When processor profits climb while your milk check drops, it’s not a coincidence. It’s a message. And once you understand what that message is telling you about how the modern dairy supply chain works, you can stop second-guessing yourself and start making strategic decisions.

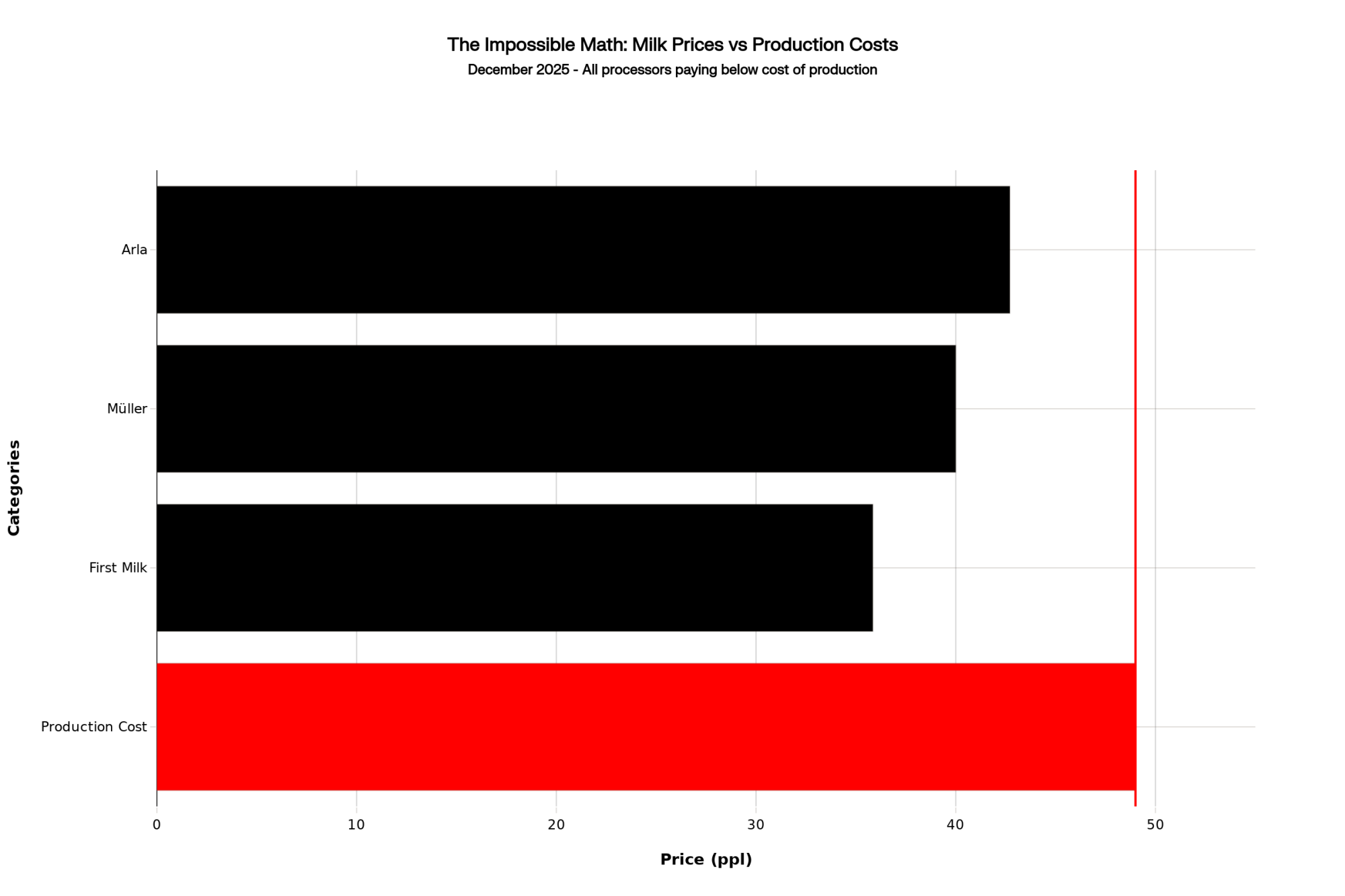

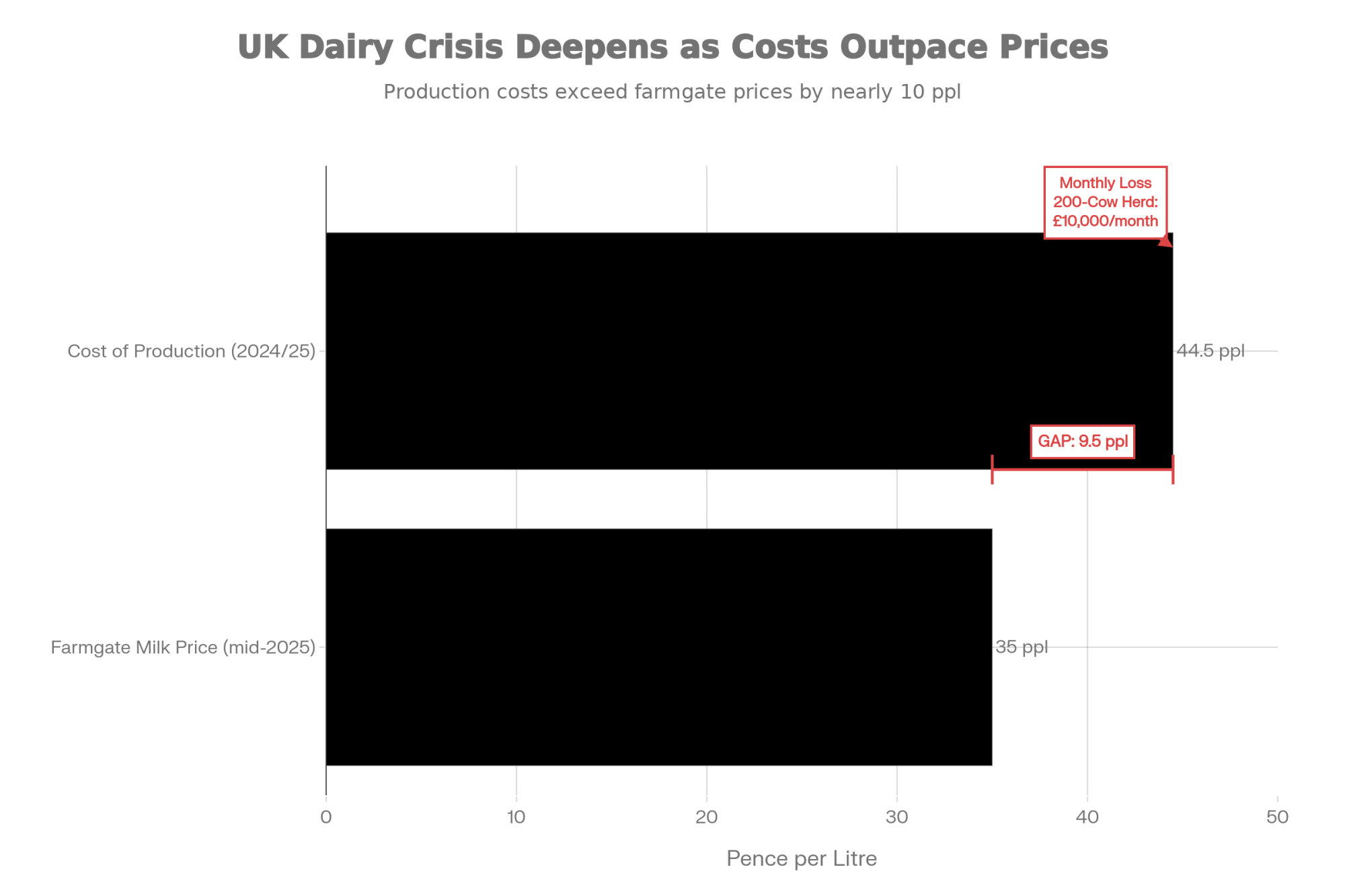

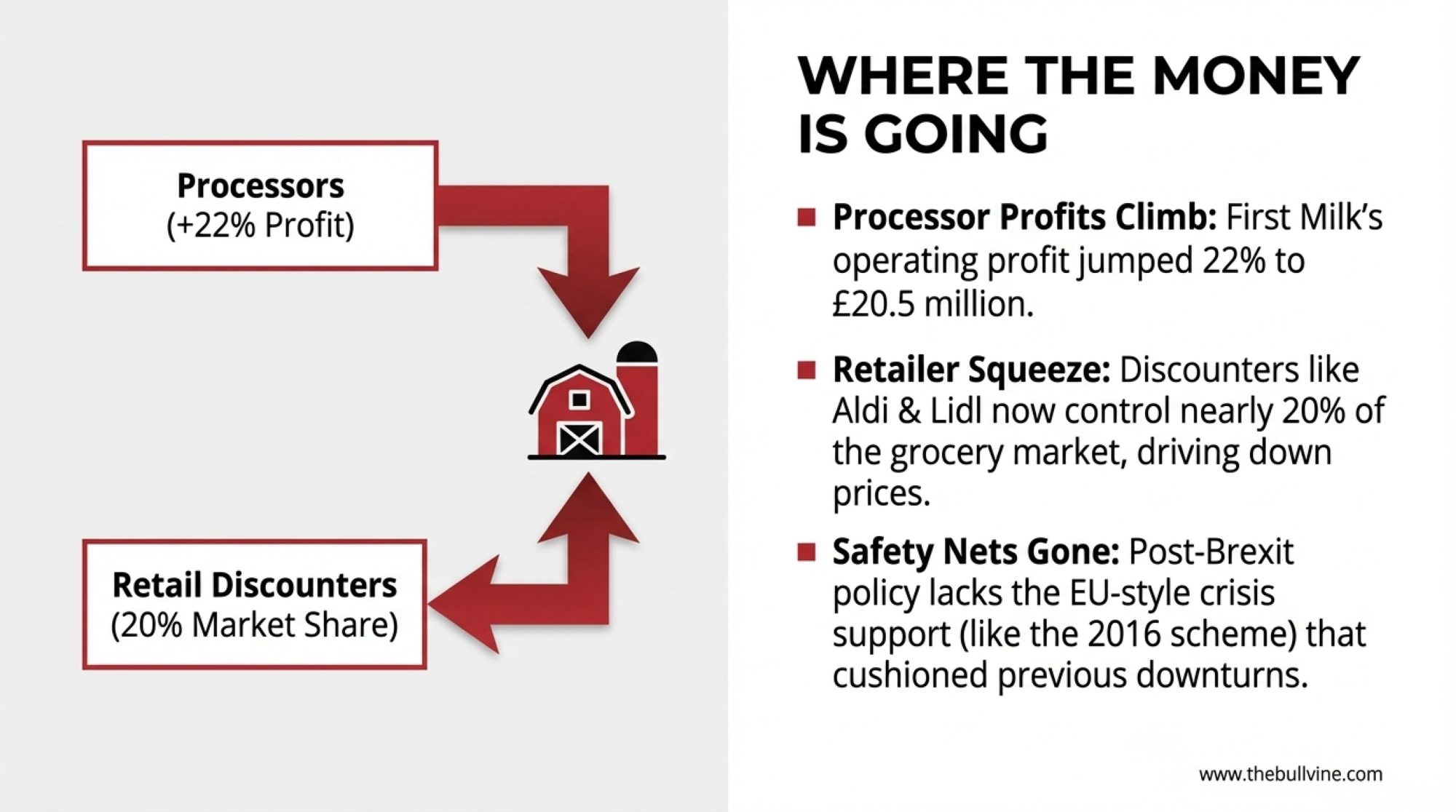

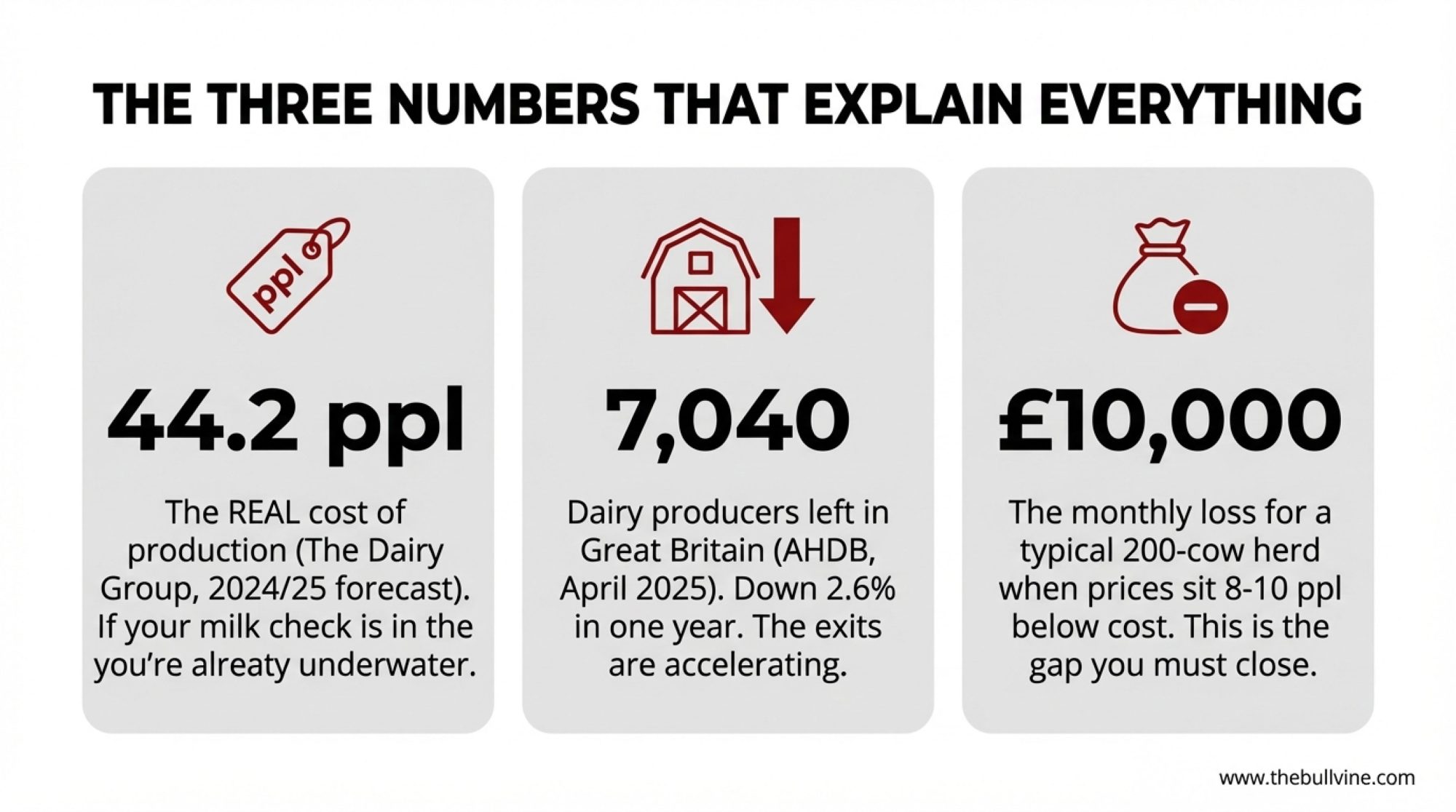

Executive Summary: A 200-cow UK dairy loses roughly £10,000 every month when milk price sits 8-10ppl below cost of production. Right now, that describes most operations. AHDB’s April 2025 data shows just 7,040 producers remaining in Great Britain—down 2.6% in a single year—while First Milk’s operating profit climbed 22% to £20.5 million. Retail discounters now command nearly 20% of UK grocery spend, and post-Brexit policy lacks the