Four bulls. Four gambles. The genetics that doubled milk production—and the hidden costs nobody saw coming.

The auctioneer’s voice cracked through the humid September air at the 1972 Hanover Hill Sale. In the ring stood a calf unlike any the Holstein world had seen—a vibrant, almost copper-red bull calf with alert eyes and legs that seemed too elegant for his age.

Ken Young sat in the crowd representing American Breeders Service, and his heart was pounding so hard he could feel it in his throat. His spending limit had evaporated three bids ago. His bosses back at the office had no idea what he was about to do.

But as Young watched that calf circle the ring, something shifted—or maybe broke—in him. Later, he wouldn’t be able to explain it fully. The balance sheet still existed. His bosses still existed. His job, his reputation, his career—all of it hung in the air every time his paddle rose. But somehow, in that moment, none of it mattered as much as what he was seeing.

His paddle went up again. And again.

When the gavel finally fell at $60,000—a world record for a Red & White Holstein—the room didn’t just react. It erupted. Breeders who’d spent entire careers avoiding red genetics stood slack-jawed. Young would later face his superiors with a response that has echoed through dairy breeding lore for over fifty years:

“It was easier to ask for forgiveness than to ask for permission.”

That red calf was Hanover-Hill Triple Threat. And here’s what stays with me about his story—along with three other legendary bulls whose genetics would reshape the dairy industry—it’s not really about DNA or milk production quotas at all. It’s about people who saw possibilities where others saw problems. About farmers and breeders who bet their reputations on their convictions. About the complicated, sometimes painful dance between ambition and consequence that defines every great leap forward.

Triple Threat: The Man Who Wouldn’t Go Home

Before Ken Young’s legendary bid, before Triple Threat drew his first breath, there was a young Swiss agricultural graduate named Jean-Louis Schrago standing in the rolling farmland of Ontario with nothing but conviction and what must have seemed like a crazy idea.

It was 1968. Schrago had traveled across the Atlantic because he’d seen something the North American dairy establishment couldn’t—or wouldn’t—see. In Europe, there was a market starving for elite red genetics. But in North America, a red and white coat on a Holstein wasn’t just unfashionable. It was treated as a genetic mistake, a defect to be culled from the herd. Red calves were barred from the prestigious main herdbook, their potential sealed away before they ever had a chance.

Schrago refused to accept this.

His search led him to Pete Heffering of Hanover Hill Holsteins, where he proposed something that made experienced breeders shake their heads: breed one of your finest cows to a red-factor bull. Heffering, understandably, shut him down.

Most people would have gone home after that. Most people would have accepted that the industry knew better, that maybe the establishment was right. I’m not sure how Schrago found the stubbornness to keep going—three years of being dismissed, three years of industry veterans suggesting, politely and not so politely, that he was wasting his time. Whatever doubts he harbored (and he must have had them, because anyone who’s ever chased an unpopular idea knows those 3 AM moments of wondering if everyone else is right), he kept them to himself.

He returned in 1971 with a plan so audacious it bordered on the miraculous. He’d found his answer in Roybrook Telstar—a Canadian superstar celebrated for refinement and exceptional udders. What most didn’t know was that Telstar carried the rare “Black-Red gene.” There was just one problem: Telstar had been exported to Japan.

What happened next speaks to the lengths dreamers will go when something inside them refuses to quit. Schrago located two precious units of semen on the other side of the Pacific and arranged their importation for $2,500—serious money in 1971. He then convinced Heffering to use Telstar on Tara-Hills Pride Lucky Barb, a phenomenal cow who carried the true recessive red gene.

The genetic math was elegant. The wait was agonizing.

On April 24, 1972, a vibrant red calf slid into the world. Schrago would later describe him with words that still carry wonder: “He looked like a small deer—delicate, alert, unmistakably special.”

Standing in that barn, watching that calf find his legs—I think about what that moment must have felt like. Three years of persistence. Continents crossed. Skeptics ignored. And now, this small creature blinking in the light, carrying the genetic blueprint that would change everything.

Schrago would spend the rest of his life championing Red Holstein genetics, eventually founding ABC Genetics in Switzerland and becoming one of the breed’s most influential advocates. He passed away in December 2017 after a battle with cancer, but his vision lives on in every crimson champion that enters a show ring today. Some dreams outlive the dreamers.

What Made Triple Threat a Legend

That calf didn’t just break the color barrier. He shattered it.

