Your dairy loses $13,400/month after a hurricane. Government aid takes 12 months. Do you have 6 months reserves? Because 30 days isn’t enough anymore.

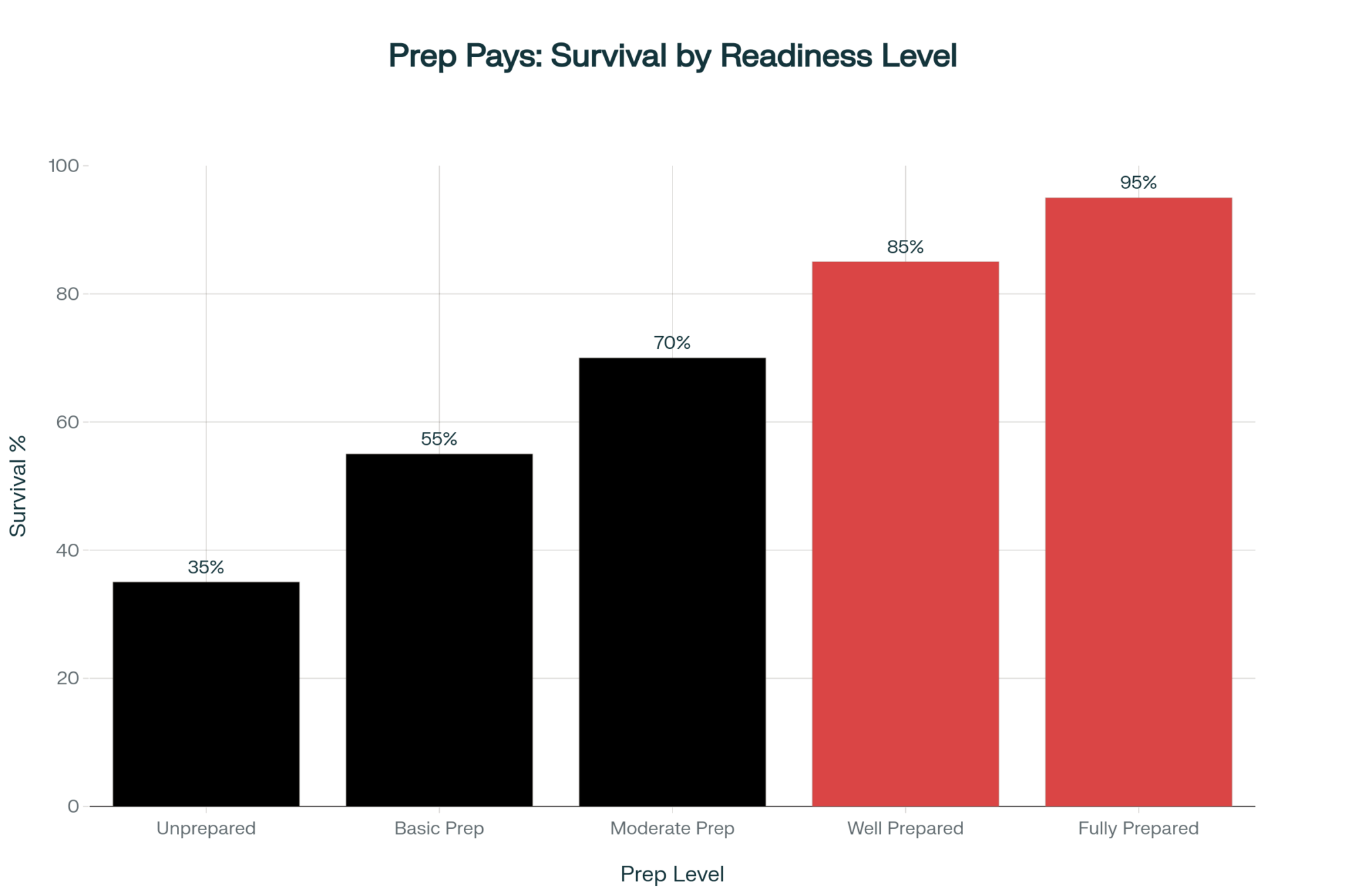

Executive Summary: Four hurricanes in 13 months taught Florida dairy farmers what $500,000 buys: survival. The farms still standing had six months of cash reserves and could afford solar backup, hurricane-proof construction, and layered insurance—everyone else is bleeding $13,400 monthly or already gone. This exposed a brutal truth: mid-size family dairies can’t afford climate resilience but can’t compete without it. They face three stark options: scale up past 1,000 cows, find premium niche markets, or exit while there’s still equity to preserve. The math is unforgiving—strategic exit at month 8 saves families $380,000-$580,000 compared to forced liquidation at month 18. With government aid covering just 22% of losses and mutual aid networks exhausted, Florida’s experience reveals the future of farming: only operations with capital access survive repeated climate disasters.

