How an Overpriced Italian Specialist Became Worth Billions (And Why His Story Could Save Your Herd from What’s Coming Next)

You know that moment when you realize you’ve been doing everything wrong?

Farmers across Yorkshire had it in 2008, standing in empty barns, watching auctioneers sell off what was left. The high-producing daughters of those “bargain” bulls they’d bought five years earlier? They’d crashed and burned when feed costs doubled and milk prices tanked. Spectacular production for two lactations, then… nothing. Metabolic disasters. Fertility nightmares. Udders that looked like they’d been through hell.

Meanwhile, their neighbors—the ones who’d invested a premium £40 per straw in that expensive Italian specialist back in ‘98—were still milking. Still profitable. Fourth and fifth lactation cows just quietly doing their job while everyone else’s genetics fell apart.

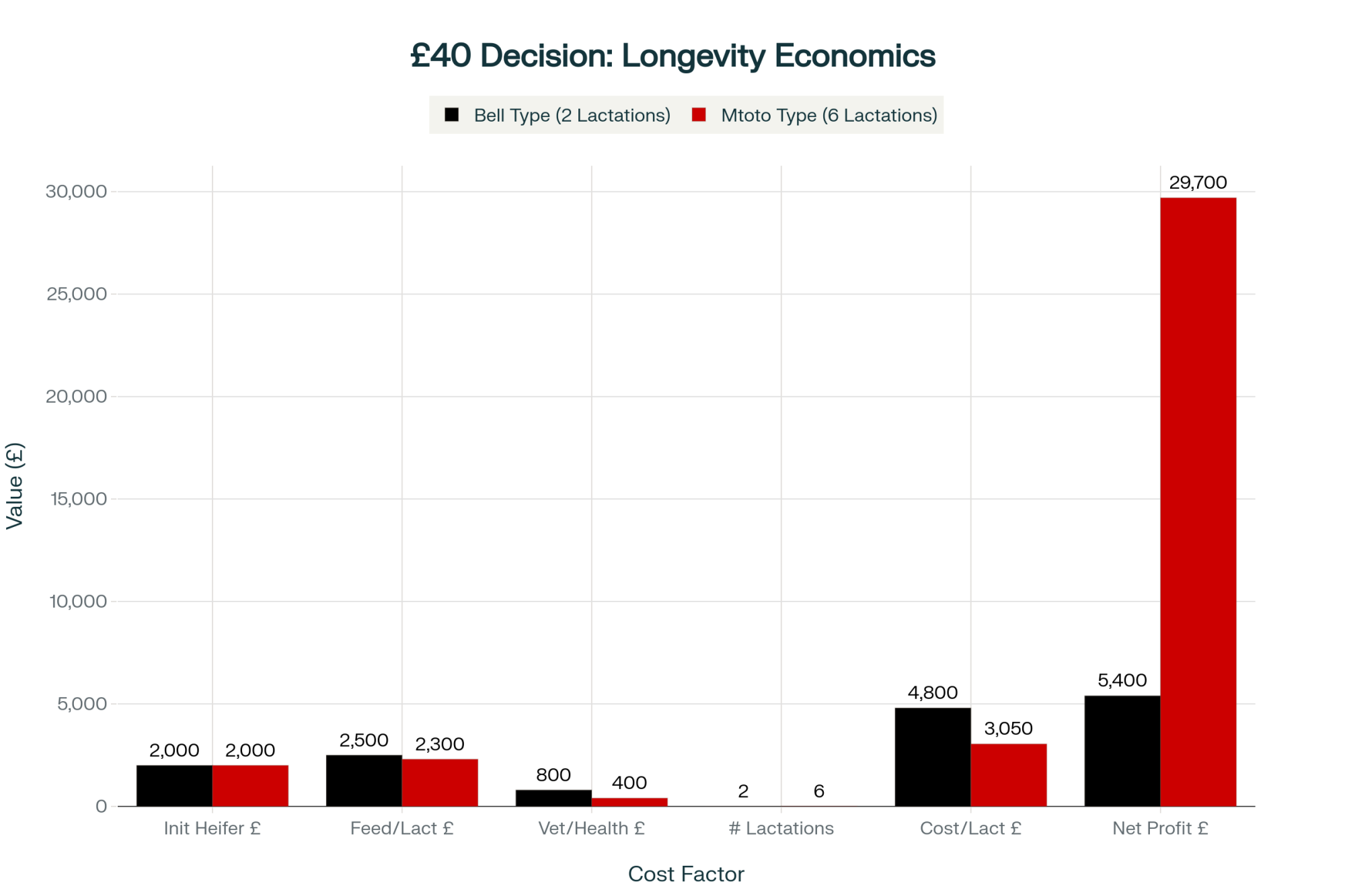

The difference between those farms came down to one decision in October 1998. Whether to spend a painful £40 on Carol Prelude Mtoto—a massive premium when neighbors were buying “bargain” bulls for a tenner—or take the easy route and buy the cheaper, high-production sensations everyone else was using. At £40 per straw when standard proven bulls cost £10-15, Mtoto was a contrarian investment most farmers couldn’t justify.

Here’s the thing… the spreadsheets were dead wrong.

What happened with Mtoto isn’t just breeding history. It’s playing out again right now, except this time we’re using genomics to make the same mistakes at digital speed. And if you’re not seeing it in your barn yet, trust me—you will. We all will.

When Production Became a Disease

Let’s talk about what the industry looked like when Mtoto showed up. Picture walking into any tie-stall operation in the mid-’80s. You know that smell, right? Silage, manure, and something else that hits you wrong. Then you see them—Bell daughters everywhere.

Christ, those cows could milk. Carlin-M Ivanhoe Bell was putting 1,700 pounds above average into bulk tanks across North America. By the late ’80s, his genetics appeared in the pedigrees of nearly 30% of the Holstein population. Every AI stud was pushing his genetics hard. Every producer wanted them.

