Judge the cow in front of you—not the crowd. Internationally renowned Judge Callum McKinven shares his no-nonsense ringcraft for young judges: move, see, decide, explain.

You know that feeling when you watch a master at work? That’s what happened in Ecuador this year when Callum McKinven stood in front of a room full of judges—some with decades under their belts, others just getting started. He was 19 when he walked into his first ring, with show organizers expecting a 40-year-old man. Fast-forward four decades and 32 countries later, and here’s what strikes me about his approach: it’s deceptively simple, brutally honest, and absolutely revolutionary in how it cuts through the politics that can poison a show ring.

The thing about confidence—real confidence—is that it’s not some mystical quality you’re born with. McKinven teaches that it’s discipline. Pure and simple. And after watching his system work everywhere from the formal protocols of English shows to the warm hospitality of South American venues, I can tell you this much: the industry’s top judge doesn’t drift around looking for approval from the bleachers. He doesn’t give past champions a free ride because they’ve been winning. And he certainly doesn’t stand there fumbling through memorized speeches when it’s time to give reasons.

What you’re getting here isn’t theory—it’s McKinven’s working playbook from that Ecuador clinic, the kind of stuff you can actually use this weekend at your county fair. Pre-show discipline that prevents public mistakes. Ringcraft that builds exhibitor trust instead of destroying it. His evaluation pattern that keeps you consistent whether you’re judging five animals or fifty. The reasons strategy that wins respect instead of starting arguments. His youth-class approach that actually builds the next generation. And yes… the ethics that let you sleep well on the plane home afterward.

Here’s the quiet part we’re saying out loud: the crowd isn’t your boss. McKinven proved it. Now let’s see how he does it.

“The farther back you are, the better you can see them,” McKinven teaches. Keep that in your back pocket. Trust me, we’ll circle back to it.

Show Up Ready, Not Lucky—Because Reputation Travels Faster Than Luggage

Look, we’ve all been there. You get the call to judge, say yes, then life happens, and suddenly you’re scrambling. McKinven’s refreshingly honest about this—he jokes that his wife is the only reason he makes it to shows because she’s the organized one who actually writes dates down. But here’s his non-negotiable fix, and I’ve seen too many careers damaged to ignore it: when you accept a judging assignment, write it down immediately. Not tomorrow. Not when you get home. Right then.

Missing shows isn’t an “oops”—it’s unprofessional. And in our industry, where your reputation travels faster than your luggage, you simply can’t afford that kind of mistake.

Here’s what’s interesting, though… most judging problems get solved before the first class walks in. McKinven emphasizes arriving at least 30 minutes early—more if you’re dealing with fairground parking and those gate delays we all know too well. Why? Because early gets you the things that prevent public embarrassment: a quick chat with ring stewards about traffic flow, a walk-through to figure out where you’ll stand for reasons, a mic test so you’re not chasing feedback squeals all day.

The World Dairy Expo Lesson Nobody Talks About

Speaking of embarrassment… McKinven learned about footwear the hard way. Picture this: World Dairy Expo, two breeds, 900 head to judge. He shows up in brand new shoes. By the end of the day, his wife had to pull those blister-inducing shoes off his feet. Now he tells everyone: “Wear something that looks proper but feels comfortable—you’re not going to be thinking about the animals if your feet are killing you.”

That story gets a laugh at clinics, but there’s a deeper point to it. The details matter. Dress like the judge—not because you need to wear suits in a stockyard, but because you need to be easily recognizable. McKinven’s judged everywhere from formal English shows (a tie is required) to relaxed South American venues, and the principle remains the same. Look the part. Look prepared.

The confidence piece? McKinven stresses being “confident but friendly”—especially with youth classes. Smile. Say good morning. Lower the temperature in the ring. You’re not the sheriff; you’re setting the standard. There’s a difference, and exhibitors feel it immediately.

“You want to be confident but don’t look cocky. Be yourself with the people, be nice with the people in the ring. Don’t give the impression that you’re this scary guy.” —Callum McKinven

Keep the Ring Moving, Keep the Trust—Why Speed Is Everything

Here’s something McKinven learned from over 40 years in the ring that never fails: taking too long causes exhibitors to lose confidence in your process. Go too fast, and they won’t believe you actually looked. Finding that sweet spot is what separates good judges from great ones.

