$4.4M in federal aid—still not enough. The $950/cow figure? It doesn’t count the high-genomic 2-year-old you had to cull because her quarter dried off.

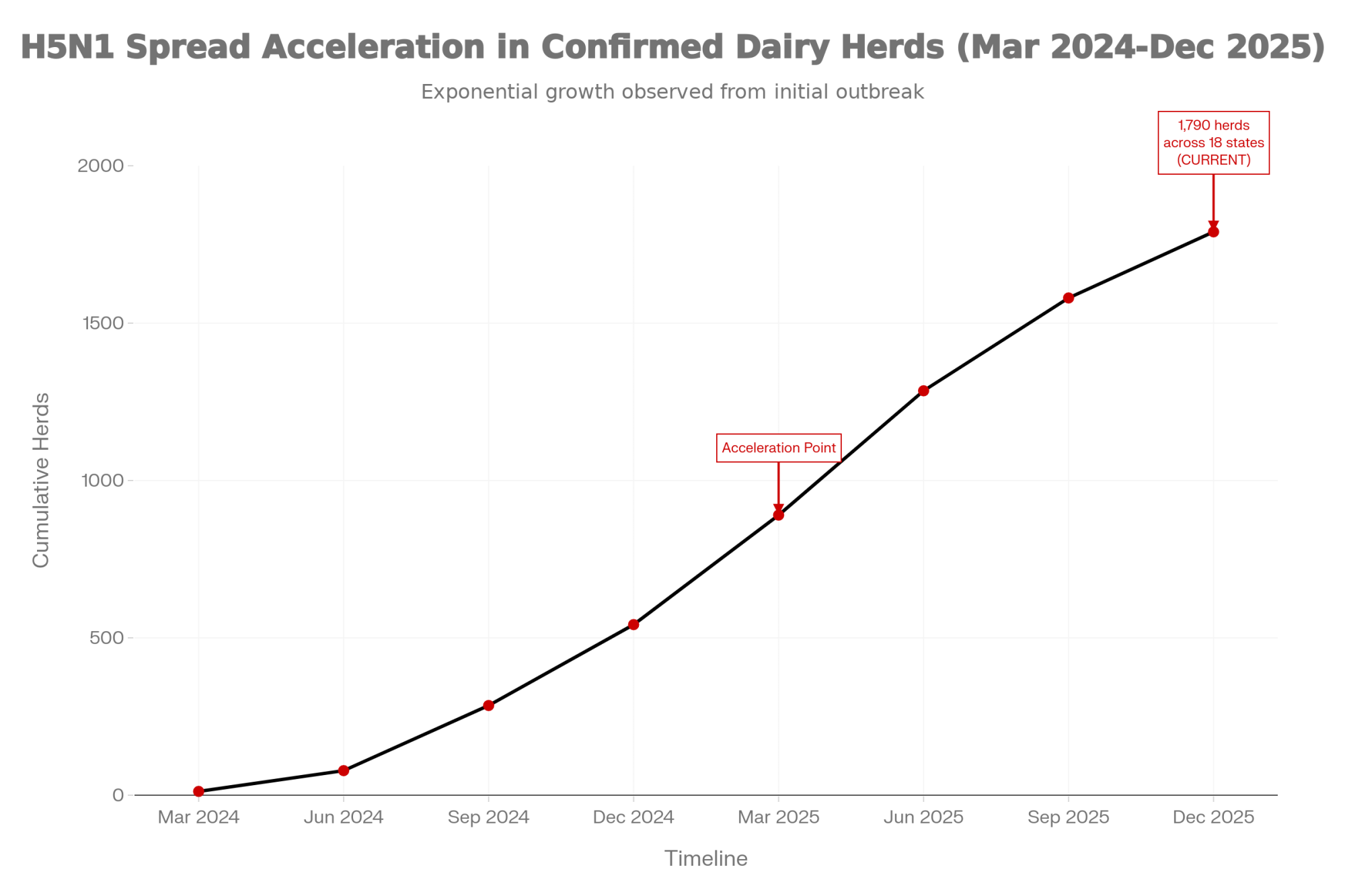

Executive Summary: Cornell’s research puts H5N1 losses at $950 per clinically affected cow. Farmers who’ve lived through outbreaks say that’s just the starting point. The study tracked direct losses over 67 days but explicitly excluded breeding setbacks, lost premiums, and the genetic value of high-genomic animals you’re forced to cull—costs that compound long after the acute phase ends. One California dairyman received $4.4 million in federal aid and says his actual losses exceeded it. With 1,790 herds confirmed across 18 states and vaccine approval stalled by trade politics, the outbreak keeps growing, while biosecurity alone can’t stop a virus that spreads through workers traveling between farms. The playbook for producers: document every cost obsessively, fortify your financial reserves, and push your representatives hard—because we have the tools to fight this, and every month of delay is money out of your pocket.

