In 2025, you’re spending 2,000–5,000 dollars per heifer. Are those cows really staying long enough to pay you back?

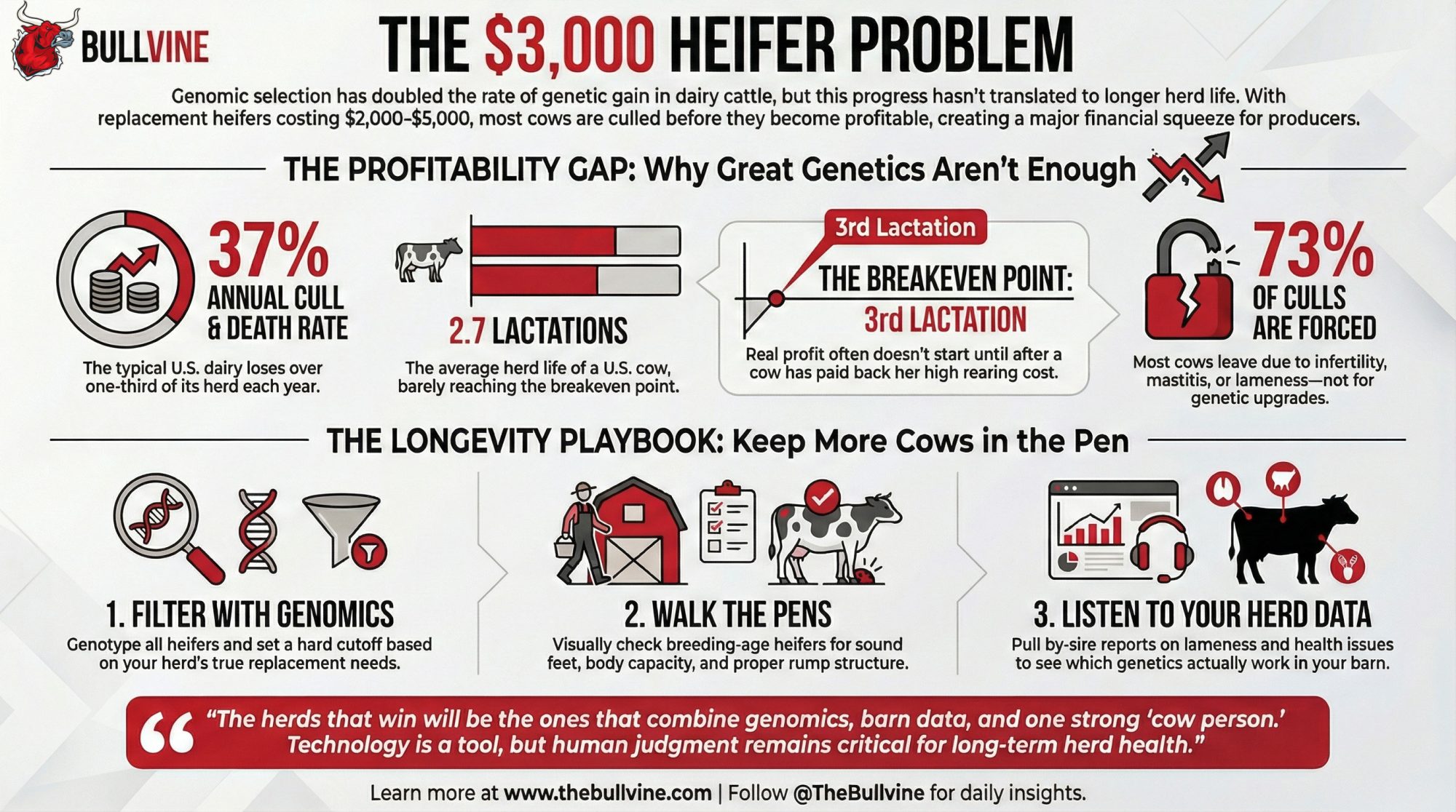

Executive Summary: Right now, genomics has doubled Net Merit genetic gain in U.S. Holsteins—from about 40 to 85 dollars per cow per year—but many herds are still watching cows leave at roughly 2.7 lactations, just as they finally start to repay 2,000–5,000 dollar heifer‑raising costs. NAHMS culling data and Penn State’s longevity work show combined cull‑plus‑death rates near 37 percent and confirm that, with today’s higher rearing costs, real profit often doesn’t begin until third lactation or later. At the same time, UW–Extension, Lactanet, and CoBank document rising heifer‑raising costs, a roughly 15–18 percent drop in U.S. replacement inventories, and 2025 replacement heifer prices that commonly top 3,000 dollars, with top animals over 4,000 dollars in some regions. The article argues that if you keep raising every heifer in that environment, the real problem isn’t your proofs—it’s your replacement strategy—and the missing piece is using genomics as a hard filter on which heifers deserve a stall, backed by a simple breeding‑age structural check on feet, heels, capacity, and calving structure. It then lays out a concrete playbook: genotype and set a clear cutoff tied to your true replacement needs, walk breeding‑age heifers once with structure in mind, use corrective mating only where it removes real structural risk, and pull by‑sire reports on lameness, fresh cow problems, and early culls so you’re not blindly trusting early genomic proofs. Finally, it looks ahead to tools like 3D BCS/weight and AI lameness detection and makes the case that, in 2025’s tight heifer and margin environment, the herds that win will be the ones that combine genomics, barn data, and one strong “cow person” to keep more cows walking the pens into their fourth and fifth lactations.

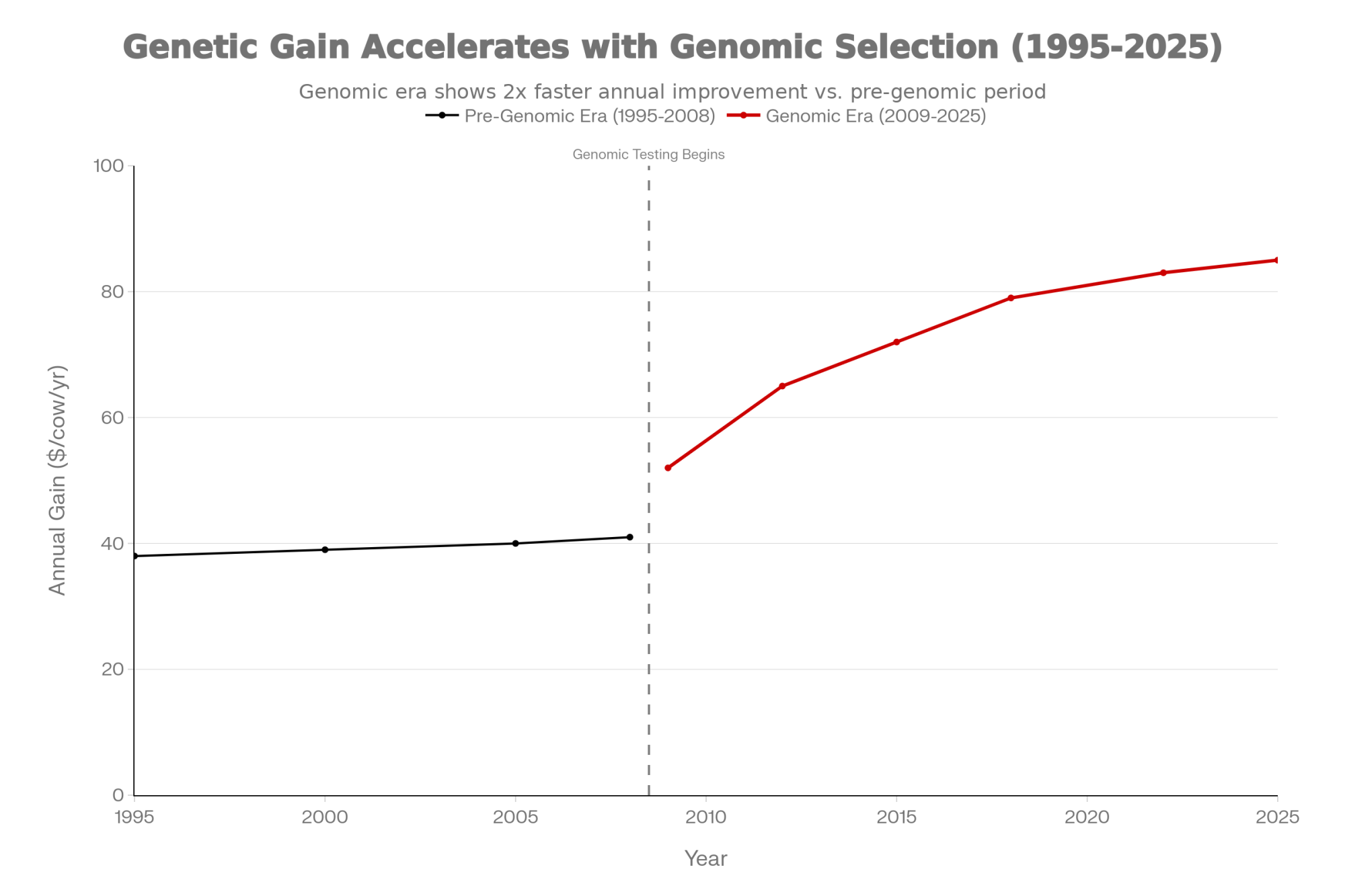

You know, when you look back over the last 15–20 years, it’s pretty wild what we’ve all lived through on the genetics side of dairy. Genomic testing has changed which bulls you pick, which heifers you raise, and how fast your herd moves genetically. Geneticist George Wiggans, PhD, with USDA’s Animal Genomics and Improvement Laboratory, and his co‑authors laid this out in a 2022 Frontiers in Genetics review: once genomic evaluations came in, the average annual increase in Net Merit in U.S. Holsteins essentially doubled—from about 40 dollars per cow per year in the five years before genomics to about 85 dollars per cow per year in the genomic era—and they clearly state that this “doubled the rate of genetic gain” in U.S. dairy cattle based on CDCB trend data across millions of animals.

