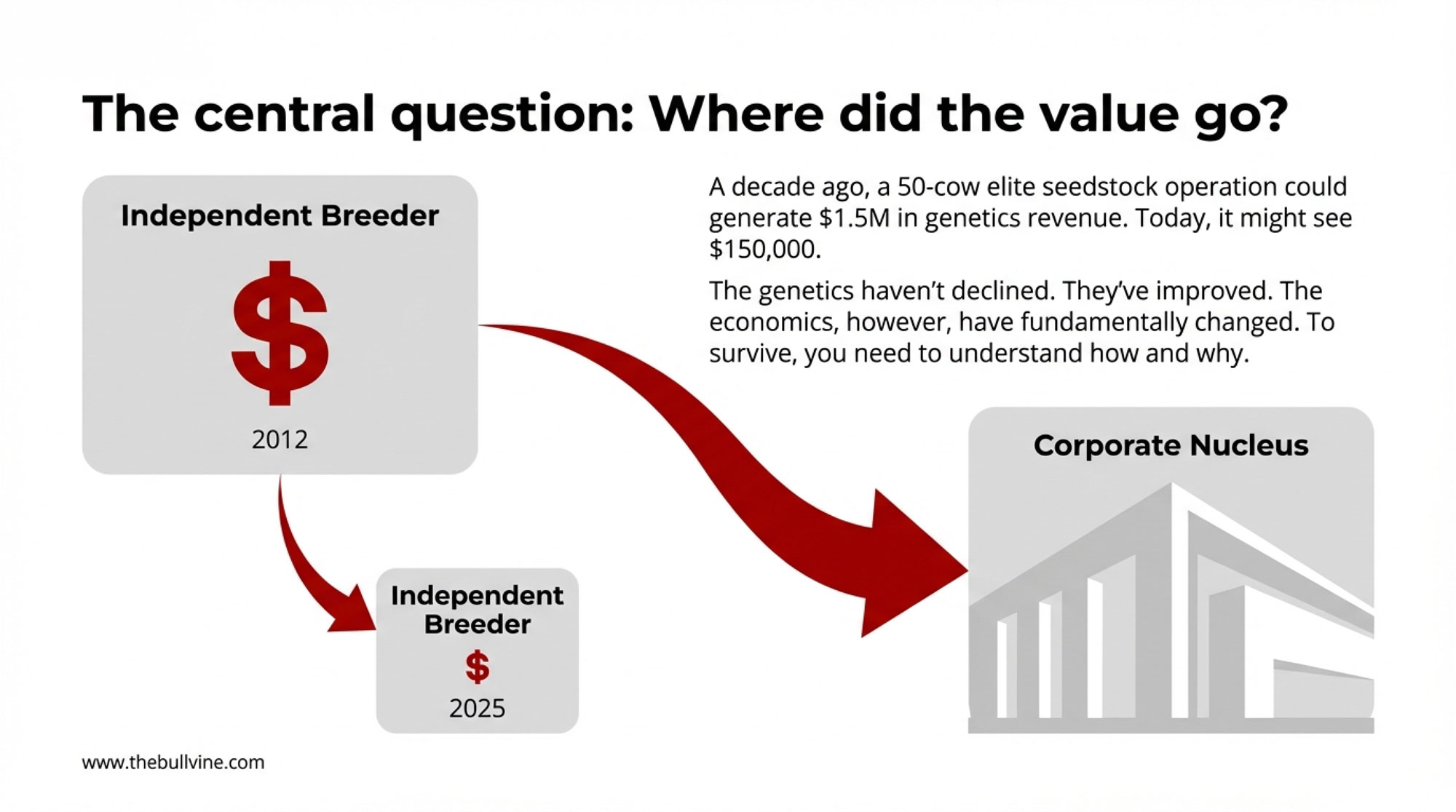

The dairy genetics business that built family operations for generations? It’s been restructured. $1.5M down to $150K. But some breeders are finding new paths. Here’s what they figured out.

I was talking with a third-generation Holstein breeder from central Wisconsin not long ago, and what he shared really stayed with me. Back in 2012, his operation moved about $900,000 in genetics—semen, embryos, and a handful of elite females. Last year? Around $85,000. Same dedication, arguably better cows, and he’s generating roughly a tenth of what he used to.

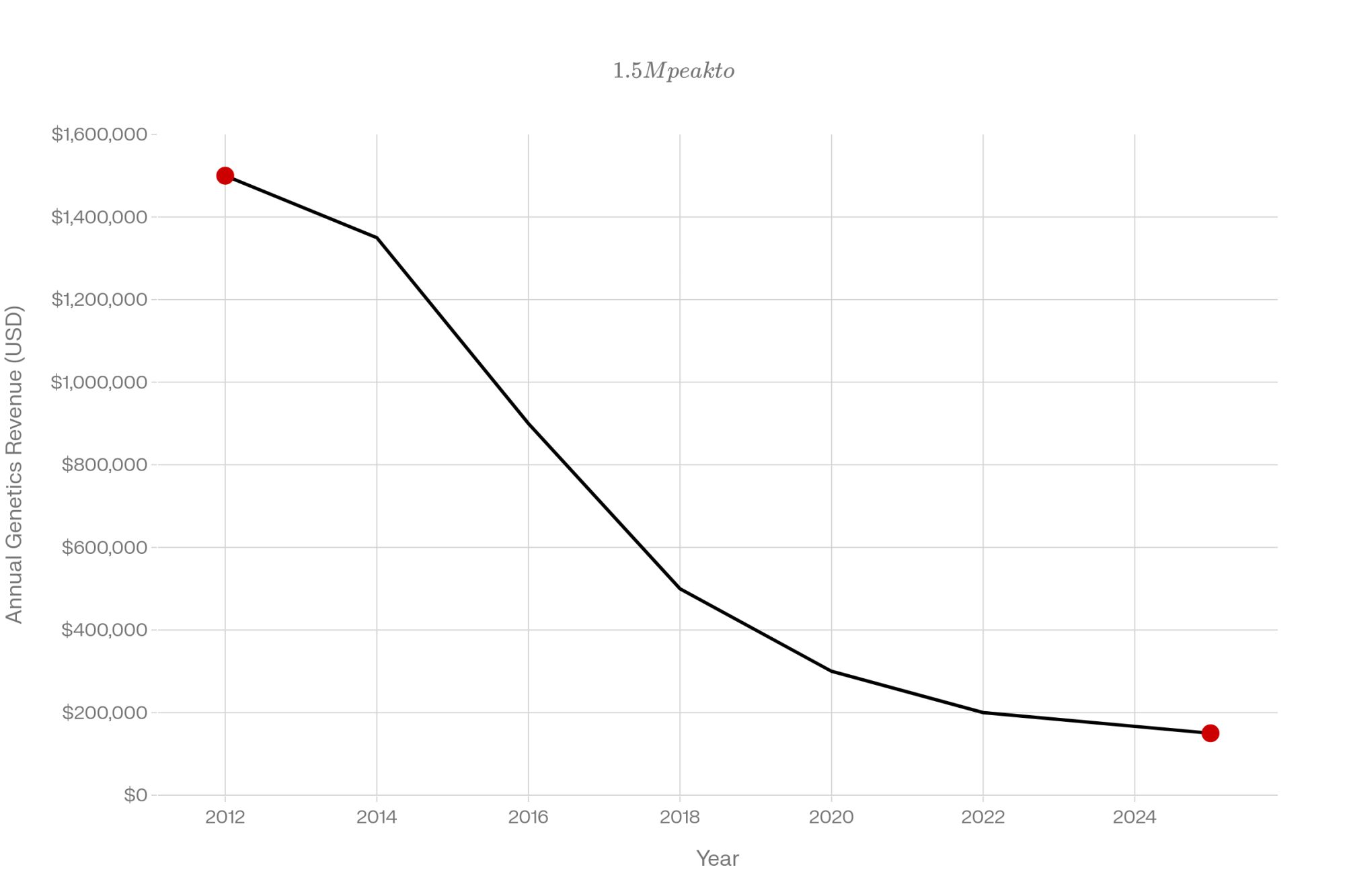

His story isn’t unusual. Based on conversations across the industry and market data, a well-managed seedstock operation with 50 elite cows could realistically generate over $1.5 million annually from genetics sales. Today, that same operation might see $100,000 to $200,000. The genetics haven’t declined. If anything, they’ve improved considerably. But the economics have shifted in ways that caught many breeding families by surprise. (Read more: Master Breeder Killed in Triple Homicide and Who Killed The Market For Good Dairy Cattle?)

What’s worth understanding here isn’t simply that the industry changed—it always does. The more useful question is where the value actually went, and what realistic options remain for producers navigating this new landscape.

