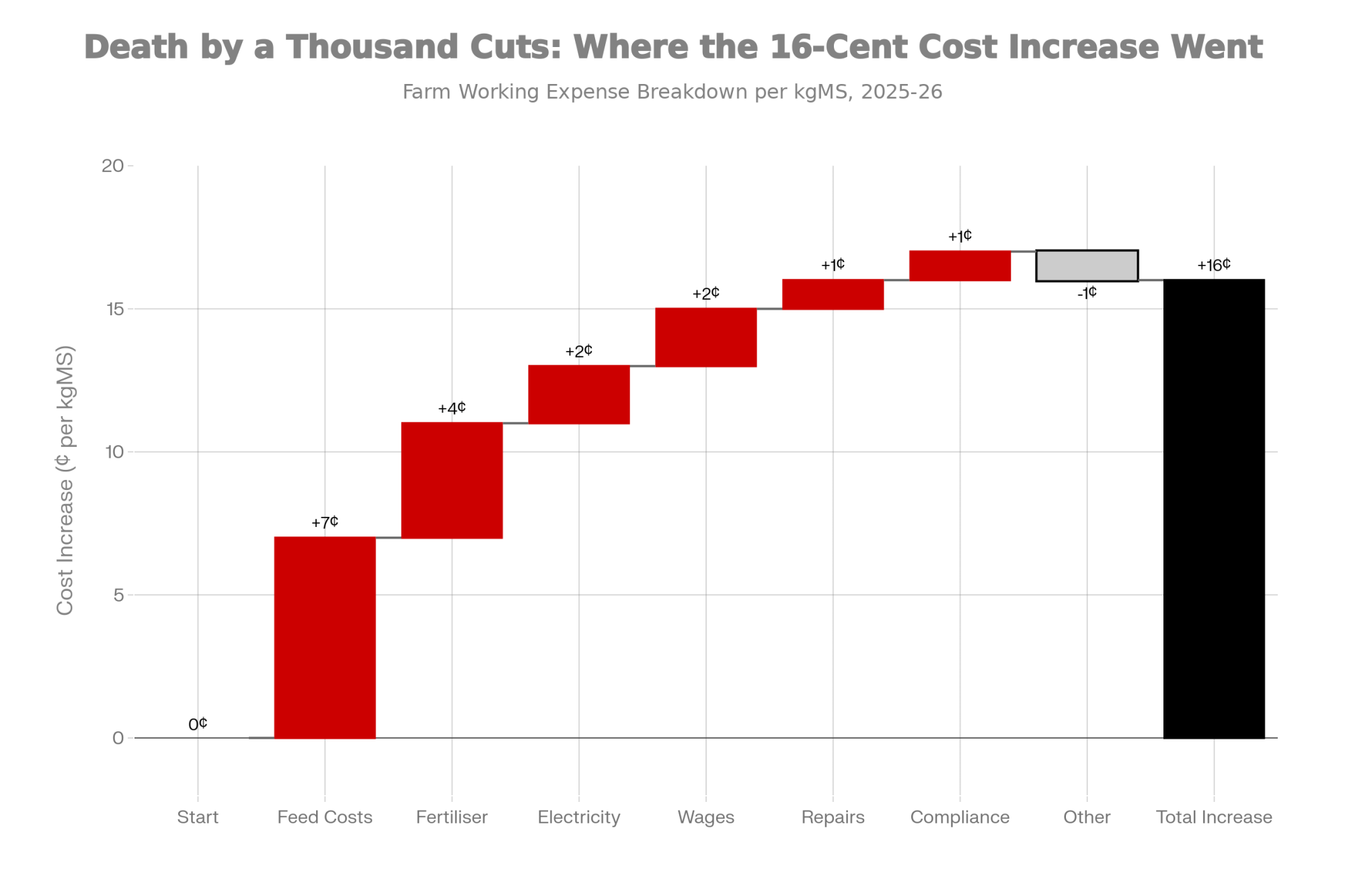

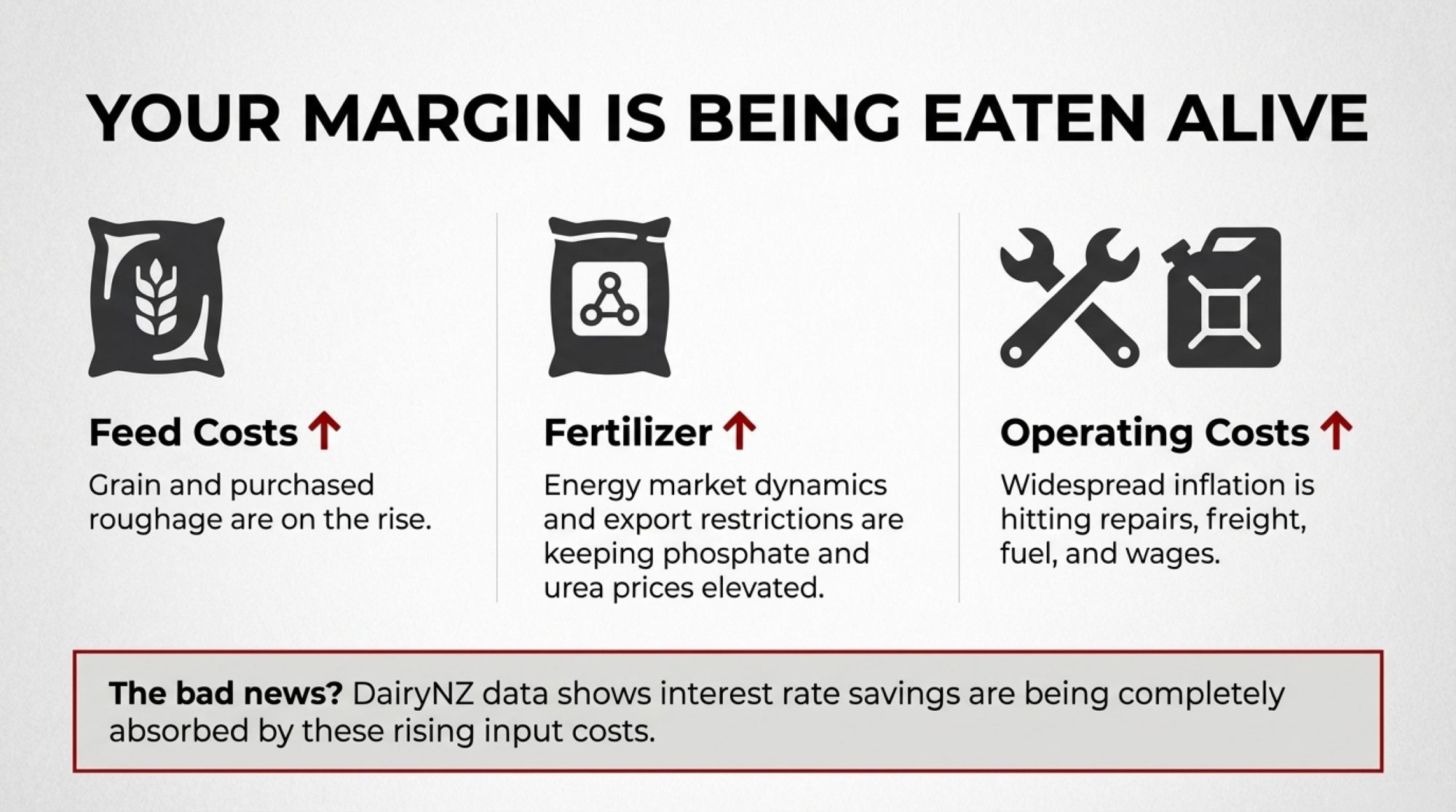

Tracing the Cost Increases

Where exactly did those 16 cents go? Understanding the drivers makes them easier to address.

DairyNZ’s Econ Tracker identifies three primary contributors.

| Cost Category | Increase (¢/kgMS) | 400-Cow Farm Impact | Controllability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feed Costs | +7¢ | +$11,200 | Medium – Nutrition strategy |

| Fertiliser | +4¢ | +$6,400 | Low – Global commodity |

| Electricity/Irrigation | +2¢ | +$3,200 | Low – Fixed infrastructure |

| Wages | +2¢ | +$3,200 | Low – Labour market |

| Repairs/Maintenance | +1¢ | +$1,600 | Medium – Defer vs invest |

| Compliance | +1¢ | +$1,600 | None – Regulatory |

| Other Operating | -1¢ | -$1,600 | Variable |

| TOTAL | +16¢ | +$25,600 | — |

Feed costs have risen meaningfully year-on-year across most categories. Palm kernel has been somewhat more stable, but grain and purchased roughage have risen noticeably.

Fertiliser continues to pressure budgets. Phosphate and urea prices remain elevated, driven by energy market dynamics and export restrictions from major suppliers. Teagasc’s Outlook 2026 suggests costs will climb further as the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism takes effect.

Other operating costs—repairs, freight, wages, fuel, compliance—have all experienced inflation.

The encouraging news? DairyNZ reports that interest costs are easing. Payments are forecast to drop about 35 cents to $1.11 per kgMS for 2025-26.

The catch? Those interest savings are largely offset by increases elsewhere. The budget might show relief on one line, but feed, fertiliser, and operating costs are absorbing it.

For a 200-cow farm, this might mean choosing between replacing an ageing parlour component or making do with repairs. On a 2,000-cow dry-lot operation, it could be the difference between upgrading a feed mixer or deferring that decision another year.

The Takeaway: Feed and fertiliser are eating your interest rate savings before you ever see them.