What’s interesting here is that it wasn’t just more milk. A landmark analysis by Ana García‑Ruiz, PhD, and colleagues in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences dug into the U.S. national dairy database. It showed that once genomic selection was implemented, generation intervals for sires shrank from roughly 6.8 years to under 3 years in key sire pathways. The annual genetic gains for low‑heritability traits such as somatic cell score, daughter pregnancy rate, and productive life increased by four‑ to fifteen‑fold compared to the pre‑genomic era. They based that on decades of Holstein pedigree, genomic, and performance data across the national system.

So the data suggest genomics hasn’t just helped you chase production; it’s sped up progress in those “hard‑to‑move” traits many of us thought would take a whole career to shift. The problem is that a lot of that progress is still walking out the cull gate before it’s actually paid you back.

Looking at This Trend: What’s Actually in Net Merit Now?

Looking at this trend a bit closer, it helps to ask a simple question: what exactly are you selecting on today?

USDA’s most recent “Net merit as a measure of lifetime profit” revision, along with the Wiggans genomic selection review, makes it clear that U.S. dairy evaluations are now calculated for over 50 traits across production, fertility, health, calving, conformation, and efficiency. Net Merit pulls a large group of these into a single lifetime profit index using economic weights based on U.S. milk prices, feed costs, and culling patterns. That index includes milk, fat, and protein yields; several fertility traits such as heifer and cow conception rates and daughter pregnancy rate; cow and heifer livability; mastitis and other health traits; calving performance and stillbirth; age at first calving; a body‑weight composite; and feed efficiency via the Feed Saved trait, which uses body‑weight and residual feed intake data.

Over the last decade, USDA and the Council on Dairy Cattle Breeding (CDCB) have deliberately shifted the emphasis in Net Merit. When new health traits and Feed Saved were added, the economic weight on disease resistance and feed efficiency went up, while the weight on large body size was reduced because research showed that heavier cows require more maintenance feed and don’t necessarily return that cost in profit. Net Merit is now driven less by raw milk yield and more by health, fertility, and feed efficiency than it was in the early 2000s.

On the reliability side, invited reviews on genomic prediction in Holsteins report that genomic reliabilities for milk, fat, and protein in young bulls often sit in the 60–80 percent range when backed by a strong reference population, while fertility and health traits have lower reliabilities but are still significantly higher than the 20–30 percent levels typical of parent‑average evaluations. Those figures come from comparisons of genomic vs traditional proofs using large U.S. and Canadian datasets.

So, on paper, genomics and Net Merit give you a more complete, profit‑focused toolbox than we’ve ever had. And the genetic gains are real. The catch is that not everything you care about shows up on that proof sheet—and 2025 economics are unforgiving if cows don’t stay long enough to pay you back.

What Farmers Are Finding: Culling, Payback, and Short Careers

What farmers are finding, when they move from the proof sheet to the cull list, is that the picture gets uncomfortable pretty fast.

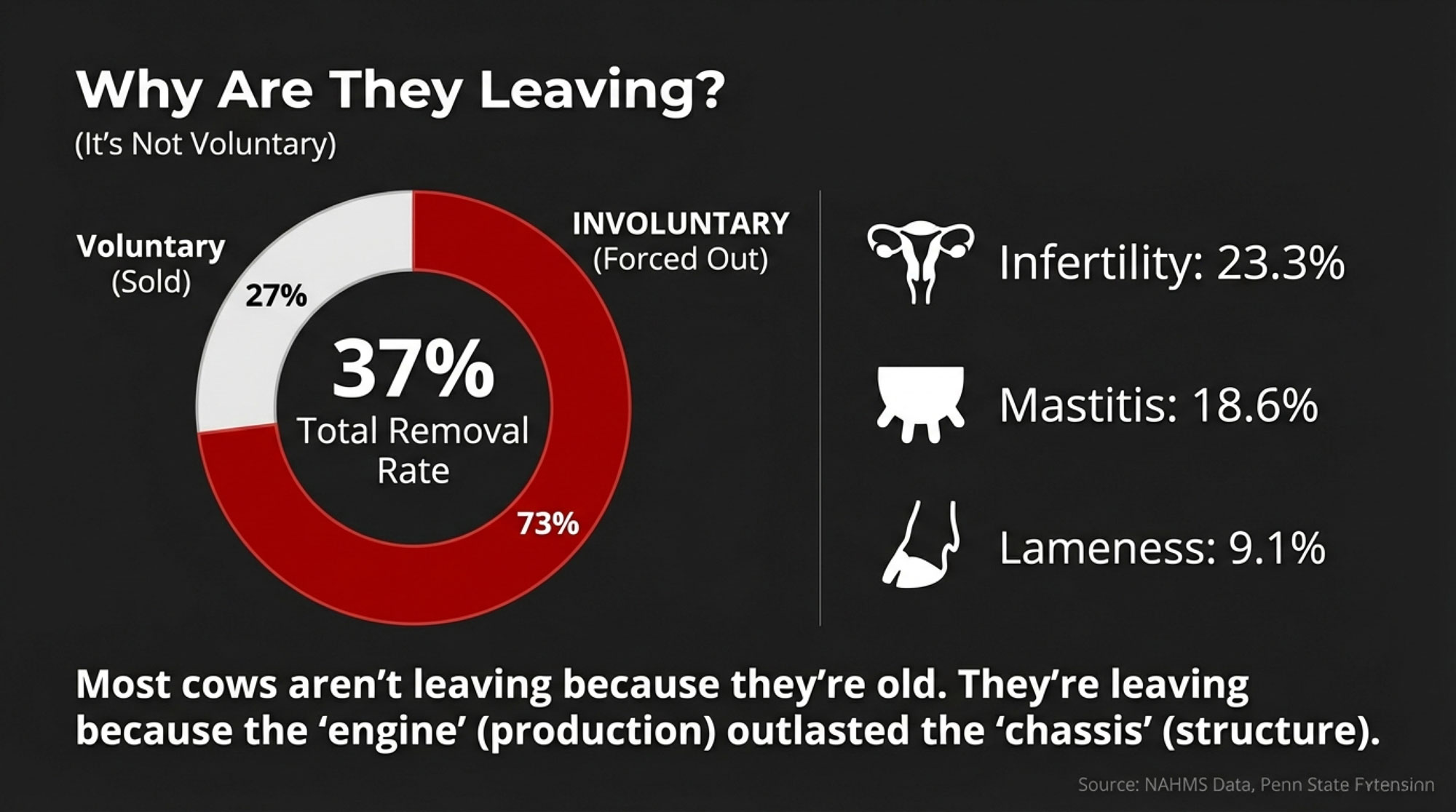

USDA’s National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS) 2024 data reports that the typical overall cull rate for U.S. dairies—counting death losses—is about 37 percent per year. That’s in line with the 2018 NAHMS survey in the Northeastern U.S., which documented an annual cull rate of 31.4 percent plus a 6.2 percent death rate, for a combined 37.6 percent removal rate. Penn State Extension’s “Cull Rates: How is Your Farm Doing?” uses those exact numbers as the benchmark.

When you look at why cows leave, the NAHMS data show that only 26.8 percent of removals in the Northeast were voluntary—cows sold for dairy or lower producers. The other 73.2 percent were involuntary, driven mainly by infertility (23.3 percent of removals), mastitis (18.6 percent), lameness (9.1 percent), and on‑farm deaths (6.2 percent). Penn State highlights these figures to emphasize that reproductive problems, udder health, and lameness remain the big three behind most culls.

| Removal Category | Share of Total Removals (%) | What This Means |

|---|---|---|

| Combined Annual Removal Rate | 37.0% | Cows + deaths leaving your herd every year (NAHMS, Northeast U.S.) |

| Voluntary Culls | 26.8% | Low production, dairy sales—you decided |

| Involuntary Culls | 73.2% | Forced exits—health, fertility, injury |

| └ Infertility | 23.3% | Cows that won’t rebreed on your timeline |

| └ Mastitis | 18.6% | Chronic udder health failures |

| └ Lameness | 9.1% | Foot/leg problems that won’t resolve |

| └ On-Farm Deaths | 6.2% | Metabolic disease, injury, sudden death |

So most cows aren’t leaving because they’re old, paid for, and you’re trading up. They’re leaving because something went wrong—often in the transition period or early in their productive life.

