78% conception rate vs 23%. Same herd. Same feed. Same genetics. The difference? How cows handled the first 3 weeks. New research says we’ve been focused on the wrong thing.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: For 40 years, we’ve assumed fresh cows get sick because their immune systems fail at calving. Iowa State research published in the Journal of Dairy Science (2024) says we’ve had it backwards—early lactation cows actually mount stronger inflammatory responses than mid-lactation animals. They’re not failing; they’re firefighting against bacterial overload when physical barriers are down. The numbers make this personal: metritis costs $511 per case ($23,000 annually on a 300-cow herd at 15% incidence), and University of Wisconsin data reveals a 55-percentage-point fertility gap—78% conception for cows gaining condition in the first three weeks versus 23% for those losing it, same herds, same ration. If the science is shifting, maybe the priorities in the barn should too. Calving hygiene and metabolic support may outperform immune boosters, and the ROI math increasingly favors operations willing to rethink their protocols.

There’s a conversation happening in transition cow circles that I think deserves more attention from producers.

It started for me when I was visiting a 650-cow freestall operation in central Wisconsin last spring. Good herd, solid management team, well-designed protocols. They had quality minerals dialed in, yeast culture in their close-up ration, and attentive fresh cow monitoring. Yet their metritis rates wouldn’t budge below 17–18%.

“We’re doing everything right,” the herd manager told me, genuinely puzzled. “At least everything we’ve been taught.”

That conversation stuck with me because it echoes what I’ve heard from producers across the Midwest and Northeast over the past couple of years. And it turns out, researchers have been wrestling with similar questions—except they’ve been digging into some foundational assumptions that have shaped transition cow thinking for decades.

💡 THE BOTTOM LINE: New whole-animal research suggests fresh cows mount stronger immune responses than mid-lactation cows—not weaker ones. The diseases we see may result from pathogen exposure overwhelming the system, not immune failure.

The Framework We’ve All Learned

If you’ve been in the dairy business for any length of time, you know the standard story about fresh cows: they experience immune suppression around calving, leaving them vulnerable to mastitis, metritis, and metabolic challenges. This framework has shaped ration formulation, supplement choices, and management protocols across the industry since the 1980s.

The science behind it seemed solid. Researchers would draw blood from transition cows, isolate immune cells—particularly neutrophils—and test how those cells performed in laboratory settings. Fresh cow cells consistently showed reduced activity: weaker oxidative burst, fewer surface markers, diminished killing capacity.

But here’s where it gets interesting.

When Dr. Lance Baumgard’s team at Iowa State decided to test immune function differently, they got a very different picture. Baumgard—he holds the Norman Jacobson Professorship in Nutritional Physiology there—challenged whole cows with lipopolysaccharide (a bacterial component that triggers systemic immune response) and compared early lactation animals to mid-lactation animals.

The results, published in the Journal of Dairy Science in 2024, raised some eyebrows.

In a study of 23 multiparous Holsteins, early lactation cows mounted significantly stronger inflammatory responses across virtually every measure:

| Immune Parameter | Early Lactation | Mid-Lactation | Difference |

| Fever Response | +2.3°C | +1.3°C | +1.0°C higher |

| TNF-α (inflammatory marker) | 6.3× elevated | baseline | 6.3-fold higher |

| IL-6 (inflammatory marker) | 4.8× elevated | baseline | 4.8-fold higher |

| Haptoglobin | elevated | baseline | 79% higher |

| LPS-binding protein | elevated | baseline | 85% higher |

Those aren’t the signatures of a suppressed immune system. If anything, they suggest early lactation cows are running hotter immunologically, not cooler.

“Early lactation cows mounted significantly more robust inflammatory responses than mid-lactation cows across virtually every parameter we measured.” — Dr. Lance Baumgard, Norman Jacobson Professor of Nutritional Physiology, Iowa State University

Understanding the Discrepancy

So why did decades of lab studies show one thing while whole-animal challenges show something different? This is worth understanding because it shapes how we think about intervention strategies.