You know that feeling when you walk through your barn after a storm and everything’s different? Jerry Dakin had that moment last year, standing in his Myakka City dairy farm looking at 250 dead cows scattered across his pastures after Hurricane Ian hit in September 2022. He’d spent decades building Dakin Dairy up to 3,100 head—good genetics, solid facilities, everything running like it should.

Here’s what nobody saw coming, though. Ian was just the start. We had Idalia, then Debby, then Helene, and finally Milton—all hitting through October 2024. Suddenly, resilience wasn’t just something we talked about over coffee at the co-op. It became what decided who’d still be milking come next season.

What’s really interesting—and this caught my attention when the November data came out from USDA—is that the Southeast actually lost fewer dairy herds than anywhere else in the country during all this. We’re talking 100 farms, compared to over 200 in other regions, according to Progressive Dairy. So what made the difference? The strategies that worked tell a story we all need to hear.

“The difference between making a strategic decision at month 8-10 versus being forced out at month 18? We’re talking $380,000 to $580,000 in what the family keeps.”

The Real Timeline of Financial Recovery (It’s Not What You Think)

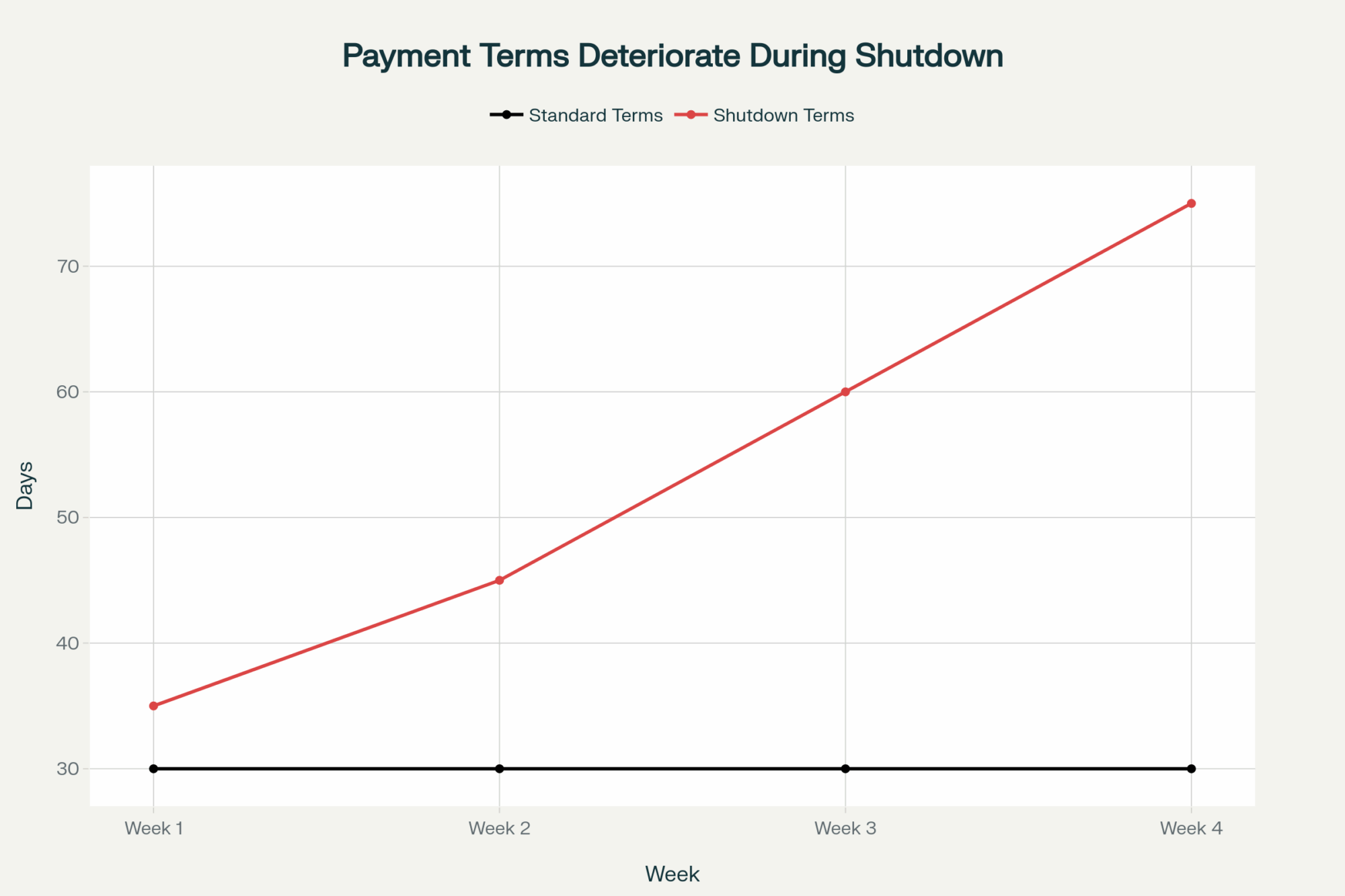

You know how we usually handle disasters? Fix what’s broken, get the power back on, clean up the mess, and move forward. But what I’ve learned talking to farmers who’ve been through this is that the real challenge isn’t the hurricane. It’s what happens to your cash flow over the next 18 months.

Take Philip Watts at Full Circle Dairy near Mayo. Hurricane Helene knocked down three-quarters of their free-stall barn and damaged 12 of their 16 pivots. Bad enough, right? But here’s what really hurt—their production dropped 10-15% and just stayed there for months. The Florida Department of Agriculture documented this in their October assessments. Average dairy was losing $13,400 a month in operational costs while waiting for help that… well, it takes time.

What I’ve found is there’s a pattern here that we need to understand…

The Numbers We Need to Talk About:

So government assistance—and I’m not pointing fingers, just stating facts—covered about 22% of actual losses. Commissioner Simpson announced those block grants in July 2025, totaling $675.9 million. Sounds like a lot until you realize the damage from four hurricanes topped $3 billion.