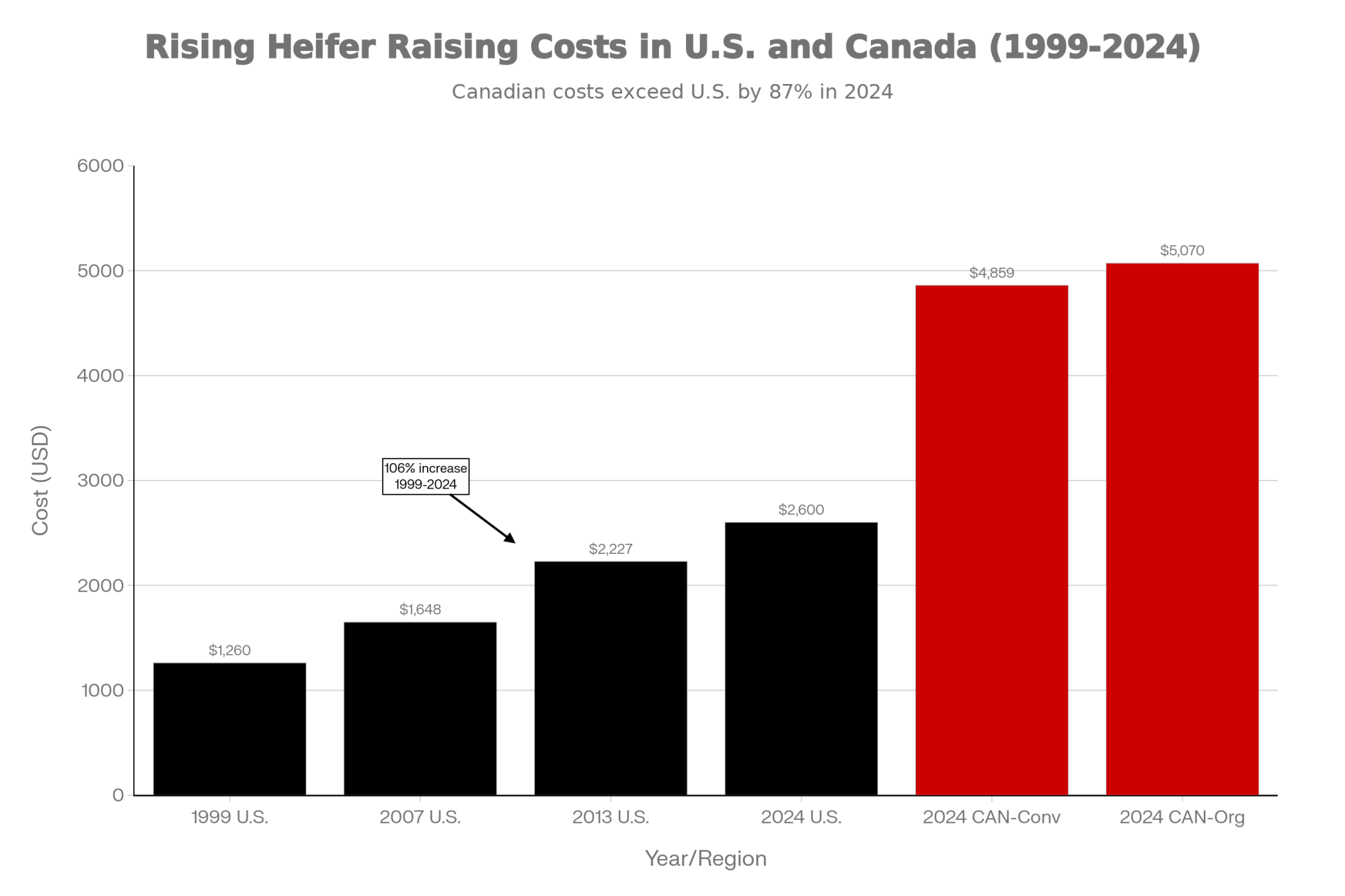

Now put that right next to the cost of raising replacements. A multi‑herd study from the University of Wisconsin–Extension calculated that the total cost to raise a replacement from birth to freshening averaged 2,227 dollars in 2013, not counting the calf’s initial value. That was up from 1,648 dollars in 2007 and 1,260 dollars in 1999, with feed as the largest single expense. The UW fact sheet “Heifer raising costs continue climbing upward” breaks down those costs and shows that feed alone accounted for over half the total.

More recent U.S. work hasn’t shown those costs going down. A 2025 article, drawing on Iowa State University Extension, reported that 2024 heifer‑raising costs in the Midwest were “just over 2,600 dollars” for a 24‑month heifer in many systems once you include feed, labor, housing, bedding, and overhead.

On the Canadian side, Lactanet’s “Analysis of the cost and value of dairy rearing programs” found that average rearing costs per heifer in Quebec were approximately 4,859 dollars for conventional herds and 5,070 dollars for organic herds, with a range from roughly 3,500 to over 7,000 dollars depending on housing, feeding, and management. Their 2023 follow‑up on the cost and profitability of rearing programs reinforces that rearing is a major capital commitment under supply management.

So generally speaking, you’re tying somewhere between 2,000 and 5,000 dollars into each heifer before she ever steps into the parlor, depending on where you are and how you raise them.

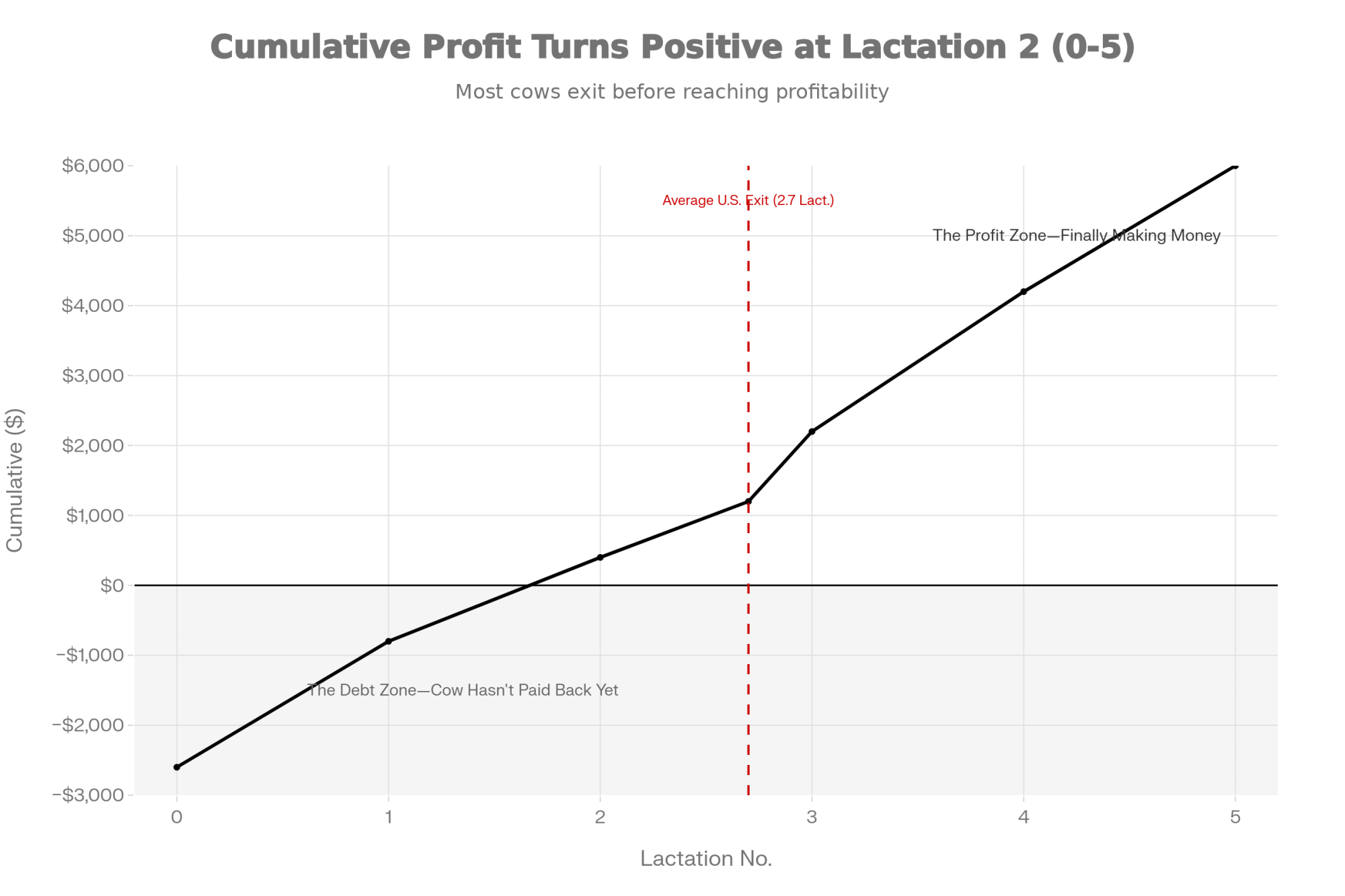

Penn State Extension took those rearing costs and asked a blunt question in their 2025 article “Have Your Cows Repaid Their Debts?” Their analysis, based on NAHMS data and economic modeling, shows that with current heifer‑raising costs, it often takes until at least the third lactation for a cow to repay her development cost. They also point out—citing NAHMS‑based summaries and regional data—that the average U.S. cow only stays in the herd for about 2.7 lactations and that many cows are culled by the end of their third lactation. Morning Ag Clips picked up similar points in a 2024 piece titled “How Long Do Your Cows Stay in the Herd?”, quoting extension specialists who warn that a large share of cows leave before they’ve yielded a strong return.

