Teagasc and repro data show why the best herds work 19 fewer hours a week and still come out at least $24,000 ahead on a 200‑cow dairy.

Jim Kirk milks 606 Holsteins through a 60‑point GEA rotary parlour at Heanton Barton Farm near Okehampton in North Devon – and two people can run the whole thing in under two hours, according to an AHDB profile. Kirk and his herdsman Harrison handle all the AI, backed up by quarterly breeding reviews from Genus, weekly PD checks from the vet, and reports from VetIMPRESS after every visit. The team – three full‑time employees plus an apprentice, all living within five miles – meets every morning at a whiteboard, writes down the jobs, and ticks them off through the day. His pregnancy rate sits at about 25%, up from 20%, putting the herd in the top 5% of British operations on that metric.

Kirk took over from his dad and replaced an old herringbone – the kind of call you’d make if milking was eating your whole day, the AHDB profile noted. The hardware changed, sure. But the real shift was where Kirk put his own hours: breeding strategy, team development, ration management – the stuff that never happens when you’re stuck in the pit.

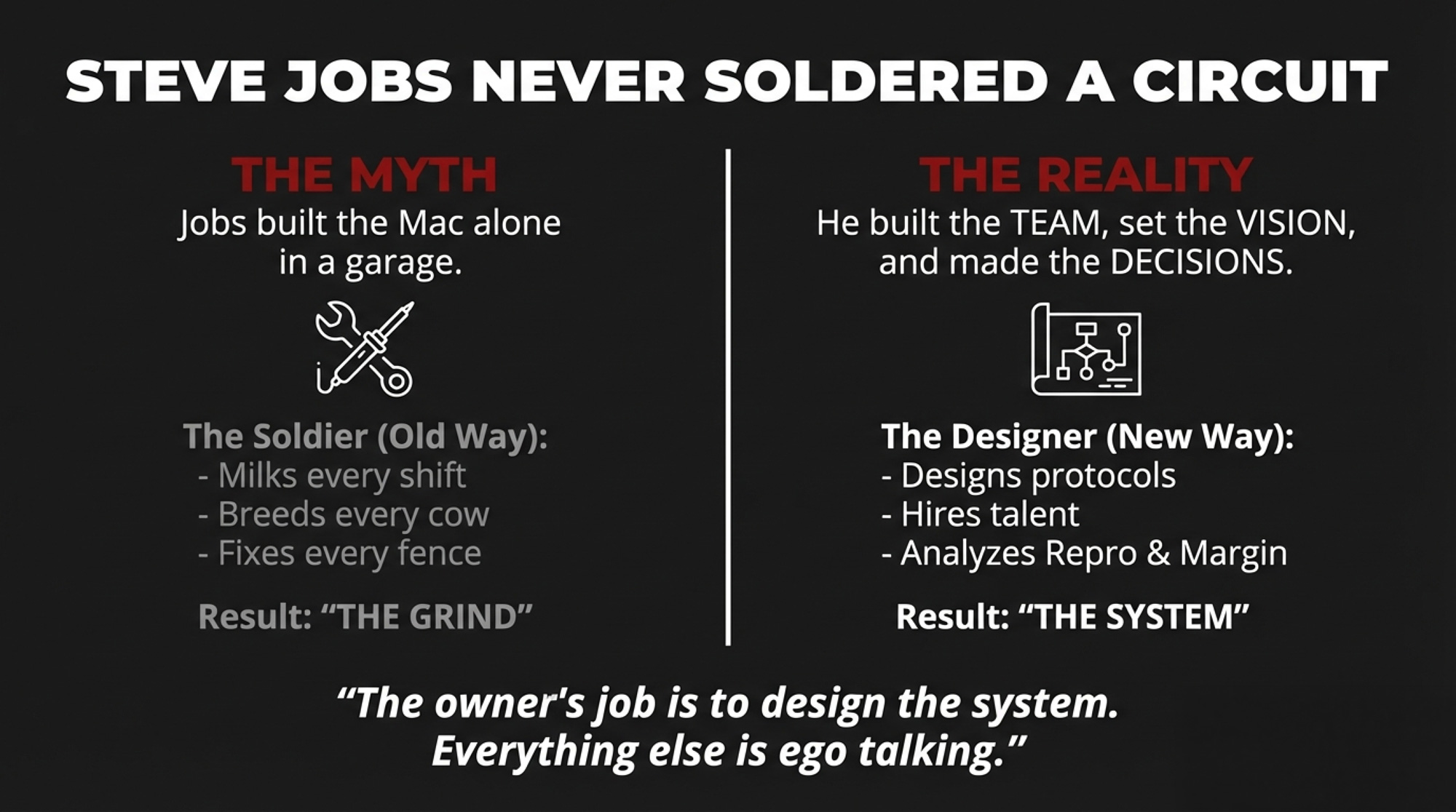

That’s the same shift Steve Jobs made on the original Macintosh – from “doer” to designer. Jobs never soldered a circuit board. He set the vision, picked the team, and killed anything that didn’t fit. The lone‑genius myth looks great on a magazine cover. It also shows up in too many barns as the lone‑wolf owner – and the gap between those two mindsets is about 19 hours a week, roughly 988 hours a year, and at least $24,000 on a 200‑cow herd before you even talk about family time.

The Steve Jobs Story We Think We Know

Most people picture Jobs in a black turtleneck, holed up in a garage, personally inventing the Macintosh by sheer force of will. Clean story. One guy. One vision. One machine.

The real story’s a lot more crowded. Jef Raskin pitched the Macintosh project inside Apple in 1979 as a cheap, easy‑to‑use computer for ordinary people. Burrell Smith – a self‑taught technician who started in Apple’s service department fixing Apple II boards – designed the first Mac prototype around Motorola’s 68000 processor. Andy Hertzfeld wrote much of the system software. Bill Atkinson built QuickDraw, the graphics engine. Jerry Manock shaped the case everyone remembers.

Jobs didn’t even join the project at the start. He spotted what the Mac team was doing, got hooked, and forced his way in around 1981. A BYTE magazine roundtable in February 1984 listed a dozen engineers and designers – Atkinson, Hertzfeld, Smith, Kenyon, Hoffman, Egner, Espinosa, Capps, Manock, Horn, Crowe – trading war stories about the machine they’d built together. Jobs sat there asking questions and drawing the line around what counted as “Mac‑like.”

What Jobs actually owned were the decisions nobody else wanted to make. He decided what the Mac would not be – not a hobbyist toy, not a business terminal, not a stripped‑down Lisa knock‑off. He picked the team, set the standard, killed features that didn’t fit the user experience, and pushed everyone to strip away anything that made the product harder to love. As quoted in that BYTE roundtable, Jobs said the team was driven by “building something really inexpensive so that everyone can afford it”.

The false lesson from that story is dangerous: if you’re the genius, you have to do everything yourself.

The real lesson is more useful on a dairy. The owner’s job is to design the system and say no ruthlessly. Everything else? That’s ego talking.