AT A GLANCE: Key Numbers Shaping Dairy Genetics

- $170 million — What URUS paid for Trans Ova Genetics back in 2022

- 9.99% — Average inbreeding level for Canadian Holstein heifers born in 2024

- 400% — Growth in U.S. grass-fed organic dairy farmers since 2016

- $8.5 billion — U.S. organic dairy and egg sales in 2024, up 7.7% from the year before

- 18% — Portion of Holstein PTA changes now tied to inbreeding adjustments

- $14.78 billion — Where the global animal genetics market is headed by 2032

How the Breeding Model Changed

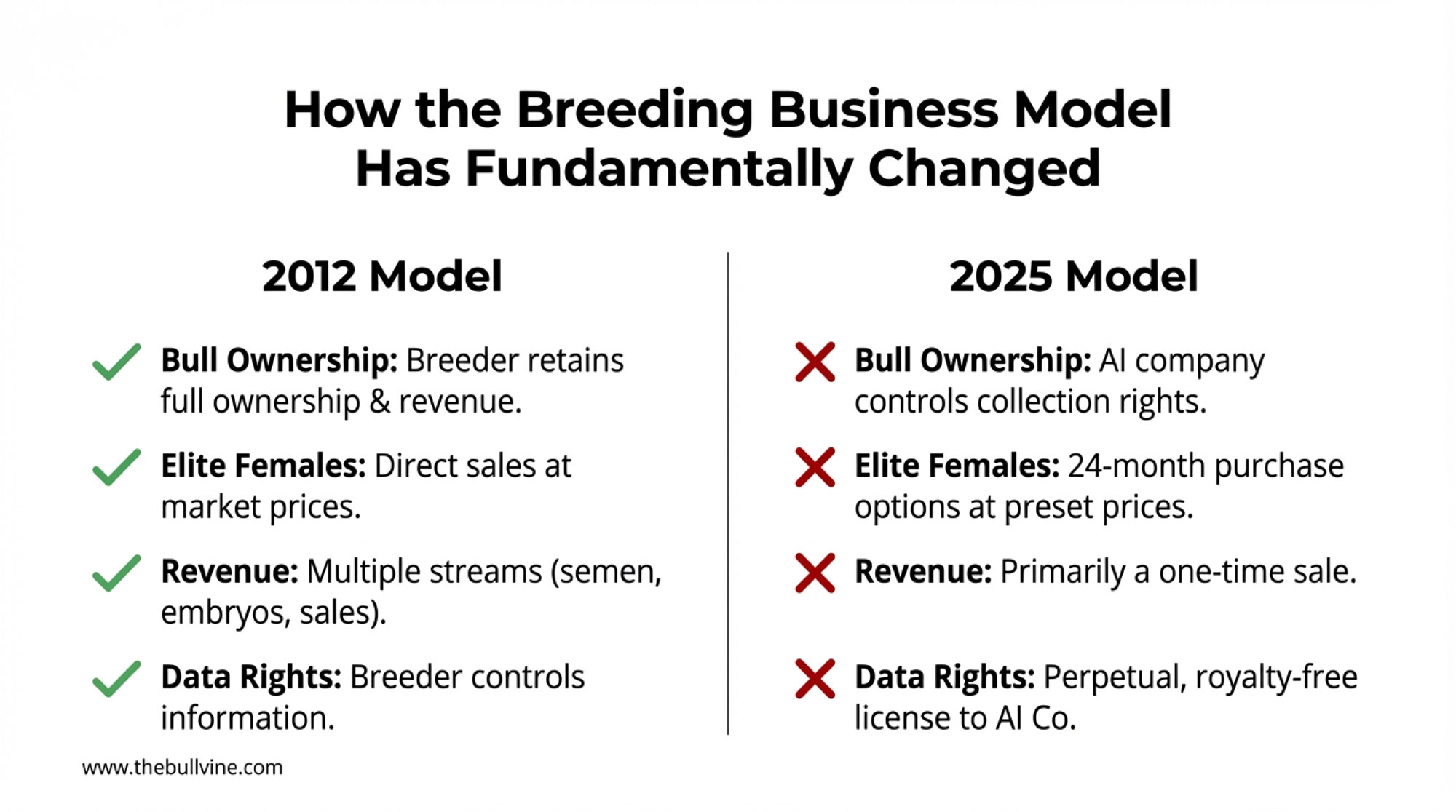

| Dimension | 2012 Model | 2025 Model |

| Bull Ownership | Breeder retains full ownership; collects and markets semen independently | An AI company typically controls collection rights; the breeder may own the animal, but not the revenue stream |

| Elite Female Sales | Direct sales to other breeders at market-negotiated prices; ongoing relationships | 24-month purchase options at preset prices; females enter corporate nucleus herds |

| Revenue Streams | Semen royalties, embryo sales, show winnings, private treaty females, consulting | Primarily one-time sale; limited ongoing participation in genetic value |

| Data Rights | Breeder controls genetic information; shares selectively | Perpetual, royalty-free licenses to AI companies through testing agreements |

| Market Access | Direct relationships with commercial farms and other breeders | Corporate distribution channels; limited independent marketing |

| Capital Requirements | Moderate investment in facilities and marketing | $2-5 million+ to compete at the elite level with JIVET infrastructure |

