Dairy farmers found a way to keep $228K that would go to the IRS. It’s legal, it’s smart, and bankruptcies are up 55%. Here’s how.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Dairy farmers have discovered that filing bankruptcy can net them $228,000 more than selling their farms outright—and 259 operations did precisely that in the past year, driving a 55% surge in Chapter 12 filings. The catalyst is Section 1232, a 2017 tax provision that treats capital gains as dischargeable debt, turning a $285,600 IRS bill into just $57,120 for a typical Wisconsin farm sale. These aren’t failures but strategic exits by producers facing 8% interest rates and margins squeezed to breakeven who see no point grinding through more unprofitable years. While this tax-advantaged bankruptcy helps retiring farmers preserve decades of equity building, it’s fundamentally reshaping the industry. Young farmers without inherited land face nearly insurmountable entry barriers, and production is rapidly consolidating in states like Texas, where operations compete on efficiency rather than land appreciation. The result: bankruptcy has become a financial planning tool as strategic as any breeding decision or ration formulation.

You know, when the University of Arkansas Extension released their recent data showing 259 dairy farms filed for Chapter 12 bankruptcy between April 2024 and March 2025—that’s a 55% jump from the previous year—most of us in the industry took notice. But here’s what’s really interesting: the more I dig into these numbers, the more I’m seeing something unexpected happening out there.

Many of these filings don’t look like the desperate collapses we’ve seen before. Not at all. What we’re actually witnessing is strategic financial planning, and it all ties back to a 2017 tax law change that most of us didn’t pay much attention to when it passed.

Now, let me be clear about something important: these aren’t wealthy farmers gaming the system. Most of these operations are facing real financial pressure—margins have been squeezed to breakeven or worse for many producers. When you combine operating loan rates jumping from 3% to nearly 8% (Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago data), input costs that never came back down after their spike, and milk prices that the USDA reports are back at 2018-2019 levels, a lot of operations are genuinely struggling. The difference is that Section 1232 gives them a strategic exit option that preserves more value than grinding it out for another few unprofitable years would.

“I’ve milked cows for 35 years. I’m not failing—I’m choosing the smartest path forward for my family with the rules as they exist. If that means using bankruptcy court to maximize our retirement after decades of 4 a.m. milkings, I’m at peace with that decision.” — Wisconsin dairy farmer preparing for strategic Chapter 12 filing.

What’s Actually Happening with These Numbers

So let me share what I’ve been learning about the current situation. You probably know this already, but today’s economic are fundamentally different from previous downturns. Back in 2019, when USDA’s Economic Research Service documented 599 Chapter 12 filings nationally, we all understood what was happening—milk prices had absolutely tanked, and those trade wars were killing our export markets. It was straightforward and brutal.

Today? Well, it’s more nuanced. Ryan Loy from the University of Arkansas’s Division of Agriculture puts it well—commodity prices have basically returned to those 2018-2019 levels, yet our input costs…they never came back down. Fertilizer, feed, diesel—they’re all still elevated, and we’re all feeling that squeeze.

But here’s what’s really changed the game for a lot of operations: interest rates. The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s agricultural finance data shows operating loan rates essentially doubled between 2021 and 2023. We went from around 3% to nearly 8% by mid-2025.

And if you’re like many producers who expanded with variable-rate financing when money was cheap…well, you know exactly what that means for your monthly payments.

The regional patterns we’re seeing are worth noting too:

- First quarter 2025 brought us 88 Chapter 12 filings nationally—that’s nearly double Q1 2024’s 45 filings