The 988‑Hour Gap Between Grinding and Growing

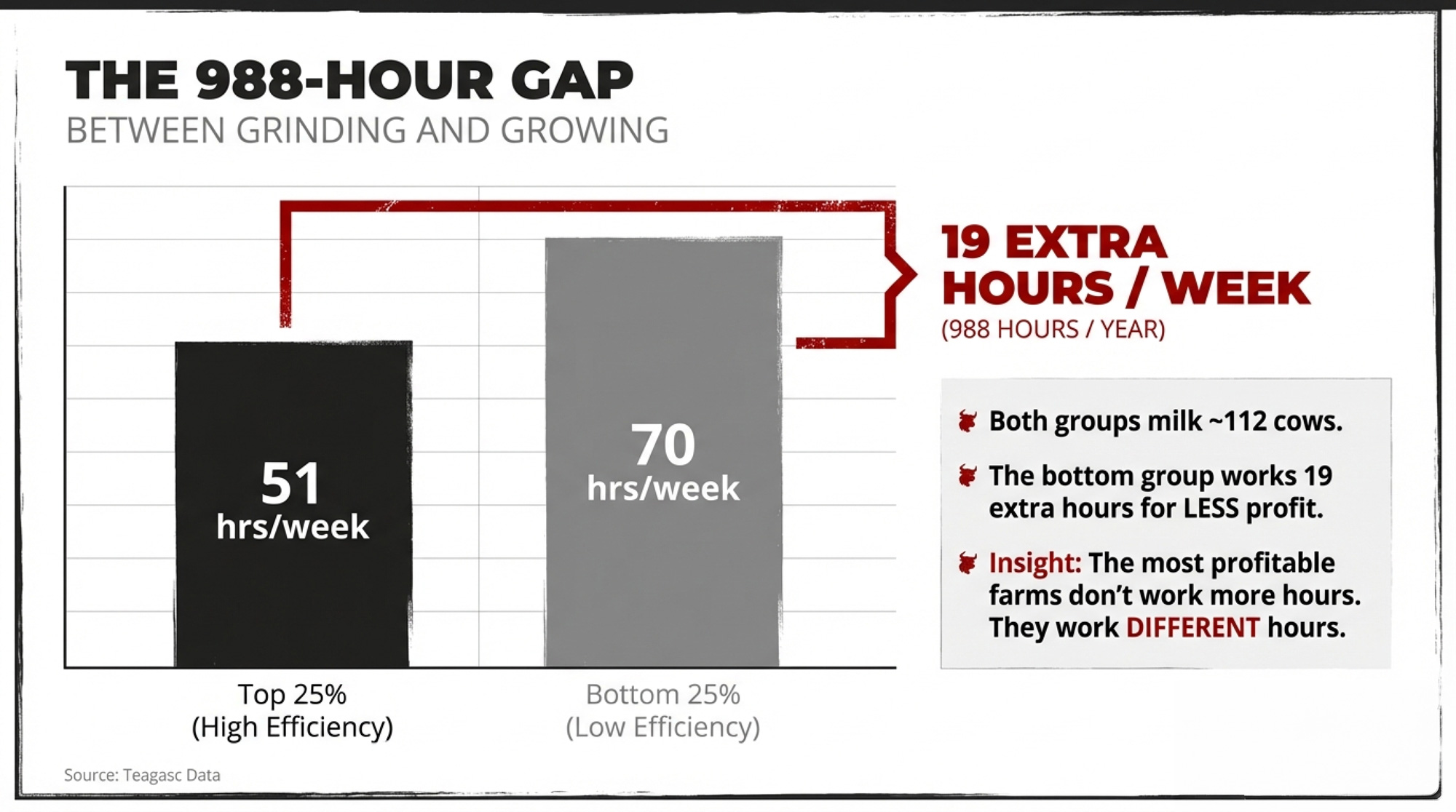

Teagasc Moorepark looked at labour time‑use on Irish pasture‑based dairy farms and split them into the top 25% most labour‑efficient and the bottom 25%. Herd sizes were almost identical – 112 cows in the top group, 113 in the bottom. The difference wasn’t cow numbers. It was hours.

On those farms, the top group worked about 51 hours a week. The least efficient worked 70. Same cows. Same grass‑based system. Nearly 19 extra hours a week for the bottom group – about 988 hours over a year.

On a seasonal‑calving Irish place, some of that gap piles up in spring when everything hits at once. But Teagasc’s case‑study work, published in the Irish Journal of Agricultural and Food Research in 2023, showed the same pattern on an individual herd: one 119‑cow spring‑calving operation ran on 2,986 total labour hours a year – about 54 hours a week – with the farmer doing 2,314 of those hours and the rest covered by family and outside help.

Those numbers are Irish, seasonal, and heavily grass‑based. Your hours will look different on year‑round calving in Quebec tie‑stalls or on robots in Minnesota. But the core finding keeps repeating whenever somebody actually measures it: the most profitable farms don’t always work more hours. They work different hours.