The Technology That Reshaped Everything

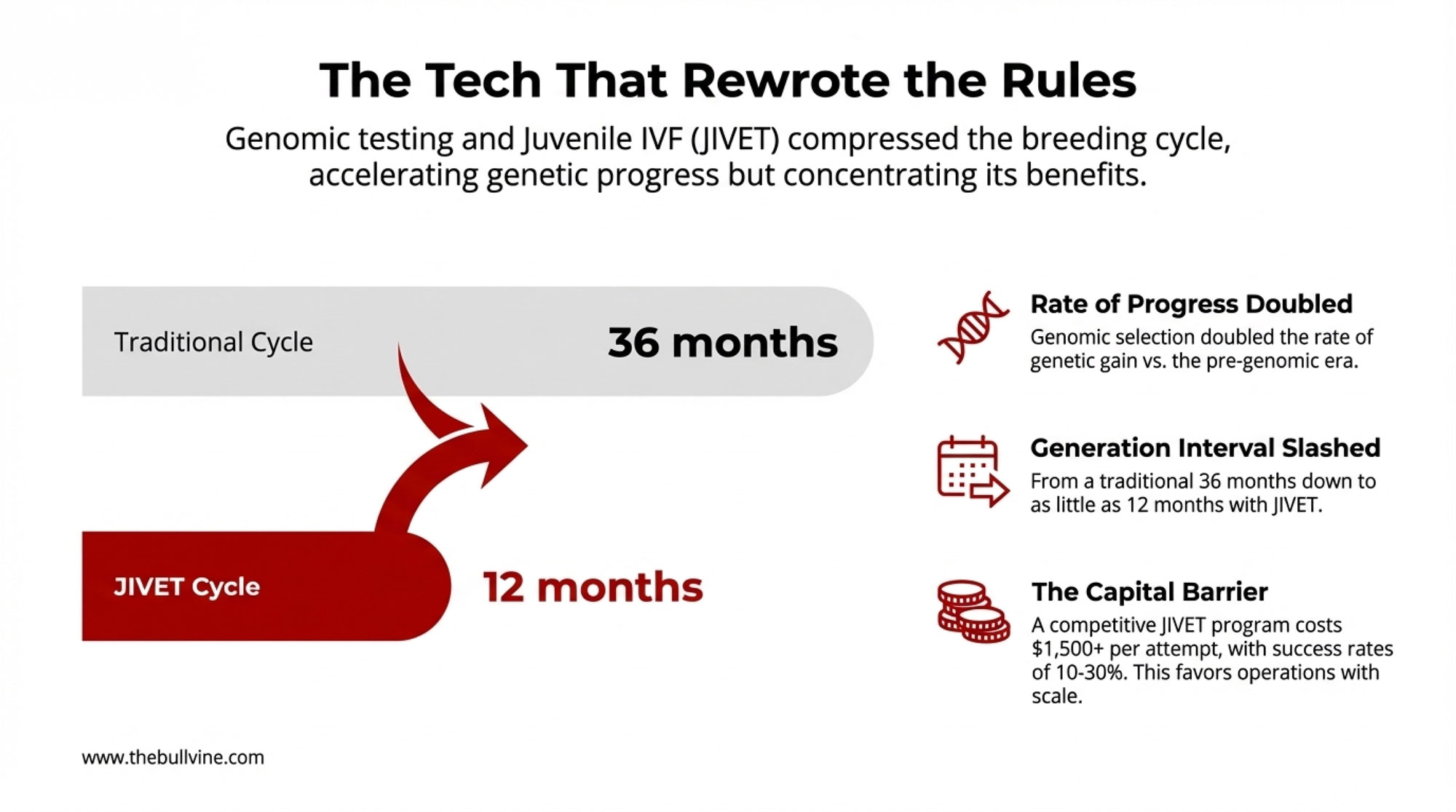

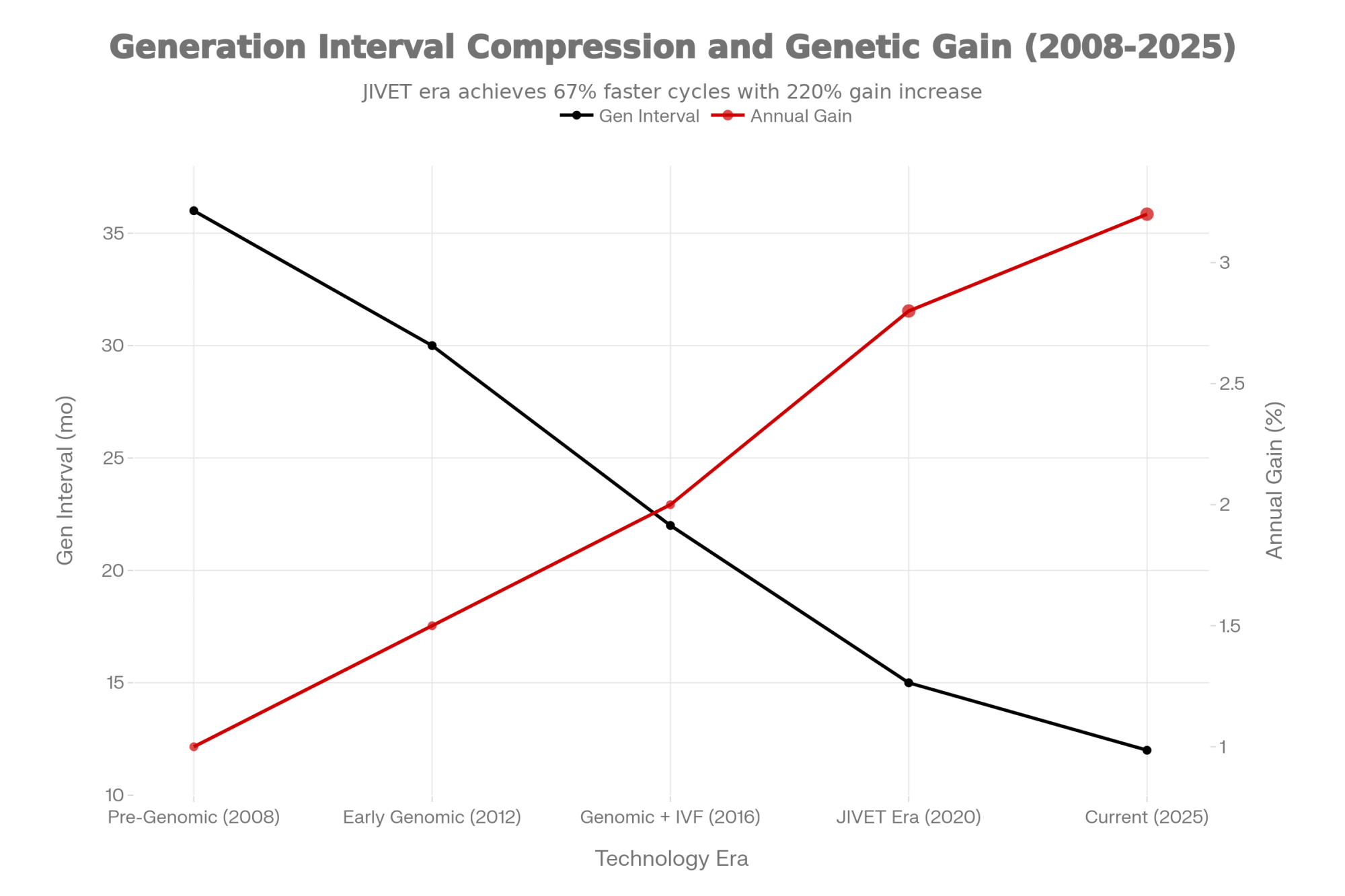

The transformation really began with genomic testing around 2009, though the full impact emerged when reproductive technologies matured enough to compress generation intervals in ways few anticipated.

Here’s the development that matters most: Juvenile IVF—sometimes called JIVET—now allows oocyte recovery from heifer calves as young as two to three months old. Consider what that means. Traditional breeding required waiting until an animal reached puberty, typically 10 to 14 months, before any embryo work could begin. That single advancement compressed generation intervals from roughly 36 months down to around 12 months for operations with the capital and infrastructure to implement it.

The Council on Dairy Cattle Breeding has documented how genomic selection approximately doubled the rate of genetic progress compared to the pre-genomic era—a finding confirmed by research published in Frontiers in Genetics and validated through years of industry data. Combine that with shortened generation intervals through juvenile IVF, and you’re looking at genetic advancement rates that simply weren’t achievable under the previous model.

Dr. Paul VanRaden—the research geneticist with USDA’s Animal Genomics and Improvement Laboratory—noted in CDCB documentation that the April 2025 genetic base change reflects the improvements in genetics and management accumulated over the previous five years. Those gains are real, and commercial farmers are genuinely benefiting from better cattle arriving faster than ever before.

But here’s the catch: the technology that accelerated genetic progress also concentrated its benefits. Running a competitive juvenile IVF program generally costs $1,500 or more per attempt, with success rates showing considerable variability—often ranging from 10 to 30 percent for transferable embryos, depending on stimulation protocols and individual donor response. At scale, those economics work well. For individual operations without that scale, each attempt carries meaningful risk.

| Technology Era | Generation Interval (months) | Annual Genetic Gain (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Genomic (2008) | 36 | 1.0 |

| Early Genomic (2012) | 30 | 1.5 |

| Genomic + IVF (2016) | 22 | 2.0 |

| JIVET Era (2020) | 15 | 2.8 |

| Current (2025) | 12 | 3.2 |

Following the Corporate Realignment

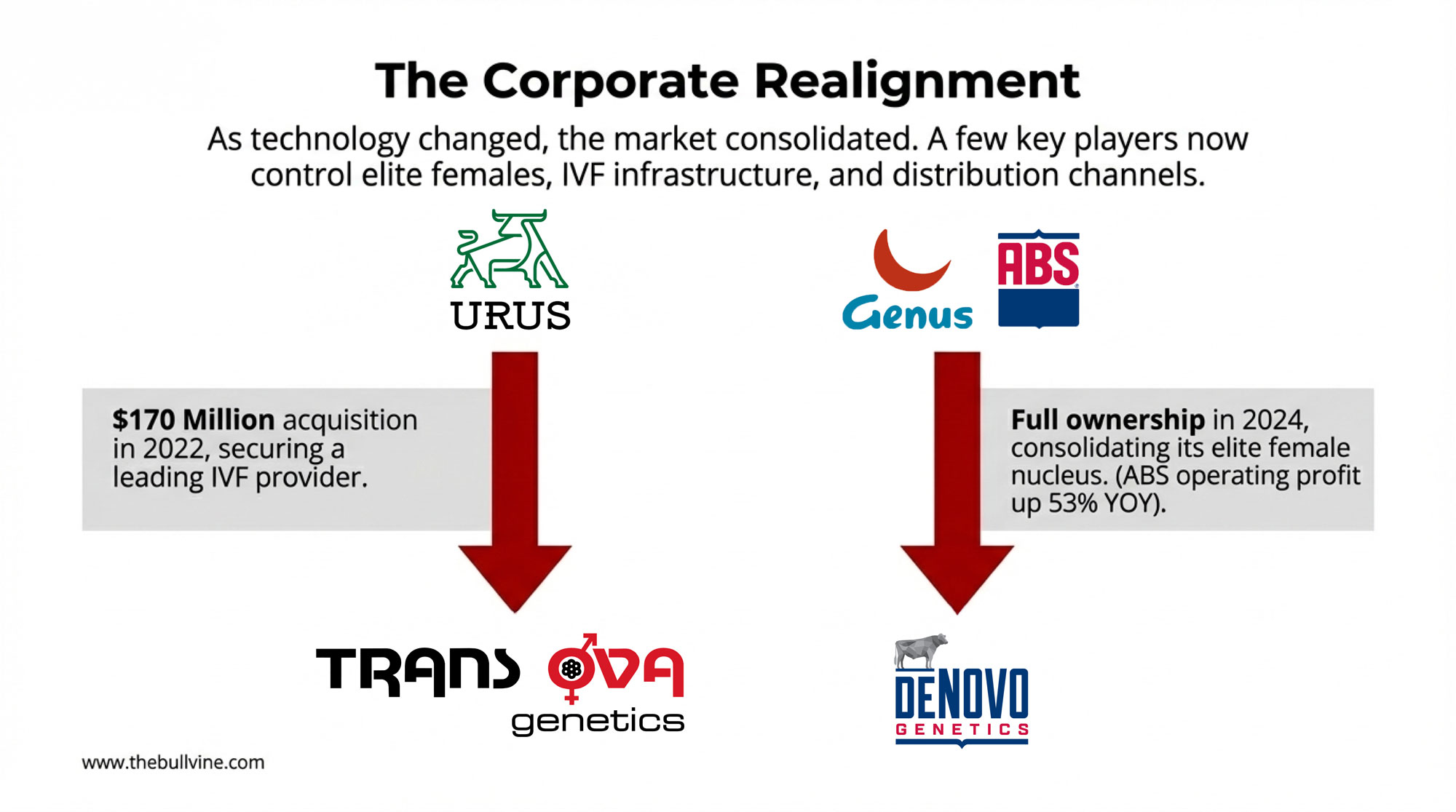

The past seven years have brought consolidation that has significantly restructured market access. For those who haven’t been closely tracking corporate developments, here’s the landscape.