- Arkansas went from 4 filings in 2023 to 25 in 2025—that’s quite a shift

- Michigan moved from zero in 2023 to 12 in 2024

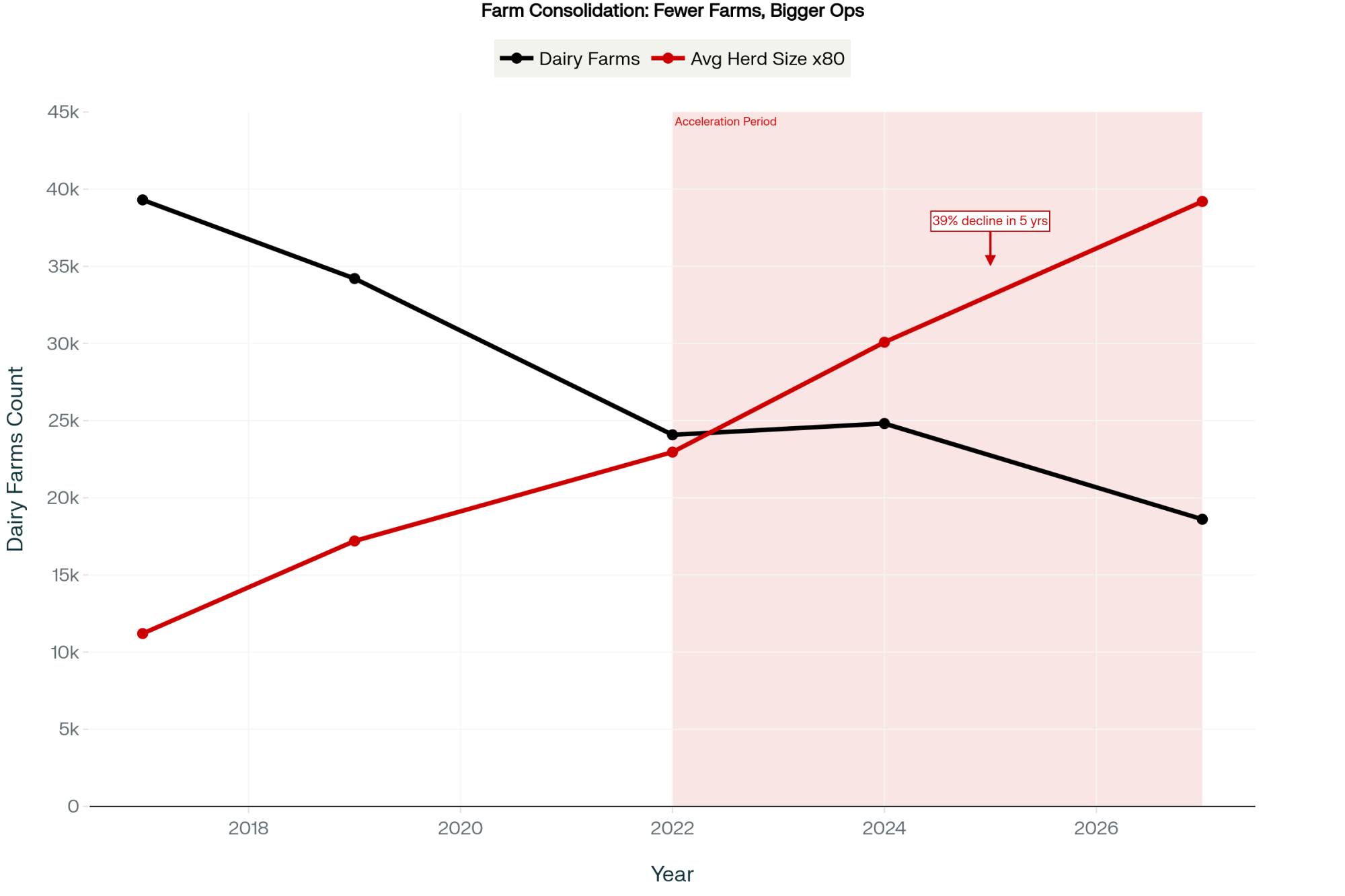

- Wisconsin, as many of you know, lost another 400 operations in 2024, bringing them down to 5,348 licensed herds

Understanding Section 1232 and Why It Matters

Now, here’s where things get particularly interesting—and if you haven’t heard about this yet, you’ll want to pay attention even if bankruptcy’s the last thing on your mind.