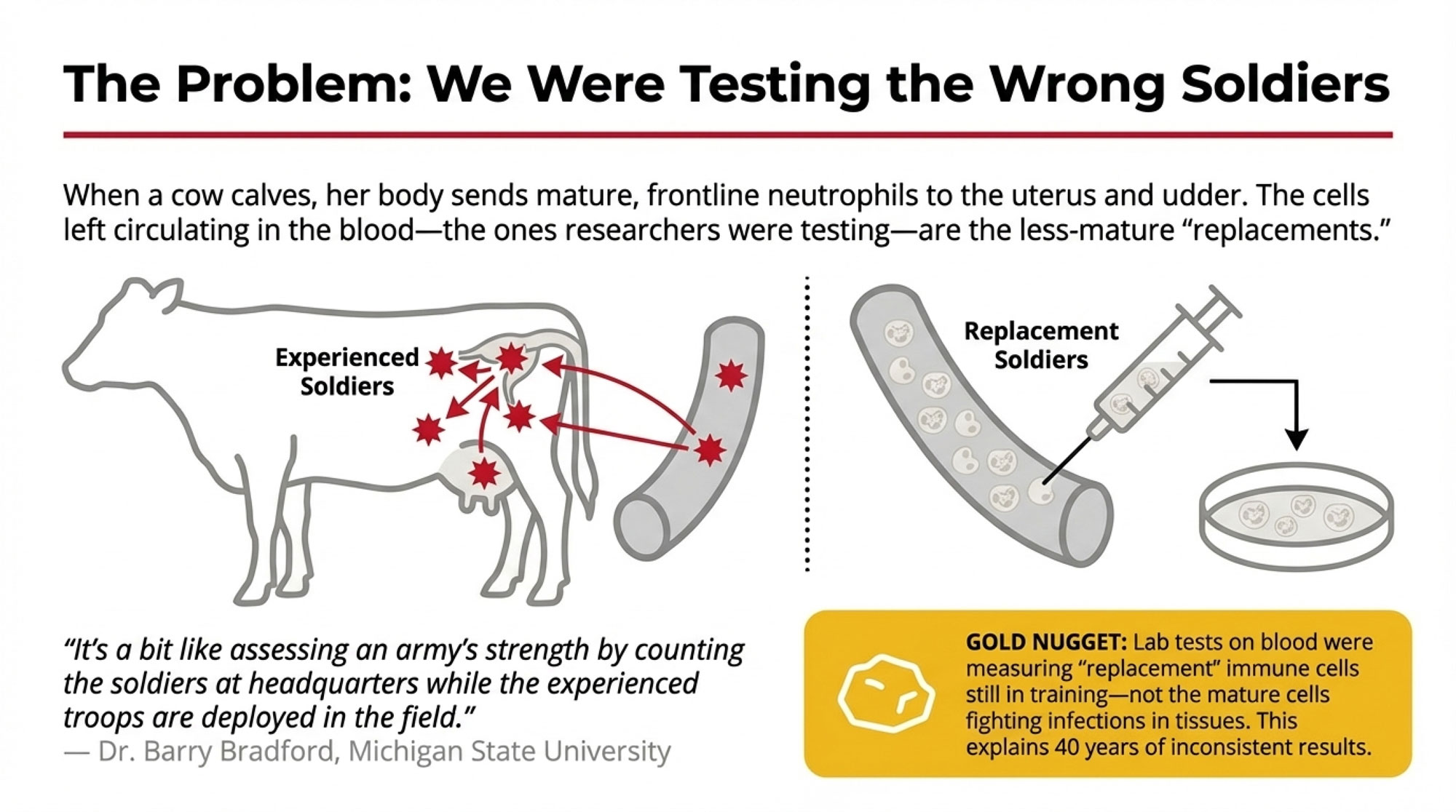

When a cow calves, her body mobilizes mature, fully-equipped neutrophils to the sites that need them most—the uterus recovering from calving, the mammary gland transitioning into lactation. These experienced immune cells deploy to the tissues where pathogens are most likely to gain entry.

To replace them in circulation, the bone marrow releases newer neutrophils that are still maturing. When researchers drew blood and tested circulating cells, they were essentially evaluating replacements rather than frontline defenders.

Dr. Barry Bradford at Michigan State has pointed out that ex vivo testing captures what’s circulating in the bloodstream rather than what’s happening at actual infection sites. It’s a bit like assessing an army’s strength by counting the soldiers at headquarters while the experienced troops are deployed in the field.

💡 GOLD NUGGET: Lab tests on blood samples were measuring “replacement” immune cells still in training—not the mature cells actually fighting infections in tissues. That’s why results were so inconsistent for 40 years.

If Not Immune Suppression, Then What?

This is the practical question, and I think the answer has real implications for how we approach fresh cow management.

The research points to three factors that drive early lactation disease—none of which involve a weakened immune system.

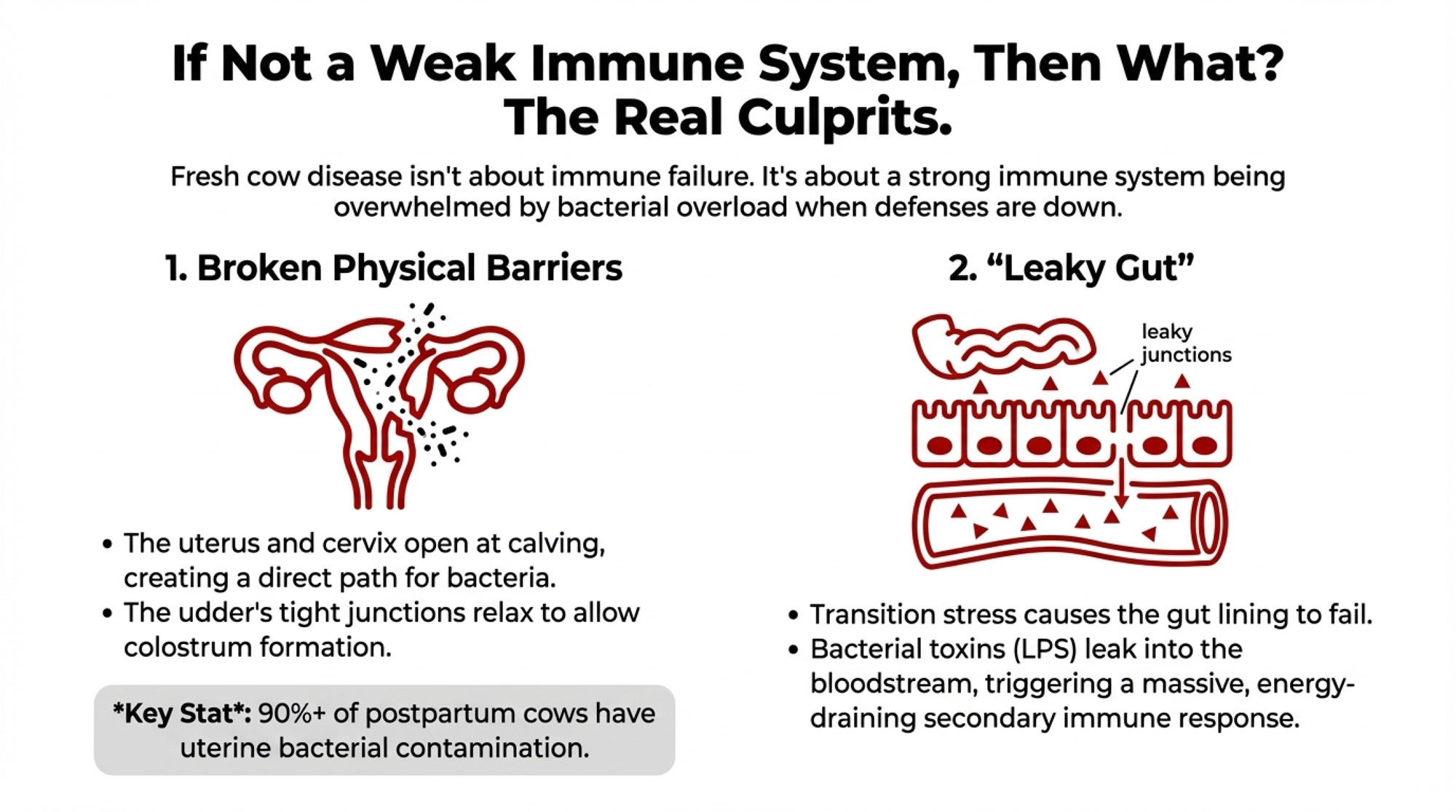

Physical Barriers Are Compromised

Calving opens the reproductive tract, creating opportunities for bacterial invasion. The cervix dilates, tissues experience trauma, and in retained placenta cases, damaged membranes remain attached to the uterine wall. Meanwhile, the mammary gland relaxes its tight junctions to allow immunoglobulins to enter colostrum.

Work from the University of Florida has documented that bacterial contamination of the uterus occurs in the vast majority of postpartum cows—90% or higher, within the first two weeks. Most cows clear this contamination without developing clinical disease. The difference between cows that stay healthy and those that develop metritis often comes down to bacterial load exceeding the clearing capacity, not immune failure.

The Barrier You Don’t See—Gut Integrity

While we often focus on the reproductive tract and the udder, there’s a third barrier that can fail during transition: the intestinal lining.

Several research groups have shown that high-grain diets, transition-period stress, and reduced feed intake can disrupt the “tight junctions” in a cow’s gut. When those junctions loosen, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and other bacterial toxins leak from the digestive tract directly into the bloodstream. If you’ve ever dealt with subacute ruminal acidosis, rapid ration changes, or slug feeding in your close-up or fresh pens, you’ve likely seen some version of this—cows that look “off” without an obvious infection, running low-grade fevers, or just not transitioning the way they should.