In 2018, URUS formed through the merger of Koepon Holding (Alta Genetics’ parent company) and Cooperative Resources International, which owned GENEX. That created the second-largest global cattle genetics company. Four years later, URUS acquired Trans Ova Genetics—North America’s leading embryo transfer and IVF services provider—for $170 million in upfront cash plus a potential $10 million earnout. Those figures come directly from the SEC filings for the deal, which closed in August 2022.

David Faber, the veterinarian who serves as Trans Ova’s CEO and President, explained at the time that the company looked forward to working with URUS to add strategic resources that would further enhance their reproductive technology capabilities.

Meanwhile, ABS Global—owned by UK-based Genus PLC—moved to full ownership of De Novo Genetics in September 2024, consolidating control over its elite female nucleus. Genus PLC’s 2025 annual report showed the ABS division with adjusted operating profit up 53 percent year-over-year. That’s substantial growth in a mature industry segment.

What does this mean practically? When a single company controls elite females, IVF infrastructure, semen distribution, and genomic evaluation tools, the traditional breeder’s role in that value chain changes considerably. That’s neither inherently good nor bad—it’s just different from how things worked before, and it requires different strategies.

The Contract Terms Worth Understanding

| Contract Element | Breeder Retains (2012 Model) | Breeder Retains (2025 Model) | Value Transfer to Corporate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bull Semen Rights | 100% | 0% | Complete |

| Elite Female Purchase Options | 100% | 0% | Complete |

| Genomic Data Ownership | 100% | 0% | Complete |

| Male Offspring Sales | 100% | 15-25% | Substantial |

| Ongoing Royalties | 100% | 0-5% | Near-Complete |

Modern elite genetics programs typically come with contractual arrangements that differ from how breeding partnerships worked a generation ago. While terms vary by program and continue evolving, here’s what many current structures look like.

Under programs in the past, breeders using elite genetics generally sign contracts that transfer the rights to collect semen to the AI company. The breeder may own the bull, but the company controls—and captures revenue from—semen production and sales. Male offspring from elite matings are typically directed to beef markets or sold to the AI company at predetermined prices. Breeders usually cannot retain bulls for independent semen collection or sell them to competing operations.

For elite females, purchase options often extend 24 months, during which the genetics company holds first right of refusal at preset prices—frequently in the $40,000 to $100,000 range for top-ranked animals based on current market activity. After that transaction, the cow typically enters a corporate nucleus herd, and the original breeder captures no further value from her offspring.

Genomic testing agreements generally grant AI companies perpetual, royalty-free licenses to use all submitted genetic data. That information—aggregated across thousands of herds—becomes the proprietary database that powers genetic indices and breeding recommendations.

These arrangements are disclosed in publicly available terms and conditions. Understanding them before committing helps breeders make informed decisions about whether specific programs align with their business objectives.

BEFORE YOU SIGN: Questions for Elite Genetics Programs

- Who controls semen collection rights if I raise a high-genomic bull?

- What are the purchase option terms and timeline for elite females?

- How is my genomic data used, and do I retain any ownership rights?

- What happens to male offspring from elite matings?

- Are there restrictions on selling genetics to competing programs?

Want more detail? Download our expanded Contract Negotiation Guide at thebullvine.com/resources—including term-by-term analysis, red flags to watch for, and questions your attorney should ask before you commit.

The Inbreeding Question

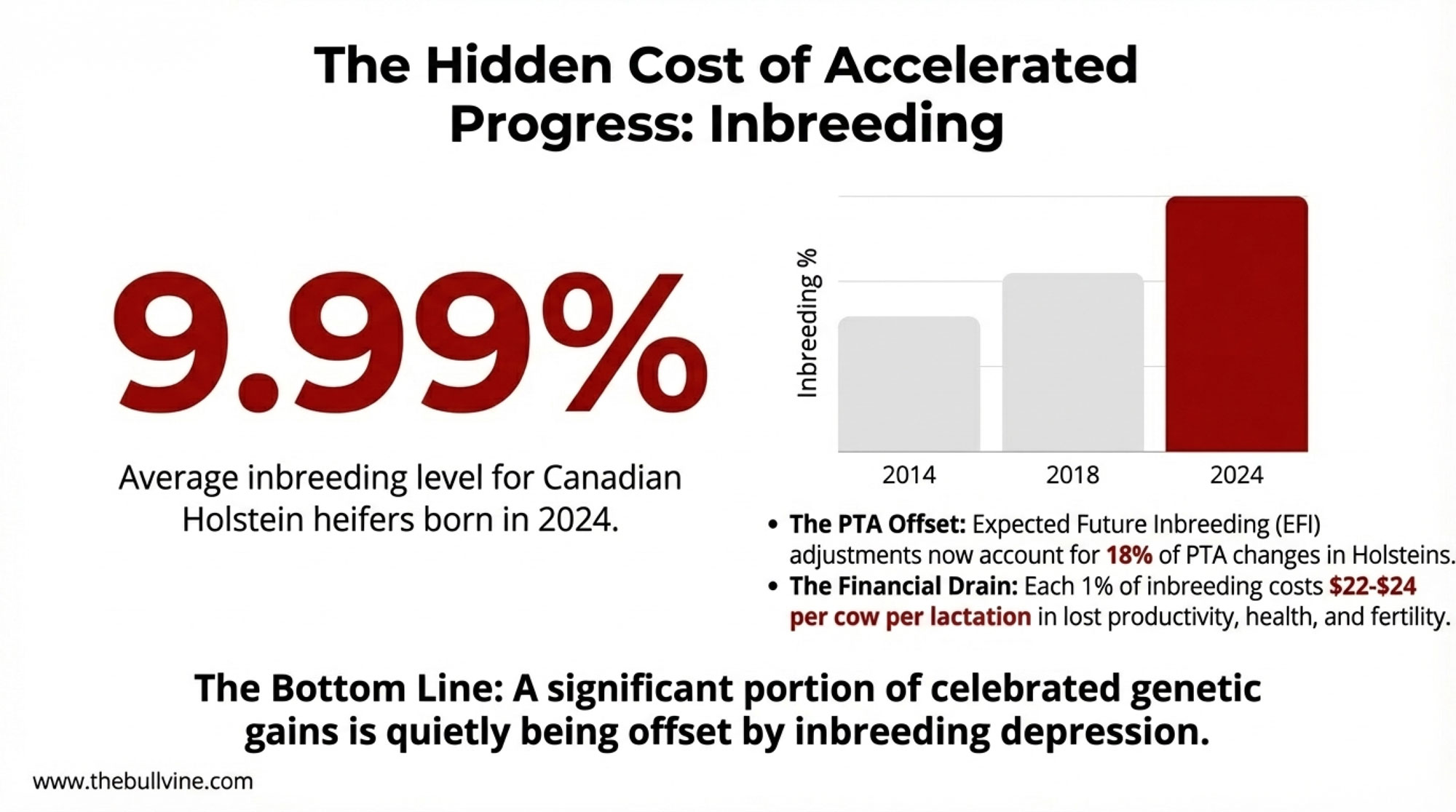

One development that deserves attention alongside consolidation is the acceleration of inbreeding within major dairy breeds. It’s a pattern that accompanies rapid genetic progress under concentrated selection, and it warrants thoughtful monitoring.

Lactanet’s August 2025 inbreeding update reports that average inbreeding levels for Canadian Holstein heifers born in 2024 reached 9.99 percent, with Jerseys at 7.56 percent. U.S. figures from CDCB show similar patterns, with genomic inbreeding in Holsteins running notably higher than a decade ago.

The April 2025 CDCB genetic base change revealed something worth noting: Expected Future Inbreeding adjustments now account for roughly 18 percent of PTA changes in Holsteins. As the National Association of Animal Breeders explained in their base change documentation, CDCB introduced additional changes to their genetic evaluations that weren’t included in earlier estimates, including updated EFI calculations.