You’ve probably heard the official estimate—about $950 per clinically affected cow. But farmers who’ve actually lived through H5N1 outbreaks are finding the true cost runs considerably higher. Here’s what the research shows, why it matters for your operation, and where things are headed.

Jonathan Cockroft didn’t need anyone to explain the math to him. When H5N1 swept through his Channel Islands Dairy Farms operation in California earlier this year, the federal indemnity payment came to about $4.4 million. His actual losses? They exceeded that figure—and kept climbing as the ripple effects moved through his breeding program and production cycle.

“The check helps,” Cockroft told the Los Angeles Times this past July. “But it doesn’t cover what we actually lost.”

And you know, his experience isn’t unusual. As of early December, USDA APHIS data shows H5N1 has spread to roughly 1,790 confirmed herds across 18 states. That’s a significant jump from where we were even six months ago. Dairy producers from California’s Central Valley to Wisconsin’s dairy heartland are getting a hard education in the gap between official loss estimates and what actually shows up on the balance sheet.

Understanding that gap isn’t about pointing fingers at anyone. It’s about helping you make informed decisions—about biosecurity investments, about financial planning, about the policy conversations happening right now in Washington.

The Economic Gap: What Research Measures vs. What Farms Experience

| Metric | Official Research (Cornell) | On-Farm Reality |

| Loss Per Cow | ~$950 in direct, quantifiable losses | Direct losses + premiums, genetics, labor surge |

| Recovery Timeline | 67-day acute observation period | Months before production normalizes |

| What’s Captured | Milk loss, mortality, and early culling | Breeding setbacks, SCC penalties, overtime costs |

| Key Gap | Measures the acute phase | Hidden costs compound across seasons |

Source: Cornell University, Nature Communications, July 2025. On-farm observations from producer reports and USDA epidemiological summaries.

What the Official $950 Figure Actually Measures

Let’s start with what that number represents, because here’s the thing—it’s not wrong. It’s just measuring something specific.

That $950 figure comes from Cornell University research published in Nature Communications this past July. The researchers followed an Ohio dairy operation through a full H5N1 outbreak and documented direct economic losses per clinically affected cow, including decreased milk production, mortality, and early removal from the herd.

The study was thorough. They tracked a herd with 776 clinically affected lactating cows over a 67-day observation period and found total production losses averaging around 945 kilograms—that’s over 2,000 pounds, or nearly a ton of milk—per clinically affected cow. For that group, total documented losses came to approximately $737,500.

Fair enough. But what farmers on the ground are discovering is that the acute phase is really just the beginning of the story.

The Hidden Costs That Keep Adding Up

Recovery takes longer than the paperwork suggests. The Cornell team documented production impacts lasting at least two months in clinically affected cows, and many veterinarians and producers report that getting a herd back to its pre-outbreak groove can take considerably longer—especially when older cows or stressed transition cows are hit hard. Production doesn’t just snap back to baseline when clinical signs resolve. Some animals never fully recover their previous peak.

Reproductive impacts hit breeding programs hard. This is where operations with strong genetic programs really feel it. Abortion rates spike during outbreaks. Conception rates drop. Breeding cycles get disrupted in ways that take a full lactation cycle to sort out. I’ve spoken with producers who say they’re setting their breeding programs back a year or more.

For a Bullvine reader, this is the heartbreak. When you cull a high-genomic 2-year-old because her quarter dried off from H5N1, you aren’t just losing a cow—you’re losing the dam of your next sire analyst contract.

When you’ve invested years in genomic selection and careful mating decisions, watching that progress unravel is devastating—and none of that shows up in the per-cow calculation.

Quality premiums disappear. For operations built around butterfat performance or somatic cell count bonuses—and that’s a lot of farms in Wisconsin and the Northeast, especially—H5N1 is particularly brutal. SCC spikes during and after infection can disqualify milk from premium markets. A farm earning an extra dollar-fifty to two dollars per hundredweight on quality bonuses can watch that revenue stream vanish overnight. And rebuilding those numbers takes months of careful fresh cow management and culturing.