So the data suggest a tight squeeze: more expensive heifers, a payback point around three lactations, and an average cow productive life just shy of that. In a 2025 margin environment—where feed costs are still elevated, and component pricing is volatile—that’s a rough place to be.

If you run some simple numbers on a 200‑cow herd, the economic impact comes into focus. At a 37 percent cull‑plus‑death rate, you’re replacing roughly 74 cows per year. If you can move that combined rate down to 30 percent, you’re replacing about 60 cows. That’s 14 fewer heifers to raise. Using the documented U.S. cost range of 2,000–2,600 dollars per heifer, that’s 28,000–36,400 dollars per year in avoided heifer‑raising costs, before you even count the extra milk and butterfat performance from a higher proportion of mature cows. In Canadian quota herds, where Lactanet shows average rearing costs near 4,800–5,000 dollars, the same reduction in replacement needs could be worth 67,000–70,000 dollars annually.

| Metric | Baseline (37% Removal) | Improved (30% Removal) | Annual Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heifers Raised per Year | 74 | 60 | 14 fewer |

| U.S. Cost per Heifer | $2,600 | $2,600 | — |

| U.S. Total Rearing Cost | $192,400 | $156,000 | Saves $36,400 |

| Canadian Cost per Heifer | $5,000 | $5,000 | — |

| Canadian Total Rearing Cost | $370,000 | $300,000 | Saves $70,000 |

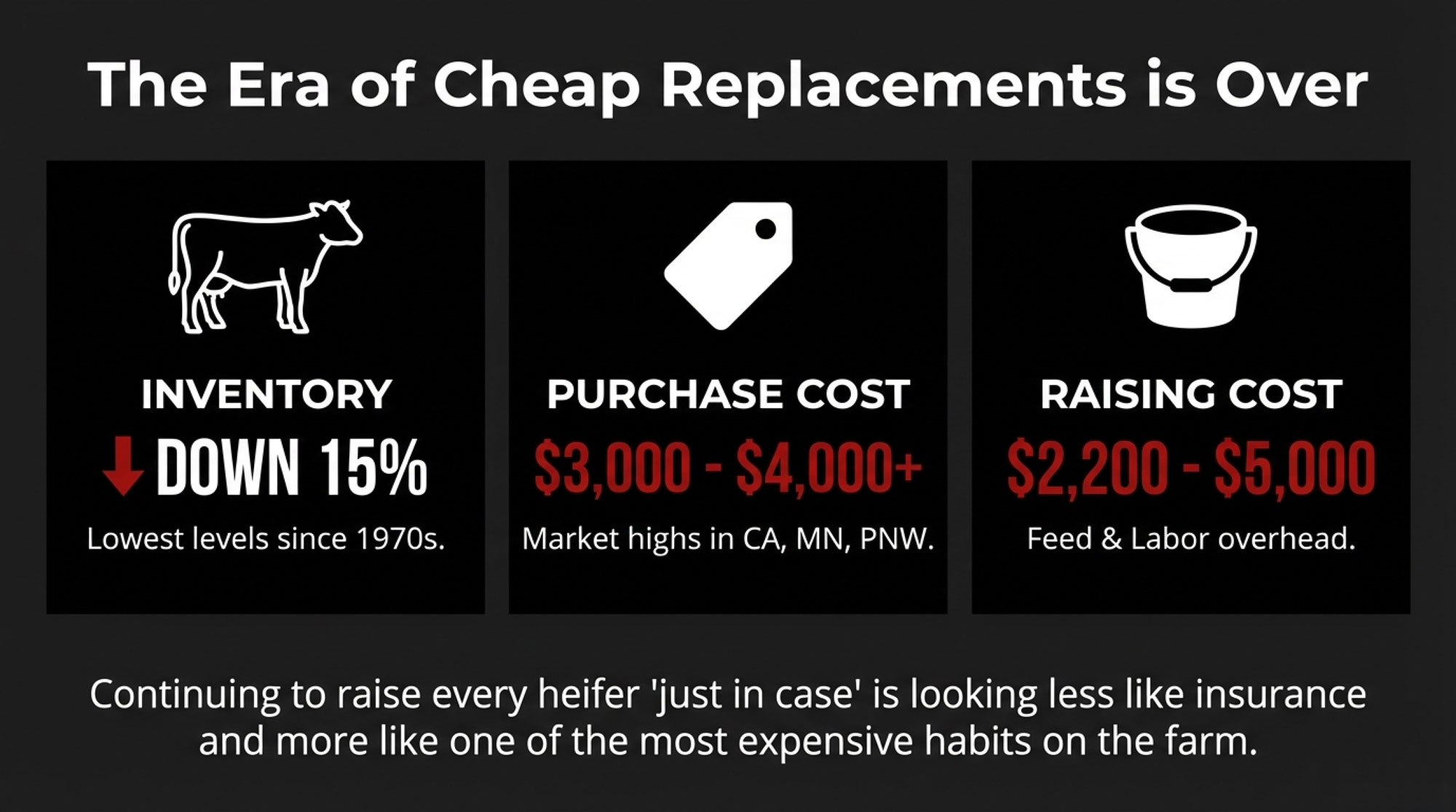

Here’s the thing I’ve noticed: once producers see that math with their own cull rates and rearing costs plugged in, continuing to raise every heifer “just in case” starts to look less like being conservative and more like one of the most expensive habits on the farm.

The Replacement Squeeze: Fewer Heifers, Higher Prices

As if the economics of raising replacements weren’t enough, the broader replacement market has been tightening the screws, too.

