The diagnostic protocol and implementation timeline that’s turning wasted nitrogen into profit

Executive Summary: That extra 2% crude protein in your ration isn’t insurance—it’s a $40,000 annual drain on a 300-cow dairy. Research from Penn State, Cornell, and USDA confirms that properly balanced 15-16.5% protein diets match production while eliminating wasted nitrogen that hits your feed bill and your conception rates. Stack protein optimization with zero-cost heifer separation and proper silage timing, and the combined opportunity reaches $130,000-$160,000 per year. The risk: cutting protein without proper diagnostics can trigger intake depression and lost milk. This guide delivers the 4-step diagnostic protocol that’s working on progressive operations—plus an 18-month implementation timeline, fresh cow exceptions, and clear guidance on when to hold back. The goal isn’t minimum protein. It’s the maximum profit per cow.

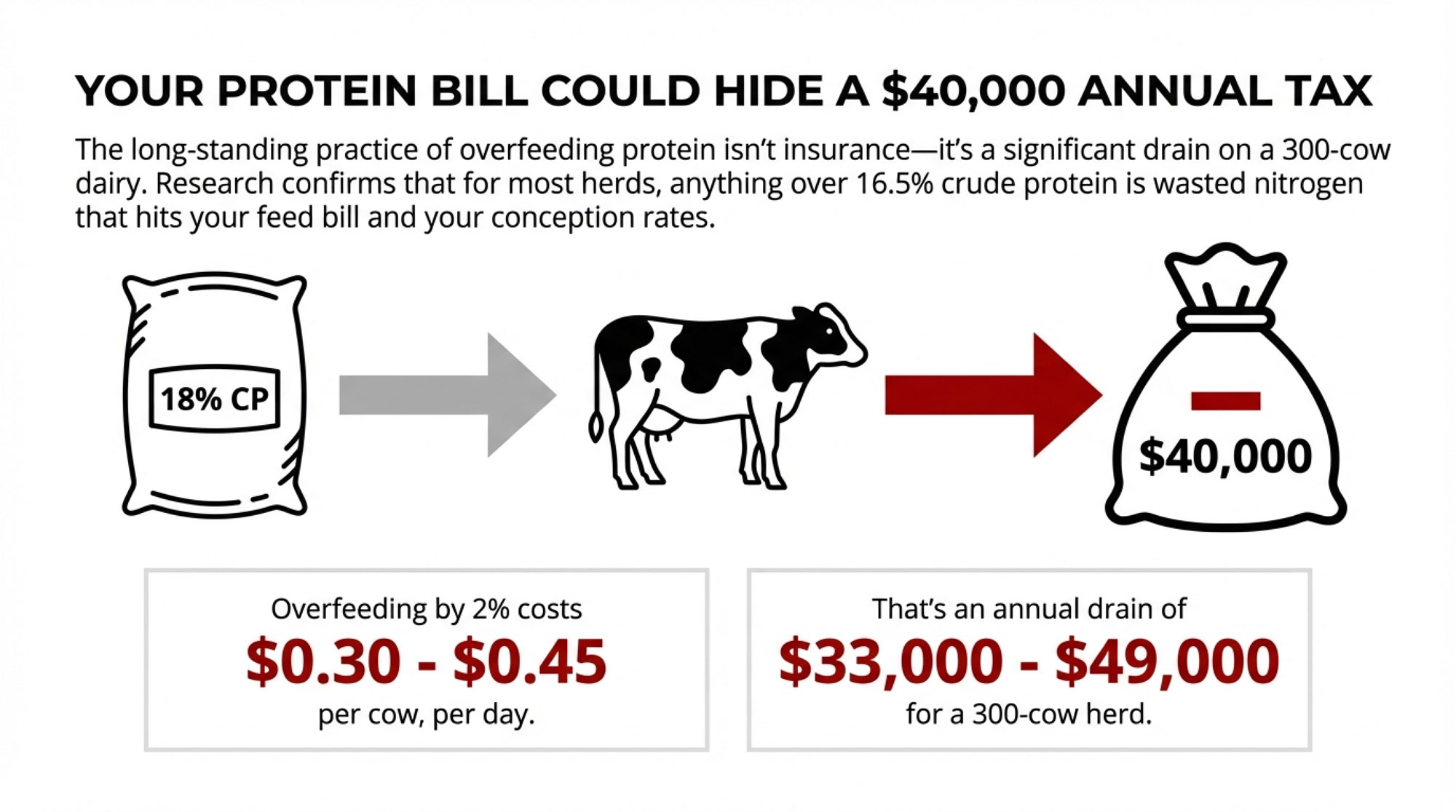

What if I told you that 2% of your crude protein is actually a $40,000 hidden tax on your 300-cow herd? That’s the conversation I keep having with producers across North America, and it’s worth exploring carefully.

The central issue comes down to protein. Specifically, the long-standing practice of feeding more than cows can efficiently utilize.

