Stop milk fever before it starts! Discover how negative DCAD diets boost calcium, slash transition disorders, and add $640+/cow in milk profits.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Negative DCAD diets (-8 to -12 meq/100g DM) remain dairy’s gold standard for transition cows, preventing hypocalcemia by priming calcium mobilization, boosting milk yield, and reducing metabolic disorders. Backed by decades of research, this strategy improves multiparous cow health and profitability but harms first-calf heifers’ reproduction. Key implementation steps include urine pH monitoring (6.0-6.8 for Holsteins), selective use of commercial anion supplements, and avoiding over-acidification. Modern refinements like neutral DCAD diets show promise but require further validation. With proper execution, farms report 0+/cow savings from avoided milk fever and 1,800-3,200 lbs increased lactation yields.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- Target -8 to -12 meq DCAD for 21 days pre-calving to prevent milk fever and boost calcium availability

- Urine pH 6.0-6.8 (Holsteins) confirms effectiveness – extreme acidification reduces intake

- Exclude first-lactation heifers – negative DCAD impairs their reproduction

- $640+/cow profit potential from higher milk yields and disease prevention

- Neutral DCAD (0 ±30 meq) emerging as a palatable alternative with 87% milk fever reduction

Feeding negative Dietary Cation-Anion Difference (DCAD) diets to transition dairy cows has stood the test of time, with hundreds of research studies confirming its effectiveness in preventing metabolic disorders and improving performance. This scientifically validated nutritional strategy significantly reduces the risk of hypocalcemia (milk fever) and enhances overall migration to cow health. This report examines the mechanisms, benefits, implementation strategies, and latest research on negative DCAD diets for dairy producers seeking to optimize transition cow management.