Remember the Supreme Court’s Hall v. United States case back in 2012? Lynwood and Brenda Hall sold their farm for $960,000 during bankruptcy, triggered about $29,000 in capital gains taxes, and the court basically said, “you’ve got to pay that in full before we’ll approve your reorganization plan.” It made Chapter 12 pretty much useless for anyone with appreciated land.

Well, Senator Chuck Grassley from Iowa—he’s been a friend to agriculture for years—pushed through the Family Farmer Bankruptcy Clarification Act in October 2017. This added Section 1232 to the bankruptcy code, and honestly, it’s a game-changer.

Dr. Kristine Tidgren, who runs Iowa State’s Center for Agricultural Law and Taxation, explained this really well in her 2020 analysis. Unlike Chapter 11 bankruptcies, where you’d have to pay capital gains in full, Chapter 12 now treats those tax obligations as general unsecured debt. That means they can potentially be discharged—either partially or sometimes entirely—through your reorganization plan.

Let’s Walk Through the Math Together

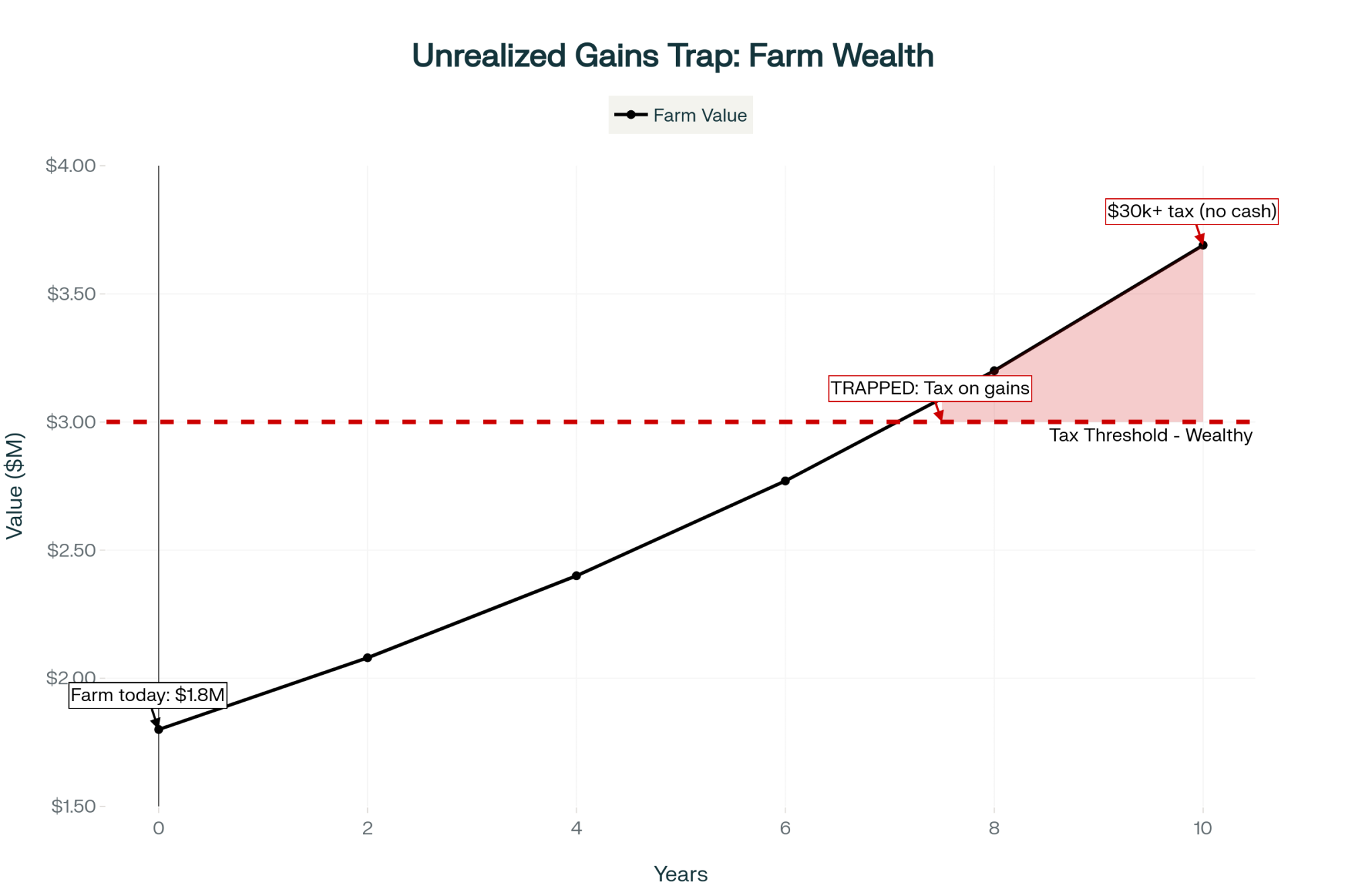

So here’s a real-world scenario using Wisconsin farmland values from the USDA’s August 2025 data. Say you’re a producer who purchased 200 acres in 2005 for $2,000 an acre—pretty typical for that time. According to the Wisconsin Realtors Association, that same ground’s worth about $8,000 an acre today.

Traditional Sale (Outside Bankruptcy):

| Item | Amount |

| Sale proceeds | $1,600,000 |

| Capital gain | $1,200,000 |

| Federal capital gains tax (20%) | $240,000 |

| Net investment income tax (3.8%) | $45,600 |

| Total tax to IRS | $285,600 |

| Net proceeds after tax | $1,314,400 |

Strategic Chapter 12 Filing with Section 1232:

| Item | Amount |

| Sale proceeds | $1,600,000 |

| Tax becomes unsecured debt | $285,600 |

| Payment to unsecured creditors (20%) | $57,120 |

| Tax savings | $228,480 |

| Net proceeds | $1,542,880 |

See how Section 1232 flips the tax equation for dairy producers: from IRS bill to retirement nest egg—making Chapter 12 a strategic tool. This isn’t just about bankruptcy—this is smarter farm succession!