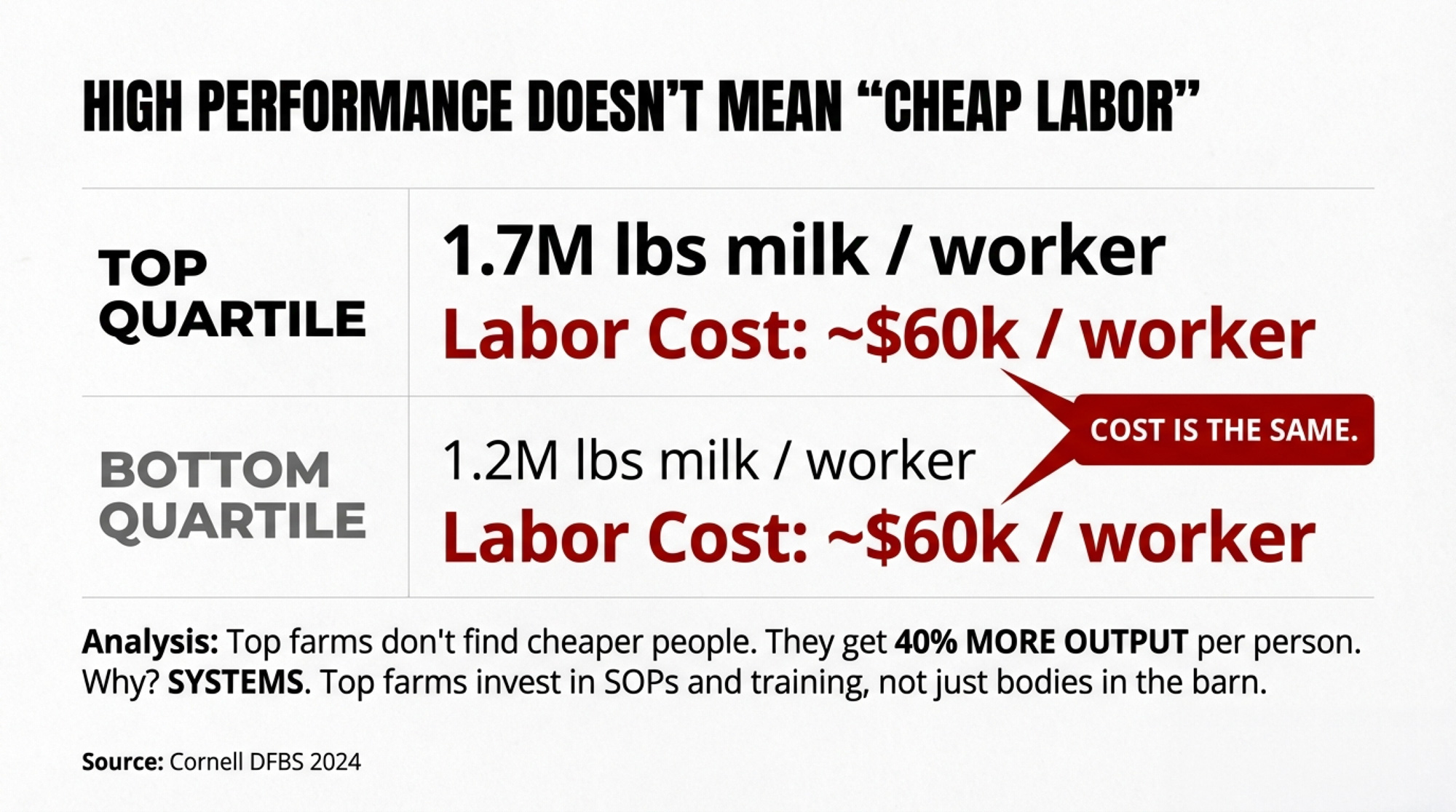

Cornell’s 2024 Dairy Farm Business Summary put teeth on that idea across 129 New York farms. Top‑earning quartile herds shipped about 1.7 million pounds of milk per worker equivalent and spent $3.17/cwt on hired labour. Bottom‑quartile farms shipped about 1.2 million pounds per worker and spent $3.82/cwt.

Here’s the kicker. Hired labour cost per worker was roughly the same across all four quartiles – between about $57,600 and $61,177 a year. Top farms didn’t find cheaper people. They got a lot more milk per person. That’s what systems do.

The Identity Problem Nobody Wants to Talk About

Jobs didn’t prove his worth by pulling every all‑nighter himself. He proved it by building a team that could ship a Mac without him standing over every keyboard.

If you’re honest, sleeping until 6:00 a.m. probably feels like failure. When you’ve been told since you were five that “real” dairy farmers are in the barn at 4:30, stepping back from a milking shift can feel like turning your back on your father’s work ethic, your cows, and half your identity.

In Teagasc focus groups, farmers themselves said “less than 55 hours per week” felt like an acceptable workload – anything above that was a grind they tolerated. Bottom‑quartile farms blew past that threshold by 15–20 hours every week. Nobody in those groups was lazy. Many had built herds from 60 cows to 200 by doing exactly what they were taught: show up first, leave last.

But the data doesn’t care how guilty you feel taking a morning off. It just measures outcomes.

The question isn’t whether the grind was necessary in 1998, when parlours were smaller and sensors didn’t exist. It’s whether the same grind is still the highest‑value use of your time when margins are tight, lenders are watching operating cost per cwt, and the technology to shift your role already sits on the market.

Every hour you spend holding a milker claw instead of managing reproduction, negotiating inputs, or reviewing cost of production is an hour you don’t get back. And once you put dollar values on those hours, the story changes fast.

