If you can’t write a $3M check tomorrow, you’re already extinct. The industry just hasn’t told you yet.

Okay, so I’m at World Dairy Expo last week—you know, wandering around trying to avoid the robot salesmen—and I run into this producer from Iowa. Guy’s been milking for thirty years; it’s a good operation, with about 300 head. And he tells me something that just… it stopped me cold.

He says, “I just spent $650,000 on robots, and I think I just financed my own funeral.”

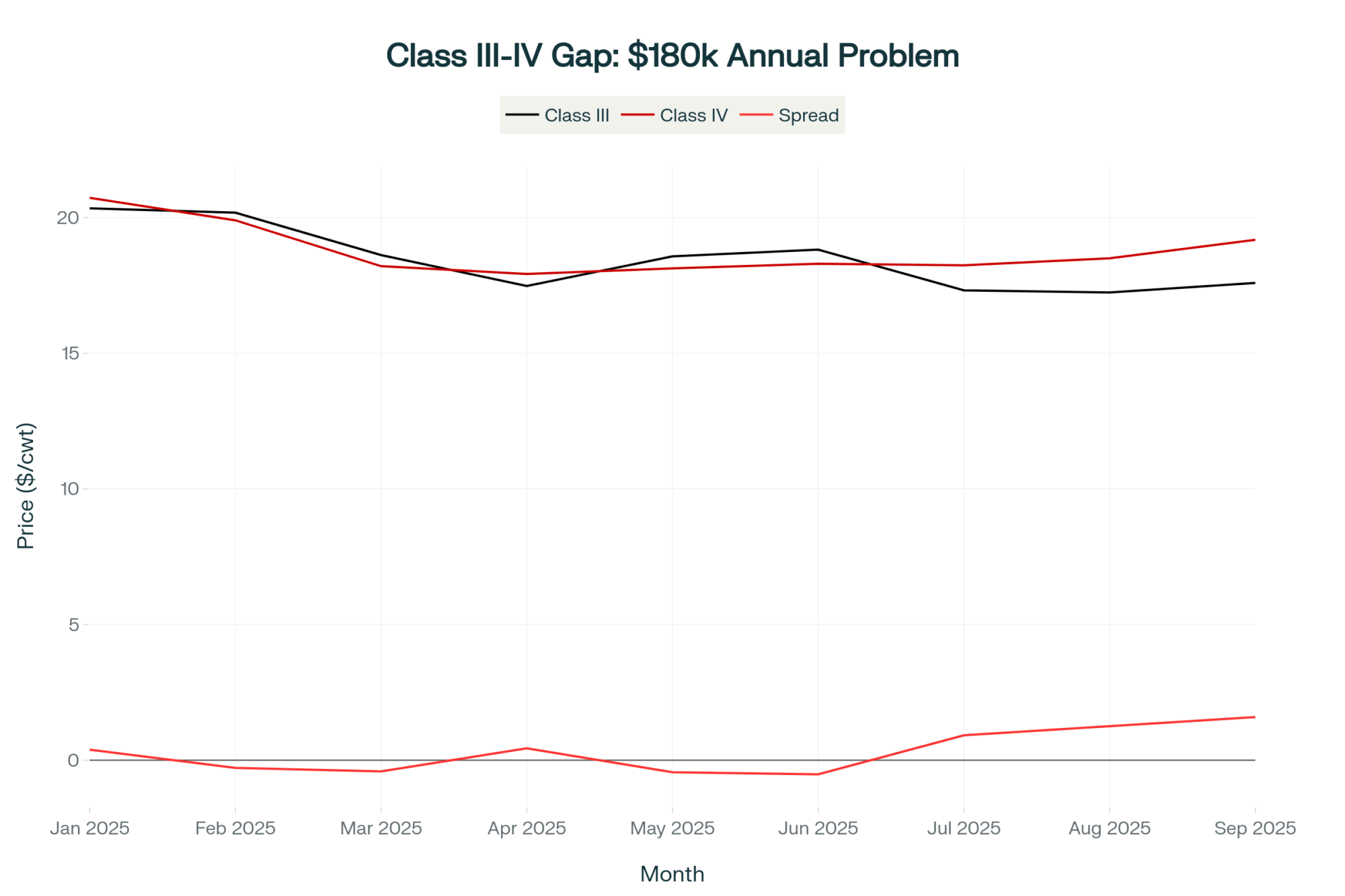

Look, we need to discuss what’s really going on here. Because while you’re trying to figure out how to make your milk check cover feed bills—corn’s what, $4.50 now if you can find a decent load?—the processors are playing a completely different game. The International Dairy Foods Association is tracking over $11 billion in new processing capacity through 2028. Eleven billion. Meanwhile, they’re quietly partnering with these lab-grown protein companies that want to make you obsolete.

