How a farm boy’s love of pedigrees sparked a data revolution that reshaped global dairy genetics—and why his lessons matter more than ever in 2025

The young bull arrived at the Centre d’Insémination Artificielle du Québec in the fall of 1967 with papers that would make any geneticist’s heart race. Three generations of sires with AI proven positive indices in both production and conformation—an almost unheard-of alignment of genetic excellence. On paper, this calf was exactly what the testing program needed.

But here’s where it gets interesting. His dam’s photo? Disappointing. Lacked the dairy character breeders prized. And worse—much worse, actually—she wore a speckled coat pattern that most cattlemen viewed with something between annoyance and outright dread.

Now, you have to understand something about 1967. Breeders had to hand-draw the coat markings of every calf submitted for registration. Every. Single. One. The prospect of reproducing that mottled pattern on form after form, getting all those spots just right… it was enough to make most turn away without a second glance.

When 73HO101 Senator—as he’d come to be known—was offered for testing, the Quebec breeding community responded with collective indifference. Most ignored him outright. CIAQ’s inseminators eventually got instructions to use his semen when a farmer requested a test bull without naming a specific choice. A last resort for an animal nobody wanted.

What happened next would validate a philosophy that had been building for years in the mind of one young geneticist. It would prove that the future of dairy breeding lay not in what the eye could see, but in what the numbers revealed. And it would cement Robert Chicoine’s legacy as one of the most consequential figures in the history of Canadian animal genetics.

The same principle that vindicated Senator now powers the SNP chips ranking your next breeding decisions. That’s not a coincidence—that’s legacy.

The Gift of The Holstein-Friesian Journal

Long before he’d revolutionize an industry, Robert Chicoine was a boy captivated by cows on a modest mixed farm in Saint-Pie-de-Bagot, Quebec. Born in 1943, he grew up surrounded by the familiar rhythms of rural life—laying hens clucking in their coop, apple trees bearing fruit in the small orchard, maple sap running each spring for the family’s syrup. The farm’s 15 to 20 dairy cows provided the primary source of income, with their milk destined for a Montreal dairy that paid nearly double the local rate in exchange for strict hygiene protocols and consistent year-round volume.

But it was the cattle that held young Robert’s complete attention. You know how some kids gravitate toward tractors, others toward the fields? Chicoine was a barn kid through and through. Whenever his family visited relatives or friends who farmed, he had only one request: to see the herd.

People noticed. An uncle who belonged to the Holstein Association of Canada recognized something in his nephew’s eyes—that spark you see in young people who just get it when it comes to cattle. Each month, after glancing through his copy of The Holstein-Friesian Journal, he’d pass it along to the boy who waited with barely contained anticipation.

“For me, this was the most beautiful gift I could receive,” Chicoine later recalled.

He spent hours poring over those pages, memorizing the names of advertised animals and studying their performance data—individual lactations, lifetime production, fat percentages—until the information became second nature. The kind of obsessive studying that would make any modern breeder recognize a kindred spirit.

His parents, watching their son’s devotion deepen with each passing season, made him a proposition that would alter the course of his life. If he agreed to handle all the paperwork and draw the animal portraits for registration applications, they’d gradually transition their grade herd to purebred Holsteins. It was a moment of trust and responsibility—the kind that plants seeds for everything that comes after.

Around the same time, the family kept a small flock of Bantam chickens in varied colors to brighten the farmyard. What began as decoration became Robert’s first laboratory. His parents let him build a separate flock where he could control which males bred with which hens, carefully observing how traits like color passed from one generation to the next.

“My little experiments with the Bantam chickens demonstrated to me with certainty that a breeding male can influence an entire herd,” he explained, “and even a whole segment of a population with the use of artificial insemination.”

Those childhood experiences—the journals filled with performance data, the hands-on breeding experiments, the patient parents who recognized and nurtured his interests—formed the bedrock upon which everything else would be built.

A Conversion in the Lecture Hall

When Robert Chicoine arrived at Laval University in the fall of 1960, Quebec itself was transforming. The ultra-conservative Duplessis era had ended, replaced by Jean Lesage’s Liberal government and its promise to modernize the province. It was the dawn of the Quiet Revolution—a period that championed science and gave education new prominence. In agriculture, the mandate was clear: productivity must improve, and quickly.

Chicoine came to university already fascinated by the performances of high-producing cows—those exceptional animals whose records qualified them for the honor roll published annually in the Holstein Journal. But his genetics courses delivered a revelation that would become the intellectual foundation of his entire career.

Here’s the thing about phenotype and genotype that changed everything for him: what you can observe—the physical expression of an animal’s traits—is only part of the equation. Environment and management play enormous roles in shaping a cow’s performance.

Think about it this way. A bull whose daughters averaged 8,000 kg of milk wasn’t necessarily superior to one whose daughters averaged 7,500 kg—not if the first bull’s daughters happened to be in high-feeding, top-management herds while the second bull’s daughters labored under average conditions. The raw numbers, stripped of context, could deceive. We’re still wrestling with this same issue today when we compare herds running robots versus parlors, or operations in Wisconsin versus Arizona.

This insight led Chicoine to embrace a method called Contemporary Comparison. Rather than judging a bull solely by his daughters’ raw production totals, this approach compared those daughters against the daughters of other bulls of the same age, in the same herds, during the same season. It created a level playing field that isolated the genetic contribution from the noise of management and environment.

It was a conversion—from intuition to analysis, from impressions to evidence, from what his grandfather’s generation believed to what the science actually showed. And it would become the philosophy he carried into battle against decades of ingrained industry skepticism.