I remember McKinven telling the Ecuador group about his first show—36 animals in his class while an experienced judge in the next ring was still sorting five. He was done giving reasons while the other guy’s animals were still circling. Maybe he went too fast that day, but here’s what he figured out: scratching your head or hesitating reads like uncertainty to exhibitors, and uncertainty makes everything harder, especially when it’s time to give reasons.

What’s fascinating about McKinven’s distance approach is how simple it is. Start wide. The farther back you stand when animals enter, the better you’ll see balance, flow, and obvious outliers. It’s not dramatic—just effective. And this is crucial: let them move. Big classes are impossible to judge fairly if you don’t get motion, and McKinven insists on this.

The Ring Flow Reality Check

Here’s McKinven’s system broken down by class size—and this comes straight from watching him work:

Small class (5-10 animals)? Stand back and see them all. Sort decisively. No head-scratching. Keep reasons tight—three traits, done.

Medium class (10-20)? Get your top three or four in mind early, then work methodically without losing the rest. Create space to watch movement. Double-check borderline calls with one more circle.

Large class (20-30+)? This is where it gets tricky. Pre-plan traffic with the ring crew. Stage the first sort fast. Insist on motion—every animal needs to be seen moving at least once. Find the obvious last if it’s truly obvious, but don’t force it.

Point clearly when you pull. McKinven can’t stress this enough. If your gesture is vague, two cows step forward, and one shouldn’t be moving. That’s on you. And when you do miscue—because we all do—fix it fast and discreetly. Signal the mistaken one to hold without making a scene. The job is placing cows, not embarrassing people.

And here’s McKinven’s cardinal rule that separates him from judges who get caught up in politics: keep your eyes off the stands. It’s amazing how quickly a head shake from someone you respect can mess with your confidence. Don’t look. You’re judging today. You earned that center ring position—use it.

A Pattern You Can Repeat from Wisconsin to Ecuador

What strikes me about great judges—McKinven included—is how predictable their process is. Not their outcomes, but their approach. McKinven maintains a consistent pattern, so exhibitors learn what he values by the end of the day. That consistency builds trust, even when people disagree with individual placings.

I watched him work through this in Ecuador, pointing to a cow and saying, “Look at that chest—that’s a good example of what I want.” He’d already made his first read from distance: balance. Front-to-rear symmetry, nothing top-heavy, nothing sinking behind the shoulders. Then that chest width check. He told the group that he could immediately see whether a cow would do well if everything else held up.

McKinven’s Walk-Through Pattern (The Real Deal)

Here’s exactly how McKinven teaches it, and I’ve seen this work in rings from Ontario to New Zealand:

- Side profile and topline: Length and straightness without stiffness. Dairy neck—long, clean, feminine head. No fuss, no exaggeration.

- Feet and legs: Strong pasterns, good heel depth, tracking true. And here’s what separates McKinven from textbook judges—locomotion under pressure matters. Don’t just stand still and evaluate.

- Rib structure: Spring and drop of the rib, with openness that avoids slab-sidedness. That angular “dairy” character shows up in more than one place—front end, rib, loin.

- Bone quality: Flat bone, clean joints, not coarse. McKinven notes how bone reads under good skin tells you about longevity and efficiency (and yes, we all see more of this with cows on different rations).

- Mammary system: Fore udder blending cleanly into the body wall, rear udder height and width, a clear median suspensory ligament, and square teat placement.

He’ll even note muzzle width as a positive signal for head width and overall strength. It’s one of those details you hear old-timers mention because they’ve watched it correlate with cattle that actually work and last.

The Regional Reality

Here’s the nuance I appreciate about McKinven’s approach—he adapts his lens without changing his standard. In some countries, you won’t see the same depth you’d expect from a North American spring pasture. Feed conditions, heat stress, forage availability… call it what it is. “I still look for the same pattern every country I go to,” McKinven explains, “but if it’s a country where the cows aren’t going to be as deep, I’m making the best of what I see”.

You still run your pattern, but you judge within that day’s reality. That’s dairy farming, not pageantry.

