Lactalis just sealed a $4.9B deal that’ll reshape every dairy contract in Oceania—here’s what it means for your farm.

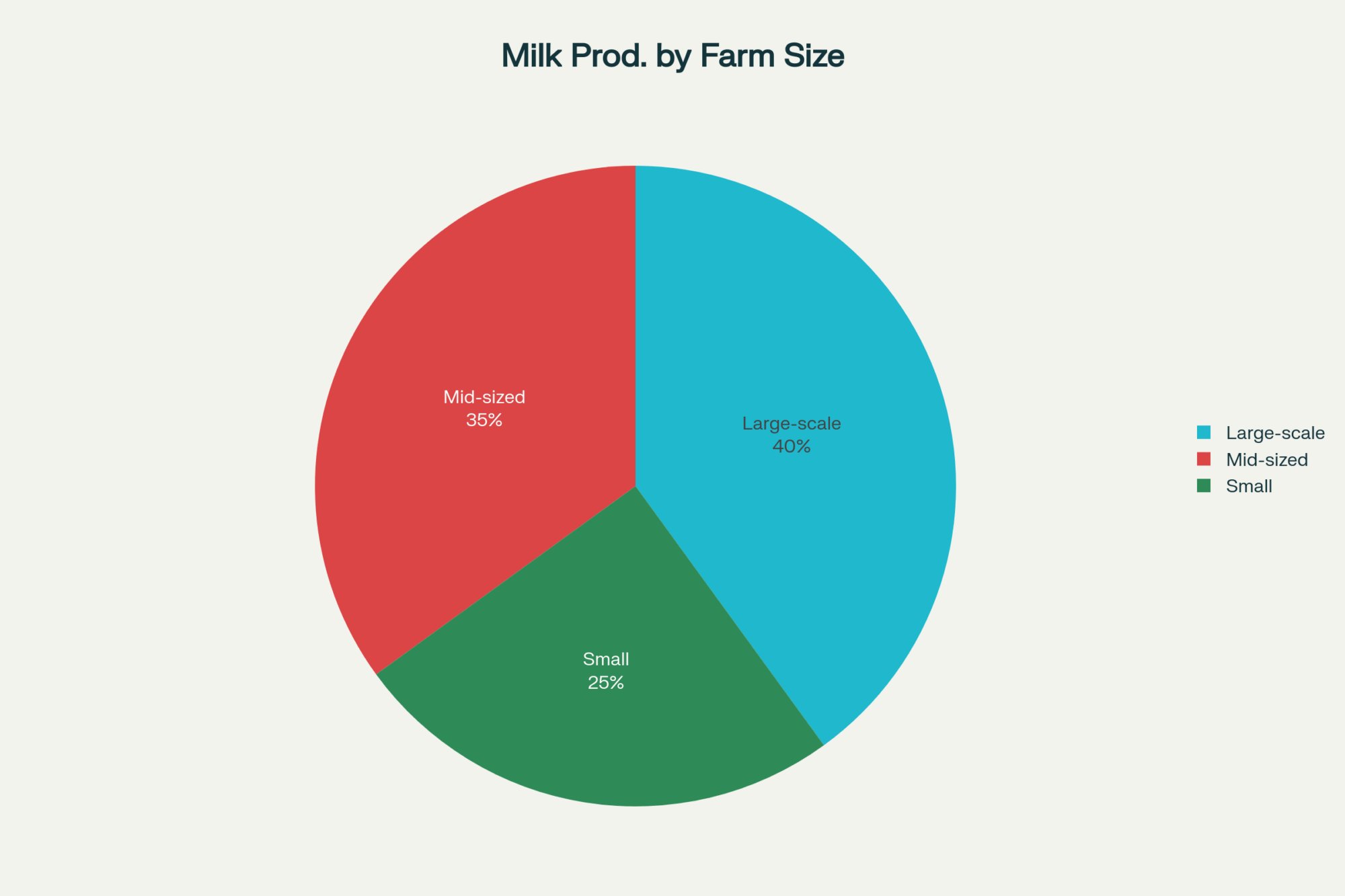

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Look, I’ll cut right to it—Lactalis just grabbed Fonterra’s Mainland Group, and this changes everything about who controls your milk contracts. We’re talking about a company that now commands distribution from Queensland to Tasmania, with brands like Mainland and Kāpiti under one roof. Milk prices are sitting pretty at A$8.60-8.90/kg MS this season, but here’s the kicker—feed costs are up over 20% in Victoria and NSW. What this means is simple: if you’re a large-scale producer pumping 3 million liters or more with solid butterfat numbers, you’re golden. But smaller operations? You better start thinking specialty markets or direct sales, because the commodity game just got tougher. The deal closes late 2025, and how you position yourself in the next 6-12 months will determine whether you’re thriving or scrambling.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- Large-scale farms are in the driver’s seat—operations producing 3 million liters or more annually with consistent 4.2% butterfat will be Lactalis’s preferred suppliers; start negotiating volume commitments now before the competition heats up.

- Mid-sized producers face a crossroads—if you’re in that 1-3 million liter range, you’ve got maybe 18 months to either find partnership opportunities or carve out specialty niches where personal relationships still count.

- Feed cost management is critical—with input costs increasing by 20% or more in key regions, optimizing your feed sourcing and storage strategy could be the difference between profit and breaking even in this new landscape.