At a time when Red & White Holsteins were considered genetic afterthoughts, Triple Threat injected elite refinement into the population in a single generation. His daughters were tall, angular, with superior udder texture and exceptional feet and legs. They transmitted high butterfat percentages when the industry was obsessed with volume alone—a trait that proves even more valuable in today’s component-focused markets.

But perhaps the most beloved part of his legend came from adversity. A leg injury in his mature years earned him the nickname “the three-legged bull.” Whether literally true or lovingly embellished by the industry over time, the message resonated: this bull kept working. His drive, his resilience, his constitutional strength—these weren’t just traits he possessed. They were gifts he passed to generation after generation of long-lasting, productive daughters.

Triple Threat never produced a famous line of sons. He was a “daughters bull” through and through. But those daughters? They became matriarchs who founded dynasties that continue to shape the breed today.

Consider KHW Regiment Apple-Red—known as “The Million Dollar Cow” and arguably the most influential Red Holstein of the 21st century. She carries the red factor passed from Triple Threat through his son Meadolake Jubilant to her granddam. Without Schrago’s persistence, without Young’s unauthorized bid, Apple doesn’t exist. Neither do thousands of elite Red & White animals milking in herds around the world today.

At the 2025 National Red & White Show in Toronto, Golden-Oaks Temptres-Red walked away as Grand Champion under Judge Steve Fraser—then went on to claim Supreme Champion at World Dairy Expo. Another link in the chain, Triple Threat, started over fifty years ago.

I was talking with a Wisconsin breeder at a show last fall, watching her prep a gorgeous red heifer, when I asked what Triple Threat meant to her program. She didn’t hesitate.

“When I lead a red cow into the ring, I’m leading fifty years of people refusing to quit. That’s Triple Threat’s real legacy. Not just the color—the stubbornness.”

Something about the way she said it—matter-of-fact, like she was stating the obvious—struck me. She wasn’t being sentimental. She was being precise.

This is Golden-Oaks Temptress-Red-ET—the 2024 World Dairy Expo Supreme Champion who just dethroned a three-time reigning queen. Fifty-two years after Ken Young bet his career on a red calf nobody wanted, a Red & White Holstein stood at the pinnacle of the most prestigious show on earth. That’s the arc of Triple Threat’s legacy. From $60,000 gamble to Supreme Champion crowns. From “cull her, she’s red” to the kind of type that makes judges stop and stare.

Carlin-M Ivanhoe Bell: The Devil’s Bargain

The story of Carlin-M Ivanhoe Bell begins not with a master plan, but with two Kansas dairy farmers who had no idea they were about to change the history of breeding.

John Carlin and Lawrence Mayer were partners in a Holstein breeding operation. Carlin would later serve as governor of Kansas from 1979 to 1987, and eventually as Archivist of the United States—but in the early 1970s, he was simply a dairy farmer making breeding decisions the same way everyone else did: with instinct, visual appraisal, and faith in pedigree knowledge.

In an era before genomic testing, Select Sires agreed to mate Creamelle to Penn State Ivanhoe Star. The result was a bull named Carlin-M Ivanhoe Bell—co-bred by Carlin and Mayer.

And Bell changed everything.

His primary impact was dramatic: he offered an unprecedented promise of milk production that breeders had only dreamed of. Daughters that poured milk. Numbers that seemed impossible. The dairy industry, hungry for progress, embraced him with open arms.

But genetic progress, it turns out, can carry hidden costs. And what came next would force an entire industry to confront what it means to wield that kind of power.

The Phone Calls Nobody Wanted to Make

In 1999, Danish researchers made a startling discovery. They’d been tracing a lethal genetic disorder called Complex Vertebral Malformation (CVM) through countless pedigrees, following the trail backward through generations of breeding records. In every single case, when traced to its source, it led to one animal.

Carlin-M Ivanhoe Bell.

He was also found to carry another lethal recessive gene, Bovine Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency (BLAD). Unusually, Bell carried both—a genetic burden no one could have detected with the tools available when he was in active service.

What the clinical language doesn’t capture is what this meant for the people who had built their breeding programs around Bell’s genetics.

Imagine the phone calls. Imagine being a breeder who had used Bell heavily for years—trusting the system, trusting the science as it existed—and then learning that you’d been unknowingly producing calves destined to die. The guilt doesn’t arrive all at once. It comes in waves. Every calf you remember losing and couldn’t explain. Every breeding decision you made with confidence. The science told you Bell was the future. And he was. But he was also carrying something nobody could see.