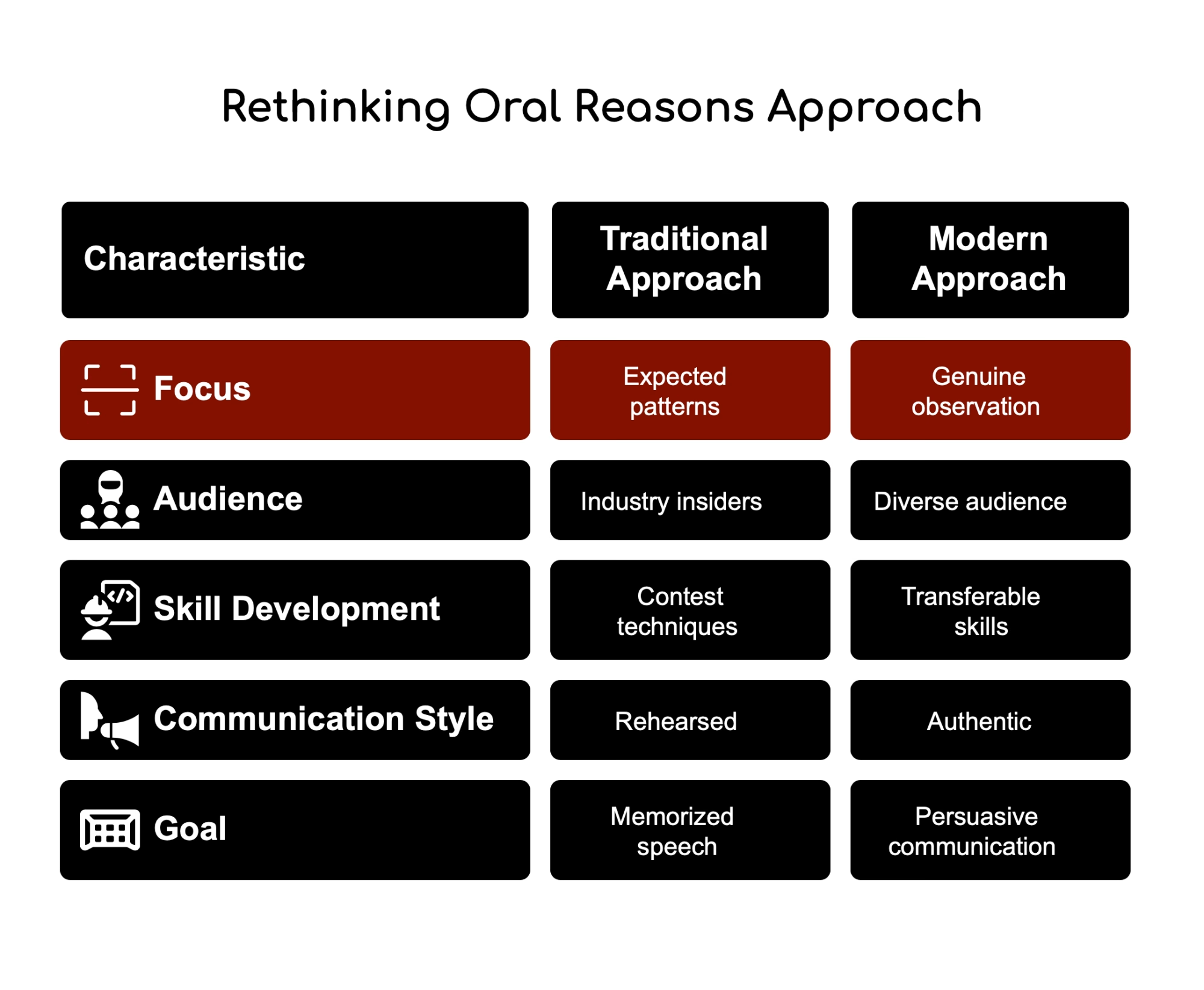

Stop Memorizing, Start Seeing—The Mic Moment That Changes Everything

“Don’t try to memorize your reasons,” McKinven teaches, and this might be the most important sentence in this entire piece. “Your eyes tell you what to say when you judge those animals.” If you’ve ever blanked at the mic—and we all have—you know exactly why he puts it this way. He attempted to memorize early in his career. It backfired completely.

