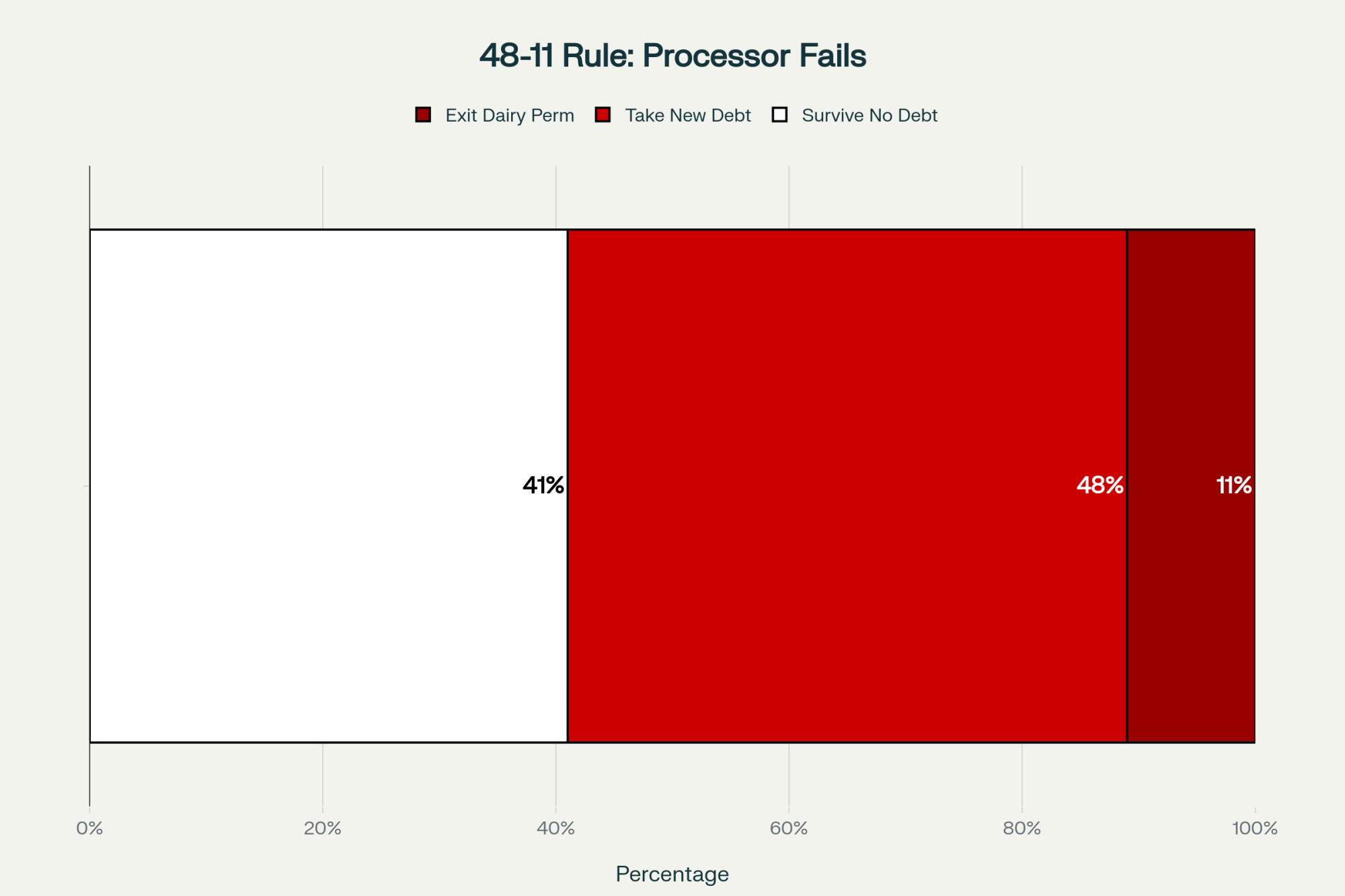

48% of farms take on debt when processors fail. 11% never recover. The difference? Three months of cash no bank can freeze

