Mercosur was sold as “modest.” The math says 550 EU family herds’ milk and a headwind that can shave cents off every litre you ship. Ready to see where you stand?

Executive Summary: EU dairy farmers are walking into the Mercosur era with costs already running hot, milk output basically flat at about 149.4 million tonnes, and some of the toughest environmental and welfare rules anywhere. The “modest” EU–Mercosur deal quietly opens the door to 30,000 tonnes of cheese, 10,000 tonnes of milk powder, and 5,000 tonnes of infant formula on zero‑tariff quotas once it’s fully phased in—roughly 345,000 tonnes of milk when you convert it back to tanker‑loads. That’s the annual production of more than 500 average EU family herds trying to find a home in a market where cow numbers and drinking‑milk use are already slipping. This article walks through that “Mercosur math,” shows what those quota volumes could mean for your milk cheque over a season, and lays out the practical questions every EU dairy should be asking about compliance costs, product mix, and risk‑sharing with processors.

You know that feeling. The milk cheque shows up, it’s lighter than you hoped, the co‑op newsletter says it’s been “a solid year,” and then the radio starts talking about Brussels pushing the EU–Mercosur trade deal across the finish line.

That’s usually when the questions you’ve been parking for months finally bubble up: “So what does this actually mean for my milk price? For our cows? For whether this place is still viable ten years from now?” Those are fair questions. And they deserve more than slogans, whether they’re coming from farm groups or politicians.

So let’s walk through this together. We’ll start with the cost pressure you’re already feeling, then dig into what’s really in the Mercosur dairy package, translate it into tanker loads and euros, and finish with some practical things you can do at the kitchen table over the next 90 days.

Looking at the Cost Gap We’re Up Against

Looking at this trend over the last five years, here’s what’s interesting: every major dairy region has seen costs go up, but not at the same speed or from the same starting point.

AHDB in the UK pulled together a clear summary of Rabobank’s latest global milk production cost work early in 2025. They looked at eight big exporting regions—Argentina, Australia, China, Ireland, New Zealand, the Netherlands, California, and the US Upper Midwest—from 2019 through 2024. Across that group, average total production costs rose about 14%, which works out to roughly 6 US cents more per litre over that period, and more than 70% of that increase occurred between 2021 and 2024, as feed, energy, and labour spiked. Rabobank’s team also highlighted that feed expenses were the main culprit, with average feed bills across those regions up around 19% since 2019.

The same work shows Oceania at the sharp end of low‑cost production. New Zealand and Australia have been neck‑and‑neck for the lowest cost among the eight regions, with a five‑year average total cost of about US$0.37 per litre versus roughly US$0.48 for the others. That’s roughly a 17% advantage for Oceania once you standardise for milk composition and express everything in US dollars. By contrast, production costs in local currencies in the US, the Netherlands, and China rose about 10–20% over that period, around 25% in Australia and New Zealand, and roughly 30–40% in Ireland and Argentina.

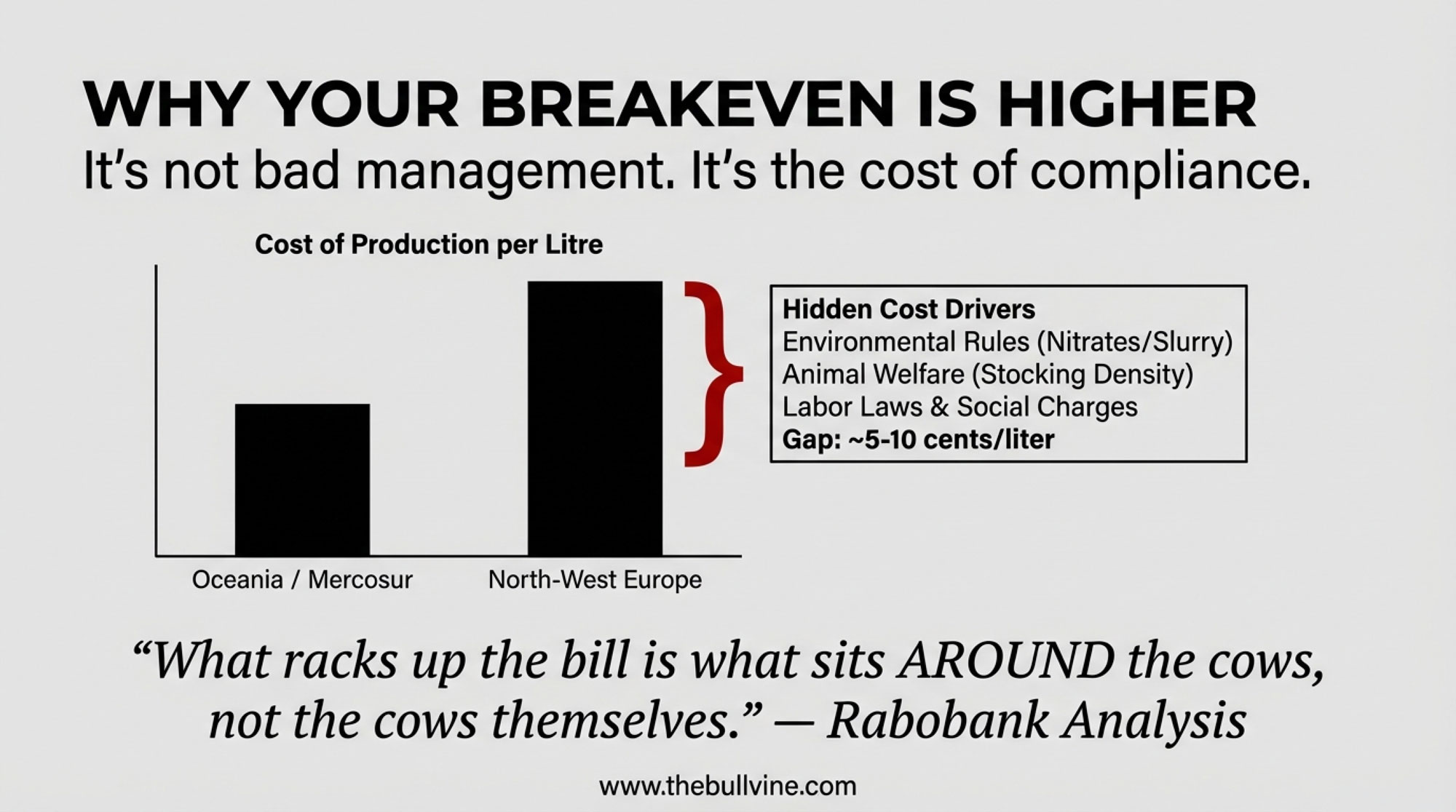

What I’ve found, looking across north‑west Europe, is that this lines up pretty well with what many of you are seeing in your own books. Once you add feed, labour, power, interest, and then the cost of complying with environmental and animal‑welfare rules, you’re often looking at a cost base that’s several euros per 100 kg higher than a low‑cost pasture system in New Zealand or some of the better Mercosur herds. Rabobank’s comparisons suggest that on a typical European cost level, that 17% gap can easily translate into a few euros per 100 kg of milk once everything is counted in.

And it’s not that EU cows are managed badly. In most freestall herds in France, Germany, the Netherlands, or Ireland, butterfat performance, fresh cow management during the transition period, and general cow comfort would look very familiar to good herds in Wisconsin or Ontario. What really racks up the bill is what sits around the cows rather than the cows themselves.