Why this matters: This creates a secondary inflammatory response on top of whatever’s happening in the uterus or udder. The cow’s immune system is now firefighting toxins entering through her gut and dealing with bacterial challenges at calving. That dual burden consumes enormous amounts of glucose—energy that should be going toward milk production and tissue repair—further deepening her metabolic deficit and extending her negative energy balance.

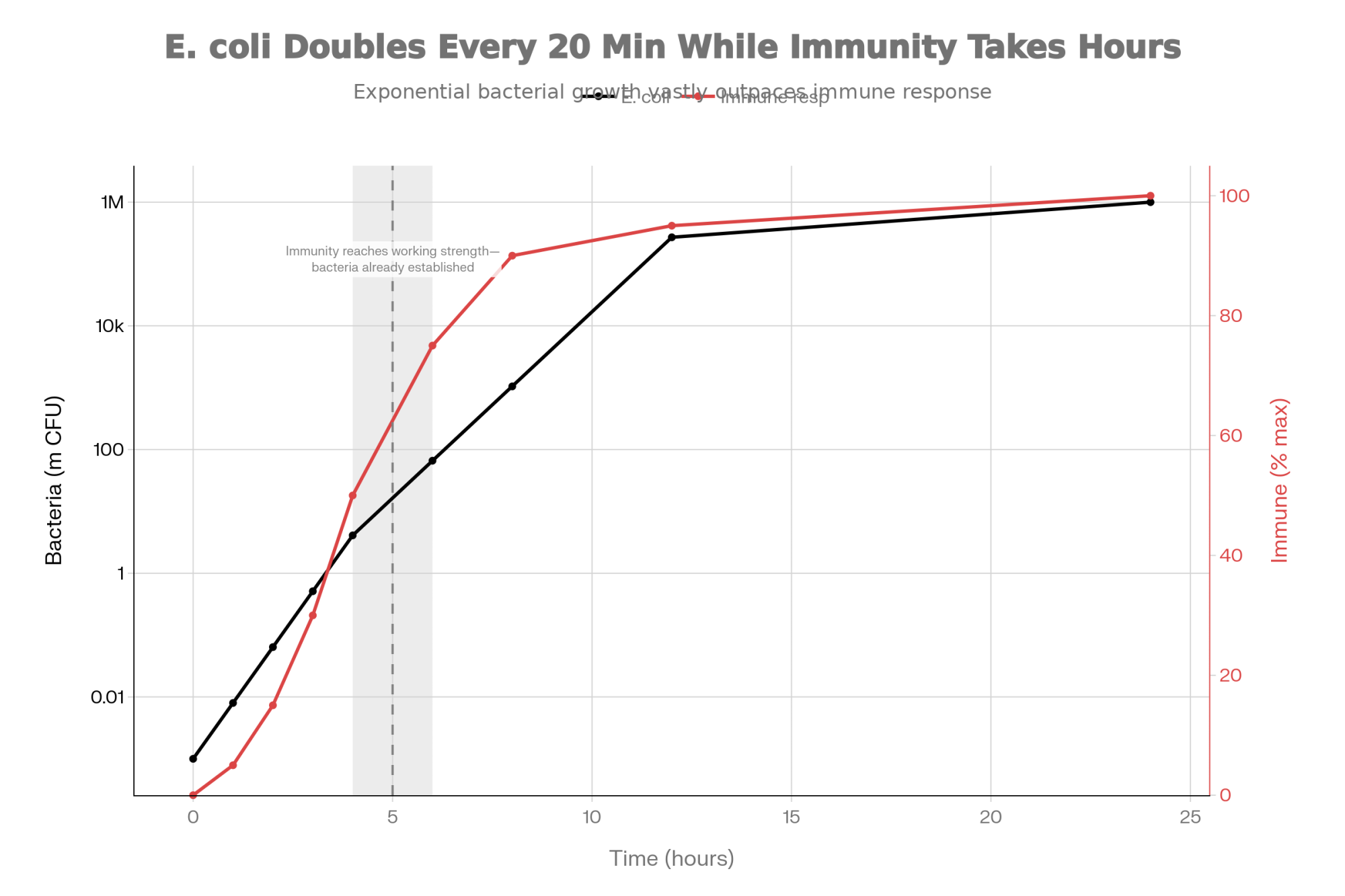

Pathogen Dynamics Work Against Us

The math here is sobering. E. coli can double its population roughly every 20 minutes under favorable conditions. A small initial contamination can reach tens of millions of colony-forming units within 48 hours. Even a robust immune response is racing against exponential bacterial growth.

Virulence factors matter too. Research has identified specific gene combinations in E. coli—particularly kpsMTII and fimH—that correlate with more severe clinical outcomes. It’s not just bacterial numbers; it’s which strains gain entry.

Timing Creates a Gap

Mounting a full inflammatory response takes hours to reach peak intensity. During that ramp-up, bacteria multiply and establish themselves. By the time the immune system hits full stride, significant tissue damage may already have occurred.

| Time (hours) | E. coli Population (million CFU) | Immune Response Intensity (% max) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.001 | 0 |

| 1 | 0.008 | 5 |

| 2 | 0.064 | 15 |

| 3 | 0.512 | 30 |

| 4 | 4.1 | 50 |

| 6 | 66 | 75 |

| 8 | 1,050 | 90 |

| 12 | 270,000 | 95 |

| 24 | >1,000,000 | 100 |

This timing mismatch explains why early lactation infections often present with greater clinical severity. The immune response isn’t weaker—it’s just working from behind the scenes.

💡 THE BOTTOM LINE: Fresh cow disease isn’t about weak immunity. It’s about: (1) physical barriers being down, (2) bacteria multiplying faster than the immune response can ramp up, and (3) which bacterial strains get in.

