Ray Brubacher built three generations by breaking one rule: Stay loyal to people who break their word. He didn’t.

Bob Rasmussen—who’d sold the National Tea Company to A&P for twenty million dollars, as Ray recalled it—had a peculiar way of packing for road trips.

When twenty-five-year-old Ray Brubacher showed up at Rasmussen’s place with his proper leather suitcase, ready for the drive to Lincoln, Nebraska, Rasmussen tossed a crumpled brown paper bag into the back seat and announced that it was his luggage. Toothbrush, toothpaste, clean underwear, and a pair of socks—that’s all he needed.

The story, which Ray loved to tell years later, perfectly captured something essential about the people who built this industry. It wasn’t about the money. It wasn’t about the facilities or the fancy equipment.

It was about seeing what others couldn’t, keeping your word when no one was watching, and understanding that reputation—once built—becomes the only asset that actually appreciates over time.

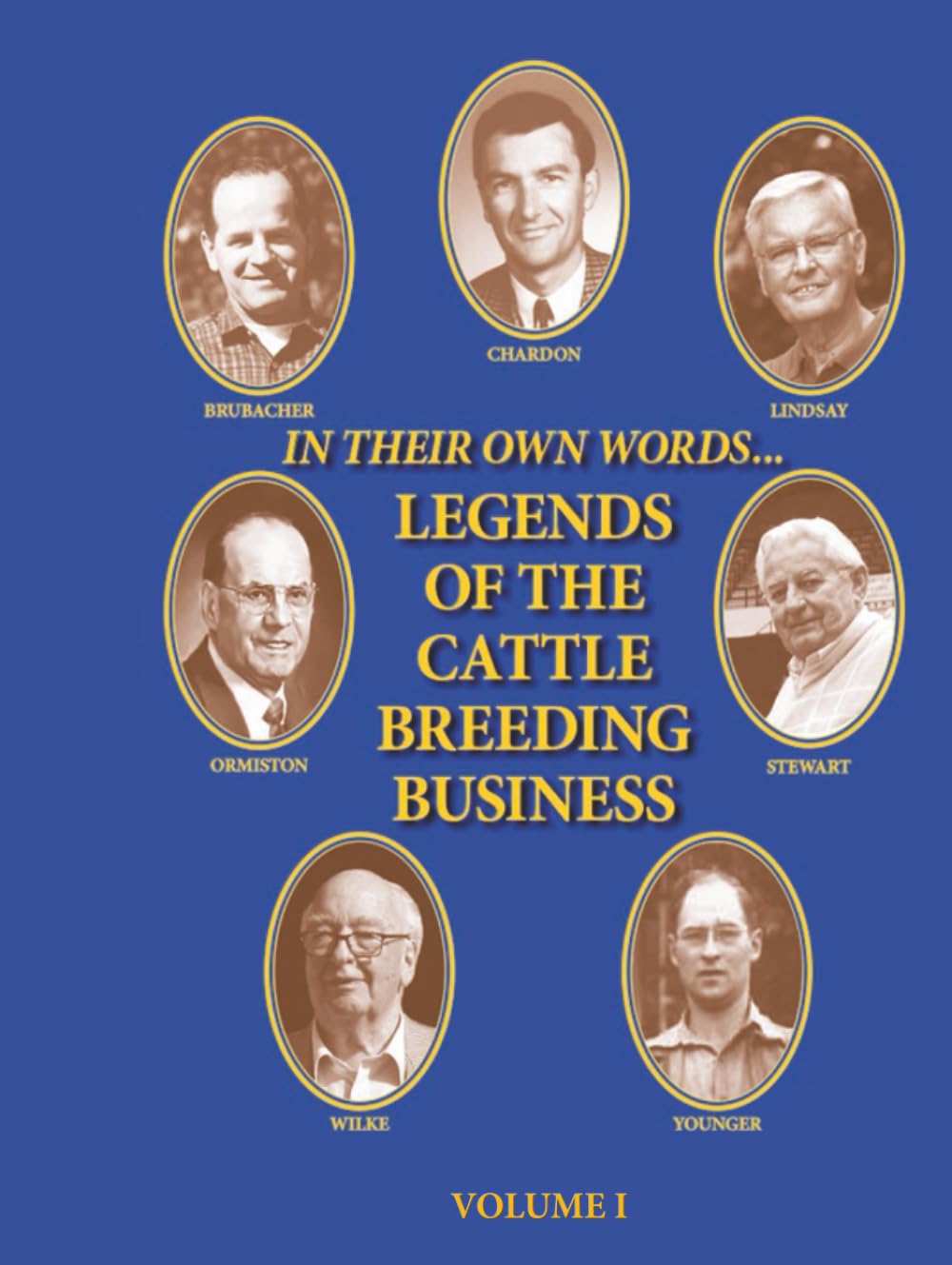

The stories Ray Brubacher loved to tell—preserved in Doug Blair’s interview for “Legends of the Cattle Breeding Business“—weren’t just entertaining anecdotes. They were lessons about what actually matters when you’re building something meant to last.

Here’s the thing about Ray’s story that matters right now—not fifty years ago, but right now in January 2026, when USDA projects U.S. dairy operations will drop from 26,900 (2024) to under 21,000 by 2028. That’s 22% contraction in four years—faster than the 2008-2012 crisis. When contracts replace handshakes and lawyers replace livestock judges. The fundamentals he learned? Still the fundamentals. They just cost more now when you get them wrong.

When Frozen Toes Change Everything

Let me back up to where this really starts—Ontario, early 1920s, a Mennonite community where tradition wasn’t just respected, it was enforced.

Abraham “A.B.” Brubacher climbs into his horse and buggy one bitter Sunday morning for the customary drive to church. By the time he arrives, the tips of his fingers and toes are frozen solid—the kind of bone-deep cold that makes you question every life decision.

The next Sunday? A.B. drove a car.

Got kicked out of the church for it. Became an outlaw in his own community. But here’s what I find fascinating—A.B. wasn’t rebelling just to rebel. This was a man who, as a boy of maybe ten or twelve, would walk a couple of miles out of his way just to see Holstein cattle at a neighbor’s farm. He loved those black-and-white cows with the kind of passion that doesn’t make rational sense unless you’ve felt it yourself.

He understood something most people miss: Loving tradition and embracing progress aren’t contradictions. They’re both necessary if you’re going to survive.

That same stubborn pragmatism drove him to launch an auction business in the early 1930s—right in the teeth of the Great Depression—because he saw breeders struggling to move cattle and thought, well, somebody better do something about that.