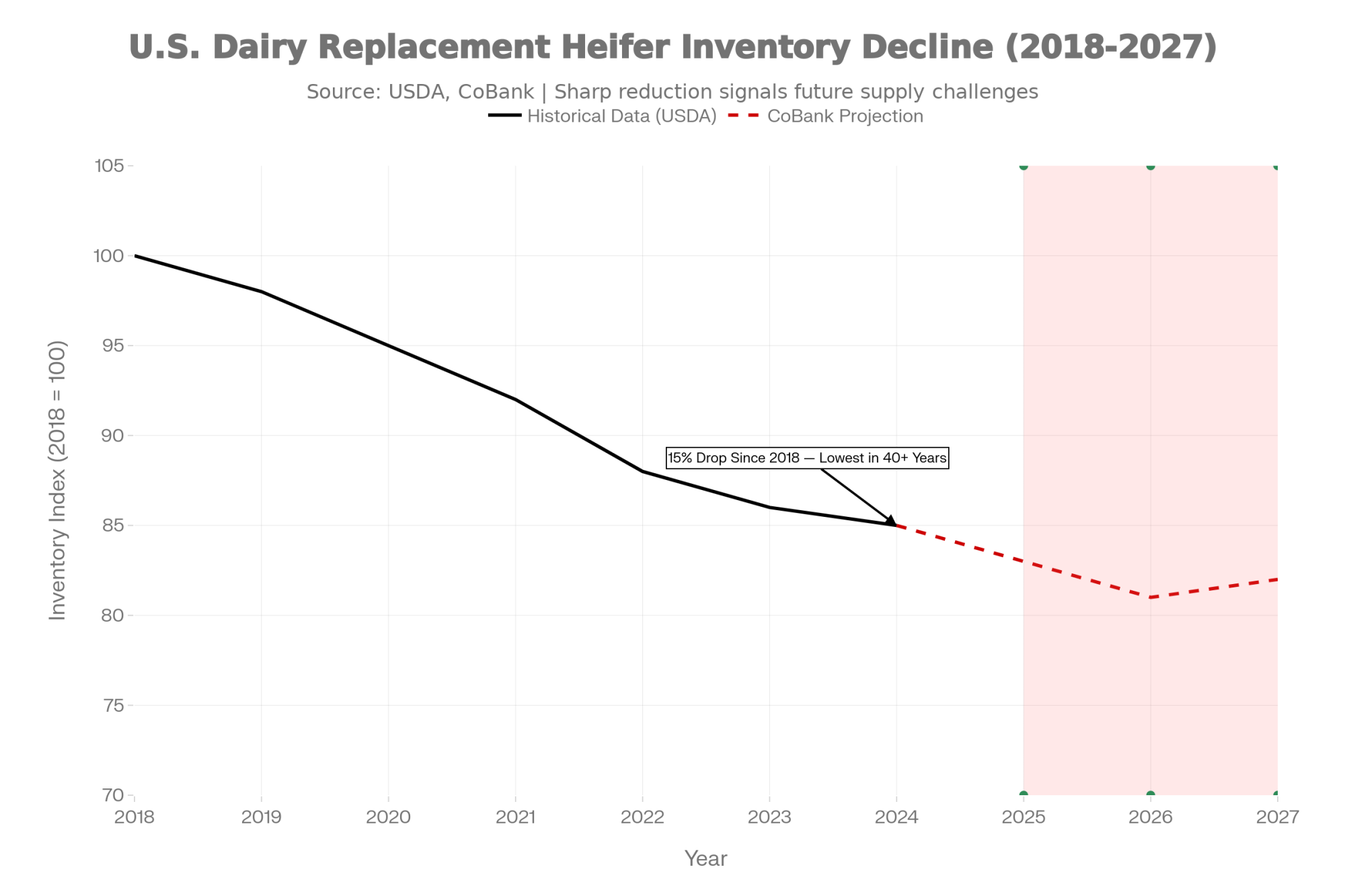

CoBank analysis of USDA cattle inventory reports shows that the number of dairy heifers weighing 500 pounds or more in the U.S. has fallen to its lowest levels in decades. CoBank’s 2025 analysis estimates about a 15 percent decline in dairy replacement heifer numbers over the past six years and notes that current inventories are at their lowest since the late 1970s. Their forecast suggests that heifer numbers will shrink further before beginning to rebound around 2027.

On the price side, market reporting describes multiple 2024–2025 sales where good Holstein replacement heifers routinely brought more than 3,000 dollars, with some top groups selling for over 4,000 dollars per head in California, Minnesota, and the Pacific Northwest. Market analysts have characterized current replacement heifer prices as “vaulting into record territory,” and these numbers align with both rearing costs and the tight national inventories reported.

So the data suggest that both raising and buying heifers are expensive right now, and that the industry as a whole doesn’t have a big surplus of replacements to fall back on. In a year when many herds are still feeling the aftershocks of 2025’s margin squeeze and processor pressure on components and quality, that makes your replacement strategy a high‑stakes business decision, not just a habit.

Structure, Environment, and Why Some Cows Don’t Make It to Third Lactation

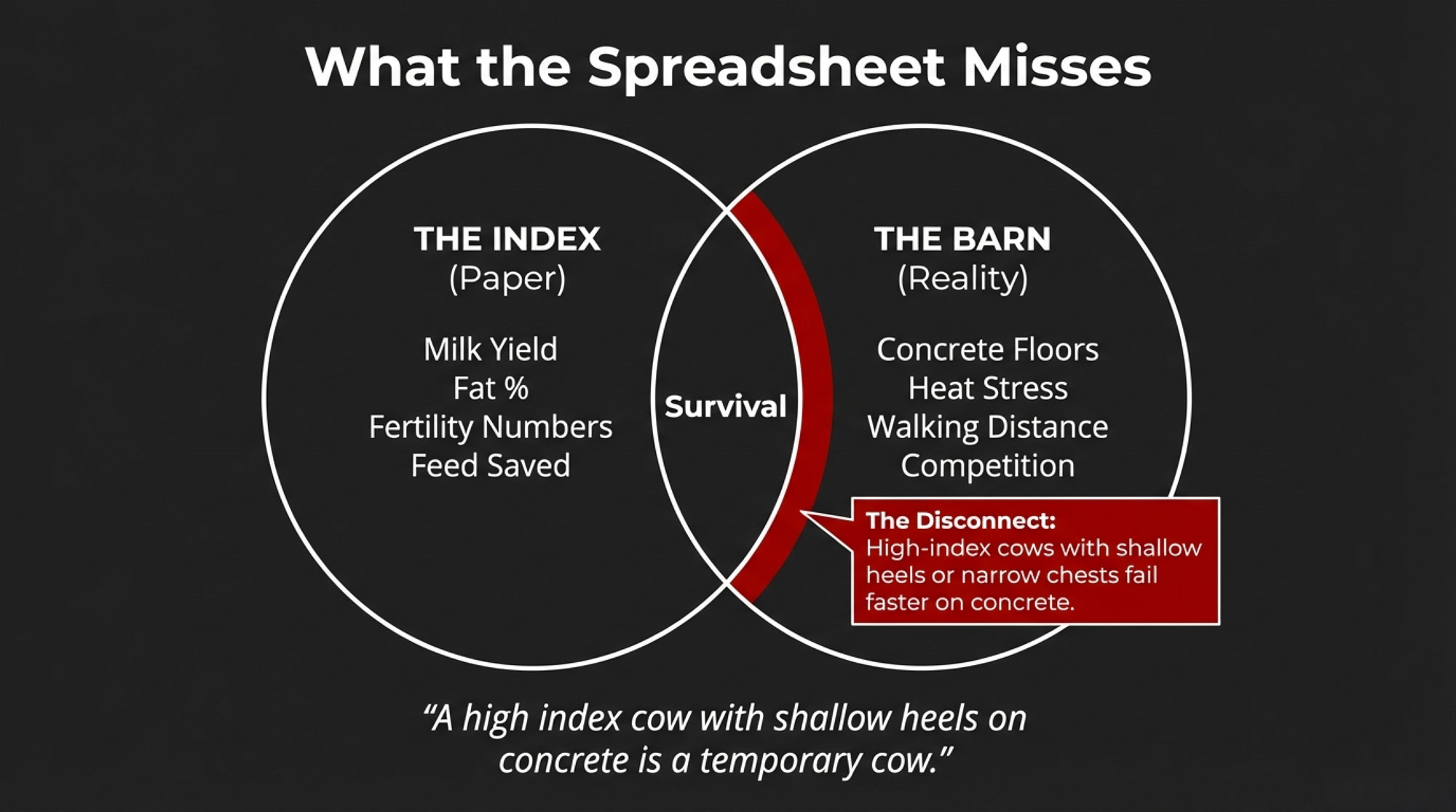

Looking at this trend from the barn floor, the piece that doesn’t fully show up in Net Merit or genomic reliabilities is structured cow health in your specific environment.

On the hoof‑health side, multiple studies published in the Journal of Dairy Science and other veterinary journals have shown that cows with shallow heel depth and low foot angle are at greater risk for claw horn lesions and lameness on concrete, especially in freestall systems with higher cow traffic. Those studies link shallow heels, weak rear feet, and poor claw conformation with increased incidence of sole ulcers, white line disease, and chronic lameness—conditions strongly tied to reduced milk production, poorer fertility, and higher culling risk.

On the metabolic side, transition‑cow reviews and field studies emphasize that low body condition score and insufficient dry matter intake around calving increase the risk of negative energy balance, ketosis, and displaced abomasum. That’s particularly true in high‑producing cows fed energy‑dense diets to maximize early‑lactation yield and butterfat performance. Research on late‑gestation heat stress has documented “programming” effects: dry cows exposed to heat during the close‑up period produce less milk and experience more health issues in the subsequent lactation; some studies have even found effects on daughters’ performance. This is especially relevant in dry-lot systems and Southern herds, where late‑gestation cows and heifers are walking longer distances in the heat.

In Wisconsin freestall herds, hoof trimmers and UW–Extension educators have commented—both in extension meetings and in trade articles—that daughters from certain sire lines with flatter feet and thinner heels show up more often in trimming lists and lameness treatments, even when those bulls look acceptable for feet‑and‑legs composites on paper. While those observations are anecdotal, they align closely with the published links between heel depth, foot angle, and the risk of claw lesions on concrete.

In Western dry lot systems in California and parts of the High Plains, producers often report that very tall, angular cows with lighter bone and less body capacity don’t handle long walks between lots and parlors in summer heat as well as medium‑sized, deeper‑bodied cows that hold condition better through the transition period. When you overlay those barn‑floor stories with the heat‑stress and transition‑cow research, the pattern makes sense: cows whose structure and metabolism aren’t well suited to that environment are more likely to end up as early culls, no matter what their genomic index says.

If you swing your attention to pasture‑based seasonal systems, you see a different set of pressures. Ireland’s Economic Breeding Index (EBI) and New Zealand’s national breeding goals have been built around cows that can walk, graze, maintain body condition, and rebreed on a tight seasonal schedule. Research from Teagasc and New Zealand spring‑calving herds shows that higher fertility, genetic merit, and better body condition scores are associated with improved reproductive performance, survival, and profitability in those grazing systems, while very large, high‑output Holsteins bred for North American TMR feeding often struggle to hold condition and pregnancy on grass.

All of that suggests that Net Merit and similar indexes capture part of the story indirectly—through traits like productive life, fertility, health, and body‑weight composite—but they can’t fully see how structure and environment interact in your particular freestall, tie‑stall, parlor, robotic setup, or grazing platform.