- Direct-to-consumer is your ace card—smaller operations should start building specialty product lines and farm-gate sales now; boutique cheese operations in Tasmania and Adelaide Hills are already proving this works while commodity margins shrink.

Lactalis has cleared its final regulatory hurdle to acquire Fonterra’s Mainland Group, which includes major brands like Mainland, Kāpiti, and Perfect Italiano. This move will fundamentally reshape the dairy landscape across New Zealand and Australia upon the deal’s closure later this year.

After months of strategic maneuvering, Lactalis secured approval from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission in July 2025, clearing a critical regulatory hurdle for the acquisition.

Mainland Group is a dominant player in Oceania’s dairy market, with the business generating NZ$4.9 billion in revenue in FY24. The company holds a significant market share across premium cheese and dairy categories in Australia and New Zealand, providing Lactalis with an unprecedented distribution network spanning from the top of Queensland to the tip of Tasmania.

Fonterra’s Retreat and the Economics of Consolidation

Fonterra is deliberately pulling back from consumer retail to focus more heavily on B2B dairy ingredients and foodservice sectors, which promise steadier margins and less volatility (Dairy Reporter, 2024). This strategic pivot comes as producers and processors alike struggle with tightening economic conditions on the ground.

Australian milk prices currently average between A$8.60 and A$8.90 per kilogram of milk solids for the 2025/26 season. Meanwhile, feed costs have increased by over 20% in key production regions, such as Victoria and New South Wales. ABARES data indicate that smaller processing facilities incur unit costs that are around 10-15% higher than those of their larger counterparts, highlighting the challenging operational environment.

Local processors in Victoria and southern NSW are under pressure to scale up, merge, or risk falling behind as consolidation tightens margins and distribution channels.

The High-Stakes Integration Challenge

Integration isn’t easy. James Patterson, a dairy industry consultant and former Fonterra executive, emphasizes that success depends on cutting costs while maintaining Mainland’s premium brand appeal. Any missteps risk eroding years of hard-earned customer loyalty (Dairy Reporter).

Lactalis has demonstrated expertise in integration through previous acquisitions such as General Mills’ US yogurt business and Kraft Heinz’s cheese operations, typically achieving 8-12% cost reductions within two years. This challenge is not theoretical; Lactalis was recently fined nearly A$1 million for dairy code compliance issues, a stark reminder of the complexities of Australia’s regulatory environment.

What This Means for Your Operation

Bold decisions matter here. Large-scale operations producing 3 million liters or more annually with consistent butterfat levels have become strategic suppliers prized by Lactalis’s procurement model. Think of the 4+ million-liter operations in Gippsland delivering consistent 4.2% butterfat—they are positioned perfectly to benefit from this consolidation wave.

Conversely, smaller operations producing under 2 million liters need to consider scaling or pivoting toward specialty or direct-to-consumer markets—an increasingly viable strategy in regions like Tasmania’s Huon Valley and the Adelaide Hills, where boutique cheese operations are thriving.

Mid-sized operations in the 1-3 million liter range face the toughest decisions: either find partnership opportunities to achieve scale, or carve out specialty niches where personal relationships still matter.

Why the Competition Couldn’t Compete

Bega’s partnership with FrieslandCampina appeared promising on paper—combining local market knowledge with international capital. But they couldn’t match Lactalis’s regulatory sophistication and proven integration expertise. Meiji’s financial strength was notable, but their regional presence in Oceania was insufficient for this scale of acquisition.

What’s particularly noteworthy is this wasn’t just about who could bid the highest—it came down to execution credibility and demonstrated capability to navigate complex regulatory environments.

The Bottom Line

This acquisition signals a fundamental shift—not just in market share but in who holds power over contracts, pricing, and policy influence going forward.

Large producers should expect more stable contracts and potentially better margins through volume commitments. Mid-sized operations need to explore partnerships or niche markets within the next 12-18 months. Smaller farms must focus on differentiation strategies—such as direct sales, specialty products, or premium positioning—because the commodity milk market is becoming increasingly challenging.

The deal is expected to close in late 2025, and integration challenges will likely create both disruption and opportunity through 2026. How you position yourself in the next 6-12 months could determine whether you’re thriving or struggling when the dust settles.

However, this conversation is just getting started. To thrive, you have to stay ahead of the curve, not play catch-up. What are you seeing in your region? How are you preparing for these changes? Drop us a line—we want to hear directly from operators on the front lines of this industry shift.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- The Feed Dilemma: Unlocking Profitability in an Era of High Input Costs – This piece breaks down the economics of high input costs, revealing proven tactics for optimizing rations and reducing waste. It provides practical strategies to protect your farm’s profitability in the tight-margin environment created by market consolidation.

- Beyond the Milk Check: Decoding Processor Strategy to Maximize Your Farm’s Value – Go behind the curtain of processor strategy. This analysis demonstrates how to decode your processor’s business model and leverage that knowledge to negotiate better contracts, ensuring you capture maximum value in a newly consolidated market.

- The Digital Dairy: How On-Farm Tech is Creating the Next Wave of Value-Added Products – For farms looking to pivot, this article explores how emerging on-farm technologies can create new, high-margin revenue streams. It provides a forward-looking guide to building a future-proof, value-added business model beyond the commodity market.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!