Meanwhile, working capital’s bleeding out at $13,400 a month for a mid-size operation. That’s based on what United Dairy Farmers of Florida found in a survey of its members early in 2024. Real money, real fast.

And here’s something agricultural economists have figured out—the difference between making a strategic decision at month 8-10 versus being forced out at month 18? We’re talking $380,000 to $580,000 in what the family keeps. That’s college funds, retirement, the next generation’s chance to start over.

Johan Heijkoop put it pretty bluntly after Idalia hit his two Lafayette County farms: “We don’t have a year to get help from this. We need action. We need it immediately.” A month after that storm, he still had eight burn piles going. His cows? Still way off their normal production.

Financial analysis backs this up—operations with minimal reserves face insolvency within 12-18 months after major disasters. The farms with 6-12 months of operating reserves? They made it. Those running on the traditional 30-60-day cushion —we’ve always thought was fine? Different story.

What’s Actually Working Out There (Real Farms, Real Solutions)

Let me share what farmers are actually doing—not what some manual says they should do, but what’s happening on real operations right now.

Getting Off the Grid (At Least Partially)

Here’s something that got everyone talking. Duke Energy’s Lake Placid solar farm took a direct hit from an EF2 tornado during Hurricane Milton. Four days later, it’s back online. Four days! That changed how a lot of us think about solar.

What’s encouraging is that farms are putting together complete systems now. We’re seeing 50-100kW solar arrays handling daytime loads—critical for cooling in Florida’s heat. Battery storage in the 100-200kWh range keeps the parlor running at night, keeps those bulk tanks cold. And yeah, you still need standby generators with at least 2 weeks of fuel. USDA’s hurricane guide got that part right.

The investment? You’re looking at $150,000 to $200,000 for a mid-size place. I know, I know—that’s serious money. But REAP program data shows you’re getting that back in 6-8 years just on electricity savings. And when the next storm knocks the grid out for a week? Priceless.

