Two dairies. Same carbon practices. One makes $150K, the other makes $3K. The difference isn’t what you think.

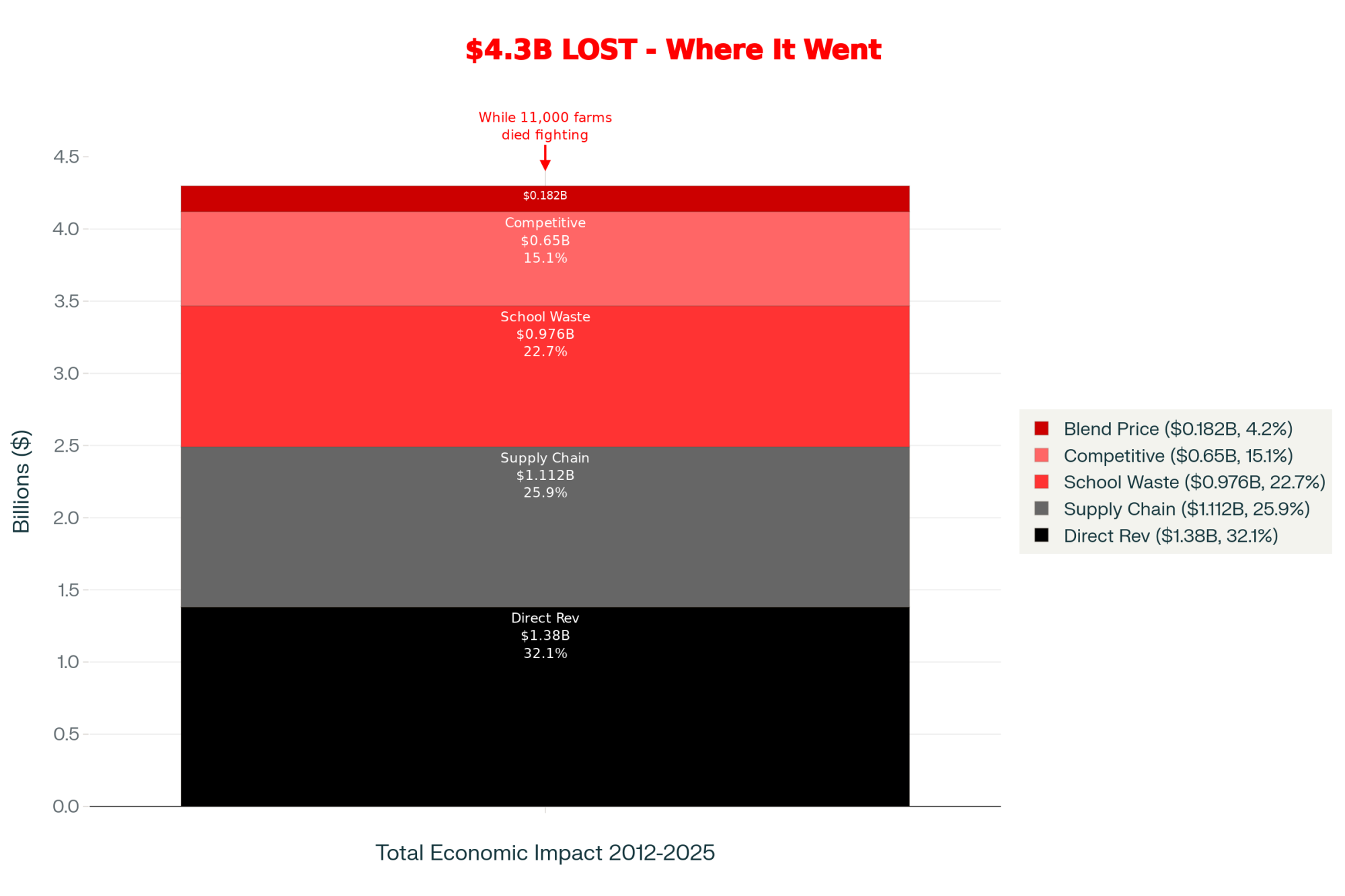

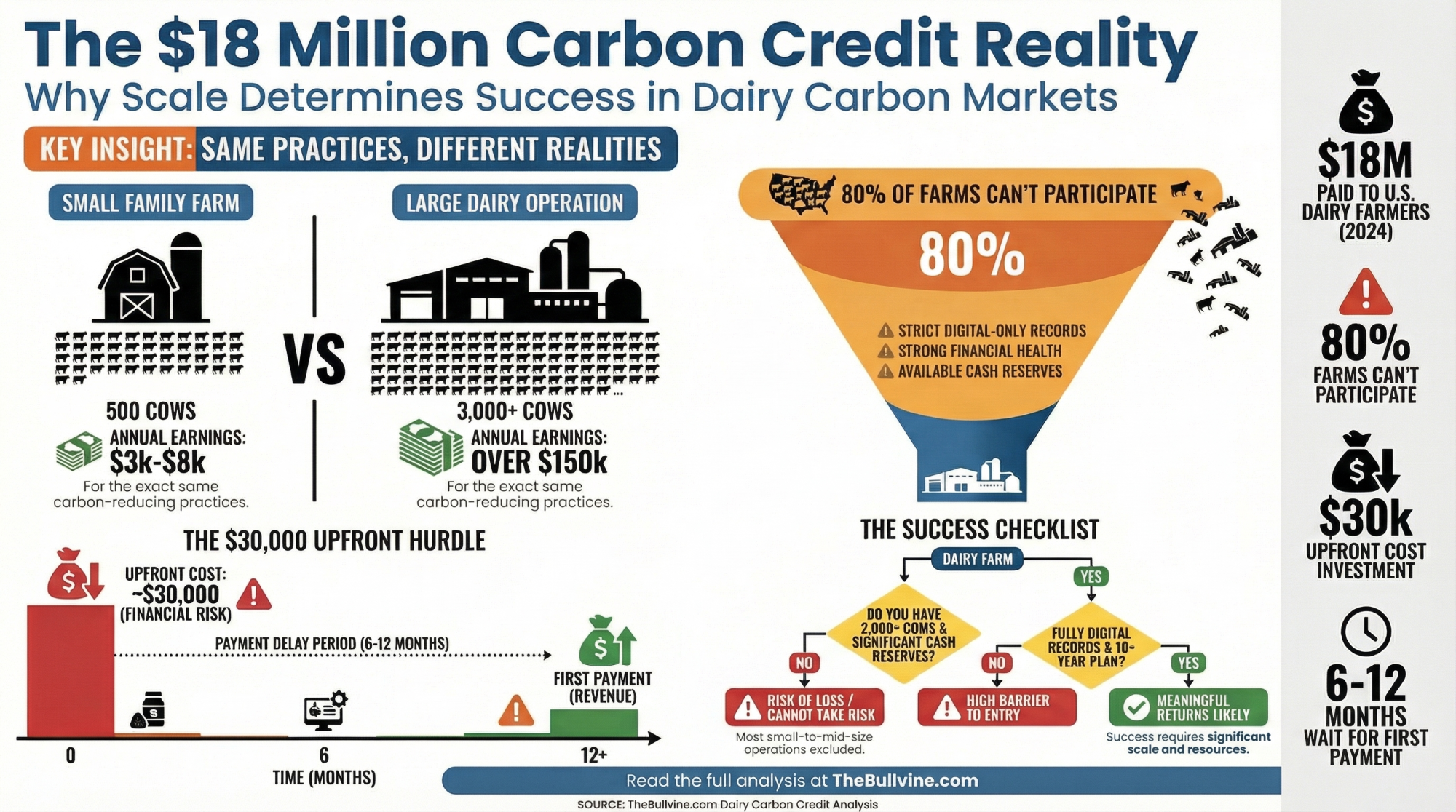

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Athian paid dairy farmers $18 million for carbon reductions in 2024, but the money isn’t flowing where you’d expect—large farms pocket $150,000 yearly while small operations get just $3,000 for identical practices. The math explains why: although per-cow profits are similar at $40-56, only operations with 2,000+ cows can justify the $28,000-37,000 upfront investment and 6-12 month payment delays. Add requirements for digital records and working capital above 1.25, and 80% of U.S. dairy farms simply can’t participate. Yet for qualified operations, carbon credits offer genuine value—transforming feed additives you’re already considering into profit centers. This article delivers real economics, explains why scale wins again, and provides a practical framework for determining whether carbon credits make sense for your specific operation.