milk-specific safety nets that cushioned the 2015-2016 crisis. This isn’t farm failure. It’s market structure. Three approaches are delivering real results for producers fighting to stay viable: strategic culling of the bottom 15% of the herd, precision feed management with qualified nutritionist support, and capturing beef-cross calf premiums through targeted breeding. Combined, these strategies can reduce monthly losses by £7,000-8,000—buying time to explore processor alternatives and the collective engagement approaches already producing results in Ireland.

I’ve been talking with UK dairy farmers a lot lately, and you know what keeps coming up? This quiet worry that maybe they’re just not good enough at this anymore. That somehow the losses they’re seeing reflect something they’re doing wrong.

Here’s what I want to say to that: if you’re running a technically sound operation—decent yields, reasonable cell counts, professional management—and you’re still hemorrhaging money, that’s not farm failure. That’s market structure. And there’s a real difference between those two things.

Let me walk you through what I’m seeing.

The Numbers Behind the Frustration

So let’s start with the processor side, because that’s where this story begins.

First Milk’s Annual Financial and Impact Report for the year ending March 2025 shows turnover of roughly £570 million and operating profit around £20.5 million—up from £16.8 million the previous year. That works out to an operating margin just over 3.5%. The cooperative points to higher product volumes and the full integration of BV Dairy as key drivers.

Metric | 2023/24 | 2024/25 | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Milk Operating Profit | £16.8 million | £20.5 million | +22% ↑ |