His first sale at the Winter Fair Building in Guelph averaged $225, with a top bull bringing $355. Not spectacular numbers, but sustainable. And here’s the kicker—that top bull went to Elmwood Farms in Illinois. Twenty years later, that same farm would hire A.B.’s son and change the trajectory of North American Holstein breeding.

Ray inherited both the stubbornness and the passion. Along with something else: a chip on his shoulder about education that would drive him for the rest of his life.

Grade 8 and Out

Ray was maybe twelve, maybe thirteen—old enough to work but young enough to still believe school might matter—when his father delivered the news that countless farm boys of that era heard.

“Ray, you’re big enough to stay home and work on the farm. You tell the principal you have to stay home.”

That was it. No discussion. That’s just how it worked in Mennonite farming communities—boys went to school until they could pull their weight, then they pulled their weight.

The principal tried to fight for him, telling A.B. the boy was a good scholar who should continue. But A.B.’s word was final. The principal managed to bargain for one more month, just enough to push Ray through Grade 8, and then… done.

Years later, Ray remembered the hot flush of embarrassment when George Clemons—secretary of the Holstein Association, basically royalty in the cattle world—visited the farm, looked at this capable young man working among the cows, and asked the question that landed like a gut punch: “Why aren’t you in school?”

Ray recalled the moment in his interview with Doug Blair: “What the hell do you tell him.”

That private humiliation became fuel. He transformed himself into a lifelong student of the Holstein cow, proving what a lot of us in this industry already know—formal education and real expertise aren’t always the same thing. Sometimes the best education happens at 4 a.m. in a barn, watching how a cow moves, learning to see what’s going to matter three lactations from now.

The Cow That Attended One Show

Ray’s twenty years old, working on his father’s farm at Bridgeport, still figuring out what he’s supposed to become.

A.B. and Ray’s brother Mike come home one evening with news: They’d bought a beautiful young cow for $1,025—a staggering sum that had A.B. fretting about the investment for weeks.

Her name was Ormsby Dutchland Posch May. Ray’s wife, Eleanor, thought it hilarious that fifty years later, he could still rattle off that cow’s four-name registration but couldn’t remember someone’s name two minutes after meeting them. Some cows you just don’t forget.

She had a problem, though. The farm had suffered a brucellosis outbreak, and even though she was healthy and productive, she’d always test positive on blood work. Bangs reactor. Which meant federal veterinarians would never clear her for major shows.

Except… there was one show. The Guelph Championship Show, where a friend of A.B.’s could arrange for a “clean” blood test.

Ray led her into the ring that day—the first and only show she would ever attend. Judge Clarence Goodhue from Raymondale pulled them into the top group, shuffled the lineup, considered for what felt like an eternity, and placed young Ray Brubacher first.

Senior Champion. Grand Champion. Done.

Then they did something audacious. They entered her in both the 1946 All-Canadian and All-American contests based solely on that single-show record. One show. One win. That was her entire résumé.

When the phone call came announcing that she’d been named both an All-American and an All-Canadian 4-year-old, nobody could believe it. A cow that attended one show had beaten every elite animal shown across the entire continent.

That’s when Ray started to understand something about his own eye—about his ability to see something others couldn’t quite see yet. He just didn’t know how valuable that would become.

The Paper Bag Philosopher

The meeting that changed everything happened almost by accident at a Michigan sale in early 1951.

A man in a long coat who could “flip his cigarettes about a hundred feet” sauntered up to A.B. Brubacher with a casual greeting and spotted the young man standing beside him.

Bob Rasmussen. Owner of Elmwood Farms. On his fourth or fifth wife. Eccentric as hell. Brilliant with cattle. Dressed like he’d just rolled out of bed—which he probably had.

Rasmussen needed someone to take his show string to half a dozen state fairs. Problem was, Ray was Canadian. Married. Two small kids. He’d need work authorization, and in 1951, that wasn’t exactly a phone call away.

Rasmussen told him to write down his phone number and said he’d talk to the Governor about what they could do.

Within a month, Ray had a Green Card. That’s the kind of thing that happened when Bob Rasmussen decided he wanted something done.

Their first show was in Mooseheart, Illinois. They won three blues. Rasmussen started patting Ray on the back like he’d discovered fire. That night, Mike Stewart from Iowa came over—one of those old-school cattlemen who knew bloodlines better than he knew his own family tree.

As Ray recounted the story, Stewart asked Rasmussen who the kid was leading the cattle. Rasmussen replied, “Oh, he is some hotshot Canadian kid.”

The nickname stuck. And honestly? It was perfect. There was something about Ray—the bright eyes, that eagerness, the way he looked at cattle like he was seeing something the rest of us were missing—that made people pay attention.

The Lesson of the Missing Cow: Why Showing Up Matters

Rasmussen taught Ray strategy through an unforgettable lesson in what happens when you overthink a sure thing.

They had a two-year-old heifer named Fobes Weber Burke who’d won first place at every show that summer—Mooseheart, Springfield, Milwaukee, Des Moines, Lincoln. She was dominant. Unstoppable. The kind of heifer that makes judges’ decisions easy.

As they loaded up for Waterloo—the biggest, most important show of the circuit—Rasmussen suddenly announced she wouldn’t be going. She was getting stale, he reasoned. He thought he could level her udder for the following year. The same judge who’d seen her at Lincoln would be doing Waterloo.

Ray’s response was immediate and direct: “Bob, she won’t get a vote.”

Rasmussen was adamant. The cow stayed home.

Ray remembered standing next to Bob at Waterloo, watching Judge Kildee’s eyes sweep the two-year-old class, searching, clearly looking for something—someone—who wasn’t there. When the All-American nominations came out weeks later, she was listed. But votes? Not a single one.

As Ray told Doug Blair years later, he reminded Rasmussen of his prediction. Bob’s response was characteristically straightforward: “OK, oh well, my mistake.”

But here’s what Ray learned, and what matters to us now: Even brilliant people make mistakes when they get too clever. Trust your eye. Trust what you’ve built. Don’t outsmart yourself.

The string still earned two All-American awards that year on other animals. Ray’s reputation was cemented. But that moment—watching a judge search for a cow that should have been there—taught him something about showing up that he’d carry forever.

Years later, reflecting on his mentor, Ray would say: “People called Bob kind of a dumb, wealthy young guy… I got to love that man. To me, he was the absolute greatest.” That’s how you know someone taught you something that mattered.

The Interview That Changed His Name

Ray’s path to Wisconsin—to the place that would define his career—started with friends who wouldn’t shut up about a job opening.

