$100K cooling system? Italian dairy families invested $50K in cheese vats instead—and DOUBLED profits.

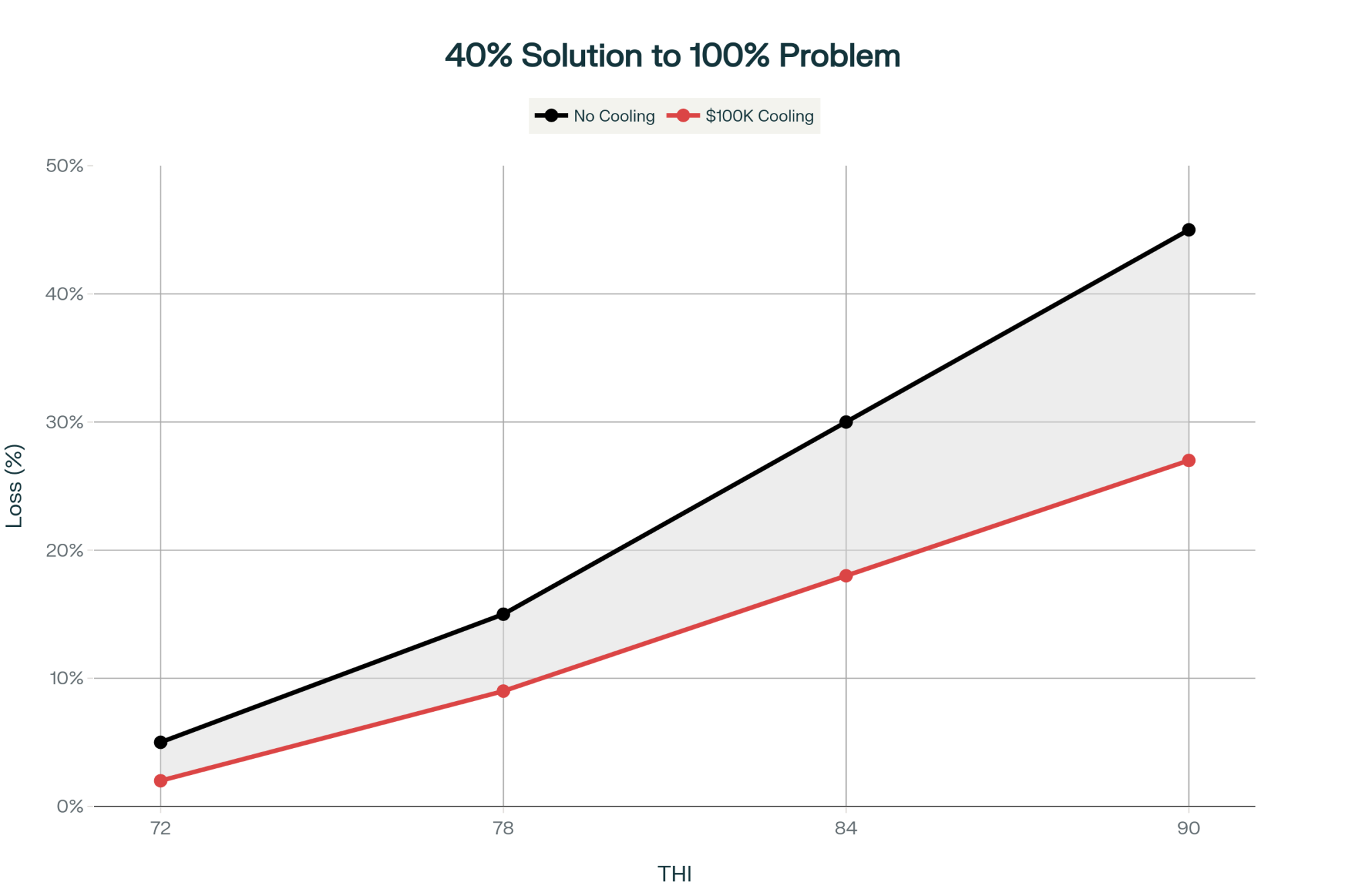

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: North American dairy faces an Italian preview: fourth-generation cheesemakers abandoning volume for value as cooling systems prove only 40% effective against extreme heat, exposing our industry’s dangerous bet on technology over adaptation. Wisconsin’s brutal arithmetic—7,000 farms vanished while production rose 5%—reveals that mid-sized operations carrying debt below the $18/cwt profitability threshold are mathematically doomed by 2030. Producers face three proven escape routes: scale to 2,000+ cows with $500K investment, pivot to seasonal/specialty for premium markets despite 30% volume cuts, or capture 10X commodity prices through on-farm processing. The clock is unforgiving—Q1 2026 marks the last moment to choose your path and begin the 3-4 year transition before market forces choose for you. Water scarcity, dependence on immigrant labor, and soil depletion compound the timeline, while genetic decisions force an uncomfortable trade-off: bulls whose daughters survive the August heat produce 500kg less milk annually. Italian farmers who accepted this reality doubled their profits; those who fought it with technology are gone. Your cooling fans won’t save you in 2030—but choosing the right business model today might.