Scenario | Sale Proceeds | Total Tax Paid | Net Proceeds | Strategic Tax Savings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Sale | $1,600,000 | $285,600 | $1,314,400 | $0 |

| Chapter 12 w/ Section 1232 | $1,600,000 | $57,120 | $1,542,880 | $228,480 |

Now, that’s real money. And when you’re looking at those numbers…it makes you think differently about what bankruptcy means, doesn’t it?

The Wisconsin Story: It’s Not What Most People Think

Mike Vincent, the ag economist at UW-Madison’s Extension, shared something with me that really stuck: “The biggest issue we’re facing is that the farmers are retiring.”

And you know what? The data backs him up completely.

In 2020, UW-Madison and USDA NASS conducted the Dairy Farm Transition Survey. What they found was eye-opening—17% of Wisconsin dairy farms said they wouldn’t be milking within five years.

For smaller operations — those with under 100 cows — the number jumped to 22%. And here’s the kicker: only 40% of Wisconsin dairy farmers had identified someone to take over the operation.

So when Mike says he’s not surprised by these closure numbers, he’s got a point. Many of these aren’t panic exits at all. They’re planned transitions that just happen to coincide with bankruptcy provisions that make Chapter 12 filing financially smart.

I was talking with a producer up in Shawano County recently—been milking for 35 years, profitable most years, but his kids aren’t interested in taking over. His land’s worth four times what he paid for it. He asked me straight up: “Why would I leave $200,000 on the table for the IRS when I could use that for my retirement?”

And honestly? I couldn’t give him a good reason not to consider it.

Who Benefits and Who Doesn’t—The Regional Differences

What’s fascinating is how differently this plays out across regions. According to USDA NASS’s August 2025 land value data, if you’re farming in Iowa, where land’s averaging $10,200 an acre, or Illinois at $9,850, or certain parts of Wisconsin ranging from $6,800 to $18,500…well, you’ve got options that other producers don’t.