So where do those extra euros actually hide:

- Animal‑welfare and environmental rules that govern cubicle dimensions, stocking densities, bedding, sometimes minimum days on pasture, and increasingly strict slurry and housing rules tied to EU nitrates and climate policy

- Traceability and food‑safety systems that mean more tagging, sampling, milk recording, and third‑party audits than you’d see in many lower‑regulation exporting regions

- Labour laws and social charges that make every hired hour more expensive than in much of South America or Oceania

What’s interesting is that when families actually sit down with their accountant and a highlighter, and pull out projects and costs that exist mainly because of regulation—extra lagoon capacity, environmental testing, certification and audit fees, software for traceability systems—it’s common to end up with a compliance bill in the low single‑digits of euro cents per kilo of milk. A recent systematic review of milk quality and economic indicators in dairy farming backs up the idea that quality schemes and regulatory measures are significant cost drivers, even if the exact cents‑per‑litre number varies from farm to farm. It’s not some official EU‑wide metric, but it’s big enough to matter, especially when global prices turn down.

That’s the cost base Mercosur milk and cheese is going to be bumping into.

What’s Actually in the Mercosur Dairy Package?

So, what’s actually in this deal? Because you’ve probably heard everything from “it’s a minor opening” to “it’ll wipe out EU dairy.”

EU trade documents on the EU–Mercosur association agreement, along with analysis from AHDB, all draw a very similar picture. On the dairy side, the agreement adds new duty‑free tariff‑rate quotas (TRQs) for three main products:

- Up to 30,000 tonnes of cheese per year, where current most‑favoured‑nation tariffs sit around 28%

- Up to 10,000 tonnes of milk powder per year, also dropping from roughly 28% to zero in‑quota

- Up to 5,000 tonnes of infant formula per year, down from about 18% duty to zero on those quota volumes

These aren’t switched on at full volume on day one. European Dairy Association commentary notes that cheese quotas are expected to start around 3,000 tonnes in the first year and then step up to 30,000 tonnes by year ten, while milk powder TRQs move from 1,000 to 10,000 tonnes over the same period. Infant formula quotas are phased in to a final volume of 5,000 tonnes.

On the flip side, EU processors gain better access to Mercosur markets—especially Brazil—for European cheeses, powders, and infant nutrition products, plus stronger protection for EU geographical indications, such as key cheese names. That’s why you see support from groups like the European Dairy Association; they’re looking at supermarket shelves in São Paulo as much as at your yard in Brittany.

But if you’re milking cows in Bavaria or western France, the key question isn’t “is this good for EU industrial exports overall?” It’s “what do those tonnes actually mean on the milk side and on my milk cheque?”

Turning Policy Tonnes Into Tanker Loads

This is where the math gets real.

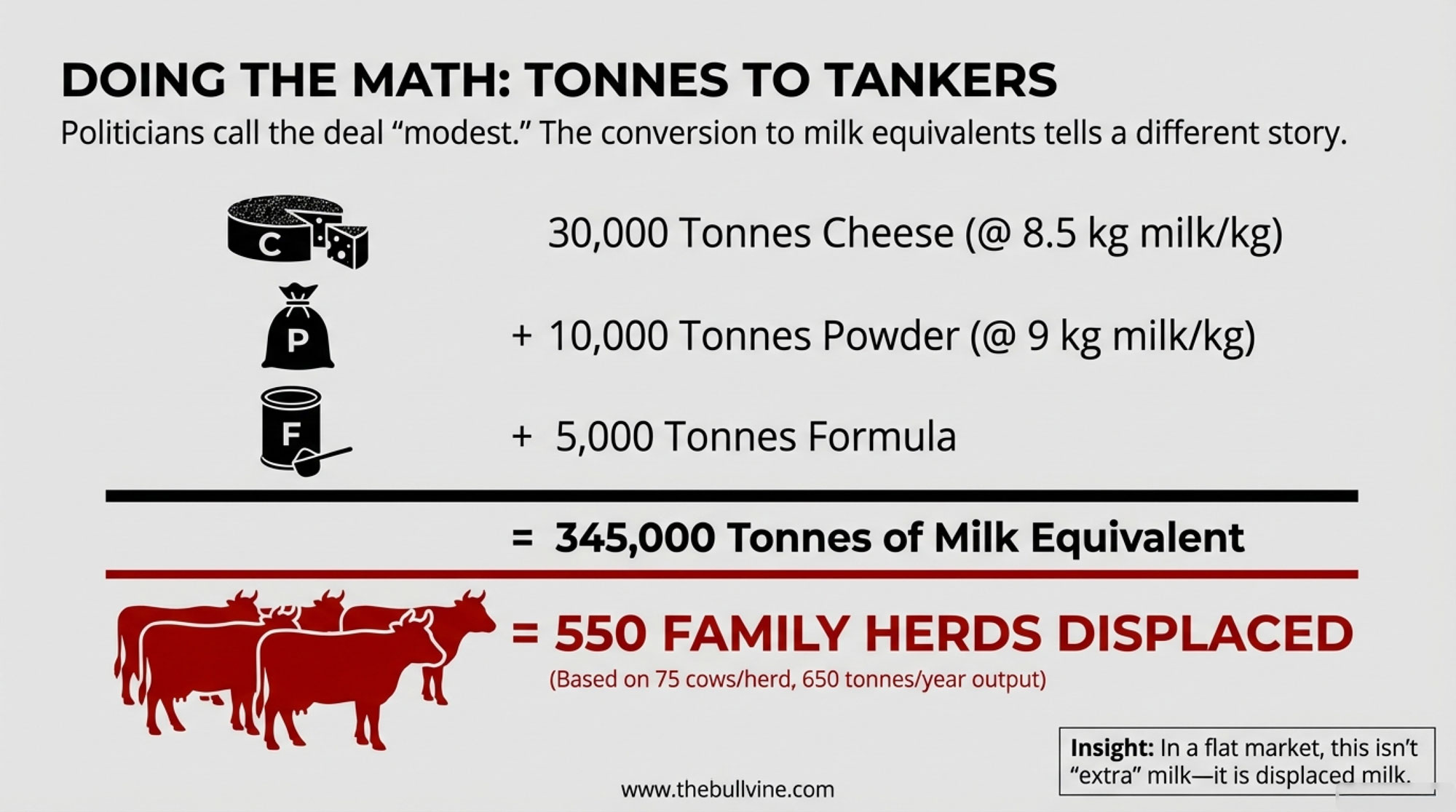

On paper, 30,000 tonnes of cheese doesn’t sound like much when the EU produces close to 150 million tonnes of milk. To get a feel for it, you have to convert that cheese and powder back into the milk that made it.

Cheese makers often use a rule of thumb of roughly 8.5 kg of whole milk to produce 1 kg of semi‑hard cheese, depending on fat and protein levels. For milk powder, typical technical references put whole milk powder at around 7.8 kg of milk per kg of powder and skim milk powder at just over 10 kg; using 9 as a blended average for a basket of powders is a fair shorthand.

If we run those numbers:

- Cheese: 30,000 tonnes × 8.5 kg milk/kg cheese ≈ 255,000 tonnes of milk equivalent

- Powder: 10,000 tonnes × 9 kg milk/kg powder ≈ 90,000 tonnes of milk equivalent

Together, that’s roughly 345,000 tonnes of milk equivalent per year, once those quotas are fully ramped up.