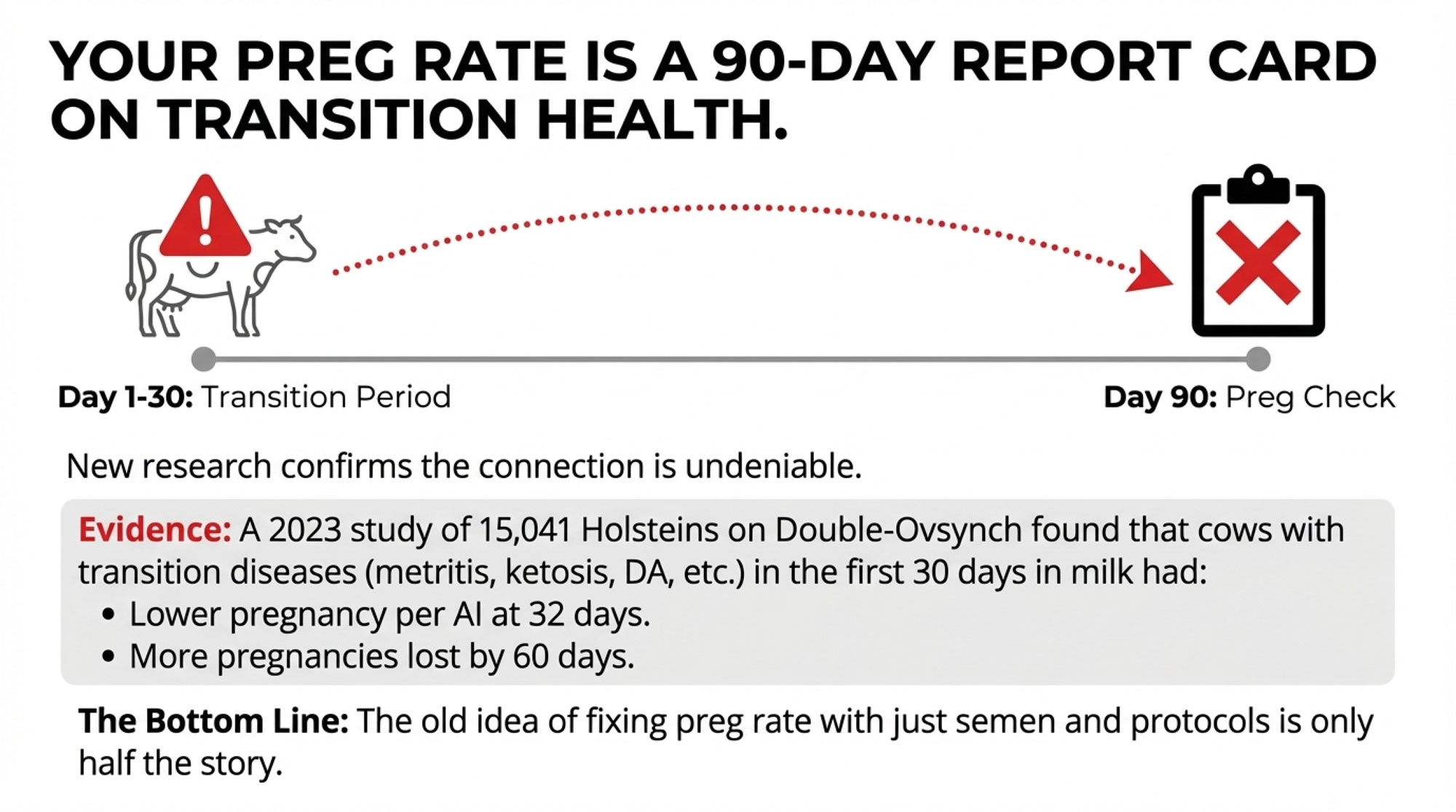

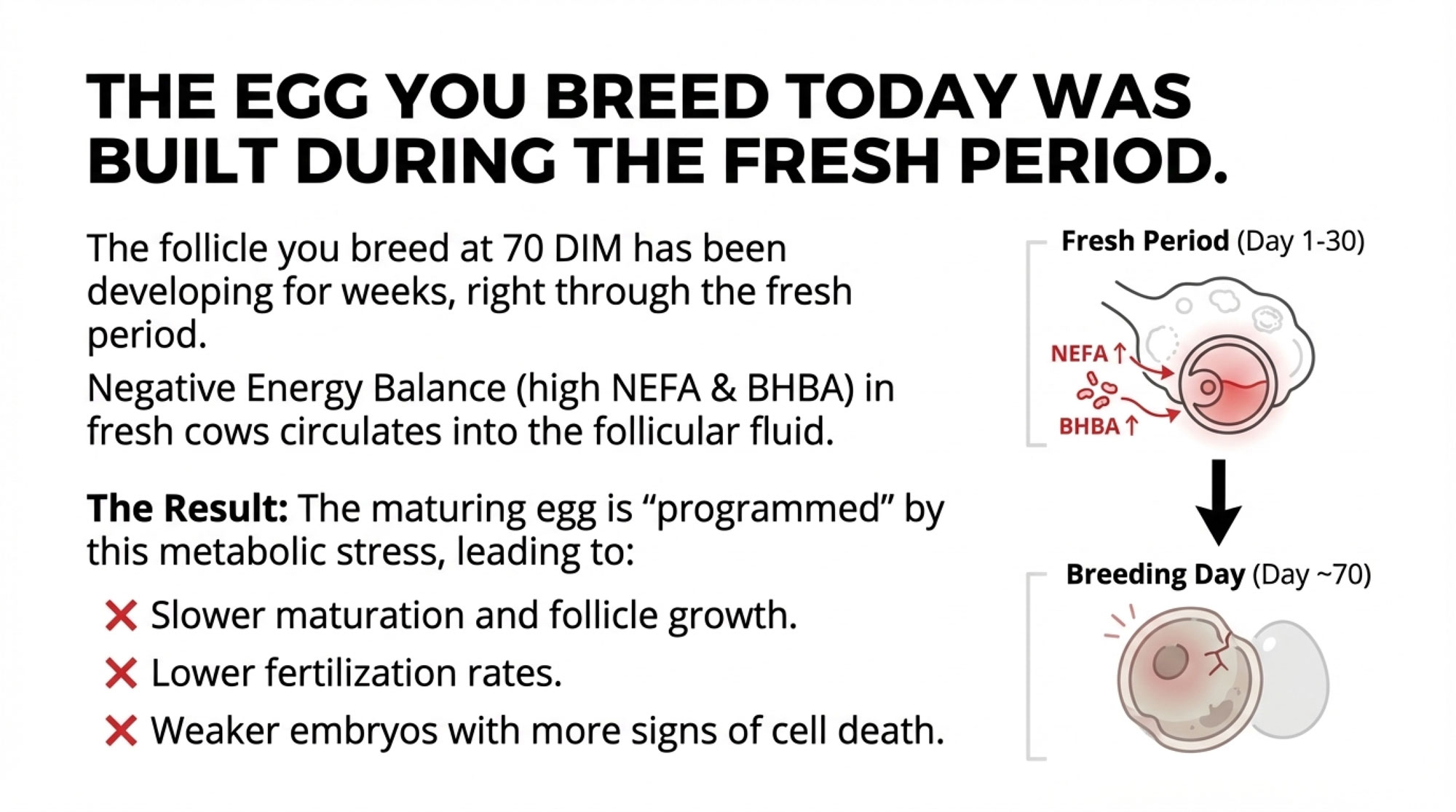

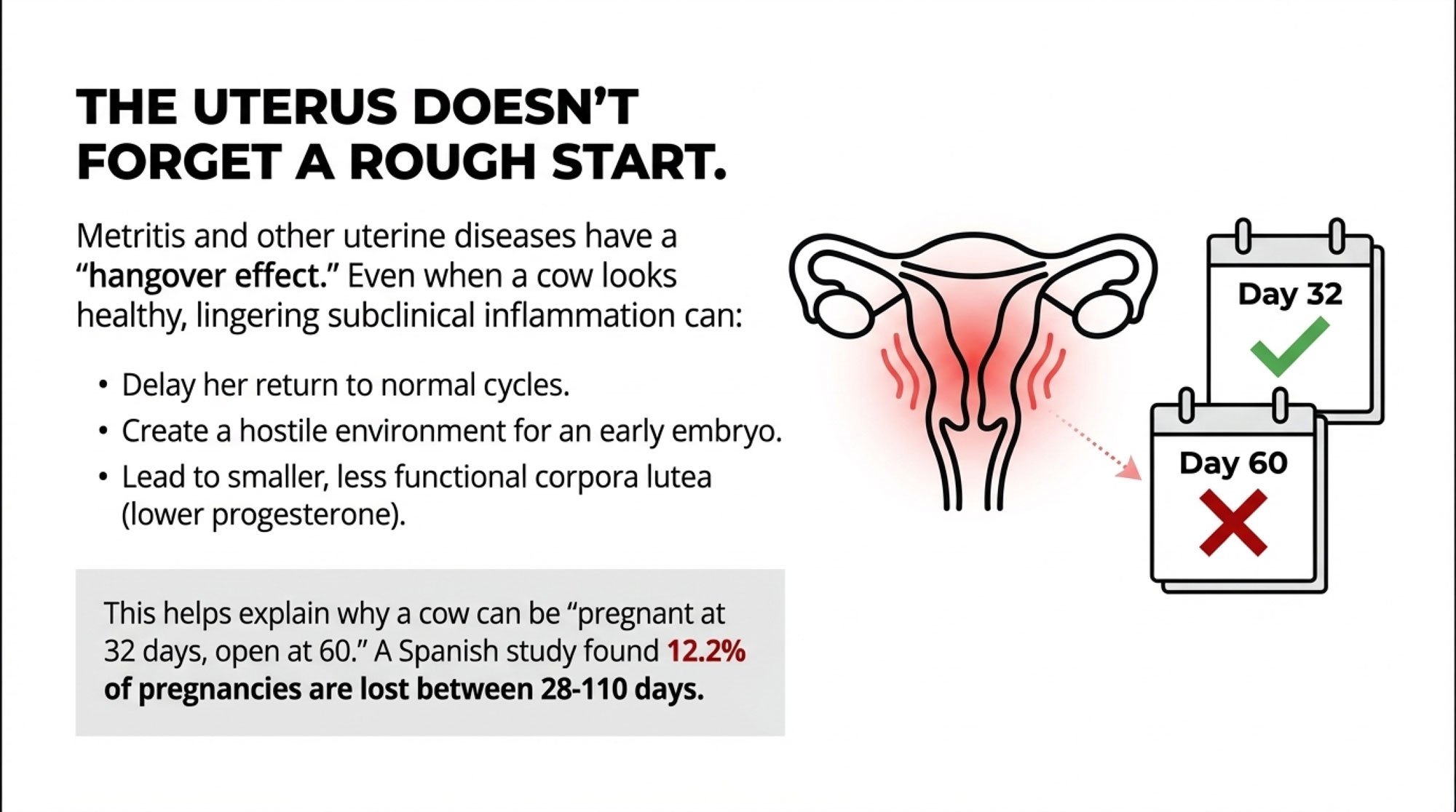