The National Agricultural Law Center’s been tracking filing patterns, and they’re seeing it’s mostly farmers over 60 planning retirement, operations needing to downsize—maybe from 300 cows to 150 or 200—and family farms where the next generation just isn’t interested in continuing.

But here’s the thing: if you’re running a modern operation in Texas or New Mexico, where most producers lease their ground—Texas A&M AgriLife Extension reports the average operation there leases about 70% of their cropland—this doesn’t help you at all. Same story if you bought land recently, or if you’re in a state like New Mexico where USDA data shows land’s only worth about $725 an acre.

A Texas producer I know who’s managing 2,100 cows near Amarillo put it pretty bluntly: “We compete on production efficiency, not land equity. This Section 1232 stuff means nothing to us.” And she’s absolutely right—it’s a completely different business model.

Now, in the Northeast, it’s another story entirely. Vermont and New York operations often sit on land that’s appreciated significantly due to development pressure, but they also face some of the highest production costs in the country.

A producer from St. Albans, Vermont, told me recently that while his land’s worth more than ever, the combination of labor costs and environmental regulations means he’s still weighing whether strategic bankruptcy makes sense compared to a traditional sale.

A Young Farmer’s Perspective

I recently connected with Jake Martinez, a 29-year-old who started a 180-cow operation in central Minnesota in 2022. His take on all this was eye-opening.

“I’m watching neighbors who’ve been farming for 40 years walk away with tax-free gains while I’m trying to scrape together enough for a down payment on 80 acres,” Jake told me. “Don’t get me wrong—they earned it. But for someone like me trying to build something from scratch? The entry barriers just keep getting higher.”

Jake’s financing his expansion through custom heifer raising and a small on-farm cheese operation. “I can’t compete on land acquisition,” he explained. “So I’ve got to find other ways to build equity. Direct marketing, value-added production—that’s where young farmers like me have to look for opportunities.”

His perspective highlights something important: while Section 1232 helps retiring farmers maximize their exit value, it’s creating an even wider gap for the next generation trying to get started.

How Word Is Spreading Through the Industry

What’s really accelerated this trend is the education happening through agricultural networks. The National Agricultural Law Center at the University of Arkansas reported in its FY2024 annual report that it hosted 16 webinars attended by over 2,400 people. Sessions on agricultural bankruptcy and debt management are drawing standing-room-only crowds at farm conferences these days.

Joe Peiffer, who runs Ag & Business Legal Strategies in Iowa—he grew up on a Delaware County dairy farm himself—has been particularly vocal about this. He makes a good point: “The producers who are decisive and adapt to changing conditions have the best opportunity to remain viable.”

There’s also Russell Morgan, an agricultural consultant in Arkansas, who’s been working with Chapter 12 trustee Renee Williams to educate Mid-South farmers. I heard their April 2025 webinar drew a huge crowd—dairy and row crop producers all trying to understand their options.

What the Lenders Are Thinking

Now, you might wonder what lenders think about all this. Bob Mikell from AgSouth Farm Credit shared some interesting thoughts at the recent Mid-South Agricultural and Environmental Law Conference.

He basically said they’d rather see a farmer successfully reorganize through Chapter 12 than lose everything in foreclosure. If Section 1232 helps someone right-size their operation and keep farming, he sees that as better for everyone involved.

That’s not universal, of course. Some commercial banks aren’t thrilled about strategic Chapter 12 filings by solvent borrowers. But the Farm Credit System—they hold about 47% of total farm real estate debt according to USDA’s Economic Research Service—seems to be taking a pretty pragmatic approach to the whole thing.

Looking North: How Canada Does Things Differently

It’s worth comparing our situation to what’s happening in Canada, because it really highlights the trade-offs we’re dealing with. Statistics Canada shows Canadian dairy farms maintain debt-to-asset ratios around 0.191—that’s about half what we typically see in comparable U.S. operations. Bankruptcies? They’re basically non-existent up there.