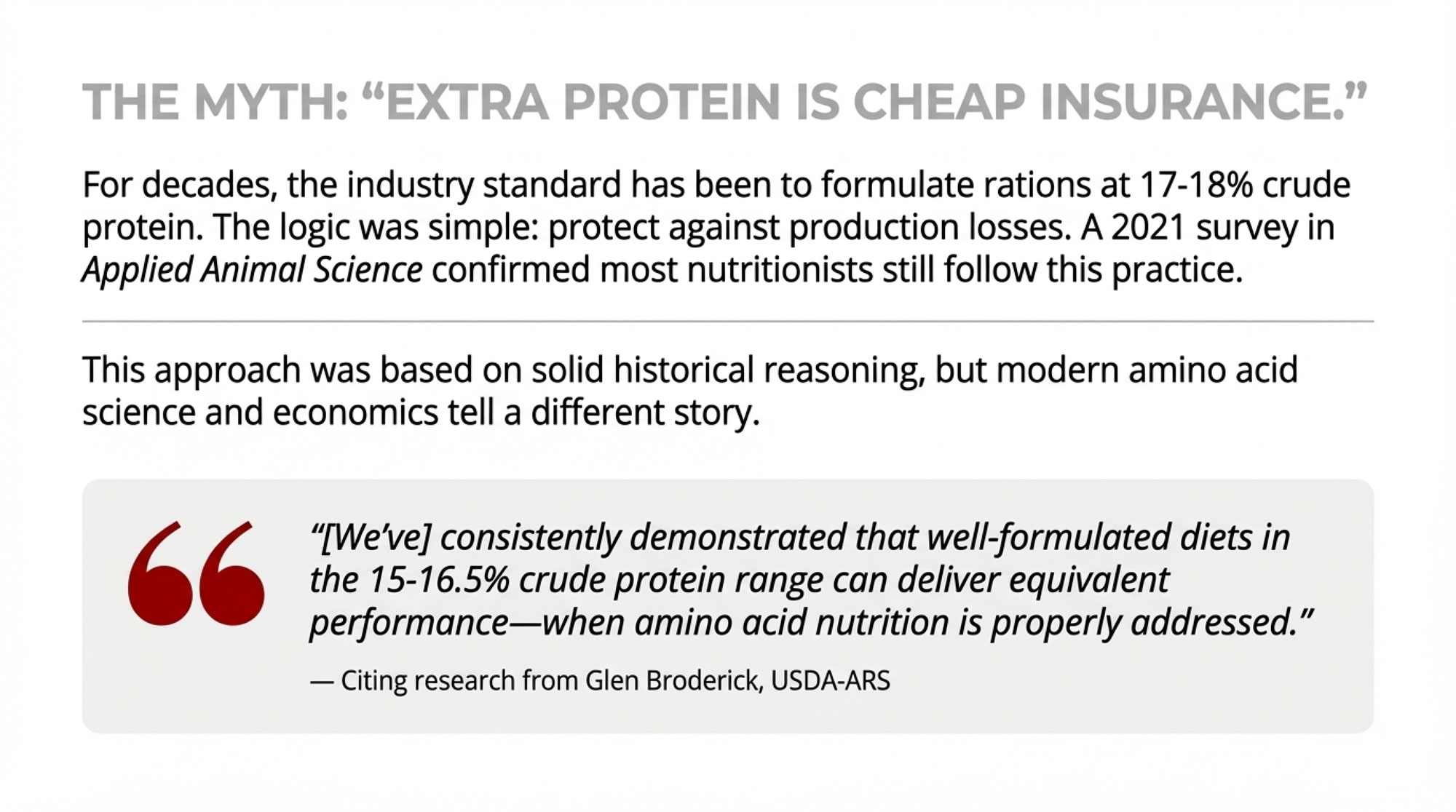

When Applied Animal Science published a survey of U.S. dairy nutritionists in 2021, the findings confirmed what most of us suspected—the majority still formulate lactating cow rations at 17-18% crude protein. There are solid historical reasons for that approach. Protein has always been viewed as insurance against production losses.

But here’s where the conversation gets interesting. Foundational research from scientists like Glen Broderick at USDA’s Agricultural Research Service has consistently demonstrated that well-formulated diets in the 15-16.5% crude protein range can deliver equivalent performance—when amino acid nutrition is properly addressed. That qualifier matters.

The economics become clearer once you work through the numbers. Protein remains one of the most expensive components of the ration. When cows receive more than their metabolism can utilize, the liver converts that surplus nitrogen to urea—an energy-intensive process that diverts calories away from productive purposes. That urea shows up in three places: elevated Milk Urea Nitrogen readings, increased nitrogen loading in the manure lagoon, and higher numbers on the feed bill.

Understanding the Financial Picture

For a 300-cow operation—and I’ve worked through these calculations with producers in several regions—the potential impact deserves attention. Current feed prices vary considerably by geography, but overfeeding crude protein by two percentage points typically costs $0.30-0.45 per cow per day in direct feed expenses.

Annually, that represents roughly $33,000 to $49,000 in potential savings from optimization alone. Whether those savings are fully achievable depends on your specific situation, which is why working with a qualified nutritionist matters so much.

And that’s before considering the reproductive implications.