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Your processor could fail tomorrow—93 French dairy farms just learned this the hard way in October 2025. With 73% of regional dairy processors lost since 2000, today’s consolidated market has transformed processor failure from a minor inconvenience to an existential threat. When it happens, you have exactly 72 hours before bulk tank capacity forces you to dump milk, and nearly half of affected farms will take on debt, while 11% won’t survive at all. Yet farmers who’ve built what we call a “financial firewall”—90 days of accessible reserves (about $280,000 for a 200-cow operation), pre-established processor relationships, and specialized insurance—are actually thriving during these crises, with some negotiating better contracts than before. This comprehensive guide provides your complete risk management playbook: practical strategies to build reserves even on tight margins, early warning signs to watch for, contract clauses that protect you, and the collaborative approaches that multiply individual farmer power. The difference between farms that fail and farms that thrive isn’t luck—it’s preparation.

The recent Chavegrand situation in France offers important lessons about processor risk management. Here’s what progressive dairy operations are learning about financial preparedness in an era of consolidation.

Let me share a scenario that’s becoming more common than any of us would like. You’re running a solid operation—maybe 200 milking cows, your SCC consistently under 200,000, butterfat levels holding steady at 3.8 to 4.0. Everything on your end is working like it should. Then the phone rings with news that changes everything: your processor just suspended milk collection.

This exact situation hit 93 dairy farms in France’s Creuse region this October. Their processor, Chavegrand, shut down operations after a contamination incident that French health authorities connected to consumer illnesses and deaths. What really catches my attention here—based on the regional farm media coverage—is that these weren’t struggling operations. We’re talking about established, multi-generational farms, the kind that follow protocols and maintain quality standards year after year.

“We’re passengers, not drivers. And consolidation has made that ride a lot riskier than it used to be.”

You know, this whole thing really shows us something we’ve all been dealing with. We can control so much—our breeding programs, our feed quality, fresh cow management, all the production variables we’ve mastered over the years. But when it comes to our processor’s business decisions? That’s where we’re passengers, not drivers. And consolidation has made that ride a lot riskier than it used to be.

That Critical First 72 Hours

Here’s what’s interesting about processor failures—and I’ve been talking with extension folks from Wisconsin and Cornell who’ve been documenting this pattern. When your processor stops picking up milk, you’ve basically got 72 hours before you’re facing some really tough decisions. That’s just the reality of bulk tank capacity on most farms.

The first couple of days, you’re usually okay. Your tank’s filling while you’re working the phone, calling every processor within a reasonable distance. But day three? That’s when things get complicated. Feed deliveries keep coming. Your team needs their paychecks. The bank’s expecting that loan payment. Meanwhile, that milk check you were counting on to cover all this… well, it’s not coming.

I’ve been hearing similar stories from farmers who’ve lived through processor transitions. One Vermont producer I talked with had built up about three months of operating reserves—roughly what it would take for a 150-cow herd, maybe $180,000 or so. “Yeah, it wasn’t easy having that cash sitting in savings earning next to nothing,” he told me. “But when our processor went under, I could take my time finding the right deal instead of jumping at whatever was offered.”

His neighbor—a good farmer, who had been at it for years—didn’t have that cushion. Operating paycheck to paycheck, like many of us do, he had to take what he could get. Ended up being about 30 cents less per hundredweight than what the prepared farmer negotiated. Do the math on that over a year’s production… it’s significant money.

Now I know what you’re thinking—where exactly am I supposed to find that kind of cash to park in savings when we’re already watching every penny? Good point. But what I’ve found is that farmers are getting creative about this. Some are running equipment a year or two longer than planned, banking what they would’ve spent on payments. Others—especially in states where it’s allowed—are developing small direct-sales channels. Not to replace bulk sales, but maybe selling 5% of production at premium prices to build reserves faster.