While we’re dealing with volatility and needing various support programs, their supply management system provides built-in stability. But—and this is a big but—that stability comes at a cost. Canadian Dairy Commission data from November 2024 shows quota costs running CAD $24,000 to $58,000 per cow’s worth of production capacity. A typical 100-cow operation needs $3-5 million just in quota before they buy their first animal. And consumers? They’re paying CAD $1.07 per liter for milk.

Meanwhile, we’ve got the freedom to expand and chase export markets. U.S. Dairy Export Council data shows we hit $8.22 billion in exports in 2024. But with that freedom comes the volatility that’s driving these bankruptcy patterns we’re seeing.

Country/Region | Entry Barrier | Producer Age (avg) | Bankruptcy Incidence | Milk Price (USD/L) | Export Ratio | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada (Quota) | $30,000/cow quota | 55+ | Rare | $0.80-1.10 | <10% | High startup cost |

| USA (Free Market) | $400,000+ down | 60+ | Up 55% (2024) | $0.40-0.60 | 15%+ | Volatility, consolidation |

| Texas/Idaho (Efficiency) | Leased land, $250K+ equity | 50-58 | Low, not equity-driven | $0.40-0.55 | 20%+ | Scale, tech adoption |

The Personal Side of These Decisions

I think it’s important to acknowledge something here: not everyone’s comfortable with strategic bankruptcy, even when the math makes perfect sense.

A producer from Fond du Lac County recently told me that his grandfather would “roll over in his grave” if he filed for bankruptcy, regardless of the circumstances. “In his day, you paid your debts, period.” That sentiment’s real, and it matters in our communities.

At the same time, Jamie Dreher from Downey Brand LLP made a good point at the Western Water, Ag, and Environmental Law Conference this past June. Congress designed Section 1232 specifically to help farmers transition without getting crushed by tax obligations. Using a tool that was created for your exact situation? There’s no shame in that.

It’s a deeply personal decision. There’s no right answer that works for everyone’s values and circumstances.