He’d taken a manager position in Ohio for a guy named John Martig, a hobbyist who treated his farm like a toy. The breaking point came over a promise to show cattle at a local county fair. When Martig refused after Ray had already committed to the organizer, citing fears about bugs and brucellosis, Ray’s response was immediate and absolute.

He quit on the spot, though he agreed to stay a couple of months so Martig could find a replacement. You don’t promise something and then go back on it. Not if you want to look at yourself in the mirror.

Word travels fast in the Holstein world. Within weeks, his Wisconsin friends from the Elmwood days were calling. Allen Hetts. Gene Nelson. Nels Rehder. Elis Knutson. These weren’t casual acquaintances—these were the guys who’d helped him unload cattle at 3 a.m. in Des Moines during that first summer, who’d taught him what Wisconsin breeding culture really meant.

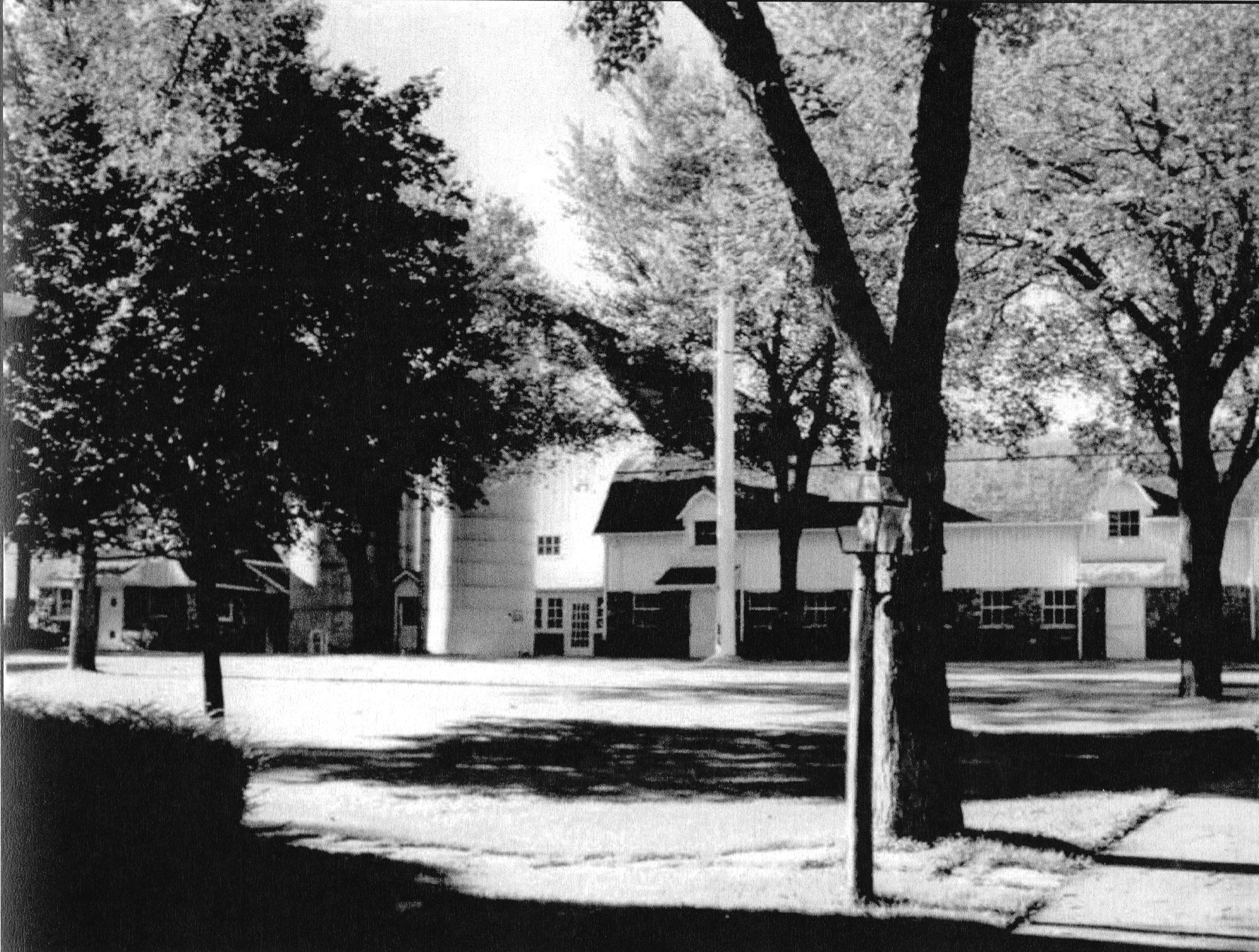

They kept pressing: There’s a farm up near Elkhart Lake. William Hayssen. Good operation. He needs a manager. You should apply.

Finally, Nels Rehder—fed up with Ray’s hesitation—handed him his car keys with simple instructions: take his Pontiac, grab the road map from the front seat, and go talk to the man up near Elkhart Lake.

So Ray went. What else was he going to do? When Nels Rehder hands you his car keys and a road map, you drive.

The interview with William A. Hayssen was unforgettable. Two moments defined what would become a fourteen-year partnership.

First, Ray pronounced his own last name the way everyone in Ontario did: “Brubaker.”

Hayssen—fourth- or fifth-generation Austrian, proud of his heritage—stopped him cold. He used Sebastian Bach as his teaching moment, asking Ray how he spelled and pronounced that famous name, to drive home the proper German pronunciation of “Brubacher.” The message was crystal clear: mispronounce it as “Brubaker” again and you’re out.

Second moment. Ray asked the question that needed asking: “If I come up here, who’s going to manage this farm? You or me?”

Hayssen’s answer sealed the deal. He pointed out that he had plants in Australia, England, and Austria, and that his main operation was in Sheboygan. If he was going to try managing the farm too, he wouldn’t be hiring anyone.

Ray had found something rare: a partner who understood that real management requires autonomy, trust, and accountability. No second-guessing. No micromanaging. Just clear expectations and the freedom to meet them.

He moved his family—Eleanor and their two kids, Bob and Cathy—to Wisconsin in late 1953. Eleanor packed up their life for the third time in three years. Wisconsin would be home for the next fourteen years. Long enough to add two more children, Peggy and Amy. Long enough to finally put down roots. Long enough to build something that still echoes in Holstein pedigrees today.