The Challenge Nobody Warned Him About

A summer job at CIAQ in 1963 proved to be the pivot point. Management noticed the young man’s knowledge and passion for the Holstein breed, and before his internship ended, they extended an extraordinary offer: return after completing a Master’s degree in animal breeding, and take on the task of establishing Quebec’s first young sire testing program.

Chicoine was thrilled. His Master’s research, conducted under Dr. C.G. “Charlie” Hickman at the Ottawa Experimental Farm, taught him the mechanics of managing a testing program. But it also revealed critical flaws in the research project he was observing—it ignored conformation indices, causing the physical type of the herds to regress, and it used a closed population that limited genetic diversity.

From these lessons, he extracted a principle that would guide his entire approach: “To be acceptable to dairy producers, particularly those in purebred breeding, one must offer the testing program young bulls that have the best possible indices in production, but they must also have attractive indices in conformation.”

Sound familiar? We’re still having this exact conversation in 2025—balancing production traits against longevity, health traits, fertility, and feed efficiency. The fundamentals Chicoine identified sixty years ago haven’t changed.

On March 22, 1966, Robert Chicoine walked into CIAQ with a clear mandate—and an enormous problem.

For more than twenty years, animal production specialists had been preaching a single gospel to farmers: use herd proven bulls. Artificial insemination had given ordinary producers access to the very best genetics, and the message had been hammered home at every meeting, in every article, through every extension service. Now Chicoine had to convince those same farmers to do something that seemed to contradict everything they’d learned. He had to ask them to reserve a portion of their herds for young, unproven sires from his testing program.

“It was a great challenge,” he acknowledged—with what I suspect was considerable understatement.

Winning Hearts Through Data and Mail

Chicoine launched a campaign of patient persuasion that would span years. Picture him at those meetings—a young man not long out of university, standing in front of packed halls of weathered farmers in their good boots, the smell of coffee and cow still lingering on work clothes. Skeptical faces everywhere. These weren’t academics; these were men who’d been told for decades to trust proven bulls, and here comes this kid telling them to try something different.

He wrote article after article for industry publications, explaining the science of contemporary comparison in terms that farmers could understand. He spoke at annual meetings of insemination clubs and breed associations across the vast Quebec territory—sometimes so remote that travel required small aircraft.

A particularly effective collaboration emerged with Raymond Corriveau, a fellow Laval graduate who’d joined Holstein Canada as a regional representative. Corriveau’s information days were already popular with breeders, and he regularly invited Chicoine to present alongside speakers covering nutrition and management. During these sessions, Chicoine patiently explained principles that often sparked vigorous debate—like his assertion that a cow, regardless of her raw production totals, shouldn’t be considered a bull mother unless she was positive compared to her contemporaries.

“Which often created good discussions!” he recalled with characteristic understatement.

He promoted research from the University of Guelph demonstrating that optimal genetic gain could be achieved by using young test bulls on 40% of a herd’s females and proven sires on the remaining 60%. The study’s author, Murray Hunt, had since joined Holstein Canada’s staff in Brantford, lending credibility to the formula that Chicoine preached. (Read more: Dad at 80: How Murray Hunt Revolutionized Canadian Dairy Genetics)

But perhaps his most ingenious move was the mailbox campaign. From the beginning of the program, CIAQ made a habit of mailing the pedigrees and photographs of each new young bull to every breeder whose herd qualified for genetic evaluations. Part education, part marketing, wholly effective at building anticipation and loyalty.

“Over the years, several breeders confided in me that when they were young, they waited impatiently for the arrival by mail of the pedigrees of these young bulls,” Chicoine recalled. “Thus, a bond of loyalty to the program was created from one generation to the next.”