Producers who managed operations during that era tell the same story. “Those first two years were like Christmas morning every day,” they remember. “You’re watching the tank fill up, doing the math in your head, thinking you’ve figured out this whole dairy thing.”

But here’s what nobody wanted to admit—Bell daughters were frail. Narrow through the chest. Fragile, really. Their udders? By the second lactation, they were hanging so low you worried they’d drag on concrete. And third lactation… if they made it that far.

“It was like a battlefield,” producers from that era still say. “Cows down with milk fever everywhere. Others were standing with their legs all splayed out, trying to hold up udders that had completely broken down. We were getting maybe two, two and a half lactations before they were done.”

The math was brutal once university researchers ran the numbers. Cornell and others documented that Bell daughters lived significantly shorter, productive lives. In some cases, 2-3 years less than balanced genetics. All that spectacular production didn’t mean squat when you’re constantly buying replacements.

Farmers still shake their heads when they talk about it: “The production was so incredible those first couple years, we kept telling ourselves it was worth it. By the time we figured out what we’d done to our herds, Bell genetics were everywhere. There was no going back.”

The industry had created production monsters wrapped in tissue paper. And almost nobody saw the correction coming from, of all places, Italy.

The Italian Accident That Changed Everything

July 13, 1993—a bull calf gets born in Italy, in that region where they make real Parmigiano. Nothing special about him. Average size. Production genetics that were, let’s be honest, pretty mediocre.

But Carol Prelude Mtoto had something hidden that you couldn’t see at birth—and I know this sounds weird—but it was all about how tight the teat ends would close after milking.

Stay with me here because this matters…

You know how after you pull the milkers off, there’s that window—maybe an hour, an hour and a half—where the streak canal’s still open? That’s when bacteria can cruise right up into the udder, especially when the post-milking spray misses the target. It’s like leaving your barn door open in a thunderstorm while the cows are lying in wet bedding.