| First Milk Operating Margin | ~3.2% | ~3.6% | +0.4pp ↑ |

| GB Dairy Producers | ~7,240 | 7,040 | -2.6% ↓ |

| Farms Exited | n/a | ~200 | -200 farms ↓ |

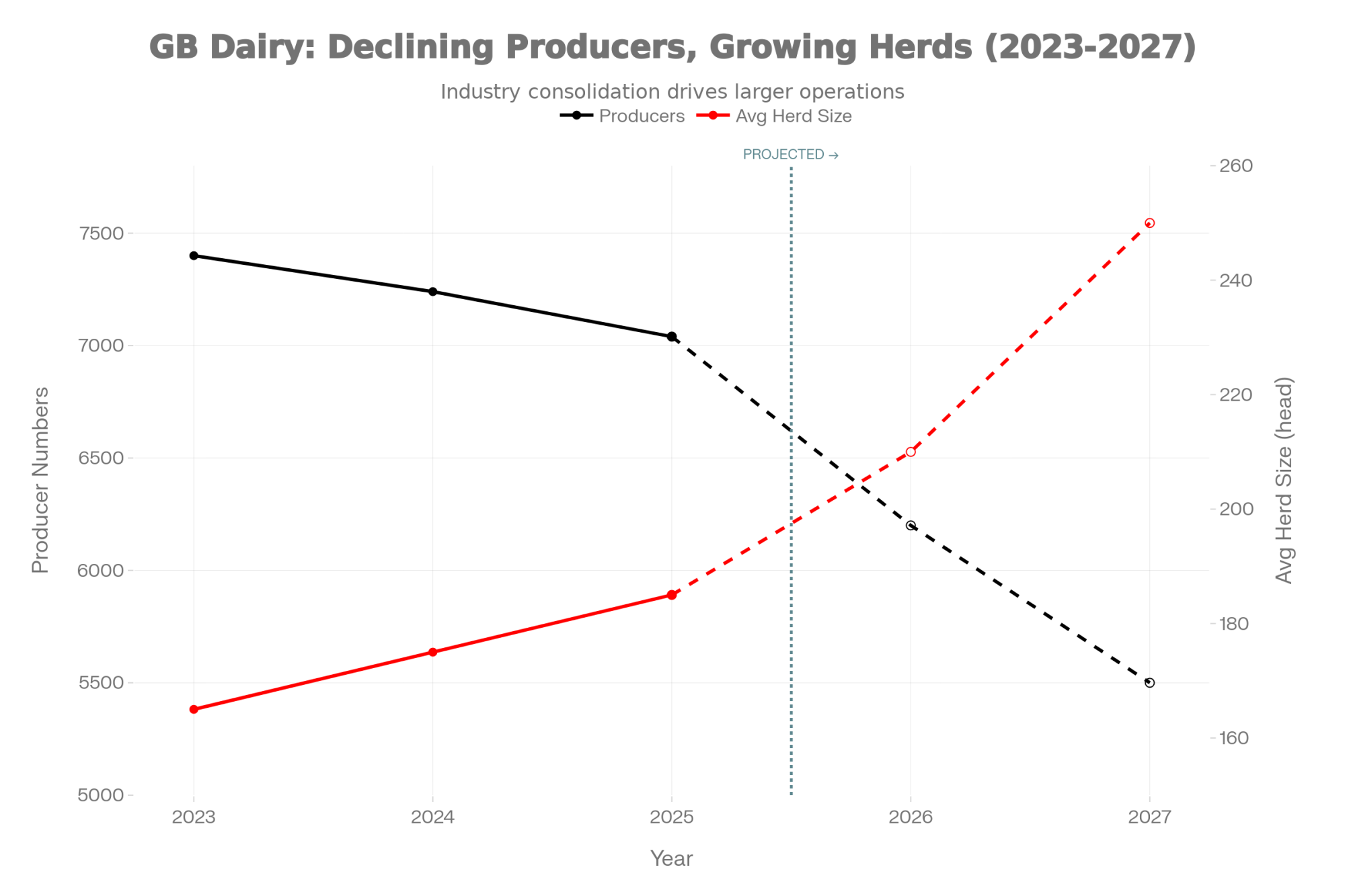

Meanwhile, AHDB’s producer numbers survey from April 2025 shows we’re down to about 7,040 dairy producers in Great Britain. That’s around 160 fewer than the previous survey in October, and nearly 200 fewer than a year ago—a 2.6% annual decline. The exits tend to cluster ahead of winter housing, which makes sense when you think about the capital and workload involved in bringing cows inside.

Here’s what’s interesting, though. Even as farm numbers drop, total milk production keeps climbing. AHDB data shows the GB milking herd continuing its gradual decline, but litres per farm keep rising. Fewer farms, bigger herds, more milk per unit. That pattern’s been consistent for decades now.

And the cost picture? The Dairy Group’s September 2024 newsletter pegs the UK cost of production for 2023/24 at around 45 ppl, with their forecast for 2024/25 at approximately 44.2 ppl. Their analysis suggests it’s “extremely unlikely” we’ll see costs drop back below 40 ppl anytime soon.

So when farmgate prices sit in the mid-30s and the cost of production hovers in the mid-40s, you’ve got a gap of roughly 8-10 ppl. For a 200-cow herd producing about 1.5 million litres annually, that works out to something like £120,000 a year—close to £10,000 a month just to stand still.

Now, every farm pencils out differently. But consultants I’ve spoken with say these kinds of numbers line up pretty closely with what they’re seeing in real accounts.

Why This Cycle Feels Different

If you’ve been farming through previous downturns, you’re probably thinking about 2015-2016 right now. Similar oversupply pressures, similar price corrections. But something feels different this time, and I think that instinct is worth exploring.

During the 2015-2016 crisis, Brussels stepped in with a €150 million EU-wide scheme—created through Delegated Regulation 2016/1612—that paid farmers voluntarily to reduce milk deliveries for a few months. According to the European Court of Auditors’ special report on the EU’s response to the milk market disturbances, aid was set at €14 per 100 kg of milk to reduce deliveries by around 1.1 million tonnes. It wasn’t a perfect solution, but it was something.

Since leaving the EU, the UK hasn’t had a like-for-like replacement for that specific tool. Support has tended to come through broader environmental schemes and general farm payments rather than milk-specific production incentives. When processors announce cuts today, there’s less cushion. And it’s worth noting that devolved agricultural policies mean Scottish and Welsh producers face different support landscapes than those in England—something that adds another layer of complexity when comparing notes with neighbours across borders.

The retail landscape has shifted, too. Kantar’s December 2025 grocery data shows Aldi holding about 10.5% of the UK market and Lidl at 8.1%. Together, discounters now account for close to a fifth of all grocery sales—up from around 13.6% just five years ago. That buying power inevitably influences how hard they push wholesale prices, including dairy prices. It’s not that traditional supermarkets don’t care about farmgate sustainability—many genuinely do—but it’s harder to hold that line when your competitors are focused purely on cost.

And then there’s the processor balance sheet question. First Milk and others have taken on debt for capacity investments and acquisitions. When leverage ratios are around 3x and debt service coverage needs to be protected, there’s real pressure to maintain margins. I don’t think farmers should dismiss these constraints as excuses—they’re genuine business realities that boards have to navigate.

What producers are discovering is that the support architecture from the last major crisis has changed. Understanding that helps you think more clearly about your options.

Three Approaches That Are Actually Working

Understanding the market is useful, but you need actionable steps. I’ve been tracking what’s delivering results for farms navigating this environment, and three approaches keep coming up in the operations that are extending their runway.