So I was reviewing Athian’s latest announcement the other day, and here’s what caught my eye—they’ve actually distributed million to dairy farmers for emissions reductions since early 2024. Not promises, not projections. Real checks hitting real farm accounts. And what’s interesting is, these are for practices many of us have been considering anyway for operational efficiency. You know how it is—in our industry, sustainability initiatives usually mean spending more money for the privilege of doing the right thing. This development, though, it deserves our careful attention.

I’ve been talking with producers from Vermont to New Mexico who’ve navigated these dairy carbon credit programs, and I’ve noticed a fascinating pattern emerging. Success varies dramatically across operations, and here’s what might surprise you—it’s not about environmental commitment or willingness to adapt. What I’ve found is it’s primarily about operational scale, cash flow position, and whether you’ve already got your data management systems dialed in.

Understanding the Market Forces at Play

Let’s talk about what’s really driving these payments. As many of us have seen, major food companies—Nestlé and Mars among them—have committed to reducing supply chain emissions by 30% before 2030, according to their recent sustainability reports. And here’s the thing: since most of their carbon footprint originates at the farm level rather than in processing facilities, they’re actively seeking verified reductions from us dairy suppliers.

This has led to something called “insetting”—basically, these companies are investing in emissions reductions within their own supply chains rather than buying random offset credits from who knows where. DFA pioneered this approach in January 2024, becoming the first U.S. cooperative to purchase verified livestock emissions reductions through Athian’s platform. Their initial transaction involved a Texas dairy using Elanco’s Experior technology, and they documented 1,150 metric tons of CO2 equivalent reduction. That’s not theoretical—it’s verified, third-party audited through SustainCERT standards, and most importantly, paid for.

What distinguishes this from all those previous carbon initiatives we’ve seen come and go? The verification rigor. These dairy carbon credit programs require comprehensive documentation—you’re matching feed invoices with ration records, integrating milk production data, running everything through standardized calculation models, and having independent auditors verify it all. This level of verification means buyers can confidently report these reductions to their stakeholders.

Current Practices Generating Returns

Looking at current market activity, four practice categories are demonstrating consistent value for dairy farm profitability, and each has distinct operational requirements and economics worth understanding.

Feed additives for enteric methane reduction have really emerged as the primary pathway. Bovaer—that’s the 3-nitrooxypropanol compound from DSM-Firmenich—got regulatory approval in Canada and the UK in January, and the FDA completed their review in May. What’s encouraging is the research consistency: across 56 peer-reviewed studies, we’re seeing approximately a 30% reduction in enteric methane when administered at recommended doses. According to the Journal of Dairy Science’s comprehensive analysis, this translates to a 10-15% reduction in overall GHG intensity per unit of milk production.

Now, pricing varies considerably by region and purchase volume—you probably know this already. Industry data suggests Bovaer costs range from $0.30 to $0.50 per cow daily, while Rumensin (that’s monensin from Elanco) typically runs $0.13 to $0.15 per cow per day. Rumensin provides modest emission reductions, but it also delivers about a 3% improvement in feed efficiency, according to Elanco’s published data. That’s nothing to sneeze at when you’re looking at overall dairy milk check revenue.

Precision nutrition approaches, particularly those low-protein, amino acid-balanced rations, offer another pathway without requiring infrastructure investment. These strategies reduce nitrogen excretion and associated nitrous oxide emissions while potentially improving your feed cost efficiency. Ajinomoto’s AjiPro-L protocol, which Athian approved in April, exemplifies this approach. University of Wisconsin Extension trials indicate potential for both ration cost savings and carbon credit generation, though—as you’d expect—results vary by operation.

Anaerobic digester systems continue to provide opportunities for larger operations. You can stack RNG revenue, RIN credits, nutrient products, and now carbon insets. But let’s be realistic about the economics here—USDA NRCS data and Cornell’s agricultural economics research show you need at least $1,800 per cow in capital investment. Even with RCPP cost-share programs covering 50-75% of installation costs, that’s a serious commitment that really only pencils out at significant scale.