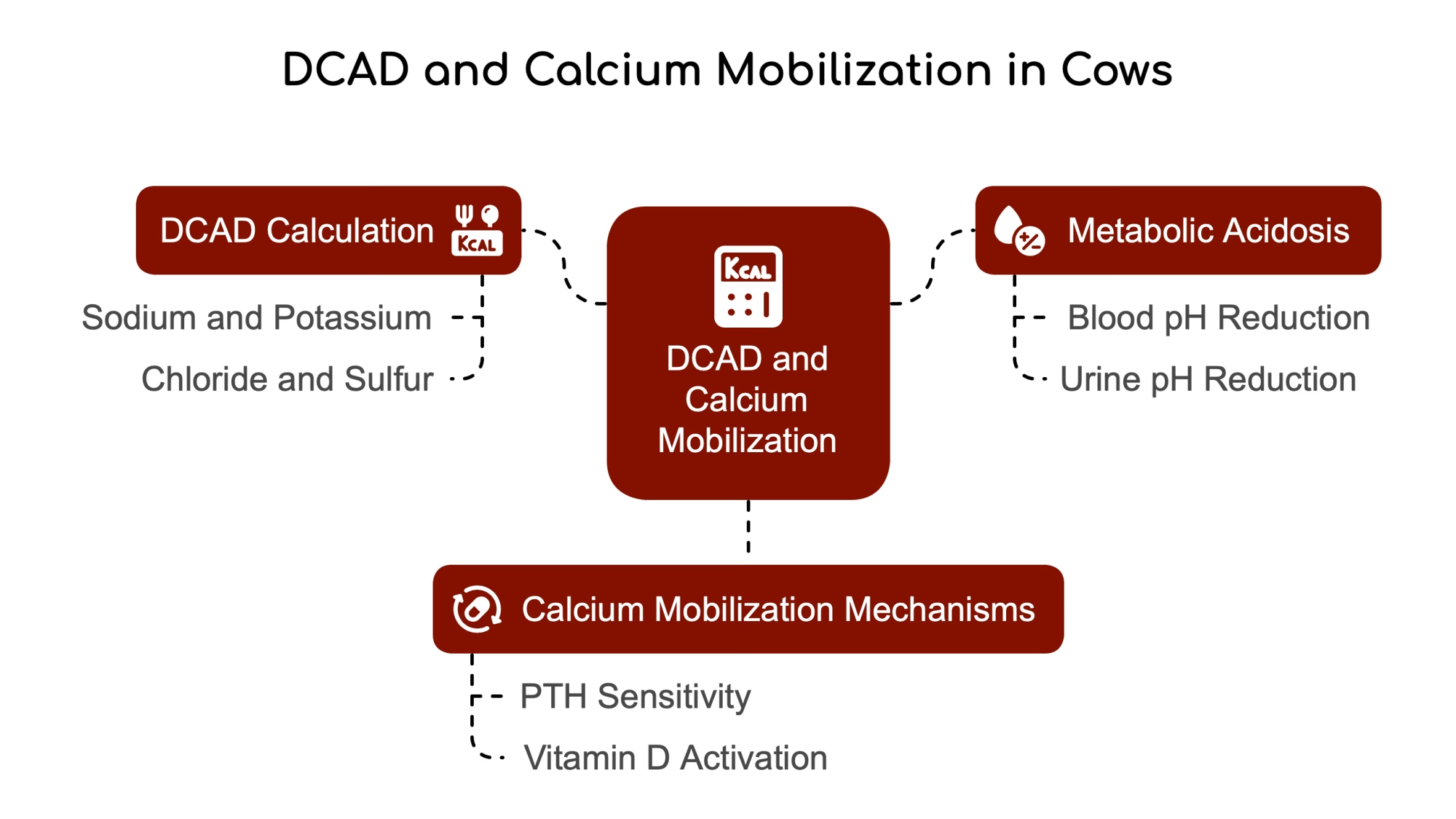

Why DCAD Works: The Science Behind Calcium Mobilization

DCAD represents the diet’s balance between positively charged cations (primarily sodium and potassium) and negatively charged anions (chloride and sulfur). The most used formula to calculate DCAD is DCAD (meq) = (Na + K) – (Cl + S). A negative DCAD diet contains proportionately more chloride and sulfur in relation to potassium and sodium, thus lowering the dietary cation-anion difference value.

When cows consume a negative DCAD diet, they enter a state of compensated metabolic acidosis, which results in a slight reduction in blood pH and a significant reduction in urine pH. This subtle change in blood pH plays a crucial role in calcium metabolism. The slight acidification increases the sensitivity of tissues to parathyroid hormone (PTH), which helps mobilize calcium from bone reserves and enhances calcium absorption in the intestine.

This metabolic adaptation is significant during the transition period when calcium demands skyrocket. When a cow begins lactation, her calcium requirement suddenly increases dramatically as calcium moves from the bloodstream into colostrum and milk. Proper metabolic preparation can lead to a dangerous drop in blood calcium levels. Negative DCAD diets essentially “prime” the cow’s calcium metabolism system to respond more efficiently to this challenge.

The Calcium Mobilization Pathway: How DCAD Unlocks Bone Reserves

The biological pathways involved in calcium mobilization are complex but well-understood. When blood pH is slightly reduced through negative DCAD feeding, PTH receptors become more responsive. This enhanced sensitivity triggers two key calcium-regulating mechanisms: first, PTH has a direct effect on bone, stimulating the breakdown of bone tissue and releasing stored calcium into the bloodstream; second, PTH stimulates the kidneys to produce more active vitamin D, which in turn increases calcium absorption from the digestive tract.

3 Major Benefits of Negative DCAD Diets That Boost Your Bottom Line

The benefits of feeding negative DCAD diets during the transition period extend far beyond just preventing clinical milk fever. Research has consistently demonstrated multiple advantages for dairy cows and farm productivity.

1. Slash Hypocalcemia Rates: Stop Milk Fever Before It Starts

Hypocalcemia occurs in both clinical (milk fever) and subclinical forms. While clinical cases are obvious when cows go down and cannot stand, subclinical hypocalcemia affects a much more significant percentage of the herd, often 50% of mature dairy cows and 25% of first-calf heifers. These cows appear normal but have reduced blood calcium levels that impair muscle function throughout the body, including the digestive tract and uterus.

A meta-analysis of controlled experiments showed that feeding a negative versus positive DCAD diet reduced the relative risk of developing milk fever to between 0.19 and 0.35. This represents an impressive 65-81% reduction in milk fever risk simply through dietary management. Research has consistently shown that negative DCAD diets can eliminate clinical hypocalcemia and drastically reduce the incidence of subclinical hypocalcemia.