Taking a Hard Look at the Herd

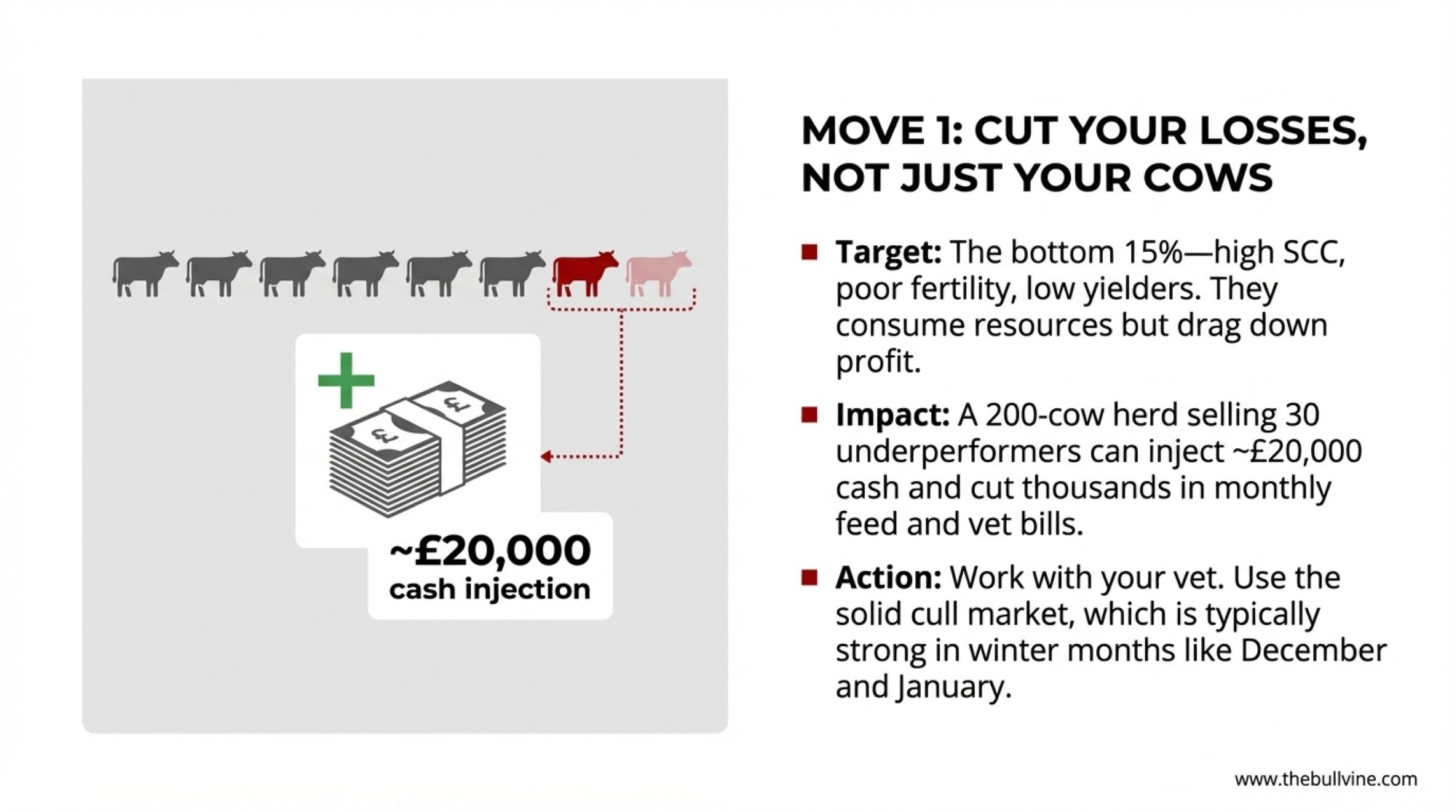

Here’s something that sounds counterintuitive but makes good financial sense: thoughtful culling can improve your monthly position even while reducing production.

You probably know this already, but the bottom 15% of most herds—cows with persistent cell counts above 400,000, yields consistently below 20 litres daily, or chronic fertility challenges—consume similar feed, labour, and veterinary resources as top performers while generating less revenue meaningfully. We’ve understood this principle for years, but current market conditions make acting on it more urgent.

I recently spoke with a consultant who walked through the numbers with a 200-cow client in northern England. They identified about 30 chronically under-performing cows—high cell counts, repeated fertility issues, cows that had been given plenty of chances—and sold them into a solid cull market at roughly £650 a head. That brought in close to £20,000 in cash.

| Financial Component | Calculation (200-cow herd) | Impact |

| Bottom 15% Identified | 30 chronically under-performing cows | High SCC, low yield, poor fertility |

| Immediate Cull Revenue | 30 cows × £650/head | £19,500 cash |

| Monthly Feed Savings | Reduced ration costs + supplements | £2,000-3,000/month |

| Annual Feed Savings | £2,500/month × 12 months | £24,000-36,000/year |

| Total Year 1 Financial Impact | Cash + savings | £43,500-55,500 |

Source: Consultant case study, northern England; cull market pricing autumn 2025

More importantly, the farm cut its monthly feed bill by several thousand pounds and saw modest savings in vet and labour costs. The net effect moved them from a deeply negative monthly position to a more manageable one.

While every herd pencils out differently depending on your system, your cull market, and your costs, these are the kinds of numbers many accountants are now working through with clients. The key is being honest about which animals are genuinely contributing and which are just consuming resources. Work with your vet to ensure culling decisions account for your calving pattern and transition cow management—you don’t want to create gaps in your fresh cow pipeline that cause problems six months down the road.

With December and January typically being strong months for cull cow demand—processors need to fill orders before spring, and the beef trade tends to hold up well through winter—the timing for these decisions is actually reasonable right now.

Getting Smarter on Feed

Feed typically represents 40-60% of production costs, so even modest improvements here compound meaningfully. Two levers deserve attention, and they work well together.

The first involves precision nutrition. Advisers from groups like The Dairy Group and Kingshay regularly highlight the gap between typical and efficient operations on concentrate use—sometimes 0.50 kg per litre versus 0.41 kg per litre. That gap represents real money over the course of a lactation.

But here’s the thing—and I can’t stress this enough—closing that gap requires proper involvement from a nutritionist. Cut too aggressively without professional guidance, and you risk losing more in butterfat and protein performance than you save on inputs. I’ve seen farms try to do this on their own and end up worse off because yields or components drop. Get someone qualified involved before you change rations.

The second lever is collective purchasing. Advisers from Kingshay and The Dairy Group report that members of their buying groups can often secure noticeably better prices on straights and blends than lone buyers—sometimes shaving several pounds per tonne off the ticket price. The exact savings vary by region and by what you’re buying, but across a winter, those differences add up.

What’s encouraging is that I’m hearing about more farms in the Southwest and Midlands joining these groups this autumn. The administrative overhead is minimal, and the buying power is real.

Finding Revenue on the Margins

This is where farms can add income without major capital requirements.

In current UK auctions, it’s not unusual to see well-bred beef-cross dairy calves selling for several times the value of plain dairy bull calves. One recent market report from the South of England showed continental-cross calves comfortably into the low hundreds of pounds, while plain dairy bulls lingered at much lower values. Using sexed beef semen on cows not needed for herd replacement is a straightforward way to capture some of that premium.

| Calf Type | Typical Market Value | Annual Calves (200-cow herd) | Annual Revenue | Premium vs Dairy Bull |

| Plain Dairy Bull | £20-40 | 50 | £1,000-2,000 | Baseline |

| Beef-Cross (Continental) | £100-150 | 50 | £5,000-7,500 | +£4,000-5,500 |

| Your Opportunity | Switch 40-50 calves | 40-50 | +£3,200-6,000 | £80-120 per calf |

For a 200-cow operation with flexibility on breeding decisions for 100-plus females, targeting 40-50 beef crosses annually can add meaningful revenue without changing much else about your system.