I love this story from his early days: first class, trying to remember his prepared speech, and he’s standing there like, “Oh, these first… six, nothing.” Goes to the mic, trying to remember what he was going to say instead of just looking at what was in front of him.

The fix is deceptively simple: look at what you’re talking about while you talk about it. McKinven insists on this. Your brain and eyes sync under pressure when the animal becomes your teleprompter. “When those animals come out, you’ll know she’s got flatter, nicer bone quality, she’s longer in her neck because she’s got a better fore attachment.”

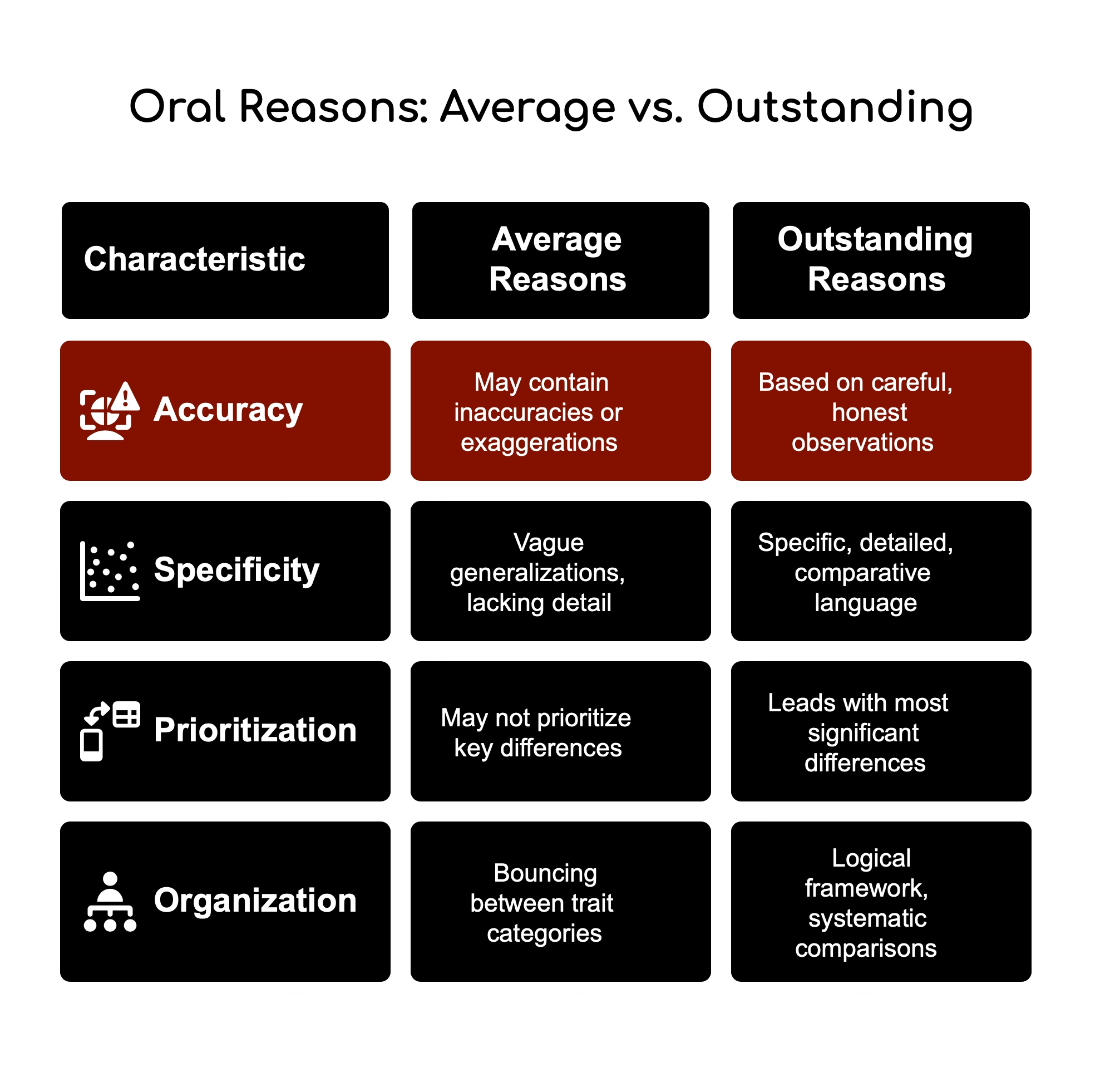

The Language That Actually Works

McKinven’s approach eliminates lazy phrases that teach nobody anything. “Nicer legs” is meaningless. “Stronger pasterns, tracking truer on the turn, with flatter bone quality” is an honest and helpful description. “Better udder” tells exhibitors nothing. “Higher and wider at the rear attachment, stronger cleft, more secure fore udder blend to the body wall” tells them exactly what you valued.

Here’s McKinven’s framework you can steal today—and I mean literally write this down:

Frame it: “I place one over two for her advantage in [trait A], [trait B], and [trait C]…”

Trait bank: rear udder height/width; fore udder blend; teat placement; median suspensory strength; pastern strength; heel depth; tracking; spring and drop of rib; angularity; chest width; neck length; topline

Positive close: “I admire the dairy character of two and recognize her length, but today one carries the advantage in udder attachments and locomotion.”

McKinven keeps it to three reasons per animal. Not ten. Crisp, observable traits—no lengthy explanations. And here’s something he emphasizes that I wish more judges understood: keep it positive even when contrasting. You can acknowledge the second cow—”a very dairy cow” or note “her clean neck”—right before explaining why the first has the advantage.

The exhibitor standing at the bottom deserves to hear something good. They brought an animal, paid entry fees, and helped fill your class.

“You never talk bad about the cows, you talk positively about the cow. I always try to say something positive about every cow.” —Callum McKinven

Youth Classes—Where Futures Get Built or Broken

Walk into a youth class looking like security, and the kids shut down. McKinven’s learned this over four decades of working with young exhibitors. Try a smile and “Good morning.” It’s remarkable how quickly shoulders drop and eye contact returns.