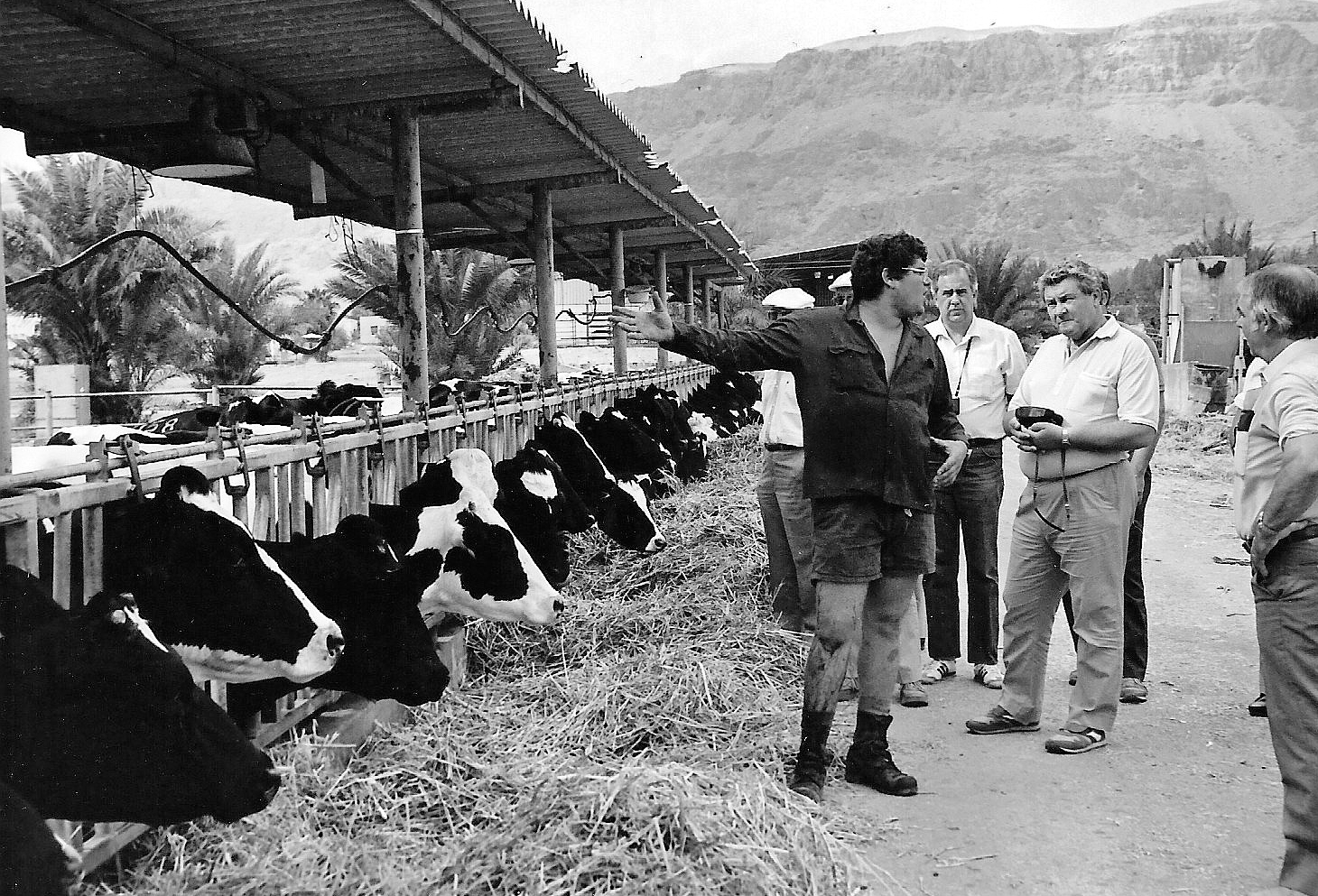

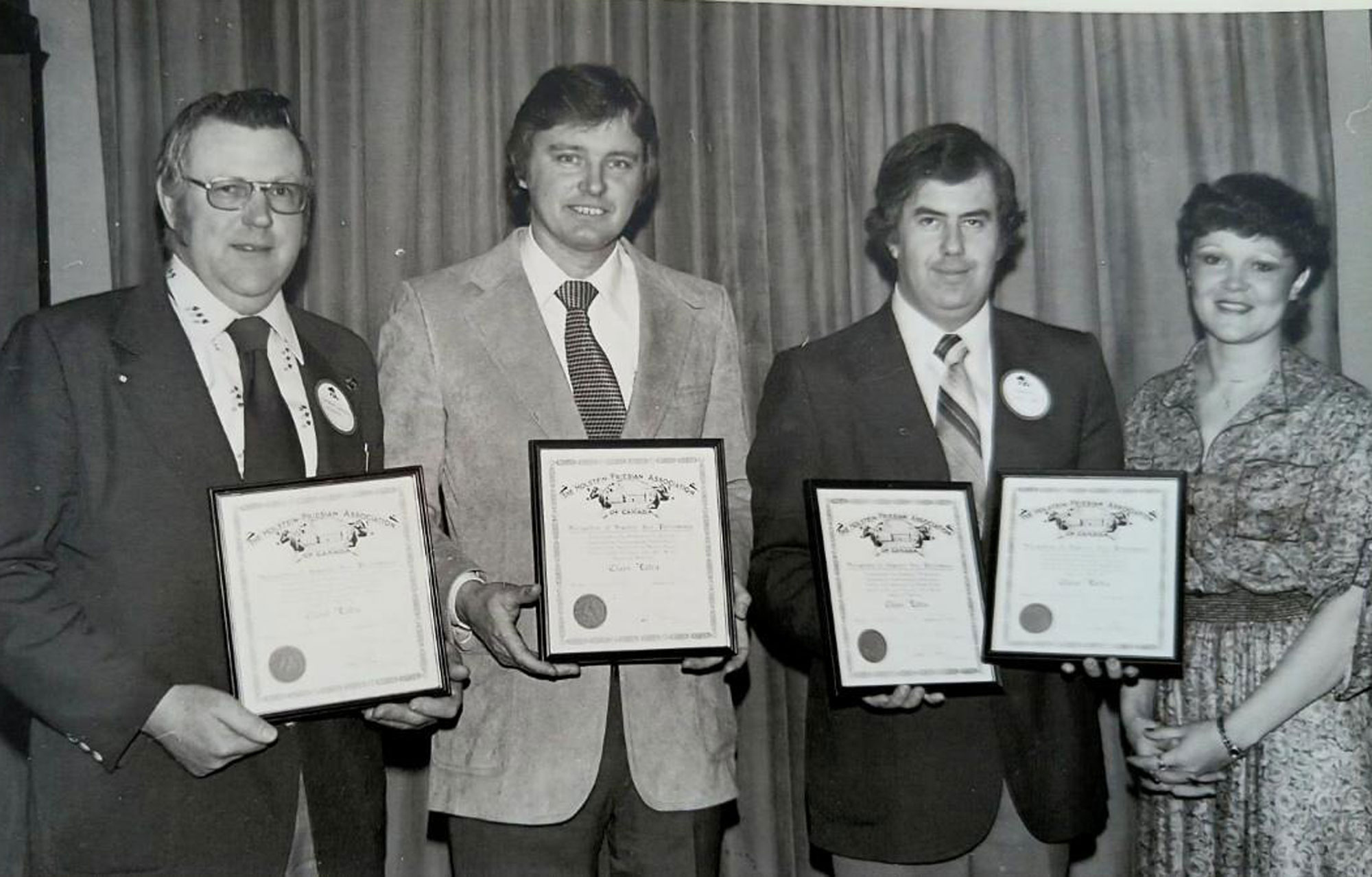

The results vindicated his balanced approach. Of the first seven young bulls submitted to the CIAQ testing program, three achieved the coveted recognition of EXTRA bull from Holstein Canada. Breeders began noticing that test bulls’ offspring stood out at shows. Visitors—Canadian and foreign—arrived regularly to inspect the daughters of the emerging stars. The momentum was building.