How the Processing Landscape Has Shifted

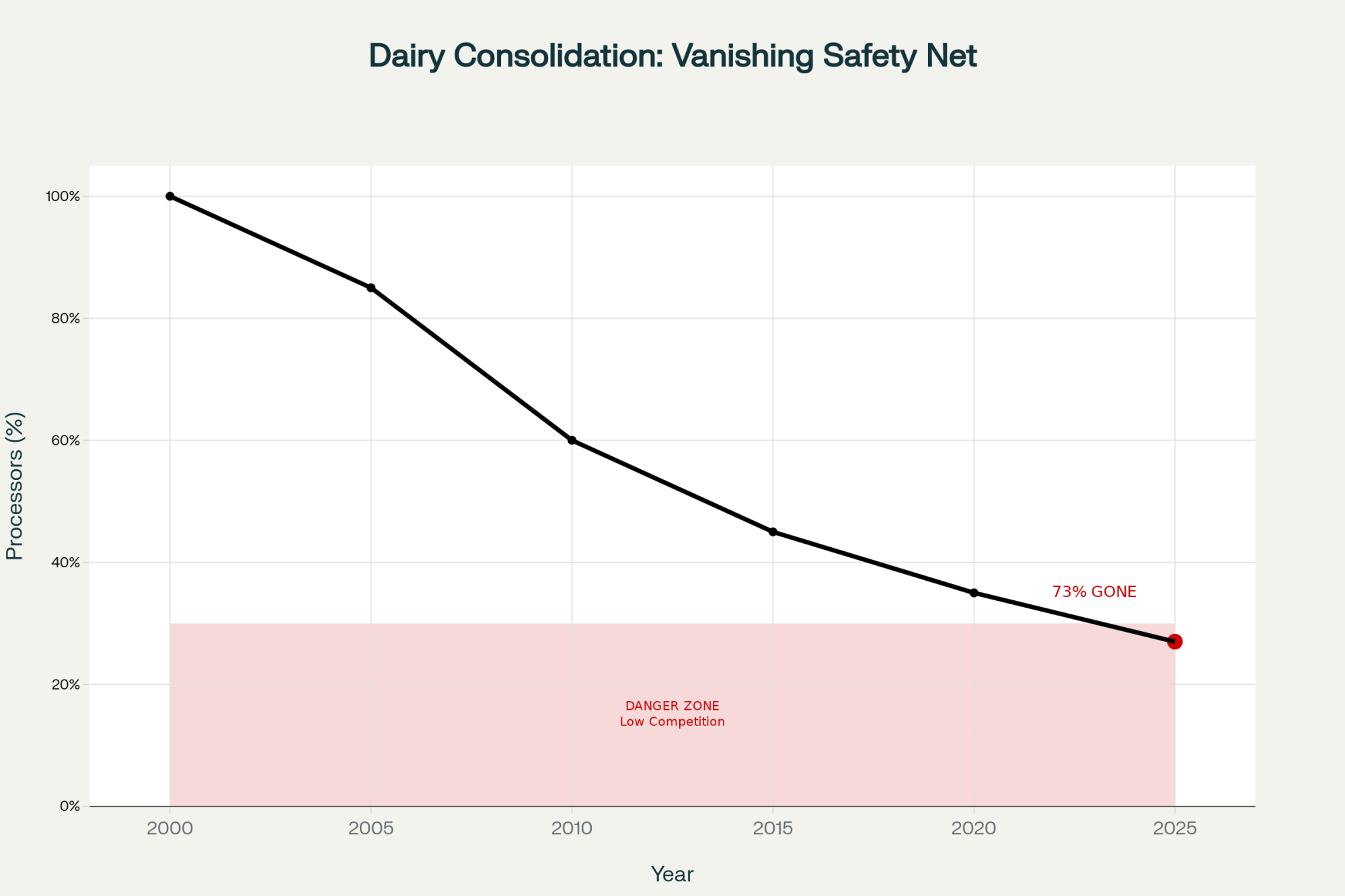

You probably already know this, but it’s worth laying out the numbers. The USDA’s been tracking this, and Rabobank’s latest dairy quarterly from Q3 this year confirms it: we’ve lost somewhere between 65 and 73 percent of our regional processing options since 2000. Where farms used to have 15 or 20 potential buyers within hauling distance, many areas now have three or four real alternatives. And that’s if you’re lucky.