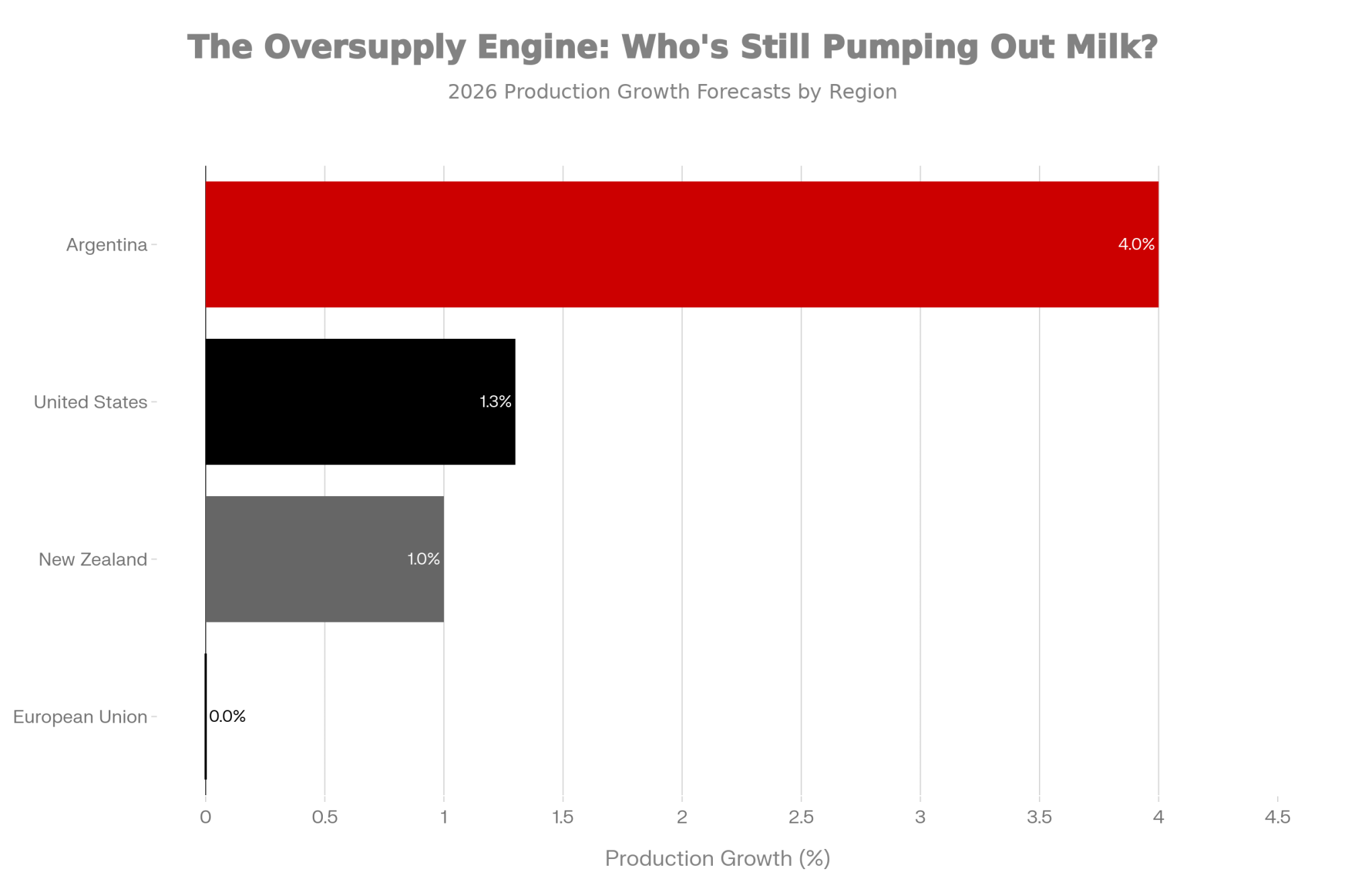

The Production Paradox

This is where the situation becomes counterintuitive.

New Zealand is currently in its spring flush. DairyNZ reports national milk collections running about 3.4% ahead of last season, with August and October 2025 volumes among the highest on record.

South Island production in October was up 5.7% year-on-year. Customs data shows palm kernel imports are up significantly—a clear indicator that farmers leaned into purchased feed to boost production.

Why does this matter? Because the same pattern is playing out across multiple dairy regions simultaneously.

I’ve been following similar trends in US and European coverage. Where corn or by-products are relatively affordable, there’s considerable temptation to push cows harder to maintain cashflow. Especially when fixed obligations don’t adjust downward just because your milk price does.

At the individual farm level, this appears entirely rational. If you’ve already invested in the parlour, the effluent system, and the bank financing, pushing a few more kilograms through spreads those fixed costs.

But collectively? When New Zealand, the US, Ireland, and parts of Europe all make that same calculation simultaneously, you end up with what Rabobank’s December 2025 commentary described as “stunning” global output growth.

| Region | 2026 Growth Forecast | Impact on Global Supply |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | +4.0% | Aggressive expansion continues |

| United States | +1.3% | Steady growth despite tight margins |

| New Zealand | +1.0% | Spring flush pushing volumes |

| European Union | 0.0% | Only major exporter hitting brakes |

That additional milk is precisely why price forecasts have moderated.

A Midwest producer I spoke with recently put it simply: “We’re not trying to grow anymore—we’re trying to survive long enough to see the other side.”

The Takeaway: What makes sense on your farm might be making things worse for everyone—including you.