Building Different (Because We Have To)

The Watts family—they zip-tied 900 fans before Helene hit. That’s dedication. But when they rebuilt that barn, they did it right.

Florida’s 2023 building code—the 8th edition for those keeping track—changed the game. We’re talking 140+ mph wind ratings now. Hurricane clips on every truss. Electrical panels must be at least 3 feet above flood stage. And those pivots? Quick-disconnects that cut removal time from two hours to maybe 20 minutes.

Some of my friends up in Wisconsin think this is overkill. Then again, they’re not dealing with Category 4 storms.

Insurance That Actually Works

With Risk Management Agency data showing that 53% of ag damage falls outside traditional coverage, Florida producers got creative. Had to.

Ray Hodge over at United Dairy Farmers walked me through what’s working. You layer it up: Whole Farm Revenue Protection at that new 90% level (used to be 85%). Dairy Margin Coverage at $9.50—it’s triggered payments 57% of the time over the last few years. Hurricane wind index insurance that pays automatically when winds hit certain speeds—no waiting for adjusters. And business interruption coverage for lost income during recovery.

A producer near Okeechobee said it best: “Building $300,000 in diversified revenue protection beats hoping for $25 milk.” Can’t argue with that.

Quick Reference: Insurance Layering Strategy

- Base Layer: Whole Farm Revenue Protection (90% coverage)

- Margin Protection: Dairy Margin Coverage ($9.50/cwt level)

- Catastrophic Coverage: Hurricane Insurance Protection-Wind Index

- Income Protection: Business Interruption Insurance

- Combined Result: Closes most of the 53% coverage gap

When Everyone Needs Help at the Same Time

You probably heard about Willis Martin bringing 40 Mennonite volunteers down from Pennsylvania to rebuild Jerry Dakin’s barns after Ian. One week, they got it done. Over 100 locals showed up too—clearing debris, helping with vet work, keeping those cows milked. Dakin’s café became the community hub. It was something to see.

But by the time Milton hit—that’s the fourth major storm in thirteen months—everybody was exhausted. You could feel it.

How Things Are Changing:

What I’m seeing now is farms getting formal about what used to be handshake deals. Equipment sharing with actual legal agreements. Labor exchanges spelled out—who helps who, when, for how long. Feed purchasing co-ops with locked-in emergency prices so nobody gets gouged when disaster hits. Even evacuation partnerships with farms in Georgia and Alabama, complete with health papers ready to go.

Sara Weldon’s story from her Clermont farm during Milton really stuck with me. She spent three days prepping—brought the donkeys and goats in the house (yeah, in the house), turned the bigger animals loose in back pastures, and stockpiled everything. All her animals made it. But you could hear it in her voice afterward—the exhaustion from going through this again and again.

Florida Farm Bureau’s February 2025 mental health report hit hard: 67% of farmers reporting depression, 9% having suicidal thoughts. These are the people who make mutual aid work, and they’re running on empty.

The Hard Truth About Scale

So here’s where it gets uncomfortable. All these solutions that work—solar systems, hurricane-proof barns, feed reserves, comprehensive insurance—you’re talking about $500,000 upfront for a mid-size dairy. That’s the reality.