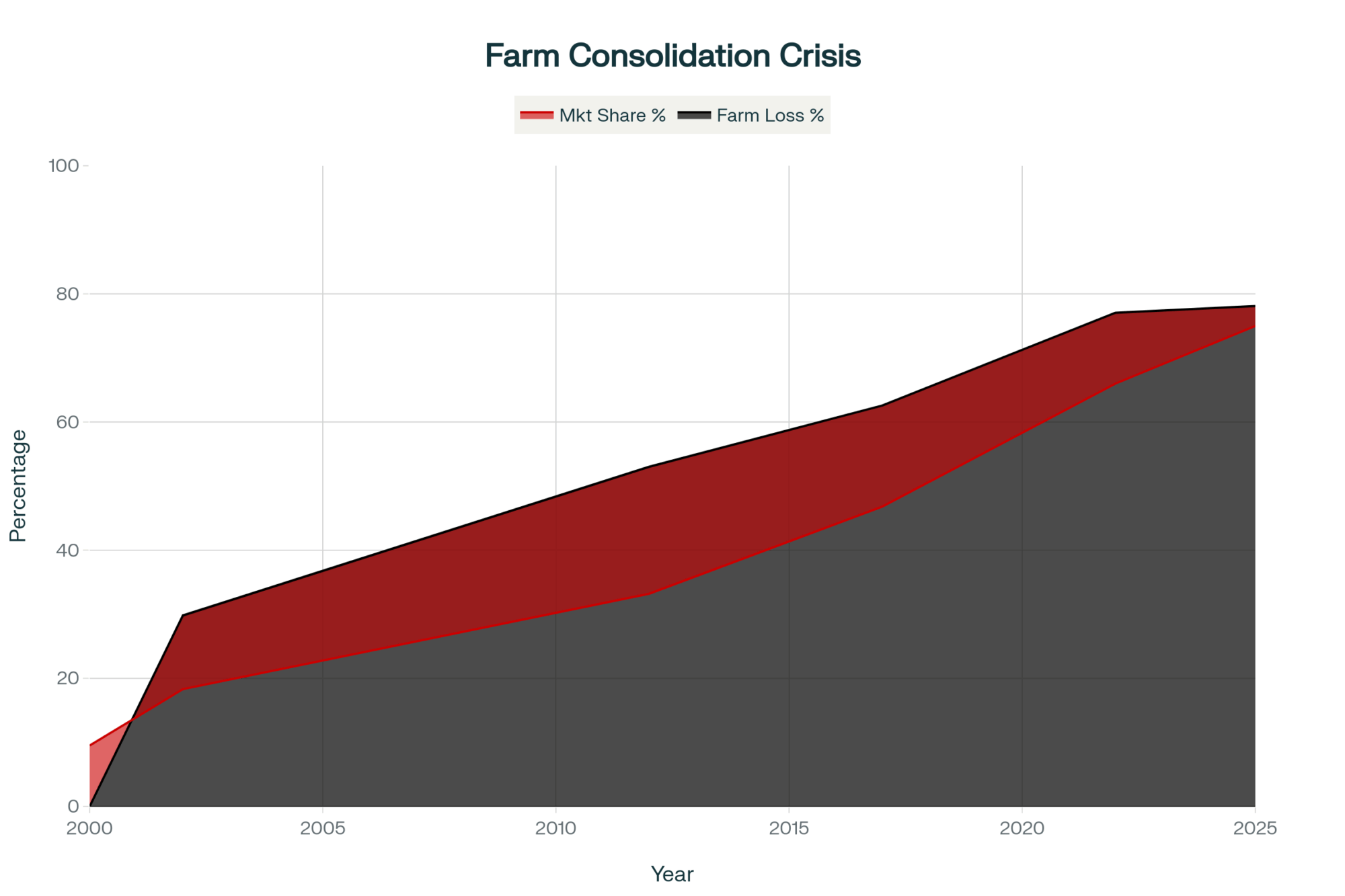

But here’s what makes me want to throw my coffee mug at the wall… North Dakota had 1,810 dairy farms when I started covering this industry back in 1987. The Census just came out—they’ve got twenty-four left. Twenty-four! I knew some of those guys who quit. Good farmers, smart operators. Didn’t matter.

(Read more “1,810 Dairy Farms to 24: Inside North Dakota’s Collapse,” this isn’t just a regional problem—it’s coming for everyone.)

And you know what? Your banker made money on every one of those exits. So did your co-op. Your processor? They just consolidated their routes and kept rolling.

So About All These New Plants Going Up…

So I’ve been following the Fairlife Webster, New York project—the one Governor Hochul showed up for at the groundbreaking back in April. They’re spending $650 million on this thing. When you read the press releases, Coca-Cola executives are talking about innovation and efficiency, and… honestly, reading between the lines, it sounds like a funeral for small dairy.

Here’s the deal—and Multiple sources familiar with the project tell me, but he doesn’t want his name associated with it—these plants are designed for one thing: mega-dairies that can deliver tank after tank of identical milk. Same butterfat, same protein, day after day. Less than 2% variation, he said.

You running 300 cows like my Iowa friend? Maybe you’re testing components once a month if you’re lucky? Brother, you’re not even on their radar.

The math is what bothers me… (hold on, let me find my notes from that Wisconsin conference)… Okay, so these plants need to run at basically full capacity to make a profit. Below 75% utilization, and they’re hemorrhaging cash. But—and here’s the kicker—milk production is actually going DOWN. The USDA says we’re off by about a quarter of a percent this year.

So what happens when you build all this capacity but there’s no milk to fill it?

Actually, I know what happens. I was talking to Mike Guenther—dairy farmer up in Nebraska, good guy, been through hell with his processor—and he told me flat out: “My infrastructure would be worth almost nothing if I tried to sell.” That’s because when there’s only one buyer in your region… well, you do the math.

The Robot Scam (And Why My Neighbor’s Wife Won’t Talk to Me Anymore)

Alright, so… robots. God, where do I even start?

My neighbor just put in a Lely system. Beautiful thing, all bells and whistles. His wife won’t talk to me anymore because I asked him—at his open house, with the Lely rep standing right there—”So what’s your exit strategy when this thing doesn’t pencil out?”

