If your spouse runs the books, calves, and fresh cows but isn’t on the papers, divorce or death could cost you a field.

Executive Summary: Many dairy farms in 2024–2026 are asset‑rich but exposed: one spouse holds the land, quota, and loans, while the other runs books, calves, fresh cows, and staff with no legal stake. Under Ontario’s Net Family Property rules and U.S. marital‑property laws, that setup can turn unpaid spousal work into forced land sales or crushing equalization payments when divorce or death hits. Drawing on Canadian consolidation data, global research on women in agriculture, and Root Capital’s finding that women‑led enterprises have a 4.12‑point lower default rate, this piece shows why treating spousal roles as “helping out” is now a business risk, not just a family issue. It walks through three practical tools—spousal partnerships, shared incorporation, and employment agreements—and shows how real farms like West River Farm in B.C., Korn Dairy in Idaho, and the Kaaria family in Kenya have formalized women’s roles while improving resilience. Producers get a clear winter playbook to map who owns what, put a value on invisible work, stress‑test their structure with advisors, and bring the next generation into frank succession talks. The goal isn’t more paperwork; it’s making sure the person who keeps your herd and cash flow on track also shows up on the documents that decide who keeps the farm.

If your spouse is doing the books, calves, fresh cows, and people management but isn’t on the papers, your dairy is one bad life event away from a legal and financial mess. In a high‑asset, high‑rate environment, family farms sitting on millions in land, quota, and steel but short on cash can be pushed into land sales or ugly buy‑outs when divorce or death hits. The fix isn’t magic. It’s structure: partnerships, shares, or wages that match who actually keeps the place running.

The Hard Question Nobody Wants to Ask

If you’re milking cows in 2024–2026, you’re thinking about milk price, feed costs, labour, interest rates, robots, genetics, maybe even beef‑on‑dairy. But here’s the hard truth: a lot of family dairies are running into the riskiest part of your business: who actually owns it on paper when divorce, death, or succession comes up.

On an Ontario dairy not that long ago, a couple split after more than twenty years of milking Holsteins together. His name was on the land, the quota, and the chopper. Hers was on the calf cards, the feed sheets, and the QuickBooks file. Like many Ontario dairies, they had significant value in land, quota, and steel on paper—and a lot less cash in the bank to fund any payout. When the lawyers applied Ontario’s Net Family Property rules—the system that compares how much each spouse’s net worth grew during the marriage and then equalizes the difference—he ended up owing a substantial equalization payment, took on new debt, and sold a field he’d always pictured his kids cropping someday. She left with some money in hand, but no direct ownership stake in the business she’d poured half her life into.

You probably know a version of that story in your own county. When you strip away the legal jargon, three realities keep coming up:

- Your dairy probably leans hard on women’s unpaid and often invisible work.

- The law doesn’t automatically treat that work as ownership, even if everyone on the yard knows the farm wouldn’t run without it.

- When women are formal business partners or co‑leaders, there’s solid evidence that businesses are more stable and handle shocks better.

If cows, cash flow, genetics progress, and succession all depend on those roles, why leave them off the paperwork?