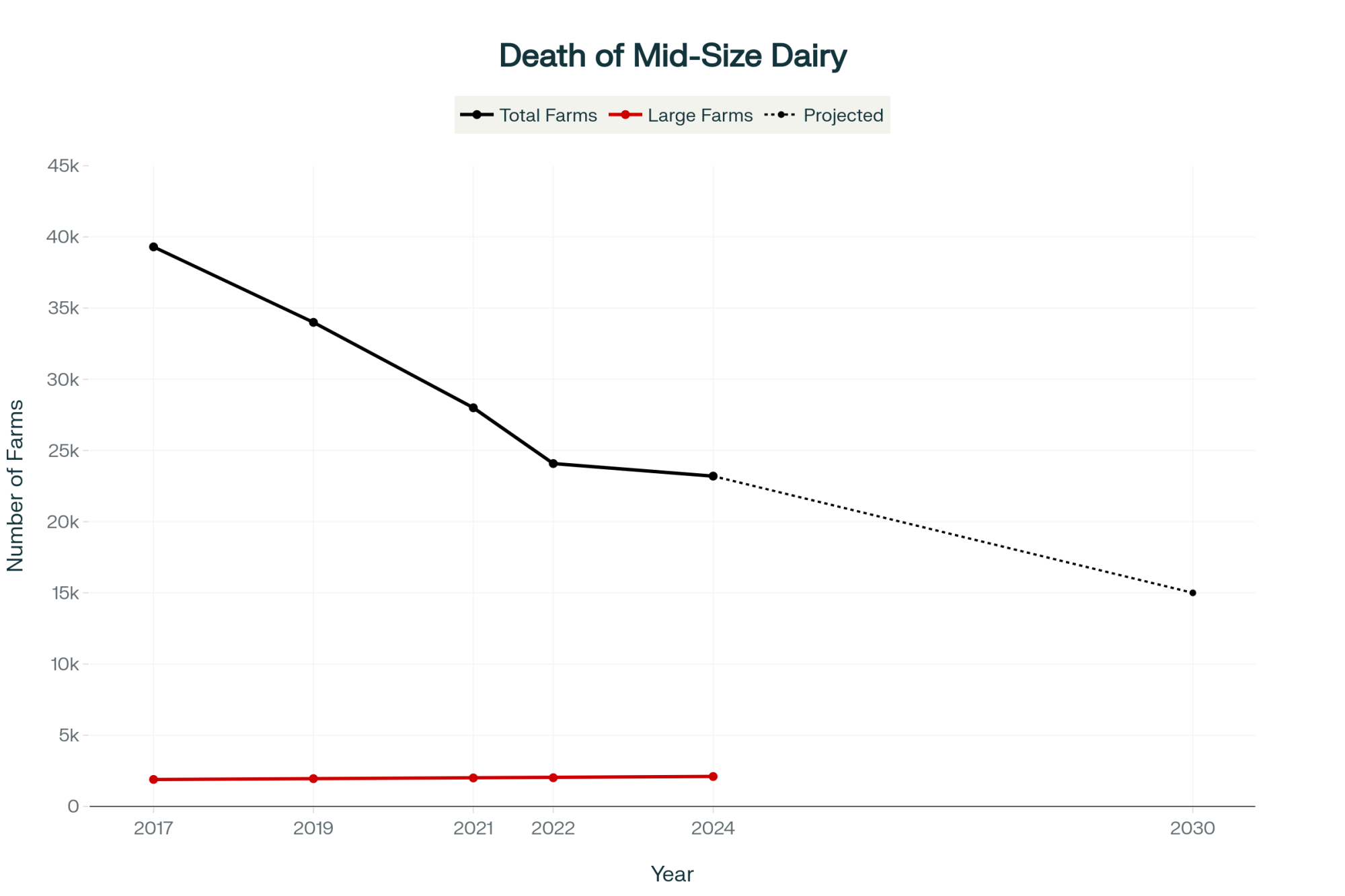

Jerry Dakin with 3,100 cows and $8-10 million in revenue? Plus on-farm processing? He can probably swing it. But that 300-cow family operation grossing $900,000, maybe netting $50,000-$80,000 in a good year? The math doesn’t work, and pretending it does doesn’t help anybody.

Three Ways This Is Playing Out:

Based on what Cornell’s been documenting the last few years, here’s what’s happening:

Getting Bigger (1,000+ cows): When you spread that $500,000 investment over enough production, the per-hundredweight cost becomes manageable. Plus—and we need to be honest here—these are the operations processors want to work with.

Finding Your Niche (<200 cows): Organic’s working for some folks—USDA data confirms those 50-75% premiumsare real. Grass-fed, direct sales, agritourism. But you need the right location. Affluent customers nearby. Rural Okeechobee doesn’t have that market.

Making the Hard Decision: Some are choosing to exit while they still have equity. It’s not giving up—it’s protecting what the family’s built over generations.

What doesn’t work? Trying to stay mid-size without access to capital. We lost 1,420 dairy farms in 2024—about 5% of what’s left. At this rate, projections suggest we’ll be down to 12,000 operations by 2035. That’s a conversation we need to have.

What’s interesting here is how this mirrors what’s happening in Texas coastal dairy regions. After Hurricane Harvey in 2017, they saw similar consolidation patterns—the operations that could afford flood mitigation survived, the rest didn’t. It’s not just a Florida story anymore.