Where This Is All Heading

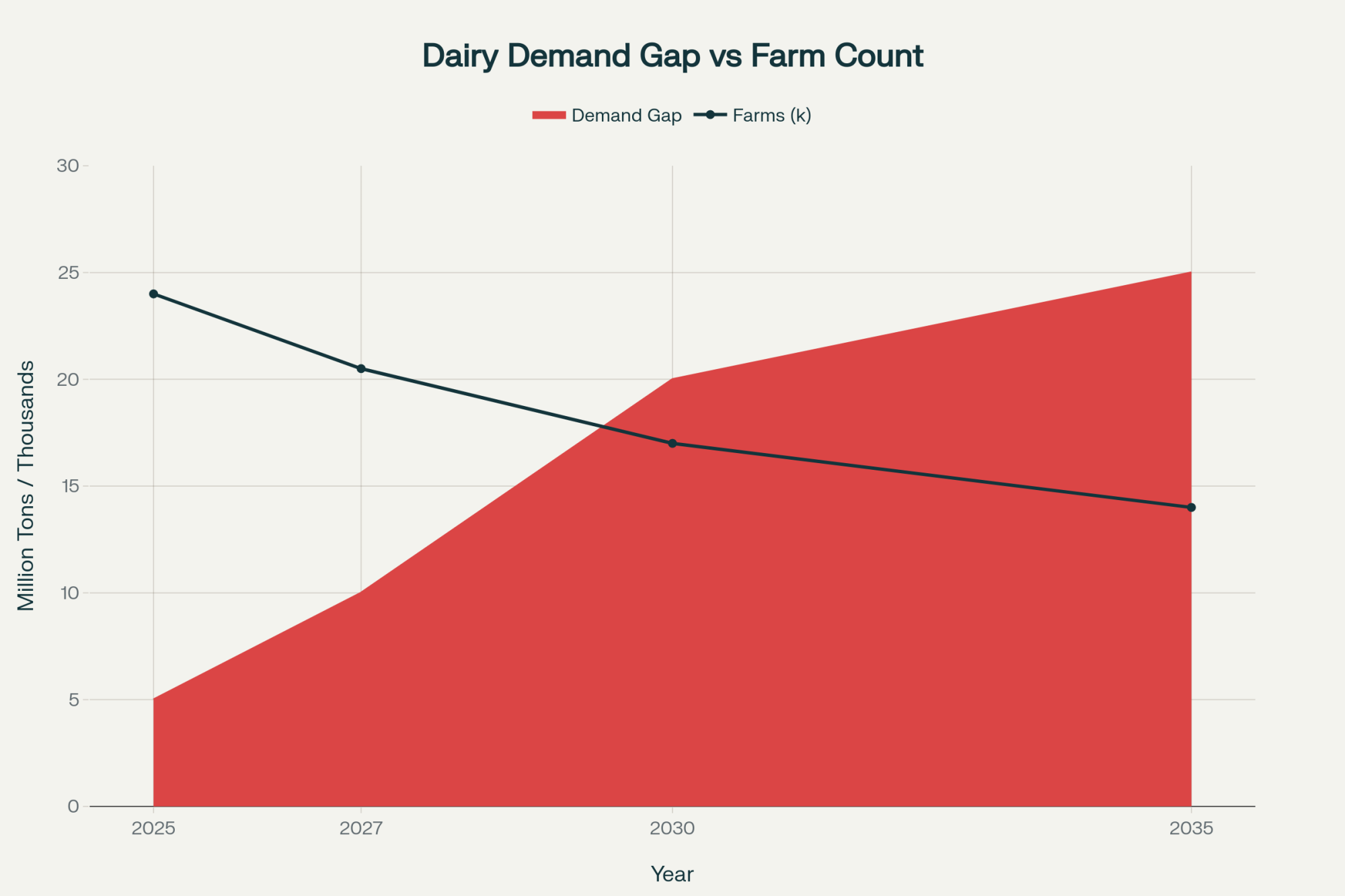

Looking ahead, several trends are becoming pretty clear. Dr. Ani Katchova at Ohio State’s Department of Agricultural, Environmental, and Development Economics thinks that by 2030, strategic bankruptcy planning might become just another standard option we discuss in farm transition planning, right alongside traditional succession strategies.

We’re likely to see continued geographic consolidation. States with high land values will keep seeing farms exit through tax-advantaged bankruptcy, with that land flowing to the remaining large operations.

Meanwhile, production’s going to keep concentrating in states like Texas and Idaho, where operations focus on efficiency rather than land equity. USDA data shows Texas already surpassed Idaho as the number three milk-producing state in 2025—they’ve grown 190% since 2001.

For young farmers trying to get started? It’s getting tougher. Iowa State’s Beginning Farmer Center reports that the traditional path—building wealth through dairy excellence over 20-30 years—is becoming nearly impossible in high-land-value regions.

Practical Thoughts for Producers

If you’re weighing your options, here’s what I’d suggest thinking about.

First, really understand your complete financial picture. Not just your cash flow, but your land equity position too. The Federal Reserve has some good agricultural finance calculators that can help you see how interest rate changes affect your debt service.

And honestly consider whether downsizing might actually strengthen your operation’s viability.

Get professional advice early—and I mean early, not when you’re in crisis mode. Find agricultural financial advisors who understand Chapter 12 provisions. IRS Publication 225 has farmer-specific guidance that’s worth reading regardless of what you decide.

Consider all your restructuring options:

- Traditional refinancing might work

- Maybe partial asset sales make sense

- Strategic Chapter 12 filing could be right if your situation aligns

- Or planned succession—even if it’s not to the family—might be the answer

And recognize that the landscape has fundamentally shifted. Higher interest rates have changed the game. Strategic downsizing isn’t failure—it’s adaptation. If you’ve been farming for decades and you’re ready to retire, that’s an achievement, not a defeat.

For younger farmers and those looking to expand, the playbook’s different. In regions where land values are not appreciating, excellence in milk production remains your primary path. Think about lease-based expansion models that don’t tie up all your capital in land. Look at emerging dairy regions where entry costs are still manageable.