What this means, practically, is that a portion of apparent genetic progress is offset by inbreeding depression. Industry estimates, including those from the Holstein Association USA, suggest each percentage point of inbreeding costs approximately $22 to $24 per cow per lactation in reduced productivity, health, and fertility.

| Breed | Current Inbreeding % | Cost per 1% ($/cow/lactation) | Total Annual Cost per Cow ($) | Warning Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holstein | 9.99% | $23 | $230 | High |

| Jersey | 7.56% | $22 | $166 | Elevated |

| Brown Swiss | 6.80% | $23 | $156 | Moderate |

| Ayrshire | 5.20% | $22 | $114 | Acceptable |

Is this tradeoff problematic? Not necessarily. Faster genetic gain may still outweigh inbreeding costs for most operations, particularly those using crossbreeding strategies or careful mating programs. But the calculation isn’t as straightforward as index numbers might suggest—something worth considering for breeders making long-term decisions about bloodline diversity.

Real-World Adaptations

I’ve been watching how different operations respond to these shifts, and the approaches vary considerably based on scale, goals, and regional markets. What’s encouraging is that several breeders are finding genuine opportunities in segments the major programs don’t prioritize.

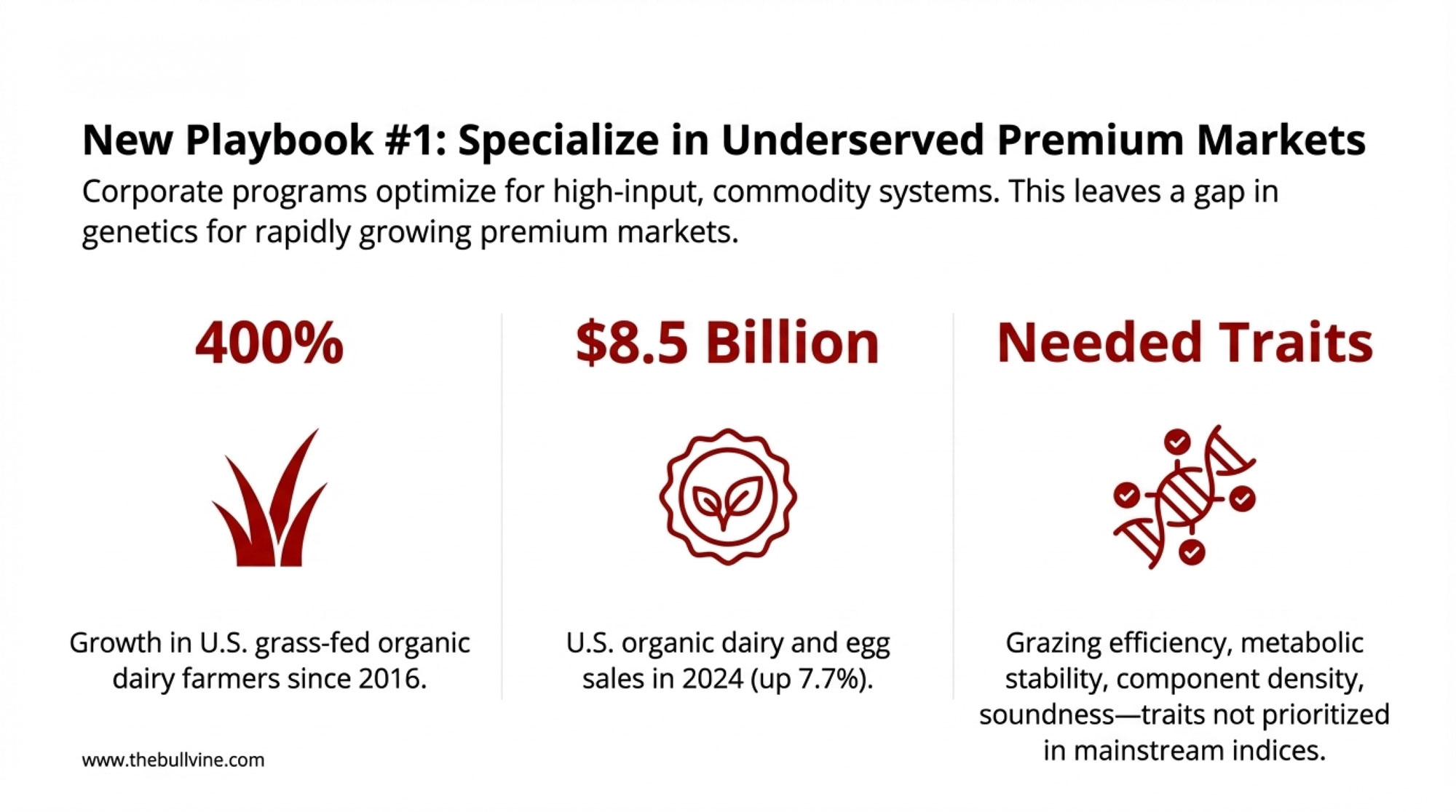

The grass-fed and organic dairy sector offers a compelling example. According to Market Growth Reports, the global grass-fed milk market reached approximately $63.7 billion in 2024, with projected compound annual growth exceeding 20 percent through 2033. North America represents the largest share of that consumption.

The Organic Trade Association reported that organic dairy and egg sales rose 7.7 percent to $8.5 billion in 2024, with organic yogurt growing 10.5 percent—what they called the second highest growth rate in the category in more than 15 years.

Why does this matter for genetics? Corporate programs optimize primarily for high-producing operations using concentrate-based feeding systems. Grass-fed operations need different trait combinations: grazing efficiency and forage intake capacity; metabolic stability across seasonal pasture variations; component percentages (butterfat and protein performance on grass-only diets); fertility and calving ease with minimal intervention; and structural soundness for pasture locomotion across multiple lactations.

Those traits don’t receive priority in mainstream selection indices. Which creates a genuine opportunity for breeders willing to specialize.

A University of Vermont survey led by researchers Heather Darby and Sara Zeigler found that U.S. grass-fed organic dairy farmers have expanded by over 400 percent since 2016. The Northeast Organic Dairy Producers Alliance reports continued movement toward grass-fed certification, with companies like Maple Hill actively signing new farms in Pennsylvania and New York.

Some breeders are already building genetics programs around these requirements. Jersey and Jersey-cross genetics perform well in grazing systems due to component density and moderate frame size. Scandinavian Red influence—Norwegian Red, Swedish Red, VikingRed—contributes health and fertility traits developed under Nordic grazing conditions. Careful selection within Holstein for grazing efficiency, emphasizing moderate stature, strong feet and legs, and metabolic resilience, can effectively serve this market segment.

For breeders positioned to develop genetics suited explicitly to these systems, there’s an addressable market that larger programs haven’t captured.

The Mid-Size Challenge—And an Unexpected Opportunity

What’s becoming clear is that genetics questions can’t be separated from broader farm economics. Many mid-size operators are navigating this tension daily.

Industry analysts have observed that dairies without defined strategic plans tend to lose equity gradually through deferred maintenance, inefficiency, and missed opportunities—a pattern that compounds over time. It’s the gradual erosion that proves most damaging.

A 600-cow operator from southern Minnesota described it well at a Dairy Strong conference session: “We thought doing nothing was the safe move. Turns out, the slow leak was killing us.”

USDA data shows significant dairy consolidation continued through 2024, with over 1,400 operations exiting, resulting in a roughly 5 percent annual decline. Many of those closures were concentrated among mid-size operations caught between rising costs and tighter credit without the scale advantages of larger competitors.