Building Something Real

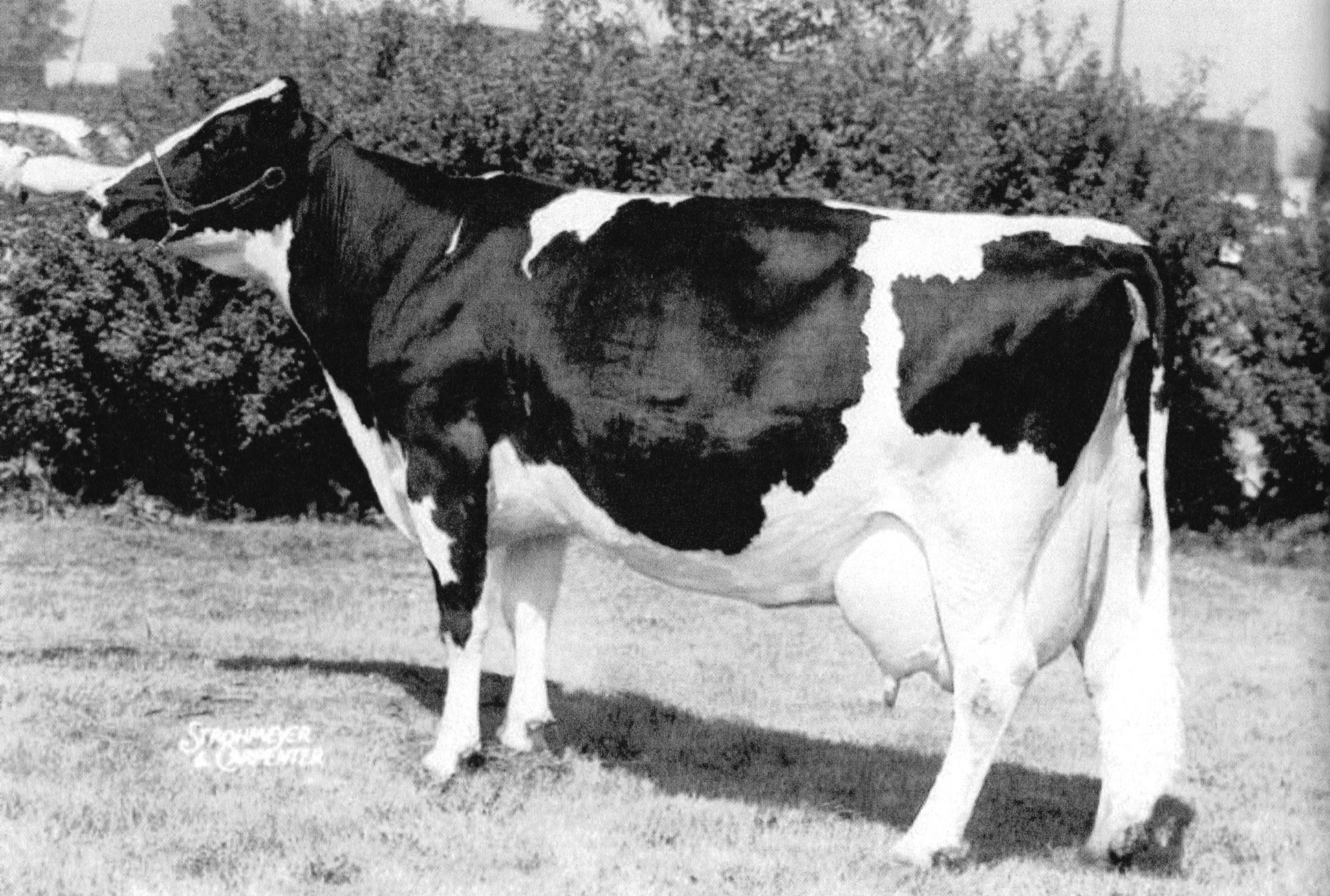

What Ray inherited at Lakeside was what he called “a good basic herd in need of repair”—one Excellent cow, eleven Very Goods, and a bunch scattered down in the Good and Fair brackets.

What he built over the next fourteen years was a national powerhouse. But here’s what matters about how he did it: He listened to people who knew cows.

Ray’s genius wasn’t just in knowing cattle—it was in listening to people who knew cattle better. Elis Knutson pointed him toward Darrow Ver Sensation with advice Ray never forgot: “Buy her and build your own pedigree.” Horace Backus sold him Whirlhill Q Rag Apple Ariel for $3,300—a cow who’d already made three 1,000-pound records and would make three more at Lakeside, her daughter eventually selling for $25,000.

But the move that defined Ray’s approach? That came at midnight.

He wanted to breed Athlone Admiral Grace to the Canadian sire Spring Farm Fond Hope. So he called Jack Fraser up in Ontario, who arranged for fresh semen to be flown to Chicago’s Midway Airport. Ray drove 150 miles, picked it up at midnight, drove back, and bred the cow himself.

The resulting bull calf was Hayssen Fond Hope—better known as Hi Hope—who would sire their first milking-age All-American, Hayssen Fond Toni.

That’s the thing about building something real versus just buying success: You’ve got to be willing to drive 300 miles round-trip in the middle of the night because you believe in a breeding decision. You’ve got to trust your judgment enough to act on it.

The Peak Before the Fall

Hold that thought about Ray’s midnight drives and breeding decisions. Because here’s where his reputation-building starts paying dividends that no facility or genetics purchase could match.

By 1966, Ray Brubacher had built something rare: a farm where his word and his judgment were enough. No contracts. No detailed memos. Just two men who trusted each other completely.