The Reproductive Connection

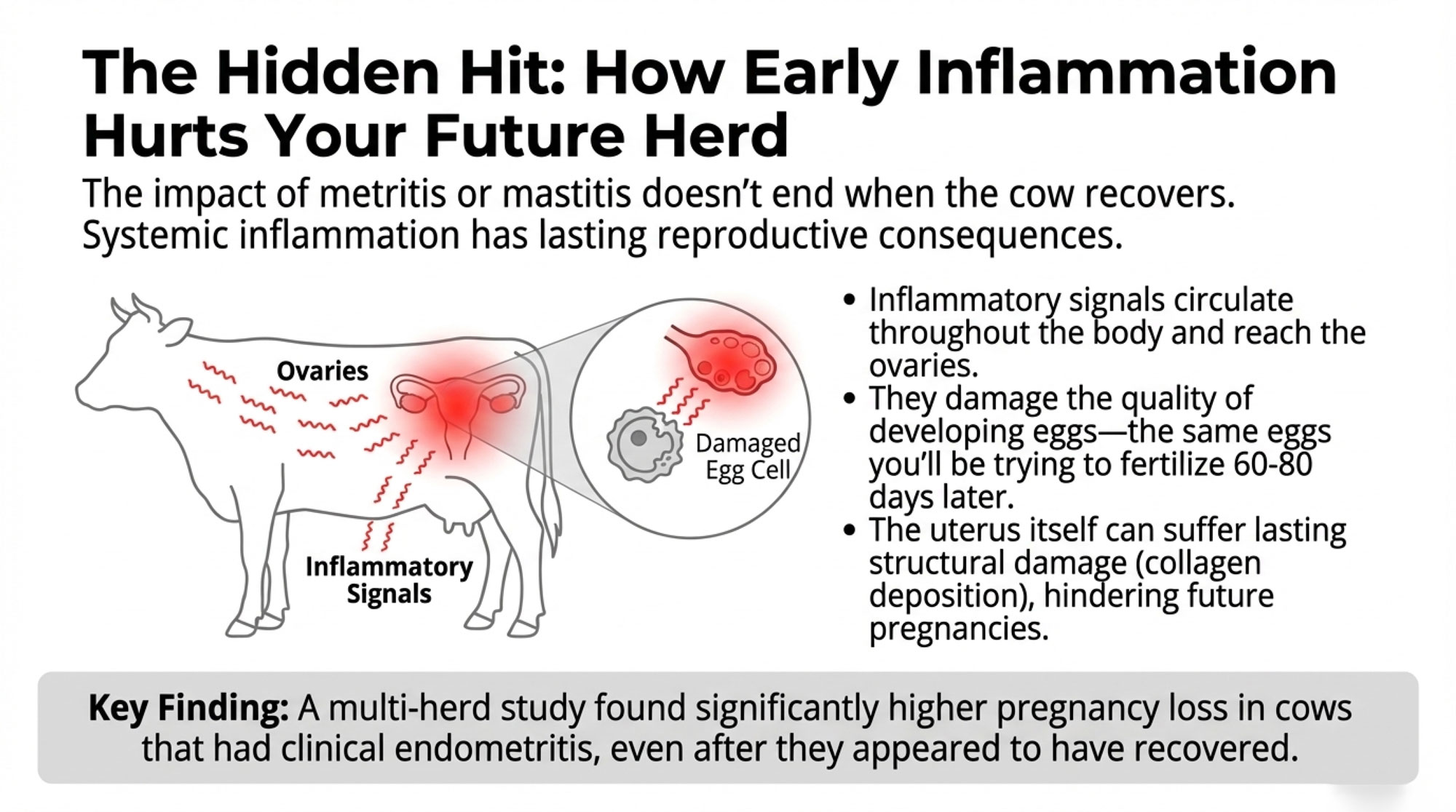

What’s received less attention, but may matter more economically, is how early lactation inflammation affects fertility weeks or months down the road.

When mastitis or metritis triggers systemic inflammation, those inflammatory mediators circulate throughout the body—including to the ovaries. Research has shown that pro-inflammatory cytokines alter gene expression in granulosa cells, the supportive cells surrounding developing oocytes.

Here’s what that means practically: the eggs you’re targeting at breeding time (60-80 days in milk) began their final development phase weeks earlier. If they developed during a period of systemic inflammation, their quality may be compromised before you ever breed that cow.

A multi-herd study from Argentina tracking over 1,300 lactations found significantly higher pregnancy loss rates in cows that experienced clinical endometritis—even after apparent recovery. These animals conceived but couldn’t maintain pregnancies at normal rates.

Work by researchers at Ghent University in Belgium has documented lasting structural changes in the uterus following metritis—increased collagen deposition and altered tissue architecture—that persist long after clinical signs resolve. This helps explain why treating acute disease doesn’t always translate to improved reproductive outcomes. Antibiotics can clear the infection, but they can’t reverse cellular-level changes that have already occurred.

The Data That Should Change How You Think About Transition Cows

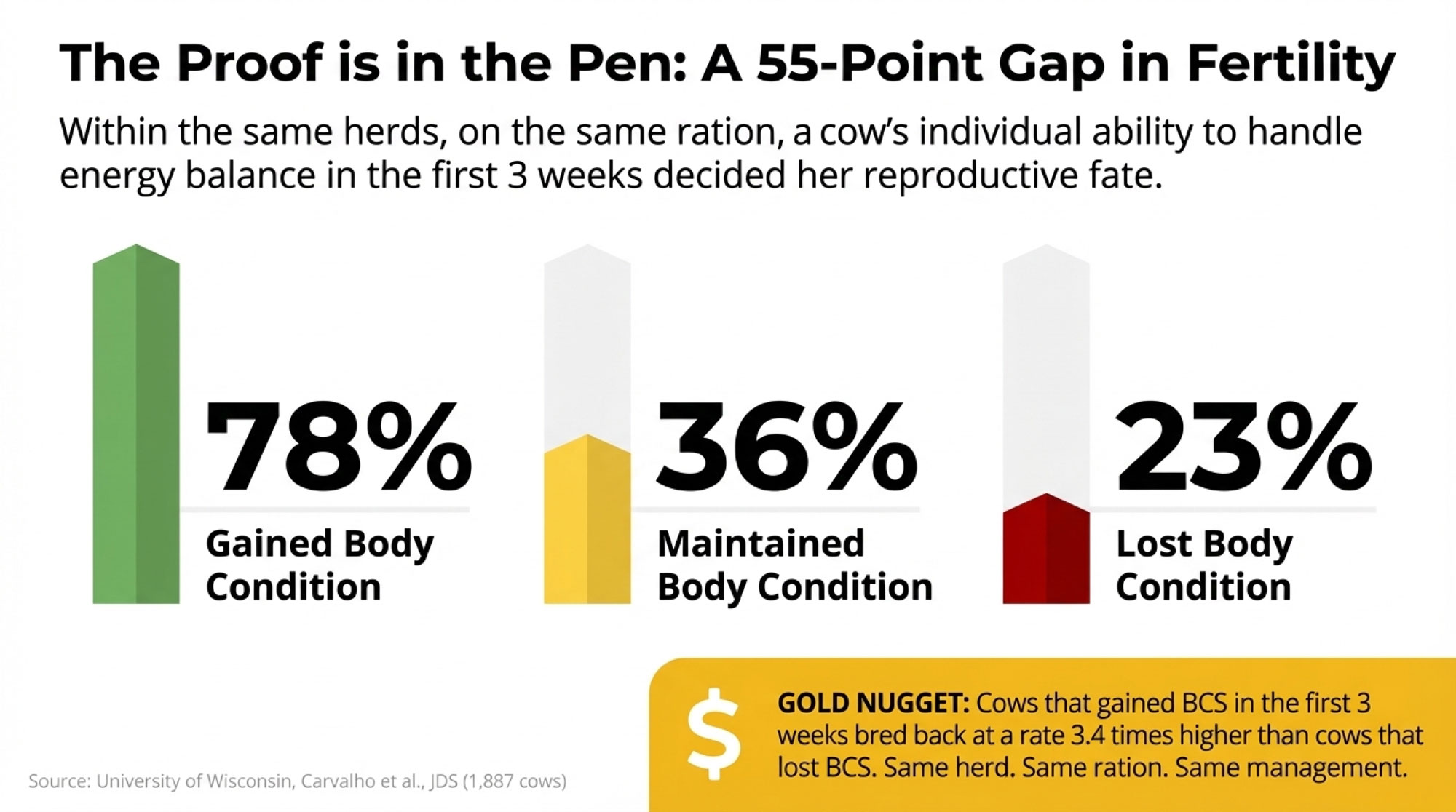

One of the more striking findings I’ve come across involves how differently individual cows handle the transition period—even within the same herd, on the same ration, under identical management.