Here’s a moment that stuck with me from the Ecuador clinic: McKinven talking about getting on his knee to talk eye-to-eye with really young kids. “If I see them start to cry, I make sure I say, ‘You did a great job, you could be up the line very easily, it’s just that little thing.’ I judge young people to make sure they don’t cry.”

That’s not going soft—that’s building the industry’s future. A harsh critique tears down a future exhibitor. Constructive guidance builds one up.

The “Bottom Six” Strategy That Changes Everything

For big youth classes—and we’re talking 25+ kids here—McKinven has a specific strategy that every judge should steal. Don’t leave one kid standing last, as if they’re wearing a scarlet letter. This is what he actually says: “Last six, just come on in, just come on in the middle.” Then he goes down and tells them, “You’re all equal here, you just need improvement on these things to be up the line so that one standing on the end doesn’t say ‘Well, I was last.'”

They heard you. Their parents did too. You just saved a family from a tough ride home and probably gained a fan for the show.

This takes time—even for judges known for speed like McKinven. But he makes time for kids because the payoff isn’t a ribbon today; it’s a ring full of confident, skilled handlers five years from now.

Judge the Cow That Walked In Today—Not Her Instagram Feed

“If you think she’s third place that day, or second place, and you can support it with reasons, you do it,” McKinven teaches. That line puts steel in your spine when a past grand champion walks in looking off her game.

I’ve watched this play out more times than I care to count. The famous cow enters. Maybe she’s won four or five shows in a row. Everyone knows her. The crowd’s watching for your reaction. Here’s where most judges either cave to pressure or overcompensate by beating her just to prove they can.

McKinven’s approach is different: you don’t beat her to make a point, but you also don’t float her to first on nostalgia. You judge the cow in front of you today. Reputation fills barns; it can’t place classes.

The Politics-Proof Protocol

Here’s how McKinven actually handles reputation pressure—and this comes from watching him navigate some pretty loaded situations:

- Eyes on animals, ears tuned to your own pattern

- When the barn wants to debate later, give them observable reasons

- Walk them through udder attachments, locomotion, rib structure, and balance

- Even people who disagree will understand they were judged, not performed for

“Don’t be intimidated,” McKinven tells judges, “because you might get asked to judge more shows when people recognize politics didn’t sway you—you just placed what you saw that day”.