You know, I’ve been following what’s happening with dairy farmers in southern Italy, and it’s got me thinking about our own future here. These multi-generation families—some going back to their great-grandfathers—they’re not just adding bigger fans when the heat and drought hit. They’re completely rethinking how they farm.

Here’s what’s interesting: instead of fighting the climate with more technology, many are shifting to seasonal production with those beautiful heritage breeds like Podolica cattle. Moving from fresh mozzarella to aged cheeses that hold up better in both heat and volatile markets. Less milk, sure, but products that work with the reality they’re facing.

The European agricultural monitoring agencies have been tracking this, and the numbers tell a story. Summer milk production in Italy’s heat-affected regions has been declining by double digits over the past few years, and there’s been a steady increase in farms closing or transitioning. It’s not a crisis as much as it’s a transformation—and as I talk with producers from Vermont to California, I’m hearing remarkably similar questions bubbling up.

The insights I’m sharing here draw from extension research, industry data, and patterns I’ve observed across numerous dairy operations over recent years.

The Timeline We’re All Watching

Let me share what the research is telling us about the next decade, because this window for making strategic choices—it’s narrower than most of us realize.

The land-grant universities have been remarkably consistent. Cornell, Wisconsin, Minnesota—they’re all pointing to about a five-year period where we can still be proactive. After that? Well, the market and Mother Nature start making more of the decisions for us.

According to the U.S. Global Change Research Program’s latest work, by 2030, we’re looking at average temperature increases of 1.5 to 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit across dairy country. Now that might not sound like much sitting here, but translate that to your barn in July. We’re talking measurable production losses—maybe just over one percent nationally to start, but it won’t hit everyone equally. Some regions will feel it harder.

By 2040—and this is what really gets my attention—the modeling from multiple universities suggests heat stress days could double or even triple from what we see now. Instead of managing through 10 or 15 tough days, imagine 30 or 40 where even your best management can’t fully compensate.

Producers I’ve talked with in Wisconsin are already seeing this shift. What used to be a handful of brutal days has turned into weeks where the cows just can’t catch a break. And those power bills? Several operations tell me their cooling costs last summer ate up everything they’d saved for improvements.

Here’s the sobering part: research from both U.S. institutions and international teams, including work from Israel’s Institute of Animal Science, published in recent years, shows that even effective cooling technology mitigates only about 40% of production losses during extreme heat events. That’s not the technology failing—that’s just the reality of what we’re up against.

That Six-Figure Cooling System Question

So let’s talk about what everyone’s pushing—these comprehensive cooling systems. I’ve been looking at the real numbers from extension programs, and honestly, the range is eye-opening.

For smaller operations, say 50 to 100 cows, Penn State Extension and others offer basic fans and sprinklers at about $10,000. That’s manageable for many. But for mid-sized farms? The backbone of many communities? You’re looking at $100,000 or more for a system that really makes a difference. Tunnel ventilation, sophisticated soakers, smart controls—it adds up fast.

What’s particularly challenging is the cash flow math. Farm financial analyses from multiple universities suggest you need fifty to seventy-five thousand in annual free cash to justify that kind of investment. Looking at current milk checks versus input costs… that’s a pretty select group right now.

Many producers tell me the same thing: taking on massive debt for a system that only solves part of the problem feels more like gambling than adapting.

Though I should mention, for some larger operations, the investment does pencil out. Operations with 2,000-plus cows that have invested in comprehensive cooling report maintaining over 90% of their baseline production through heat waves. At that scale, with those milk volumes, the economics can work.

Breeding for the Heat

Before we dive into alternatives, let’s talk genetics—because this is where the future really gets interesting.

Recent research from the USDA and multiple universities shows we’re at a crossroads in heat-tolerance breeding. The good news? Genetic variation for heat tolerance exists, and it’s heritable enough to make selection worthwhile. Studies from Florida show that 13-17% of the variation in rectal temperature during heat stress comes from genetics—that’s lower than milk yield heritability (around 30%), but it’s significant enough to work with.