The labor-management surge is real. Farmers who’ve been through it describe round-the-clock monitoring during acute phases, increased veterinary visits, enhanced biosecurity protocols, and staff overtime. These costs don’t appear anywhere in the official calculations—they just get absorbed into that season’s operating expenses.

Genetic losses compound over the years. This one’s harder to put a number on, but it matters enormously if you’ve invested in your breeding program. When high-value animals are culled due to permanent udder damage or reproductive failure, decades of selection work can be undone. Anyone who’s built a herd over generations understands exactly what I’m talking about.

What This Means for Your Planning

So what does the true picture look like? Well, that depends on your operation. The Cornell research gives us a solid baseline of about $950 per clinically affected cow for direct, quantifiable losses. But—and here’s the key part—the researchers specifically note that their estimate doesn’t capture longer-term reproductive impacts or changes in herd structure.

Because of that gap, economists and producers expect the true long-run cost per affected cow to be higher than $950 once those additional factors are accounted for. How much higher depends on your genetics program, your premium market position, and how hard the outbreak hits your best animals.

For a 500-cow dairy experiencing a typical outbreak affecting 15-20% of the herd, even using just the verified $950 figure, you’re looking at direct losses of roughly $70,000-$95,000. Add in those hidden costs—the extended recovery period, the breeding setbacks, the lost premiums—and the true impact grows from there.

Cost Category | Cornell Study Captured? | Cost Per Cow (USD) | Timeline/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk production loss (acute phase) | Yes | $620 | 67-day observation period; ~945 kg lost per cow |

| Mortality & immediate culling | Yes | $230 | Direct animal replacement costs during outbreak |

| Acute veterinary & treatment | Yes | $100 | Medications, diagnostics, emergency care |

| Extended production depression | No | $140 | 2-4 months post-clinical recovery; partial production |

| Breeding setbacks & abortions | No | $280 | 6-12 months; delayed conception, lost calves |

| Quality premium losses (SCC/BF) | No | $180 | 3-6 months to rebuild; varies by market |

| High-genomic animal genetic value | No | $100 | Permanent; irreplaceable selection progress |

| Labor surge & biosecurity operations | No | $85 | Outbreak duration + 30 days; overtime, PPE, monitoring |

| TOTAL VERIFIED (Cornell) | — | $950 | What indemnity calculations use |

| TOTAL TRUE COST (full cycle) | — | $1,735 | What your balance sheet actually shows |

That’s a different planning conversation than the official numbers alone might suggest. And it helps explain why farmers like Cockroft find indemnity payments—helpful as they are—falling short of actual economic damage.

The Biosecurity Investment Question

Given those numbers, one of the most practical questions on everyone’s mind is straightforward: How much should I invest in enhanced biosecurity, and will it actually protect my operation?

What we’re seeing in the data is more nuanced than any of us would prefer.

The cost picture is clearer than the effectiveness picture. USDA’s current support program offers up to $28,000 per premises for biosecurity improvements, covering a significant portion of equipment and infrastructure costs. That’s genuinely helpful. But when you work through what comprehensive implementation actually requires—enhanced disinfection systems, dedicated PPE facilities, separate equipment for different areas of operation—the investment adds up quickly. And then there are ongoing operational costs for uniform laundering, PPE supplies, and additional labor that continue month after month.

Now for the harder question: does it work?

USDA’s epidemiological audits of affected dairy operations revealed something that complicates this conversation. Even farms with enhanced biosecurity protocols in place experienced continued transmission in a meaningful percentage of cases.

The reason isn’t that farmers are doing something wrong—and I want to be really clear about that. It’s that the primary transmission pathway operates at a level that individual farm protocols can’t fully address.

The Network Problem Worth Understanding

Here’s what I’ve found most eye-opening in reviewing the outbreak investigations: the role of worker mobility.

According to USDA APHIS epidemiological summaries reported by CIDRAP, about 20% of dairy workers on affected farms also work on other dairy operations. About 7% of workers on affected dairy farms also worked on poultry farms. And roughly 62% of farms shared vehicles for transporting cattle, with only about 12% cleaning them before use.