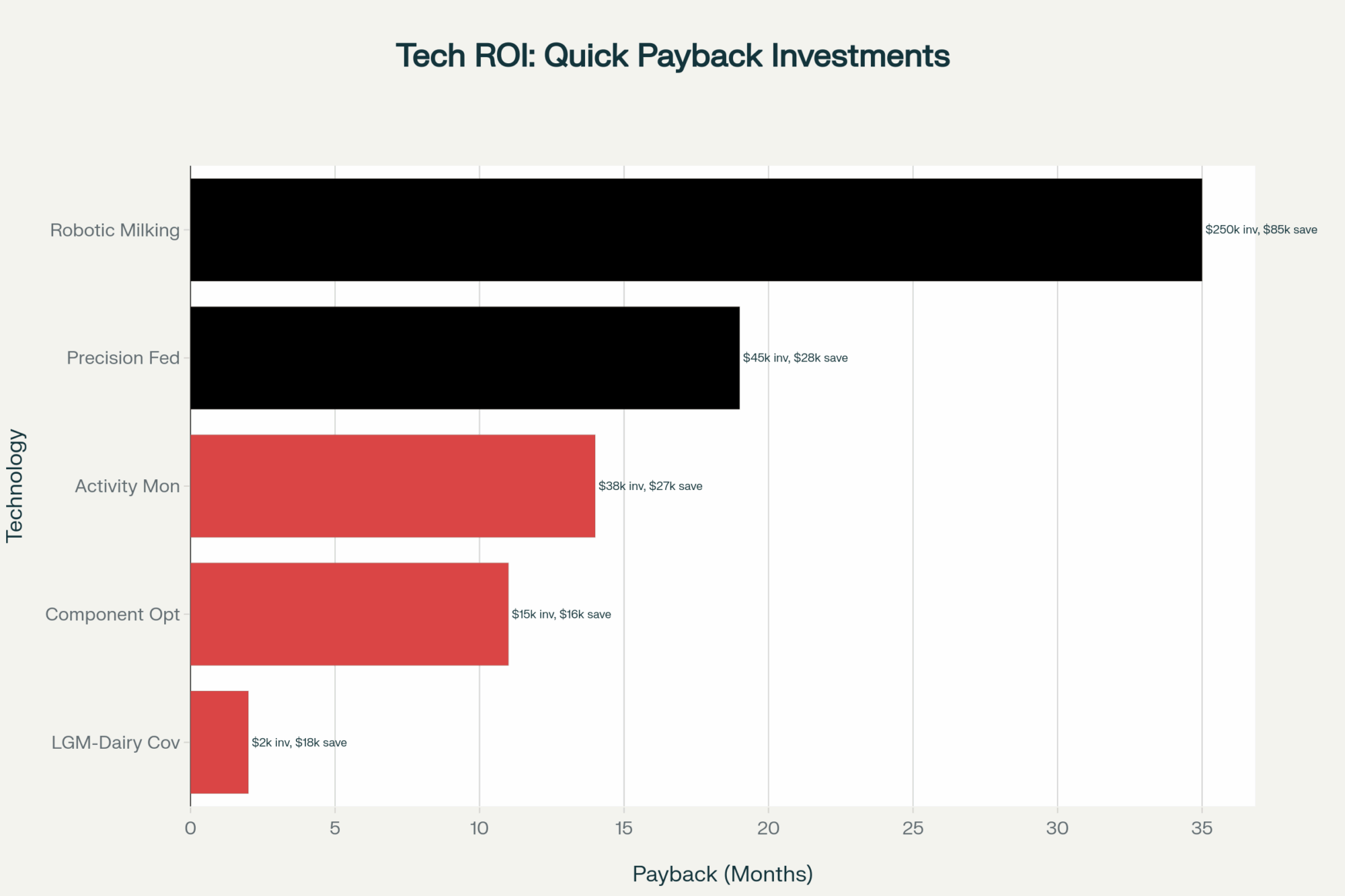

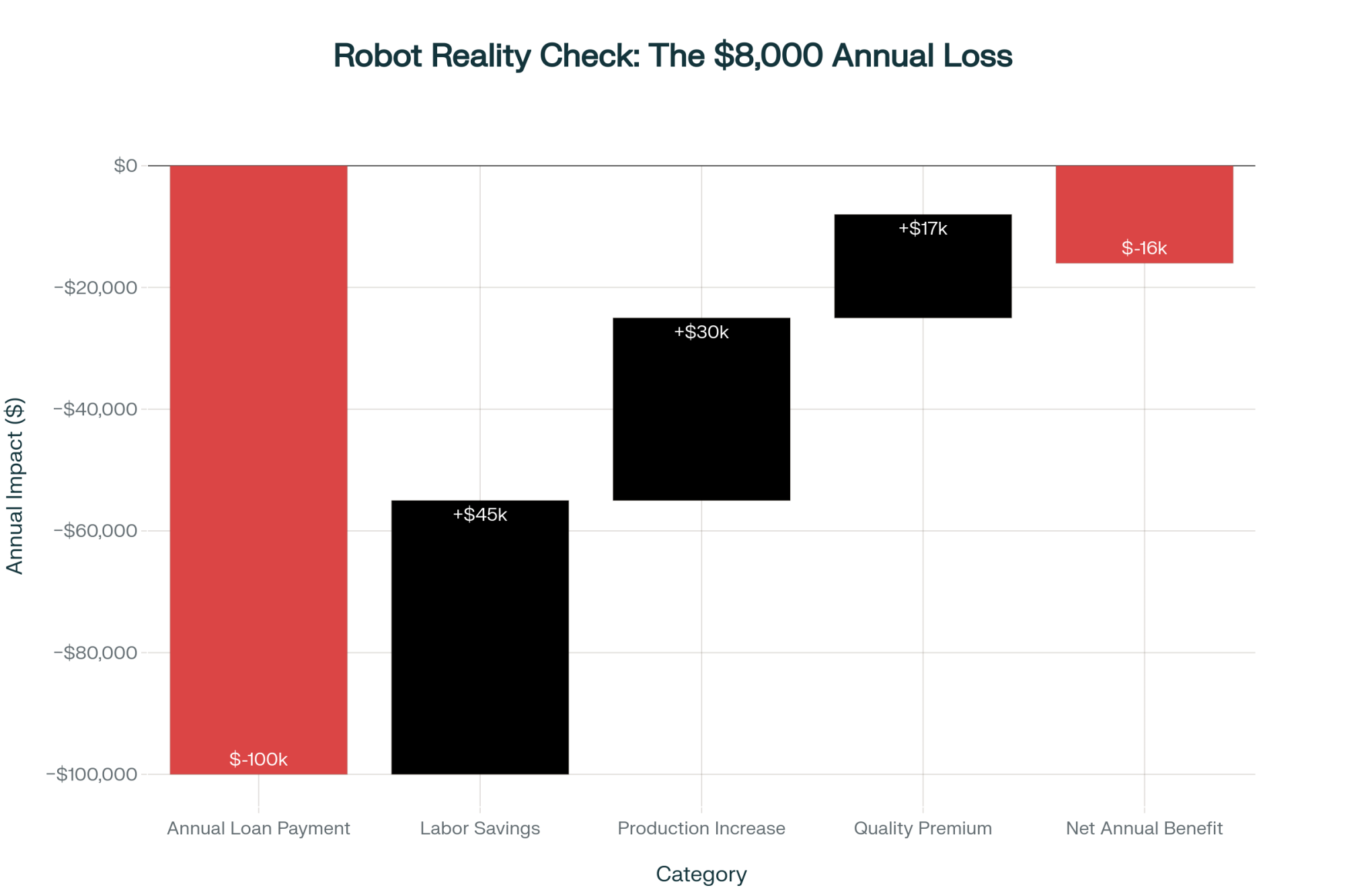

Look, I’ve seen the actual numbers from Wisconsin’s dairy center. Best case—and I mean absolute fairy-tale best case—you might save $38,000 a year on labor. Might. That’s if nothing breaks, which… have you seen the maintenance bills on these things? My cousin in Minnesota; his robot has been down three times since August. Three times!

Your components might improve—the sales team loves to talk about this—maybe even get you another twenty thousand if you’re shipping to someone who actually pays quality premiums. (Good luck finding that unicorn this time of year.) Production bump? Sure, maybe 8%, call it fifty thousand in a good year.

But that loan payment? You’re looking at damn near a hundred grand annually on $650,000. And that’s if you got decent terms, which… with milk prices where they are?

The thing that really gets me—and I was just discussing this with some folks at Penn State—is that the 2,000-cow operations don’t need robots to achieve these efficiencies. They get them automatically through scale. You’re literally paying three-quarters of a million dollars to achieve what the big guys get for free.

But hey, at least the robot dealer got his commission, right?

The Organic Mess (Or: How to Lose Money Even Faster)

Speaking of bad decisions… let me tell you about organic.

I was at a meeting in Vermont last month—beautiful country up there, with the leaves just starting to turn—and Ed Maltby from the Northeast Organic Group got up and said something that made half the room go silent: “We’ve been underwater on cost of production since 2018.”

Since 2018! Can you believe that?