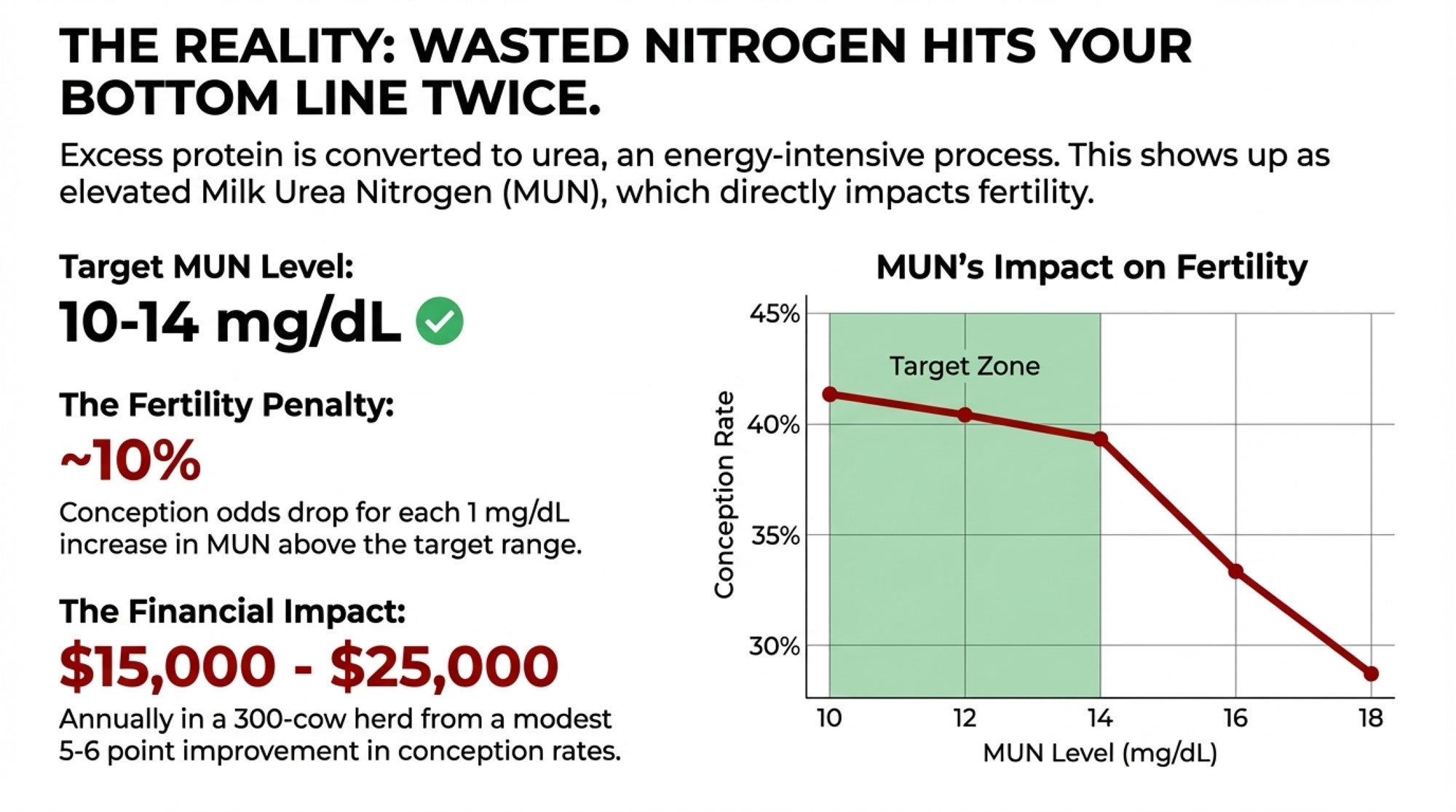

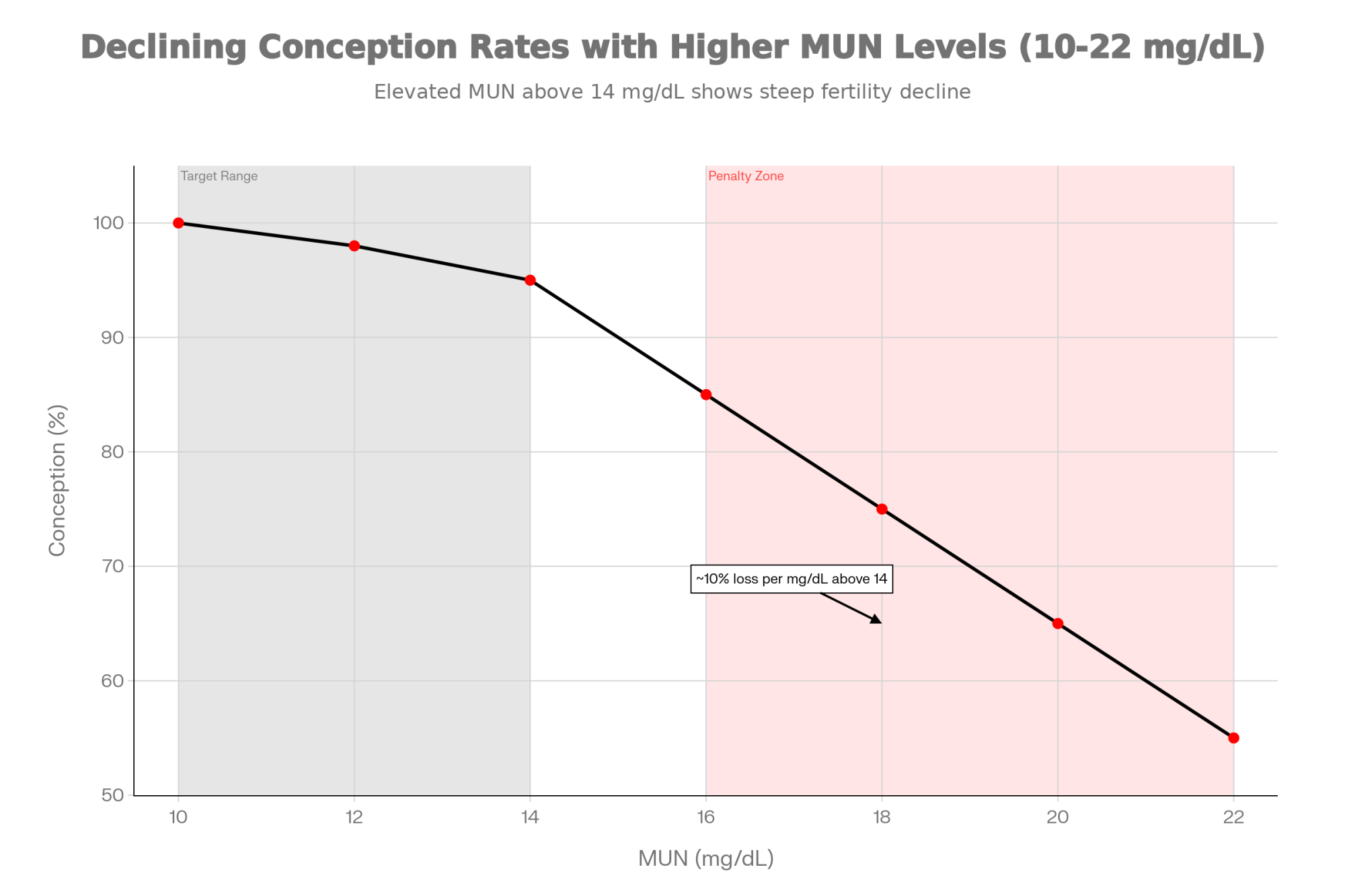

Research from Cornell University and the University of Wisconsin has established connections between elevated MUN levels and reduced fertility. Studies published in Animal Reproduction Science found that cows with MUN concentrations above 16 mg/dL showed notably lower pregnancy rates—approximately 14% reduction in some trials. That’s meaningful when you’re working to maintain reproductive efficiency.

The biology here is reasonably well understood. Elevated circulating ammonia and urea can alter the uterine environment, compromising embryo development. Penn State’s extension service recommends targeting MUN in the 10-14 mg/dL range, and research suggests approximately a 10% reduction in conception odds for each 1 mg/dL increase above that target.

What does that mean practically? A 300-cow operation seeing even modest conception rate improvements—say 5-6 percentage points—could realize $15,000-$25,000 annually in reduced days open, lower breeding costs, and fewer replacement purchases. The exact figures depend heavily on your replacement costs and current reproductive performance.

Why the Transition Takes Careful Thought

Given the potential economics, it’s fair to ask why more operations haven’t pursued protein optimization. The nutritionists I’ve spoken with offer thoughtful perspectives.

The Applied Animal Science survey identified “fear of decreased dry matter intake” as the primary concern when formulating lower-protein diets. And honestly, that concern has merit.

Dr. Alex Hristov’s research group at Penn State has done extensive work in this area, and their findings confirm there’s a real threshold below which performance suffers. In long-term trials, diets containing approximately 14% or less crude protein resulted in decreased intake, even when amino acid balance was addressed. At the 2024 Florida Ruminant Nutrition Symposium, their work highlighted that supplementation with rumen-protected histidine improved performance on low-protein diets—underscoring the amino acid’s critical role.

I recently spoke with an Ontario nutritionist who put it this way: “I’ve seen operations run successfully at 15% crude protein, and I’ve also seen farms struggle at 16% because their forage base couldn’t support it. The tipping point varies by herd.”

That variability is exactly why blanket recommendations can be problematic. Every operation has different forages, different genetics, and different management systems.

There’s another consideration worth acknowledging. Dr. Chuck Schwab, Professor Emeritus at the University of New Hampshire and a leading voice on amino acid nutrition, has been appropriately cautious about some rumen-protected amino acid products. Not all have been rigorously evaluated for bioavailability using in vivo methods, which means nutritionists sometimes formulate without complete confidence in how much amino acid is actually being absorbed. That uncertainty makes some advisors understandably careful.

A Measured Approach That’s Working

The operations successfully navigating this aren’t making dramatic overnight changes. They’re following methodical processes that identify their specific herd’s optimal range before making adjustments that could affect production.

What does that look like in practice? I walked through the process recently with a California producer running 400 cows who’s been fine-tuning his approach over the past 18 months.