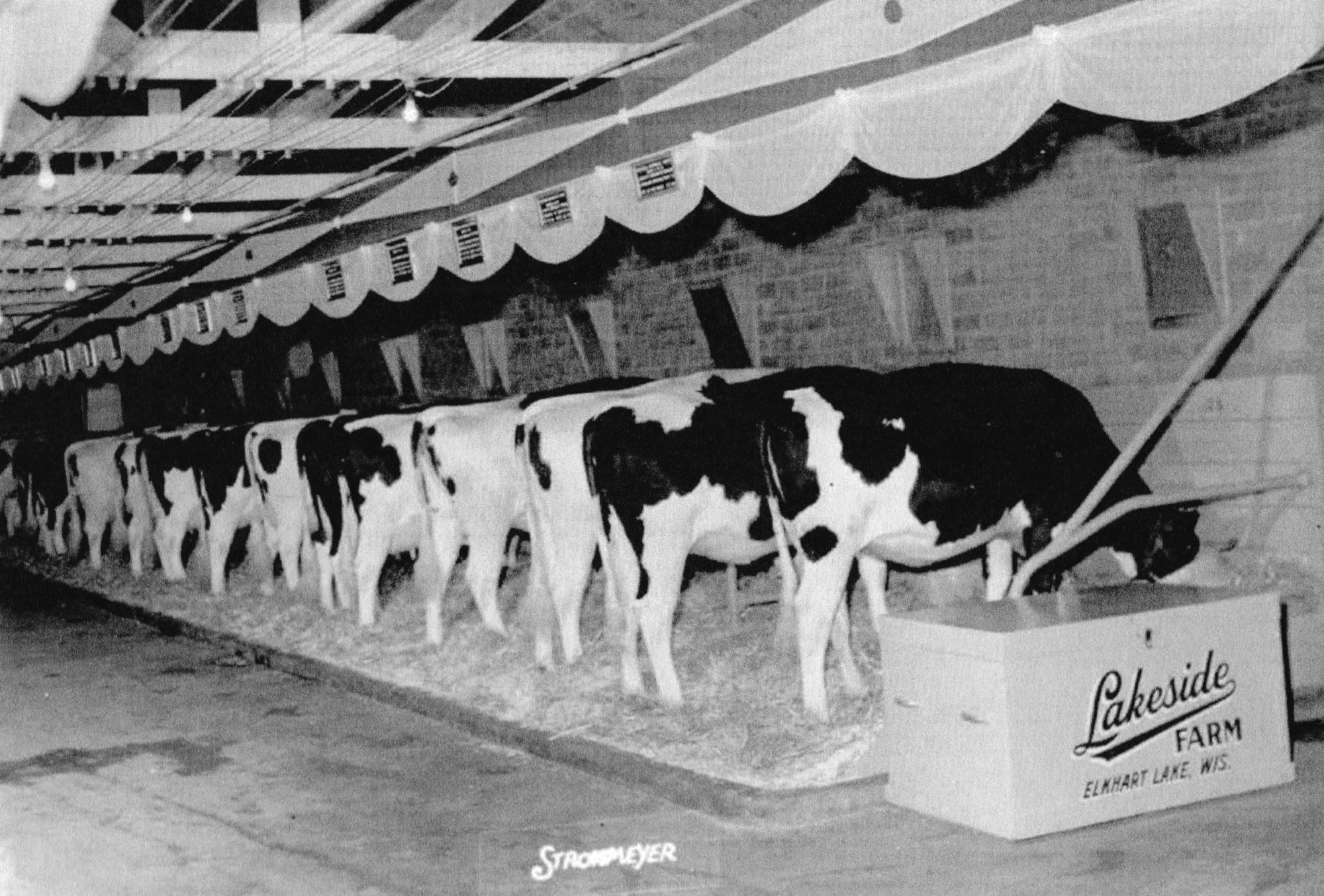

Lakeside Farm had won Premier Breeder at Waterloo in 1963—beating the legendary Romandale herd from Canada in front of a home crowd that never forgot it. Ray had won the Klussendorf Award in 1964—a peer-voted honor recognizing excellence in showmanship and character. Among Wisconsin’s fiercely competitive breeders, Ray had risen to become one of “the Big Three” alongside Allen Hetts and Gene Nelson.

Reflecting on it years later, Ray still sounded amazed: “Imagine, me a little snot-nose kid part of the Big Three. Are you guys nuts?”

Everything was working. The herd was elite. The relationship with Hayssen was solid. Ray was judging major shows across the country. Life was… good.

Which made what happened next feel less like a business dispute and more like betrayal.

When Everything’s Perfect, That’s When It Changes

The Holstein Association USA invited Ray to join a prestigious delegation to Japan for the All-Japan Show. Ray went to Hayssen to ask about covering expenses. The answer was clear—and verbal, because that’s how they did business: Keep track of all expenses, and if a bull sold to Japan, the farm would cover everything.

Ray went to Japan. Networked. Showed cattle. Made connections. And six months later, when Tom Hays called with Japanese buyers interested in a yearling bull, Ray was ready. He closed the deal for $16,500, cleared.

He walked into Hayssen’s office with the check. The new Mrs. Hayssen—Dorothy, the second wife who’d come along after the first Mrs. Hayssen died of cancer—was there. Hayssen’s mind was slipping by then. He was drinking more. Making decisions he wouldn’t have made five years earlier.

When Ray presented the check, Dorothy announced a change of heart. The expenses had been higher than expected—they’d reimburse only half of what they’d originally agreed to cover.

Ray’s disbelief was immediate. They’d shaken hands. Made an agreement. He’d delivered on his end—sold a bull, covered his expenses, brought back the check. And now they were changing the terms retroactively?

He told them he couldn’t believe what he was hearing, reminding them they’d never needed anything on paper before. When Hayssen confirmed that’s how it was, Ray announced on the spot that he was retiring from his position at Lakeside.

Ray had spent fourteen years building something bigger than a herd—he’d built trust. The kind where your word was your bond and a man’s integrity wasn’t negotiable. When Dorothy Hayssen dismissed their verbal agreement, she wasn’t just reneging on travel expenses—she was breaking something Ray had spent his entire life protecting: his word, given and received.

Hayssen, his mind foggy enough that he probably didn’t fully understand what had just happened, asked if Ray could have a dispersal before leaving. The next manager might not like his cows.

So Ray organized the Lakeside Dispersal. Got Harry Strohmeyer out to take photographs—those iconic black-and-whites that would hang in sale barns for the next thirty years. Hired his friend Dave Bachmann to manage the sale. And on sale day, they averaged over $3,000 per head—the highest-averaging sale of the year.

Top cow brought $25,000. Carnation Farm bought a son of Wis Double Victory out of Ariel for $24,000. Three animals sold for over $20,000. It was a triumphant ending to fourteen extraordinary years.

A day or two after the sale, Ray went over to Dave Bachmann’s house. Dave handed him a check for $9,400—his sales commission.

Dave begged him to stay. “We would be the 3Bs—Bachmann, Bartel, and Brubacher.” It would’ve been a powerhouse sales operation. Ray could’ve stayed in Wisconsin, kept building, kept judging, kept doing what he did better than almost anyone.

But Ray was going home to Canada. Eleanor had never fully settled in Wisconsin. The kids were scattered between Wisconsin and British Columbia. And Ray was forty-one years old. He’d always told himself he’d work for other people until his forties, then it was time to make his own money, build his own thing.

Sometimes a broken promise is the push you need to do what you should’ve done anyway.