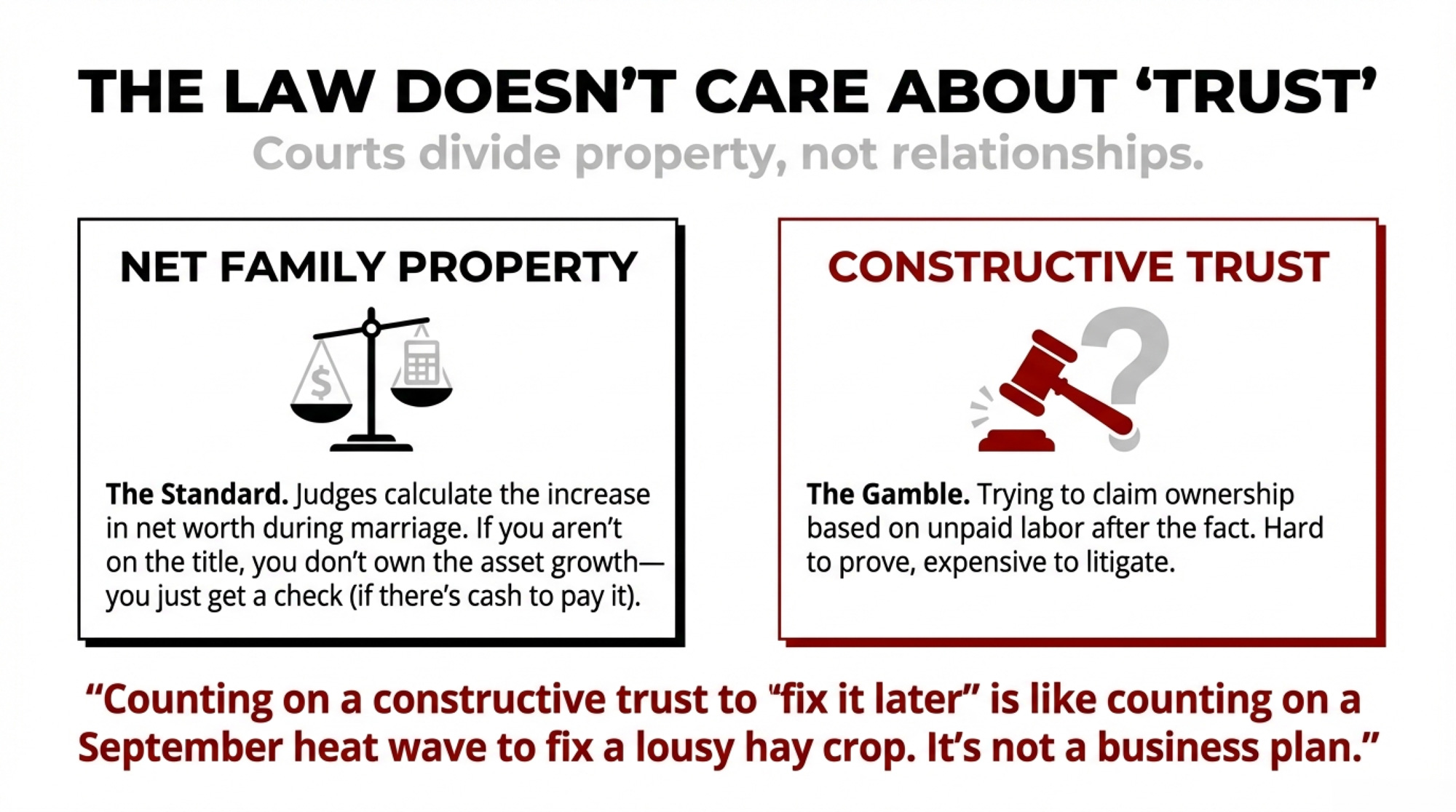

What the Law Actually Sees on Your Farm

Let’s start with the part you hope you’ll never test: what the law actually sees when a marriage ends.

In Ontario, when a legally married couple separates, the Family Law Act doesn’t say “split the farm down the middle.” It uses “equalization of Net Family Property.” Each spouse calculates their net worth on the date of separation, subtracts their net worth on the date of marriage (with special rules for the matrimonial home), and the spouse whose Net Family Property grew more pays the other spouse half the difference. One 2024 family‑law explainer puts it bluntly: it’s not the assets that are shared, it’s the increase in net worth during the marriage.

On many family dairies, that can look like this in practice:

- Land, barns, milk quota, and major equipment registered to one spouse, or to a company that the spouse controls.

- The other spouse is doing the books, feeding calves, tracking treatments, watching fresh cows, and handling a lot of informal HR.

- When the marriage ends, the spouse on title owes an equalization payment. The other spouse doesn’t automatically get co‑ownership of land or quota unless there’s a contract or a successful extra claim like unjust enrichment or constructive trust.

Farm‑law commentators in Ontario say judges often treat the equalization payment as the main way to compensate a disadvantaged spouse and are cautious about adding a constructive trust on top, because it can look like double‑compensation. The constructive trust tool is there, but it’s not guaranteed, and it usually takes a long legal fight to get it.

Counting on a constructive trust to “fix it later” is like counting on a September heat wave to fix a lousy hay crop. It might bail you out once in a while. It’s not a business plan.

In the U.S., the labels change—community property in places like California and Washington, equitable distribution in states like Wisconsin and New York—but the basic frame is similar. Property division depends heavily on whose name is on the title, how state law draws the line between “marital” and “separate” property, and what’s in any pre‑ or post‑nuptial agreements. “She’s always helped me on the farm” doesn’t carry much weight unless there’s paper behind it.

Two extra wrinkles that often get missed:

- Common‑law or long‑term unmarried partners can face very different rules than legally married spouses, depending on the province or state. Get local legal advice if your relationship isn’t formally registered.

- In some places, the house is treated differently from the rest of the farm, even if it sits right in the middle of your lanes and bunks.