Now, some bulls transmit daughters with loose, relaxed teat ends. Great for parlor throughput—those cows milk out fast. But they’re mastitis magnets. Others, like Mtoto? His daughters had tight teat closure. Annoyingly tight. Slow milkers that drove parlor managers crazy.

Producers in the Parma region called them ‘hard milkers’ and constantly complained about them. But this was the biological trade-off for survival. While neighbors were burning through antibiotics, treating mastitis every damn day, those Mtoto daughters just kept producing clean milk. Year after year. No treatments. No culled quarters. No cell count problems.”

The economics were invisible until you actually sat down and did the math. That extra couple of minutes of milking time? Maybe €30 a year in labor. But the vet bills you didn’t have, the cows you didn’t cull, the extra lactations you got? That was €2,000-3,000 in additional profit per cow. Per cow!

Breeding for Survival, Not Show Scores

But here’s what really made Italian breeding different…

Over 80% of Italian milk wasn’t going into retail jugs—it was becoming Parmigiano Reggiano, Grana Padano. Those Protected Designation of Origin cheeses with regulations so strict they make your bank’s lending standards look relaxed. And those cheese factories? They’d reject your milk flat-out if the cells were too high. When you’re aging cheese for two, three years, protein content matters way more than volume.

Italian dairy leaders from that era explained it simply: “We weren’t breeding for those production records Americans chase. We were breeding for cows that could deliver consistent, quality milk for cheesemaking while lasting long enough, actually, to turn a profit.”

Think about it. A cow pumping out 30,000 pounds for two years means absolutely nothing if the cheese factory won’t take her milk.

The Italian approach seemed backwards to those of us chasing TPI—that’s Total Performance Index, basically the dairy world’s report card for Holstein genetics. But when you can’t just throw corn silage at everything, when cheese factories set your market standards, when your family farm has to last another generation… mastitis resistance becomes survival, not luxury.

Mtoto was engineered to fix what Bell broke. His sire, Ronnybrook Prelude—himself a Starbuck son—brought good frame and dairy character. His dam, a Blackstar daughter, brought constitution. And there was Chief Mark back there for udder perfection. It was like someone designed the exact correction the industry needed but didn’t know it wanted.

By ’98, when Avoncroft brought him to Britain, Mtoto had proven himself across Italian herds. His daughters weren’t production champions. They were survivors—lasting when others broke down, staying healthy when others needed constant treatment.

According to UK dairy records from August 2025, his mature proof shows somatic cell scores of -13, a HealthyCow index of +17, and a lameness advantage of +0.7.

The £40 price tag wasn’t cheap. At nearly four times the cost of standard proven bulls, it was basically saying: “This bull solves expensive problems—if you’re willing to pay upfront to avoid them.”

Most farmers weren’t. Who could blame them? Why pay £40 for mediocre production when £10 bought you bulls with spectacular numbers on paper?

The Eight-Year-Old Cow That Changed Everything

Now here’s where it gets interesting…

The Pickford family from Staffordshire had purchased a Canadian heifer, Condon Aero Sharon, recognizing something in her genetics worth investing in. By ’99, Sharon was eight years old, still going strong. The AI companies? They literally laughed at the Pickfords wanting to flush her. “Too old,” they said. “Obsolete genetics.”

Helen Pickford still remembers the conversation: “The reps kept showing us data on first-lactation heifers. Dad just kept saying, ‘But Sharon’s still here, still producing well. These heifers you’re pushing—will their daughters still be milking in eight years?'”

The Pickfords, working with ABS’s St. Jacob’s program, made a decision that defied conventional wisdom. They bred their mature cow to Mtoto—that expensive Italian specialist with mediocre production proofs. They were essentially doubling down on contrarian genetics.

July 23, 1999. Morning mist at Spot Acre Grange in Staffordshire. Sharon drops a speckled bull calf. They named him Picston Shottle. Nothing special happened that day. The industry had moved on to newer, more “cutting edge” genetics. (Read more: From Depression-Era Auction to Global Dominance: The Picston Shottle Legacy)

What came next rewrote everything.