What’s really eye-opening is how different bulls’ daughters perform under heat. The latest genomic evaluations show that the most heat-tolerant bulls have daughters with 2 months longer productive life and over 3% higher daughter pregnancy rates than the least heat-tolerant bulls. But here’s the trade-off—their predicted transmitting ability for milk is typically 300-600 kg lower, depending on the sire.

University research has identified a critical finding: genetic variance for fertility traits increases under heat stress. This means sire rankings change entirely depending on temperature conditions. A bull whose daughters excel for pregnancy rates in Wisconsin might tank in Texas heat, while another bull’s daughters maintain fertility specifically under stress conditions.

The industry is responding. Genomic evaluation companies now provide heat tolerance indices, with breeding values ranging approximately from minus one to plus one kilogram of milk per day per THI unit increase, according to the latest industry reports. That spread between the best and worst—it’s significant when you’re facing 40 heat stress days.

But here’s what nobody’s talking about openly: the relentless selection for production has made our cows increasingly heat sensitive. Selection indices now include longevity, fitness, and health traits, but we’re still playing catch-up. Progressive producers are prioritizing moderate frame sizes—those efficient 1,350- to 1,500-pound animals that maintain production while handling heat better than the larger frames that were historical breeding targets.

The question is: are you willing to trade some production potential for cows that actually survive and breed back in August? Because that’s the real decision genetics is putting in front of us.

Three Alternatives That Are Actually Working

This is where it gets interesting, because what I’m seeing isn’t theoretical—it’s happening right now on real farms.

Working With the Seasons

The seasonal production model adopted by some Italian producers seemed backward at first. Deliberately dry off cows during peak summer? Accept 25-30% less annual milk? But then you look at the complete picture.

Extension studies from Vermont, Wisconsin, and Michigan show feed costs dropping three to five dollars per cow per day during grazing seasons. Labor needs ease up considerably. And here’s what’s really interesting—market data from various cooperatives shows processors now paying 10-15% premiums for seasonal, grass-based milk. The market’s recognizing quality differences.

I’ve been tracking operations in Vermont and elsewhere that made this shift. Despite producing less milk than year-round neighbors, many report their net income actually increased—sometimes by 20% or more. As one producer put it to me, “When you stop fighting the weather every day, when the cows are comfortable in August, everything changes. The stress level drops for everyone.”

Value-Added on the Farm

Let’s talk about processing, because the economics here can be compelling for the right operation. We all know commodity milk prices—eighteen to twenty dollars per hundredweight when things are decent, less when they’re not. But producers who bottle and sell direct? Industry surveys from the American Cheese Society and extension case studies consistently show returns of $60 to $90 per hundredweight equivalent. That’s not marginal improvement—that’s a different business entirely.

The investment for basic processing ranges from 50 to 100 thousand, about what you’d spend on cooling. But here’s the difference—Penn State feasibility studies and Wisconsin DATCP analyses show that many processors recover that investment in 6 to 12 months when they’ve got their markets lined up.

Operations that have gone this route tell me the aged cheese they make during spring flush can bring ten times what they’d get from the co-op. Ten times. Now, it takes skill, the right permits, and consistent marketing, but for those who make it work, it’s transformative.

Going Direct to Consumers

What’s really changed—and this deserves attention—is the regulatory landscape. The Farm-to-Consumer Legal Defense Fund now tracks over 30 states that permit some form of direct dairy sales. That’s up from basically zero fifteen years ago.

The price differential almost seems unfair to discuss. Raw milk, when it’s legal and properly marketed, sells for $8 to $12 a gallon directly to consumers. Compare that to the $1.80 or $2 equivalent at the farm gate.

What’s encouraging is you don’t need to convert everything. Producers successfully moving just 20% of their milk to direct channels report that it completely changes their financial stability. It’s about diversification that actually means something.