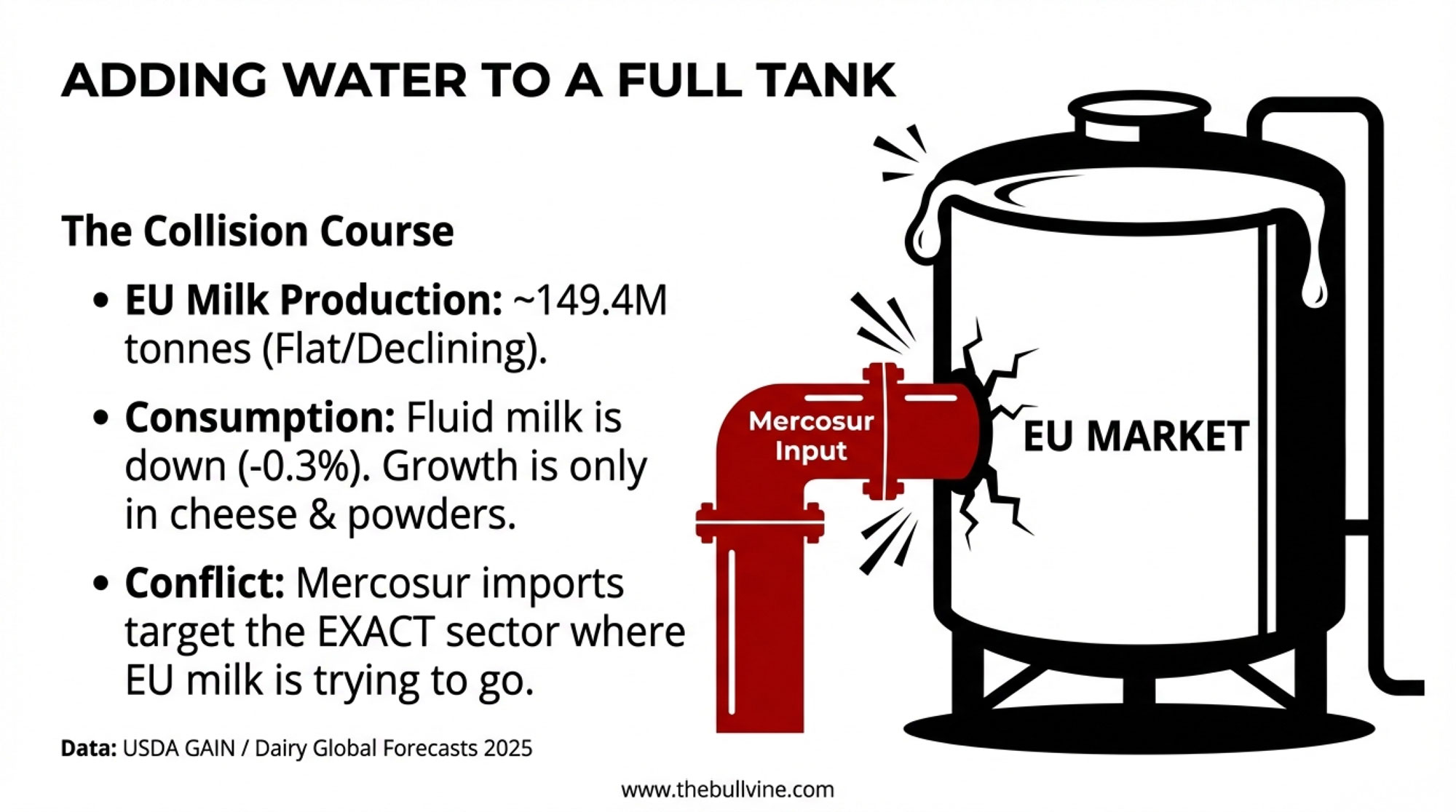

Now let’s lay that alongside EU milk production.

A USDA GAIN report on the EU, summarised by Dairy Global, forecasts total EU milk deliveries at about 149.4 million tonnes in 2025, roughly 0.2% below a revised estimate for 2024. That same analysis expects domestic consumption of fluid milk to keep easing and notes that cheese production is likely to edge higher, with more milk being channelled to cheese and powders.

So, into a basically flat pool of around 149–150 million tonnes, you add the equivalent of 345,000 tonnes of milk.

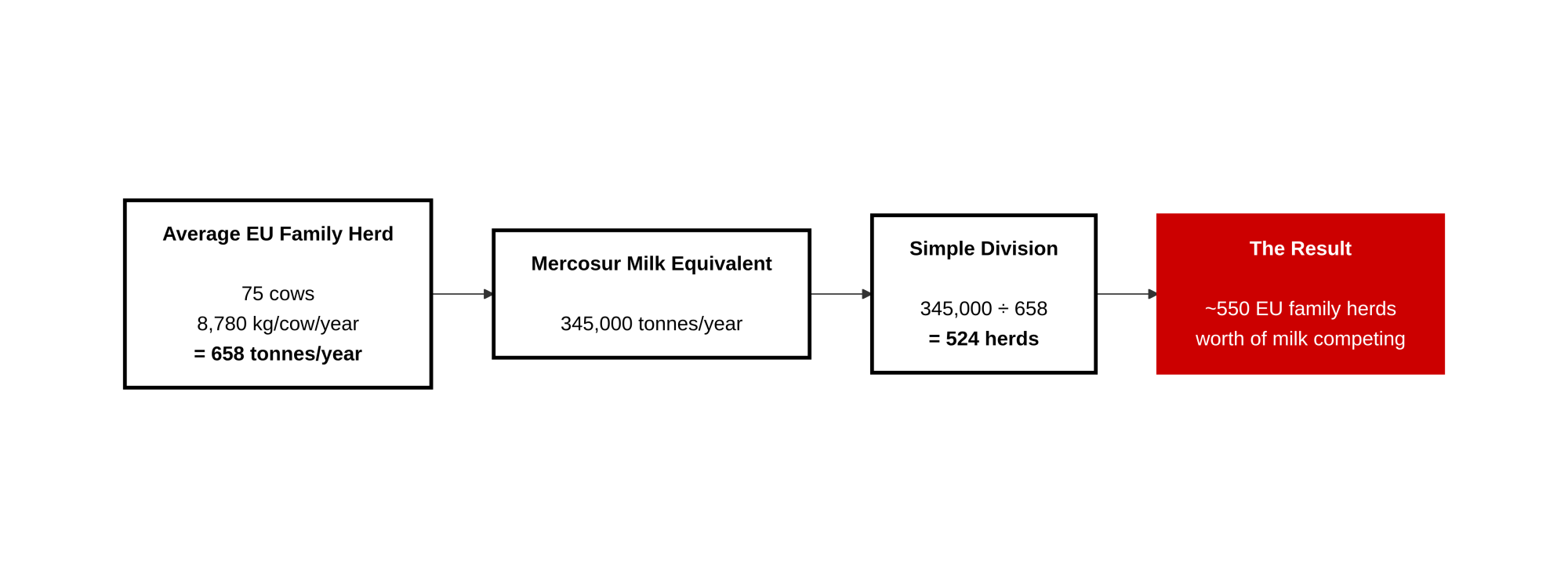

To make that concrete, German data from BZL show that by the end of 2023, Germany had 50,581 dairy cattle holdings—about 2,400 fewer than in 2022—and a national herd of roughly 3.7 million cows, down 2.5% in a year. Average yield was around 8,780 kg per cow, up from 8,504 kg in 2022. On those numbers, a 75‑cow family herd ships roughly 658,500 kg—call it 650 tonnes—of milk per year.

Divide 345,000 tonnes of milk equivalent by 650 tonnes per 75‑cow herd, and you’re looking at the annual output of about 530–550 herds of that size.

No, that doesn’t mean 550 farms will shut their doors the day this deal kicks in. Markets don’t work in straight lines. But you can see why something labelled as a “modest” quota package starts to feel a lot less modest when you translate it into tanker loads and real farms.

And if you turn that into price pressure, here’s a handy way to think about it. Say that extra competition from Mercosur trims the milk price by an average of 1–2 cents per litre over a cycle. On 650,000 litres of milk, that’s €6,500–€13,000 a year. On 2 million litres, you’re talking €20,000–€40,000. It’s not a forecast; it’s just basic arithmetic. But it puts a number on what “a bit more headwind” could mean in everyday cash‑flow terms.

| Annual Milk Volume | Impact at 1 cent/L | Impact at 2 cents/L |

|---|---|---|

| 500,000 L | €5,000 | €10,000 |

| 650,000 L | €6,500 | €13,000 |

| 1,000,000 L | €10,000 | €20,000 |

| 2,000,000 L | €20,000 | €40,000 |

Where the EU Dairy Sector Is Starting From

Before we hang everything on Mercosur, it’s worth being honest about where EU dairy already stands.