The contracting opportunity also deserves a look. The NAAC Contracting Prices Survey for 2024-25 puts typical charges for slurry spreading with a tanker and trailing shoe at around £75 per hour, with forage harvesting operations ranging from £83 to over £200 per acre depending on the service level. For a farm with decent machinery and some spare labour capacity, doing a modest amount of contract work for neighbours can turn idle time into a few hundred pounds a month during peak seasons.

Neither of these is transformative on its own. But combined with the herd and feed work, they add up to something that can make the difference between a sustainable position and a forced exit.

The Combined Picture

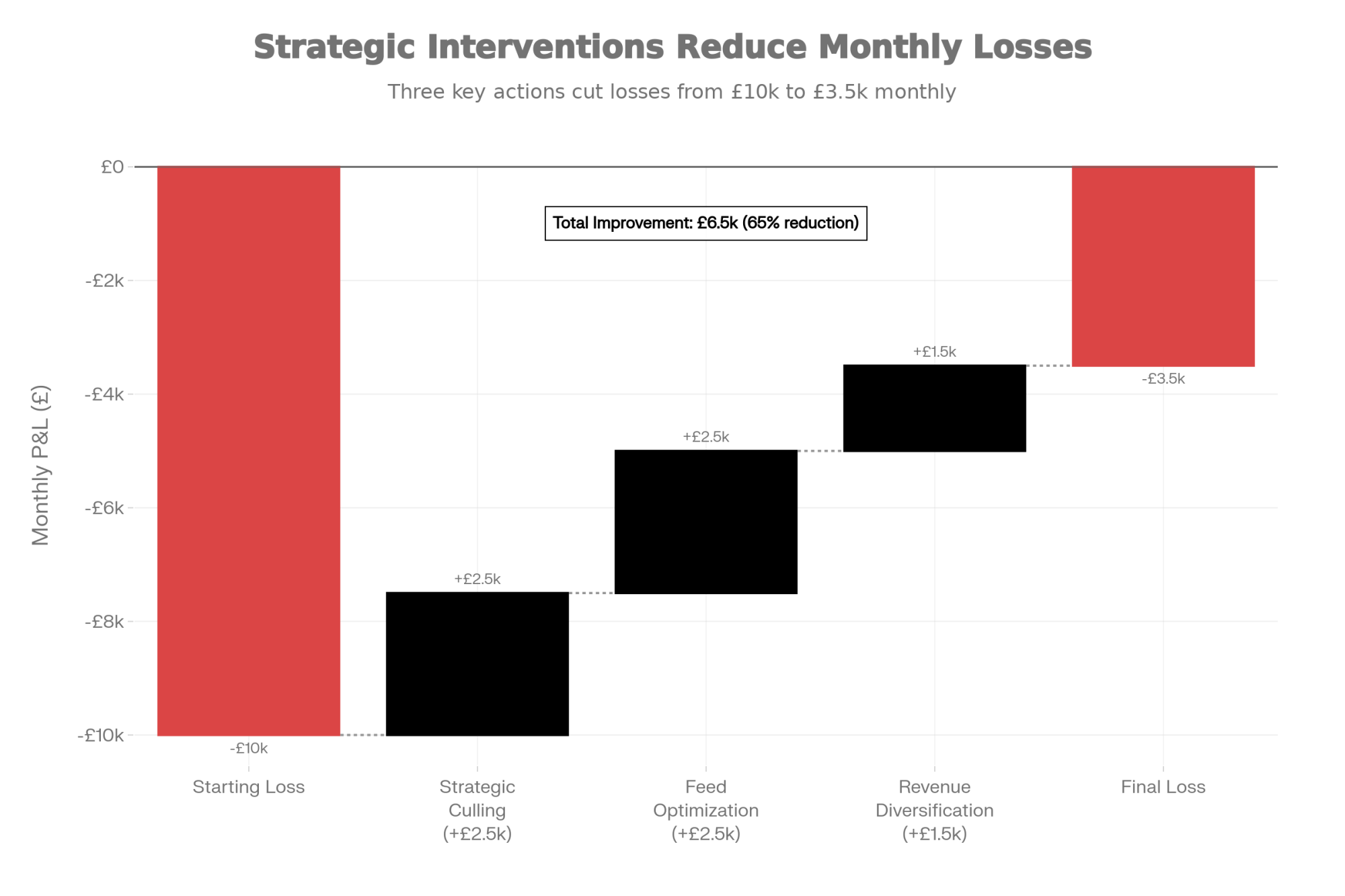

When I model all three approaches together—strategic culling, feed optimisation, and revenue diversification—the financial shift becomes meaningful.

For a 200-cow operation starting at roughly £10,000 monthly losses, you might get that down to £2,000-3,000 monthly through these changes, plus a one-time cash injection from the cull animals. For larger 500-cow operations, the numbers scale accordingly.