Here’s how the organic trap works, and I’ve watched too many good farmers fall for this… You decide to transition, right? Takes three years. Three years of paying organic feed prices—last time I checked, depending on your region, we’re talking something like three hundred, three-fifty a ton for corn—while still getting paid conventional prices for your milk.

This producer I know in Wisconsin—she’s a smart woman who really knows her stuff—just finished her transition last spring. Guess what? Organic Valley’s not taking new producers. Horizon? They told her maybe next year, if she can guarantee 30,000 pounds daily. She’s doing 18,000.

The UK recently reported (I was reading this on the plane back from California) that it lost 7% of its organic herds in one year. One year! The USDA’s tracking similar numbers here—we’ve lost about a fifth of our organic dairies in the past five years.

And it’s not because they can’t produce organic milk. They can. It’s because nobody will buy it at a price that covers costs. The processors cherry-pick who they want, when they want.

Meanwhile, the certification consultants received their fees—ten to fifty thousand dollars, depending on the operation. The feed companies locked you into those premium contracts. Everyone made money except the farmer. Sound familiar?

Your Co-op Isn’t Your Friend Anymore

This is gonna piss some people off, but… whatever. It needs saying.

You know that DFA antitrust case? The one they settled for $50 million back in 2015? (Dean Foods kicked in another $30 million, by the way.) I was covering those hearings in Tennessee—what a circus that was. The stuff that came out about market manipulation…

But here’s what really matters: The practices they were accused of? That’s basically standard operating procedure now. Your average milk supply contract—and I’ve read dozens of these—requires 12 to 24 months’ notice if you want to leave. Some have these “loyalty bonuses” that turn into penalties if you exit.

I was talking to this farmer in Ohio last week… he wanted to switch processors, found someone offering fifty cents more per hundredweight. You know what his co-op told him? The additional hauling would eat up seventy cents. Take it or leave it.

Look at your co-op board sometime. Really look at them. How many are running mega-operations? A colleague who covers DFA meetings in the Midwest told me that at one regional meeting in Kansas, eight of twelve board members were shipping over 50,000 pounds daily. You think they care about the guy milking 150 cows?

They’re not representing you anymore. They’re managing your decline while protecting their own operations.

The Precision Fermentation Thing Nobody Wants to Talk About

Okay, this is where it gets really interesting… or terrifying, depending on how you look at it.

So, Leprino Foods—and if you don’t know, they basically own the pizza cheese market, with a market share of around 85%—announced on July 16, 2024, that they’re partnering with a Dutch company, Fooditive, to produce lab-grown casein.

Not researching it. Not thinking about it. Actually producing it. Their president, Mike Durkin, said they’re planning hundreds of thousands of tons. Starting next year.

Now, I was just reading the Good Food Institute’s latest report (fascinating stuff if you can’t sleep)… these lab proteins still cost way more than real dairy. We’re talking two to five times more expensive. But—and this is the part that should scare you—costs are dropping fast. The projections indicate that they will capture approximately 15% of the high-value protein market by 2030.

Why does that matter? Because those specialty proteins, those functional ingredients… that’s what’s been subsidizing your commodity milk price all these years. When that goes away…

Industry analysts are saying, but they work for one of the big dairy investment firms—and they told me straight up: “Traditional dairy will keep the volume markets, the cheap commodity stuff. But is everything profitable? That’s going to fermentation.”

The processors aren’t stupid. They see this coming. That’s why they’re building $11 billion in infrastructure for maybe 300 mega-farms while letting everyone else twist in the wind.

Why Everyone Needs You to Keep Losing Money

You want to know something that’ll make you sick?

Cornell’s farm management people did this study—I actually know Wayne Knoblauch, good guy, tells it straight—and they found that if you’re living off equity (basically burning through your farm’s value to cover losses), every year you wait to exit costs you fifty to a hundred grand in destroyed wealth.

But nobody’s gonna tell you to quit. Know why?

Your lender needs active loans on their books. I was talking to a Farm Credit loan officer at a bar in Madison—after a few beers, he admitted it—they’d rather restructure a bad loan five times than have a foreclosure on their report.

Your processor? They need volume. Lose half of their suppliers, and their entire system falls apart. I’ve seen the efficiency studies from Wisconsin—it’s brutal what happens to their costs when volume drops.