The same three threads keep showing up in USDA GAIN summaries, forecast, and national statistics.

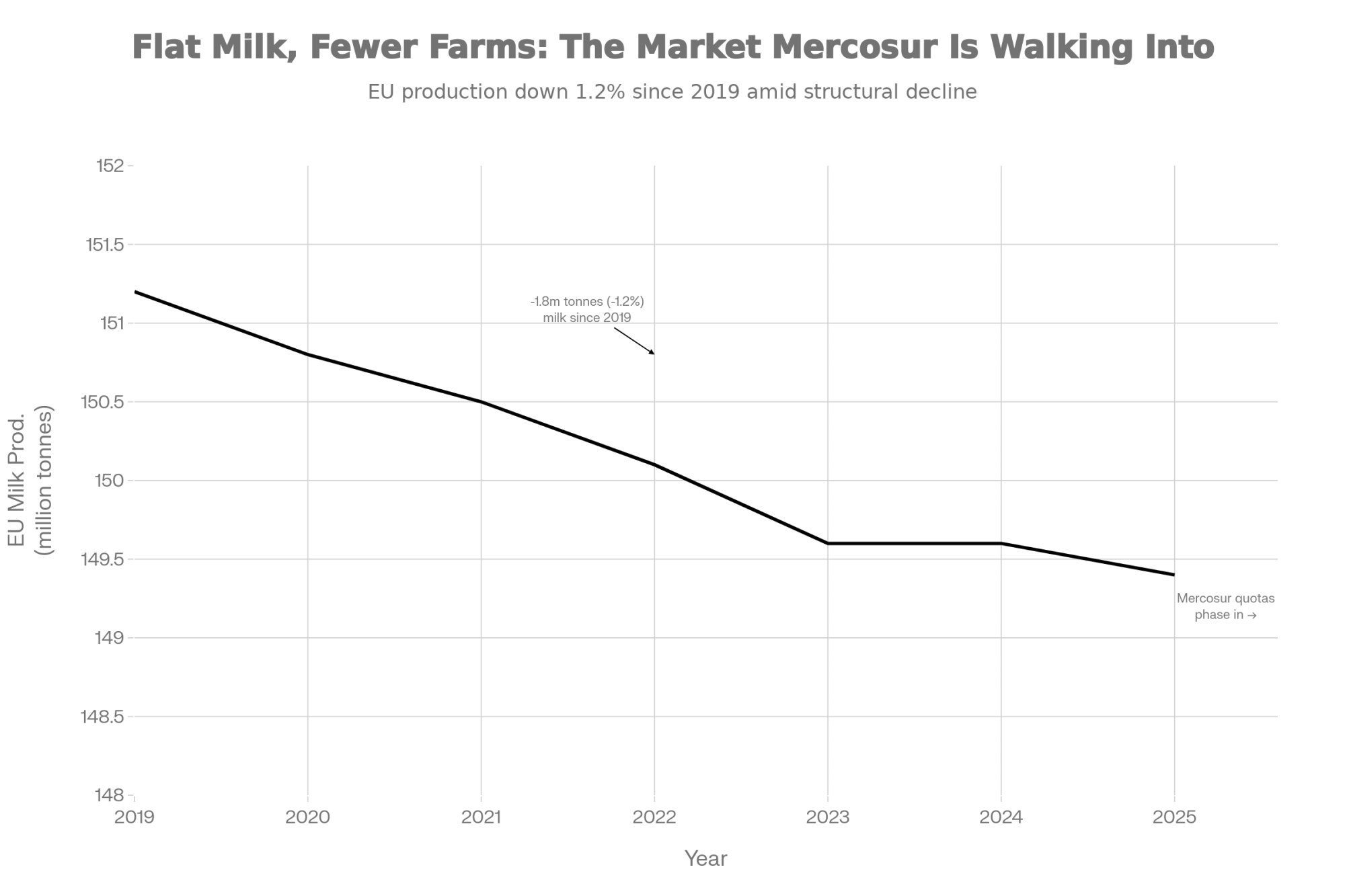

First, milk production is flat to slightly down. For 2025, EU milk deliveries are forecast at about 149.4 million tonnes, 0.2% below 2024, as tight margins, environmental restrictions, and disease pressures push some smaller farmers out and cow numbers keep easing.

| Year | EU Milk Production (M tonnes) | German Dairy Farms (thousands) |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 151.2 | 64.5 |

| 2020 | 150.8 | 62.5 |

| 2021 | 150.5 | 60.4 |

| 2022 | 150.1 | 53.0 |

| 2023 | 149.6 | 50.6 |

| 2024 | 149.6 (est.) | — |

| 2025 | 149.4 (forecast) | — |

Second, cow numbers and farm numbers are steadily shrinking. We already talked about Germany losing about 2,400 dairy farmers in 2023, with cow numbers slipping to 3.7 million and average yields rising to 8,780 kg. Similar structural change is underway in France and the Netherlands, even if the exact figures differ.

Third, the product mix is shifting. The same GAIN‑based forecast expects domestic fluid‑milk consumption to continue declining, down by about 0.3% in 2025, while cheese production holds or grows slightly, and more milk heads into cheese and powders.

If you glance across the Atlantic, you see a related pattern. Hoard’s Dairyman recently highlighted that average US butterfat in the national bulk tank has climbed steadily, with annual averages moving from roughly 4.01% in 2021 to about 4.15% in 2023, and monthly data in 2024 showing every month at or above 4.0% fat. That mirrors what many of you are seeing on your own test sheets: cows that used to sit at 3.6–3.7% butterfat now comfortably over 4.0. In the Upper Midwest, for example, butterfat in the federal order serving Wisconsin averaged over 4% for the first time in 2021, driven by the cheese focus in that region.

So the EU isn’t unique. High‑standard dairy regions worldwide are trying to get more value out of every litre—more fat, more protein, more cheese yield—without relying on endless volume growth. The twist is that EU farms are doing it under some of the strictest welfare and environmental rules anywhere, which means their cost of production is higher before they even start.

And if you’re reading this in Wisconsin, Ontario, or Canterbury, you’ll recognise some of these pressures: higher input costs, tighter environmental expectations, more scrutiny from buyers, and a slow drift away from fluid milk into cheese and ingredients. The details differ, but the direction of travel feels familiar.

So What Does This Do to Price?

This is the question everyone wants answered in one number: “How much does Mercosur take off my litre?”

Here’s the honest take: nobody reputable is putting a clean, Mercosur‑only discount into a forecast yet. But there are enough signals to sketch the shape of the impact.

Rabobank’s work on structural costs makes a straightforward point: regions like north‑west Europe, with higher labour, land, and regulatory costs, will face ongoing margin pressure if they’re playing in global commodity markets. The path forward, in their view, is more scale, more differentiation, or both.

Analysis of Rabobank’s 2024 outlook for EU farmers notes that margins are expected to improve compared to the worst of 2022, with an average base price in the high 40s €/100 kg, but it also warns that costs remain elevated and that weaker Chinese demand and low output in Argentina are key uncertainties. AHDB’s own work on 2024–2025 costs underlines that while fertiliser and some purchased feeds have come off their peaks, total production expenses are still well above 2019 levels.

Then you drop Mercosur into that picture. You’ve got a mature, high‑cost market, where milk volume is flattening, and you add a stream of lower‑cost cheese and powder competing at the commodity end. Over time, that acts like a headwind on prices—peaks don’t climb quite as high, and recoveries after a downturn can be slower and shallower.

Farm organisations have been very clear on this. Groups like the European Milk Board and Copa‑Cogeca argue that EU farmers are being asked to meet some of the strictest environmental and animal‑welfare standards in the world while competing against imports that don’t face those same on‑farm obligations. They see the risk that, unless the value chain pays properly for higher standards, more low‑cost imports will tighten already narrow margins and accelerate structural change.