Your Three Pathways: A Quick Comparison

| Pathway | Investment Required | Typical Payback | Volume Change | Best If You Have… |

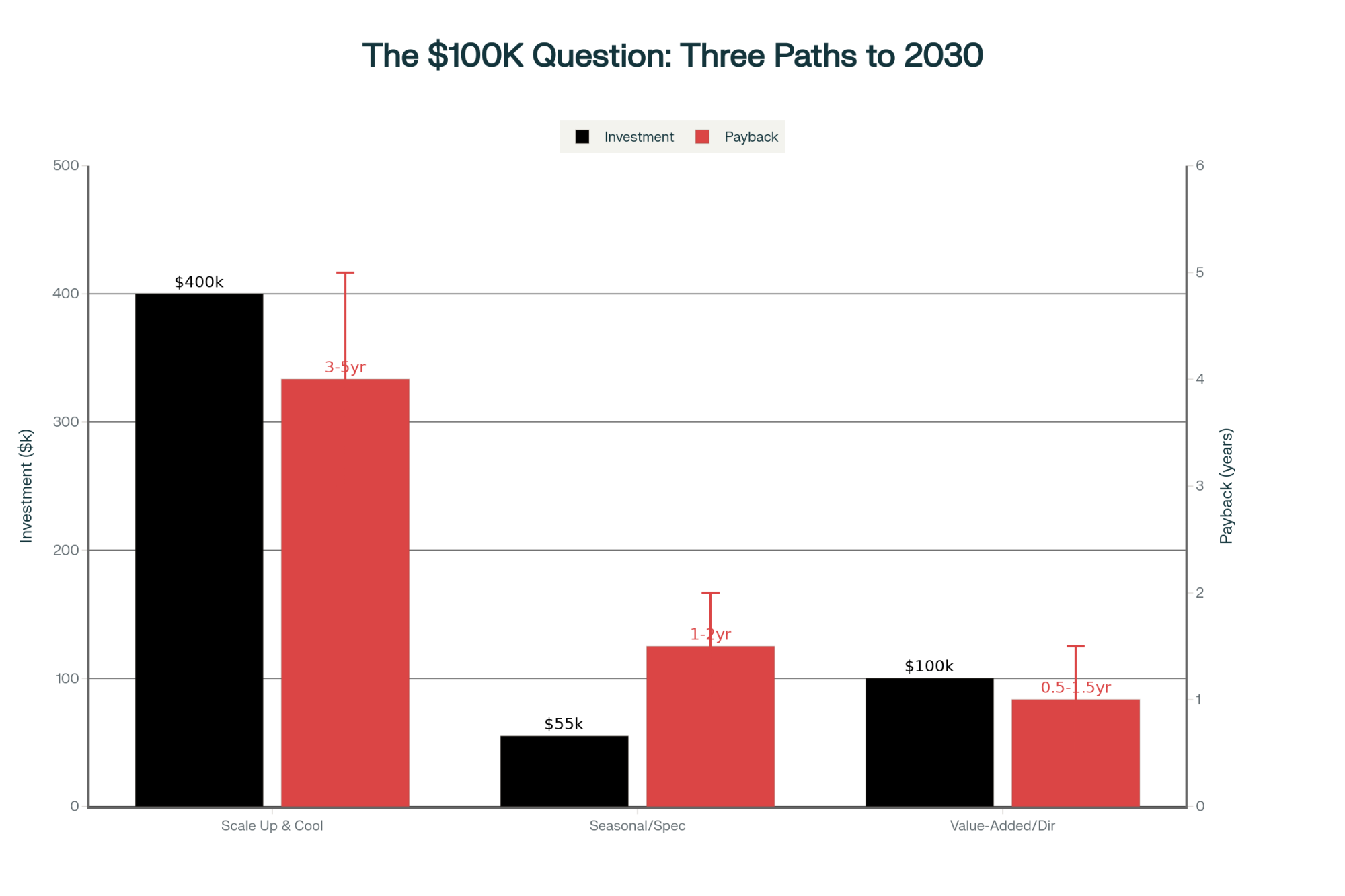

| Scale Up & Cool | $300k – $500k | 3-5 years | Maintain/Increase | Strong cash flow, <50% debt |

| Seasonal/Specialty | $30k – $80k | 1-2 years | -25% to -30% | Pasture access, flexible mindset |

| Value-Added/Direct | $50k – $150k | 6-18 months | -20% to -30% | Market access, marketing skills |

The Math of Consolidation is Ruthless

Let’s stop dancing around this. If you’re mid-sized and carrying debt, the climate is coming for your margins—and the numbers don’t lie.

Research from Wisconsin and Cornell agricultural economists identifies the exact break points where your operation becomes a casualty. When your realized milk price consistently runs below eighteen dollars per hundredweight, you’re not adapting—you’re bleeding equity. When income over feed costs drops below seven or eight dollars per cow per day, you can’t service debt anymore. And when debt-to-asset ratios climb above 50%, banks won’t even return your calls for upgrade financing.