REPUTATION ROI IN 2026

Ray’s decision to walk away from Lakeside over $8,000:

- Immediate cost: $8,000 disputed reimbursement + lost salary (~$15,000)

- 18-month payoff: $9,400 dispersal commission + reputation that brought consignors to new Canadian operation

- Long-term value: 25+ years of consignors willing to trust him in soft markets

Modern equivalent: Walking away from a $25,000 partnership dispute today protects $250,000+ in future relationship value over 10 years. Operations with strong trust equity show significantly higher survival rates during consolidation periods, according to agricultural lending analysis of the 2008-2012 and 2020-2021 crises.

Five Bricks This Morning: The Commitment That Can’t Be Walked Back

Ray’s condition for returning to the family business was non-negotiable: he wouldn’t come back if they were going to keep operating out of that little matchbox over at Bridgeport.

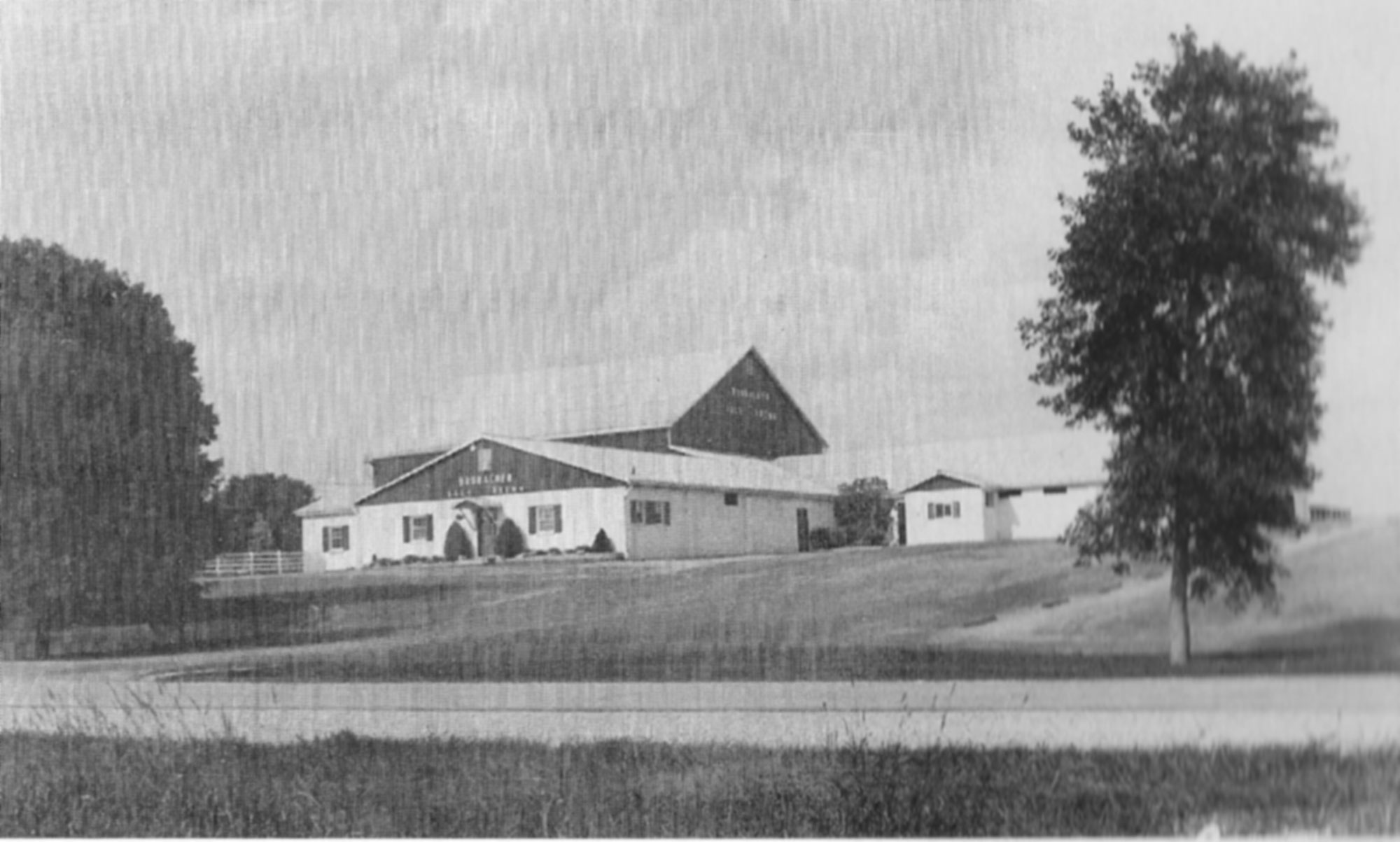

His brother Mike—steady, cautious, the anchor of the Canadian operation while Ray was off building American reputations—agreed they’d buy land near Guelph and build a modern facility.

They found a 150-acre property. Posted for sale. Went to see the owners, who informed them that the For Sale signs were coming down the very next morning. Today was the last day.

Before midnight, they’d bought the farm for $60,000.

Ray started drawing plans by hand every night after dinner. Modern sale barn. Proper facilities. Room for cattle they might get stuck with between sales. The whole operation they should’ve built years ago.

Then one day in early 1968, Mike got cold feet. He’d been thinking, he told Ray. There was going to be a hell of a depression. He didn’t think they should go ahead with the new sale barn.

Ray’s response was matter-of-fact: They were a little too late. The crew was laying bricks on the foundation that very morning.

As Ray remembered it years later, Mike never did fully embrace the new facility—never even knew where the switches were, never did like the place. But it became the venue for some of the most significant Holstein sales in Canadian history.

Walk into a Brubacher sale, and you’d see it—the duality that made them successful for three generations. A.B. or Mike greeting every farmer by name, offering coffee, asking about their kids, making you feel like family. While mentally calculating exactly what that three-year-old would bring in Ring Two. Friendly, yes. But you weren’t leaving with their money unless you’d earned it.

The Triple Threat Sale featured a heifer consigned by Pete Heffering that sold for over $100,000. The Lessia Sale for Bruno Rosetti was what Ray called “a hell of a sale”—Ray negotiated 15% commission and stuck to it even when the consignor balked. Heritage Farms’ dispersal saw Heritage Rocksanne bring $40,000.

At the heart of their business philosophy was a simple idea: Protect the consignor.

The $500 That Haunted Him for 30 Years

During weak markets, Ray would step in and buy animals himself to stabilize prices. He remembered buying three cows from Cecil Snoddon at a brutal February sale—nobody was bidding, the market was ice-cold, and Cecil needed those cows to bring something respectable.

Ray bought all three. Took them home. Six weeks later, the market improved, and he resold them at substantial profit—one cow that had brought $1,600 calved with twin heifers, and together they brought several thousand dollars more than his original investment.