On the other side, the European Dairy Association and export‑oriented processors see opportunities. They’ve publicly welcomed progress on the EU–Mercosur deal, pointing to better access for EU cheeses and ingredients, and stronger protection for European cheese names, as ways to grow value in Mercosur markets. From their perspective, this is about getting more branded EU product onto high‑value shelves abroad.

The short version? For a commodity‑leaning family farm, Mercosur is another weight on a scale that was already tipping toward tighter margins. For a processor with good brands and strong GI‑protected products, it’s a mix of added risk at home and new opportunity abroad. And for the co‑ops and private buyers in the middle, it raises the stakes on how they share risk and reward with suppliers.

In some regions, you’re starting to see buyers offer longer‑term cost‑plus or fixed‑margin contracts on a slice of milk—tying pay‑out more closely to real costs for part of your volume—which is one way to spread the risk between farm and plant. It’s still early days for those models, though. Most of you are still living off the commodity roller coaster.

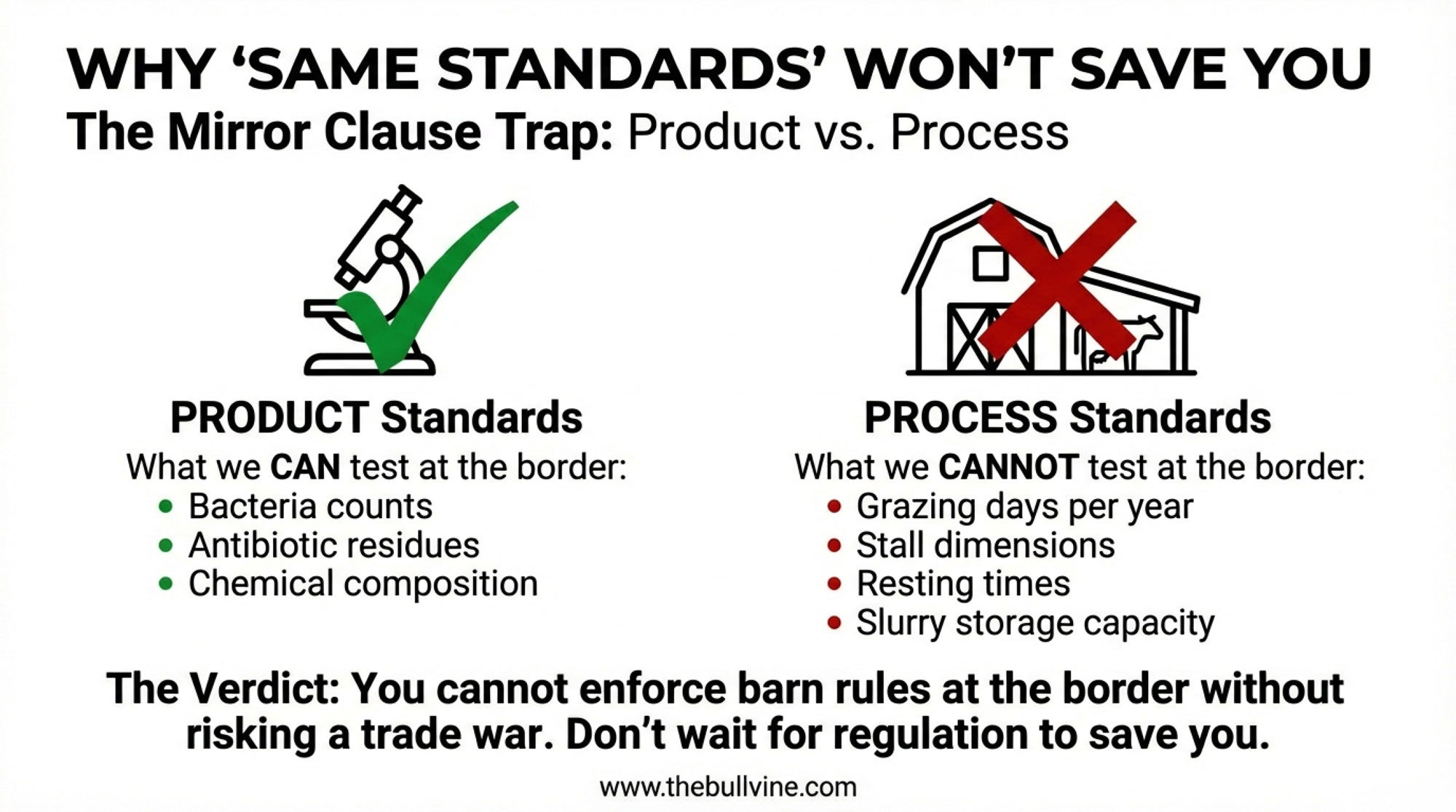

Mirror Clauses: Why “Same Standards for Imports” Is Harder Than It Sounds

When farmers hear all this, it’s totally understandable that the first instinct is: “Fine—if they want to ship dairy here, make them meet our standards.”

On principle, it feels fair. You’ve invested in better housing, in slurry storage that actually holds enough for the whole winter, in emissions and nutrient management plans, in full traceability. Why should you compete with milk that hasn’t carried the same load?

The catch is that most of what drives your cost is about how things are done, not the physical product you test at the dairy plant. That’s where life gets tricky for mirror‑clause ideas.

You can lab‑test cheese and milk powder for residues, pathogens, and composition. You can’t test a block of cheese for stall dimensions, resting time, or whether the cows had 120 grazing days that year. Those are process standards. They’re invisible at the border.

We’ve already seen how tough that gets with the EU’s deforestation regulation. When Brussels moved to regulate imports linked to illegal deforestation, there was a lot of optimism that satellite imagery and digital tools would make things straightforward. In practice, enforcement has run into mismatches between forest maps and national land registries, patchy local records in exporting regions, and the sheer volume of supply chains that have to be traced. Dairy would have similar traceability headaches, just without the helpful “forest/no forest” satellite contrast.

Trade lawyers also point out that under WTO rules, it’s generally easier to defend restrictions based on what a product is—its composition, safety, or residues—than on production methods that don’t change the product itself. Push too far on telling exporting countries they have to run their barns and manure systems just like Europe does, and you risk a trade dispute that’s hard to win.

There’s also a simple economic angle. If Mercosur exporters really had to meet fully equivalent EU‑level requirements for housing, slurry storage, and emissions—and if those rules were enforced correctly—their cost advantage would shrink. At that point, their appetite for pushing big volumes into an already competitive EU dairy market might cool.

So mirror clauses are likely to make inroads on some clear things—keeping banned substances out of the food chain, tightening traceability on deforestation-linked feed—but they’re not a magic wand for equalising on‑farm standards and costs in the near term.