Think about what that means from a practical standpoint. The virus can travel on boots, clothing, and equipment between operations. It’s not that anyone is being careless—it’s the structural reality of how dairy labor markets function, especially in regions where farms are smaller and can’t always offer forty hours a week year-round. Workers need income from multiple sources. The resulting movement creates transmission pathways that no individual operation can fully control, no matter how good their on-farm protocols are.

The takeaway for most of us is this: biosecurity investments remain valuable. They reduce risk, demonstrate due diligence, and protect against multiple disease threats beyond just H5N1. But under current conditions, even excellent protocols provide only risk reduction, not elimination. Any farmer evaluating biosecurity spending should factor that reality into their calculations—and into their financial planning for potential outbreak scenarios.

Biosecurity Measure | Typical Investment | Risk Reduction Potential | Limitation/Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced disinfection stations | $8,500-$12,000 | Moderate (30-40% reduction in surface contamination) | Doesn’t address worker clothing/vehicle transfer between farms |

| Dedicated PPE & laundering systems | $6,000-$9,500 + $400/month ongoing | Moderate-High (50-60% reduction in barn-to-barn spread) | Limited if workers commute from other dairy operations |

| Visitor/vendor protocols & separate entry | $3,500-$7,000 | Low-Moderate (20-35% reduction in external introduction) | Feed trucks, milk haulers, and AI technicians still cross farms daily |

| Cattle movement quarantine protocols | $2,000 + $150/head quarantine cost | High (60-70% reduction from purchased cattle) | 62% of farms share cattle transport vehicles; 12% clean between use |

| Worker health monitoring & education | $1,500-$3,000 + staff time | Moderate (35-45% reduction in symptomatic transmission) | 20% of dairy workers work multiple operations; 7% also work poultry farms |

| TOTAL comprehensive implementation | $21,500-$35,000 upfront + ~$600/month | Cumulative: 40-55% risk reduction | Even farms with “enhanced protocols” experienced continued transmission in USDA audits |

| USDA biosecurity cost-share available | Up to $28,000 per premises | Covers 65-80% of upfront investment | Doesn’t eliminate the transmission network problem |

Where Things Stand on Vaccines

No topic generates more questions in dairy right now than vaccination. Let me walk you through what we actually know versus what’s still developing, because there’s a lot of incomplete information floating around out there.

On the product side, Medgene Labs has developed an H5N1 vaccine for cattle, and they’re working with Elanco for commercial distribution. According to Hoard’s Dairyman reporting from March, the vaccine has met all requirements of USDA’s platform technology guidelines and is in the final stages of review for conditional license approval.

Alan Young, Medgene’s Chief Technical Officer, told Agri-Pulse earlier this year that they’re confident the data meets expectations for conditional licensure. So the product exists and appears to work. The holdup is elsewhere.

What’s slowing things down? Several factors are at play, and I want to present them fairly because reasonable people disagree about the tradeoffs involved.

Trade concerns from the poultry sector have been significant. The National Chicken Council and related organizations have expressed worry that vaccination—even limited to dairy—could trigger trading partner restrictions affecting poultry exports. Their concern is that any U.S. vaccination program signals endemic infection to foreign markets, potentially closing doors for chicken and turkey products. Given that U.S. chicken exports alone totaled about $5 billion in 2024, according to industry data, that’s a substantial consideration. We shouldn’t dismiss it out of hand, even if we might weigh the tradeoffs differently.

USDA leadership has also cited a desire for additional field data. Secretary Brooke Rollins told Agri-Pulse in March that there’s “a tremendous amount of work to do before we would even consider that as a potential solution” and that vaccination remains “at least a year or more away.” Whether you agree with that timeline or not, it’s worth noting that regulatory agencies tend to be cautious, especially when trade implications are involved.

What dairy industry leaders are saying is a bit different. The National Milk Producers Federation, International Dairy Foods Association, and multiple state dairy organizations have called for accelerated vaccine deployment. IDFA President Michael Dykes stated in February that the industry continues to “urge USDA and its federal partners to act quickly to develop and approve the use of safe, effective bovine vaccines.” There’s genuine frustration in the dairy community about the pace of progress.

Here’s what I find particularly noteworthy about the trade concern: restrictions are arriving regardless of vaccination status. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has implemented testing requirements for dairy cattle imports. EU food safety and animal health agencies have raised concerns about H5N1 in U.S. dairy in their risk assessments. Australia and several other markets have enhanced their protocols.