Regional Perspectives

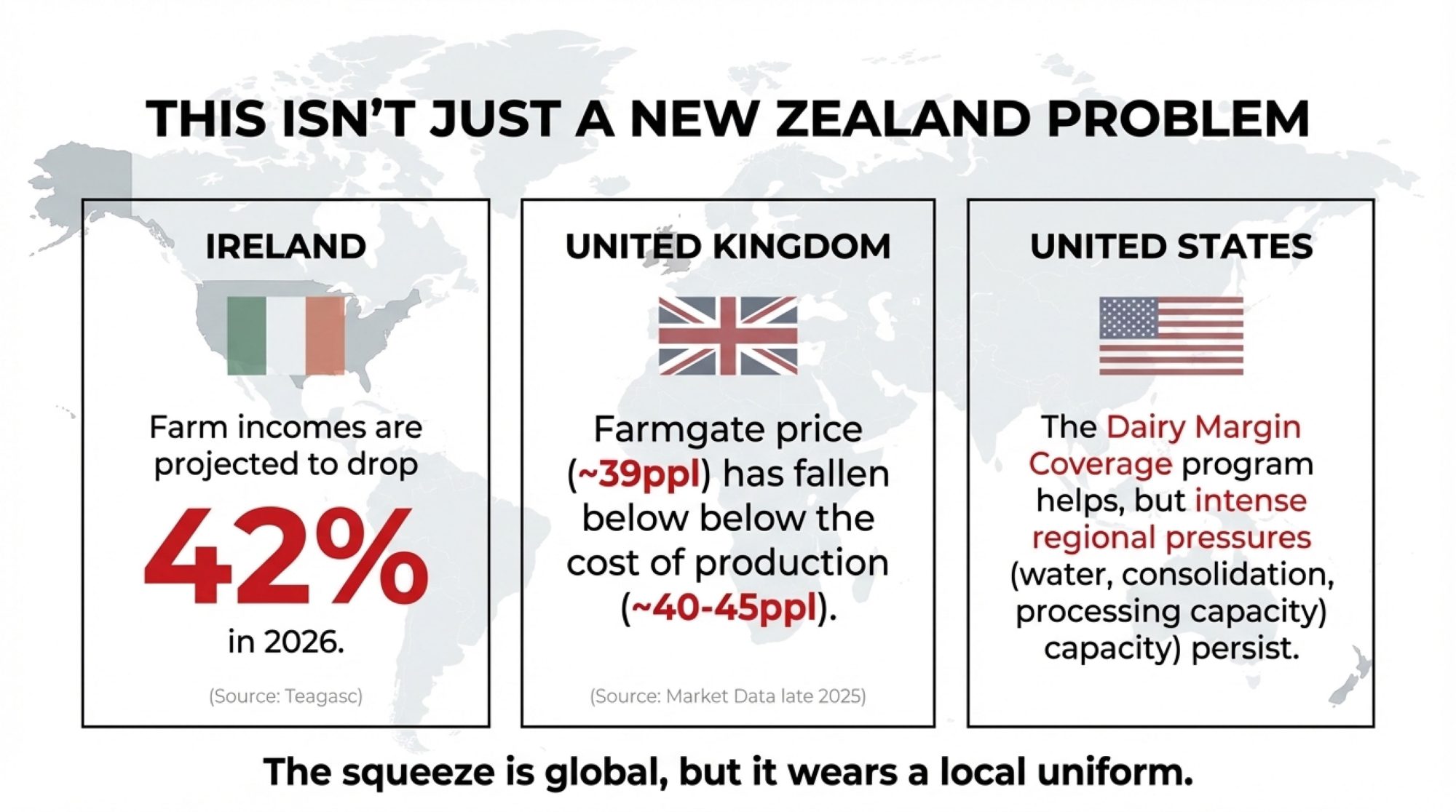

New Zealand’s experience offers the clearest current signal. But similar pressures are emerging across other major dairy regions.

| Region | Current Margin (2025) | 2026 Forecast | Key Pressure Point | Competitiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Zealand | +$1.00/kgMS | Tight ($0.80-1.00) | Feed & fert eating savings | High — Pasture based |

| Ireland | €0.115/L | Severe (-45%) | Butter price collapse | Medium — Scale challenges |

| United Kingdom | Below cost (38.5p/L) | Further pressure | Commodity liquid pricing | Low — High costs |

| United States (DMC) | Above $9.50/cwt | Stable (low feed) | Production growth | Variable — Regional |

| European Union | Squeezed — varied | Contraction likely | China probe uncertainty | Medium — Policy support |

Ireland: Preparing for a Correction

Teagasc’s Outlook 2026 projects that average Irish dairy farm incomes could decline by approximately 42% in 2026. That would take the average income from an estimated €137,000 this year to around €80,000.

Their baseline anticipates milk prices moderating from the high-40s cent per litre range back toward approximately 42 cents.

At 11.5 cents per litre, the average dairy net margin in 2026 is forecast to be down 45% from 2025 levels.

For a 70-hectare, 100-cow family farm, cash surplus after drawings and loan repayments could drop from around €80,000 to closer to €45,000.

That’s manageable if the debt is moderate. For operations that expanded aggressively, the adjustment will be sharper.

The UK: Below-Cost Production

Recent market data shows that farmgate milk prices have fallen below full production costs for many operations.

As of late 2025, Arla’s conventional price sits around 39.21 pence per litre. Müller’s Advantage price drops to 38.5ppl from January 2026.

Industry estimates place all-in production costs closer to the 40-45ppl range.

The picture varies by contract type. Producers on cheese or retailer-aligned arrangements often fare better. But in the commodity liquid segment, some operations are producing milk at a level below full economic cost.

Processors have responded by shifting toward component-based and fixed-volume contracts. Retailers continue to prioritise competitive shelf prices, putting pressure on producers’ margins.

The US: Regional Variations

The American experience differs due to policy structure—and substantial regional variation.

The Dairy Margin Coverage programme has provided meaningful support. The University of Wisconsin Extension reports that through the first ten months of 2023, DMC distributed over $1.27 billion in indemnity payments. That averaged approximately $74,453 per enrolled operation, with around 17,059 dairy operations participating.

But the experience varies dramatically by region.

In California, water costs and environmental compliance add layers of expense that Midwest operations don’t face. Wisconsin operations are navigating processor consolidation and volatility in the cheese market. Northeast producers face declining fluid milk demand and processing capacity constraints.

Larger US herds—1,000 cows and above—are increasingly relying on scale economies and diversified revenue streams. Beef-on-dairy programmes, heifer development, and energy projects are becoming standard.

The Takeaway: The squeeze is global, but every region has its own version. Know your local dynamics.