One industry veteran—we spoke at a breeding conference a few years back—described those months after the discovery as “the longest year of my career.” Breeding decisions that had seemed brilliant now felt reckless, even though everyone had been operating with the best information available at the time.

“We weren’t careless,” he said, and there was something in his voice—not defensiveness, exactly, but a kind of hard-won peace with an impossible situation. “We just didn’t know what we didn’t know.”

I think about that phrase often. It captures something essential about the Bell story—and about progress itself. Every generation works with incomplete information. Every breakthrough carries risks we can’t yet see. The question isn’t whether we’ll make mistakes. It’s what we do when we discover them.

The Bell crisis forced an entire industry to grow up. An age of innocence and trust gave way to an era of accountability and data. His story became the catalyst for widespread genetic testing, carrier screening, and the mandatory disclosure requirements that protect the breed today.

Here’s what makes Bell’s legacy so complicated, so deeply human: his genetics had genuine staying power. His contribution to production potential was so immense that breeders learned to manage the risks rather than abandon his line entirely. They screened matings carefully, avoided producing affected calves, and over time, perfected the Bell line—harnessing its power while mitigating its flaws.

In 2016, Sheeknoll Durham Arrow—a daughter of Bell descendant Regancrest Elton Durham—was crowned Grand Champion of the International Holstein Show at the World Dairy Expo. Proof that with wisdom and responsibility, even a complicated legacy can produce champions.

Today, Bell’s story is why genetic testing isn’t optional anymore—it’s foundational. Every screening panel, every carrier designation, every transparent disclosure traces back to what we learned the hard way from one bull’s hidden burden.

The ultimate proof of successful line breeding. Sheeknoll Durham Arrow, a daughter of the legendary Bell descendant Regancrest Elton Durham, was crowned Grand Champion at the 2016 World Dairy Expo, showcasing how breeders perfected the Bell line to achieve both elite, show-winning type and immense production.

Read more: Bell’s Paradox: The Worst Best Bull in Holstein History

The King of Milk

The story of Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief begins in the heart of Nebraska, with a man named Lester Fishler who fellow breeders simply called gifted.

Fishler founded his Pawnee Farm on the southern edge of Central City, Nebraska—practically within the city limits—methodically building what he proudly called a “strictly Rag Apple” herd. He could look at a cow and see generations forward. Not magic—just thousands of hours of paying attention when others had stopped looking. His breeding records suggest a man who thought in decades, not seasons. Every mating decision was part of a larger architecture only he could see.

Where others selected for next year’s milk check, Fishler was building toward something he might never see completed.

And that’s exactly what happened.

On April 14, 1962, the Pawnee Farm herd was dispersed at auction, with potential buyers from seven states gathering in Central City. In the crowd sat Wally Lindskoog of Arlinda Farms in California, with instructions and a spending limit that was about to be tested.

The bidding war for a pregnant cow named Pawnee Farm Glenvue Beauty was fierce. Other buyers saw a good cow. Lindskoog saw something more—or at least, he was willing to bet that Fishler had seen something more when he bred her. His paddle kept rising until he secured her for $4,300—a sum that raised eyebrows and probably a few concerns back home.

Twenty-five days after Beauty arrived by train in Turlock, California, she gave birth to a bull calf on May 9, 1962. That calf would make that $4,300 look like the bargain of the century.

They named him Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief.

His journey nearly ended at eight months old. A severe case of bloat—the kind that kills calves in hours—almost claimed his life. I try to imagine that scene: a young bull gasping for air, the frantic veterinary intervention, everyone who believed in his potential watching and waiting and hoping. The hours before anyone knew if he’d survive.

Chief survived. He developed into a deep-bodied bull with a trademark ravenous appetite that seemed to foreshadow the milk-producing machines his daughters would become.

Fishler never saw any of it. He passed away before Chief’s first daughters ever freshened, before anyone knew what his careful breeding had created. All those years of patient work, and he never got to see the payoff. That’s the part of this story that catches in my throat.

“One of the Great Milk Bulls of All Time”

Chief’s defining genetic gift was an extraordinary, almost relentless ability to transmit massive milk production. His daughters were known for their deep bodies, wide fronts, and an appetite that fueled incredible output. Breeders called it “the will to milk”—a drive that seemed to pulse through every animal that carried his genetics.