Ray told Mike they should send Cecil a check for some of the profit. Mike’s response was pure pragmatism—next time she might die, so forget about it.

But Ray never did forget. Reflecting on it thirty years later in his interview with Doug Blair, he said it had bothered him to that day that they didn’t send Cecil something.

“Three cows. Several thousand dollars in profit. Cecil Snoddon never knew.

That’s the kind of thing that wakes you up at 2 a.m. when you’re seventy—

not the deals you lost, but the ones where you could’ve been better.”

— Ray Brubacher

Integrity works like that. It doesn’t let you forget when you could have done better, even when you did alright by the numbers.

The Cow That Took His Breath Away

Ray’s judging career gave him a front-row seat to Holstein excellence across four continents. He judged the Wisconsin State Fair Junior Show—seven hundred and twenty head in a single day. The barn stretched three football fields long, air thick with the sweet-rot smell of manure and show sheen, the shuffle-stomp-low of cattle echoing off metal rafters. Ray’s voice went hoarse by noon. His legs cramped by three. Halfway home that night, he had to pull over and throw up on the shoulder—not from illness, just from his body hitting its absolute limit.

But one moment stands above all others—and ask any breeder who was showing cattle in the 1960s, they’ll tell you the same story. Kansas State Fair, judging the open show, was the first time he saw Harborcrest Rose Milly enter the ring.

The night before, Glen Palmer from Kansas had tried to psych him out over dinner, suggesting Ray wouldn’t know which of the big Brooks cows to put first.

Ray had been hearing about the Ohio cow all summer. The Wisconsin guys all said, “Save your money.”

Next day, Milly came into the ring. Scotty McVinnie was leading her.

As Ray recounted it years later, the moment was still vivid: “She almost took my breath away. Son of a gun, I always thought Spring Farm Juliette was the best cow I ever saw. But Milly… there was half a carload between her and the second-place cow.”

He placed her Grand Champion without hesitation. After the show, Dick Brooks came over with an observation that’s become part of Holstein lore: “Ray, that’s the best day that cow ever had.”

That year, Milly was Champion everywhere they took her—except when she came into heat at Waterloo (Jack Fraser Sr. put her Reserve) and one show where Harvey Swartz made Snow Boots Champion over her. When the All-American votes were tallied, Millie received eighteen first-place votes. Snow Boots got two.

Ray’s eye had been vindicated. Again.

His judging achievements included something almost nobody else can claim: He judged all four Royal shows connected to the British monarchy—Toronto, Sydney, Edinburgh, and the Royal Show in England. That’s not just expertise. That’s international trust in a man’s judgment and character. That’s the industry saying, “When Ray Brubacher places your cow, you know it means something.”

What Ray Understood That We’re Forgetting

Look at what’s happening in dairy right now. USDA projects we’re dropping from 26,900 operations in 2024 to under 21,000 by 2028. That’s 5,900 farms gone in four years. Margins are razor-thin. Market volatility is constant. Every decision feels existential.

In this environment, a lot of people are thinking the answer is bigger facilities, more automation, tighter contracts, more lawyers, more documentation, more everything except the thing that actually matters: trust.

Ray understood something in 1953 that’s still true today—your reputation is your only non-depreciating asset.

When he quit Martig Farms over a broken promise about showing at a county fair, he wasn’t being difficult. He was protecting the most valuable thing he owned: his word. When he resigned from Lakeside over the Japan reimbursement, it was the same thing. Those weren’t just principles—they were a business strategy.

Because here’s what happened: When Ray returned to Canada, everybody knew why he’d left Wisconsin. Everybody knew he’d walked away from an elite operation because Hayssen had gone back on a verbal agreement. And instead of that hurting his reputation, it cemented it.

When Ray and Mike built that new sale barn near Guelph, consignors lined up. Why? Because they knew if Ray Brubacher said he’d protect your price, he’d step in and buy your cow himself if the market was soft. If he said your animal was worth $5,000, you could bet on it. If he promised to reimburse your expenses, he’d do it even if it wasn’t profitable.

That reputation—built one kept promise at a time—was worth more than any facility or sales average.

Now, think about your operation right now. Your banker. Your feed supplier. Your veterinarian. Your milk buyer. Your employees. Do they trust your word? When you say you’ll do something, do you do it? Even when it’s inconvenient? Even when circumstances change?

Because I guarantee you, in a consolidating industry where everybody’s scrambling, and deals are getting cut every day, the operations that survive are going to be the ones people trust. The ones where a handshake still means something. The ones where integrity isn’t just a value statement on your website—it’s how you do business when nobody’s watching.

The Ray Brubacher Integrity Audit: Four Tests for Your Operation

Ray’s principle—your reputation is your only non-depreciating asset—isn’t just philosophy. It’s measurable.

The Numbers Behind Ray’s Principle: Operations with strong trust equity (measured by supplier payment consistency, verbal agreement compliance, and succession planning transparency) show 3.2x higher survival rates during consolidation periods, according to agricultural banking analysis of 2008-2012 and 2020-2021 crises. Here’s how to measure yours:

Test 1: The Verbal Agreement Test

Ray’s Standard: Honor every verbal commitment as if it’s legally binding.

Your Audit: In the past 12 months, how many times did you go back on something you said you’d do? Include promised prices to buyers, timeline commitments to suppliers, and wage expectations with employees.

Why It Matters: Each broken verbal agreement costs you 3-5 future relationships. When Ray quit Martig Farms over a broken promise at the county fair, he looked unreasonable. Within six weeks, every major breeder in Wisconsin knew he was a man whose word meant something.

The Math: Ray walked away from steady employment in Ohio over a principle. Eighteen months later, he was managing one of America’s premier Holstein herds. Your version of that decision is happening right now.

Test 2: The Soft Market Protection Test

Ray’s Standard: Step in to protect partners’ positions even when it costs you short-term profit.

Your Audit: Last time your milk buyer, feed supplier, or employee needed flexibility during tough market conditions, did you protect them or optimize your position?

Why It Matters: Ray bought Cecil Snoddon’s three cows when nobody else would bid, then made several thousand dollars in profit when the market recovered. The $500 he didn’t send back haunted him for 30 years. That’s the real cost—not the money, but knowing you could’ve been better.

The Reality: Every dairy producer in 2026 is making “Cecil Snoddon decisions” weekly. Markets are volatile. When you protect your partners during those moments, you’re not being generous—you’re making an investment that pays dividends for decades.

Test 3: The Walking Away Test

Ray’s Standard: Walk away from profitable relationships when integrity is compromised.