Judging Across Borders—Fit the Culture, Keep the Standard

What’s fascinating about McKinven’s international experience—32 countries and counting—is how he adapts his approach while maintaining his core standards. This isn’t theory; it’s survival as a traveling judge.

England expects formality. Minimal socializing before the day, tight protocols, careful conduct. You might not see anyone except when you arrive to judge. Much of South America? Completely different. They want to take you to dinner, meet the exhibitors, and have a few drinks. It’s warmer, more social—the show starts the night before.

The Pre-Travel Protocol That Actually Works

McKinven’s learned to ask organizers upfront about local expectations. Here’s his actual checklist (and I’ve started using this myself):

- Contact timeline: When to arrive, buffer time for traffic/delays

- Dress expectations: Formal vs. casual, cultural considerations

- Social obligations: Dinners, meet-and-greets, isolation protocols

- Ring setup: PA systems, translator needs, photo opportunities

- Show flow: Class sizes, timing, steward communication style

Set your pre-show routine regardless: arrive early, walk the ring, test the microphone, identify where you’ll pull animals, and deliver reasons. Adjust your demeanor to match the culture, but keep that evaluation pattern consistent so exhibitors quickly understand what you value.

In regions where environmental conditions affect cattle—such as heat stress, limited forage, and varying feeding systems—McKinven doesn’t penalize the animals for not meeting ideal conditions. He prioritizes function: feet and legs, udder structure, overall balance. Because that’s what works in the real world.

The Stuff That Actually Matters (And Why Most Judges Miss It)

McKinven learned at his father’s kitchen table—”give me a set of reasons” became a daily drill when he was eight years old, looking at magazine photos. Then he married into more mentorship through his father-in-law, who McKinven credits as one of the world’s best judges.

But here’s what separates his approach from the textbook stuff: the technical details matter more than you’d think. McKinven had to learn where to hold the microphone to prevent feedback and where to stand so the reasons came through clearly. That’s professionalism—respect for exhibitors trying to hear and learn from your decisions.