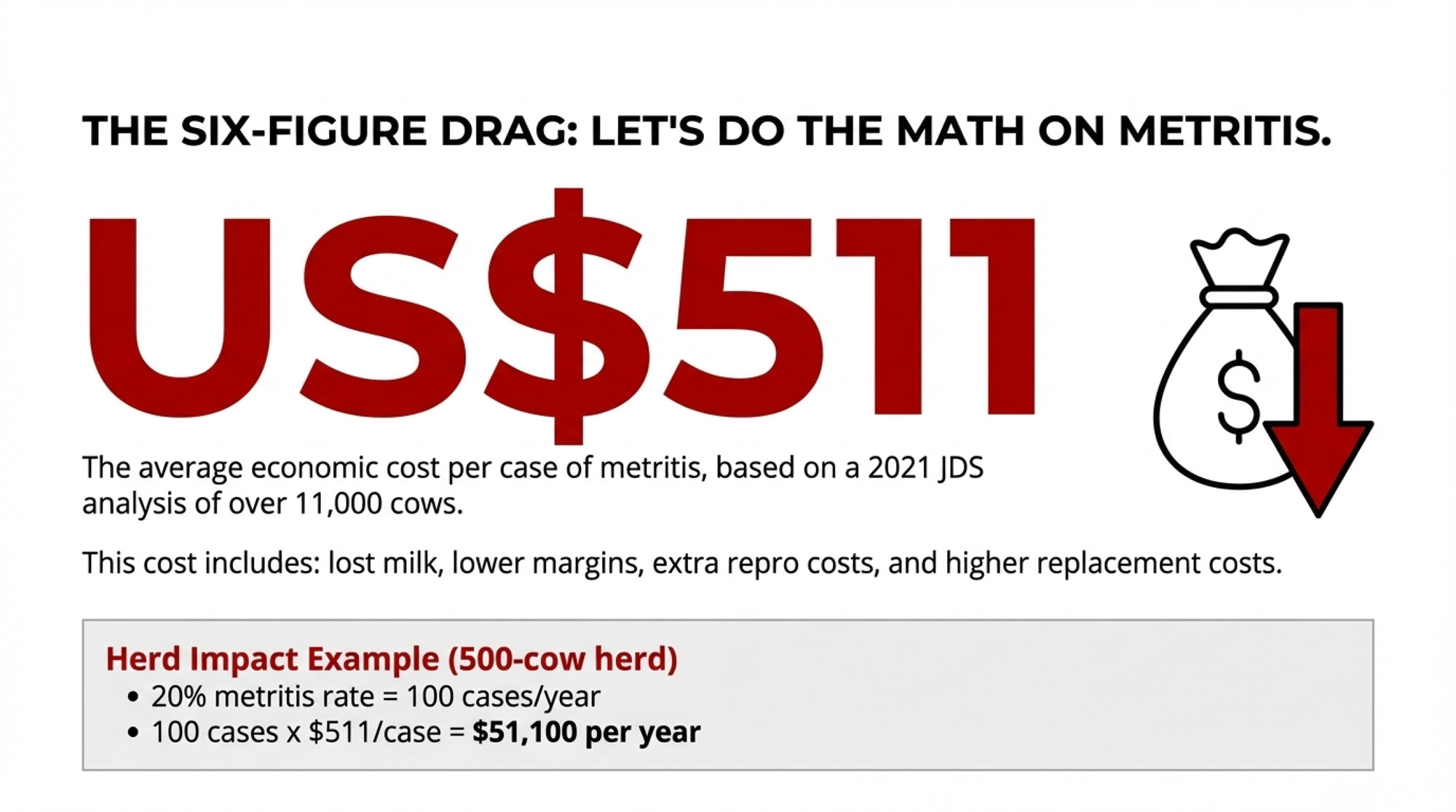

What Does a Six‑Point Pregnancy Rate Gap Actually Cost?