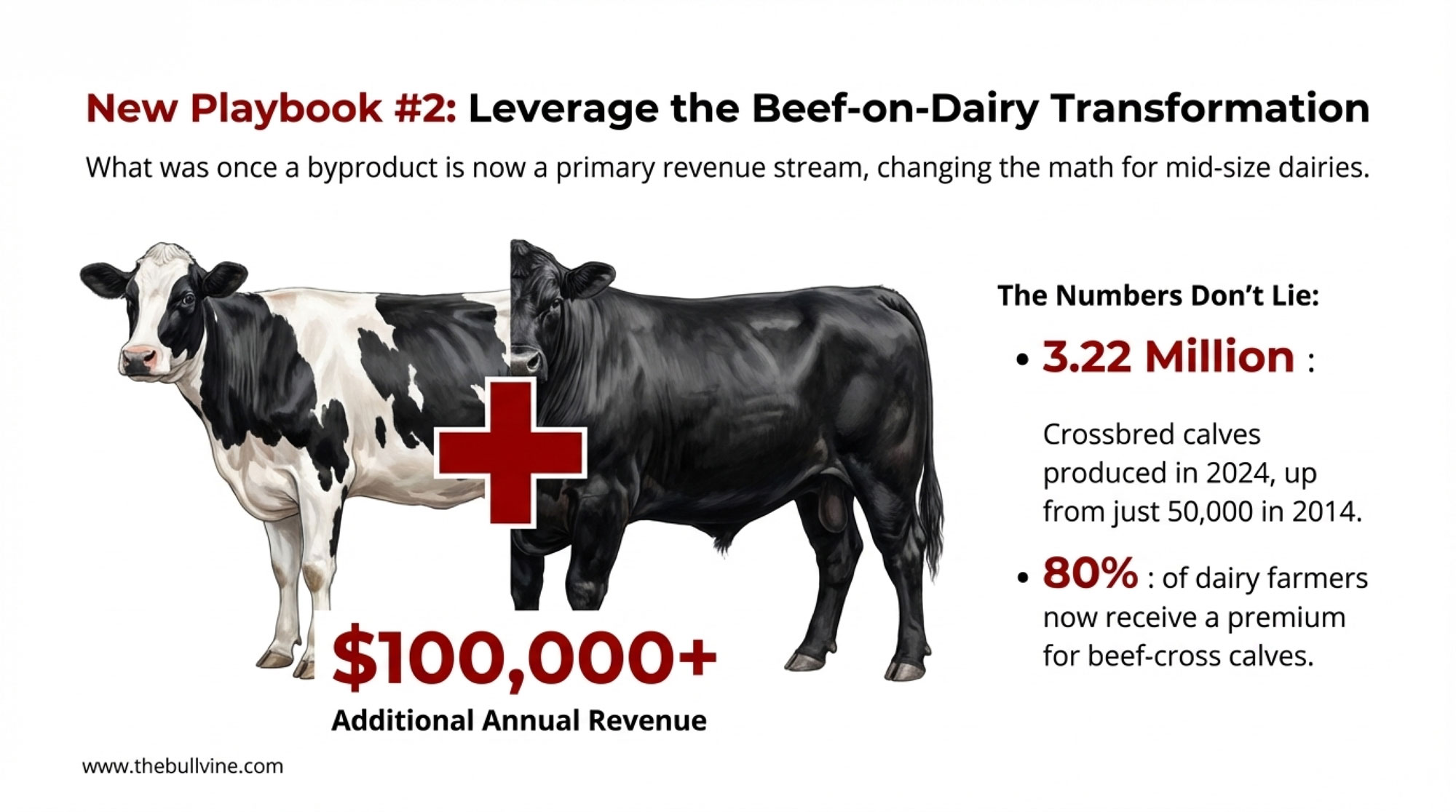

But here’s something that’s changed the math for a lot of those 600-cow herds: beef-on-dairy. The numbers have gotten hard to ignore.

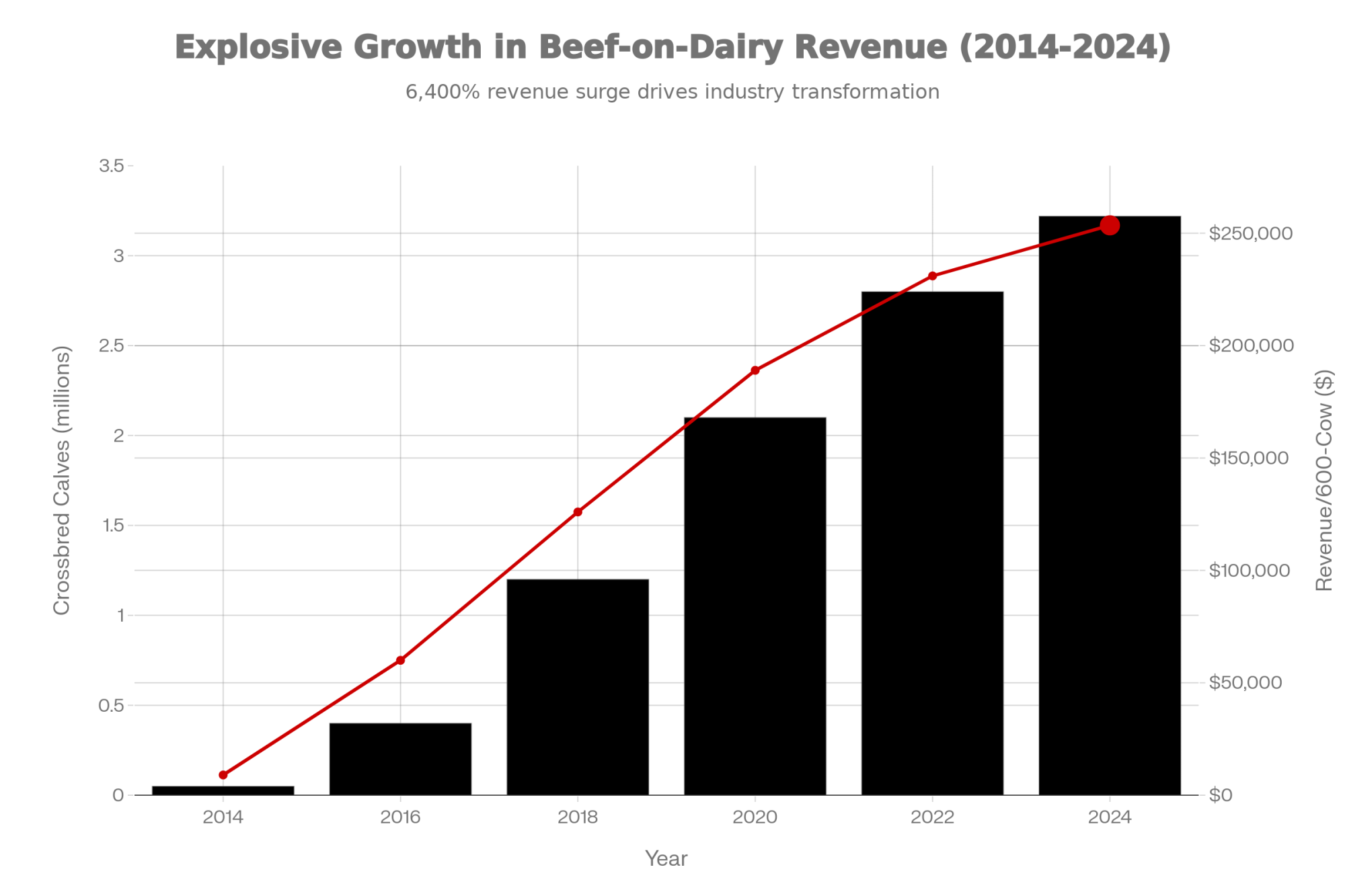

CattleFax estimates that crossbred calf production exploded from just 50,000 head in 2014 to 3.22 million in 2024, according to American Farm Bureau analysis. That’s not a trend—that’s a transformation. A 2024 Purina survey found that 80 percent of dairy farmers now receive a premium for beef-on-dairy calves, with reported revenues of $350 to $700 per head over straight dairy calves. USDA-verified auction reports show beef-cross calves selling for $680 to $1,160 per head at markets like New Holland, Pennsylvania.

| Year | Crossbred Calves Produced (millions) | Revenue per 600-cow herd ($) |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 0.05 | $9,000 |

| 2016 | 0.4 | $60,000 |

| 2018 | 1.2 | $126,000 |

| 2020 | 2.1 | $189,000 |

| 2022 | 2.8 | $231,000 |

| 2024 | 3.22 | $253,500 |

For mid-size operations, the economics add up quickly. University of Wisconsin research led by Dr. Victor Cabrera found that herds maintaining 30 percent or higher pregnancy rates can generate over $6,200 in net calf income per month through optimized beef-on-dairy programs. University extension services are documenting operations that implemented beef-on-dairy strategies in early 2024, projecting $100,000 to $150,000 in additional annual revenue from crossbred calves alone.

The genetics piece matters here, too. Beef semen sales to dairy operations reached 7.9 million units in 2024, according to NAAB data—up dramatically from 3.7 million total beef units in 2014. That creates demand for breeders who understand both sides of the equation: which beef genetics produce calves that finish efficiently, grade well, and don’t create calving problems on Holstein or Jersey dams.

This isn’t the traditional seedstock model, but it’s a way mid-size operations can leverage genetic knowledge to generate real revenue without competing directly with corporate nucleus herds for elite dairy genetics.