That reality suggests the original calculus around vaccination and trade may need updating. If restrictions are emerging based on infection presence rather than vaccination policy, the argument for delaying vaccines to protect trade relationships becomes less compelling. But these are genuinely complex tradeoffs, and I don’t think anyone has a monopoly on the right answer here.

The Viral Evolution Picture

For farmers trying to assess longer-term risk, let me explain what researchers are watching on the scientific side—because it matters for understanding the urgency of this issue.

The concern among virologists is that continued circulation in mammalian populations increases the likelihood that the virus will acquire mutations that enhance transmission. Each additional month of cattle-to-cattle spread means more viral replication cycles, and with more replication comes more chances for random mutations—most of which are neutral, but some of which could matter.

A newer variant designated D1.1 has been detected in dairy cattle. According to WeCAHN tracking data, it was first confirmed in Nevada on January 31, 2025, and then identified in Arizona on February 11. Some field reports suggest that D1.1-positive herds are seeing more noticeable respiratory signs alongside mastitis, though researchers are still working to define that pattern.

The third major concern—full adaptation for efficient human-to-human transmission—hasn’t been observed. Current human cases remain sporadic with no sustained person-to-person spread documented. But the scientific consensus is that the longer this virus circulates in mammalian populations, the more opportunity it has to evolve in concerning directions. That’s not cause for panic. But it does underscore why public health officials, veterinary researchers, and dairy industry leaders are pushing for faster action.

What Proactive Herds Are Doing Right Now

Across the country, dairy producers aren’t waiting for Washington to reach consensus. Here’s what the smartest operators are doing:

Building Documentation Systems: Smart operators are logging every dime—not just for taxes, but for the inevitable indemnity fights. Production impacts, recovery timelines, breeding disruptions, veterinary costs, overtime hours. If you ever need to show a Congressional office what this actually costs, specific numbers from your own operation are far more compelling than industry averages.

Restructuring Labor: Where possible, larger herds are stopping the “shared worker” loop to cut transmission lines. That’s not feasible for everyone—labor economics are what they are, especially for smaller operations—but farms that can offer consistent full-time hours to keep workers on single operations are reducing one key pathway.

Investing in Early Detection: Daily milk tracking by string is catching drops before clinical signs explode. Farms with strong veterinary relationships are developing monitoring protocols that identify problems early. Close observation of fresh cows—who seem particularly susceptible—and rapid veterinary consultation at the first sign of trouble can reduce outbreak severity even if they can’t prevent infection entirely.

Strengthening Financial Reserves: Producers who’ve watched neighboring operations go through outbreaks are reviewing credit lines, cash positions, and insurance coverage. The farms that weather this best will be those that planned for the possibility before it arrived. That’s not pessimism—it’s the kind of practical risk management that successful dairy operations have always practiced.

Engaging the Policy Conversation: Producer organizations at the state and national levels are amplifying messages to USDA. Individual farmers are contacting Congressional offices. That kind of sustained engagement matters—it reflects dairy constituents making clear that the current pace isn’t acceptable.

Looking Ahead: What to Watch For

Looking ahead, here’s how this might unfold depending on decisions made in the coming months:

If vaccine deployment accelerates and USDA moves forward with conditional approval, transmission could be substantially reduced within six to nine months of deployment. Trade negotiations would need to happen in parallel, but early engagement with trading partners could establish protocols maintaining market access for vaccinated herds. This is the path dairy industry organizations are advocating for.

If the current approach continues with the primary focus on biosecurity and surveillance rather than vaccination, the outbreak will likely continue to expand. Economic losses would keep accumulating. Trade relationships would probably deteriorate further regardless. And the virus would keep circulating—and potentially evolving—in the dairy cattle population.

Regional variation might emerge as a third possibility. Some states might pursue their own approaches more aggressively, creating a patchwork of policies. California’s substantial investments in outbreak response suggest a willingness to act independently. That could accelerate action in some areas while complicating interstate commerce for operations that regularly move cattle across state lines.

Which scenario we end up with depends substantially on decisions made in the next several months. USDA’s next quarterly assessment and any movement on the Medgene conditional license application will be key indicators to watch heading into early 2026.