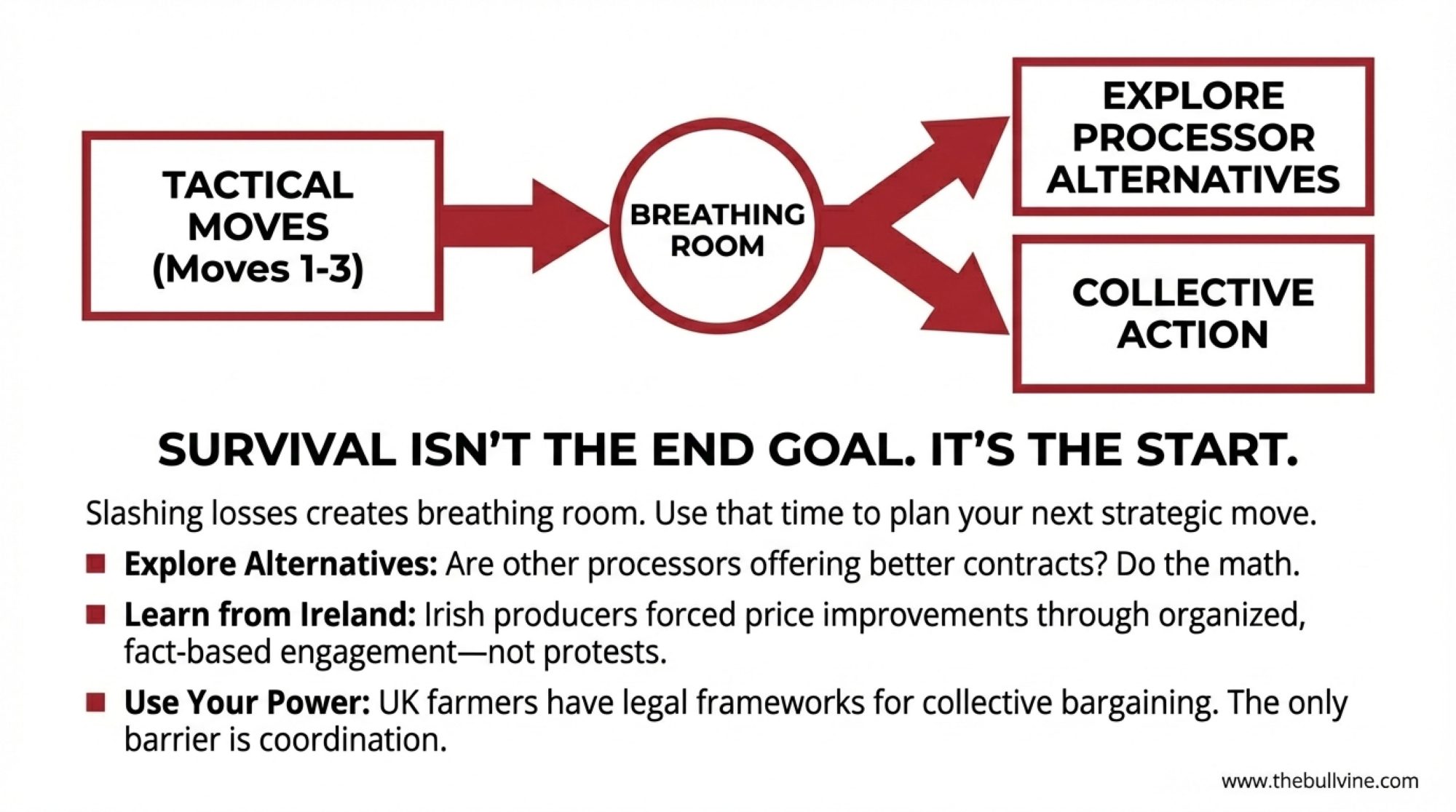

That’s not a permanent solution—farmgate prices are still below the full cost of production. But it creates time. Time to explore processor alternatives if better prices are available elsewhere. Time to think about collective approaches. Time to restructure financing if needed. Time to plan transitions thoughtfully rather than under immediate pressure.

And that time matters more than people often realise.

What the Irish Experience Suggests

I’ve been following developments at Dairygold in Ireland because they offer an interesting case study in producer coordination.

When Dairygold announced pricing adjustments this autumn, Irish farming media reported that several hundred farmers quickly organised around concerns about pricing and attended regional meetings with detailed written questions. While the exact figures vary depending on who you talk to, producers on the ground say this collective approach helped prompt partial improvements in the farmgate price rather than further cuts.

Their approach was notably constructive—no protests or supply withholding, just organised attendance at meetings with specific questions about pricing formulas, operational costs, and capital allocation. When a meaningful share of your supplier base shows up with identical written questions, it changes the tone of the conversation.

What’s worth noting is that UK farmers actually have stronger legal frameworks available to them. Recent Defra regulations mandate pricing transparency and good-faith engagement in dairy contracts, and producer organisation structures enable collective dialogue without competition law concerns.

The barrier isn’t legal authority—it’s coordination. And the Irish experience suggests coordination doesn’t require formal structures or membership dues. It requires communication channels, commitment mechanisms, and producers willing to engage constructively with specific questions.

Looking Ahead: What the Projections Suggest

If current pricing dynamics persist, what trajectory should producers anticipate?

Based on AHDB data and Andersons’ outlook analysis, the consolidation pattern we’ve seen for decades looks set to continue—possibly accelerate. According to the Andersons Outlook report covered by Dairy Global, authors Mike Houghton, Oliver Hall, and Tom Cratchley project that GB dairy producers could fall to between 5,000 and 6,000within the next two years. Average herd size would continue climbing, possibly toward 250 head or beyond. Total production would likely remain stable as surviving farms expand.

Exit rates will probably vary significantly by scale and region. Smaller operations—those under 100-150 cows—generally face steeper challenges because their cost structures tend to run higher. Larger operations often achieve better economies of scale on fixed costs. That’s not a judgment about who’s a better farmer; it’s just the economics of spreading overhead across more litres.

Understanding this trajectory helps you make informed decisions about your own operation and timeline.

A Word on Cooperatives

Under UK cooperative law, boards are expected to act in the long-term interests of the society and its members, which often means paying close attention to balance-sheet strength, covenants, and investment needs alongside the current milk price. In practice, management decisions sometimes lean toward protecting the co-op’s viability, even when members face short-term income pressure.

I want to be fair here—boards aren’t being malicious when they make difficult pricing decisions. They’re navigating genuine constraints and competing obligations. But fairness has limits.

Loyalty is a two-way street. If the governance structure consistently prioritizes the institution over the member’s survival, the member has to ask a hard question: Am I actually an owner here, or am I just a supplier with a liability attached?

Because there’s a difference between a cooperative that asks members to share sacrifice during difficult periods and one that protects its margins while members bleed equity. The first is partnership. The second is something else entirely.

Different cooperative models do exist internationally. Some Canadian and European structures have achieved farmgate prices meaningfully above UK equivalents through different charter provisions and member engagement approaches. Whether UK cooperatives could evolve similarly is an open question—but it won’t happen without sustained producer engagement in governance processes. Boards respond to pressure. If members don’t apply it, nothing changes.

The Bottom Line

If you’ve read this far, you’re probably thinking about what all this means for your own situation. Let me offer a few thoughts.