2. Boost Milk Production: More Milk in the Tank

Beyond disease prevention, negative DCAD diets have been shown to enhance lactation performance. A comprehensive meta-analysis found that lowering DCAD increased ionized calcium in blood before and at calving. This improved calcium status supports higher milk production in early lactation.

Research consistently shows that properly implemented negative DCAD programs lead to higher milk production, particularly in second lactation and older cows.

3. Reduce Transition Disorders: Healthier Cows, Fewer Vet Bills

The benefits extend to other transition disorders as well. Studies show a decreased incidence of retained placentas, metritis, displaced abomasums, and improved reproductive performance in cows fed negative DCAD diets. This is partly because calcium is necessary for proper muscle contraction throughout the body, including the uterus and digestive tract. When calcium levels are maintained, these systems function more effectively.

How to Implement a Successful DCAD Program on Your Dairy

Implementing a negative DCAD program requires careful attention to diet formulation and monitoring. Research has identified optimal ranges and practical approaches to achieve the desired effects.

The Perfect DCAD Range: Don’t Go Too Low

The scientific consensus points to an optimal negative DCAD range of -8 to -12 meq per 100 grams of dry matter for transition cows. This level can produce the desired metabolic effects without excessive acidification or decreased feed intake.

Interestingly, research shows that pushing DCAD levels beyond -12 does not provide additional benefits and may be counterproductive. Studies found that reducing the level of negative DCAD too far reduced prepartum dry matter intake and induced a more exacerbated metabolic acidosis. This demonstrates that more is not necessarily better regarding DCAD manipulation.

Table 1: DCAD Implementation Guidelines

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Key Considerations |

| Prepartum DCAD | -8 to -12 meq/100g DM | Avoid < -15 meq for intake |

| Postpartum DCAD | +35 to +45 meq/100g DM | Supports lactation |

| Urine pH (Holstein) | 6.0-6.8 | Test 3+ days after initiation |

| Urine pH (Jersey) | 5.5-6.0 | Breed-specific metabolism |

| Feeding Duration | 21-42 days prepartum | Longer periods are still effective |

4 Steps to Implement DCAD Successfully on Your Farm

Successful implementation of a negative DCAD program requires several key steps:

- Analyze feed ingredients thoroughly: Conduct chemical analysis to know the exact DCAD levels of your feed ingredients and forages. This is crucial because natural variation in mineral content, especially in forages, can significantly impact the final DCAD value.

- Minimize dietary potassium and sodium: Decrease these cations as much as possible in the transition diet. This often means avoiding or limiting high-potassium forages like certain alfalfa hays.

- Add appropriate anionic supplements: Adjust DCAD to the target negative range by adding a palatable anion source to the ration. While raw anionic salts were used in early research, many commercial products now offer improved palatability and consistency.

- Ensure adequate mineral balance: Formulate magnesium above 0.40% of total dry matter and provide sufficient calcium and phosphorus. Research has demonstrated that when more than 180 grams of dietary calcium are fed with a fully acidogenic diet, cows become more resistant to decreases in serum calcium concentrations.

Monitoring Success: The Urine pH Test You Need to Master

Urine pH testing is the simplest and most effective way to monitor whether a negative DCAD diet works appropriately. This non-invasive, low-cost method provides immediate feedback on the cow’s metabolic acid-base status.

Target pH Ranges: Not Too High, Not Too Low

For Holstein cows, the target urine pH range is typically 6.0-6.5, while Jersey cows generally require a slightly lower range of 5.5-6.0 due to breed differences in acid-base metabolism. Some sources recommend a broader range of 6.0-6.8 for all cows. If urine pH falls outside the recommended range, adjustments to the diet or feeding management are needed.

Recent research indicates that urine pH readings below 6.0 may not be reliable indicators of metabolic acid-base status. Once urine pH drops below 6.3, the kidneys change how they remove hydrogen ions from the blood, making urine pH a less reliable indicator of how close the cow is to uncompensated metabolic acidosis.