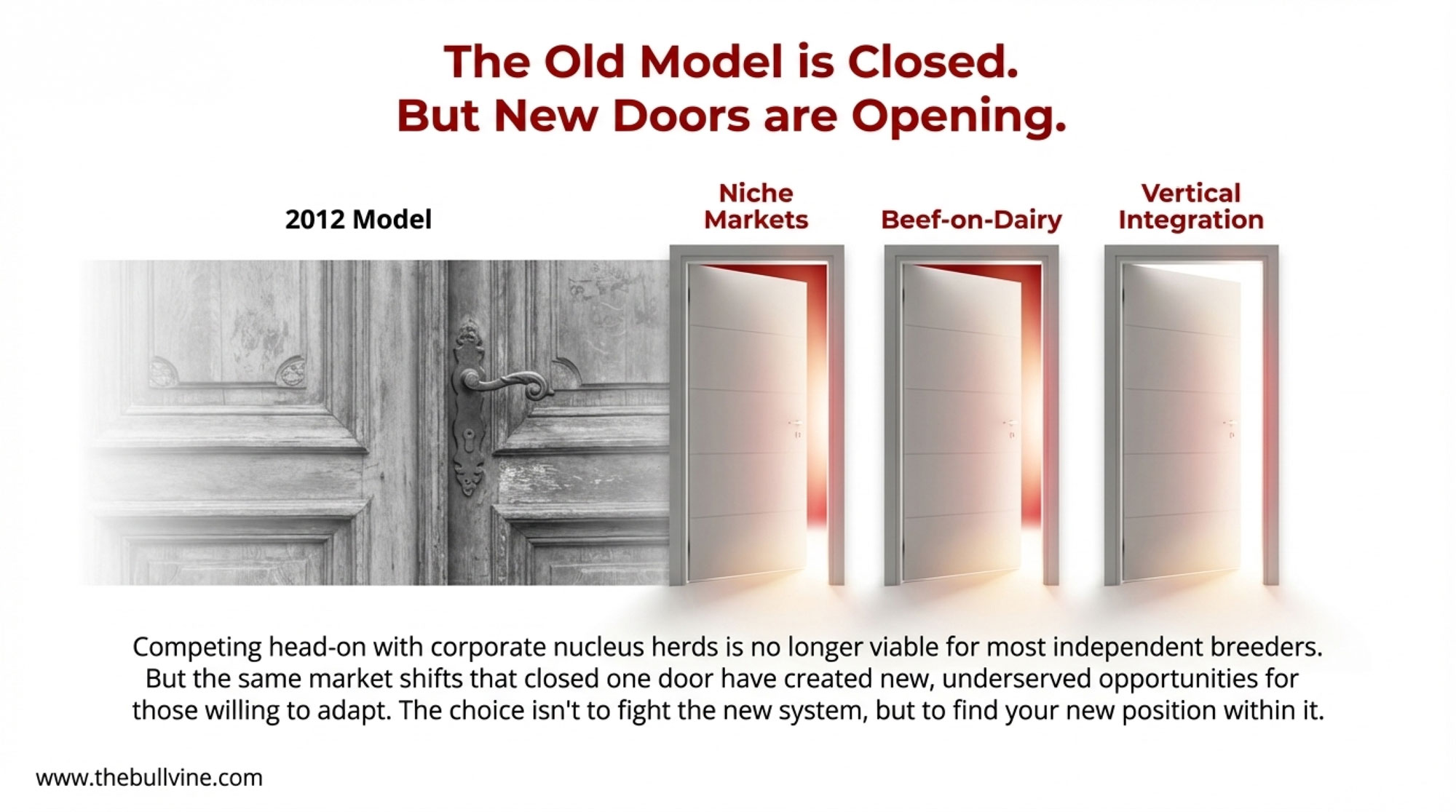

For seedstock operations specifically, the challenge compounds differently: genetic income has compressed while production economics have tightened simultaneously. The wait-and-see approach carries increasing risk. But diversification—whether into grass-fed genetics, beef-on-dairy optimization, or vertical integration—offers paths forward that pure dairy genetics increasingly doesn’t.

A Note on Regional Dynamics

Most of what I’ve covered here reflects the reality for operations in the Upper Midwest and Northeast—where the traditional seedstock model developed and where most family breeding operations still operate. But it’s worth acknowledging that dairy economics look quite different in other parts of the country.

According to Progressive Dairy statistics, dairy herds averaged more than 2,000 head in several Western states—including New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas—while seven additional states averaged more than 1,000 head. The locational contrast is stark—states with small herds are concentrated entirely in the Midwest and Northeast, while Western dairy states operate at substantially larger scale.

Texas added 50,000 cows to its dairy herd in just 12 months, growing from 640,000 to 690,000 head according to USDA state-level data. That single-state expansion accounted for 56 percent of the entire national herd growth in 2024. Idaho ranked fourth nationally in milk production, accounting for about 7.5 percent of U.S. output, according to Capital Press reporting. Meanwhile, Kansas posted 11.4 percent production growth, emerging as another major expansion center.

California remains the national leader with 1.7 million cows and a $23.2 billion economic contribution to state GDP in 2024, according to the California Milk Advisory Board and UC Davis research. But the state’s regulatory environment—including methane reduction mandates and LCFS credit changes—is creating consolidation pressure that an ERA Economics analysis suggests could push 20 to 25 percent of small California dairies to exit.

These Western mega-dairy operations face different genetics decisions than a 200-cow Wisconsin seedstock farm. Their scale allows direct negotiation with AI companies, in-house reproductive programs, and purchasing power that smaller operations can’t match. The consolidation dynamics—and the opportunities for independent breeders—may look quite different in those markets.

We’re planning a follow-up piece exploring how genetics economics play out differently in California’s mega-dairy environment and the rapidly expanding Texas and Idaho sectors. If you’re operating in those regions and have insights to share, reach out—we’d like to hear your perspective.

Strategic Options Worth Considering

Looking at what’s working for breeding operations in this environment, several approaches show promise. The right choice depends on individual circumstances, available capital, and where you see opportunity.

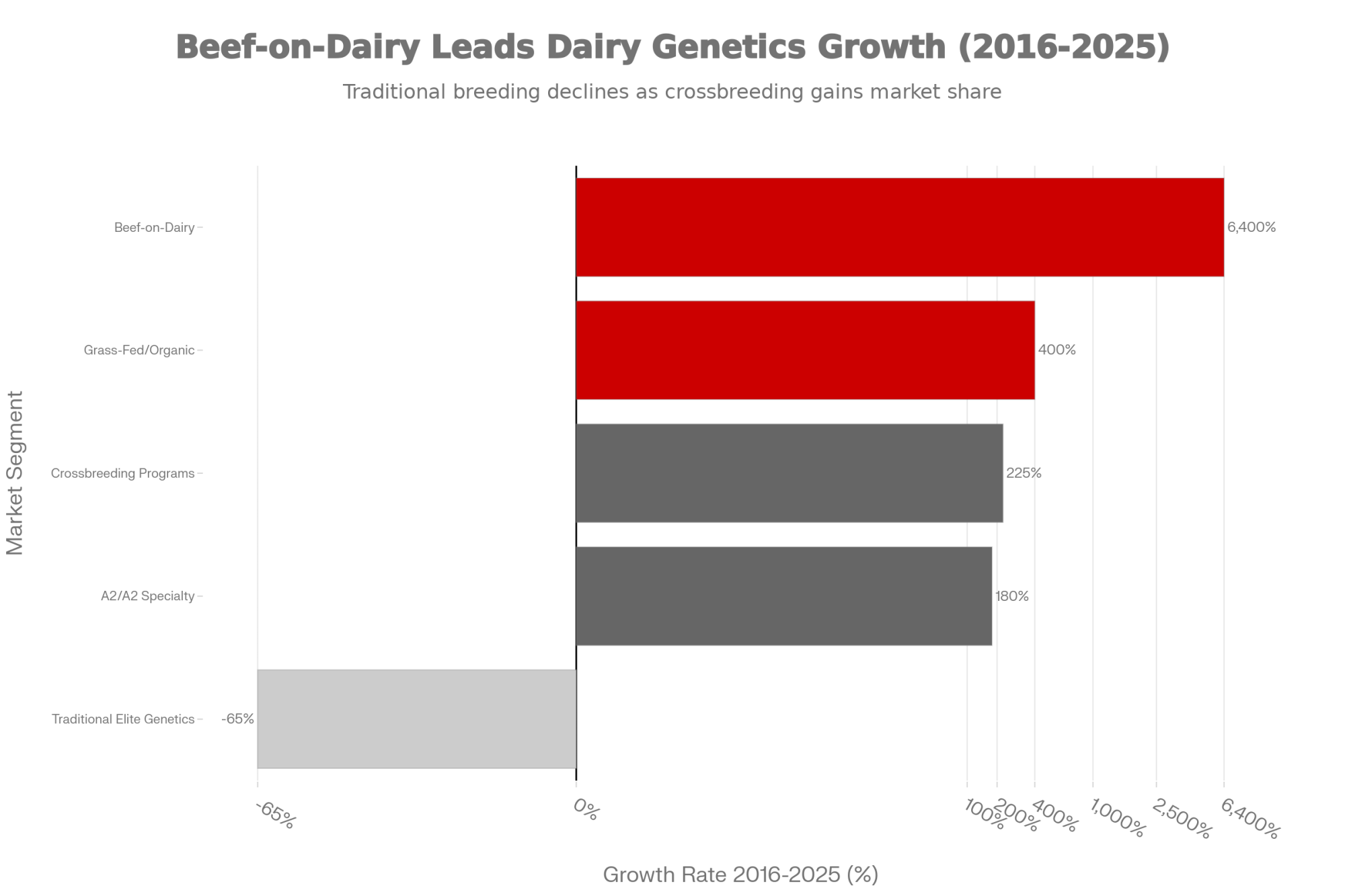

| Market Segment | Growth Rate 2016-2025 (%) | Corporate Dominance (%) | Breeder Opportunity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Elite Genetics | -65% | 95% | Limited |

| Grass-Fed/Organic | +400% | 15% | Strong |

| Beef-on-Dairy | +6,400% | 25% | Strong |

| A2/A2 Specialty | +180% | 30% | Moderate |

| Crossbreeding Programs | +225% | 20% | Moderate |

Premium market specialization means building genetics for segments that corporate programs underserve. Grass-fed, organic, A2/A2 milk, alternative breeds for specific production systems—these markets are smaller but growing faster than commodity dairy, and they offer pricing flexibility that commodity genetics typically don’t provide.