The herdsman at Arlinda Farms watched Chief’s first four daughters freshen. Just four. But what he saw in those four animals—the depth of body, the capacity, the way they hit the feed bunk hard and then walked to the parlor like they were ready to work—told him everything. These weren’t just good cows. These were a different kind of cow.

“One of the great milk bulls of all time,” he declared.

After just four daughters. He’d seen enough.

And he was right.

Chief became one of the most genetically dominant sires in the history of any livestock breed. His genetic contribution is estimated at 14.95% of the entire Holstein genome—nearly one-sixth of every Holstein alive today traces back to this one bull. A staggering concentration that no one planned for and few saw coming until it was already a reality.

The revolution: Chief’s genetics helped double the milk volume of the average Holstein cow. Billions of dollars in value added to the global dairy industry. Efficiency gains that fed families and sustained farms through decades of economic pressure.

The risk: With so many animals tracing back to a single sire, genetic diversity narrowed in ways the industry is still working to address. The breed became more efficient but also more vulnerable, its genetic foundation more concentrated than anyone had intended.

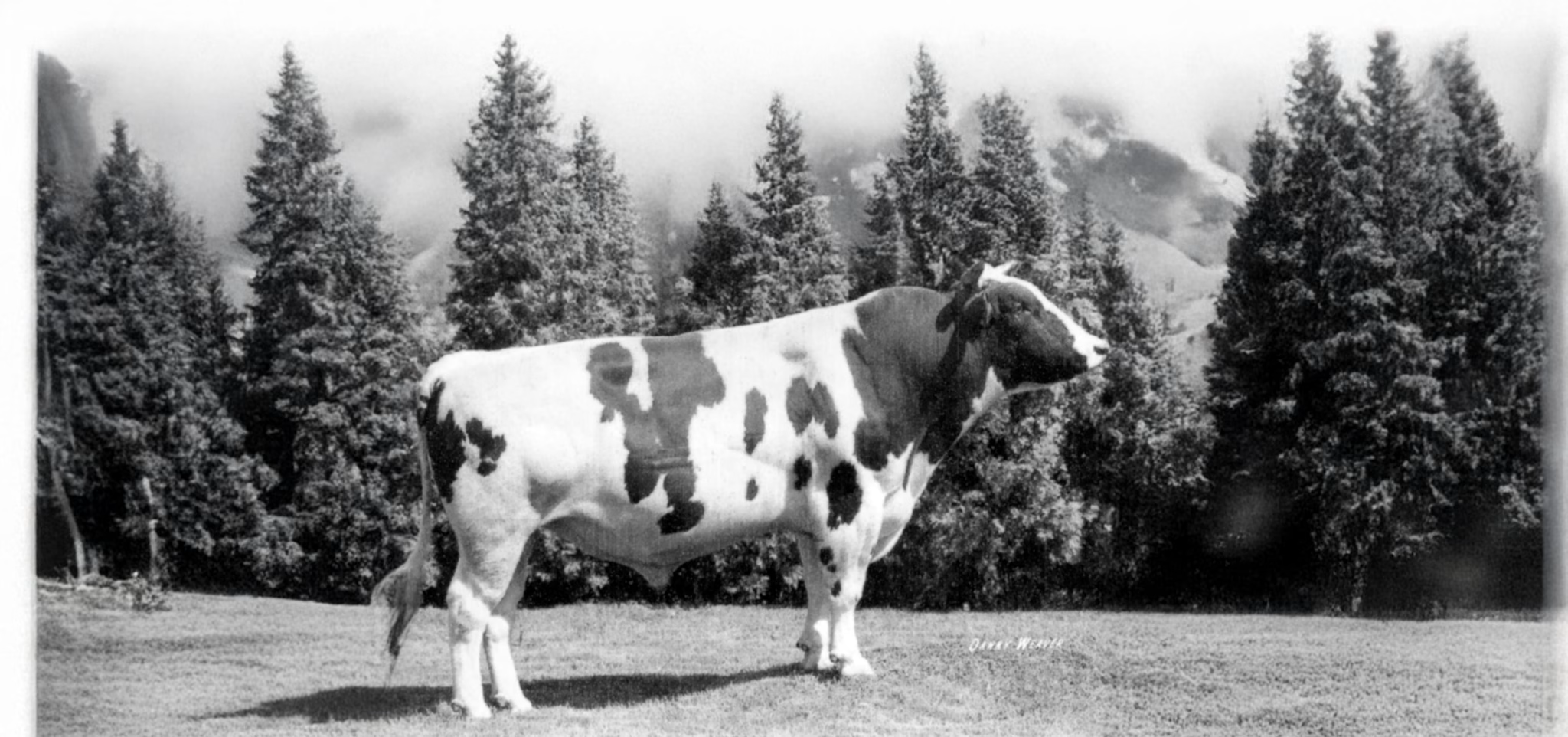

O’Katy, a stunning 3-year-old Stantons Chief daughter and descendant of the legendary Decrausaz Iron O’Kalibra, shines as Grand Champion at Schau der Besten 2025, proudly carrying on Chief’s enduring legacy in modern Holstein breeding.