What I’m particularly interested in are these whole-farm carbon intensity protocols. Rather than requiring specific expensive interventions, they measure your overall emissions per unit of milk production. California’s CDFA has been developing this methodology, while the Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy has been creating parallel frameworks. If you’re already efficient—getting more milk from fewer cows with less waste through better genetics and reproduction—you should theoretically qualify even without fancy additives. And looking ahead, emerging technologies such as seaweed-based additives and genetic selection for lower-emission cows could further expand options, though they are still in development.

Economic Realities Across Different Scales

Here’s where things get really interesting for dairy farm profitability, and the implications vary dramatically by operation size. Let me share what I’ve learned from producers at different scales, including those Southeast operations dealing with heat stress and different housing systems.

A Wisconsin producer I know with 450 cows spent three months getting all his documentation together, and when the first payment came through, it was $4,200. As he told me, “It’s certainly welcome income, but when you consider the time investment and upfront costs, it doesn’t fundamentally change our operation.”

For a typical 500-cow dairy in Wisconsin or Pennsylvania—and I’ve run these numbers with several folks—participating in carbon credits for dairy farms looks something like this: Initial investment in feed additives runs $25,000 to $30,000 annually, assuming you’re using a combination of products. Data system upgrades, if you need them, add $2,000 to $5,000. Nutritionist consultation and protocol documentation typically cost another $1,000 to $2,000.

So you’re looking at a total upfront investment of $28,000 to $37,000.