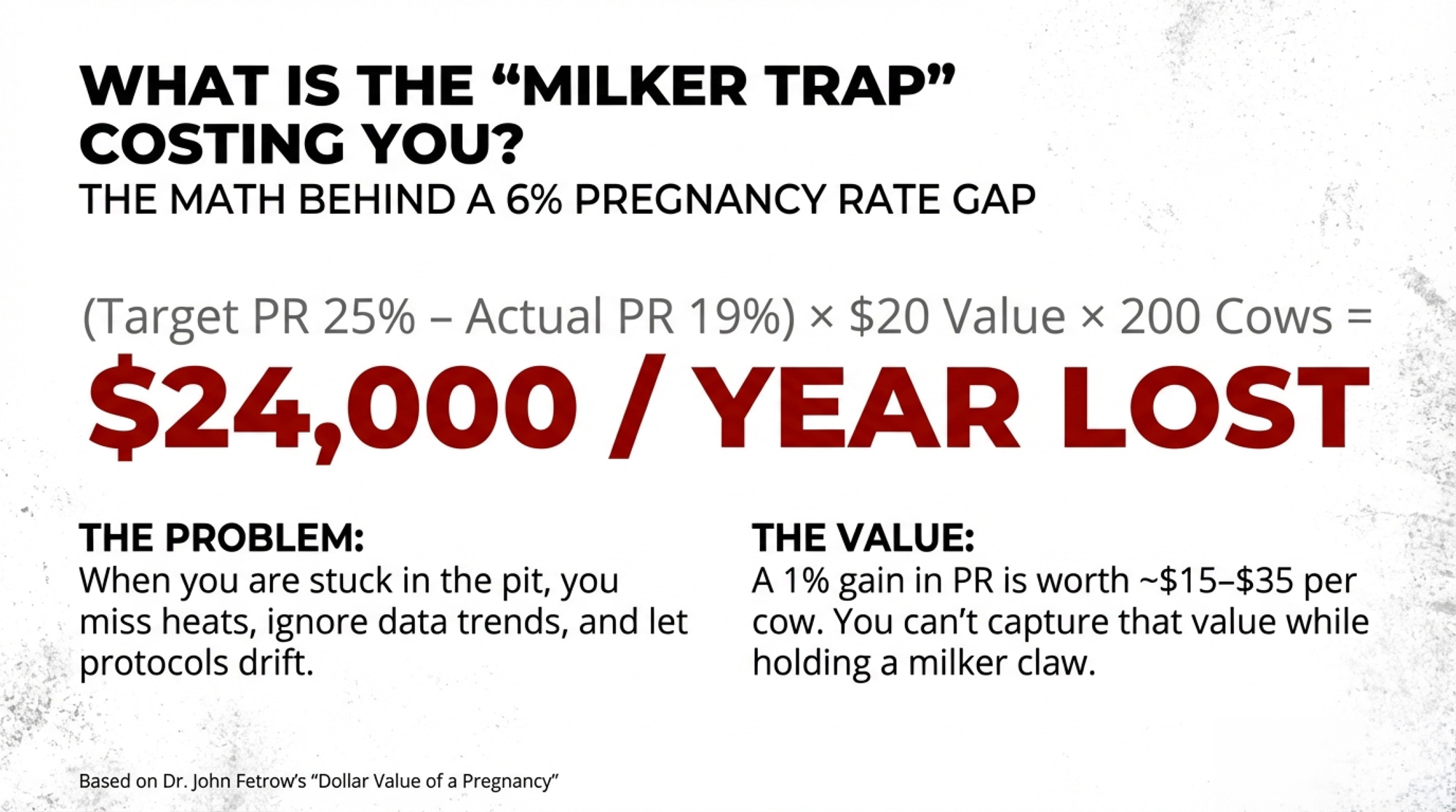

Dr. John Fetrow at the University of Minnesota laid this out in a DCRC white paper, “The Dollar Value of a Pregnancy.” A one‑point improvement in 21‑day pregnancy rate is worth about US$15 to US$35 per cow per year, depending on milk price, replacement heifer cost, and cull value. One pregnancy was worth roughly US$200 to US$600, and every extra day open cost between US$2 and US$6.

Here’s what that looks like on a 200‑cow freestall. Say your 21‑day pregnancy rate is 19%. A neighbour with similar genetics and facilities sits at 25%. Six‑point gap.

Fetrow’s formula, simplified:

Annual cost = (PR target − PR actual) × value per point × herd size

Plug in the middle of his range:

(25 − 19) × US$20 × 200 cows = US$24,000 per year

Low end at US$15 per point: US$18,000. High end at US$35: US$42,000. Same cows, same facilities, just different repro management.

| Your 21-Day Pregnancy Rate | Neighbour’s PR (Target) | Annual Cost at $20/Point | Range ($15–$35/Point) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15% | 25% | $40,000 | $30,000 – $70,000 |

| 17% | 25% | $32,000 | $24,000 – $56,000 |

| 19% | 25% | $24,000 | $18,000 – $42,000 |

| 22% | 25% | $12,000 | $9,000 – $21,000 |

The University of Wisconsin’s “Repro Money” program – developed by UW–Madison’s Department of Dairy Science with UW–Extension – tested this on real farms. Forty Wisconsin dairies completed the team‑based program. On average, they lifted 21‑day pregnancy rate by two points and saw an estimated economic gain of US$31 per cow per year. No new sheds. No shiny robots. Mostly structure: advisory teams, clearer repro protocols, regular review meetings.

On 200 cows, that Repro Money average is US$6,200 a year. On 300 cows, US$9,300. Run Fetrow’s six‑point example at US$20 and you’re back at US$24,000‑plus territory.

You don’t fix a pregnancy‑rate problem from inside the parlour. You fix it with better heat detection, cleaner data, tighter protocols, and a team that’s trained and trusted to execute. That’s owner work. Not milker work.

What Jobs Actually Did – and What Smart Dairy Owners Do

Jobs didn’t write code, machine cases, or design circuit boards. He surrounded himself with people who could, then obsessed over decisions, not tasks. On a dairy, the parallels are closer than most owners want to admit.

Product vision → herd vision. Jobs decided the Mac would be cheap, beautiful, and easy to use – not a Lisa clone and not a hobbyist box. On your farm, this is the one‑sentence answer to “What is this herd optimized for?” Cash flow? Components? Low‑labour lifestyle? If you can’t say it in a sentence, your team can’t execute it.

Team‑building → hiring and developing your people. Jobs poached Andy Hertzfeld from the Apple II team, pulled Bill Atkinson from the Lisa project, gave Burrell Smith freedom to build prototypes until something clicked. Kirk did his own version. According to the AHDB profile, he invested in Harrison – including sending him to the U.S. with Worldwide Sires for a week to visit American herds and breeders – then handed him real responsibility when he came back. That’s not “help.” That’s succession in slow motion.

System design → SOPs and data flows. Jobs killed features engineers loved if they made the Mac feel clunky. On your farm, that’s your milking routine, your fresh‑cow checks, your repro protocol, and how data moves from parlour or robot into decisions. CAFRE in Northern Ireland puts it bluntly: “It does not matter if a dairy producer has the best milking parlour feeding system and housing in the world, if employees do not perform their tasks consistently, herd health and performance will suffer.”

And the big one.

Saying “no” → culling tasks off the owner’s plate. Jobs killed the internal fan and a floppy port on the original Mac because he cared more about noise and simplicity than backward compatibility. On a dairy, saying “no” means dropping unprofitable side projects, stepping away from that one milking shift your ego says only you can run, or killing a tradition once the math proves it doesn’t work.

The owner’s “unit of work” has to shift from “hours in the parlour” to “decisions per week that move net margin.”

That single sentence is worth putting on your office wall.

Are You Designing the System – or Just Running Laps Inside It?

Great cows don’t help much if the person running the breeding list is too tired to see a cow in heat.

Grab a scrap of paper and be honest with yourself.

- Where do you spend your first hour every morning? Looking at repro lists and yesterday’s data, or already halfway through a milking shift?

- Who actually makes breeding decisions? You set a plan and trust someone to handle heat detection and AI – or you personally breed every cow and heifer because “nobody else will do it right”?

- What happens if you’re gone for three days? Do metrics hold, or do SCC and repro numbers wobble the moment you leave the yard?

- How often do you review cost of production and labour cost per cwt? Monthly at minimum, or “whenever the accountant sends something”?

If your answers land in the second column more than twice, you’ve probably found the real bottleneck on your operation. And it’s the name on the mailbox.

Do Robots and Sensors Fix the Lone‑Wolf Problem?

Jobs was obsessed with user experience – he wanted people to turn a Mac on and just know what to do. Today’s dairy tech sells a similar promise. Robots milking around the clock. Collars flagging heats and health events. Sort gates moving the right cows at the right time.

The uncomfortable truth: robots and sensors don’t fix the lone‑wolf problem if the owner still insists on personally watching every exception and making every micro‑decision.