“Between 36 and 48 percent of affected farms end up taking on new debt just to survive the transition.”

Of course, this varies considerably by region—producers in areas with strong cooperatives or supply management systems face different dynamics than those in purely market-driven regions. Canadian producers under their supply management system, for instance, have guaranteed collection through provincial boards even when individual processors fail. Australian dairy farmers working through their cooperative structures have different risk profiles than independent U.S. producers.

Looking at what’s happening in Europe, organizations like FrieslandCampina and Arla have built systems that give farmers greater protection through cooperative ownership. Not saying that model works everywhere, but it’s interesting to see how different market structures create different risk profiles.

I was talking with a producer from upstate New York recently—she’s running about 400 cows. The way she put it really stuck with me: “When I started, we had choices. Now we work with what’s available.”

This creates what the economists call an unbalanced relationship. We need daily pickup—there’s no flexibility there. But processors? They’re drawing from dozens, sometimes hundreds of farms. If they lose one supplier, it’s manageable. If we lose our processor, that could be the end of the operation.

The data released by USDA’s Economic Research Service in its September 2024 Dairy Outlook, along with what the National Milk Producers Federation has documented in its post-bankruptcy analyses, paint a pretty clear picture. When processors fail, between 36 and 48 percent of affected farms take on new debt just to survive the transition. And about one in ten—sometimes a bit more—doesn’t make it. They exit dairy within 1.5 to 2 years. Those aren’t odds I’d want to face without preparation.

Building Your Financial Safety Net

So what can we actually do about this? After talking with farmers who’ve successfully navigated processor transitions—and some who’ve been through it multiple times—I’m seeing patterns in what works.