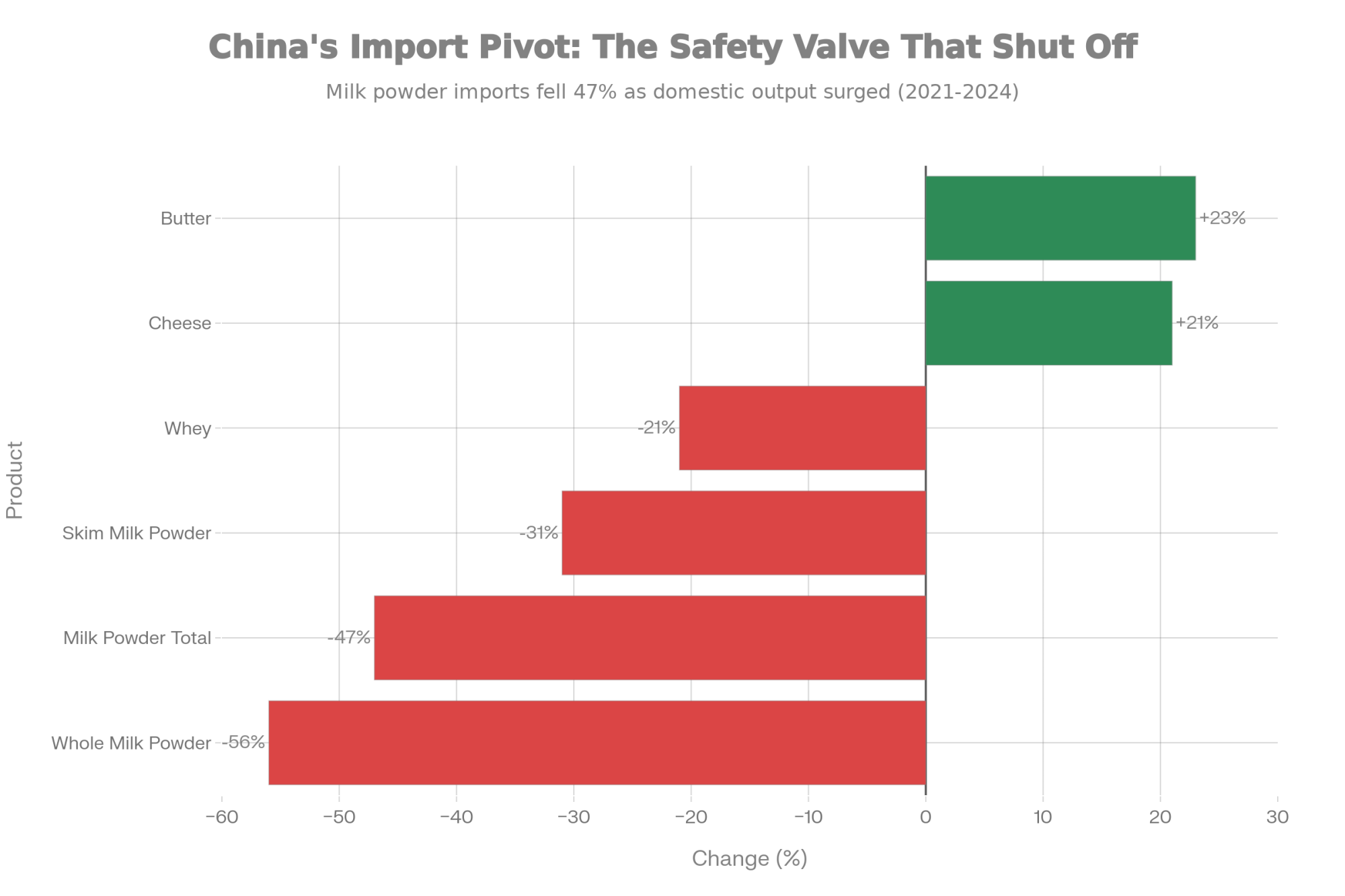

The China Factor

For two decades, much of dairy’s long-term optimism rested on a straightforward assumption: China would continue buying more.

That assumption deserves recalibration.

New Zealand Treasury’s 2024 dairy exports analysis, Rabobank’s global outlooks, and trade reports identify three meaningful shifts.

| Product Category | 2021 Imports (MT) | 2024 Imports (MT) | Change | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Milk Powder | 1,680,000 | 740,000 | -56% | Domestic production surge |

| Milk Powder (Total) | 2,580,000 | 1,360,000 | -47% | Structural decline |

| Skim Milk Powder | 900,000 | 620,000 | -31% | Domestic substitution |

| Whey | 480,000 | 380,000 | -21% | US tariff impact |

| Cheese | 140,000 | 170,000 | +21% | Foodservice growth |

| Butter | 110,000 | 135,000 | +23% | Bakery sector expansion |

Domestic production has expanded substantially. China has invested heavily in large-scale dairy operations. This is structural import substitution, not a temporary measure.

Per-capita consumption growth has moderated. Dairy consumption continues trending upward, but at slower rates than during the expansion years. The steepest part of the adoption curve appears behind us.

Purchasing behaviour has become tactical. Chinese buyers now step back when prices strengthen and increase purchases when value emerges—rather than consistently supporting auctions.

China remains a vital market. But it’s no longer the automatic release valve that absorbs surplus production.

The Takeaway: Don’t count on China to bail out oversupply anymore. That era is over.

What Farmers Are Actually Doing

When margin discussions move from conferences to kitchen tables, what are producers actually changing?

Managing Through Feed

In New Zealand, palm kernel imports are up significantly. Many farmers chose to push production while payout expectations remained near $10/kg MS.

Similar decisions are playing out in US operations where corn and by-products remain relatively affordable.

The logic is straightforward: when principal payments and family expenses don’t flex with milk price, spreading fixed costs across more production can appear to be the only short-term lever.

Strengthening Balance Sheets

New Zealand’s Ministry for Primary Industries notes that some farmers used the strong 2021-2023 payouts to reduce debt rather than adding infrastructure.

That decision is looking increasingly prudent.

On a 200-cow farm, this might translate to directing an extra $20,000 annually toward debt reduction rather than equipment upgrades. On a 2,000-cow operation, it could mean restructuring short-term facilities into longer-term arrangements.

Diversifying Revenue

Beef-on-dairy has become mainstream. Industry analyses suggest crossbred calves can add $100-200 per cow annually, depending on local markets.

Sustainability-linked premiums are emerging as processors develop payment structures tied to documented environmental outcomes.