Simple Testing Protocol: No Need to Check Every Cow

After introducing a negative DCAD diet, wait at least three days before testing urine pH to allow the metabolic effects to develop. Rather than testing every cow daily, select a representative sample (approximately 10%) of cows on the diet for several days. Testing should be done consistently relative to feeding, as there can be diurnal variations in urine pH.

It’s important to remember that the goal is not to achieve the lowest possible urine pH. Instead, urine pH indicates that the negative DCAD diet is achieving the desired metabolic effect. There’s no benefit to extremely low urine pH values, which may indicate excessive acidification.

Timing Matters: When to Start and Stop DCAD Feeding

The timing and duration of negative DCAD feeding are essential factors in maximizing its benefits while managing costs and logistics.

Optimal Feeding Window: The 3-Week Sweet Spot

The standard recommendation is to feed negative DCAD diets during the last three weeks before expected calving. This timeframe allows sufficient opportunity for the diet to influence calcium metabolism before the calcium challenge of lactation begins.

Some research indicates that feeding a negative DCAD diet for more extended periods, up to 42 days before calving, can also be practical and doesn’t appear to cause problems. This flexibility can benefit farms with limited ability to move cows between groups frequently.

Group Housing Strategies: Making DCAD Work in Your Barn

If pen moves or grouping strategies don’t allow a separate transition group to be formed 21 days prepartum, farms can still benefit from negative DCAD feeding. Research suggests that starting negative DCAD diets earlier in the dry period can yield health and production benefits like the standard three-week protocol.

However, it’s important to note that DCAD manipulation is not recommended for lactating cows, where a positive DCAD diet is beneficial for milk production. Research suggests a negative DCAD in the prepartum stage and a positive DCAD in the postpartum stage for optimal milk production efficiency and minimal metabolic disorders.

Critical Considerations: The Latest Research Findings You Need to Know

While negative DCAD diets have proven highly effective, there are some important considerations and potential limitations to keep in mind.