And this is where I’d say we run into a quiet myth: that as long as the genomic index is high, the cow will “work” anywhere. The data and the barns both say that’s not always true.

What Farmers Are Finding: How High‑Performing Herds Actually Use Genomics

What farmers are finding, especially those who’ve been in the genomic game for a while, is that the herds quietly pulling ahead tend to follow a three‑part pattern. They use genomics as a strong filter, they add a simple structural check at the right time, and they let their own herd data tell them when a bull isn’t working in their environment—even if his proof still looks good.

1. Let Genomics Decide Who Deserves a Stall

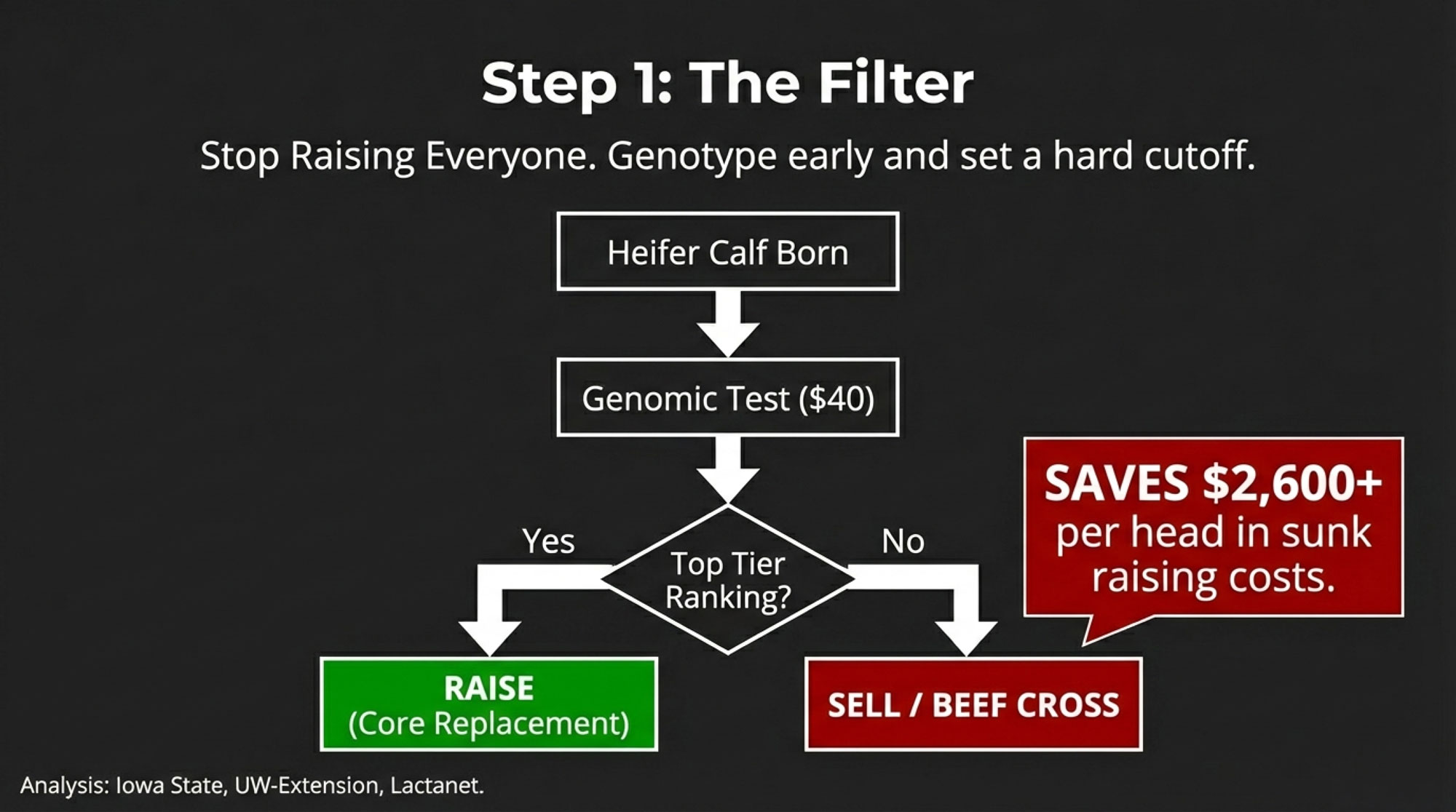

First, they use genomics to decide which heifers even get to compete for a stall.

In many progressive Midwest and Northeast operations, every heifer is genotyped between three and six months of age. CDCB reports that hundreds of thousands of female dairy cattle are genotyped every year, and case studies profile farms that use whole‑herd genotyping to drive their replacement and beef‑on‑dairy strategies.

The pattern in those herds often looks like this:

- Genotype the heifer group. All heifers—or at least all heifers from core cow families—get tested.

- Rank on a profit index. Heifers are ranked on Net Merit in the U.S. or Pro$/LPI in Canada, and key functional traits—daughter fertility, productive life, mastitis resistance, calving traits, body size—are checked against herd goals.

- Set a clear cutoff. An internal threshold is set based on how many replacements the herd truly needs annually, not “everything that hits the ground.”

- Sort replacements vs beef. Heifers clearly below that line are designated for beef‑on‑dairy matings or other marketing paths instead of being automatically raised as core replacements.

Economic analyses from Iowa State, UW–Extension, and Lactanet all support this kind of triage. If genotyping costs around 40–50 dollars per heifer and the information lets you avoid raising 10–15 low‑merit animals that would each cost 2,000–2,600 dollars in the U.S. or 4,800–5,000 dollars in Canada, you’re avoiding 20,000–75,000 dollars of future rearing costs for a testing investment of maybe 4,000–7,500 dollars. Iowa State’s heifer‑inventory work and Lactanet’s rearing‑cost modeling both illustrate this scale of impact.

A lot of herds then pair this with beef‑on‑dairy. Extension surveys and industry reports from Iowa State, Kansas State, and High Plains fieldwork confirm that using beef semen on lower‑merit dairy cows and heifers has become a common way to add value to non‑replacement pregnancies and concentrate dairy replacements among the top genomic group. ROI analyses show improved calf value and better alignment between replacement supply and milk‑herd needs when this is done with clear genomic cutoffs.

Under the Canadian quota, Lactanet’s rearing‑program analysis and their work on cost and profitability emphasize that cows must stay in the herd long enough to repay higher rearing costs and generate a return on quota. Their numbers show average rearing costs around 4,800–5,000 dollars per heifer and a wide variation in cost per litre associated with heifer inventory, age at first calving, and productive life. Many Canadian advisors use those figures to support the rule of thumb that cows generally need three or more lactations to generate strong returns under quota.

So the first big step that successful herds have taken is to let genomics decide who deserves the chance to become a cow, instead of raising every heifer and hoping it works out. If you’re still raising every heifer in 2025, this development suggests you’re tying a lot of capital up in animals that will never pay you back.