The capital requirements are substantial. Current market conditions suggest a range of $2 to $5 million to build a competitive reference population and marketing infrastructure. But the economics can work for well-positioned operations. A heifer bred specifically for grass-fed systems might command $5,000 to $8,000 versus $2,500 to $4,000 for a comparable commodity Holstein. Embryos can move at $1,500 to $3,000 rather than $500 to $800.

Cooperative and collaborative models draw inspiration from European structures such as the Alpine Genetic Evaluation Team, which coordinates breeding programs across multiple countries through shared infrastructure, phenotype recording, and research partnerships. This approach requires substantial coordination and typically depends on public research support, making North American implementation more challenging. But it represents a proven alternative for breeders willing to invest in collective infrastructure.

Vertical integration means using elite genetics to build your own production operation rather than relying on genetic sales as your primary source of revenue. Income flows perhaps 80 percent from milk or beef, 20 percent from surplus genetics. You become your own multiplier, independent of external semen sales volatility.

Strategic exits remain viable for operations with genuinely elite bloodlines. Corporate genetics companies are active acquirers. Breeders with exceptional genetics may find that well-timed sales—whether specific cow families or entire herds—capture more value than competing independently in consolidated markets.

Which Path Fits Your Operation?

| If Your Operation Has… | Consider This Strategy | Key Requirements | Timeline Pressure |

| Strong cow families + limited capital | Premium market specialization (grass-fed, organic, A2) | Market research, breed adaptation, and direct customer relationships | Moderate—market growing, but competition emerging |

| Regional network + shared values | Cooperative model | Coordination capacity, public research partnerships, and long-term commitment | Low—but requires a 3-5 year development horizon |

| Elite genetics + production infrastructure | Vertical integration | Milk market access, management bandwidth, and capital for expansion | Low—can implement gradually |

| Top-tier bloodlines + exit timeline | Strategic sale to an AI company | Professional valuation, legal counsel, and timing awareness | High—value erodes as consolidation continues |

| Mid-size herd + reproductive efficiency | Beef-on-dairy optimization | Pregnancy rate management, beef sire selection knowledge, and calf marketing | Low—can start immediately |

| Under $200K genetics revenue + no clear edge | Accelerated decision | Honest assessment, financial planning, family alignment | Critical—12-month decision window |

What the Numbers Suggest Going Forward

Fortune Business Insights projects the global animal genetics market will grow from $8.31 billion in 2024 to $14.78 billion by 2032. That growth will flow predominantly through corporate channels—the infrastructure investments are already in place, and competitive advantages compound over time.

For commercial dairy farmers focused on milk production, the consolidated system delivers genuine value: faster access to genetics, sophisticated breeding tools, and reduced complexity in sourcing genetics. The August 2025 CDCB evaluations showed continued progress on production, health, and fertility traits. That benefits most producers directly.

For breeding operations, the calculation differs. The traditional model—developing elite genetics and capturing value through semen sales, embryo production, and female marketing—faces structural headwinds unlikely to reverse.

Practical Implications

For commercial operations:

- Current genetics delivery systems offer real advantages in accessibility and genetic progress

- Match selection to your specific production system and management approach

- Monitor inbreeding levels when making mating decisions, particularly in purebred Holstein programs—Lactanet’s inbreeding calculator and similar tools help identify concerning combinations

- Consider whether alternative breeds or crossbreeding strategies might benefit your specific goals

For seedstock operations:

- Operations generating under $200,000 in genetic revenue need a 12-month decision timeline—not a five-year plan

- Evaluate niche market positioning in segments where corporate programs are less dominant

- Assess whether vertical integration economics compare favorably to a continued genetic sales focus

- Review contract terms thoroughly before committing to elite genetics programs

- Recognize that strategic options narrow as consolidation continues—the window for positioning is measured in years, not decades

For the industry broadly:

- Genetic diversity management deserves increased attention as selection intensity rises

- Public genetic evaluation systems like CDCB and Lactanet remain valuable reference points alongside proprietary indices

- Alternative breeding approaches, even at a smaller scale, provide resilience and options that pure consolidation doesn’t

The Bottom Line

The dairy genetics industry has always evolved. Proven sires gave way to genomics, conventional AI gave way to IVF, and distributed breeding gave way to concentrated nucleus herds. Each transition created winners and losers, opportunities and challenges.

What distinguishes this moment is the pace of change and the scale of capital required to remain competitive at the elite level. Understanding that reality—neither resisting it nor ignoring it—is the starting point for any strategic decision about where breeding fits in your operation’s future.

The genetics are better than they’ve ever been. The infrastructure to deliver them has never been more sophisticated. And for producers willing to work within the new system, access has never been easier.

But if you’re a breeder who built something over generations—who selected, culled, tested, and refined bloodlines that carry your family’s name—the question isn’t whether the new system works. It’s whether there’s still a place in it for you.

That answer isn’t written yet. But the window to write it yourself is closing faster than most people realize.

Key Takeaways

- The money moved—it didn’t vanish — Seedstock revenue dropped from $1.5M to $150K for many operations. Value shifted to corporate infrastructure because technology changed who captures genetic gains—not because the genetics got worse.

- Read the contracts before you sign — Elite programs often transfer semen rights, lock in female purchase options at preset prices, and claim perpetual licenses to your genomic data. Know whether you’re sharing in value creation or just supplying raw material.

- Inbreeding carries a real cost — Holstein heifers now average nearly 10% inbreeding. At $22-24 per cow per lactation per percentage point, this quietly offsets the genetic progress everyone’s celebrating.

- The old model closed—but new ones opened — Grass-fed genetics (400% market growth since 2016), beef-on-dairy programs ($100K+ annual revenue), and vertical integration are working for breeders who’ve repositioned.

- Your window is measured in months, not years — operations with $200K or less in genetics revenue need a 12-month action plan. Strategic options narrow as consolidation continues. Waiting is its own decision.

Executive Summary:

Here’s the reality facing dairy breeders: a seedstock operation that generated $1.5 million in genetics revenue a decade ago might see $150,000 today—even with better cows. The money didn’t disappear. It moved. Genomic testing and juvenile IVF compressed generation intervals from 36 months to 12, while corporate consolidation put companies like URUS and ABS Global in control of elite females, reproductive infrastructure, and genetic data. Commercial producers benefit through faster access to improved genetics at lower complexity. Independent breeders face a harder calculation—compressed margins, restrictive contracts, and rising inbreeding levels approaching 10% in Holsteins. But genuine opportunities exist for those willing to adapt: grass-fed and organic genetics serving a market that’s grown 400% since 2016, beef-on-dairy programs adding $100,000+ in annual revenue, and strategic repositioning before options narrow further. The window is measured in years, not decades. This analysis traces where value migrated, breaks down the contracts worth scrutinizing, and maps which paths are actually working for breeding operations in 2025.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The 90-Day Dairy Pivot: Converting Beef Windfalls into Next Year’s Survival – Arms you with the exact math to convert temporary $1,000 beef-on-dairy windfalls into long-term operational resilience. It reveals the $26,600 “stacking” opportunity that mid-size dairies must capture before the current market window slams shut in 2026.

- Bred for $3 Butterfat, Selling at $2.50: Inside the 5-Year Gap That’s Reshaping Genetic Strategy – Exposes the dangerous five-year lag between your genetic selections and bulk tank reality. It delivers a blueprint for building a “market-agnostic” herd that survives commodity price flips through health traits and extended productive life.

- The McCarty Magic: How a Family Farm Became the Dairy Industry’s Brightest Star – Breaks down the high-stakes strategy of on-farm processing and vertical integration used to scale from 15 to 20,000 cows. It gives you the roadmap for capturing the value chain through the “DIRT” management principles and 75% logistics savings.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!