Getting Liquid Stays Crucial

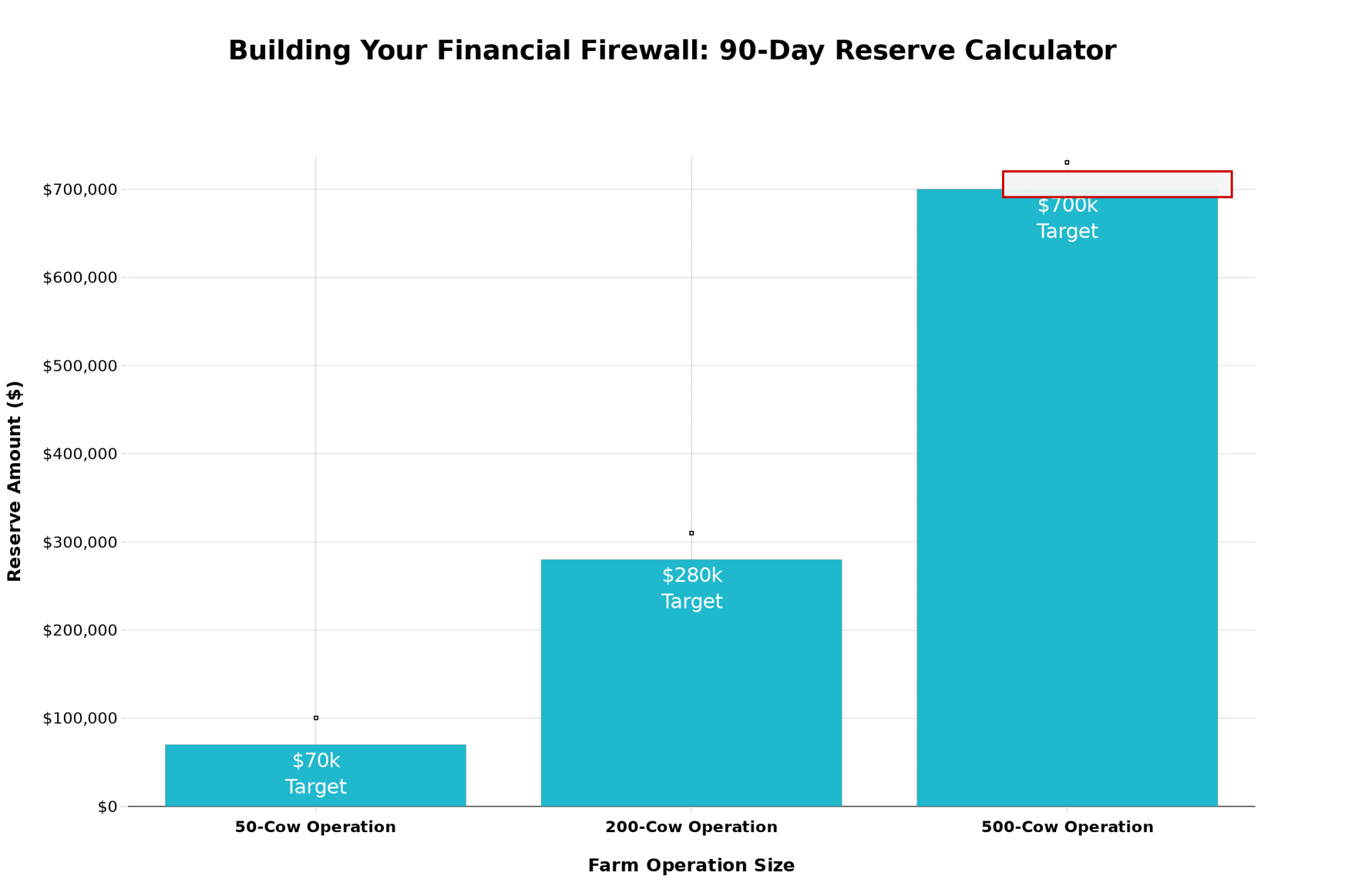

The guidance from university extension programs across the Midwest—Wisconsin’s Center for Dairy Profitability, Minnesota’s dairy team, Michigan State’s ag economics folks—is pretty consistent these days: aim for 90 days of accessible operating capital. And when I say accessible, I mean actual money you can get to immediately—not a credit line the bank might freeze when things look uncertain.

“Aim for 90 days of accessible operating capital.”

For a typical 200-cow Wisconsin operation with weekly expenses around $22,000, you’re looking at building toward roughly $280,000 eventually. I realize that sounds overwhelming. But here’s the perspective that changed my thinking: when Dean Foods went under back in 2019, the National Milk Producers Federation documented that farms without reserves lost well over $100,000 in just the first 60 days. Suddenly, that opportunity cost of keeping cash in low-yield accounts doesn’t look so bad.

But let me share something encouraging, too. I know of a central Pennsylvania farm—about 180 cows—that started building reserves after watching neighbors struggle during a processor closure. They set aside just $500 a month initially, gradually increasing as they could. When their processor ran into financial trouble, they had enough cushion to negotiate properly. Ended up actually improving their contract terms because they weren’t desperate. The tools and strategies exist—it’s really just a matter of implementing them before we need them.

Building Relationships Before You Need Them

I’ve seen some California producers do something really smart. They maintain what amounts to a market awareness system—basically keeping tabs on every potential buyer in their region. Who’s got capacity, what they typically pay, quality requirements, payment terms, all of it.

One of these farmers told me how this paid off when his processor cut intake by 20% with barely any notice: “While everyone else was making cold calls to strangers, I was calling people who already knew our operation. Made all the difference in the world.”