The Part Nobody Talks About

Behind every spreadsheet, a farmer is asking themselves: “If I’m not doing this, who am I?”

Dr. Rebecca Purc-Stephenson, up at the University of Alberta, studies this stuff. She explained it to me once—farming isn’t a job, it’s your whole life. Your identity. Hard to separate who you are from what you do.

For families that have been farming for generations—and that’s most of Florida dairy—it’s even harder. Your grandfather made it through the Depression. Your dad survived the ’80s farm crisis. Now you might be the one who has to walk away because of hurricanes? Even when it’s not your fault, that leaves marks.

One Florida farmer—he asked me not to use his name—described the stages. First, you deny it’s that bad. Then you’re confused when routines disappear. Angry at banks, government, anybody who can’t help fast enough. Guilty about what you should’ve done different. And sometimes, depression that gets dangerous.

“When those cows are gone and everything stops,” he said, “it feels like someone in the family died.” But asking for help? That goes against everything we’ve been taught about being self-reliant. It’s a trap where the folks who need help most are least likely to ask for it.

What the Rest of Us Can Learn

After spending time with these Florida farmers, three big lessons stand out:

First: Financial Resilience Is Everything

Build 6-12 months of operating capital. I know that’s way more than the 30-60 days we’ve always managed on, but it matters. Layer your insurance to close gaps—and actually read those policies. Set up credit lines with disaster triggers before you need them. And decide your exit criteria now, while you’re thinking clearly.

Second: Formalize Your Networks Before Crisis

Get agreements in writing—handshakes don’t hold up under this kind of stress. Fund coordinator positions to prevent volunteers from burning out. Build relationships with farms in different climate zones. And integrate mental health support before people need it—because by then, it’s often too late.

Third: Accept That Some Things Can’t Be Fixed

Sometimes a region’s climate changes beyond what certain types of farming can handle. Better to choose proactively between scaling up, finding a niche, or transitioning than to have the market force it on you. Push for policies that help all farm sizes, not just the biggest. And consider that a managed transition might beat chaotic collapse.

Where We Go from Here

What Florida dairy farmers learned the hard way is that climate patterns are changing faster than we can adapt to them. Four hurricanes in thirteen months isn’t bad luck—NOAA’s 2024 reports make it clear this is the new pattern.

The farms surviving aren’t always the best managed or the ones with the strongest communities—though both matter. More and more, they’re the ones with capital access and enough scale to justify big infrastructure investments. That’s accelerating consolidation, whether we like it or not.

But here’s what gives me hope: Florida farmers have innovated like crazy. Solar systems that keep operations running when the grid fails. Formal mutual aid replacing informal arrangements. Risk management strategies that actually work. These are blueprints other regions can use.

Commissioner Simpson got it right, talking to the Cattlemen’s Association: “Food production is not just an economic issue, it’s a matter of national security.” The question is: will we learn from Florida’s experience, or wait for our own disasters to teach us the same lessons?

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re farming today: Check your working capital. Less than six months? Building reserves beats any expansion plan. Review every insurance policy for gaps—especially business interruption and parametric products. Get your mutual aid relationships on paper. Define your triggers: What would make you exit? What would force it?

Planning ahead: Figure out if your operation size sets you up for long-term success. Look at cooperative approaches to share infrastructure costs. Build relationships outside your climate zone. And consider revenue beyond just milk—diversification is adaptation, not defeat.

Long-term thinking: Accept that some regions might not support certain farming anymore. Understand that resilience might mean transition, not staying put forever. Know that climate adaptation favors bigger, better-funded operations. Plan for weather volatility as the new normal.

Florida’s dairy farmers deserve more than just credit for resilience. Through incredible hardship, they’ve given the rest of us a real education in what climate adaptation actually costs—in dollars and in human terms.

We can learn from what they’ve been through, or we can learn it the hard way ourselves. Unlike the weather, at least that choice is still ours to make.

Key Takeaways:

- Your survival number is 6-12 months reserves, not 30-60 days: Florida farms with deep reserves weathered $13,400 monthly losses for 18 months. Everyone else is gone.