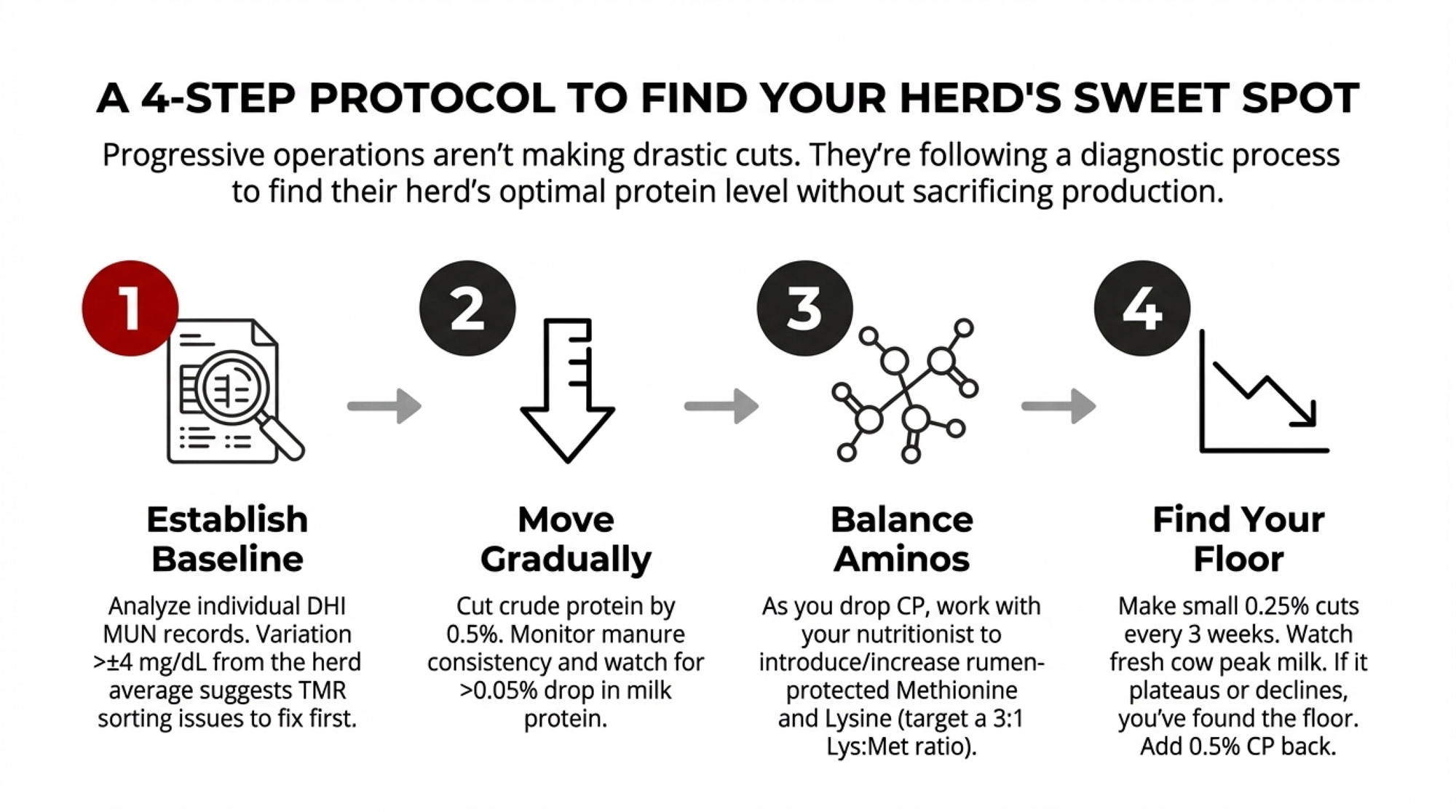

- Establish your baseline first. Before any dietary changes, examine individual MUN records from DHI testing. Cornell’s PRO-DAIRY program suggests that 75% or more of cows should fall within ±4 mg/dL of the herd average. Wide variation—some cows at 8 mg/dL while others hit 22 mg/dL on the same ration—usually indicates mixing or sorting issues to address first. “We discovered our TMR wasn’t as consistent as we thought,” that California producer told me. “Had to fix that before anything else made sense.”

- Move gradually. Reduce dietary crude protein by 0.5 percentage points while maintaining amino acid levels. Monitor manure consistency and milk protein percentage carefully. Slightly firmer manure often indicates less nitrogen waste. But if the milk protein percentage drops by more than 0.05% in the first week, you may have reduced rumen-degradable protein too aggressively.

- Address amino acid nutrition simultaneously. When dropping crude protein further, consider introducing or increasing rumen-protected methionine and lysine. Published research suggests targeting a ratio of approximately

for Lysine to Methionine, with roughly 7.2% lysine and 2.4-3.2% methionine as a percentage of metabolizable protein. Your nutritionist can help fine-tune these targets.

- Find your floor carefully. Continue modest reductions—perhaps 0.25% increments every three weeks—while watching fresh cow peak milk as a key indicator. Fresh cows have the highest amino acid requirements. When peaks plateau or decline, you’ve found your floor. Add back half a percentage point immediately.

| Diet Type | Crude Protein (%) | Risk Profile | Annual Cost (300-cow herd) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Industry Standard | 17-18% | Low risk, high nitrogen waste | Baseline + $40,000 |

| Aggressive Low (Risky) | 14% or less | High risk—intake depression likely | May lose production |

| Optimized Target Range | 15-16.5% | Balanced—when amino acids addressed | Saves $33,000-$49,000 |

| Fresh Cow Exception | 19% | Supports metabolic transition | Worth the premium |

Most operations following this approach discover their sustainable range is 1.5 to 2.0 percentage points below their starting point. But the key word is “sustainable”—the goal isn’t to reach the lowest possible number; it’s to find where your specific herd performs optimally.

Fresh Cows Require Different Thinking

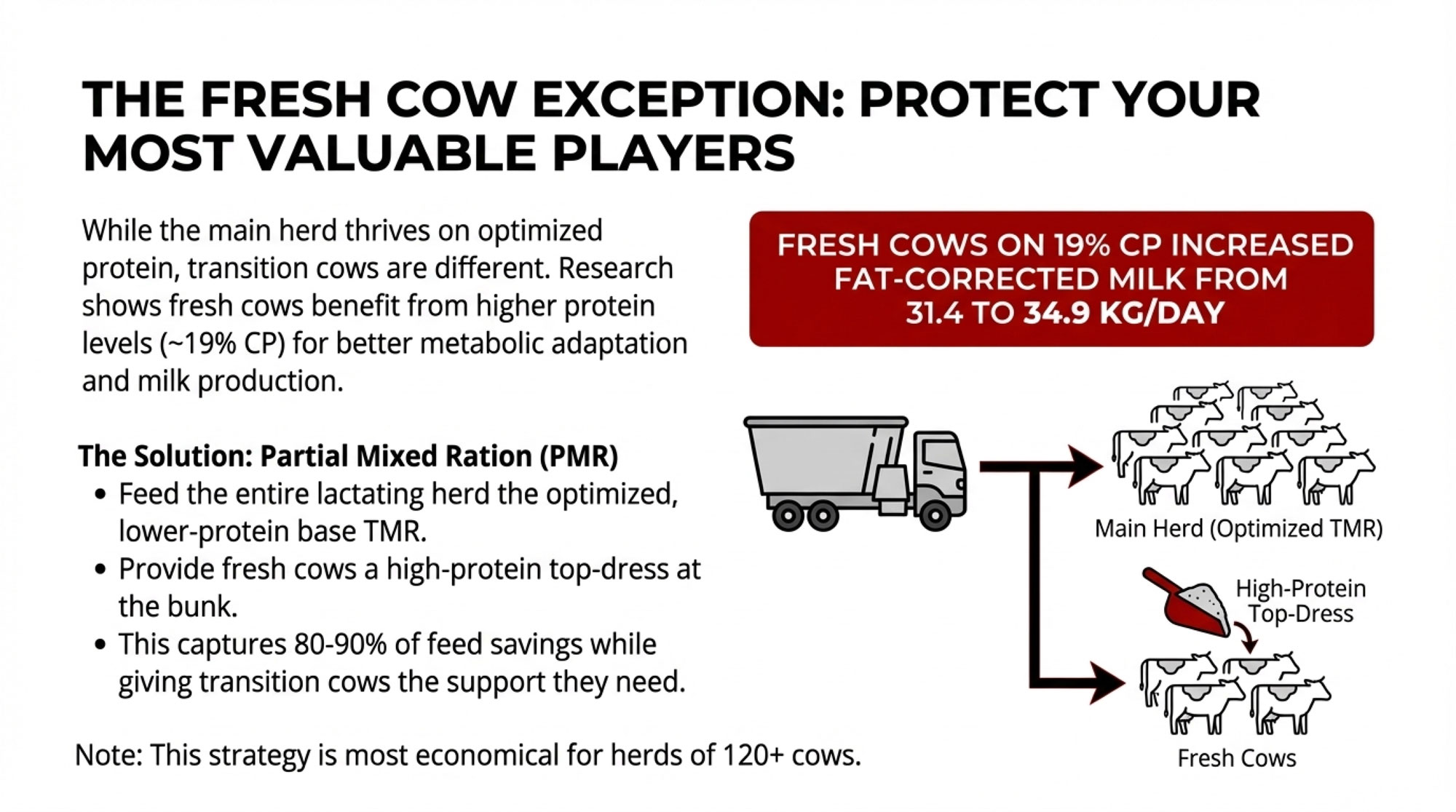

Here’s where the conversation takes an important turn. While mid-lactation cows may thrive on optimized protein levels, transition cows appear to benefit from more generous protein nutrition.