This works differently depending on where you farm, naturally. If you’re near a state line, definitely look across the border. Sometimes those Pennsylvania plants pay better than New York ones, even after factoring in the extra hauling. In areas with strong co-ops, understanding potential merger scenarios becomes important. And as we head into winter feeding season with tighter margins, having these relationships already established becomes even more critical.

Getting Smarter with Contracts

Look, we all know individual farmers don’t have much negotiating leverage. Let’s be honest about that. But what I’m hearing from agricultural attorneys who work with dairy contracts—and this aligns with what Penn State’s ag law program and Wisconsin’s dairy contract resources have been recommending—is that you can sometimes get protective language added even when you can’t move the price.

Instead of beating your head against the wall for another 20 cents per hundredweight, try pushing for something like: “Producer may seek alternative buyers without penalty if Processor suspends collection exceeding 72 consecutive hours for reasons unrelated to milk quality.”

Most processors don’t really care about adding this kind of language because they figure it’ll never matter. But if things go sideways, that clause could save your operation.

Recognizing the Warning Signs

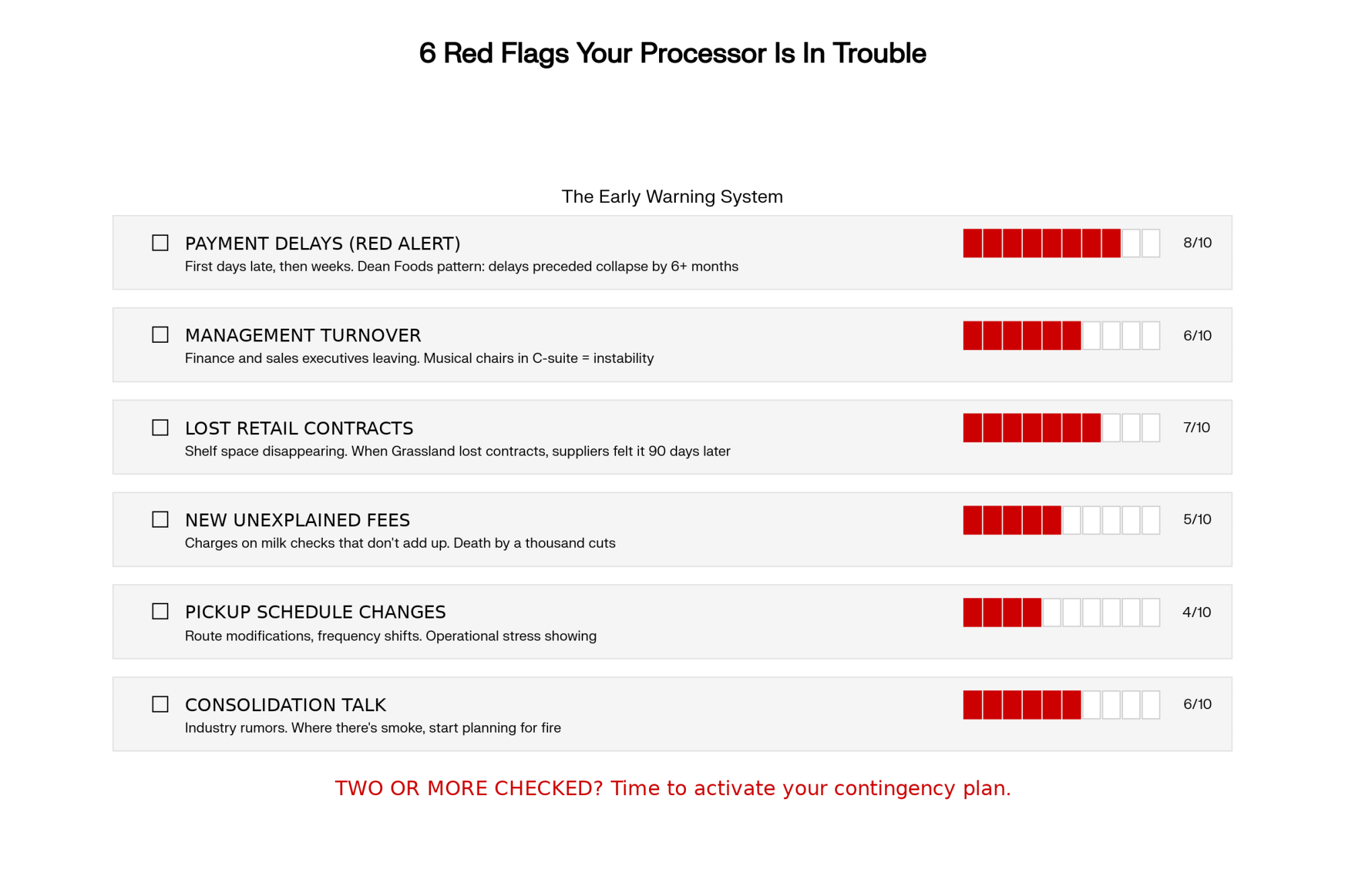

Looking back at processor failures—and researchers at Michigan State and Cornell have documented quite a few in their recent dairy industry reports—the warning signs were almost always there months in advance.

Payment timing is your biggest red flag. When Grassland Dairy restructured its supplier base back in 2017, affected producers told Wisconsin Public Radio that payments had been progressively delayed. First, just a few days, then a week, then requests to “defer” portions.

But there are other indicators too. Management turnover, especially in finance and sales. Lost retail shelf space. New “fees” appearing on milk checks that don’t quite make sense. Unexplained changes to pickup schedules. When you see several of these together, it’s time to dust off those contingency plans.

What’s particularly worth watching is when a processor starts losing major retail contracts or when you hear about consolidation talks. The market’s changing so fast these days that what looks like a stable buyer in January might be in crisis by June.

The Insurance Gap Nobody Talks About