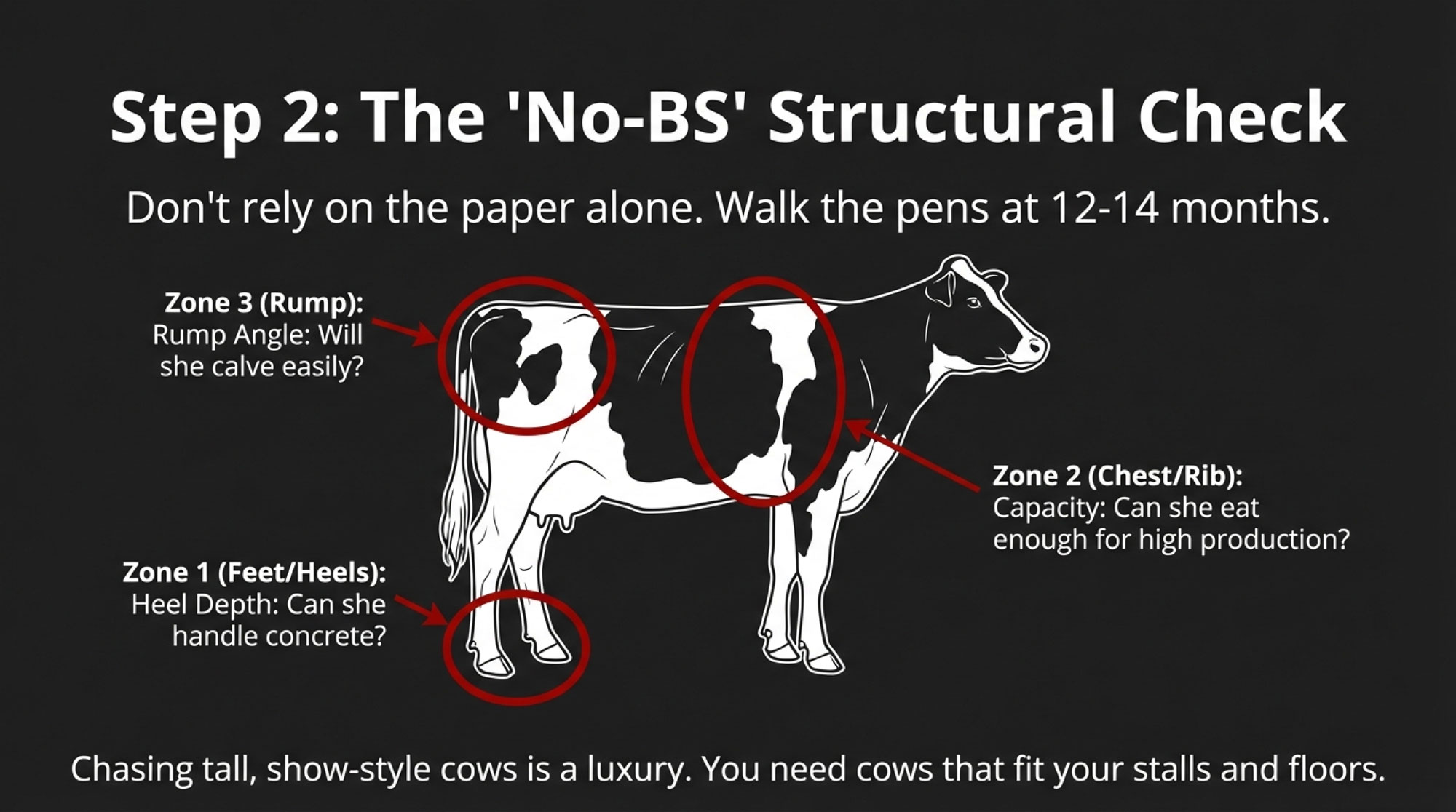

2. Walk the Pens Before First Breeding

Second, the herds that are combining genomics with longevity add a simple structural check at breeding age.

Usually, that’s around 12–14 months for Holstein heifers in freestalls or tie‑stalls, and a bit later for seasonal grazing herds that breed heifers to fit a calving block. Someone—often the breeder, herd manager, or an experienced employee—walks through the breeding‑age pens with a few key questions in mind:

- Compared to the older cows that come through the transition period well in this herd, does this heifer have enough body depth and chest width to eat what she’ll need on the diets and in the facilities you actually have?

- Do her feet and heels look comparable to the heifers and cows that stay sound on your floors and paths, or are they noticeably flatter and weaker?

- Does her rump and hip structure look like it will help or hinder calving and day‑to‑day movement in your barns or on your laneways?

Lameness research has tied shallow heels and low foot angle directly to higher odds of claw lesions and lameness on concrete, and transition‑cow research has linked limited intake and low body condition around calving to higher metabolic disease risk and weaker early‑lactation performance. Those are exactly the kinds of problems that drive early culling and drag down fresh cow management.

In a 70‑cow tie‑stall in Quebec, this might mean flagging just a few heifers as “structural concerns” and thinking about different mating or marketing plans for them. In a 400‑cow freestall in Wisconsin or an 800‑cow dry lot system on the High Plains, some producers have built simple 1‑to‑3 scoring systems and trained staff to mark heifers with clear structural issues during routine handling, then revisit that list when making breeding decisions.

Chasing tall, show‑style cows in freestalls or dry lots can be a costly luxury if they don’t walk and last. The herds that are winning on both banners and bank accounts are the ones that match their type to their environment rather than copying someone else’s ideal.

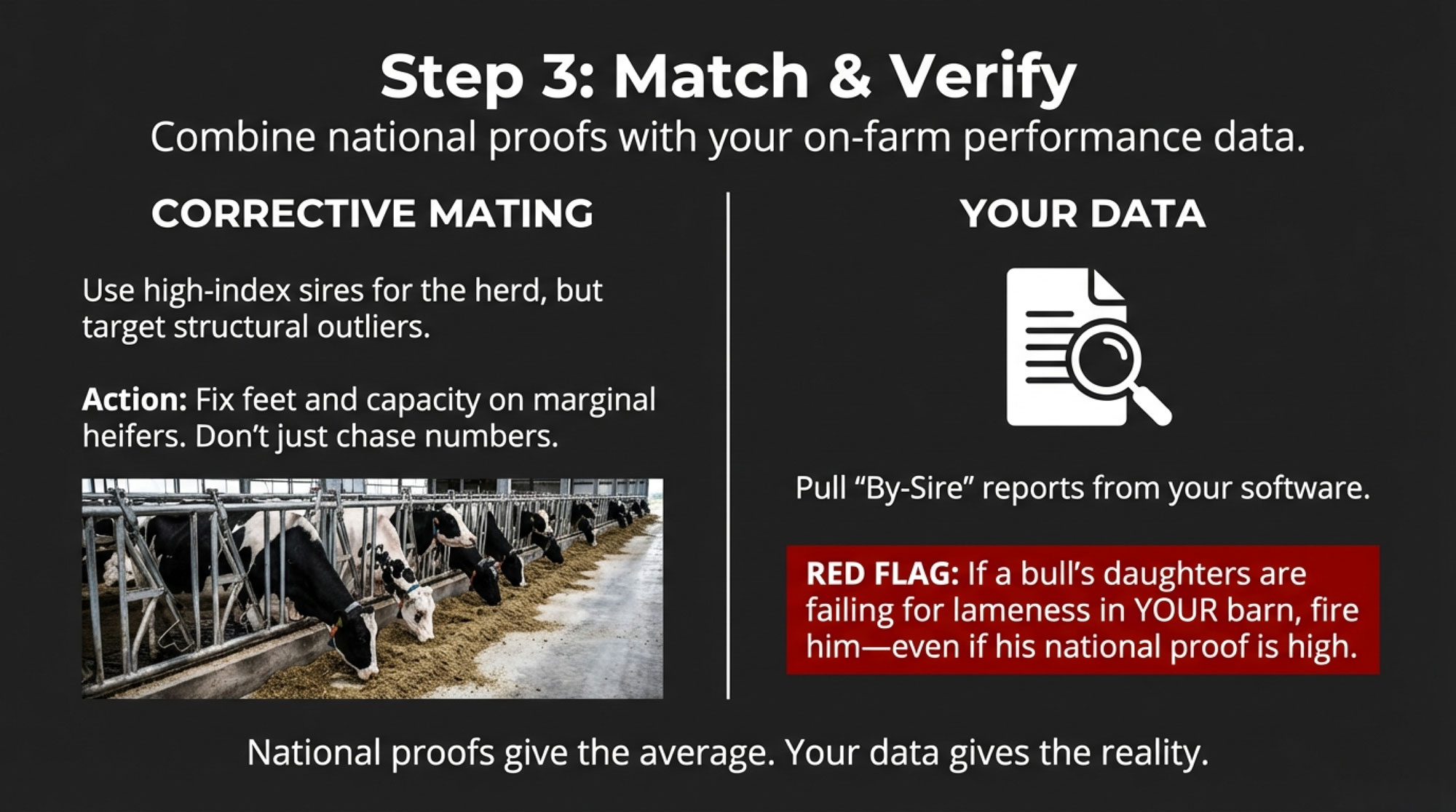

3. Use Corrective Mating Where It Really Pays

Third, these herds use corrective mating selectively, focusing on the animals where it’s most likely to pay off.

For the majority of cows and heifers—the ones that clear both the genomic filter and the structural walk—they keep breeding plans straightforward. They choose high‑index sires based on Net Merit, Pro$, or LPI that are solid for daughter fertility, livability, mastitis resistance, calving ease, and feet and legs, and they avoid bulls that are extreme for body size, or that carry trait weaknesses that clearly don’t fit their barns. USDA’s Net Merit documentation and our own Bullvine articles on genetic tools both suggest that letting multi‑trait economic indexes handle most of the weighting is a sound base strategy, as long as you pay attention to a few critical traits for your system.

For the smaller group of structurally marginal heifers, they still use good bulls—just more carefully. On narrower, shallow‑bodied heifers, they’ll lean toward bulls that are known to add strength and capacity without giving up too much on profit. On heifers with flat, thin‑heeled feet in concrete or dry lot systems, they’ll favor bulls with strong feet‑and‑legs evaluations and, where available, better claw‑health and locomotion scores. On heifers with awkward rumps, they reach for sires with more functional rumps and better daughter calving ease.

Herd‑level evaluations and extension case studies suggest that trading 50–100 dollars of index on these specific matings can be worthwhile if it reduces early structural culls and improves fresh cow management, especially when you look at lifetime milk and component yield instead of just first‑lactation performance.

Raising every heifer and then breeding them all to the same top‑index bull might feel simple. In 2025, it’s also a good way to waste both semen and stall space.

| Step | Action | Financial Impact |

| 1. The Filter | Genotype and set a hard cutoff. | Avoids $2,600+ in costs for “low-merit” calves. |

| 2. The Walk | Visual check for feet, capacity, and rump. | Reduces involuntary culls in 1st/2nd lactation. |

| 3. The Match | Corrective mating for structural outliers. | Ensures the best genetics actually survive to pay back debt. |

Looking at This Trend from Your Own Records

There’s one more piece that high‑performing herds have learned to lean on, and that’s their own herd data.