Research from the University of Wisconsin, published by Carvalho and colleagues in the Journal of Dairy Science, tracked body condition changes in 1,887 early-lactation cows. The fertility differences based on energy balance in those first three weeks were staggering:

Body Condition Change vs. Conception Rate (n=1,887 cows)

| BCS Change (First 3 Weeks) | Number of Cows | Conception Rate | Relative Performance |

| Gained condition | 423 | 78% | Baseline |

| Maintained condition | 675 | 36% | -54% vs. gainers |

| Lost condition | 789 | 23% | -70% vs. gainers |

Read that again. Same herds. Same management. Same genetics, largely. Same nutrition program. But individual metabolic capacity varied so dramatically that fertility outcomes ranged from 23% to 78%—a 55-percentage-point gap based on how cows handled energy balance in the first three weeks.

💡 GOLD NUGGET: Cows that gained BCS in the first 3 weeks bred back at 78%. Cows that lost BCS? Just 23%. That’s a 3.4× difference in fertility—from the same herd, same ration, same management.

What strikes me about this data is what it suggests about blanket protocols. If some of your cows are cruising through transition while others are metabolically struggling, uniform interventions are going to miss in both directions.

This is where precision monitoring technologies—rumination collars, activity sensors, temperature monitoring—start to make more sense. Cornell University research has demonstrated that automated systems can flag at-risk cows several days before clinical signs appear. Healthy cows typically ruminate 460-520 minutes daily, and meaningful deviations from that baseline often signal trouble before visual observation catches it.

Regional and Seasonal Considerations

It’s worth noting that these dynamics may play out differently depending on where you’re farming and what time of year your cows are calving.

For operations in the Southeast, Southwest, or anywhere summer heat is a significant factor, heat stress during the dry period and early lactation compounds the metabolic challenges fresh cows already face. The same barrier vulnerabilities exist, but cows dealing with heat stress are simultaneously managing additional metabolic strain—which may explain why some operations see seasonal spikes in transition problems that don’t respond to the same interventions that work in cooler months.

Production system matters too. Confinement operations with higher cow density face different pathogen pressure dynamics than seasonal grazing systems where cows calve on pasture. The barrier vulnerability is identical, but exposure levels and bacterial populations differ. A protocol that works beautifully on a Wisconsin freestall dairy may need adjustment for a grass-based operation in Vermont or a large dry-lot facility in California’s Central Valley.

| Production System | Primary Risk Factor | Metritis Incidence | Peak Risk Period | Priority Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confinement/Freestall | High pathogen pressure (cow density) | 12-18% | Year-round (worse summer) | Bedding hygiene + individual calving pens |

| Tie-stall | Moderate pressure, close monitoring | 8-14% | Winter (footing issues) | Foothold safety + rapid detection |

| Seasonal grazing | Low pressure, clean pasture calving | 5-10% | Spring (mud/weather) | Pasture rotation + shelter |

| Heat stress regions (SE/SW) | Metabolic + immune compromise | 15-22% | May-September | Cooling systems + dry period heat abatement |

What This Means for Your Operation

So where does this leave us? A few priorities emerge from the research, though I’d be the first to acknowledge that implementation looks different in a 200-cow tie-stall operation in Pennsylvania than in a 5,000-cow facility in the Central Valley.