Recent research found that fresh cows receiving approximately 19% crude protein increased fat-corrected milk substantially—from 31.4 to 34.9 kg/day in one study. Those same animals showed reduced body condition loss and improved metabolic markers (lower NEFA and BHB concentrations), suggesting better adaptation to the demands of early lactation.

Dr. Masahito Oba’s work at the University of Alberta supports this general pattern, though he notes that research on rumen-protected amino acid supplementation during transition has yielded inconsistent results. The physiology of transition cows is complex, and we’re still learning how best to support them nutritionally.

So how do you capture efficiency gains on the main herd while protecting vulnerable fresh cows?

Many operations are finding success with a Partial Mixed Ration approach. Rather than preparing completely separate batches—which creates logistical headaches and often exceeds mixer capacity for small fresh pen loads—they feed the entire lactating herd a base ration at the optimized protein level. Fresh cows then receive a high-protein top-dress at the bunk.

This captures most of the potential savings (since 80-90% of cows consume the efficient ration) while providing transition animals the metabolic support they need.

The economics suggest that somewhere around 120 lactating cows represents a rough threshold where the management complexity pays for itself. Smaller operations may find the labor hard to justify. Larger herds—150 cows and above—that remain on a single high-protein ration may be leaving meaningful money on the table.

A High-Return Strategy That Requires No Ration Changes

One finding that consistently surprises producers: one of the most impactful changes doesn’t involve the feed sheet at all.