Geneticists working on the U.S. genomic system have been clear that even with high average reliabilities, individual genomic bulls—especially the young, high‑ranking ones—can move once daughters calve across a range of environments. That point appears in Wiggans’ work as well as in invited reviews on breeding goals and selection strategies.

What farmers are finding is that by‑sire reports from their own herd management software are one of the best early warning systems they have. The pattern usually looks like this:

- Once or twice a year, they pull reports that show lameness events, hoof‑trimmer findings, fresh cow problems (ketosis, DA, metritis), calving difficulty, and early culls by sire.

- They compare each sire’s daughters to herd baselines: if daughters from one bull show significantly higher rates of lameness, fresh cow treatments, calving issues, or early culls, that bull moves onto a “caution” list.

- They dial back that sire’s usage, especially in heifers, and watch how his official proofs move in the next couple of evaluation runs.

Extension educators and consultants in the Northeast, Midwest, and West have highlighted farms that do this, and their experiences align with what geneticists recommend: use national proofs for the big picture and your own data for local calibration.

In Western dry lot and Southern herds, some producers are also starting to sort these problem lists by calving season and sire to see whether certain bulls’ daughters struggle more when they calve into heavy heat. Research on late‑gestation heat stress suggests that cows calving after hot, dry periods may be at higher risk of poor performance and health problems. A few herds are using that insight to adjust which bulls they use on cows expected to calve in the hottest windows.

So here’s a fair question: do you know, off the top of your head, which bulls sired your last 20 early culls or your worst fresh cows? If the answer is no, your herd software probably does—and it’s worth asking.

New Tools Coming: 3D Cameras, AI Gait, and Why People Still Matter

Looking out a few years, it’s pretty clear that technology is going to keep adding tools to this mix.

Several recent studies and technical articles have evaluated three‑dimensional camera systems that estimate body weight and body condition score automatically from overhead images. These systems use depth sensors and algorithms to reconstruct the cow’s shape and have shown good agreement with scale weights and experienced BCS scorers in research settings and early commercial trials.

At the same time, dairy tech companies and research groups have been developing automated lameness detection systems that use cameras, accelerometers, or pressure mats with AI‑based gait analysis. Peer‑reviewed studies and industry case reports document systems that can detect subtle gait changes before cows are obviously lame, with high sensitivity and specificity. That kind of early warning can help target hoof trimming and fresh-cow management, and reduce the severity and cost of lameness cases.

Some research teams are already experimenting with combining these high‑frequency phenotypes—weight, BCS, locomotion, rumination—with genomic information to improve predictions for traits like resilience, feed efficiency, and long‑term health that are hard to measure at scale today. A 2024 bibliometric review on genomic selection in animal breeding and recent overviews of bovine genomics highlight this as a major emerging direction.

This development suggests that, in the future, we may be able to quantify and select for “resilience” and “structural soundness” more objectively. That’s exciting, especially for larger herds that need help catching subtle changes in body condition, movement, and fresh cow behavior.

But even as these tools roll out, every one of them still needs a human in the loop. Someone has to review the alert, examine the cow, and decide whether the system’s flags match reality. Judging coaches, classifiers, and long‑time herd managers have been saying for years that as our industry has gotten better at reading proofs and genomic reports, fewer people have had deep training in reading cows—feet, legs, capacity, udders, and how cows handle the transition period in real barns. Workshops and classifier training materials echo that concern.

From what I’ve seen, the herds that are making the most of genomics and new tech are the ones that still have at least one strong “cow person” in the mix. That person can look at a genomic report, look at a heifer, look at the hoof‑trimmer’s notes, and connect those dots. In 2025, when capital is tight and processors are picky, that skill might be as valuable as any piece of hardware you can bolt into the barn.

What To Do This Year: A Short List

If you’re thinking, “Okay, what do I actually do with all this?”, here’s a short, practical list based on the data and what successful herds are doing:

- Genotype the heifers you’re serious about and set a real cutoff.

Test all heifers or at least those from your best cow families. Rank on Net Merit or Pro$/LPI, check fertility, productive life, mastitis, calving traits, and size, then draw a line based on how many replacements you truly need. Heifers below the line become beef‑on‑dairy or are marketed differently, instead of automatically being raised. - Walk your breeding‑age heifers once with structure in mind.

Before first breeding, take one good look at body capacity, feet and heels, and rump structure, comparing heifers to the cows that last in your herd. Use what we know about lameness and transition‑cow risk to flag structural outliers that are more likely to become expensive early culls. - Use corrective mating where it matters most.

For structurally marginal heifers, pick high‑merit sires that also bring better feet, legs, capacity, or calving traits—even if it means giving up a bit of index on those matings. For the rest, let multi‑trait indexes do the heavy lifting and avoid extremes that don’t fit your facilities or fresh cow management reality. - Pull one by‑sire problem report this year.

Use your herd software, vet records, and hoof‑trimmer logs to see which sires’ daughters show up more often in lameness events, fresh cow treatments, calving problems, or early culls. If one bull looks worse than the herd average, dial back his usage and watch how his proof moves in coming runs. Doing nothing with this information is also a strategy—and in 2025, it’s one of the riskiest ones you can pick. - Start planning how you’ll use new tech, but keep people at the center.

If you’re considering 3D cameras or lameness‑detection systems, think about who on your team will own those alerts and how you’ll use that data alongside genomics and good old‑fashioned pen walking. The tech can sharpen your view, but it won’t replace judgment.

The Bottom Line

So, looking at this trend as a whole, the data and the barns are pointing in the same direction.

The herds that are quietly getting ahead aren’t “all genomics” or “no genomics.” They’re the ones that:

- Use genomic tests and economic indexes to decide which heifers truly deserve a place in the replacement pipeline, instead of raising every calf and hoping it works out.

- Bring a straightforward, honest look at structure into the picture at breeding age to make sure those heifers’ bodies fit their stalls, floors, and walking distances.

- Use corrective mating where it actually pays—on the smaller group of structurally marginal animals—while letting Net Merit or Pro$/LPI guide most matings.

- Listen to their own herd data on bulls and adjust usage when their cows tell a different story than early proofs suggest.

- And keep at least one strong “cow person” in the mix to connect what the numbers say with what’s happening in the pens, especially through the transition period and fresh cow management.

You’re already paying for genomics. You’re already paying a lot to raise replacements. Either you use genomics, structure, and herd data together to keep more cows past three, four, or five lactations—or you keep pouring 2,000–5,000 dollars into replacements that walk out just as they reach breakeven.

What’s encouraging is that you don’t need to overhaul everything overnight. Testing a few more heifers, drawing a firmer line on who you raise, walking one heifer group with structure in mind, and pulling one by‑sire problem report this year can start nudging your herd in the direction the data—and the best herds—are already heading.

Key Takeaways

- Genomics doubled genetic gain—but not cow longevity. Net Merit now climbs about 85 dollars per cow per year versus 40 dollars pre‑genomics, yet the average cow still exits around 2.7 lactations—often before paying back her 2,000–5,000 dollar raising cost.

- Most culls aren’t planned—they’re forced. NAHMS data show a 37 percent combined cull‑plus‑death rate, driven by infertility, mastitis, and lameness. Penn State’s analysis confirms real profit typically doesn’t start until the third lactation or later.

- Raising every heifer is now a high‑cost gamble. U.S. replacement inventories have dropped roughly 15 percent to multi‑decade lows, and 2025 heifer prices commonly exceed 3,000 dollars. “Just in case,” heifer programs may be your most expensive habit.

- Top herds treat genomics as a filter, not a trophy. They genotype early, set a hard cutoff tied to true replacement needs, walk heifers at breeding age for structural fit, and use corrective mating only where it actually reduces cull risk.

- Your own herd data can catch what the proofs miss. Pull by‑sire reports on lameness, fresh cow problems, and early culls at least once a year—bulls whose daughters don’t hold up in your barns will show up there before proofs fully adjust.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The $4,000 Heifer: Seven Strategies to Navigate the New Dairy Economy – Reveals seven concrete tactics to survive the $4,000 heifer era, from leveraging precise genomic cutoffs to recalibrating beef-on-dairy percentages. It arms you with immediate management changes to stop the cash-flow bleed and protect your replacement pipeline.

- 438,000 Missing Heifers. $4,100 Price Tags. Beef-on-Dairy’s Reckoning Has Arrived. – Exposes the structural deficit of 438,000 missing heifers that will dictate dairy margins through 2028. It delivers a long-term positioning strategy for navigating record-high replacement prices and the narrowing window of processor leverage.

- Digital Dairy Detective: How AI-Powered Health Monitoring is Preventing $2,000 Losses Per Cow – Breaks down how AI-powered health monitoring replaces reactive “firefighting” with proactive precision, identifying metabolic issues 120 hours before clinical signs. It gives you the technological advantage to keep high-genetic-merit cows productive into their fourth lactation.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!