Extension can’t tell you to quit either. Too political. I know extension agents who’ve been pulled aside and told to focus on “farm viability strategies” not “transition planning.” Can you believe that?

What’s Really Coming (And It Ain’t Pretty)

People keep asking me about the future of dairy. There are three possible scenarios, or something.

There’s not. There’s one. And we’re already most of the way there.

The USDA’s latest numbers, which I just pulled yesterday, show that operations with more than 1,000 cows control about two-thirds of production now. Back in 2017? It was barely over half. The Census shows farms with 2,500 or more cows went from 714 to 834.

(Read more: “Pick Your Lane or Perish: The 18-Month Ultimatum”—the middle is disappearing.)

We’re not “heading toward” consolidation. We’re in year 15 of a 25-year comprehensive restructuring. By 2030? The International Farm Comparison Network projects we’re down to maybe 18,000 total dairy farms. By 2035? We’re looking at something like the poultry industry—vertical integration, contract production, three or four companies controlling everything.

You’ve got maybe two years to figure out where you fit in this picture. After that? The decision gets made for you.

The Bird Flu Wild Card That Has Everyone Spooked

But just as the mega-dairies feel invincible, an entirely new risk has emerged—a biological one that turns their efficiency into a vulnerability. And then there’s this H5N1 thing…

Nobody wants to discuss this at industry meetings, but I was just reviewing USDA’s latest report—we now have infected herds in 17 states. California alone had 475 confirmed cases as of December, according to that Congressional Research Service report. Wisconsin’s been testing thousands of milk samples since April.

Here’s what scares me: CDC research indicates that this virus can spread through milking equipment. You know what that means for these 2,500-cow operations? They’re basically petri dishes. One infected cow, and it spreads to the whole herd within days.

Meanwhile, that 50-cow farm everyone says isn’t viable? Suddenly, their isolation looks pretty smart, doesn’t it?

I was talking to a veterinarian in Arizona—they’re modeling this stuff now—and she thinks if this escalates… I mean, imagine consumers finding out there’s viral material in milk. Even if pasteurization makes it safe, which it does, the demand hit could be catastrophic.

But hey, don’t count on bird flu to save small dairy. That’s not a business plan.

The Exit Math Nobody Will Show You

Alright, let’s talk about getting out. Because for a lot of you, that’s the smartest move, and I’m tired of pretending otherwise.

Wisconsin’s farm center won’t publish this directly—too controversial—but if you read between the lines… Say you’re running 200 cows and losing $75,000 a year after accounting for family living expenses. Pretty common scenario these days.

Keep going for five years? You burn through $375,000 in equity. By the time you finally quit, you’re down to maybe $1.1 million in assets. At 4% returns—if you’re lucky—that’s $45,000 a year in retirement.

But if you exit now with $1.5 million still intact? Same 4% gets you $60,000. That’s fifteen grand more every year for the rest of your life.

Signs You Should Exit Now

- Losing more than $50,000 annually after family living expenses

- Over 55 with no succession plan

- Debt-to-asset ratio above 60%

- Single processor within 50 miles

- Can’t afford $500,000 in upgrades

- Working 80+ hours weekly with no vacation in 3 years

I know appraisers who’ll tell you—off the record—selling separately gets you way more than selling as a complete dairy. Land to crop farmers, cows to other dairies, equipment at auction. You might get 30-50% more that way. Stage it over 18-24 months for tax purposes, and watch the Class III futures for timing.

But your banker won’t run these numbers for you. Your co-op sure as hell won’t. And extension? They can’t even have this conversation without risking their funding.

The Bottom Line (Or: What I’d Tell My Own Son)

Look… I’ve been covering this industry for almost forty years. I’ve seen good farmers, smart people, hardworking families get absolutely destroyed by forces beyond their control.

The consolidation we’re seeing? It’s 70% done already. The infrastructure being built isn’t for family farms—it’s for their replacement. Every “solution” they’re pushing—robots, organic, value-added—it’s designed to extract what value you have left before you’re forced out anyway.