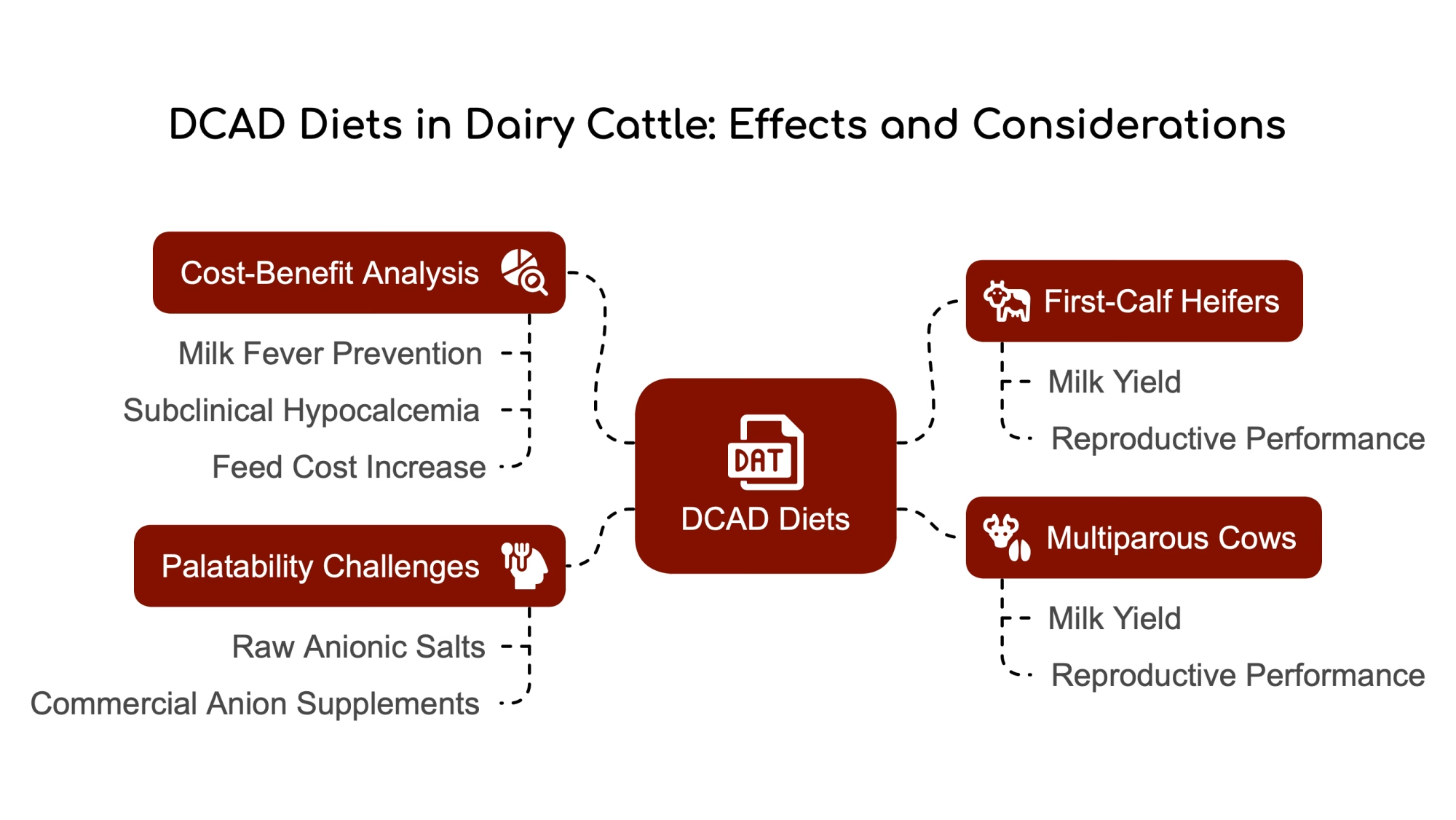

First-Calf Heifers: Why DCAD May Hurt, Not Help

Recent research has revealed that nulliparous cows (first-calf heifers) respond differently to negative DCAD diets than multiparous cows. Studies have found that reducing DCAD improved milk, fat-corrected milk, fat, and protein yields in multiparous cows; however, in nulliparous cows, reducing DCAD either did not affect milk and protein yields or reduced fat-corrected milk and fat yields.

Research has found that the reproductive performance of first-lactation heifers was impaired when fed negative DCAD diets, in contrast to their older herd counterparts. This research suggests that different DCAD recommendations may be needed for first-calf heifers, and negative DCAD diets are not recommended for this group.

Table 2: Parity-Specific Responses to Negative DCAD

| Outcome | Multiparous Cows | Nulliparous Cows |

| Milk Yield Change | +1.7-3.2 kg/d | No improvement/Reduction |

| Reproductive Performance | Improved | Impaired |

| Recommended DCAD | -8 to -12 meq/100g DM | Neutral/Positive DCAD |

| Metabolic Benefit | Strong calcium mobilization | Minimal benefit |

Palatability Challenges: Keeping Feed Intake Strong

One of the main drawbacks of traditional negative DCAD programs is palatability issues with raw anionic salts, which can reduce feed intake. Decreased prepartum feed intake is an expected response when feeding negative DCAD diets due to induced metabolic acidosis. However, modern commercial anion supplements often have improved palatability compared to raw anionic salts.

Research has clarified that the depression in feed intake is not necessarily related to the inclusion of acidogenic products but is caused by the metabolic acidosis induced by the acidogenic diet.

The DCAD Cost-Benefit Analysis: Is It Worth It? (Spoiler: Yes!)

Decreasing the ration DCAD to achieve very low urine pH values adds unnecessary cost without additional benefits. When formulating from a base diet of +18 to a negative DCAD of -8, there is a cost associated with adding anionic supplements. Pushing beyond necessary levels (e.g., from -10 to -14) adds cost with no added benefit.

Given that first-lactation heifers may not benefit from negative DCAD diets and could experience reproductive impairment, selective use of negative DCAD diets only for multiparous cows could provide significant cost savings.

Table 3: Economic Impact of DCAD Implementation

| Factor | Typical Impact | Economic Value |

| Milk Fever Prevention | 65-81% reduction | $300/case avoided |

| Subclinical Hypocalcemia | 50% reduction | $125/cow in lost production |

| Feed Cost Increase | $0.65/cow/day | – |

| Milk Yield Increase | 1,800-3,200 lbs/lactation | $360-640/cow (@$0.20/lb) |

| Reproductive Efficiency | 15% improvement | $150/cow in reduced losses |

Cutting-Edge DCAD Research: What’s New in Transition Cow Nutrition

Research on DCAD continues to evolve, with scientists exploring refinements and alternatives to traditional approaches.