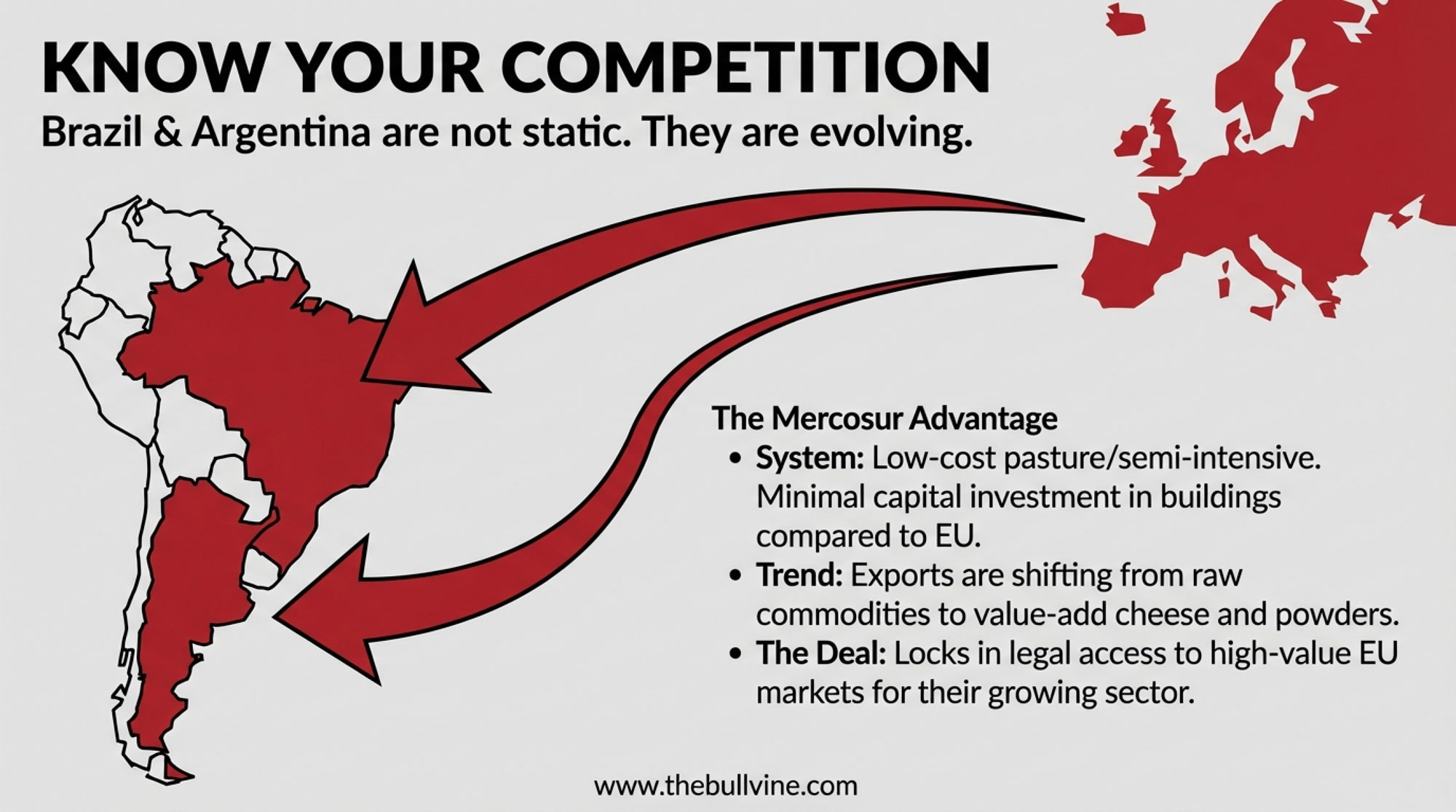

What’s Going On in Mercosur Dairy?

To keep this fair, we shouldn’t pretend Mercosur is static either.

Brazil and Argentina are the main dairy players in that bloc. Global trade reports and USDA’s “Dairy: World Markets and Trade” show that over the last decade, both countries have increased dairy exports, particularly in whole‑milk powder, cheese, and UHT milk, into neighbouring Latin American markets, North Africa, and parts of the Middle East. Brazil, in particular, has swung between being a net importer and a net exporter depending on domestic demand, currency, and policy.

If you look at typical export‑oriented herds in those regions, you see a lot more pasture and semi‑intensive systems than full concrete‑and‑steel freestalls. Housing tends to be lighter, with cows spending more time on grass and less in enclosed barns. Land and labour costs, in local terms, are generally lower than in north‑west Europe, even allowing for inflation and volatility. Environmental and animal‑welfare rules exist and are evolving, but they don’t yet put the same pressure on stocking rates, slurry storage, or greenhouse gas accounting that EU farmers are now dealing with.

Rabobank’s cost analysis notes that while production costs in Argentina and Ireland have jumped 30–40% in local currency since 2019, farms in low‑cost pasture systems still tend to sit below EU per‑litre costs because they started from a lower base and have fewer regulatory-driven capital investments to service.

From a Mercosur perspective, the EU deal is about locking in stable, rules‑based access to a high‑value market. From Brussels’ perspective, dairy is one moving part in a larger trade‑off that also covers sectors like cars and machinery, where the political stakes are high.

And from your parlour? It’s another external force you can’t control but have to respond to, just like feed markets or weather.

How Some Farms Are Adjusting Their Playbook

So let’s bring this back to the farm gate. Given higher structural costs, flat or slowly easing milk volumes, and this new trade headwind, what can a dairy actually do?

What I’ve noticed, visiting herds and talking with producers in Germany, the Netherlands, France, and Ireland—and comparing notes with folks in Wisconsin or Ontario facing their own pressures—is that farms which seem to be staying a step ahead have a few habits in common.

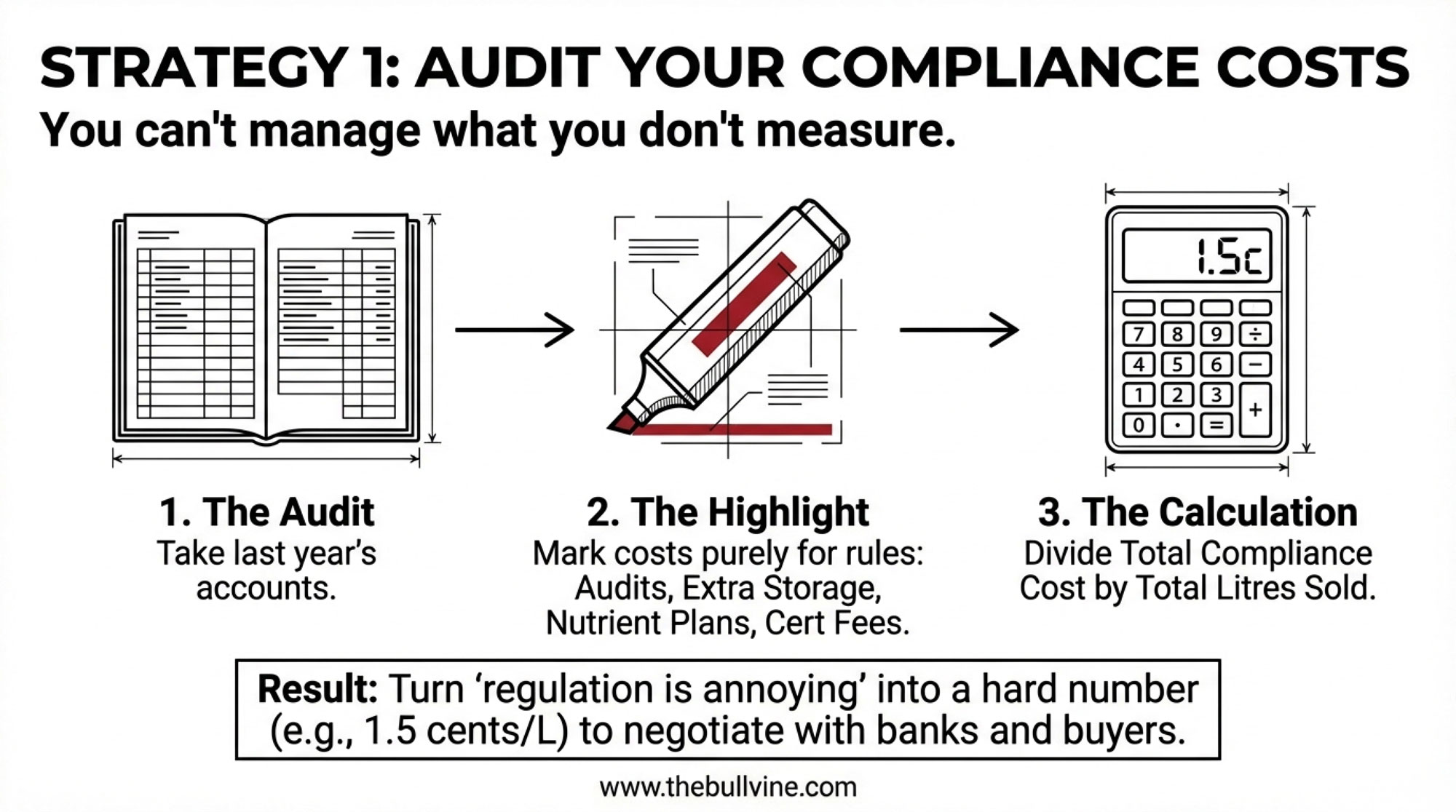

1. Treating Compliance as a Real Cost, Not Just a Headache

A lot of us complain about regulation, but relatively few actually put a number on it. On the herds that do, the conversation changes fast.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