- Climate resilience costs $500K (solar, construction, insurance): Operations that can’t afford it have three options—scale up past 1,000 cows, find premium niches under 200 cows, or exit now.

- The $380,000 decision window: Exit strategically at month 8-10 and preserve family wealth, or watch it evaporate by month 18 in forced liquidation.

- Mutual aid has limits—formalize before you need it: After four hurricanes, volunteer networks are exhausted, and 67% of farmers report depression. Written agreements and funded coordinators beat handshakes.

- Florida’s present is agriculture’s future: Every region facing climate intensification will see this same pattern—only capitalized operations survive repeated disasters.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Why All Dairy Farmers Need a Risk Management Plan – This article details the crucial first steps for building a comprehensive plan. It provides strategies for identifying financial and operational vulnerabilities before a disaster, complementing the main article’s focus on recovery.

- Navigating the Future: Key Strategies for Dairy Farm Succession Planning – While the main article outlines the “exit” option, this piece provides the how. It details strategies for succession and transition, ensuring you protect the family equity and legacy that disasters threaten.

- Robotic Milking Systems: Are They the Key to a More Resilient Dairy Industry? – This analysis explores resilience from a different angle: labor. It demonstrates how automation secures milking operations when storms exhaust mutual aid networks and make hired labor impossible to find.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!![Generate comprehensive SEO elements for this The Bullvine article targeting dairy industry professionals seeking practical, ROI-focused solutions.

ANALYSIS REQUIREMENTS:

Identify the article's primary topic and specific target audience (dairy producers, agricultural specialists, farm managers, genetics specialists)

Focus on practical, implementation-oriented keywords that dairy professionals would search for

Prioritize terms connecting to profitability, efficiency gains, and competitive advantages

Consider both technical dairy terminology and business/economic terms

SEO DELIVERABLES:

1. SEO KEYWORDS (7 High-Impact Keywords):

Create a comma-separated list mixing:

* 2-3 Primary Dairy Terms (dairy farming, milk production, herd management, genetics, nutrition)

* 2-3 Business/ROI Terms (dairy profitability, farm efficiency, cost reduction, profit margins, operational optimization)

* 1-2 Technology/Innovation Terms when applicable (precision agriculture, automated milking, genomic testing, robotic milking)

* 1 Geographic/Market Term if relevant (North American dairy, global dairy trends, regional market analysis)

1. FOCUS KEYPHRASE (2-4 Words):

Develop a primary keyphrase that captures the article's core topic and would be commonly searched by dairy professionals seeking this information. Must have strong commercial intent and natural integration potential.

2. META DESCRIPTION (150-160 Characters):

Write a compelling meta description that:

* Opens with compelling benefit or surprising statistic

* Naturally incorporates the focus keyphrase in first 80 characters

* Clearly communicates specific outcome (cost savings, efficiency gains, profit increases)

* Uses action-oriented language ("Discover," "Boost," "Maximize," "Transform")

* Appeals to industry decision-makers and technical specialists

* Includes 2025 market context when appropriate

1. RECOMMENDED TITLE (50-60 Characters):

Create an optimized title incorporating focus keyphrase and clear value proposition for maximum click-through rate.

2. CATEGORY RECOMMENDATIONS:

Suggest PRIMARY and SECONDARY categories from The Bullvine options:

Primary Categories: Dairy Industry, Genetics, Management, Technology, A.I. Industry, Dairy Markets, Nutrition, Robotic Milking

Consider cross-category opportunities for maximum internal linking

OUTPUT FORMAT:

text

SEO KEYWORDS: [7 keywords separated by commas]

FOCUS KEYPHRASE: [2-4 word primary keyphrase]

META DESCRIPTION: [150-160 character description with keyphrase and value proposition]

PRIMARY CATEGORY: [main category from The Bullvine options]

SECONDARY CATEGORY: [additional relevant category]

DAIRY INDUSTRY CONTEXT:

Target progressive dairy producers seeking ROI-focused solutions, agricultural specialists, farm managers, and industry consultants. Ensure all elements support practical implementation guidance, competitive intelligence, and risk management strategies. Focus on commercial intent keywords indicating purchase/implementation readiness while maintaining The Bullvine's authoritative position in dairy industry professional content.](https://www.thebullvine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Google_AI_Studio_2025-10-04T16_55_02.422Z.png)