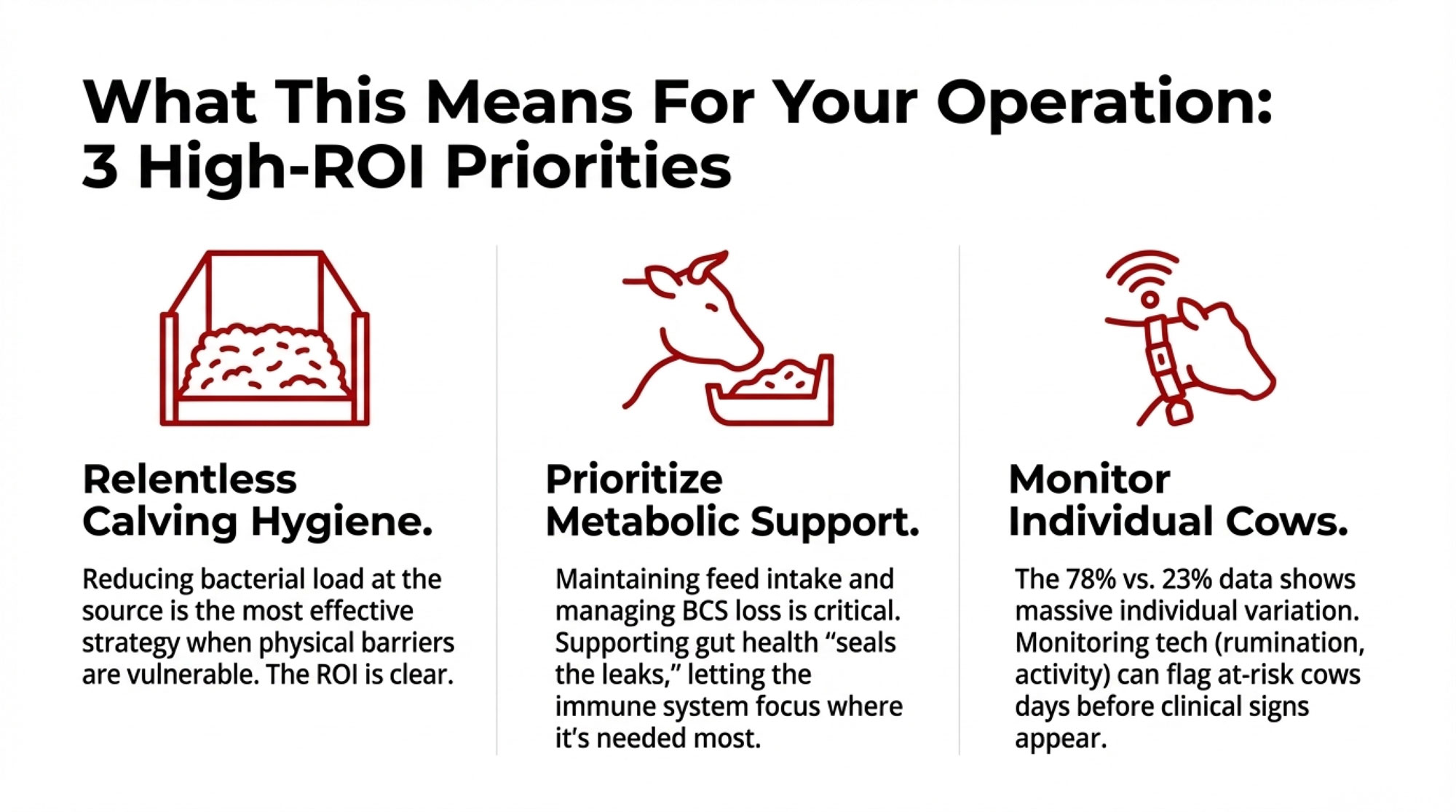

Calving Hygiene: The ROI Is Better Than You Think

If disease susceptibility stems from pathogen exposure during barrier vulnerability rather than immune suppression, then reducing bacterial load at calving becomes paramount.

The practices themselves aren’t new: individual calving spaces where feasible, fresh bedding for each cow, rigorous equipment sanitation, and adequate rest time between animals using the same pen. The research sharpens the economic justification for these investments.