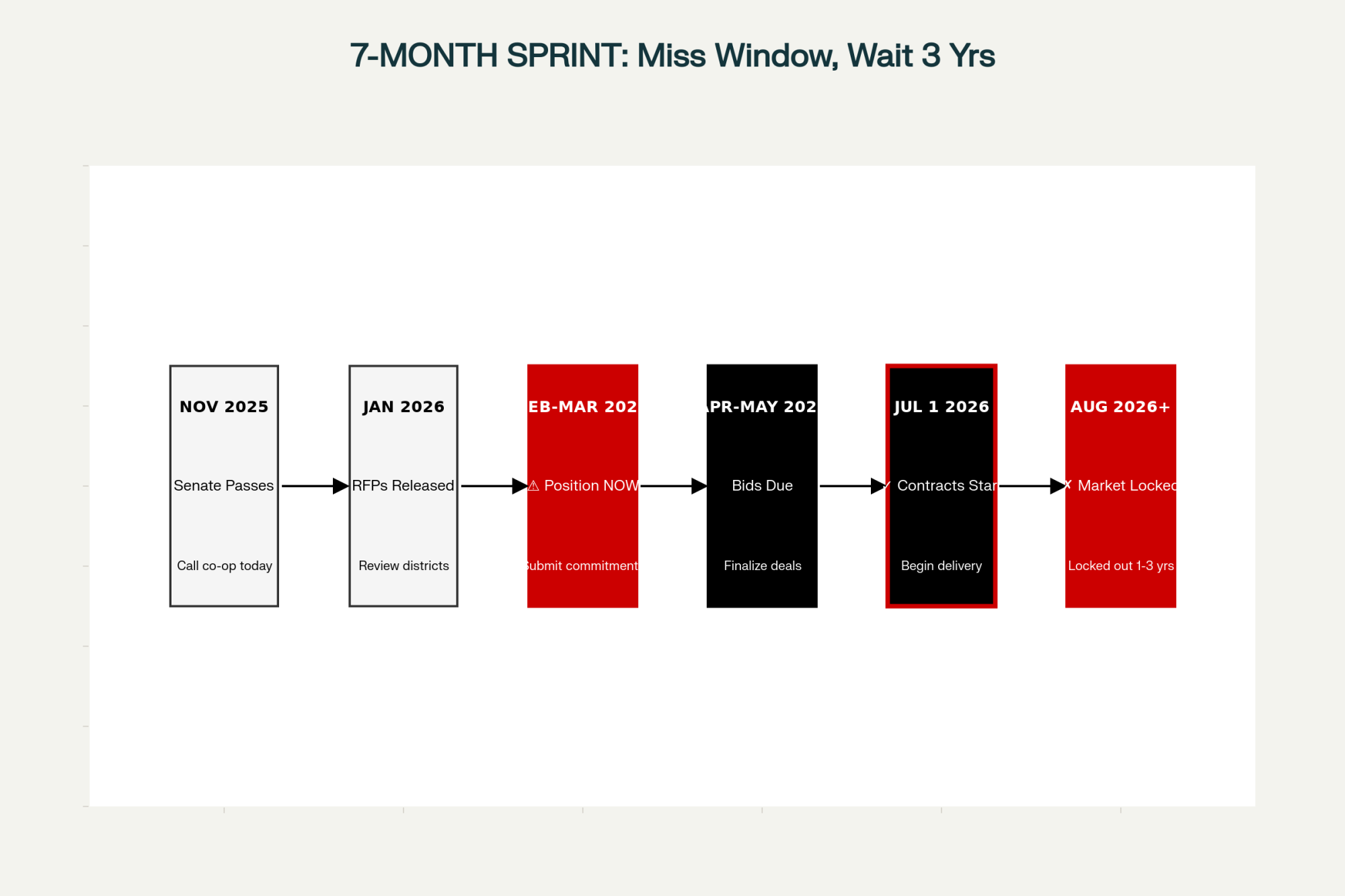

And here’s the kicker—you pay these costs immediately, but receive carbon credit payments after 6 to 12 months of verification, per Athian’s current terms. That means you need that cash sitting available, not borrowed.

Current carbon pricing at $60 per ton represents a historical high—the Ecosystem Marketplace reports voluntary carbon markets averaged just $6.37 per ton in 2024. At these prices, a 500-cow operation might generate $5,000 to $8,000 in annual carbon revenue. Combined with potential feed efficiency gains of $15,000 to $20,000, net benefits could reach $20,000 to $28,000 annually. But that’s assuming stable carbon prices, smooth verification, and favorable baseline calculations…

The economics shift significantly at larger scales. An Idaho dairy manager I spoke with, who’s running 3,200 cows, explained: “We’re generating about $47 per cow from carbon credits, plus the feed efficiency improvements. At our scale, that translates to over $150,000 annually—meaningful revenue that justifies the administrative investment.”

This reveals something important for dairy milk check revenue: while per-cow returns are similar ($40-56 for smaller operations versus $43-57 for larger ones), the absolute dollar amounts make participation worthwhile for larger operations while remaining marginal for smaller ones.

Operations That Should Consider Alternatives

Based on extensive discussions with producers and financial advisors from Michigan to Arizona, certain operations face structural barriers that make successful participation in current dairy carbon credit programs challenging for overall dairy farm profitability.

If your working capital ratio is below 1.25, you don’t have the financial flexibility to manage that 6 to 12-month payment delay. The Farm Financial Standards Council identifies this as a critical threshold for operational stability, and I’ve seen this play out firsthand. One producer near Viroqua, Wisconsin, with 380 cows, carefully analyzed his situation. He told me, “Borrowing to cover upfront costs at 8% interest would essentially eliminate any carbon revenue benefit. The mathematics simply didn’t support participation.”

If you’re still using paper-based or basic spreadsheet record-keeping, the documentation burden will probably eat you alive. These carbon programs for dairy farms require integrating feed invoices, ration records, and milk production data in formats that support third-party verification. It’s not impossible with manual systems, but honestly, the administrative burden often becomes prohibitive.

“The transition from paper to carbon credits simply doesn’t occur—it’s from digital systems to carbon credits.”

Pasture-based operations encounter technical limitations with current protocols. Both Bovaer and Rumensin require consistent daily dosing through total mixed rations. DSM’s product development pipeline includes slow-release bolus systems for grazing operations, but they aren’t yet commercially available. These producers may find better opportunities in whole-farm intensity protocols that recognize the inherent efficiency of well-managed grazing systems. This is particularly relevant for Southeast producers, where year-round grazing is more common.

And if you’re approaching retirement within 5 to 7 years, you should carefully evaluate participation. These programs typically achieve optimal returns over 10 to 15-year horizons, allowing carbon revenues to compound and infrastructure investments to fully amortize.

Industry Structure Implications

Something we need to consider thoughtfully is how these programs might affect industry structure and long-term patterns of dairy farm profitability. Large-scale operations in Texas, Idaho, and California that implement comprehensive carbon programs might generate $200,000 or more annually. That creates meaningful cash flow advantages and balance sheet improvements that can influence expansion decisions and market dynamics.