When Customer Satisfaction Beats Computer Models

Shottle goes into progeny testing—five years before you know anything, right? By 2006-2007, when his daughters start milking, the numbers look solid but not earth-shattering. Nothing that screams “generational breakthrough.”

But something weird starts happening across the herds using him…

“Farmers would try ten straws, then call wanting hundreds more,” producers involved in that era recall. “The reorder rate was unlike anything we’d seen.”

Why? Shottle daughters were invisible cows. The ones that never show up on your treatment sheets. They’d milk out at a reasonable speed—faster than pure Mtoto daughters but still measured. Breed back first or second service. Just quietly produce for five, six, or seven lactations.

Wisconsin dairy consultants from that period report visiting herds where farmers had named multiple cows after Shottle—Shottle’s Pride, Shottle’s Dream, you name it. “These cows paid for my kids’ college,” one producer explained. “They’re family.”

Then, in January 2008. USDA CDCB records confirm Shottle achieved the #1 TPI ranking in the United States. A British bull from a mature dam and an expensive, slow-milking Italian sire. He maintained top rankings for multiple consecutive sire summaries. Something that almost never happens.

By retirement? ABS documentation confirms the sale of 1.17 million doses. Industry records indicate over 100,000 daughters across multiple countries. Breed classification data showing 9,674 Excellent daughters through 2014.

The estimated economic impact? Based on daughters’ combined milk production, improved longevity, and reduced health costs across multiple decades, industry analysts calculate the value in the billions globally.

Helen Pickford remembers when Shottle hit #1: “Dad didn’t say much. But that evening, he walked out to Sharon’s stall—she was still with us then, twelve years old—and just stood there with her for a while. She’d lived to see her son become one of the most influential bulls of his generation. You could see it in his eyes… all those experts who said she was too old, that we were wasting money on obsolete genetics? They’d been looking at the wrong numbers all along. Sharon knew. She always knew.”

But here’s what really matters—Shottle proved the industry’s obsession with production indexes was completely backwards. The most profitable bull of his generation came from genetics that everyone said were overpriced and underperforming.

Why His “Failure” Actually Proves His Success

Okay, so here’s the part that’ll mess with your head…

Look up Mtoto’s current proofs in 2025 relative to the modern base. The production numbers have fallen off a cliff due to thirty years of genetic progress. On paper, with negative kilos of milk and fat compared to today’s heifers, he looks like a statistical ghost.

But here’s what you need to understand—the breed average resets every five years. What was “high production” in 1998 is now below average. A bull from 1993 should have negative production numbers in 2025. If he didn’t, it would mean the breed hadn’t improved in thirty years!

Look closer at the health traits. Despite thirty years of genetic progress, his influence on somatic cell count and lifespan remains positive. His SCC score still sits at -13. HealthyCow index at +17. These health advantages haven’t eroded—they’ve become foundational.

It’s actually pretty simple when you think about it. Mtoto’s daughters had such good udders and lasted so long that they became the new normal. What was exceptional in ’98 is now just average—because his genetics lifted the entire breed’s baseline.

University genetics researchers explain it this way: “When we look at current genomic data, genetics from bulls like Mtoto consistently show up in regions associated with udder health and longevity. These aren’t random leftovers. They’re functional genes that survived thirty years of intense selection because they actually work.”

The negative production numbers don’t mean he failed. They mean he succeeded so completely that exceptional became ordinary.

It’s like… you know how milk cost roughly 40-50 cents per gallon in the mid-1960s, while the minimum wage was around $1.25 per hour? Same milk costs $4 now. The baseline shifted. The world moved on. But the foundation—Mtoto’s genetics—stayed put, supporting everything built on top of it.