Even modest additional revenue streams—$50,000-$100,000 annually on a mid-sized operation—can make a meaningful difference when the milk cheque alone isn’t covering the spread.

The Takeaway: Smart operators aren’t just cutting costs. They’re restructuring debt and finding new revenue.

| Strategy | Short-Term Cashflow | Margin Impact | Risk Level | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Push Production (Palm Kernel) | Improved | $0.85/kgMS | High — Adds to oversupply | High debt, large scale |

| Cut Costs Aggressively | Preserved | $1.15/kgMS | Medium — Quality risks | Medium farms, low debt |

| Maintain Status Quo | Squeezed | $1.00/kgMS | High — Thin buffer | No flexibility |

| Reduce Debt First | Reduced | $1.00/kgMS | Low — Future flexibility | Strong balance sheet |

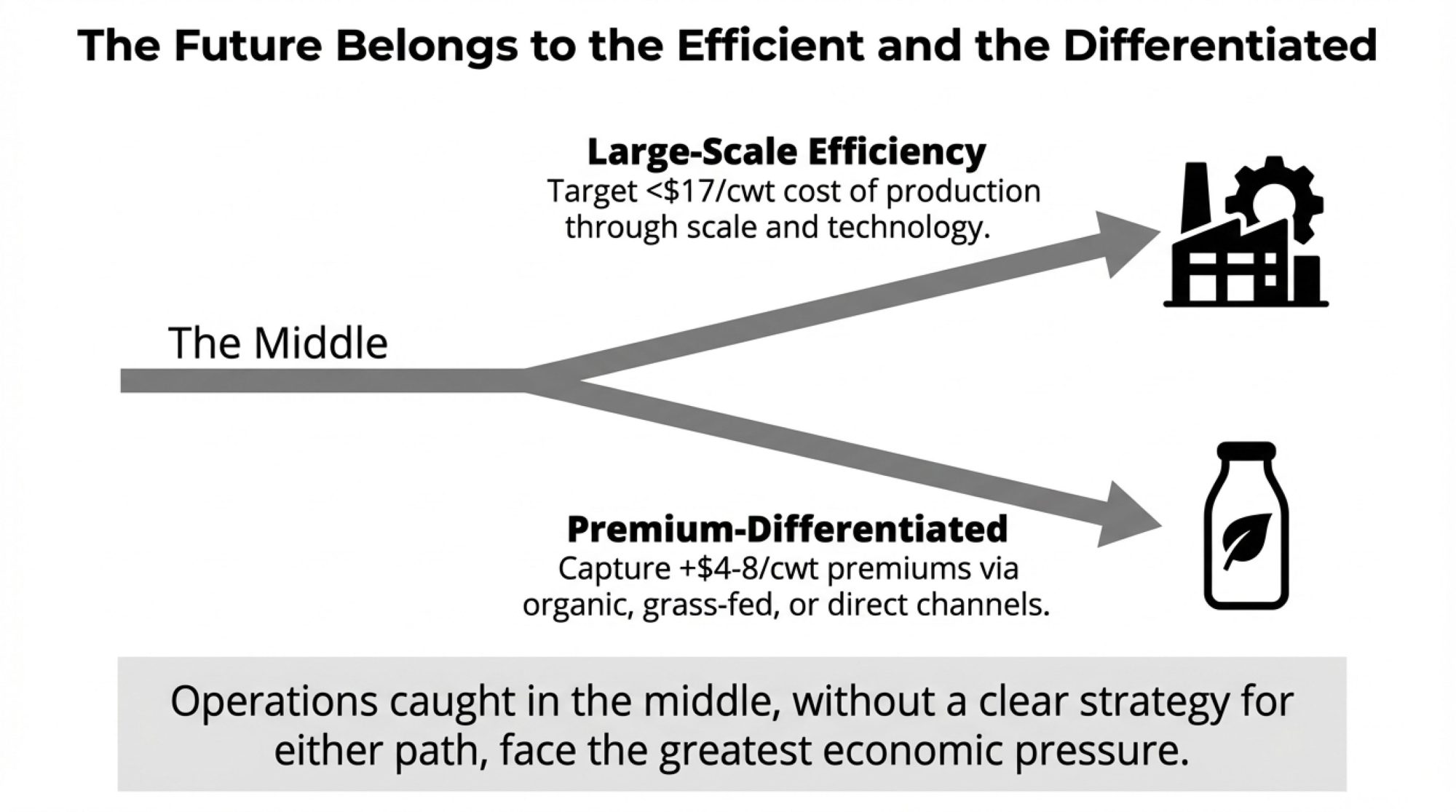

Strategic Levers by Scale

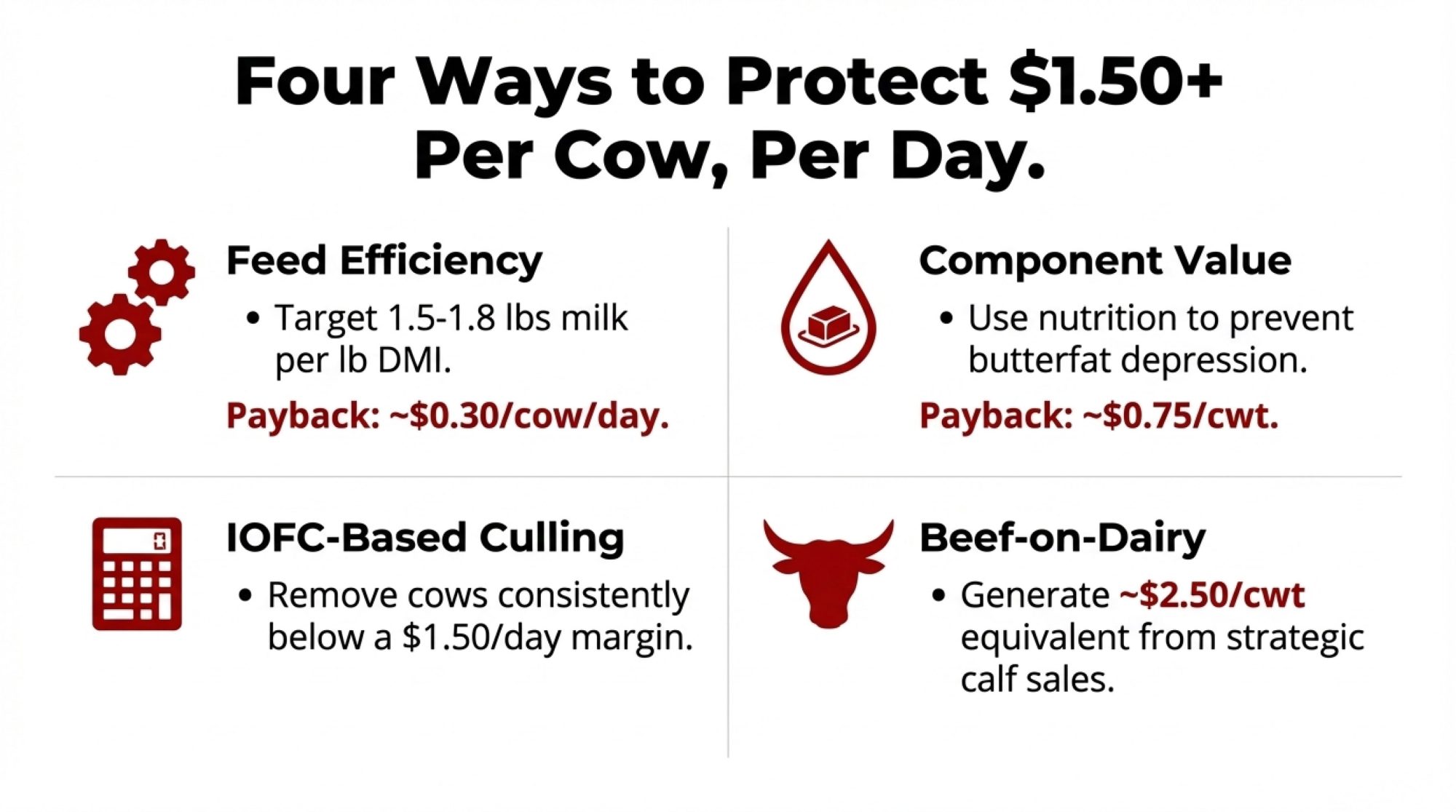

Even in challenging margin environments, individual operations retain meaningful levers. They won’t shift global prices, but they determine which side of the margin line you occupy.

Feed Efficiency and IOFC

Research consistently documents substantial variation in feed efficiency—both between herds and within individual herds.

Progress typically comes from:

- Forage quality management—harvest timing, processing, storage, feedout

- Fresh cow protocols that establish strong intake patterns during those critical first 30-60 days

- Active use of income over feed cost metrics as management tools, not retrospective reports

Getting started: On smaller operations, work with a nutritionist to develop simple IOFC reporting by production group. On larger TMR operations, establish monthly review rhythms to identify underperforming groups.

Component Value Capture

As payment systems emphasise solids over volume, butterfat and protein percentages deserve strategic attention.