- They list capital projects where regulations were the main driver—extra slurry storage to meet new rules, lagoon covers for emissions, manure separators, stall renovations for welfare standards, upgraded ventilation that goes beyond pure production needs

- They pull out ongoing expenses that are mostly about compliance—environmental sampling, emissions monitoring, nutrient‑management plans, audit and certification fees, software licences for traceability and quality programmes

- They estimate the labour hours that go into paperwork and inspections that simply wouldn’t exist in a lower‑regulation environment

When you add those up and divide by litres delivered, you don’t get a perfect number. But you do get a rough compliance cost per 100 kg. On some farms, that works out to just above one cent per kilo; on others, especially right after big environmental investments, it creeps closer to two or three. A 2024 systematic review on milk quality and economic sustainability makes the same point: regulatory and quality‑scheme demands are a real component of total cost, and they vary widely by system and region.

A simple way to start is this: print last year’s accounts, grab a highlighter, and mark anything that’s there primarily because of regulations or certification schemes. On one European case example, that list looked like roughly €12,000 for extra slurry storage, €3,000 for environmental testing and nutrient planning, and €1,500 in audit and certification fees—about €16,500 spread over roughly 800,000 litres. That’s the kind of breakdown that turns “regulation is expensive” into something you can actually talk through with your bank, your advisor, and your buyer.

| Compliance Cost Component | Typical Annual Cost (EUR) | Cost Type |

|---|---|---|

| Extra slurry storage (beyond production need) | €2,000 | Amortized |

| Environmental testing & nutrient plans | €3,000 | Recurring |

| Audit & certification fees | €1,500 | Recurring |

| Emissions monitoring equipment | €1,200 | Amortized |

| Traceability software & milk recording | €800 | Recurring |

| Welfare-driven barn upgrades | €3,500 | Amortized |

| TOTAL (Annual Equivalent) | €12,000 | Mixed |

Once you’ve got your own ballpark compliance cost written down, a few deeper questions come almost automatically:

- Are we carrying too much fixed compliance infrastructure for the litres we’re producing?

- Does our current herd size spread those fixed costs sensibly?

- Are we picking up any premium for the standards we’re already meeting, or are we just ticking boxes?

You don’t have to like the answers. But you can’t manage what you won’t measure.

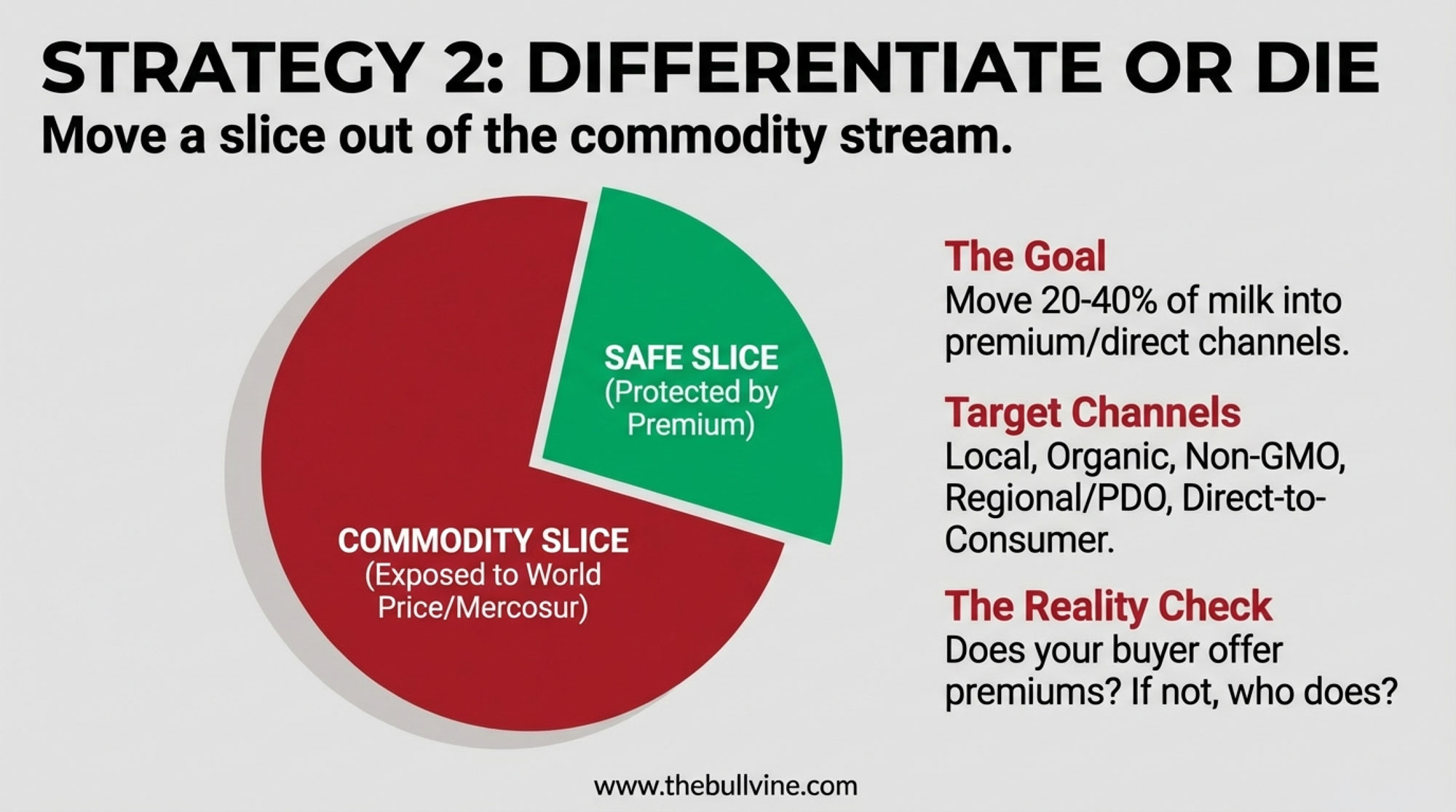

2. Moving a Slice of Milk Out of the Commodity Stream

The second pattern you see, especially near towns and cities, is farms that accept they can’t compete on cost for every litre, so they move a slice of their milk into a different game.

We’re not talking massive on‑farm bottling plants. A typical success story looks more like this:

- An 80–120‑cow freestall or loose‑housing herd on the edge of a Dutch town, a German city, or a French provincial centre

- Modest capital spend—a small pasteuriser, one or two simple cheese vats, decent refrigeration, and either a tidy farm shop or a regular place at local markets

- A family member who doesn’t mind dealing with customers and local social media

Case studies out of regions like Minas Gerais in Brazil and various European direct‑sale operations show that when everything is set up sensibly, the milk that goes through that direct channel can net 20–40% more per litre than the base co‑op price, after you’ve covered packaging, extra labour, and energy. The majority of milk still goes on the truck. But that 20–40% slice can be the difference between a red year and a black one.