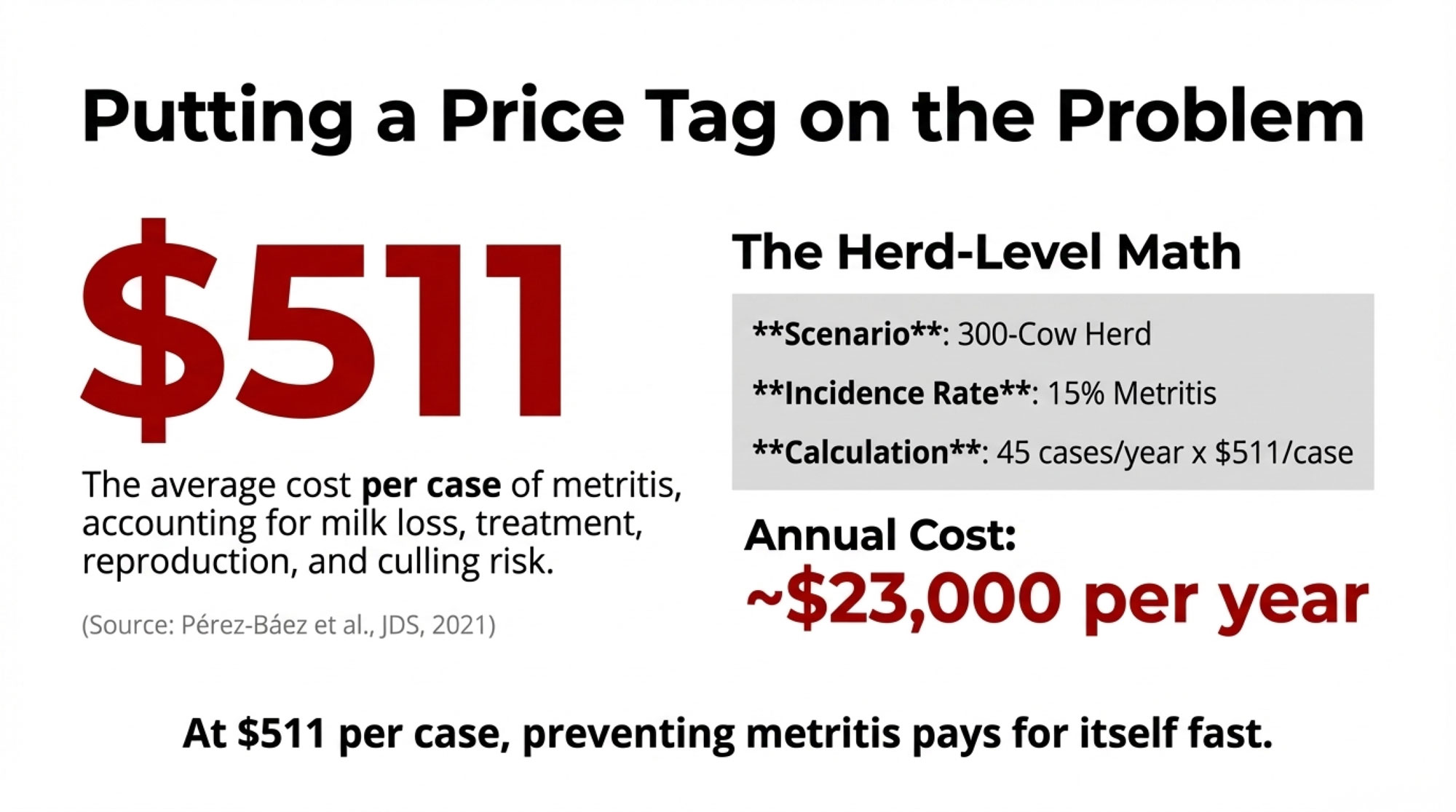

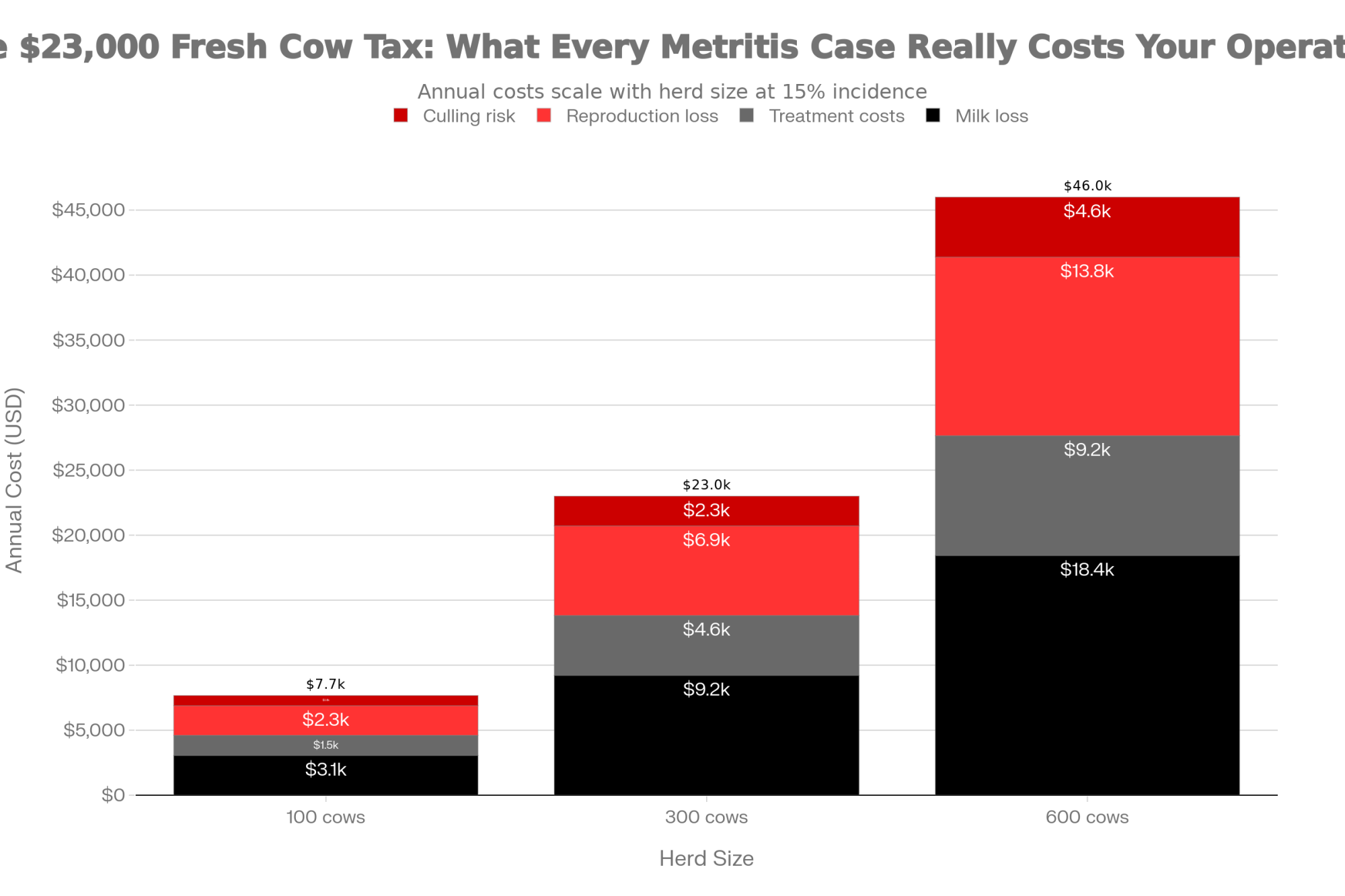

A 2021 analysis by Pérez-Báez and colleagues, published in the Journal of Dairy Science, examined metritis costs across 16 U.S. dairy herds:

| Metritis Cost Factor | Finding |

| Mean cost per case | $511 |

| Cost range (95% of cases) | $240 – $884 |

| Includes | Milk loss, treatment, reproduction, and culling risk |

On a 300-cow herd running 15% metritis incidence, you’re looking at 45 cases annually—somewhere in the neighborhood of $23,000 in direct costs before accounting for the fertility tail.

💡 THE BOTTOM LINE: At $511 per case average, metritis is costing a 300-cow herd with 15% incidence roughly $23,000/year. Cutting that rate in half through better calving hygiene pays for itself fast.

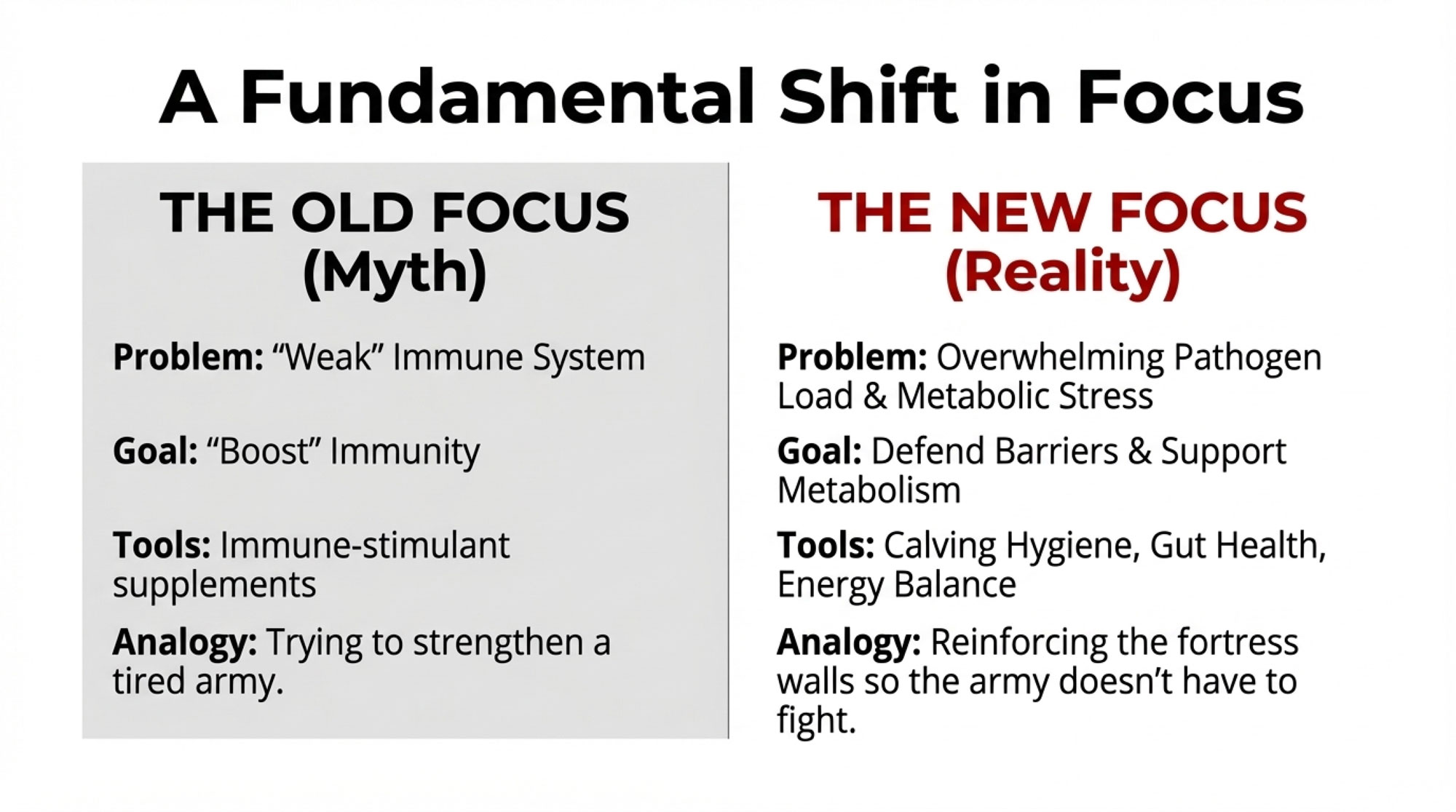

Metabolic Support May Matter More Than Immune Boosting

This is where some of the research becomes practically relevant. If the issue isn’t immune suppression, then products marketed primarily for “immune support” may be addressing the wrong problem.

I want to be careful here, because I know plenty of operations report good results with their current transition protocols, including various immune-targeted supplements. Individual variation means some interventions may genuinely help certain cows even if the mechanism isn’t exactly what we thought. And controlled research doesn’t always capture the complexity of commercial conditions.