Meanwhile, a 400-cow operation might generate $3,000 in carbon credits—barely covering administrative costs. When milk prices cycle from $20 to $16 per hundredweight, as they periodically do, operations with substantial carbon revenue cushions have clear advantages in weathering these downturns.

Current USDA Census of Agriculture data show we’re losing 2,100 to 2,800 dairy farms annually, with exits concentrated in the 150- to 1,500-cow range. While dairy carbon credit programs don’t cause this consolidation, they may influence its pace by providing additional advantages to operations already benefiting from economies of scale.

This raises important questions about program design and accessibility that we as an industry continue to grapple with.

Common Success Factors

Producers successfully participating in these programs—whether they’re in the Northeast, Midwest, or Western regions—share several characteristics worth noting for those seeking to enhance dairy milk check revenue.

Cooperative participation proves crucial. Working through established programs at DFA, Land O’Lakes, or similar organizations significantly reduces administrative complexity. The co-ops handle documentation aggregation, facilitate buyer connections, and provide technical support that individual producers would struggle to replicate on their own.

Financial strength matters—a lot. Successful participants typically maintain working capital ratios above 1.5, giving them the flexibility to manage payment timing without incurring debt. As one Wisconsin producer with 1,100 cows near Fond du Lac observed, “If carbon payments are necessary for cash flow, the operation probably isn’t ready for program participation.”

These successful producers view carbon credits as complementary to operational improvements rather than primary drivers of dairy farm profitability. A Pennsylvania dairyman with 750 cows explained their perspective: “We were evaluating Rumensin for efficiency gains regardless. The carbon credits transformed a good decision into an obvious one.”

And digital infrastructure proves essential. Not necessarily sophisticated systems, but at least DHIA participation, computerized ration management, and organized record-keeping. The transition from paper to carbon credits simply doesn’t occur—it’s from digital systems to carbon credits.

Verification Processes and Practical Considerations

Understanding verification helps set realistic expectations for dairy carbon credit programs. Programs begin by establishing baseline emissions using models with acknowledged uncertainty ranges of 15-25%, in accordance with IPCC methodology and UC Davis CLEAR Center analysis. Your baseline could vary substantially in either direction—something to keep in mind.

Implementation requires comprehensive documentation—feed invoices, ration formulations, production records, and health events. Verification bodies, including SustainCERT and other ISO 14064-accredited auditors working with Athian, review this documentation through varying combinations of remote review and farm visits.

One Wisconsin producer with 650 cows near Bloomer experienced the complexity of verification firsthand. Initial approval was questioned 6 months later when butterfat levels changed, potentially indicating variation in the feed additive. Three additional months of documentation were required to verify consistent feeding practices. The final payment arrived 11 months late, rather than the anticipated 6.

Credit registration on Athian’s blockchain ledger prevents double-selling within their system. But as the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy noted in their recent analysis of insetting risks, enforcement mechanisms across different platforms remain underdeveloped. Something to be aware of.

Looking Ahead: Realistic Expectations for 2030

If current trajectories continue, what might we reasonably expect for dairy farm profitability by decade’s end?

Industry-wide emissions intensity could decrease 20 to 30% through combined adoption of feed additives, ration optimization, and efficiency improvements. California Air Resources Board data already show a 20% reduction in methane intensity from early adopter programs, suggesting this target is achievable.

Mid-size farm participation could expand through cooperative-led programs that aggregate verification costs and streamline administration. Replicating DFA’s model across major cooperatives could make participation as routine as DHIA testing for appropriately positioned operations.

Carbon price stabilization through corporate commitments seems plausible. Companies might guarantee minimum prices of $40 to $50 per ton for verified reductions from their supply chains, providing investment confidence for participating producers.

Policy mechanisms could amplify market-based approaches. Implementation of the 45Z tax credit under the Inflation Reduction Act could establish price floors. State programs, like California’s $25 million methane-reduction initiative through its Climate Smart Agriculture program, demonstrate potential for complementary support.

Realistically, I anticipate 2,000 to 3,000 larger farms generating $150 to $300 million in cumulative payments by 2030—meaningful for those operations but unlikely to transform industry-wide economics or substantially alter consolidation patterns affecting dairy milk check revenue across all farm sizes.