The Disaster We’re Speed-Running Right Now

And this is what’s keeping me up at night…

We’re doing Bell all over again, except genomics makes it happen at warp speed. No five-year wait to see if daughters work. We’re marketing bulls from birth based on DNA predictions. If those predictions miss something—and they always do—we saturate the breed with problems before anyone notices.

I was at a large operation in the Midwest last month. Beautiful first-calf heifers, genomic tested at birth, bred to the highest TPI bulls available. The herd manager knows that half won’t make it to third lactation. I know it. But those numbers look so good on paper…

The Numbers Game Nobody Wins

Here’s the pattern that’s killing us…

You walk through any modern freestall now—especially these new robotic barns with all the technology—and you see it. Cows with spectacular genomic indexes are struggling through their second lactation. Metabolic disasters, even though we know more about nutrition than ever. Conception rates that require a reproductive specialist just to maintain.

A young producer in central Wisconsin told me last week: “I spent $50,000 on genomic testing and top-ranked semen last year. Half those first-calf heifers are already gone. My neighbor is using bulls ranking #350 with good health proofs? His cows are entering their fourth lactation. I feel like an idiot.”

That’s the reality nobody talks about at the sales meetings.

Producers managing operations across major dairy regions report similar patterns. “Herds using top-10 TPI bulls exclusively are seeing the same thing,” one Wisconsin consultant shared. “Great first lactation, problems by second, gone by third. Meanwhile, daughters from bulls ranking #300-400 with elite health traits? They’re still here after five years.”

Dairy genetics researchers at major universities have been warning about this. They note we’re selecting hard for traits we can measure genomically—production, type—while underweighting survival traits that are harder to predict. It’s Bell 2.0, except faster. More thorough. More dangerous.

Research on Holstein genetic diversity shows concerning patterns. Studies indicate the breed’s effective population size has collapsed to approximately 50-100 animals. We’re one disease outbreak from disaster, still chasing TPI like it’s gospel.

And here’s what really kills me—we know better. We’ve seen this movie before.

The 2025 Mtoto Is Already in Your Catalog

Here’s what keeps me up: the bull we need right now? He’s probably already out there. Ranking #300-something on TPI with elite fertility, great health traits, exceptional longevity, and yeah, moderate production.

Nobody’s using him because we all filter for top-50 and never see him. Plus, he probably costs more per straw than the “bargain” high-TPI bulls that’ll crash in two lactations.

Think what that bull would need today. Daughter pregnancy rates at +3.0 or better. Real metabolic resilience—cows that don’t crash during early lactation. Right teat structure for robots (because let’s face it, that’s where we’re headed). Some heat tolerance for what’s coming climate-wise. Feed efficiency for when corn hits $8 again.

That bull exists. I’d bet the farm on it. But he’s not sexy. He’s not topping lists. He’s probably priced at a premium because the breeding company knows his value. Just like Mtoto was.

As recent industry analysis of the Florida herds after the 2024 hurricane season showed, it wasn’t the highest-producing herds that made it through the storms. It was the ones with resilient genetics that could handle stress. The same will be true for whatever 2026 throws at us.

The Bottom Line

When you drive past what used to be productive dairy land in Yorkshire, It’s all housing development now—”Dairy Farm Estates” or whatever they call it. Makes you want to laugh and cry simultaneously.

Farmers still operating in those areas tell the same story over coffee: “Neighbors laughed at us for paying four times the price for those overpriced Mtoto straws back in ’98. Called it a waste. But when 2008 hit, our Mtoto descendants were still making a profit. Their high-production cows were bleeding money despite putting more in the tank.”

And that’s what this comes down to. The genetics that look expensive today look cheap in retrospect. The “bargains”? They become the mistakes that kill operations.

Standing in barns today where sixth-generation descendants of those Mtoto crosses are still working—no drama, no issues, just consistent production year after year—you realize what actually matters.

It’s not the cow producing 40,000 pounds before crashing. It’s the one nobody notices. Shows up every day for seven years. Breeds back without fuss. Never needs treating. Quietly pays the bills through every crisis.