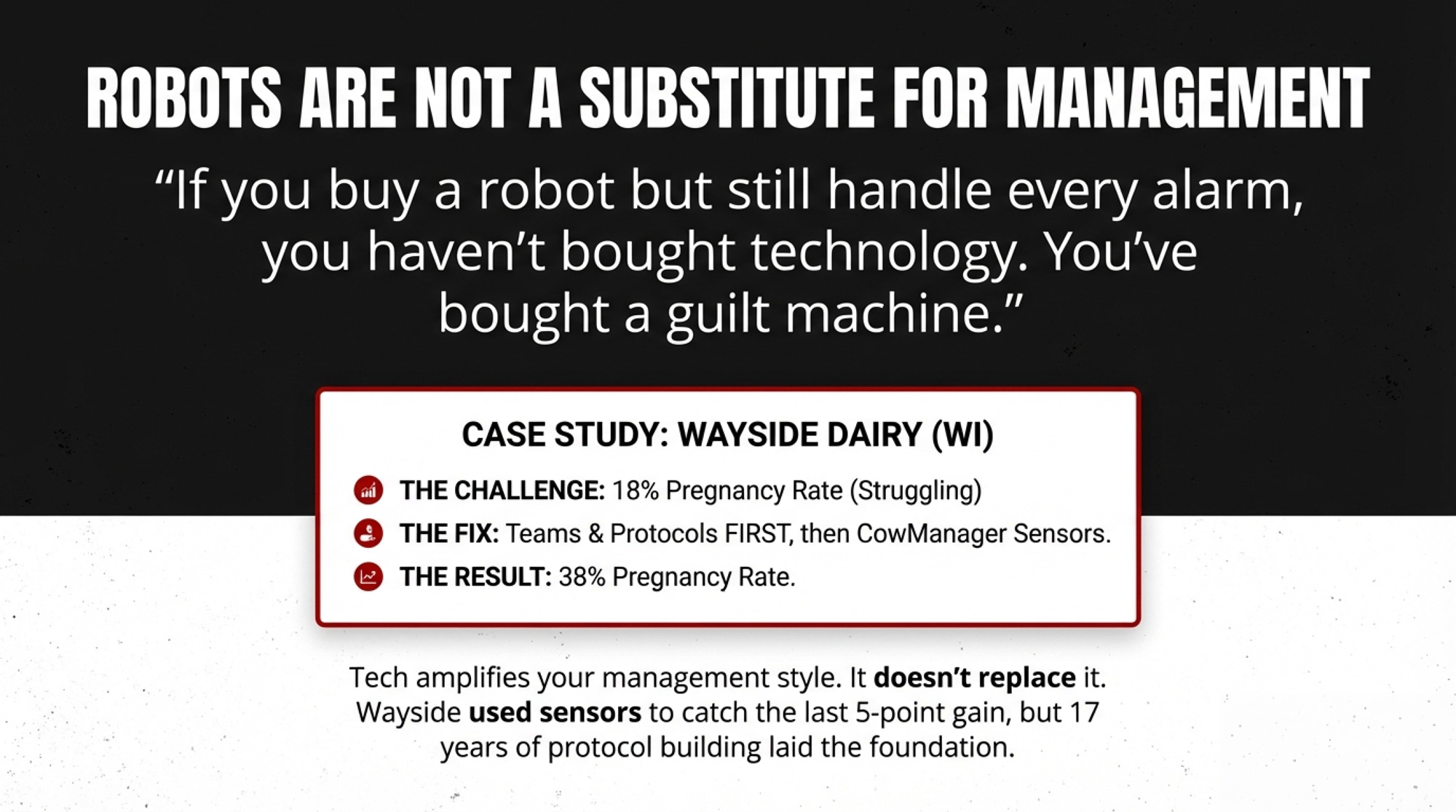

Look at Wayside Dairy LLC near Green Bay, Wisconsin. Co‑owners Jeremy Natzke, his father Dan, sister Jenna Nonemacher, and partner Jesse Dvorchek milk about 2,000 cows with 1,850 replacements, rolling herd average around 32,171 lb with 4.3% butterfat and 3.3% protein . For years their pregnancy rate hovered around 18% . Over roughly 17 years they brought in a new vet, changed nutritionists, implemented a double Lutalyse shot program, and added a 4 mL dose of GnRH 10 days before first breeding . “We kept asking consultants how we can improve,” Natzke told Bovine Veterinarian Online .

Those management changes – not a piece of stainless steel – lifted Wayside’s pregnancy rate to about 33%. Then, in mid‑2020, they installed CowManager ear sensors across the herd. In a Select Sires case study published in September 2022, Natzke said, “The return on investment with CowManager is really very quick. What it does is allow us to spend more time with the animals that need more attention”. By then, their pregnancy rate had climbed to 38% – because the Fertility alerts catch more cows on natural heats, reducing how many need the synchronization program and saving on both drug costs and labour.

Seventeen years of decisions, protocols, and team development built the foundation. The sensors made it easier to catch that last five‑point gain because the system was already there to act on the data.

| Task | The “Robot/Sensor” Job | The “Owner/Designer” Job |

| Heat Detection | 24/7 Activity/Rumination Alerts | Setting the “Threshold” for Intervention |

| Milking | Unit Attachment & Milk Mapping | Reviewing Quarter-Level SCC Trends |

| Health | Flagging “Off-Feed” or High Temp | Consulting Vet on Treatment Protocols |

| Data | Recording the 1,000 Events | Deciding which 3 Events matter today |

| Succession / Lifestyle | Providing a functional asset | Ensuring the farm is a life the next generation wants, not just a job they have. |

If you bought a robot and still insist on being the robot, you didn’t buy technology. You bought a guilt machine.

The right tech lets you work more like Jobs: set the rules, watch a dashboard, make a handful of big calls, step in only when the system throws a true red flag. The wrong mindset turns every robot alarm into another reason you can’t ever leave the yard.

Options and Trade‑Offs for Letting Go of the Milker Claw

There’s no single path out of the lone‑wolf trap. Herd size, labour market, and bank account all shape what’s realistic. But the data points to patterns that work – and each one carries real friction you should know about upfront.

| Milestone | Action Item | Target Metric |

| Day 1 | Write the “One-Page SOP” for the AM shift. | Zero ambiguity in prep/post-dip. |

| Day 15 | Side-by-side training with “Shift Lead.” | 100% protocol compliance. |

| Day 30 | Owner Vacates Shift. | Track SCC & Bulk Tank Weight. |

| Day 90 | Reallocate 15 hours/week to Repro Data. | +1.5 points in 21-day PR. |

Path 1: The 30‑Day Milking Test (Any Herd Size – Start This Month)

Steve Jobs’ first move wasn’t to code faster – it was to get out of the weeds. On your farm, that starts with one milking shift per day you’re willing to be absent from within 30 days. Write how you want that shift to run on one page: cow flow, prep routine, unit attachment, post‑dip, wash‑up. If you can’t fit it on a page, you don’t have a standard. You have a wish.

Train one person to run that shift to that page. Pay them for the responsibility. Then for 30 days, track three numbers: milk shipped per cow, bulk tank SCC, and how many cows hit your mastitis treatment list. If numbers hold, that shift becomes “owner‑optional” permanently.

If they slip, that’s not proof delegation fails. It’s proof you’ve got training or clarity gaps to fix. Don’t run back into the parlour and tell yourself “nobody cares like I do.” Fix the gap.

That first owner‑free milking is the proof your system works, not just your back.

Path 2: Strategic Reallocation on 150–500‑Cow Herds

This is where Kirk lives. When he stepped out of one milking, he freed up 3–4 hours a day. According to the AHDB profile, he put those hours into consistent feed push‑ups to lift dry matter intake, a daily chalking routine for heat detection at the same time every day, and investing in Harrison’s skills.