The value ranges from 75 cents to $1.25 per hundredweight in many component-based systems, even at equivalent volume.

Getting started: Talk with your AI representative about reorienting sire selection toward fat and protein kilograms. Pair that with a nutritionist input on optimising rumen health, not just energy delivery.

Beef-on-Dairy Integration

This has evolved from a niche strategy to standard practice.

Getting started: Begin with market research. Talk with calf buyers about which terminal breeds and calving ease profiles actually command premiums in your area.

Financial Structure

What research keeps showing—across EU and Latin American farms alike—is that how you structure debt often matters as much as how efficiently you produce.

Getting started: Have proactive lender conversations before cash flow challenges emerge. Walk through three-year projections under multiple price scenarios.

The Takeaway: You can’t control global milk prices. But you can control feed efficiency, component focus, revenue diversity, and debt structure.

| Strategy | Immediate Impact | 1-Year Margin Gain | Resilience | Capital Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feed Efficiency Focus | Moderate — Slow gains | +$0.10-0.20/kgMS | High — Permanent | Low — Nutrition/management |

| Component Optimization | Moderate — Genetic lag | +$0.15-0.25/kgMS | High — Permanent | Low — Semen/consulting |

| Beef-on-Dairy Integration | High — Instant revenue | +$0.08-0.15/kgMS | Medium — Market dependent | Low — Contract only |

| Aggressive Debt Reduction | Low — Reduces cashflow | $0/kgMS | Very High — Future flexibility | High — Requires surplus |

| Volume Push (Status Quo) | High — Spreads fixed costs | -$0.05 to +$0.05/kgMS | Low — Worsens oversupply | Moderate — Feed purchases |