“Shottle daughters saved farms,” producers who lived through 2008 will tell you flat out. “When feed doubled and milk crashed, operations with higher-producing herds went under. Those moderate-production cows that lasted six lactations? They kept us alive.”

Look, I’m not saying abandon genomics. Production still matters. Innovation matters. We’re not going backwards.

But somewhere in that catalog is a bull that costs more than you want to pay. Doesn’t top any lists. Most of us will skip him for cheaper bulls with better numbers.

The operations that recognize him—that understand survival beats spreadsheets and that premium genetics are worth premium prices—they’ll still be farming in 2050. The ones chasing cheap, high-index perfection? They’ll be case studies in what went wrong.

We’re at the same crossroads as ’98. Climate change is accelerating. Input costs are volatile. Consumer demands are shifting. Regulations tightening. Perfect conditions? They’re ending. Fast.

The question isn’t whether your cattle can hit 40,000 pounds under ideal management.

The question is whether they’ll still be alive and profitable when everything goes sideways. Because—and trust me on this—everything’s about to go sideways.

Your breeding decisions today determine whether your operation survives or becomes suburban development. Whether you’re still milking in 2050 or just a memory.

Carol Prelude Mtoto died peacefully in 2003, never famous outside breeding circles. Shottle passed away in 2014 after a distinguished career. But tonight, across six continents, their descendants are quietly milking. Invisible cows generating visible profits. Proving real genetic worth isn’t measured in show ribbons or rankings.

It’s measured in survival.

The £40 question remains: What are you willing to pay for genetics that last?

The catalog’s open. Your neighbors are ordering those cheap bulls with spectacular numbers. History says that won’t end well for them.

Your move.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- Four times the price, ten times the return: Mtoto’s £40 “waste” became billions in value through daughters that lasted six lactations vs. 2

- The best cows are invisible: They never need treatment, breed back first service, and quietly profit for 7 years—all from “inferior” genetics

- Today’s #1 genomic bull = Tomorrow’s Bell disaster: Half your genomic heifers won’t see third lactation (sound familiar?)

- Your 2026 savior is hiding at #300-400 TPI: Look for DPR +3.0, SCS <2.7, exceptional health traits—yes, he costs triple

- History’s lesson: Farms that bought cheap in ’98 don’t exist; farms that paid a premium are still profitable

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

When Carol Prelude Mtoto arrived in Britain at £40 per straw—four times the normal price—farmers called it highway robbery for a slow-milking Italian bull. Ten years later, only farms that paid for that ‘robbery’ survived the 2008 crisis. The secret: Mtoto daughters lasted six profitable lactations while cheap, high-production genetics crashed after two. His son, Shottle, became the #1 bull globally, generating billions in value from genetics that everyone said were worthless. Today’s genomic selection is making the identical mistake—chasing cheap indexes while premium-priced health genetics get ignored. The bull that saves your farm in 2026 is in your catalog now, overpriced and overlooked, just like Mtoto was.

Learn More:

- August 2025 US Proofs: A Guide to the Real Winners and Winning Strategies – Identify the “invisible” profit-drivers in today’s lineup. This analysis cuts through the hype of the top 10 list to reveal specific genomic and proven sires that balance high indexes with the health and longevity traits necessary for 4+ lactations.

- Bred for Success, Priced for Failure: Your 4-Path Survival Guide to Dairy’s Genetic Revolution – Decide your operation’s future before the market does. This strategic guide outlines the four viable business models (Scale, Niche, Robotics, or Exit) for surviving a market where genetic efficiency is outpacing processing capacity.

- Genetic Revolution: How Record-Breaking Milk Components Are Reshaping Dairy’s Future – Master the new Net Merit 2025 formula. Discover why the industry is aggressively pivoting toward butterfat and feed efficiency, and learn how to align your breeding goals with the new metrics that will determine milk check value in the next decade.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!