But the ultimate test of Chicoine’s numbers-over-narratives philosophy was already in the barn, waiting to prove him right—or destroy his credibility entirely.

Senator’s Vindication

When Robert Chicoine spotted the advertisement in the October 10, 1967, issue of Holstein World, his attention was immediately fixed on the pedigree. A young bull named Craiglen Sevens Senator was being offered in the dispersal sale of American auctioneer Harris Wilcox’s herd in New York state. The calf’s maternal grandmother, mother, and sire were all connected to bulls that showed progeny proofs with positive indices in both production and conformation from artificial insemination programs. His sire was Sevens Burke Skylark; his dam’s sire was Osborndale Ivanhoe; his second dam was a Burkgov Inka Dekol.

“I had never seen such an eloquent pedigree on the male side,” Chicoine recalled.

But the dam’s photograph told a different story. She lacked the dairy character that breeders prized, appearing disappointing in ways that would ordinarily disqualify her offspring from serious consideration. Still, the indices were too compelling to ignore. CIAQ decided to attend the auction but to make a strict evaluation of the mother’s actual conformation before deciding whether to bid.

On-site, Chicoine’s team quickly determined that the dam was far superior to what her photograph suggested. Her mammary system was excellent, and their concerns about dairy character proved unfounded. That day, while one of New York’s most renowned herds won the bidding for the mother, CIAQ became the owner of her young son.

Henceforth, the bull would carry the semen identification code 73HO101 Senator.

When the time came to offer him for testing, CIAQ prepared promotional materials highlighting the richness of the indices in his pedigree. The hope was that breeders would look past the mother’s modest production records and disappointing photograph to see the genetic potential revealed by the comparison numbers.

The hope was misplaced. Most breeders ignored the young bull entirely. The reservations were multiple: the dam’s appearance, her unremarkable production figures, and most frustratingly, the speckled coat that would require tedious hand-drawing on registration forms. The pattern terrified breeders who could imagine hours spent trying to reproduce those mottled markings.

CIAQ instructed its inseminators to always try to use Senator when a farmer requested a test bull without making a specific selection. A humbling workaround, and there were real fears that he’d never accumulate enough daughters under official control to achieve an official proof.

Then the numbers started coming in.