You’ve got to plan for different wealth-building strategies now. Land appreciation might not provide what it did for previous generations. Consider diversifying income streams beyond traditional dairy production. Value-added processing, direct marketing—these might be where your opportunities are.

The Bottom Line

What we’re discovering about Chapter 12 bankruptcy reflects broader changes in American agriculture that we’re all navigating together. That provision Congress passed in 2017 to help struggling farmers? It’s evolved into something more complex—a financial planning tool that rewards strategic thinking about asset management as much as farming excellence.

Is that good or bad? Honestly, it depends on your perspective. For farmers who’ve built substantial equity over decades, Section 1232 provides a path to capture that value as they transition out. For communities, it can mean orderly succession instead of crisis liquidation.

But it also highlights some uncomfortable truths about modern dairy economics. When tax-advantaged bankruptcy can be more profitable than continuing to milk…when land ownership matters more than production efficiency…well, we’ve got to ask ourselves some fundamental questions about where the industry’s headed.

The 55% surge in Chapter 12 bankruptcies isn’t simply a crisis or a loophole. It’s farmers adapting to new economic realities with the tools available. Understanding these tools—how they work, what they mean, when they make sense—that’s going to be essential for anyone navigating dairy’s evolving landscape.

As that Wisconsin producer preparing for a strategic Chapter 12 filing told me: “I’ve milked cows for 35 years. I’m not failing—I’m choosing the smartest path forward for my family with the rules as they exist. If that means using bankruptcy court to maximize our retirement after decades of 4 a.m. milkings, I’m at peace with that decision.”

That sentiment—practical, unsentimental, focused on optimal outcomes—pretty much captures how American dairy farmers are approaching this transformation. The old stigmas about bankruptcy? They’re fading. What’s replacing them is a new pragmatism where strategic financial planning matters as much as picking the right bull for your breeding program or getting your ration formulation dialed in.

For better or worse, that’s the new reality we’re dealing with. And understanding it? That might just be the difference between thriving and merely surviving in the years ahead.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- The $228,000 Opportunity: Section 1232 transforms Chapter 12 bankruptcy into a tax-saving tool—farmers selling 200 acres can keep $1.54M versus $1.31M in traditional sales by discharging capital gains taxes as unsecured debt

- Strategic, Not Crisis: The 55% bankruptcy surge represents planned exits by farmers facing 8% interest rates and compressed margins, not business failures—these are profitable operations choosing smart transitions

- Winners and Losers: Benefits farmers 60+ with appreciated land in high-value states (Iowa: $10,200/acre); offers nothing for lease-based operations or young farmers trying to enter

- Timing Is Everything: This strategy requires filing bankruptcy BEFORE selling land—farmers should consult specialized ag attorneys early, not wait for a crisis

- Industry Transformation: This trend accelerates dairy’s shift from land-wealth to operational efficiency, with production consolidating in states like Texas, where success depends on milk per cow, not land appreciation

Editor’s Note: This article draws on interviews with dairy producers across Wisconsin, Arkansas, Iowa, Texas, Minnesota, and the Northeast conducted between September and October 2025. Some producers requested anonymity to discuss sensitive financial matters candidly.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- The Ultimate Guide to Dairy Farm Succession Planning – While the main article explores bankruptcy as a final exit strategy, this guide provides a proactive roadmap for a successful farm transition. It details strategies for communication, financial structuring, and legal planning to preserve the family legacy and business continuity.

- Decoding Dairy’s Crystal Ball: Top 5 Economic Trends Producers Must Watch – This strategic analysis dives deep into the market forces—like interest rates and input costs—driving the financial pressures mentioned in the main article. It provides critical context for anticipating market shifts and positioning your operation for long-term resilience.

- Beyond the Bulk Tank: How Value-Added Dairy Is Creating Bulletproof Businesses – For producers seeking alternatives to the land-equity model, this article reveals how to build a more resilient business through direct marketing and on-farm processing. It offers a tangible path for young farmers to build equity and insulate their profits from commodity volatility.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!