Of course, that’s the best‑case scenario. You probably know someone whose on‑farm processing turned into an expensive, exhausting second job. The key conditions that keep coming up, both in the research and in real herd stories, are:

- You’re within a reasonable distance of enough customers who value local dairy

- You keep the product range focused and manageable

- You run the numbers hard, including your own time and the extra compliance burden

So before you rush out to buy a pasteuriser, it’s worth asking:

- Are we close enough to a town or city with people who’ll pay more for local milk and cheese?

- Do we have someone in the family who genuinely likes selling and storytelling, not just milking and scraping?

- What existing platforms—farmers’ markets, local food shops, online “farm‑to‑door” schemes—could we plug into first, before we build everything ourselves?

If you can line up “yes” answers for those, then looking at a small, seasonal product line—like ice cream or fresh cheese—might be a sensible toe‑in‑the‑water move.

3. Turning Constraints Into a Product Story

In mountain and hill regions, the options look different again. You’re dealing with slopes, short growing seasons, and fragmented fields. Big dry lot systems or 700‑cow freestalls just aren’t realistic on that ground.

What’s encouraging is that some of these farms are still hanging in—and some are thriving—because their milk is tied into PDO or GI cheeses and dairy products with strong regional identities. Studies of mountain dairy systems in the Alps and other upland regions show that farms linked into well‑managed GI value chains often receive higher average prices per kilo of solids than standard commodity milk, though they also face higher production costs and depend more on environmental payments.

In other words, they’ve turned what might look like “inefficiencies”—steep land, traditional breeds, strict building rules—into part of the brand and value story.

If you’re already in one of those regions, or your co‑op is talking about building a new origin or welfare scheme, you might want to ask three blunt questions:

- What’s the average farm‑gate price difference compared with standard milk for farms actually in the scheme?

- How many local farms have successfully transitioned into it, and what did they have to change in terms of housing, feeding, or certification?

- How steady has that premium been through the last couple of price cycles?

Research and farm‑level evidence suggest that in some regions the premium holds up well; in others, it narrows during low‑price periods. Knowing which kind of region you’re in matters before you commit to major changes.

Five Questions for a Winter Night at the Kitchen Table

By this point, it’s easy to feel like the world is throwing too many variables at you at once: global costs, trade deals, standards, climate, and consumer shifts. You can’t fix any of those alone.

What you can do is see your own situation clearly and make a few deliberate moves.

Here are five questions worth scribbling down and working through with whoever shares in the decisions on your farm.

1. What’s our best estimate of compliance cost per 100 kilos?

Grab last year’s accounts and a highlighter. Mark the items that wouldn’t be there—or would be much smaller—if you didn’t have to meet today’s environmental, welfare, and traceability rules: slurry and storage projects, environmental testing, nutrient plans, emissions monitoring, audit fees, and software for quality schemes. Add them up and divide by your litres. It won’t be perfect, but it will turn “regulation is expensive” into a number you can bring to your bank, your advisor, and your processor.

2. Does our current scale fit our region and our system?

Very small herds sometimes survive with low debt and off‑farm income. Very large units spread fixed costs—buildings, slurry, compliance, labour—over a lot of litres. The 60–200‑cow, fully regulated freestall herd is often caught hardest—too big to be a hobby, too small to spread heavy fixed overhead comfortably. Given your land base, labour, building layout, and local rules, are you trying to carry more cows than you can handle efficiently, or is your physical and regulatory infrastructure too big for your current litres?

3. Where does each litre of our milk actually go—and under what contract terms?

Map it out. How much milk goes into pure commodity cheese and powder pools? How much, if any, goes into premium streams—pasture‑based, non‑GMO, organic, higher‑welfare, local‑origin? A good question for your buyer is: “What premium programmes—pasture‑based, non‑GMO feed, higher‑welfare, local—do you offer today, and what would it take for us to qualify?” In some northern EU regions, pasture milk contracts pay an extra one or two cents per litre in exchange for documented grazing days and limits on concentrates, while GMO‑free feed contracts can offer similar premiums if you can show full feed traceability. Not every farm can make those programmes work—but you don’t know until you ask.

4. How much are we relying on emergency support to balance our risk?

The last few years—Covid disruptions, energy price spikes—have shown that EU and national support schemes do appear when things get rough, but they can also be slow and administratively heavy. It’s sensible to argue for better policy. It’s risky to build your whole business plan on the hope that the next crisis cheque will land when you need it. So ask: “If prices were poor for the next two years and no new support arrived, what would we actually do—cut costs, change system, adjust scale, or something else?”

5. Who are we comparing ourselves with, and who can we be honest with?

Benchmarking and business clubs aren’t just a British thing. Chambers of agriculture, levy bodies like AHDB, and private consultants run groups where people share real numbers, not just coffee‑shop talk. In Wisconsin and Ontario, similar business‑focused producer groups have helped farms identify which changes actually move the needle in their systems. If you’re not part of any peer group like that, one practical 90‑day goal after reading this could be: find or form a small circle where you can put actual figures on the table and talk openly about strategy.

If you want a simple starting point for the next three months, it might look like this:

- Estimate your own compliance cost per 100 kilos.

- Have a direct conversation with your buyer about premium contract options and what it would take to join one.

- Commit to at least one meeting—formal or informal—where you compare real numbers with peers instead of just stories.

None of that changes Mercosur. But it does change how exposed—or how prepared—you are for the headwinds it adds to a game that was already getting tougher.

The Bottom Line

The EU–Mercosur deal isn’t going to change what your cows need tomorrow morning. Fresh cows still need careful handling through the transition period, calves still need feeding, and loans still need paying. What it does change is the wind you’re sailing in: a bit more pressure from low‑cost imports in a market where your costs are already high, and your support systems aren’t always fast or generous.

You can’t stop that wind. What you can do is understand it—and then decide what kind of boat you’re in, how you’re trimming your sails, and who you’re rowing with. In a world where none of us can afford to just drift, that’s where your real leverage lies.

Key Takeaways:

- “Modest” adds up fast: The Mercosur deal’s 30,000 tonnes of cheese and 10,000 tonnes of powder convert to about 345,000 tonnes of milk, like dropping the annual output of 550 EU family herds into an already flat market.

- The cost gap is real and structural: Rabobank shows New Zealand and Australia holding a roughly five‑cent‑per‑litre edge, while EU herds carry extra euros in slurry, emissions, welfare, and traceability costs that low‑cost competitors simply don’t pay.

- Mirror clauses sound fair, but won’t fix it: You can lab‑test cheese for residues—you can’t test it for stall dimensions or grazing days. Process standards are nearly impossible to enforce at the border.

- Mercosur lands where EU milk is already headed: With EU production flat at 149.4 million tonnes and more milk flowing into cheese and powders as fluid demand fades, the quota volumes compete exactly where margins are thinnest.

- Your best lever is knowing your own numbers: Farms that can pin down their compliance cost per 100 kg, push buyers on premium contracts, and benchmark honestly with peers will ride this headwind better than those waiting on Brussels to fix it.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- 4.23% Butterfat & $187,000 Gone: The Margin Math that Broke 2025 and Shapes Your 2028 – Stop guessing about your bulk tank’s true value. This breakdown exposes how tiny slivers of butterfat and protein either pad your bottom line or evaporate, giving you the blueprint to recapture lost margins before your next cheque lands.

- The Death of the Fluid Milk Market: What Every Producer Needs to Know – The fluid milk market is dying, and the global pivot to solids is accelerating. This strategy piece arms you with the long-range forecast to reposition your operation for the high-value component streams that will define dairy survival in 2028.

- Genetics in a Green World: Breeding for the Next Decade of Environmental Rules – Brussels isn’t backing down on environmental rules, but your breeding program can fight back. Discover how health-first genetic selection delivers the resilient, low-emission cow you need to thrive in a high-regulation, high-input trade environment.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!