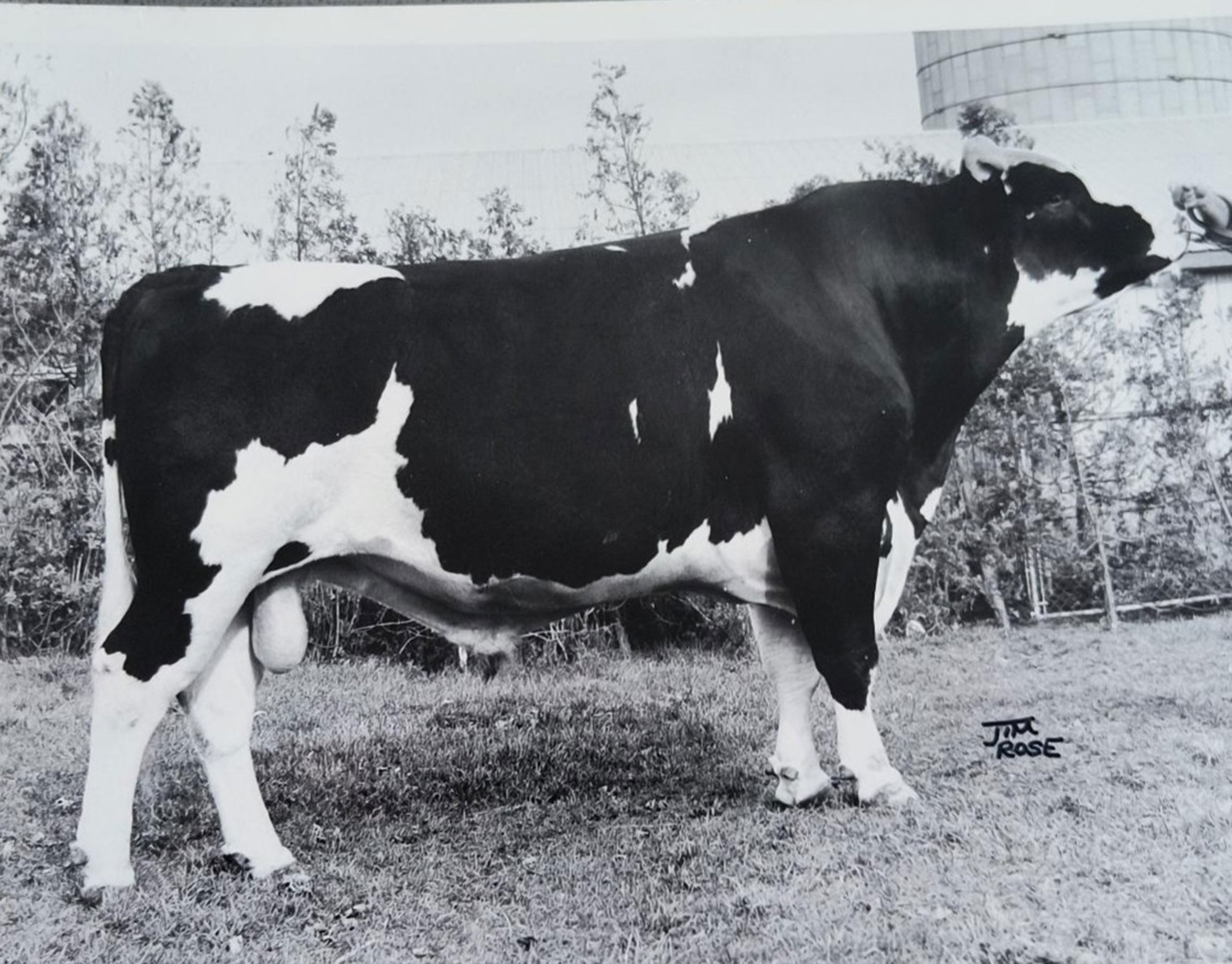

The genetic evaluations published in February 1973 assigned 22 daughters to Senator with positive production results. He also posted positive results in conformation. CIAQ put him back into service, presuming that his true potential exceeded what the small daughter sample revealed. As more evaluations arrived and his proof strengthened, his use as a proven bull gradually increased.

Finally, in 1978, Holstein Canada awarded 73HO101 Craiglen Sevens Senator the coveted recognition of Extra bull. The strong potential that his pedigree had promised finally expressed itself in undeniable form.

Yet Senator’s destiny remained tragic in certain ways. A health test returned doubtful results, and after repeated trials at the doubtful level, CIAQ removed him from the bull stud. His semen reserves were quickly exhausted just as elite breeders were beginning to take notice. He also left a few daughters who attracted attention at exhibitions.

But genetics has a longer memory than markets.

The most famous of Senator’s daughters was Proulade Ruth Senator, who at age four captured Grand Champion honors at the Quebec provincial exhibition in 1981 and earned an All-Canadian nomination that same year. In a profile of Pierre Boulet published in Holstein International, the legendary breeder credited his lifelong passion for Holsteins to his adolescence, when he helped care for and prepare that very cow for shows.

“I remember that upon reading this article, I made the reflection that if 73HO101 Senator had only sired one female who inspired the awakening of the career of the now legendary Pierre Boulet, he would have done useful work for the Holstein breed,” Chicoine observed.

But Senator’s influence extended far beyond one inspiring daughter. Several important Quebec cow families that trace back to his era carry his genetics. The most significant is surely Comestar Laurie Sheik, whose third dam was sired by Senator. (The cow Chicoine called “the best kept secret of Quebec Holstein breeding of the last 50 years.”)

Rosiers Blexy Goldwyn Ex-96, the magnificent cow who was Grand Champion at both the International Holstein Show and the Royal Winter Fair in 2017, has one of her maternal ancestors sired by a son of Senator. Eastside Lewisdale Gold Missy Ex-95, who captured Grand Champion honors at Madison and Toronto in 2011, traces her lineage to Senator twice.

“It appears to me that more than 50% of Canadian subjects whose documented ancestry goes back to the time when 73HO101 Senator was in service feature his presence in their pedigree,” Chicoine estimated. “He may have been Québec Holstein breeding best kept secret of the 70s and the 80s,” he added.

The lesson from Senator’s story became a foundational principle: favorable indices with high repeatability in an individual’s pedigree were an important indicator of the animal’s genetic potential—far better than the mother’s phenotypic production values. But Chicoine also learned a pragmatic corollary: for a testing program to function effectively, young bulls’ dams must have phenotypic values impressive enough to excite breeders and ensure participation.

The indices had triumphed over impressions. But the revolution was only beginning.

Breaking the Star Brood Cow Rule

Senator’s vindication loosened one knot of tradition, but an even more stubborn one remained. For as long as anyone could remember, the dairy industry operated under an unwritten rule: a potential test bull’s mother had to be at a minimum classified Very Good, preferably old enough to have established herself through her progeny, and ideally being already recognized as a proven brood cow.

The logic seemed sound. Before superovulation and embryo transfer became commercial practices, a cow needed years to produce enough offspring to demonstrate her breeding value. By the time she earned the coveted Star Brood Cow designation, she might be nearly ten years old—and if she’d given birth to mostly males in her early years, she might not even still be alive.

When Chicoine once asked a prominent breeder—who’d later become president of Holstein Canada—whether an exception could be made for an exceptional young cow who’d suffered an accident preventing her from reaching the desired classification level, the reaction was immediate and absolute.

“It was out of the question!”

No discussion. No consideration. Just… no.

So deeply ingrained was this belief that it took CIAQ twenty years to build the institutional confidence to challenge it. Think about that—twenty years of knowing the rule was probably costing them elite genetics, but not having the nerve to buck convention. The breakthrough finally came when the organization dared to test sons from a promising young primiparous cow classified only Good Plus at 84 points—below the traditional Very Good threshold.

You can imagine the anxiety in those hallways. What if the traditionalists were right? What if this gamble destroyed the program’s credibility?