The main pattern is this: if a spouse’s role isn’t formalized before there’s a crisis, the outcome is driven by statutes and judges—not by your idea of what’s fair or by who’s actually kept the wheels turning.

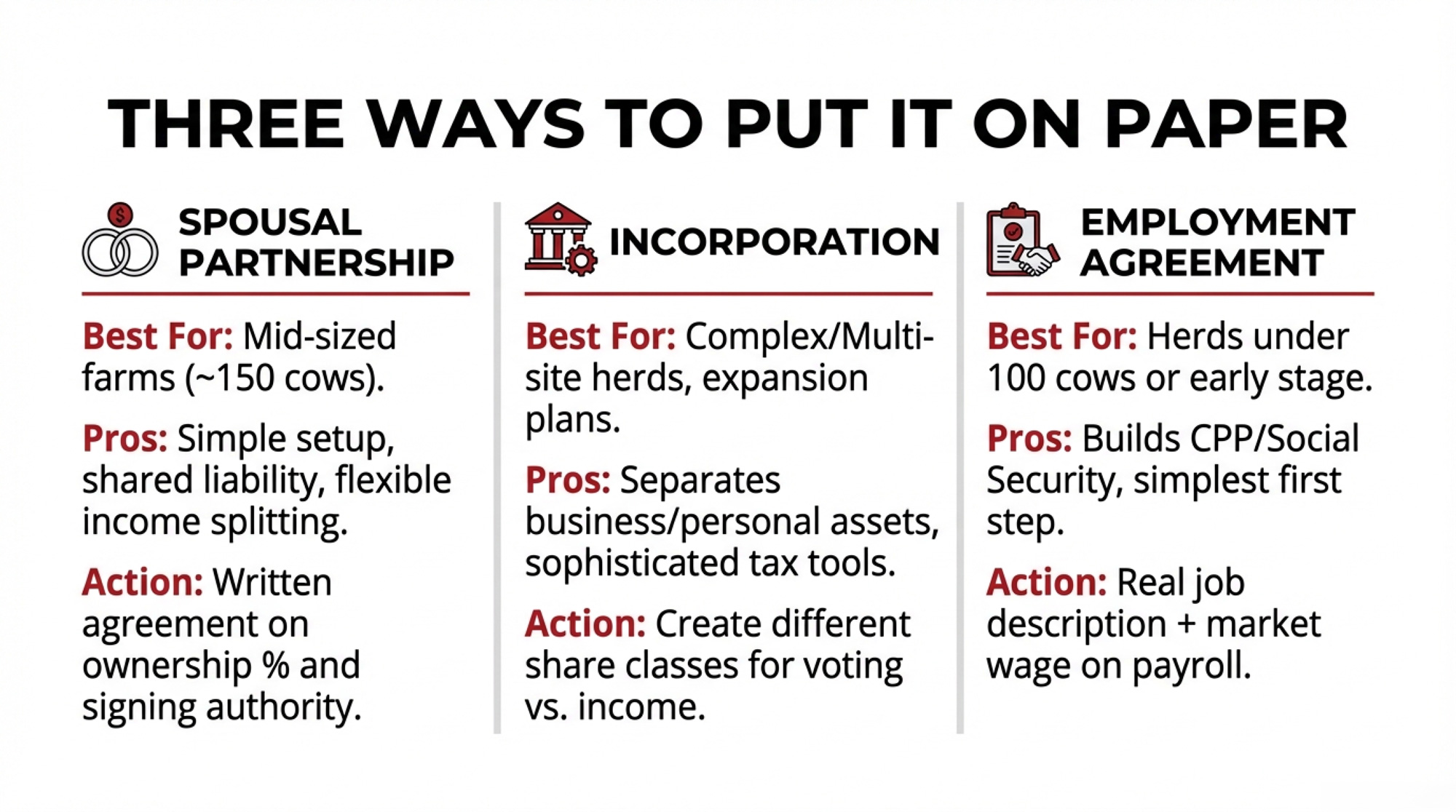

Quick Comparison on Your Phone: Partnership, Shares, or Wage?