When we talk about metabolic support, we aren’t just talking about energy—we’re talking about barrier integrity. Some research groups are testing gut-focused tools to help stabilize that intestinal lining during transition. For example, work on Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation products (SCFP)—the yeast-based additives many producers already use—suggests they may help maintain tight junction integrity and reduce the inflammatory load from gut-derived endotoxins. Other trials are looking at specific trace mineral forms (like organic zinc or chromium) that support both gut barrier function and glucose metabolism during immune challenges.

These are still being tested and tuned on real farms, but the logic behind them fits what we’re seeing: if you can reduce the “noise” from gut-derived inflammation, the cow’s immune system can focus its resources where they’re needed most—the mammary gland and uterus.

That said, what the research points to is that interventions supporting metabolic function—maintaining feed intake, managing body condition loss, and smoothing dietary transitions—address what the data actually shows is happening.

| Intervention Strategy | Target Mechanism | Research Support | Cost per Cow | Expected ROI | Priority Tier |

| Calving hygiene upgrade | Reduces bacterial exposure | Strong (observational) | $8-15 | 3-5× return | Tier 1: Essential |

| Automated health monitoring | Early detection (rumination/activity) | Strong (controlled) | $150-200/yr | 2-4× return | Tier 1: Essential (>200 cows) |

| Metabolic support protocols | Maintains intake, reduces BCS loss | Strong (mechanistic) | $25-40 | 2-3× return | Tier 1: Essential |

| Omega-3 (EPA/DHA) | Inflammation resolution | Moderate (variable) | $35-60 | 1.5-2× return | Tier 2: Consider (high inflammation) |

| Generic immune boosters | Uncertain—wrong problem? | Weak (conflicting) | $40-80 | 0.5-1.2× (uncertain) | Tier 3: Reevaluate |

Dr. Tom Overton at Cornell has emphasized for years that the transition period is fundamentally about managing competing demands for nutrients. The cow is simultaneously supporting immune function, ramping up milk production, and attempting tissue repair—all while she can’t eat enough to cover the energy requirements. Anything that improves intake or metabolic efficiency during this window has cascading benefits.

Inflammation Resolution Is Worth Watching

This is still an emerging area, but early results are worth watching. Omega-3 fatty acids—EPA and DHA from fish oil or algae sources—serve as precursors for what researchers call specialized pro-resolving mediators. These molecules don’t suppress inflammation; they help complete the inflammatory process efficiently, signaling the body to transition from active response into tissue repair.

Earlier work from the University of Florida documented reduced systemic inflammation and modest improvements in reproduction in cows receiving omega-3 supplementation during the periparturient period. Results across subsequent studies have varied with product and dosing, but the biological rationale is sound.

Keeping Perspective

I should acknowledge that this isn’t a settled conversation. Some nutritionists and veterinarians I respect point out that their transition protocols—including products I’ve just suggested—produce consistently good outcomes in client herds. They’re not wrong to trust their experience.

Science advances incrementally. There’s often a gap between what controlled research demonstrates and what works in the messy reality of commercial dairy production. Individual farms vary in pathogen pressure, facility design, genetic base, and management execution. What struggles on one operation may succeed on another for reasons that aren’t immediately apparent.

The value of the emerging research isn’t that it invalidates decades of transition cow wisdom. It’s that it offers a more refined framework for understanding why things work when they do—and for asking better questions when outcomes don’t match expectations.

💡 GOLD NUGGET: The goal isn’t to throw out what’s working. It’s to understand why it works—so you can troubleshoot when it doesn’t.

Three Questions to Ask Your Advisory Team

1. What’s the mechanism? When evaluating any product or protocol, understanding how it’s supposed to work—and whether that mechanism aligns with current understanding—helps separate substance from marketing.

2. How will we measure it? Peer-reviewed research is valuable, but on-farm data from your own herd is more valuable still. If you’re implementing changes, rigorously tracking outcomes actually to know whether they’re helping makes the investment worthwhile.

3. What’s our baseline? Improvement requires knowing where you started. What’s your current metritis rate? Retained placenta incidence? First-service conception rate? These benchmarks make evaluation possible.

The Bottom Line

That Wisconsin freestall operation I mentioned at the start? They eventually brought metritis rates down to single digits—roughly half of where they’d been. The changes that moved the needle weren’t primarily nutritional. They redesigned their calving area, got more rigorous about bedding management, and started using rumination monitoring to flag individual cows showing early warning signs.

Their experience won’t map directly onto every operation. But the underlying approach—reduce exposure, support metabolism, monitor individuals—aligns with where the science seems to be heading.

The conversation around transition cow immunity will continue to evolve. What seems increasingly clear is that the “immune suppression” framework doesn’t fully capture what’s happening. Fresh cows aren’t defenseless; they’re mounting robust inflammatory responses while simultaneously managing enormous metabolic demands. The diseases we see are more likely to result from overwhelming pathogen exposure during barrier vulnerability than from an immune system that’s shut down.

For producers, that shifts focus toward controllable factors: calving environment hygiene, metabolic support strategies, and individual animal monitoring. These aren’t dramatic interventions. They don’t come with splashy marketing. But they address the mechanisms that current research actually supports.

And sometimes, that’s exactly what progress looks like.

Key Takeaways

The emerging picture:

- Early lactation cows mount robust—even heightened—immune responses, not suppressed ones

- Fresh cow disease results from overwhelming pathogen exposure during barrier vulnerability, combined with metabolic stress

- Early lactation inflammation creates downstream reproductive effects that persist for months

- Individual variation is massive: BCS gainers bred at 78%, BCS losers at just 23%

Practical priorities:

- Calving hygiene delivers serious ROI—metritis costs average $511/case

- Metabolic support (feed intake, BCS management) addresses mechanisms that the research supports

- Individual cow monitoring catches problems before clinical signs appear

- Regional factors influence how these principles apply on your operation

Questions for your team:

- What mechanism does this intervention actually address?

- How will we track whether changes are improving outcomes?

- Are we capturing enough individual cow data to spot the variation in our herd?

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The First 48 Hours: A Manager’s Guide to Fresh Cow Success – Reveals a streamlined management audit to sharpen your fresh cow checks. You’ll gain a high-impact strategy for prioritizing labor where it generates the most ROI, drastically reducing the clinical metritis cases that drain your bottom line.

- Dairy Economics 2025: The Hidden Cost of Inflammation – Exposes the massive financial drag caused by sub-clinical inflammation. This analysis arms you with the long-term economic strategy needed to shift your focus from treatment to prevention, securing a competitive advantage and a more resilient balance sheet.

- Genetic Selection for Resilience: Breeding the Cow of the Future – Breaks down how to leverage the newest genetic health traits to bake-in resilience from day one. You’ll gain the insight needed to stop breeding for “milk-only” and start creating a self-sufficient herd that naturally handles the metabolic stress of transition.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!