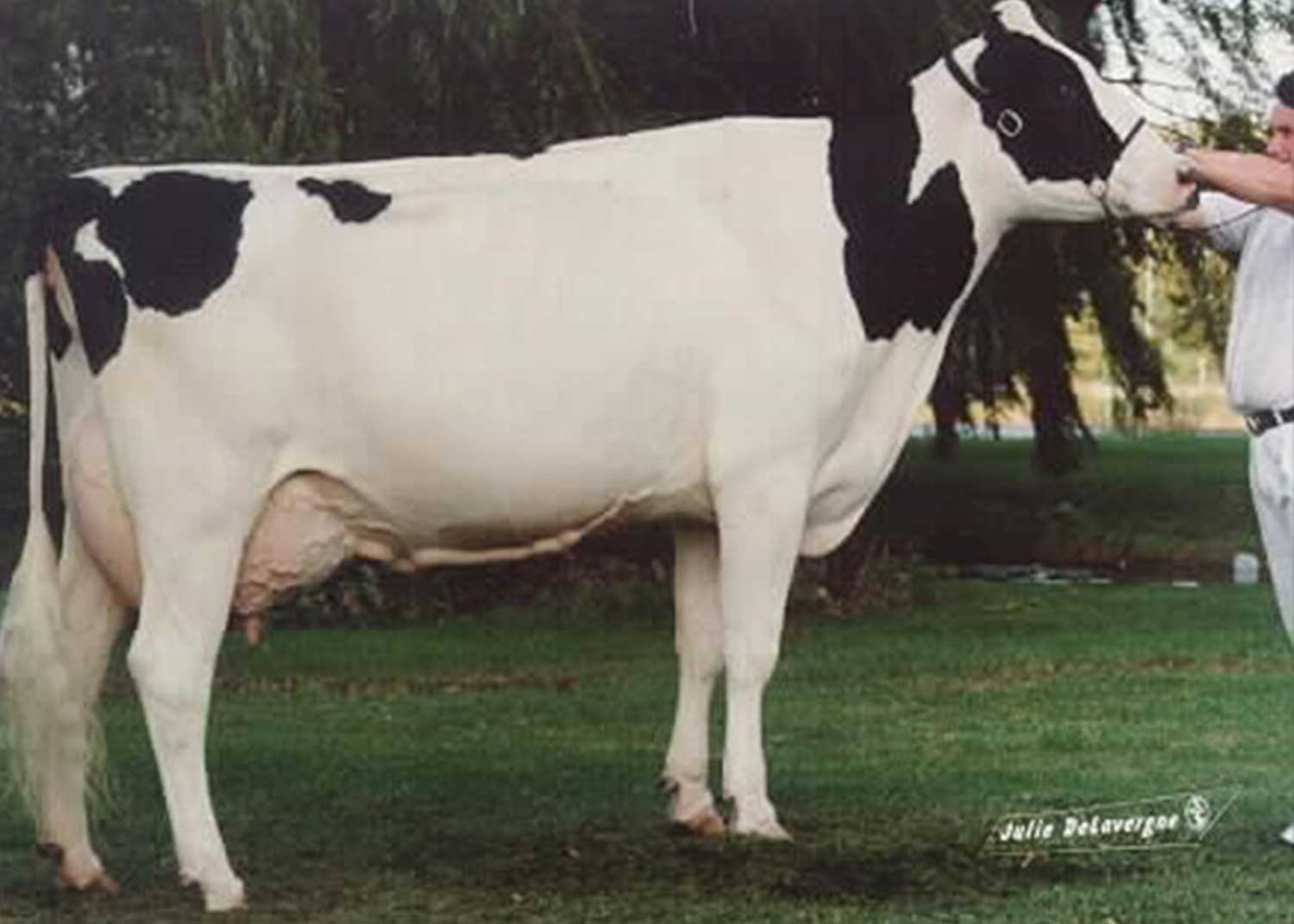

Two bulls emerged from this audacious decision: Comestar Lee and Comestar Top Gun.

Both achieved Extra bull status from Holstein Canada. But here’s where it gets remarkable—Comestar Lee transcended his origins to become one of the most used bulls in the entire history of the Holstein breed. 1.5 million doses of semen were distributed around the world.

Let that sink in. A bull from a dam who didn’t meet the traditional standard. A dam the old guard would’ve dismissed out of hand. And his genetics went everywhere.

The phones at CIAQ must have been ringing off the hook when those proofs came back. The breeders who’d insisted on the Star Brood Cow rule—what could they say? The evidence was undeniable. Sometimes the most valuable discoveries await those willing to break sacred rules.

From Prosperity to Innovation: Boviteq

The testing program’s success created something rare in cooperative agriculture: a surplus. The identification of particularly popular bulls, such as Glenafton Enhancer, Hanoverhill Starbuck, and Kingstead Valiant Tab, generated revenues that exceeded all expectations.

Chicoine saw an opportunity—and for him, this wasn’t just institutional strategy. It was personal. If CIAQ had mastered the male side of the genetic equation through rigorous data analysis, why shouldn’t the female side deserve the same scientific approach?

Thus, Boviteq was born in 1986 with a clear mandate: research. At the time, frozen embryos rarely achieved acceptable fertility rates when implanted. Boviteq’s first mission was to improve those results—a challenge that still resonates today as IVF continues transforming how progressive dairies approach reproduction.

The new entity faced immediate resistance from three directions. The veterinary faculty at the University of Montreal believed research funds in embryology rightfully belonged to them. Veterinarians specializing in embryo collection feared a new competitor. And breeders worried that Boviteq would eventually compete with them in embryo sales.

Chicoine’s solution required structural creativity. Boviteq became a subsidiary with its own board of directors and independent management. Ann Louise Carson was appointed general manager, bringing competence and diplomacy to smooth over tensions with industry partners. Gradually, Boviteq came to be seen as a natural part of the Quebec cattle breeding community.

Looking at where Boviteq and genomics have taken us today—with gender-sorted semen commonplace and sexed embryos increasingly viable—Chicoine’s bet on female-side research seems almost prophetic.

The Alliance Forged in Crisis

If Boviteq was born from prosperity, the Semex Alliance was forged in fire.