Those changes helped move his pregnancy rate from 20% to 25%. Run Fetrow’s math on 300 cows at US$20 per point:

(25 − 20) × US$20 × 300 cows = US$30,000 per year

At the low end (US$15): US$22,500. High end (US$35): US$52,500. That’s the kind of margin movement that separates “covering the bank” from “actually getting ahead.”

The risk is real: for the first 60 days, it’ll feel like standards are slipping. You’ll see things you don’t like. Treat that as feedback on your system, not proof that stepping back was a mistake.

Path 3: The Team Build on 500+ Cow Herds

Above 500 cows, the question isn’t whether to delegate. It’s whether you’re doing it with structure.

Written SOPs, weekly team meetings, and outside advisors earn their keep here. The UW Repro Money program showed that when farms created farmer‑led repro teams – owner, vet, nutritionist, key staff – and actually met, average pregnancy rate improved by two points at about US$31 per cow per year. On a 700‑cow herd, that’s US$21,700 annually from repro alone.

Forty farms completed the program . They didn’t keep meeting out of politeness. They kept meeting because the numbers moved.

The risk? Meetings for the sake of meetings. Simple fix: every meeting ends with three things written down. One protocol tweak. One training commitment. One number to check before the next meeting. Without those, you had coffee, not a team.

Path 4: The Financial Reckoning When U.S. Margins Are Tight

If your all‑milk price hovers close to your cost of production, you can’t afford to spend 70 hours a week doing work you could hire a livestock worker to do. USDA’s Farm Labor report for January 2025 pegged the national average at US$18.15/hour for livestock workers. In the Great Lakes region – Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan – the 2024 annual average ran US$17.68/hour. That’s roughly US$37,750 in base wages for a full‑time position, or about US$47,000–$49,000 once you load in payroll taxes, workers’ comp, and basic benefits.

Meanwhile, US$50‑to‑US$100/hour decisions – breeding strategy, capital allocation, lender negotiations, ration‑level changes – keep getting pushed “to when it’s quieter.”

Cornell’s DFBS numbers are blunt. Bottom‑quartile farms spent about US$22.32/cwt in operating costs. Top‑quartile farms: US$15.79/cwt. Gap of US$6.53/cwt. On a 200‑cow herd shipping 75 lb/day, that’s roughly 5,475 cwt a year × US$6.53 = about US$35,750 per year.

Not all of that gap is labour. But your lender already knows which side you’re on – they see your cost per cwt long before you do.

As labour tightens and margins compress through 2026–2027, farms that already treat owner time as a strategic resource will flex – cut hours, keep performance, absorb shocks. Farms that keep using the owner as the cheapest milker in the barn will break first.

| Path | Upfront Cost | Payback Timeline | Expected Annual Gain | Biggest Friction Point |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-Day Milking Test | $0–$2,000 (training time) | 30–60 days | 3–4 hrs/day freed | Feels like losing control first 2 weeks |

| Strategic Reallocation (150–500 cows) | $37,750–$49,000 (one FTE) | 6–12 months | $22,500–$52,500 (5-pt PR gain) | Standards slip for 60 days during transition |

| Team Build (500+ cows) | $5,000–$15,000 (SOPs + advisor time) | 4–6 months | $21,700+ (2-pt PR gain, 700 cows) | Meetings feel like busywork without strict 3-item close |

| Financial Reckoning | $0 (audit existing time use) | Immediate insight | $35,750 (closing Cornell cost gap) | Admitting you’re the bottleneck, not the hero |

Tech Investment: What the Numbers Actually Look Like

If you’re weighing sensors against robots, the cost gap is worth spelling out. Ear‑tag monitoring systems like CowManager run about US$0.07 per head per day according to CowManager reps – roughly US$25.55 per cow per year. Activity monitoring platforms more broadly (collars and ear tags combined) range from US$80–$150 per cow in hardware, plus base station equipment (US$2,500–$5,000) and software licensing (US$1,800–$3,600 annually), putting a 200‑cow operation at roughly US$20,000–$38,600 all‑in for the first year.

A full robot string? US$400,000‑plus per unit once you count construction.

That doesn’t mean robots are wrong. It means the investment decision needs to match your actual bottleneck. If your bottleneck is information – catching heats, flagging health events, getting data into decisions faster – sensors at US$25/cow/year are a different conversation than robots at six figures.

| Technology | Cost per Cow (Year 1) | 200-Cow Herd All-In | Bottleneck It Solves |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ear-Tag Sensors (e.g., CowManager) | $25.55/year | $5,110/year (ongoing) | Information: catching heats, health alerts, getting data into decisions faster |

| Activity Monitoring Platform (collars/tags + infrastructure) | $100–$190 | $20,000–$38,600 | Information + protocol consistency: 24/7 monitoring, automated alerts, team accountability |

| Single Robot Unit (incl. construction) | $2,000+ | $400,000+ | Labour replacement: physical milking task automation, BUT only if system/team already works |

| Full Robot String (3–4 units, 600+ cows) | $2,000–$2,500+ | $1.2M–$1.5M+ | Scale labour constraint: enabling herd growth when local labour market fails |

Key Takeaways

- If you can’t miss one milking a day without stressing out, your 30‑day goal is simple: pick a shift, write a one‑page SOP, train one person, track SCC and milk per cow for a month. Numbers hold? That shift is owner‑optional from now on.

- If your 21‑day pregnancy rate sits below 22%, run Fetrow’s formula with your own herd size this week. If the number makes your stomach drop, book a repro team meeting with your vet and nutritionist and commit to one protocol change within 60 days.

- If your name shows up more than three times on the “who handles exceptions” list for robots or sensors, you’ve found your bottleneck. Write down what the tech is responsible for and what humans handle. Pick one area to hand off within 90 days.

- If you haven’t reviewed cost per cwt and labour cost per cwt with your lender in six months, that’s your next call. Within a year, you want your time usage mapped well enough to say, with a straight face, “Here’s what I earn per hour of owner work.”

- If your job description still reads ‘chief milker,’ remember Jobs didn’t prove his worth by living in the lab. He proved it by building a lab that worked when he walked out the door.

The Bottom Line

Ten years from now, the herds still standing will be owned by people who stopped pretending they were the machine and started acting like the designer – more Steve Jobs than “hired milker in chief.”

So this year – when you look at your own time sheet, even if it’s just the back of an envelope – which job are you training for?

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Ditch the Daily Walks: How Precision Monitoring Cuts Labor by 40% While Boosting Transition Success – Stop burning expensive hours on healthy cows and pivot your focus to the 15% that actually need attention. This operational deep-dive delivers a proven blueprint for slashing transition labor by 40% while capturing elite milk peaks.

- Decide or Decline: 2025 and the Future of Mid-Size Dairies – Exposes the hidden equity drain facing herds without a clear five-year strategy. It arms you with the financial stress-tests and regional benchmarks necessary to decide whether to scale up, optimize, or pivot before the 2026-2027 market reset.

- Ditching Robot Pellets: How Smart Farms Save $36,000 and Improve Milk Components – Challenges the expensive “standard” of robotic feeding and reveals how elite producers are pocketing an extra $36,000 annually. This disruptor’s guide breaks down the forage-first systems that boost butterfat while simplifying your daily management load.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.