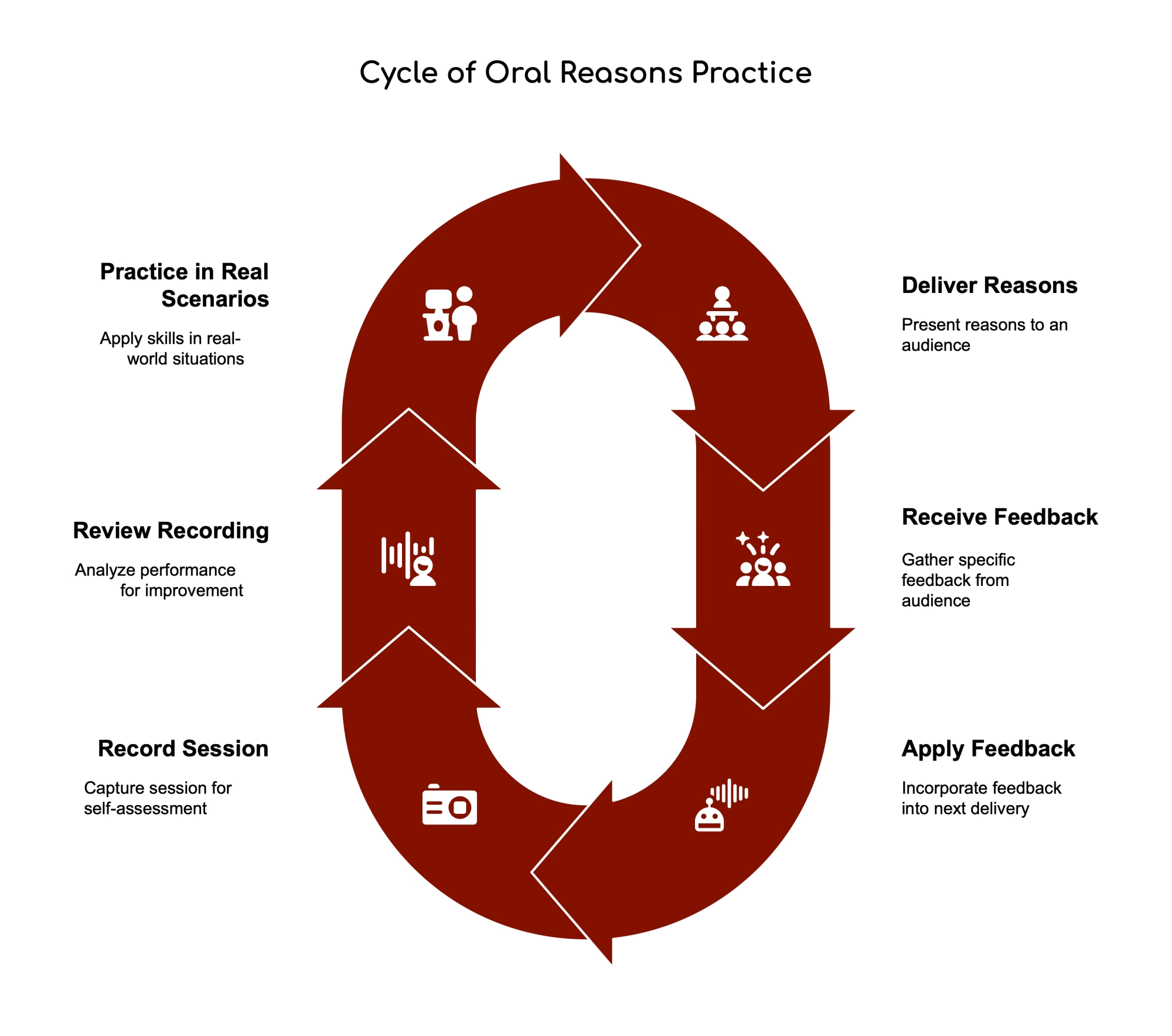

Practice Like Your Reputation Depends On It

Practice reasons in real life, McKinven suggests. You’re milking and comparing two cows? Say it out loud: “This cow’s got deeper rib, stronger pasterns. That cow’s better fore udder attachment.” When adrenaline hits in the ring, practiced language shows up exactly when you need it.

I started doing this after hearing McKinven talk about it, and honestly? It works. Your brain gets comfortable with the language of evaluation when it’s not under pressure.

The McKinven Method: Your Next-Show Playbook

Here is Callum McKinven’s complete system, consolidated into a single checklist you can use to prepare for your next show.

Part 1: The Preparation (Before You Leave Home)

- Lock it Down: The moment you accept an assignment, write it down.

- Do Your Homework: Contact the organizers to inquire about the dress code, cultural expectations, and the show’s schedule.

- Pack Like a Pro: Pack broken-in, comfortable footwear and backup socks. Check the weather and pack appropriate attire.

- Practice Your Language: Rehearse descriptive reasons during daily chores until it becomes automatic. Watch recorded shows to anchor the language to visuals.

- Get Good Sleep: Don’t underestimate the power of being well-rested.

Part 2: The Arrival (The First 30 Minutes)

- Arrive Early: Arrive at least 30 minutes before your scheduled start time.

- Connect with Your Crew: Introduce yourself to the ring stewards and briefly discuss your ring flow and pointing style.

- Walk the Ring: Check the footing, sight lines, and traffic patterns.

- Do a Mic Check: Find the optimal position for giving reasons where you can be heard clearly without feedback.

Part 3: The Ringcraft (During the Show)

- Start Wide: When a class enters, stand back to see the big picture—balance and flow.

- Insist on Movement: Ensure every animal is seen in motion.

- Find Your Rhythm: Don’t rush, but be decisive. Eliminate wasted motion and second-guessing. A confident rhythm builds exhibitor trust.

- Point Clearly: Make your gestures unambiguous. If you make a mistake, correct it quickly and discreetly.

- Follow the Pattern: Stick to your evaluation pattern (Distance → Chest → Profile → etc.) for consistency.

- Use Your “Trait Bank”: Give a maximum of three specific, observable reasons. Use positive language, even for lower placings.

- Judge Today’s Cow: Ignore reputations and crowd noise. Never look at the stands. Judge only the animal in front of you.