The seeds were planted in September 1988, at a seminar on Canadian genetics in Rennes, France. Robert Chicoine and Doug Blair, CEO and owner of Western Breeders Service in Alberta, found themselves discussing a persistent vulnerability: a small regional center might not always have star bulls to market, leaving it financially exposed during lean genetic years.

Blair proposed an income-sharing arrangement among Canadian centers based on each center’s share of the breed’s numbers. By pooling resources, partners could smooth out the inevitable fluctuations in genetic fortune. By January 1990, WBS, BCAI, and CIAQ signed an agreement, and Genexcel became a reality.

The early years proved the concept in an unexpected way. CIAQ, which had enjoyed brilliant success with Starbuck and his herdmates, found itself without star performers among Starbuck’s sons, while its Genexcel partners identified great stars among their Starbuck offspring. The smaller partners supported CIAQ during its dry spell, demonstrating that the sharing principle could work even when the founding major-partner organization was in need of help.

Then everything changed. Western Breeders acquired the American center Landmark Genetics, creating Alta Genetics and fundamentally altering the landscape.

Suddenly, Western Breeders possessed its own international distribution network and announced its intention to leave the Semex Canada export structure. They offered to integrate Semex Canada into Alta’s global system, with one condition that proved insurmountable: the remaining Canadian partners wanted a majority stake in any merged entity. Alta wouldn’t yield control.

The negotiations were intense. Two sessions of back-and-forth, positions hardening, stakes climbing. Finally, the Alta board chairman announced that the parties’ positions were irreconcilable.

Hours later, Semex Canada’s general manager—who’d supported Alta’s proposal—tendered his resignation and left the same day. Just walked out.

“It was quite a dramatic situation,” Chicoine recalled, “since we, the partners in Semex who had just refused Alta’s offer, did not have a clearly defined plan for the future.”

Picture that moment. The key negotiation has collapsed. Your general manager just quit. International competition is intensifying. And you’re sitting there with your partners—CIAQ, BCAI, Gencor, and EBI—looking at each other, knowing that fragmentation might mean the end of Canadian genetics’ global competitiveness.

“We don’t have a clear plan,” someone likely said.

“Then we make one,” came the response. “In the meantime, let’s try to carry on as effectively as possible.” Wilbur Shantz, who had recently retired from United Breeders, was appointed interim general manager.

Chicoine and Gordon Souter championed a radical solution: pool the ownership of all bulls into a single new legal entity. Unlike Genexcel, where a one-year notice allowed any partner to exit, this new alliance would be structured to make departure extremely difficult. The cooperative model they championed anticipated the consolidation pressures many operations face in 2025—the understanding that fragmented players can’t compete against consolidated giants.

On January 1, 1997, the Semex Alliance became a reality.

“A picture of Wilbur Shantz and the four general managers of the Semex Alliance founding centres that was taken to mark this new beginning and symbolize their willingness to cooperate mutually is particularly dear to my heart,” Chicoine reflected.

That photograph captured not just five men, but the end of an era of regional competition and the beginning of unified Canadian genetic excellence on the world stage. Looking at Semex’s global presence today—still a major force despite intense competition from American and European programs—you can trace it directly back to that moment of crisis that became an opportunity.

The Long Ripple of One Breeding Decision

Among the many decisions Robert Chicoine made during his career, one stands out for the extraordinary distance between his actions and their impact.

In late spring of 1972, Chicoine stopped at the Sunnylodge farm while the cows were on pasture. His attention was immediately captured by a cow named Sunnylodge Janice. She possessed good general conformation and a remarkably well-preserved quality udder, despite her very superior production for her era. Her pedigree was heavily concentrated on the Rag Apple line, particularly the Montvic Rag Apple Ajax branch, known for transmitting excellent udders.

Chicoine proposed a contract mating to owner Carl Smith. The bull selected was No-Na-Me Fond Matt, whose pedigree was equally rich in the Rag Apple line. In May 1973, the mating produced a bull calf named Sunnylodge Jester.

Jester’s testing results were positive in both production and conformation, earning him regular service for a time. But his timing was cruel. He was negative for size and stature at the precise moment when Quebec breeders were working hardest to improve those very traits. His popularity suffered accordingly, and his influence on the breed remained limited.

By conventional measures, the mating that produced Jester was a modest success at best.

But the story didn’t end there.

The following year, Sunnylodge Janice was bred again to Fond Matt. On July 1, 1974, this repeat mating produced a heifer named Sunnylodge Fond Vickie.

Decades would pass before her true significance emerged.

On January 3, 2000, Sunnylodge Fond Vickie became the seventh dam of Braedale Goldwyn—one of the most unique and spectacular bulls in modern Holstein history.

The mating of Chicoine, arranged on an Eastern Ontario farm in 1972, rippled through seven generations to help produce a global genetic legend. It’s a perfect illustration of how vision in dairy breeding operates on timescales that dwarf human careers—and how the most impactful decisions may not reveal their significance for decades.

Something to think about when you’re making breeding decisions on your own operation today.

The Philosophy That Guided Everything

Throughout his career, Robert Chicoine returned to a single guiding principle when facing difficult decisions: “Necessity is the law.”

“It has nothing to do with not respecting the law,” he explained. “In a difficult situation, seeking to find the best possible solution becomes the rule to which one must adhere without hesitation.”

This pragmatism shaped his handling of every crisis, from the early skepticism toward young sire testing to the high-stakes negotiations that forged the Semex Alliance.

His core management philosophy: “Surround yourself with the most competent people possible, create a healthy and warm working climate, and analyze regularly and seriously the challenges that the company must face as well as the opportunities offered by the industry.”