Here’s something that catches a lot of folks off guard: standard farm insurance typically doesn’t cover processor failure or milk buyer bankruptcy. You could have perfect coverage for buildings, equipment, livestock—everything—but if your processor stops picking up milk? That’s usually not covered.

“Farms without reserves lost well over $100,000 in just the first 60 days.”

Specialized coverage is available, though availability varies significantly by state. Business interruption insurance with buyer failure provisions costs about $3,000 to $8,000 annually for mid-sized operations, according to Farm Bureau Financial Services’ current rate guides. Companies like Hartford Steam Boiler, FM Global, and some regional farm mutuals offer these policies, though you’ll find better availability in traditional dairy states like Wisconsin and New York than in newer dairy regions. When you need it, though, it can pay out six figures.

Farm Credit Services has documented several cases in which processors went bankrupt owing farmers $60,000, $70,000, and sometimes more, for multiple weeks of milk. Without accounts receivable insurance, these farmers became unsecured creditors. After legal fees and years of proceedings, they typically recovered less than 20 cents on the dollar. That’s a painful lesson to learn firsthand.

Finding Strength in Numbers

What’s encouraging is seeing producers organize around this challenge. Throughout New England and the Great Lakes states, farmers are forming informal groups to plan for contingencies with processors. Individual farms might ship 15,000 or 20,000 pounds daily—not much leverage there. But get 40 or 50 farms together? Now you’re talking volumes that matter.

These groups also share intelligence. When multiple members spot concerning patterns—such as payment delays, operational changes, or management turnover—everyone can start preparing. It’s the kind of collaboration we need more of.

You know, the Europeans have been doing this for decades through their cooperative structures. The International Dairy Federation’s latest reports show organizations like FrieslandCampina and Arla guarantee milk collection even when individual plants have problems. We’re learning from their model, though our market structure is obviously different.

What You Can Do Starting This Week

If you’re wondering where to begin, here’s what extension specialists from Wisconsin, Cornell, and Penn State are recommending—and it’s pretty practical stuff.