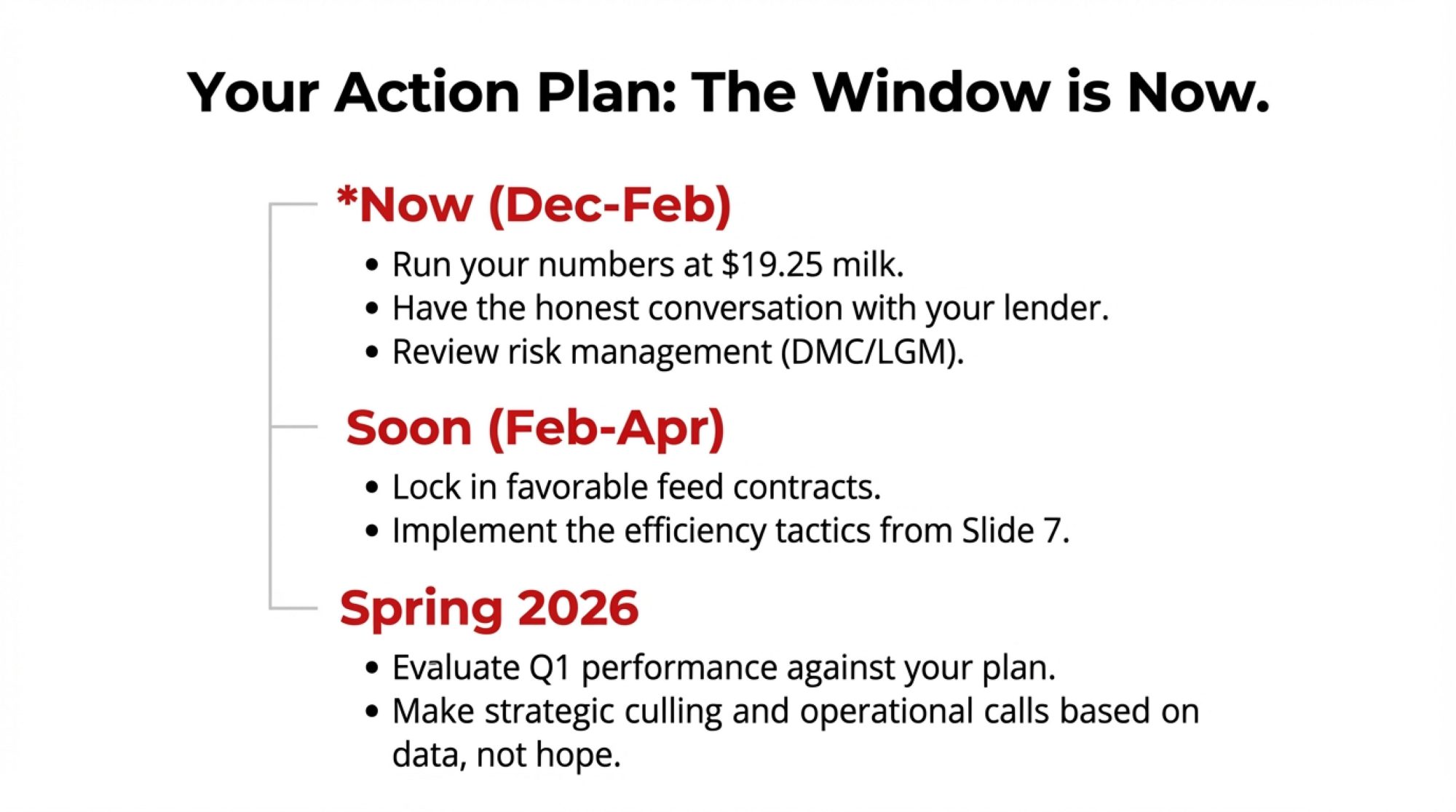

What Could Actually Change Things?

If current margin pressure is structural, what developments might shift the trajectory?

Genuine supply contraction would require sustained exits that actually reduce production capacity. We’re seeing accelerating consolidation in parts of Europe, the UK, and Australia. It’s unclear whether the pace is sufficient.

Emerging market demand growth offers longer-term potential in Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America. But developing those markets takes time.

Policy and structural changes—such as transition support, improved risk-sharing between processors and producers, and trade agreements—could shift the environment. But political processes move slowly.

None of these are quick fixes. But understanding the possibilities helps inform longer-term positioning decisions.

Key Takeaways

Price levels don’t ensure margin. A $9.50 per kgMS payout with $8.50 break-evens means strong prices can coexist with tight margins.

Volume gains require margin verification. More production can support cashflow while contributing to oversupply. Check IOFC, not just output.

Input decisions carry strategic weight. Feed and fertiliser now warrant careful analysis, not routine repetition.

Revenue diversification has moved mainstream. Beef-on-dairy and sustainability premiums are standard elements, not experiments.

Financial structure shapes survival. Operations that reduced debt during good years enter this period with more flexibility.

Opportunity persists, but looks different. More competition, more selective buying, more scrutiny. Adapt or get squeezed.

The Bottom Line

No individual farm can resolve global oversupply. No policy will quickly restore previous comfort levels.

But careful attention to what New Zealand’s numbers reveal—and thoughtful application regardless of region or scale—can improve the odds of staying on the right side of that one-dollar margin line.

The farms that thrive in 2030 are making decisions right now. Not necessarily to get bigger. But to get more resilient, more diversified, more intentional about where margin actually comes from.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Beyond the Milk Check: How Dairy Operations Are Building $300,000 in New Revenue Today – Reveals immediate financial strategies for 2025, detailing how silage management, targeted DMC coverage, and efficiency protocols can generate six-figure returns when milk prices alone fall short of break-even costs.

- The Wall of Milk: Making Sense of 2025’s Global Dairy Crunch – Provides a deep dive into the “24-month trap” of global oversupply, explaining why export records aren’t saving prices and how to position your operation against the structural shift in Chinese demand.

- Dairy Wins, Beef Loses: Inside the 18-Month Window Where $1,400 Calves Meet Record Component Premiums – Demonstrates how to capture the current $1,400 beef-on-dairy premiums while simultaneously breeding for the high-component milk that processors are demanding, effectively decoupling your revenue from liquid volume volatility.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!