These thresholds aren’t suggestions—they’re mathematical realities derived from thousands of farm closures.

Wisconsin’s experience is the canary in the coal mine. USDA-NASS data shows the state hemorrhaged 7,000 dairy farms between 2015 and 2023, yet milk production hit records. Those weren’t random failures—they were mid-sized family operations caught in the consolidation vice. Meanwhile, according to the 2022 Census of Agriculture, operations with over 1,000 cows now control two-thirds of the nation’s milk supply, up from 57% just five years back.

The consolidation winners aren’t shy about it either. Producers who’ve successfully scaled tell me that at 2,000+ cows, they access technology and leverage that transforms the entire business model. As one mega-dairy owner put it bluntly, “Scale gave us options. Everyone else just has hope.”

If you’re sitting at 200 cows with 60% debt-to-asset and milk at $17.50, the math is already written. The question isn’t whether you’ll consolidate or exit—it’s how much equity you’ll have left when you do.

“Sometimes working with natural systems instead of against them might be the smartest strategy of all.”

Three Constraints We’re Not Discussing Enough

Beyond climate and economics, three pressures deserve more attention.

Water Is Everything

The situation with the Ogallala Aquifer has shifted from concerning to critical. U.S. Geological Survey data from 2024 shows that recoverable water continues to decline. Kansas reported drops exceeding a foot across wide areas last year. This directly affects irrigation for feed and long-term dairy viability.

In California, UC Davis research documents that Central Valley groundwater depletion is accelerating beyond sustainable levels. The San Joaquin Valley alone has lost over 14 million acre-feet of groundwater storage since 2019. We’re looking at maybe 15-20 years before water, not heat, determines who stays in business there.

Producers in those regions tell me water is now their first consideration every morning—something their grandfathers never worried about.

Labor Challenges Keep Growing

Industry analyses from the National Milk Producers Federation and Texas A&M converge on this: roughly half of dairy’s workforce consists of immigrant labor, and those workers produce the vast majority of our milk. When you overlay visa challenges and local labor shortages, smaller operations feel it first and hardest.

Rising labor costs—an extra two or two-fifty per cow per month in many areas—that’s often the difference between black and red ink when margins are already tight.

Soil Health Can’t Be Ignored

This might be our biggest long-term challenge. FAO data from 2024, backed by Iowa State research, shows soil organic carbon down by half in many agricultural regions. The fix—regenerative practices—takes three to five years and serious capital before you see results in forage quality.

The operations that most need soil improvement often lack the financial cushion to weather that transition. It’s a tough spot.

Making Your Own Decision

After countless conversations with producers and advisors, certain patterns have emerged to help frame decisions.

Suppose you’re consistently seeing milk prices above eighteen dollars, maintaining income over feed costs above seven or eight dollars per cow per day, keeping debt-to-asset ratios under 50%, and can access three to five hundred thousand in capital. In that case, scaling up with cooling infrastructure might work. But success still requires exceptional management and decent markets.

If those numbers don’t line up but you’re within reach of population centers, have some pasture, and can stomach lower volume for better margins, specialty production models offer real potential. Especially if you can develop that direct channel that provides price stability.

Timing matters. By year’s end, you need an honest assessment. First quarter 2026—decision time. Use 2026-27 for building infrastructure or markets. By 2028-29, you should be transitioning operationally. Come 2030, your model needs to be locked in, because the competitive landscape will be pretty well set by then.

Regional Realities

| Region | Current Heat Stress Days | 2035 Projected Heat Days | Water Crisis Severity | Runway to Adapt | Competitive Advantage |

| Upper Midwest (WI, MN, MI) | 12-15 | 20-25 | Stable | Longest (~10 yrs) | HIGH |

| Plains States (NE, KS) | 20-25 | 35-45 | CRITICAL -1 ft/yr | Short (~5 yrs) | Declining |

| California & Southwest | 30-35 | 45-55 | EXTREME 140 gal/cow | IMMEDIATE (~2 yrs) | Collapsing |

| Northeast (NY, VT) | 8-12 | 15-20 | Favorable | Long (~12 yrs) | HIGHEST |

| Southeast (GA, FL) | 40-50 | 60-70 | Moderate | Already Here (0 yrs) | Experience Leader |

Upper Midwest

Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan—you’ve got the longest runway. University of Minnesota Extension modeling suggests heat stress stays manageable through 2030, and water’s relatively stable. Focus on genetics, targeted cooling in holding areas, and protecting components during stress periods. Current operations average 12-15 heat stress days annually, expected to reach 20-25 by 2035.