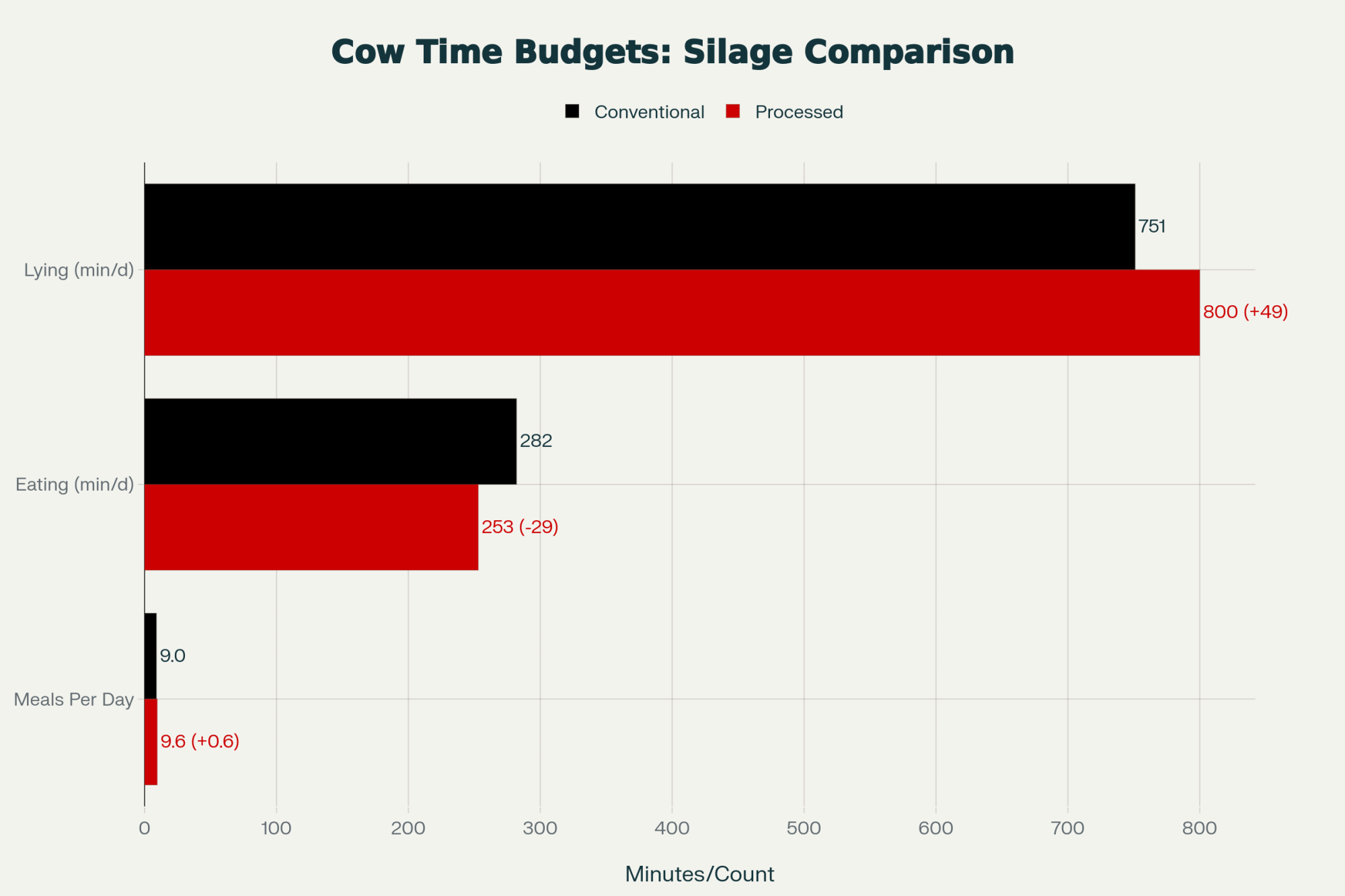

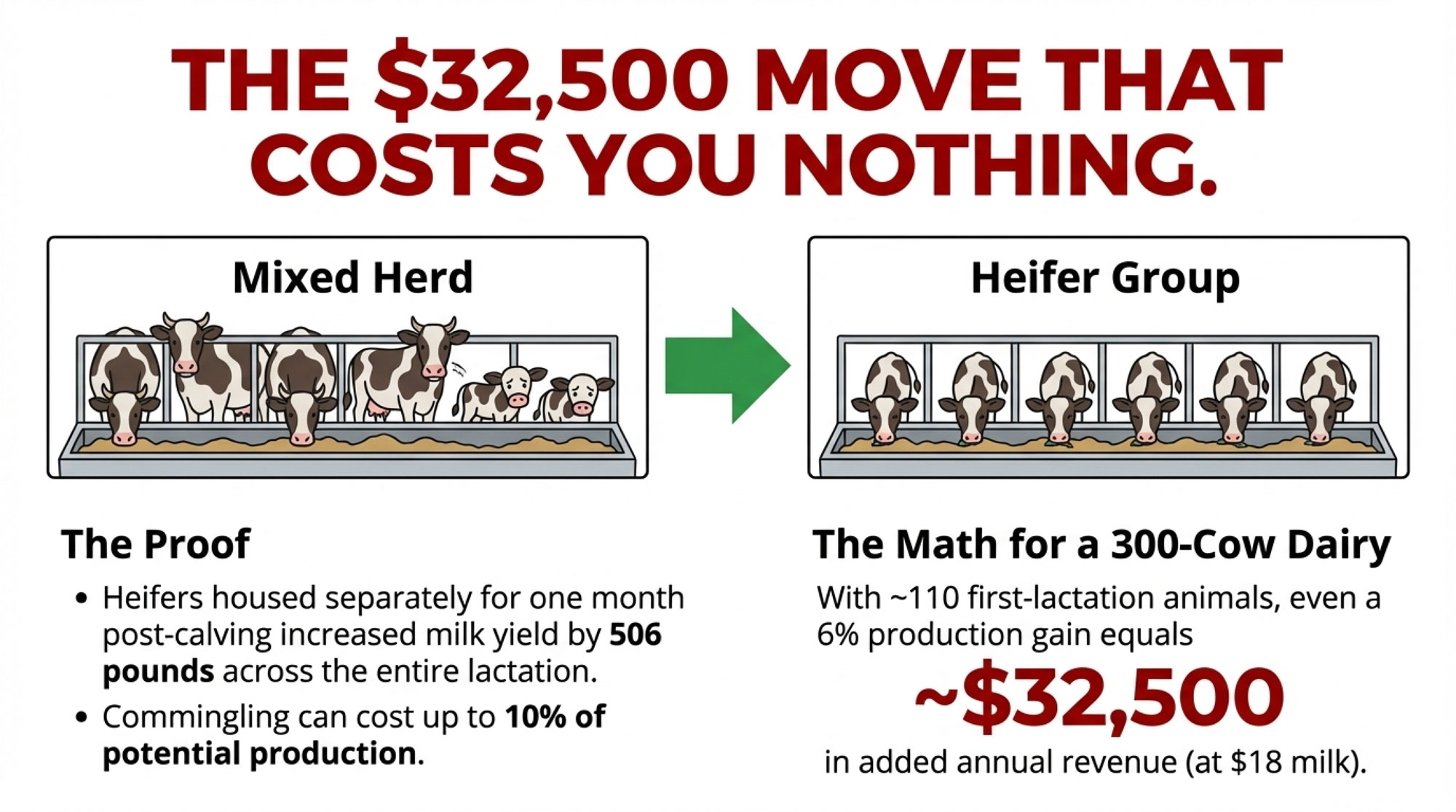

Separating first-lactation animals into their own group—even on identical nutrition—regularly delivers measurable production improvements. Research from multiple university programs, including work highlighted in Hoard’s Dairyman, has confirmed that first-lactation heifers housed apart from mature cows show reduced competitive stress and improved feeding patterns.

European researchers documented that heifers housed separately for just one month after calving increased milk yield by 506 pounds across the lactation. Classic studies suggest farms may sacrifice close to 10% of potential production when parities are commingled—a substantial penalty for something that costs nothing to address.

The mechanism is behavioral, and as many of us have seen watching bunk activity, first-lactation animals naturally prefer smaller, more frequent meals. Mature cows tend toward larger, less frequent consumption. When housed together, dominant animals control access to the bunk during the critical period after fresh feed delivery. Younger cows respond by eating faster (which destabilizes rumen pH) and resting less (which reduces rumination time).

For a 300-cow dairy with roughly 110 first-lactation animals, even a 6% production improvement translates to approximately $32,500 in additional annual revenue at $18 milk. No equipment investment, no ration reformulation—just a management decision about pen assignments.

| Management System | Lactation Yield Impact | Annual Value (300-cow herd) | Additional Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed Parity Housing | Baseline (100%) | $0 | None |

| Heifers Separated (1 month) | +506 lbs/lactation | $16,000-$20,000 | Zero |

| Heifers Separated (Full lactation) | +800-1,000 lbs/lactation (est) | $25,000-$32,500 | Zero |

| European Research Average | +506 lbs/lactation | $16,000-$20,000 | Zero |

A Wisconsin producer I spoke with made this change two years ago. “We were skeptical at first,” he told me. “Same feed, same barn, just different pens. But we saw results in the bulk tank within six weeks. The heifers settled into a better routine once they weren’t competing with older cows.”

I’ve heard similar stories from Northeast operations and California dairies. The specifics vary, but the pattern holds.

The Annual Decision That Creates Outsized Impact

While protein optimization and grouping strategies operate throughout the year, one seasonal decision carries disproportionate financial weight: corn silage harvest timing.