A Practical Decision Framework

For producers considering participation to enhance dairy farm profitability, here’s a systematic evaluation approach based on actual participant experiences:

Step 1: Assess your working capital ratio. Below 1.25 indicates you need operational stabilization before adding program complexity.

Step 2: Calculate your true break-even costs, including all expenses. If you’re exceeding $20 per hundredweight in current markets, carbon credits won’t address fundamental profitability challenges.

Step 3: Evaluate available cash reserves. Can you deploy $25,000 to $35,000 for 6 to 12 months without borrowing? Interest costs often eliminate carbon revenue benefits.

Step 4: Engage your cooperative. Established programs with clear protocols and payment histories indicate readiness. “Exploring options” suggests patience might be warranted.

Step 5: Review your documentation capabilities. Digital ration management, DHIA participation, and nutritionist relationships all contribute to readiness.

Step 6: Consider your time horizon. Ten-plus year operational plans align well with program economics. Five-year exit strategies likely don’t.

This framework probably excludes 70 to 80% of U.S. dairy farms, which itself reveals important characteristics about current market design and its impact on dairy farm profitability.

Broader Industry Implications

The emergence of functional dairy carbon markets represents genuine progress. It demonstrates corporate willingness to invest in verified emissions reductions, validates market mechanisms for environmental progress, and rewards efficiency improvements that many of us pursue regardless.

Yet it also illuminates the limitations of the agricultural market. These mechanisms naturally favor scale, sophistication, and capital access—characteristics already driving industry evolution. Programs generating $150,000 annually for large operations while offering $3,000 to smaller farms reflect market dynamics rather than program design flaws.

This isn’t attributable to any particular organization or conspiracy. It’s simply how markets function when transaction costs are substantial and economies of scale are significant. The relevant question isn’t fairness but rather our collective comfort with carbon markets as another factor influencing industry structure and dairy milk check revenue distribution.

My assessment? These represent useful tools rather than transformative solutions for dairy farm profitability. Well-capitalized operations already pursuing efficiency improvements will find carbon revenues provide a welcome acceleration. Marginal operations won’t find salvation here. For the broader industry, it’s another advantage accruing to scale in an already scale-advantaged system.

Evaluate these opportunities based on your specific situation. But maintain realistic expectations about carbon credits as supplemental revenue rather than foundational income, especially given agriculture’s historical pattern of commodity price volatility.

Athian’s $18 million in payments is real. The practices deliver results. The verification systems function. But whether this matters for your particular operation depends entirely on where you sit within dairy’s increasingly differentiated structure. And that’s the conversation we need to continue having—not just whether carbon markets work, but how they work within our evolving industry landscape and their real impact on dairy farm profitability.

Editor’s Note: Producer experiences shared in this article are based on interviews conducted in November 2025.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The $18M reality: Carbon credits paid dairy farmers real money in 2024, but large operations (3,000+ cows) capture $150,000 annually while family farms (500 cows) get just $3,000-8,000 for identical practices

- Why scale always wins: Per-cow profits are virtually the same at $40-56, but you need 2,000+ cows to cover the $30,000 upfront investment and 6-12 month cash flow gap

- Your qualification checklist: Must have a working capital ratio >1.25, digital record systems already running, and participate through established co-op programs—miss any one and you should pass

- Bottom line decision: Carbon credits work for well-capitalized operations planning 10+ year horizons, but won’t save struggling farms—they amplify existing advantages rather than leveling playing fields

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Generate $15,000+ Annual Carbon Revenue: The Dairy Producer’s Guide to Getting Paid for Going Green – Reveals specific strategies to stack USDA EQIP payments with private carbon credits, demonstrating how to unlock $14,000–$25,000 in net revenue for 1,000-cow herds while avoiding the common paperwork traps that derail participation.

- Decide or Decline: 2025 and the Future of Mid-Size Dairies – Delivers a brutal but necessary financial roadmap for the squeezed 700-1,200 cow sector, explaining why “holding steady” drains 6–8% of equity annually and outlining three specific business models that ensure survival in a consolidated market.

- The Methane Misdirection: Why The Industry’s Obsession with Feed Additives Is Costing You Money While Genetics Offers the Real Solution – Challenges the current focus on expensive daily feed additives by presenting data on genetic selection for methane efficiency, offering a permanent, cumulative reduction strategy that doesn’t require monthly checks to additive suppliers.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.