Scenario | Timeline to Deployment | Additional Herds Affected (Projected) | Cumulative Industry Loss | Key Tradeoff/Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerated approval & deployment | 3-6 months (by June 2026) | +450-650 herds | $1.8-2.4 billion | Requires immediate conditional license; trade protocols negotiated in parallel |

| Current pace (“at least a year”) | 12-18 months (by June 2027) | +1,800-2,400 herds | $4.2-5.8 billion | Continues Sec. Rollins timeline; mounting trade restrictions regardless |

| Extended delay (trade-focused) | 18-24+ months (late 2027+) | +2,800-3,600 herds | $6.5-8.9 billion | Trade restrictions emerging anyway; poultry export rationale weakens as spread continues |

| Regional/state-led patchwork | 6-12 months (varies by state) | +900-1,400 herds | $2.8-3.9 billion | California and other high-density states act independently; creates interstate commerce complications |

| Current baseline (no vaccination) | — | 1,790 herds as of Dec 2025 | $2.1-3.1 billion to date | Using $950-$1,735 per affected cow range × avg herd size ~150 lactating cows × clinical rate ~18% |

Note: Loss estimates use Cornell’s verified $950/cow minimum and true cost range up to $1,735/cow, applied to average affected herd clinical rates of 15-20% with 150-200 lactating cows per operation. Projections assume continued monthly growth rates of 200-350 new herds based on Q3-Q4 2025 trends.

What This Means for Your Operation

Let me pull this together into practical considerations.

On understanding the economics: The verified research shows direct losses of about $950 per clinically affected cow—that’s from the Cornell study published this summer. But because that estimate doesn’t include longer-term reproductive impacts or herd-structure changes, the true cost is likely higher once those factors play out. Budget accordingly.

On biosecurity investments: Enhanced biosecurity reduces risk but can’t eliminate it given current transmission dynamics—and that’s not a criticism of biosecurity, just a realistic assessment of what it can accomplish given the network transmission problem. USDA support helps with upfront costs. Just go in with realistic expectations about what any individual farm can control.

On the vaccine conversation: Products are in advanced regulatory review. Industry organizations are pushing hard for acceleration while trade concerns create cross-pressures. Importantly, trade restrictions are emerging regardless of vaccination policy, which changes the calculus somewhat. Stay engaged with producer organizations tracking this situation, because developments could come quickly once decisions are made.

On protecting your operation now: Document everything with specifics. Maintain strong veterinary relationships focused on early detection. Review your financial reserves and credit availability against realistic outbreak scenarios. And engage your representatives with your own farm’s story—specific examples matter enormously in policy discussions.

The Bottom Line

The H5N1 situation represents one of the most significant challenges American dairy has faced in decades. What’s frustrating for many of us is the sense that solutions exist—vaccines are in development, regulatory pathways are established, the science is reasonably clear—but the gap between what’s possible and what’s actually happening remains wide.

Understanding the full economic picture, the transmission dynamics, and the policy landscape helps you make informed decisions and advocate effectively for practical solutions. That’s what this comes down to: having the information you need to protect your operation and push for the responses this situation demands.

We’ve actually got most of the tools we need. The real question is whether we’ll use them in time. And that’s a question dairy farmers shouldn’t have to answer on their own.

Key Takeaways

- $950/cow is just the beginning. Cornell tracked direct losses over 67 days—breeding setbacks, lost premiums, and genetic value weren’t counted.

- The hidden costs are brutal. Months of depressed production. Quality bonuses gone. High-genomic animals were culled because their quarters dried off. It compounds.

- Biosecurity helps, but can’t solve this. 20% of dairy workers work across multiple farms, creating transmission pathways that no single operation can control.

- Vaccines exist. Approval doesn’t. Medgene’s product is stuck in regulatory review while 1,790 herds across 18 states keep absorbing losses.

- Your playbook: Document every dollar. Build reserves now. Push your reps hard. The tools to fight this exist—demand they get used.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- The Biosecurity Changes That Stuck: What Dairy Producers Say Actually Works (And Pays) – Discover which low-cost protocols (like neighbor coordination and traffic management) are delivering higher ROI than expensive tech, providing a practical roadmap for reducing transmission risk without breaking the bank.

- The Wall of Milk: Making Sense of 2025’s Global Dairy Crunch – Understand the broader economic storm compounding outbreak losses, as global oversupply pushes milk prices down—making the protection of your reserves and production margins more critical than ever.

- The New Math of Dairy Genetics: Why This Balanced Breeding Thing is Finally Clicking – Learn strategies to build a more resilient herd through multi-trait selection, ensuring your genetic program can withstand health challenges and recover faster when setbacks occur.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!