First, figure out your actual daily operating costs. The Farm Financial Standards Council has found that most of us underestimate by 15 to 20 percent, so dig deep. Include everything—feed, labor, utilities, debt service, the whole picture.

Then, honestly assess what cash you could access in 72 hours without selling productive assets. Be realistic here.

Pull out your processor contract. Really read it. What happens if they stop collecting? I’m betting the language heavily favors them.

Over the next month, reach out to other processors in your region. You’re not looking to switch—you’re building relationships, understanding their capacity and needs. Also, review your insurance with specific questions about processor failure coverage and milk buyer bankruptcy protection.

Think about joining or forming a producer group focused on these issues. Set up some system to monitor your processor’s health—payment patterns, industry news, operational changes.

Adapting to Today’s Reality

What those 93 French farms are going through isn’t unique. Industry analysis from Rabobank and the International Dairy Federation shows processor consolidation accelerating everywhere, with the biggest companies now controlling close to 70 percent of global capacity.

I wish I could tell the next generation to just focus on producing quality milk, and everything will work out. Your SCC, butterfat levels, pregnancy rates—all that absolutely still matters. Production excellence remains fundamental.

But in today’s environment, you also need to think about processor stability. Given consolidation trends and the financial pressures in processing that USDA and industry analysts have been documenting, most farms will likely face at least one processor disruption over the next decade. That’s not pessimism—that’s just looking at the patterns.

The good news—and there really is good news here—is that farmers who recognize this shift and prepare accordingly are doing just fine. They’re building reserves, developing relationships, negotiating better contract terms, and securing appropriate insurance. They’re adapting to new market realities, even though nobody sent out a memo saying the rules had changed.

You know, thinking about all this… dairy farming has always involved managing multiple risks. Weather, prices, disease pressure—we’ve dealt with all of it. Processor risk is now part of that mix. It’s not fair that we need to worry about this on top of everything else we manage. But fair doesn’t keep the cows milked or the bills paid.

The operations that’ll thrive over the next decade are those that see this risk clearly and prepare for it. Not because they’re paranoid, but because they’re practical. And if there’s one thing dairy farmers have always been, it’s practical.

We’re all navigating this together, even when it sometimes feels like we’re on our own. Your experiences—both the challenges and the solutions you’ve found—they matter to all of us trying to figure this out.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- You’re not paranoid, you’re practical: With 73% of processors gone since 2000, building a $280K cash reserve (200-cow farm) isn’t excessive—it’s the difference between negotiating power and desperation

- The 72-hour window changes everything: Bulk tanks don’t wait—farmers with processor relationships lined up save $0.30/cwt while others take whatever they can get

- Your contract is probably worthless: Add this clause now: “Producer may seek alternative buyers if processor suspends collection 72+ hours” (most processors won’t even notice, but it could save your farm)

- Insurance companies don’t want you to know: Standard farm insurance won’t cover processor bankruptcy—but $5K/year in specialized coverage beats losing $127K in 60 days

- Form a group or die alone: 40-50 farms together have leverage; individual farms are disposable—the Europeans figured this out decades ago

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- $6 Billion Shock: How Nine Days in April Changed Everything for American Dairy – This tactical playbook reveals how to mitigate $6B trade war risk hitting your milk check, focusing on immediate action steps like locking Q1 feed contracts, maximizing component premiums under new FMMO rules, and optimizing technology ROI.

- 2800 Dairy Farms Will Close This Year—Here’s the 3-Path Survival Guide for the Rest – Go beyond short-term survival and choose your long-term lane. This article details the 3-Path Survival Guide—Premium, Efficiency, or Strategic Exit—using Rabobank data to help mid-size farms decide which structural model is financially sustainable for them through 2027.

- The Future of Dairy: Lessons from World Dairy Expo 2025 Winners – Learn how World Dairy Expo winners are eliminating processor risk entirely. This piece highlights the McCarty Method of vertical integration (on-farm condensing) and strategic genomics, offering scalable lessons in cutting costs, improving employee retention, and building real resilience.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!