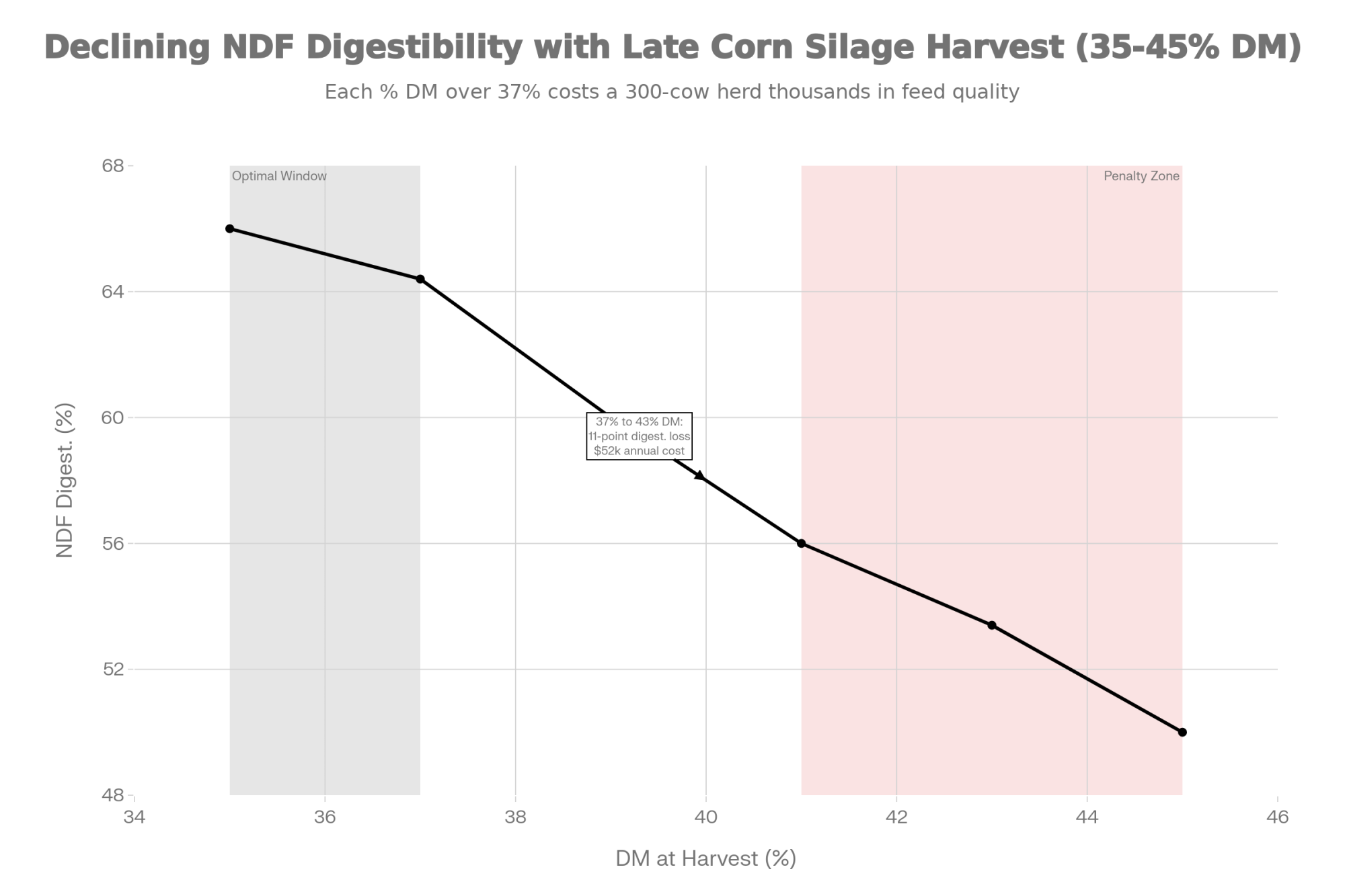

The Bottom Line on Harvest Timing: “Losing 11 points of NDF digestibility from delayed harvest costs more than $52,000 annually for a 300-cow dairy. That’s money lost in a few autumn days that you can never recover.”

Research published in Translational Animal Science quantified what many producers have observed. As harvest gets pushed from 37% to 43% dry matter, NDF digestibility declined from 64.4% to 53.4%. That’s roughly 11 percentage points of fiber digestibility compromised by delayed harvest.

Why does that matter so much? Work from Michigan State—specifically, Drs. Mike Oba and Mike Allen—established that each percentage point of NDF digestibility improvement corresponds to about 0.40 pounds more daily dry matter intake and 0.55 pounds more 4% fat-corrected milk. When you’re losing 11 points of digestibility, the math gets uncomfortable quickly.

The challenge is practical. Corn typically dries at 0.5-0.75% per day during fall conditions (though weather obviously affects this). An operation with 10 days of chopping capacity that waits for an ideal 35% dry matter may finish well above 40%.

For a 300-cow dairy feeding late-harvest silage, the consequences compound:

- Additional corn grain needed to replace lost energy: roughly $17,500 annually

- Higher shrink losses from compromised packing and aerobic stability: approximately $15,000 annually

- Unrecoverable milk from reduced intake: around $19,700 annually

That’s more than $52,000 in annual impact from decisions made in a few autumn days. This is one area where even experienced operations sometimes get caught by weather or competing priorities.

When Caution Is Warranted

Any honest discussion of these strategies must acknowledge situations in which aggressive implementation can backfire.

- Variable forage quality presents real challenges. Operations dealing with inconsistent harvest conditions, limited storage infrastructure, or purchased feeds with uncertain history face genuine risk when tightening protein margins. The traditional safety cushion exists for good reason.

- Existing rumen health issues complicate the picture. Herds already managing subclinical acidosis have compromised rumen function. Reducing protein on top of SARA often makes things worse. Address rumen health first.

- Monitoring limitations matter. Operations relying primarily on bulk tank MUN and monthly DHI tests may not detect problems quickly enough. More frequent observation—at minimum, close attention to milk protein percentage and manure consistency—becomes essential when operating near the efficiency frontier.

- Regional and system differences affect optimal approaches. Southwest operations managing heat stress face different metabolic pressures than those in the Upper Midwest. Farms built around byproduct feeds have different amino acid profiles than corn silage-alfalfa operations. And for pasture-based systems—whether in Ireland, New Zealand, or parts of Australia—these TMR-focused strategies require significant adaptation for grazing contexts where lush pasture protein creates entirely different management challenges.

And some nutritionists raise reasonable questions about whether current amino acid models are precise enough to support aggressive protein reduction across all scenarios. “The science is clearly trending this direction,” one told me, “but I’m not convinced we have the precision yet for every situation.” That perspective deserves respect.

How the Strategies Work Together

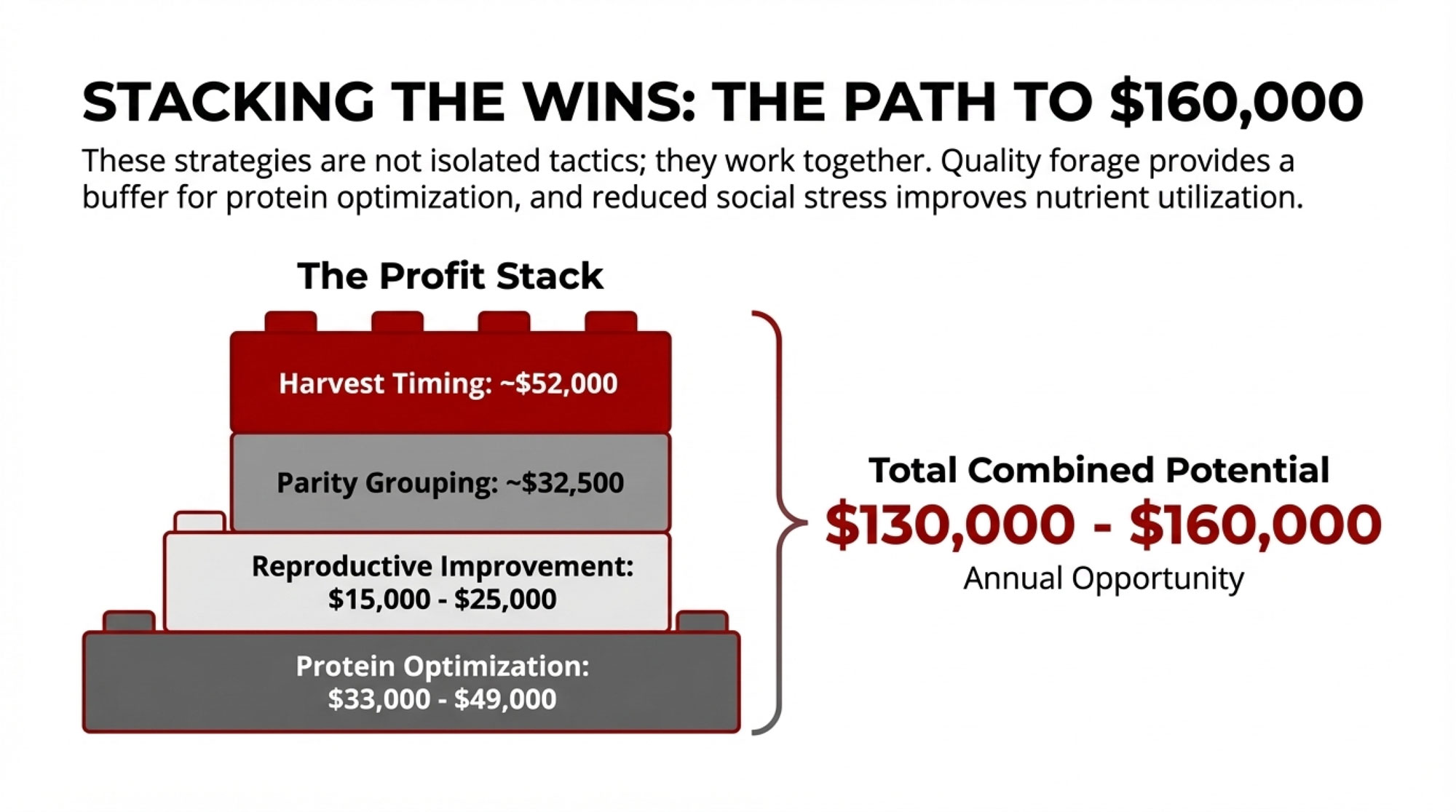

What makes these approaches compelling is how they interact. Operations implementing multiple strategies often see returns exceeding the simple sum of individual improvements.

| Strategy | Per Cow Annual Value ($) | 300-Cow Herd Impact ($) |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Optimization | $110-165 | $33,000-49,000 |

| Reproductive Improvement (Lower MUN) | $50-85 | $15,000-25,000 |

| Parity Grouping (Zero-Cost) | $108 | $32,500 |

| Optimal Harvest Timing | $174 | $52,000 |

| Total Annual Opportunity | $442-532 | $130,000-$160,000 |

Quality forage creates a safety margin for lower-protein diets—rumen microbes need readily available energy to utilize limited nitrogen efficiently. Reduced social stress from proper grouping improves nutrient utilization. Better body condition from appropriate MUN levels supports reproduction, gradually improving herd structure over time.