Part 4: The Youth Class Approach

- Lower the Temperature: Smile, say good morning, and make eye contact.

- Encourage and Teach: Take extra time to explain. Focus on specific, constructive improvements.

- Use the “Bottom Six” Strategy: For large classes, group the bottom exhibitors and give them shared, positive feedback to avoid singling anyone out.

The Bottom Line

Here’s the thing most people miss about judging: it shapes breeding decisions, and breeding decisions shape the industry we’re handing off. The ring sets standards whether we admit it or not.

When McKinven rewards balance, structural integrity, and functional mammary systems with clear, reasoned decisions, you feel it in bulk tanks six months later. Lower somatic cell counts. Better foot health. Cows that last longer and milk better. That’s not theory—that’s the downstream effect of ring work done right.

I’ve been watching this industry for long enough to see patterns. Farms that consistently show and breed for the traits McKinven prioritizes—balance, function, udder quality—tend to have better profit margins. Their replacement rates are lower. Their veterinary costs are more manageable. Their milk quality premiums are higher.

The Ecuador Effect

What struck me about that Ecuador clinic wasn’t just McKinven’s technical knowledge—it was his passion for getting this right. Because he understands something a lot of judges miss: every placement decision ripples outward. Every young exhibitor who walks away feeling confident might stay in the industry. Every reason given clearly and positively teaches someone something new.

McKinven’s approach wasn’t about tricks or shortcuts. It was about discipline. Start wide. Keep a consistent pattern. Move the ring with purpose. Speak about what you see. Build up young exhibitors. Judge today’s cow—period.

And on your best day, with a packed house and a sticky class at the end… that standard is what carries you through.

Key Takeaways:

- Judge today’s cow, not her reputation: keep eyes on the ring, not the crowd; place off observable traits—udder attachments, locomotion, rib and balance.

- Start wide and insist on movement: distance scan for balance, then work a repeatable pattern (chest → profile → legs/feet → rib/angularity → mammary) for every class size.

- Stop memorizing; start seeing: give three concise, positive, trait-based reasons while looking at the animals—no vague “nicer/better” language.

- Youth classes need calm leadership: smile, explain placements, and use the “bottom six” grouping in large classes to coach without embarrassment.

- Professionalism builds trust: lock dates immediately, arrive 30 minutes or more early, dress professionally, wear well-fitted footwear, and coordinate ring flow and mic position with stewards.

A special thank you to the organizations that made this feature possible. The Bullvine’s coverage of the Ecuador National Show and judging clinic was proudly supported by Semex, the Association Holstein Del Ecuador, and the Centro Agropecuario Cantonal Ambato. We appreciate their commitment to advancing dairy genetics and judicial education.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

In the expansive heartland of America, where fields unfurl beneath the boundless sky and the air carries the sweet aroma of fresh hay, a figure like Dr. David Selner stands as a steadfast pulse of the dairy industry. From humble beginnings on a Wisconsin dairy farm, he blossomed into a symbol of creativity and commitment, taking on roles that ranged from genetic consultant to beloved mentor. Dr. Selner, a beacon of dedication whose contributions reshaped the dairy landscape, has left a lasting legacy in an industry that sustains countless lives. Dr. Selner’s legacy resonates profoundly and is woven into the fabric of countless lives he impacted worldwide. In the wake of his recent passing on October 25, 2024, after a courageous fight against pancreatic cancer, we are left to contemplate the profound impact of his life’s work.

In the expansive heartland of America, where fields unfurl beneath the boundless sky and the air carries the sweet aroma of fresh hay, a figure like Dr. David Selner stands as a steadfast pulse of the dairy industry. From humble beginnings on a Wisconsin dairy farm, he blossomed into a symbol of creativity and commitment, taking on roles that ranged from genetic consultant to beloved mentor. Dr. Selner, a beacon of dedication whose contributions reshaped the dairy landscape, has left a lasting legacy in an industry that sustains countless lives. Dr. Selner’s legacy resonates profoundly and is woven into the fabric of countless lives he impacted worldwide. In the wake of his recent passing on October 25, 2024, after a courageous fight against pancreatic cancer, we are left to contemplate the profound impact of his life’s work.