Moderate vs. Extreme Acidification: Finding the Sweet Spot

Recent research has focused on moderate acidification (pH 6.0-7.0) and extreme acidification (pH below 6.0). The evidence suggests that moderate acidification provides the benefits of improved calcium metabolism without the risks of uncompensated metabolic acidosis that can occur with extreme acidification.

Studies have shown that regardless of the blood calcium threshold used to establish hypocalcemia, the incidence of hypocalcemia and related health problems was not decreased by making cows extremely acidotic.

Neutral DCAD: A Promising Alternative?

While negative DCAD diets remain the gold standard, some researchers are investigating whether a neutral DCAD (0 ± 30 mEq/kg) might offer benefits while reducing palatability issues. A cross-sectional study of eight dairy herds found that adjusting DCAD to neutral values reduced clinical parturient paresis (milk fever) occurrence by an average of 87% compared to baseline. This approach might improve ration palatability by requiring lower levels of acidogenic salts.

However, more research is needed to fully validate this approach, particularly its effects on subclinical hypocalcemia and feed intake.

Immune Function Boost: An Unexpected Benefit

Research has examined whether negative DCAD diets affect immune function. Studies assessing effects on blood neutrophil function found that negative DCAD diets can improve neutrophil function in parous cows, particularly the proportion of neutrophils with killing activity. This suggests that the metabolic benefits of negative DCAD feeding may extend to improved immune function.

Long-term Performance Effects: The Gift That Keeps Giving

Controlled trials on commercial dairy farms have confirmed that feeding negative DCAD diets improved milk production in multiparous cows, particularly in early lactation. This adds to the growing body of evidence supporting the long-term performance benefits of this approach beyond just transition health.

Bottom Line: DCAD Still Delivers Results When Done Right

Negative DCAD diets remain among the most well-researched and effective nutritional strategies for managing transition cows. The evidence strongly supports their use to prevent hypocalcemia, reduce other transition disorders, and improve subsequent lactation performance, particularly in multiparous cows.

The optimal implementation involves feeding a diet with DCAD in the range of -8 to -12 meq per 100 grams of dry matter during the last three weeks before calving, monitoring effectiveness through urine pH (targeting 6.0-6.8), and ensuring adequate levels of calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus.

Essential updates to traditional recommendations include:

- Negative DCAD diets should NOT be fed to first-lactation heifers, as they may impair reproductive performance in this group.

- Moderate acidification (urine pH 6.0-6.8) is preferable to extreme acidification (urine pH below 6.0).

- After calving, cows should transition to a positive DCAD diet (+35 to +45 meq/100g DM) to support milk production.

- While negative DCAD remains the gold standard, neutral DCAD (0 ± 30 mEq/kg) shows promise as an alternative that may improve palatability while still reducing milk fever incidence.

For dairy producers seeking to optimize transition cow health and performance, implementing a well-designed negative DCAD program for multiparous cows represents a science-backed investment in cow health and farm profitability.

Key Questions for Your Nutritionist:

- What is the current DCAD level in our transition cow diet?

- Are we monitoring urine pH regularly to confirm our DCAD strategy is working?

- Should we consider separating first-calf heifers from our negative DCAD program?

- What is the cost-benefit analysis of our current DCAD implementation?

Learn more:

- Rethinking Cow Health: How Immune Activation Shapes Transition Dairy Cow Performance

Explore the role of immune activation in managing transition cow health and performance, offering fresh perspectives on metabolic stability and disease prevention. - Balancing Act: Controlled vs. High-Energy Diets for Transition Cows

Discover how tailored energy diets can reduce metabolic disorders, improve postpartum recovery, and optimize milk production during the transition period. - Mastering the Transition: A Holistic Approach to Dairy Cow Health and Productivity

Dive into evidence-based strategies for transition cow care, including nutrition, cow comfort, and inflammation management to boost herd health and farm profitability.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Daily for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!