Read more: The $4,300 Gamble That Reshaped Global Dairy Industry: The Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief Story

The Total Package

S-W-D Valiant was born from a mating many considered foolish. His sire was the milk production king, Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief. But his dam, Allied Admiral Rose Vivian, had what breeders diplomatically called a “questionable udder”—she scored VG-85 overall, but only “Good Plus” on her mammary system.

The decision to make that mating wasn’t made lightly. Someone looked at Rose Vivian’s flaws, looked at Chief’s raw power, and decided to roll the dice anyway. History doesn’t record who made that call, but it should. Because sometimes in genetics—as in life—the math doesn’t predict what actually happens. A flawed dam. A dominant sire. And somehow, a calf that inherited exactly what he needed and left behind exactly what he didn’t.

But nobody knew that yet. For years, Valiant was just another young bull waiting for his daughters to freshen, waiting for the data to come in. The industry had seen plenty of promising pedigrees disappoint. There was no reason to assume this one would be different.

And then… in July 1978, the numbers on Valiant’s first proof stopped conversations in dairy co-ops from Wisconsin to California. The figures seemed almost impossible: +1,541 pounds of milk, +44 pounds of fat, AND top type scores.

You have to understand what this meant. Bulls delivered either high production or elite type. Finding both at world-class levels in a single animal was like finding a pitcher who could also hit home runs. It just didn’t happen.

Valiant was the “total package.”

The 1980s became his era. His daughters, described by those who saw them as animals that “milked like machines and looked like movie stars,” dominated both the parlor and the show ring. Champions wearing his genetics claimed banners at major shows across North America.

His son Fisher-Place Mandingo reportedly became the first bull in history to sell a million doses of semen—a testament to the industry’s insatiable appetite for Valiant’s genetics. Another son, Hanover-Hill Inspiration, launched a genetic line so powerful it produced later legends like Goldwyn, Shottle, and Storm—names that anyone who’s bought semen in the last two decades will recognize instantly.

The Warning Nobody Wanted to Hear

Valiant’s incredible success created the ultimate cautionary tale about what happens when the industry falls in love with one animal too completely.

By January 1987, thirty-one of the top 100 TPI bulls were Valiant sons, and ninety-eight of the top 400 carried his genetics. Let that sink in. Nearly a quarter of the breed’s genetic elite, all connected to one sire. The industry had put too many eggs in one genetic basket, and few people were asking what would happen if some of those eggs were cracked.

Modern DNA research has shown that Valiant himself didn’t carry the HH1 genetic defect that his sire, Chief, passed along. But his story remains the primary example of what happens when success breeds overuse. When a single sire is used so extensively, it amplifies the risk of spreading both known and unknown problems through the population.

I had coffee with an Ontario breeder after a show last year, and when I asked about his mating philosophy, his answer surprised me with its directness.

“Every mating decision I make, I think about what happened with Bell and Valiant,” he said. “That history isn’t academic for us—it’s operational. It’s why I check inbreeding coefficients before I check anything else.”

He paused, stirring his coffee, then added something that’s stuck with me: “Those bulls taught us what happens when we get careless with concentration. The lesson cost the breed. I’d rather learn from their mistakes than make my own.”

Du-Ma-Ti Valiant Boots Jewel EX-93 DOM 8*, a celebrated Valiant daughter, was a dominant force in the show ring, taking home Grand Champion honors at the Royal Winter Fair and Reserve Grand at the International Holstein Show in 1988. Her powerful genetics and classic type were a testament to her sire’s legacy, earning her numerous All-American and All-Canadian titles.

Today, Valiant’s modern genetic evaluations show negative numbers. If you didn’t know the history, you might wonder why anyone ever used him. But those numbers aren’t an indictment—they’re a measuring stick. They show how far the breed has traveled since his reign, how much genetic progress has accumulated in the decades since he dominated every proof sheet.