If you’re under 500 cows without a clear path to premium markets? You need millions to scale up (good luck with that), or years of off-farm income to transition to specialty markets (also good luck), or… you need to think about exiting while you still have something to exit with.

If you’re my age—late 50s, early 60s—without someone to take over? Every day you wait is lighting money on fire. Simple as that.

Thinking about robots? That $650,000 might buy you five to seven years of life. Then what? If you don’t have a ten-year plan after the robot, you’re just financing your own extinction with interest.

The hardest truth—and I’ve looked at enough financial data to feel pretty confident about this—probably 60-70% of current dairy farmers would be better off financially by selling tomorrow. Not next year. Not after corn harvest. Tomorrow.

But nobody in this industry will tell you that. They need you operating, even at a loss. Your losses keep their system running.

You know what you are now? You’re not a dairy farmer. You’re an unwitting participant in your own wealth extraction. The only question is whether you’ll recognize it before it’s too late.

I’m not sure… maybe I’m wrong. Maybe there’s some miracle coming that’ll save small dairy. But I was at an auction last month—good family, who had farmed that land for four generations—and watching them sell off everything piece by piece… The old man was trying not to cry, and his son just looked angry…

That’s not how this is supposed to end. But for most of us, that’s exactly how it will end unless we face reality now.

Look, make your own decision. But make it with your eyes open. Because in about 24 months, maybe less, the decision gets made for you.

And trust me—you want to be the one making that call, not having it forced on you.

Share this with every dairy farmer you know. They deserve the truth.

The decision is coming. The only power you have left is to make it yourself.

Key Takeaways:

- Your 24-Month Countdown Starts Now: $11B in processor overcapacity will crash prices by 2027—only 300 mega-farms survive the engineered consolidation

- The $375,000 Decision: Exit today = $60k/year retirement. Bleed equity five more years = $45k/year. Your banker won’t show you this math

- Robot Truth: You pay $100k annually to save $38k in labor—meanwhile, 2,000-cow operations get same efficiency free through scale

- The Betrayal Is Complete: Processors partnered with lab-protein companies (Leprino/Fooditive, July 2024) while selling you “growth solutions”

- Three Options Left: Find $3M to scale past 1,000 cows, secure premium markets with off-farm income, or exit while assets have value

Executive Summary:

An Iowa dairy farmer told me last week: “I spent $650,000 on robots and just financed my own funeral.” He’s absolutely right—and the betrayal runs deeper than you know. Processors are investing $11 billion in infrastructure designed exclusively for 300 mega-dairies while partnering with lab-protein companies (Leprino/Fooditive, July 2024) to replace traditional dairy’s profitable products. The math reveals everything: farmers losing $75,000 annually would save $375,000 by exiting today versus operating for five more years, yet every institution—your bank, co-op, processor—needs you to bleed equity to maintain their economics. With 24 months until processing overcapacity crashes milk prices and forces mass consolidation, you face three options: find $3 million to scale beyond 1,000 cows, secure premium markets with off-farm income support, or exit strategically while assets retain value. For 60-70% of current operations, immediate exit preserves the most family wealth—but nobody will tell you this because your losses subsidize their entire business model.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Learn More:

- Dairy Robots: Are They Right for Your Farm? – This guide provides the tactical, detailed cost-benefit analysisthe main article avoids. It demonstrates how to perform objective due diligence, revealing the precise operational metrics needed to achieve true profitability and overcome the negative equity trap of automation.

- Fonterra’s $500M Biotech Gamble: Blueprint for Future-Proofing Dairy or Expensive Science Experiment? – Understand the strategic, defensive moves major co-ops are making, from methane reduction to biotech partnerships. This article reveals how leading global players are systematically restructuring to maintain a competitive advantage against the very threats detailed in the main piece.

- The Lab-Protein Revolution: Why Every Dairy Producer Needs to Understand This $840 Million Bet Against Traditional Whey – Dive deeper into the technology and economics of precision fermentation. Learn which high-value protein markets are under immediate attack, giving you the specific intelligence needed to proactively diversify your milk composition strategy before the market collapses.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!