Here’s how the numbers add up when you put these pieces together for a 300-cow operation:

| Strategy | Est. Annual Value (Per Cow) | Primary Driver |

| Protein Optimization | $110-165 | Reduced nitrogen waste & feed cost |

| Reproductive Improvement | $50-85 | Lower MUN / higher pregnancy rates |

| Parity Grouping | $108 | Reduced social stress in heifers |

| Harvest Timing | $174 | Improved NDF digestibility |

| Combined Potential | $442-532 | Combined management impact |

That suggests an annual improvement potential of $130,000 to $160,000 for a 300-cow dairy. Your specific numbers will shift based on milk price, regional feed costs, current practices, and implementation success—but the general magnitude tends to hold. You can adjust these figures for your own milk price and feed costs to get a better sense of what applies to your operation.

Your 30-Day Quick Start

- Pull DHI MUN records—check variation across your herd

- Separate first-lactation heifers into their own group (zero cost, immediate impact)

- Schedule a nutritionist review for the amino acid balancing feasibility

- Mark the corn silage target harvest date on the calendar now

The Component Pricing Connection

One additional factor worth considering: current component pricing structures can amplify or dampen the returns from these strategies, depending on your market.

In regions where protein premiums remain strong relative to butterfat, the milk protein percentage improvements from proper amino acid balancing deliver direct check impact beyond feed savings. Conversely, in markets where butterfat premiums dominate (as they have in many U.S. Federal Orders through 2024-2025), the reproductive and efficiency gains matter more than component shifts.

The point is that these strategies aren’t one-size-fits-all economically any more than they are nutritionally. Understanding your specific market’s component structure helps prioritize which elements to implement first.

Realistic Expectations for the Timeline

Operations considering this path should understand what a realistic timeline looks like.

| Timeline | What’s Actually Happening | Monthly Cash Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Month 1 | Feed cost reduction appears immediately | +$1,500-$2,000 |

| Months 2-3 | Amino acid costs peak, milk check looks same—patience required | +$500-$1,000 |

| Months 4-6 | Heifer grouping benefits measurable, component premiums visible | +$2,500-$3,500 |

| Month 6+ | New crop forage (optimal harvest) creates largest single cash gain | +$4,500-$6,000 |

| Months 12-18 | Full reproductive cycle improvement compounds into herd demographics | +$10,000-$13,000 |

What’s Coming Next

Looking ahead, several developments may make precision protein feeding more accessible and reliable.

Real-time MUN monitoring through inline milk analyzers is becoming more practical, potentially allowing daily or even milking-by-milking adjustments rather than waiting for monthly DHI results. Precision feeding systems that deliver individualized rations based on production stage, body condition, and metabolic status are moving from research herds to commercial application. And genomic selection for feed efficiency traits—still in early stages—may eventually allow producers to select animals that convert feed more efficiently at the genetic level.

These technologies won’t replace good nutritional management, but they may provide better tools for finding and maintaining optimal protein levels for individual animals rather than group averages. Worth watching as these systems mature.

Practical Guidance by Operation Size

- For herds with fewer than 100 cows, the management complexity of multi-group feeding may not justify the labor investment. Focus on forage quality and gradual protein optimization first. The diagnostic approach still applies—just proceed more slowly and acknowledge real constraints on management time.

- For herds of 120-300 cows: The economic case for fresh cow differentiation and heifer separation becomes quite compelling. Consider starting with parity grouping (requiring no ration changes) to build confidence in nutritional optimization. This range represents something of a sweet spot for these strategies.

- For herds with more than 300 cows, full implementation represents a substantial annual opportunity. The 18-month timeline means changes initiated now affect profitability through 2027 and beyond. At this scale, the question shifts from “whether” to “how well and how quickly.”

- For all operations: Perhaps the most common mistake is confusing high feed efficiency numbers with genuinely profitable efficiency. A cow showing 1.8 pounds of milk per pound of dry matter intake while losing body condition isn’t efficient—she’s depleting reserves that will be repaid through reproductive failure, health challenges, or premature culling. Sustainable efficiency means strong production supported by adequate intake and stable body condition.

Your Next 3 Moves

- Review the last 6 months of DHI MUN data—calculate your herd’s variation and identify outliers

- Walk your fresh pen and first-lactation group this week—observe feeding behavior during and after TMR delivery

- Block 30 minutes with your nutritionist—discuss amino acid balancing feasibility for your specific forage base

The Bottom Line

The opportunity exists for many operations. Whether to pursue it—and how aggressively—depends on management capacity, forage infrastructure, current practices, and appropriate risk tolerance. But the underlying economics, for those positioned to capture them, continue to look favorable.

Key Takeaways:

- Cut 2% protein, bank $40,000: Balanced 15-16.5% CP diets match 17-18% production—saving $33,000-$49,000/year on a 300-cow herd

- Fix MUN, fix fertility: Every 1 mg/dL above 14 costs ~10% conception odds. Target 10-14 mg/dL for $15,000-$25,000 in annual reproductive savings

- Separate heifers today—it costs nothing: First-lactation cows in their own pen gain 506 lbs/lactation. That’s $32,500/year at zero feed cost

- Miss harvest timing, lose $52,000: Late-chopped silage drops NDF digestibility 11 points. That milk loss can’t be bought back

- Stack all four for $130K-$160K/year: But first—pull MUN records. Variation over ±4 mg/dL means TMR problems to fix before touching protein

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Feed Smart: Cutting Costs Without Compromising Cows in 2025 – Arms you with a tactical roadmap to capture $470 per cow in annual savings. It breaks down corn procurement strategies and forage NDF optimization, turning market volatility into a decisive feed cost advantage for the 2025 season.

- Stop Tightening Your Belt: Dairy’s $6.35/cwt Gap and Your 90-Day Window to Close It – Exposes the structural shifts hitting the industry in 2026, delivering a 90-day blueprint to close the $6.35 per hundredweightmargin gap. It reveals how to move beyond passive belt-tightening into aggressive capital allocation and proactive risk management.

- Research Shows How to Slash Nitrate Leaching by 28% While Boosting Milk Protein. – Reveals a genetic breakthrough in breeding for low-MUNBV cows to slash nitrate leaching by 28%. It delivers a path to securing premium processor payments while simultaneously boosting milk protein percentages without making a single ration change.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!