Plains States

Nebraska and Kansas dairy operations face a double squeeze—the depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer threatening feed production while heat-stress days increase from the current 20-25 to projected 35-45 by 2040. Kansas State research shows producers here need water strategies yesterday, not tomorrow. Some are already transitioning to dryland-adapted forage systems or relocating operations entirely.

California and the Southwest

Water drives everything here. UC Davis reports show you’re already using 20-30% more water per cow than a decade ago just to maintain production. California dairy operations now consume an average of 140 gallons per cow daily during summer months, up from 95 gallons in 2014. If you haven’t developed a water strategy beyond hoping for wet years, you’re behind. The next five years will force hard choices about value-added production, relocation, or partnering with operations that have water rights.

Northeast

Cornell’s work shows you maintaining favorable conditions through 2035. That’s an opportunity—develop specialty markets now while you have the advantage. The artisan cheese growth in places like the Hudson Valley shows that real market appetite exists. New York State Department of Agriculture reports specialty dairy operations increased 35% between 2022-2024.

Southeast

You’re living tomorrow’s challenges today. Georgia and Florida operations already manage 40-50 heat stress days annually. Every smaller operation surviving your heat and humidity has developed strategies that the rest of us need to study. Your experience is our roadmap.

Resources for Moving Forward

Decision Support Tools:

- Cornell’s IOFC Calculator (available through the PRO-DAIRY website)

- Penn State’s Enterprise Budget Tool for processing feasibility

- USDA Climate Hubs’ regional adaptation resources

- National Young Farmers Coalition’s direct marketing guides

The Bottom Line

Climate change isn’t just forcing operational changes—it’s driving fundamental shifts in business models. The successful producers I see aren’t trying to preserve yesterday’s approach with tomorrow’s technology. They’re finding what works with emerging realities.

The choice isn’t simply to get bigger or get out. It’s about finding the model that fits your resources, market access, and what lets you sleep at night. For some, that’s scale and technology. For others, it’s lower volume with higher margins through differentiation.

What those Italian dairy farmers are teaching us isn’t that we should all make aged cheese or switch breeds. It’s that one-size-fits-all responses might be less adaptive than thoughtful, farm-specific strategies.

Your operation’s future depends on choosing a path, but mostly on choosing soon enough to control how you implement it. The changes are coming either way.

This is about preserving not just farms but farming as a viable way of life. Sometimes that means producing less to preserve more. Sometimes it means completely rethinking what success looks like.

And sometimes—just sometimes—it means recognizing that working with natural systems instead of against them might be the smartest strategy of all.

Key Takeaways:

- Cooling = 40% solution to a 100% problem: That $100K system you’re considering? It only stops 40% of losses at extreme temps. Italian farmers who invested in $50K cheese vats doubled their income instead.

- Three models survive 2030—pick one NOW: Mega-dairy (2,000+ cows), seasonal/specialty (30% less milk, 20% more profit), or value-added (10X commodity prices). Middle ground is extinction.

- The $18/cwt line divides living from dying: Below it, with >50% debt, you’re already bleeding equity daily. Wisconsin lost 7,000 farms in this death zone while production rose 5%.

- Genetics force a brutal trade: Accept 500kg less milk for cows that survive August, or chase maximum production with daughters that won’t breed in heat. There’s no middle option.

- Water kills operations faster than heat: Ogallala Aquifer -1ft/year. California dairy: 140gal/cow/day. Your 2030 survival depends more on water rights than cooling technology.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Heat Stress 2.0: Why Your Current Cooling Strategy Is Costing You Big Money – Reveals actionable advanced cooling protocols beyond basic fans, detailing how intelligent soaking systems reduce water use by 70% and why dry cow cooling offers a proven 5.67-year payback to protect future lactation cycles.

- Decide or Decline: 2025 and the Future of Mid-Size Dairies – Provides specific financial strategies for the “mid-sized squeeze,” demonstrating how lifting Income Over Feed Cost (IOFC) to $10 can add $820,000 in annual margin and outlining the exact debt-to-asset ratios required for sustainable expansion.

- U.S. Dairy Genetic Evaluations Set for Historic Reset in April 2025 – Explains the massive shift in Net Merit $ (NM$) indices, detailing why fertility and livability traits are receiving a “20% promotion” and how to recalibrate your sire selection benchmarks to align with the new economic reality.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!