Not a bad framework for anyone running a dairy operation in 2025, honestly.

One experience taught him how to apply this philosophy to failure. CIAQ invested heavily in recruiting over 1,000 new herds into milk recording programs, aiming to expand the testing pool. The initial results were painful—no star bulls emerged even as competitors identified legends from their Starbuck offspring. The board questioned whether to abandon the effort.

Chicoine argued for patience. The program’s design was sound; immediate results didn’t invalidate the long-term strategy. CIAQ persevered, and eventually the genetic evaluations of July 1996 vindicated the decision—identifying global superstars like Startmore Rudolph and Maughlin Storm.

His advice: “After having planned a project well and executed it rigorously, one should not throw in the towel too quickly if the results do not meet expectations.”

Words worth remembering when genomic predictions don’t pan out the way you expected, or when a highly-indexed young sire disappoints…

In retirement, Chicoine pursued the passions that shaped his youth—exploring the national parks of the Canadian and American West and playing bridge once or twice a week. But one hobby directly connected to his life’s work: spending countless hours tracing Holstein pedigrees back to their foundation animals and analyzing the combinations that produced exceptional individuals. He created a fund supporting graduate students at Laval University who chose the field of genomics.

“I can summarize my career by saying that I am blessed to have always been passionate about my work,” he reflected. “I went to work with enthusiasm daily.”

The Bottom Line

Today, when commercial farmers achieve rapid genetic progress in functional conformation and milk components through genomic selection, they’re building on foundations that Robert Chicoine helped lay. When breeders evaluate young sires through data-driven indices rather than subjective appearance, they’re practicing principles he championed when they were still controversial. When Canadian genetics enjoys global prestige under the Semex banner, they’re benefiting from an alliance he helped forge from crisis.

And somewhere in the DNA of perhaps half of all contemporary Canadian Holsteins, the genetics of a speckled bull that nobody wanted continue to flow.

The next time you trust an index over a photograph—whether it’s an LPI ranking or a health trait evaluation—you’re walking the path Chicoine cleared. That’s not just history. That’s the foundation of every breeding decision you’ll make tomorrow.

Key Takeaways:

Trust Data Over Appearances

- Indices beat photographs. Senator’s stellar pedigree predicted genetic greatness despite his dam’s disappointing picture—a principle that now powers every genomic ranking you trust.

- Environment masks genetics. An 8,000 kg cow in a top-management herd isn’t genetically superior to a 7,500 kg cow under average conditions. Strip away the environment to reveal true merit.

- Challenge sacred rules. The Star Brood Cow requirement seemed untouchable until CIAQ tested sons from a primiparous Good Plus cow—producing Comestar Lee with 1.5 million doses distributed worldwide.

Lead Through Crisis

- “Necessity is the law.” When Semex Canada faced collapse, Chicoine built consensus around a radical solution: pooling all bulls into a single alliance that still dominates global markets 30 years later.

- Convert skeptics through results, not arguments. Instead of labeling resistant breeders as heretics, he mailed pedigrees, presented data, and let observation change minds organically.

Play the Long Game

- Don’t abandon well-designed projects at the first disappointment. Operation Identification produced no star bulls initially—then delivered Startmore Rudolph and Maughlin Storm, global legends that vindicated years of perseverance.

- Failure seeds future success. Those early struggles exposed the risks of operating solo and directly informed the thinking that created the Semex Alliance.

- Genetics operates on generational timescales. A mating Chicoine arranged in 1972 rippled through seven generations to produce Braedale Goldwyn—proof that your best breeding decisions may not reveal their impact for decades.

Balance Progress with Practicality

- Production without conformation fails. A testing program that ignores type will see physical quality regress—and lose the breeder participation it needs to function.

- Select for sustainability without sacrificing productivity. On methane: give the trait all possible importance without significantly altering progress on other characters—otherwise, you need more animals to produce the same milk.

Executive Summary:

The dairy industry’s most influential genetic legacy began with a bull nobody wanted. In 1967, Quebec breeders dismissed 73HO101 Senator because his dam’s speckled coat meant hours of tedious hand-drawing on registration forms—yet his genetics now flow through more than half of contemporary Canadian Holsteins, including Madison Grand Champions Braedale Goldwyn and Eastside Lewisdale Gold Missy. Robert Chicoine spent six decades proving that indices beat photographs, breaking the sacred Star Brood Cow rule to produce Comestar Lee (1.5 million doses sold worldwide) and forging the Semex Alliance from a corporate crisis that saw the general manager walk out the same day negotiations collapsed. The same principle that vindicated Senator—trusting pedigree data over phenotypic impressions—now powers every genomic ranking guiding your breeding decisions. The next time you dismiss a high-indexed bull because his dam’s photo disappoints, remember: that’s exactly how Senator was treated, and he went on to shape the modern Holstein breed.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Celebrating 50 Years of Semex: A Symbol of Genetic Progress and Technological Innovation – If Robert Chicoine was the architect of the alliance, these men were the fellow builders who helped Canada dominate the world stage. Discover the other pioneers who turned a regional cooperative into a global genetic powerhouse.

- When Lightning Strikes: The Braedale Goldwyn Story That Changed Everything – The ripple effect of Chicoine’s 1972 mating didn’t stop at a single heifer; it led to the bull that eventually rewrote the Holstein playbook. Dive into the deep genomic analysis of how Goldwyn truly conquered the world.

- FERME PIERRE BOULET: First Comes Love Then Comes Genetics – Chicoine often reflected that if Senator only inspired one breeder, his work was worth it. This profile of Pierre Boulet—whose legendary career was sparked by a Senator daughter—is the living, breathing proof of that enduring legacy.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!