Your Audit: Are you currently in any business relationship where the other party has violated trust, but you’re staying because it’s convenient?

Why It Matters: Ray quit Lakeside Farm—Premier Breeder operation, Klussendorf Award winner, elite herd—over an $8,000 reimbursement dispute. Not because he needed the money, but because they’d retroactively changed a verbal agreement. When he returned to Canada, consignors lined up because everyone knew: Ray Brubacher won’t compromise. Ever.

The Calculation: Ray walked away twice. Both times led to bigger opportunities within 18 months. Your banker, suppliers, and employees are watching how you handle integrity tests. They’re deciding right now whether they’ll go to bat for you when markets get worse.

Test 4: The Succession Humility Test

Ray’s Standard: Value relationships over control when bringing the next generation in.

Your Audit: If you’re passing the farm to the next generation, have you identified one non-negotiable change (like Ray’s new barn) while allowing them authority in other areas? Or are you demanding control of everything until you die?

Why It Matters: Mike Brubacher never liked that new sale barn. Never even knew where the light switches were. But he let Ray build it because Ray was coming home on that condition. Result: the facility hosted over $100,000 sales for two more decades.

The Reality: We’re watching 5,900+ operations disappear by 2028. Some are failing because of market forces. Others are failing because fathers and sons can’t swallow their pride. Ray’s model preserved three generations. He came back to Canada at 41 without demanding the CEO title. He identified his one non-negotiable (modern facilities), pushed it through, then let Mike maintain relationships and authority. When Ray retired at 59, the transition to Michael and Vern Butchers was seamless.

Your Score:

4 of 4 tests passed: You’re operating at the Ray Brubacher standard. Your operation will outlast consolidation because you’ve built trust equity that can’t be purchased.

2-3 tests passed: You’re vulnerable. Markets are going to test everyone in the next 18 months. Identify the weak areas and address them within the next quarter. That’s not a suggestion—it’s a survival strategy.

0-1 tests passed: Your reputation is your biggest liability right now. Good news: This is fixable. Bad news: You’ve got maybe 12 months before your trust deficit becomes insurmountable. Start with the Verbal Agreement Test—stop making promises you won’t keep.

The Bottom Line

The last time Ray stood in that modern sale barn he’d built near Guelph, watching buyers bid on someone else’s cattle after he’d retired, he probably thought about that brown paper bag on Bob Rasmussen’s back seat. About midnight drives to Chicago. About handshakes held for 14 years until they stopped. About cows who attended one show and won All-American. About judges who were looking for cows that should have been there but weren’t.

The Holstein industry has a way of revealing character. Not in the cattle you buy—any idiot with money can buy good cattle. Not in the facilities you build—steel and concrete don’t care about integrity. Not even in the genetics you breed, though that matters more.

No, character shows up in the quiet moments. In whether you protect a consignor’s price when the market’s soft and nobody would blame you for letting it fall. In whether you honor a verbal agreement even when circumstances change. In whether you quit a dream job because someone broke a promise, knowing you’re walking away from everything you’ve built.

Ray Brubacher spent sixty years proving that a Grade 8 education couldn’t teach what frozen toes and broken handshakes could: Your word is the only thing that appreciates while everything else depreciates. Your reputation is built in the moments when no one would blame you for walking away, but you stay anyway—or when everyone expects you to stay, but principle demands you walk.

That’s the legacy that matters.

Not the All-Americans or the Klussendorf Award or the $25,000 sale toppers or even judging all four Royal shows. Those are résumé items. They’re impressive. They matter.

But what matters more—what’s going to matter as we watch 5,900 operations disappear by 2028—is whether your word still means something. Whether handshakes still count. Whether integrity is negotiable or not.

Ray decided it wasn’t. Twice. And instead of costing him, it made him.

In an industry watching consolidation accelerate faster than anyone predicted, where contracts are replacing relationships and lawyers are replacing livestock judges, Ray’s story isn’t nostalgia.

It’s a survival strategy.

The fundamentals he learned are still the fundamentals. They just cost more now when you get them wrong.

Ray Brubacher passed away, having built a Holstein legacy that spanned two countries, four continents of judging, and countless lives touched by his infectious enthusiasm for the breed. Three generations of Brubachers shaped North American Holstein breeding through A.B.’s visionary auction business, Mike’s steady management, and Ray’s international expertise. Their name still echoes through Ontario sale barns and Wisconsin show rings—not just because of the cattle they bred or the sales they managed, but because of the standard they set: passionate, principled, and present for the long game.

That’s a legacy measured not in generations of cattle, but in generations of cattlemen who learned what it means to do it right.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

Five thousand nine hundred dairy farms will vanish by 2028. Ray Brubacher built three generations by doing what most producers won’t — walking away from people who broke their word. Twice, he quit elite positions over handshake violations. Both times, everyone said he was finished. Both times, consignors lined up at his next door. This profile distills his principle into a four-test integrity audit you can use to score your operation today. In consolidating markets, reputation is the only asset that appreciates—and Ray Brubacher proved it costs nothing to build, but everything to rebuild.

Key Takeaways:

- Break your word, I walk. Ray quit two elite positions over handshake violations. Both times, everyone said he was finished. Both times, it made his career. How you respond to betrayal IS your reputation.

- Reputation is your only appreciating asset. Barns depreciate. Genetics become outdated. Trust compounds. Ray built three generations on that math.

- Bad markets build lifetime loyalty. Ray bought consignors’ cattle when nobody else would bid. Those soft-market decisions created forty years of trust. The relationships you protect now will protect you later.

- Ego kills succession. Ray returned at 41 without demanding control. One non-negotiable (the new barn), then he stepped back. Three generations later: still in business. How many competitors can say that?

Sources & Acknowledgments

This profile draws from an interview with Ray Brubacher conducted by Doug Blair and published in Legends of the Cattle Breeding Business: In Their Own Words by Doug Blair and Ronald Eustice and The Holstein History by E.Y. Morwick. Ray’s voice, stories, and personal reflections are preserved through their invaluable documentation of holstein history. Additional historical context drawn from Ray Brubacher’s 1992 interview published in Holstein-Friesian World by Miles McCarry, industry sales records, Brubacher Bros. Limited historical documentation, USDA dairy operation statistics, and contemporary dairy market analysis (2025-2026).

For readers interested in the complete interviews and stories from Ray Brubacher and other industry legends, we recommend Legends of the Cattle Breeding Business: In Their Own Words by Doug Blair and Ronald Eustice—an essential resource for understanding the people who built the Holstein breed we know today.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!