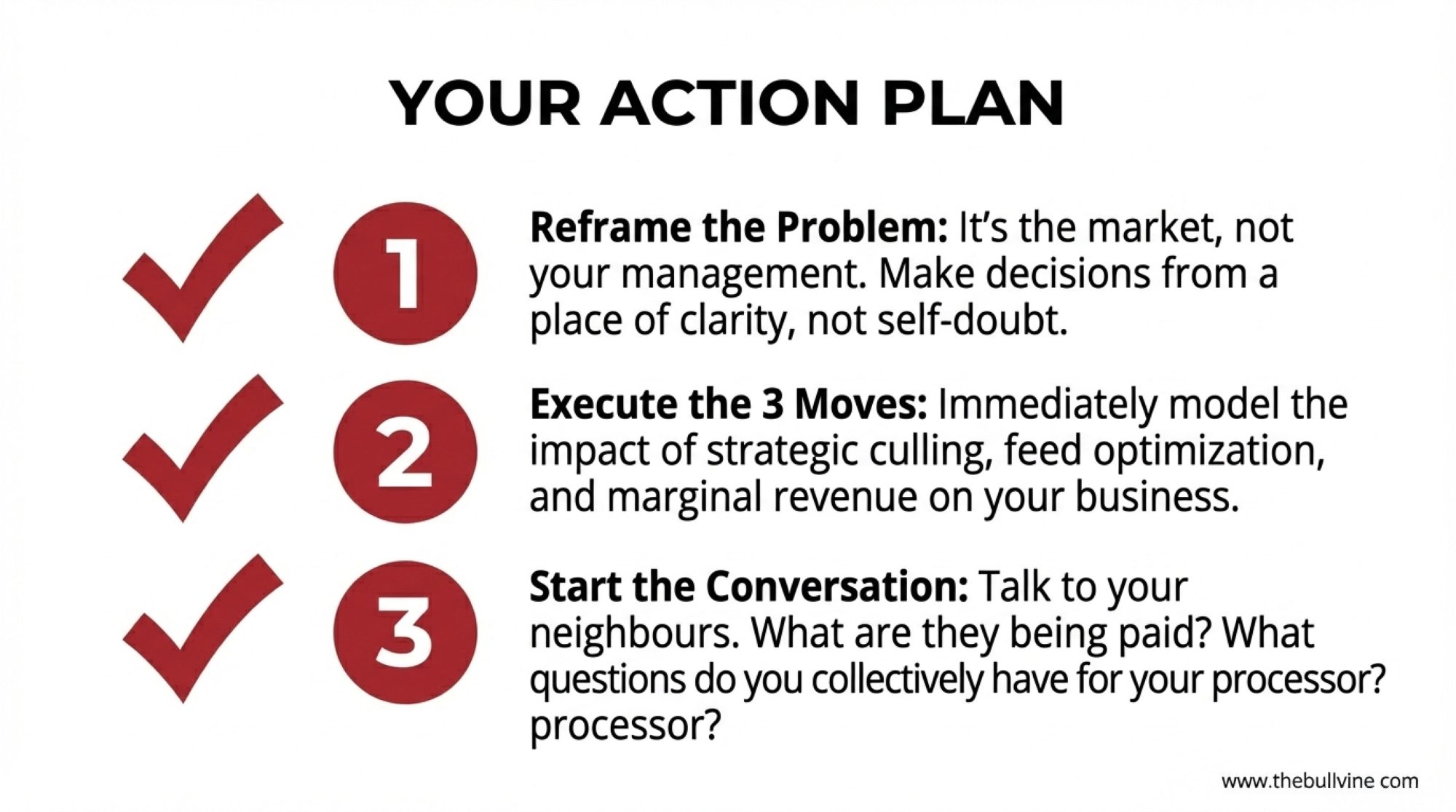

First, understand where your losses are actually coming from. If you’re losing money but your operational metrics—yield, cell count, fertility, labour efficiency—compare reasonably well to industry benchmarks, your challenge is primarily market structure rather than farm management. That distinction matters for how you respond.

Second, don’t wait to act on the things within your control. The herd optimisation, feed work, and revenue diversification I described aren’t heroic measures—they’re sound management practices worth pursuing regardless of market conditions. Many farms should already have been doing this work. Current conditions just make it more urgent.

Third, explore your options on processor relationships. If there are meaningful price differences between your current buyer and alternatives, those differences add up fast. A few pence per litre on a million-plus litres is real money. Understand your contract terms, your notice requirements, and what’s actually available in your area.

Fourth, consider whether collective engagement makes sense for you. The Irish example shows that coordinated, fact-based dialogue can influence how processors make decisions. You don’t need to start a movement—even talking with neighbours about what you’re seeing in your milk cheques and what questions you’d want answered can be valuable.

And finally—and this one matters—make your decisions from clear analysis rather than frustration or self-doubt. If your operation is technically sound and you’re still losing money, that’s important context. It means the problem isn’t fundamentally about you. It means there are structural market factors at work. And understanding that changes how you evaluate your options.

These are difficult times in the UK dairy industry. But difficult times also clarify what matters and what actions are worth taking. The farms that navigate this well won’t be the ones who hoped for markets to improve. They’ll be the ones who understood their situation clearly, acted on what they could control, and made thoughtful decisions about their future.

That’s within everyone’s reach.

Practical Resources

- AHDB Dairy: Benchmarking tools, market data, and cost of production analysis at ahdb.org.uk/dairy

- Kingshay: Dairy costings service and buying group information at kingshay.com

- The Dairy Group: Technical consultancy and feed analysis at thedairygroup.co.uk

- NAAC Contractor Rates: Current pricing guides at naac.co.uk

Key Takeaways

- The gap is £10,000/month. That’s what a 200-cow herd loses when milk sits 8-10ppl below cost. Most UK dairies are there now.

- It’s not your farming. Processor profits up 22%. Producer numbers down 2.6%. This is market structure—not management failure.

- Three moves that work. Cull the bottom 15%. Tighten feed with a nutritionist. Capture beef-cross premiums. Combined savings: £7,000-8,000/month.

- You’re buying time, not salvation. These strategies create breathing room—to switch processors, explore collective action, or plan transitions on your terms.

- Coordination changes everything. Irish producers shifted pricing through organised, fact-based engagement. UK farmers have stronger legal tools. They just need each other.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- FEED EFFICIENCY BOMBSHELL: Yeast Additives Expose the Truth About High-Starch Dairy Diets – Reveals how specific yeast supplementation can boost feed efficiency by 7.6% and improve conception rates by 50%, offering a scientifically proven nutritional lever to widen margins when feed costs are high.

- The Wall of Milk: Making Sense of 2025’s Global Dairy Crunch – Analyzes the “global supply collision” behind the current price drop, providing the macro-economic context you need to understand why this downturn differs from 2015 and how long the pressure might last.

- 2025 Dairy Year in Review: Ten Forces That Redefined Who’s Positioned to Thrive Through 2028 – WARNING: Before you cull heavily, read this analysis of the severe 27-month heifer shortage and new component pricing standards that are permanently reshaping replacement costs and milk value.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.