Read more: The S-W-D Valiant Story: How Genetics Promised Everything and Changed How We Think About Breeding

What These Bulls Mean for Us Now

After months of interviews, archives, and late-night reading, what stays with me isn’t the genetics. It’s the people.

Schrago, waiting years for a vision nobody shared, crossing oceans for two units of semen because something inside him wouldn’t let go. Young, raising his paddle past all reason because some moments demand courage over caution—and hoping, probably, that his bosses would eventually understand. Fishler, building a breeding program cow by cow toward a future he’d never see. The unnamed breeder who decided to mate Chief to a cow with a questionable udder, taking a chance that no spreadsheet would have recommended.

These weren’t reckless people. They were people who understood that the safest path rarely leads anywhere worth going—and that the price of never risking anything is never building anything either.

But they also learned—sometimes painfully—that risk without responsibility is just gambling. That power without accountability leaves wreckage. That the greatest gift you can give the next generation isn’t just better genetics, but the wisdom to use them well.

If you’re breeding cattle today, you’re working with tools these four bulls helped create. Every genetic screen you run before making a mating decision exists because of what Bell taught us. Every Red & White animal that freshens with elite type and components carries Triple Threat’s dream forward. Every time you think about genetic diversity and concentration risk, you’re standing on lessons Chief and Valiant paid for.

Their legacies aren’t just in the tank or the show ring. They’re in every AI training program that teaches young geneticists about concentration risk. They’re in every breeding company’s diversity guidelines. They’re in the quiet moment when a breeder pauses before using the hottest bull in the lineup and asks: “Is this wise, or just popular?”

In the genomic era, where we can map a calf’s potential before she takes her first breath, these lessons matter more than ever. Today’s tools give us power Schrago and Fishler could only dream of—and responsibility to match. Young bulls can achieve widespread use faster than Chief or Valiant ever did. The temptation toward concentration hasn’t diminished. It’s accelerated.

But so has our wisdom. Because of these four bulls—and the people who bred them, bought them, used them, and learned from them—we know better now. We test before we trust. We balance power with diversity. We ask harder questions earlier.

The next bull who builds the breed is being born somewhere today. Maybe on your farm. Maybe on mine. The question isn’t whether we’ll find him.

The question is whether we’ll have the wisdom to use him well.

| Bull | Primary Contribution | The “Hidden Cost” | Modern Legacy |

| Triple Threat | Refinement, Red Factor, Components | Industry Skepticism/Barriers | Foundation of the Red & White Breed |

| Ivanhoe Bell | Massive Milk Production | Lethal Recessives (CVM/BLAD) | Catalyst for Mandatory Genetic Testing |

| Arlinda Chief | 15% of Holstein Genome; Output | Extreme Genetic Concentration | Efficiency gains; Doubled Milk Yields |

| S-W-D Valiant | The “Total Package” (Type + Production) | Bottlenecking; Overuse of Sires | The standard for “Balanced Breeding” |

Key Takeaways

- What the industry calls a defect, a dreamer might call an opportunity: Triple Threat’s dismissed red coat became the foundation of modern Red Holsteins after one unauthorized $60,000 bid

- Trust, but verify—then trust: Bell revolutionized production but carried hidden lethal genes for decades; his crisis gave us the genetic testing that protects the breed today

- Concentration is a feature until it becomes a risk: Chief’s DNA runs through 15% of all Holsteins—doubling milk yields while creating diversity challenges we’re still managing

- Even greatness requires restraint: Valiant’s “total package” success became the textbook example of why overusing any sire creates dangerous genetic bottlenecks

- Before using the hottest bull in the lineup, ask the question that matters: Is this wise, or just popular?

Executive Summary:

Every Holstein alive carries genetics shaped by four bulls—and four breeders who bet everything on their convictions. Ken Young’s $60,000 bid for a “defective” red calf gave us Triple Threat, who built the modern Red Holstein from an animal the industry had written off. Carlin-M Ivanhoe Bell delivered revolutionary production but carried lethal genes undetected for decades; his legacy is both the milk in your tank and the genetic testing that now protects the breed. Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief contributed 15% of all Holstein DNA—doubling milk yields while creating concentration risks we’re still managing today. His son Valiant offered the “total package” but became the industry’s starkest lesson in why even greatness requires restraint. For anyone making breeding decisions now, these aren’t just origin stories—they’re the hard-won wisdom that separates building something lasting from repeating costly mistakes.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!