Here’s a simple, high‑level comparison you can glance at while the parlour turns or the robot finishes a group. This isn’t legal advice; it’s how these tools usually behave on real farms once the dust settles.

| Feature | Spousal Partnership | Incorporation (Shareholder) | Employment Agreement |

| Setup cost | Generally low to moderate (professional time, legal/accounting fees) | Generally higher (legal setup, possible asset roll‑in, ongoing corporate costs) | Minimal (HR/payroll setup, advisor time) |

| Legal protection | Shared liability; both partners on the hook | Higher separation between business and personal assets when structured properly | Primarily wage‑based; no ownership by default |

| Complexity | Relatively simple once agreement is in place | Higher (annual filings, corporate records, shareholder agreements) | Low (but still needs a clear job description and pay structure) |

| Best for | Mid‑sized family farms wanting shared decision‑making | Larger or more complex operations with multiple stakeholders or growth plans | Early‑stage operations or herds under ~100 cows are starting to formalize roles |

The “right” column for you depends on herd size, debt level, family goals, and how you’re handling genetics, management, and expansion decisions over the next 5–10 years. If you’re under roughly 150–200 cows with a simple ownership picture, a spousal partnership is often the first rung. Once you’re multi‑site or have several stakeholders, incorporation is usually required. That’s a pattern, not a hard rule.

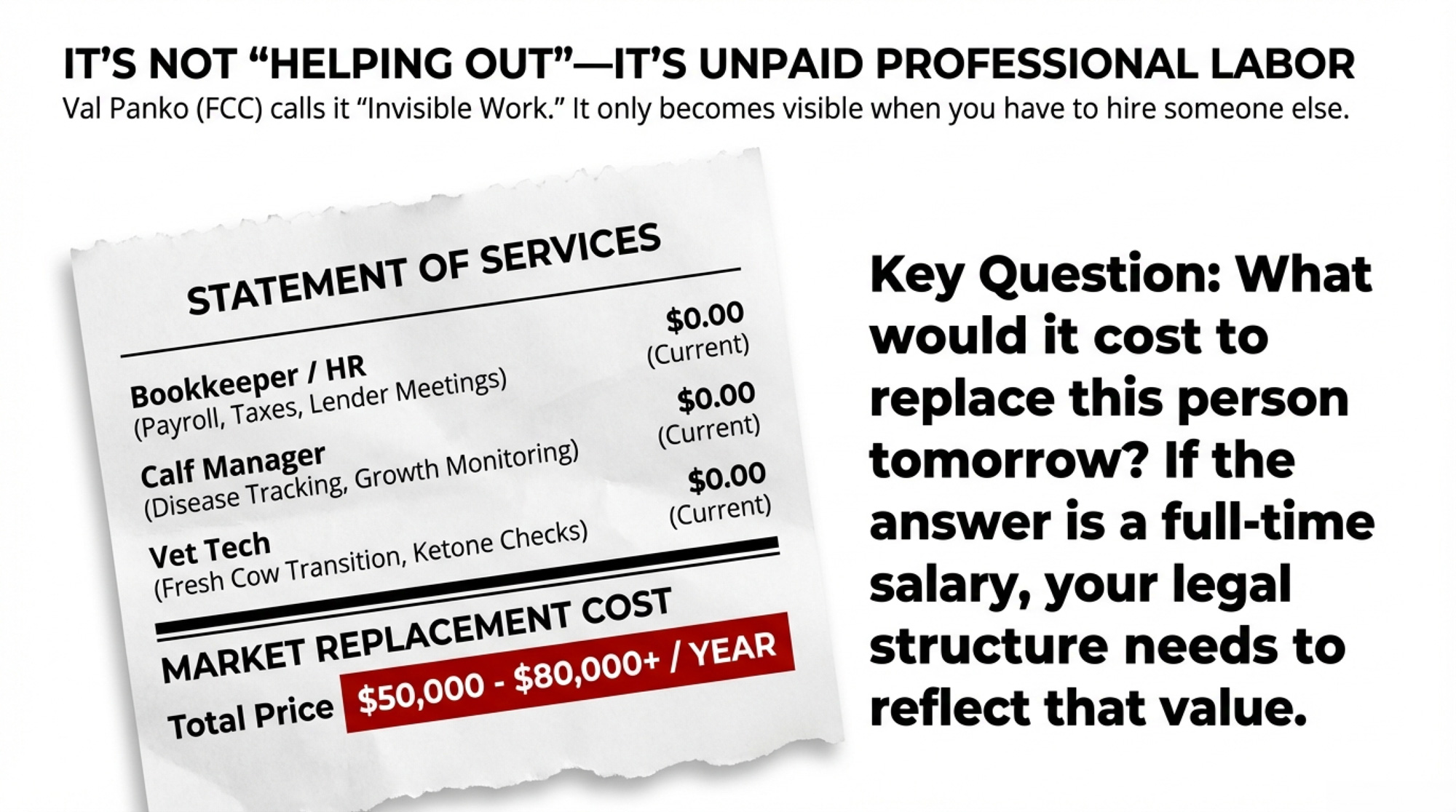

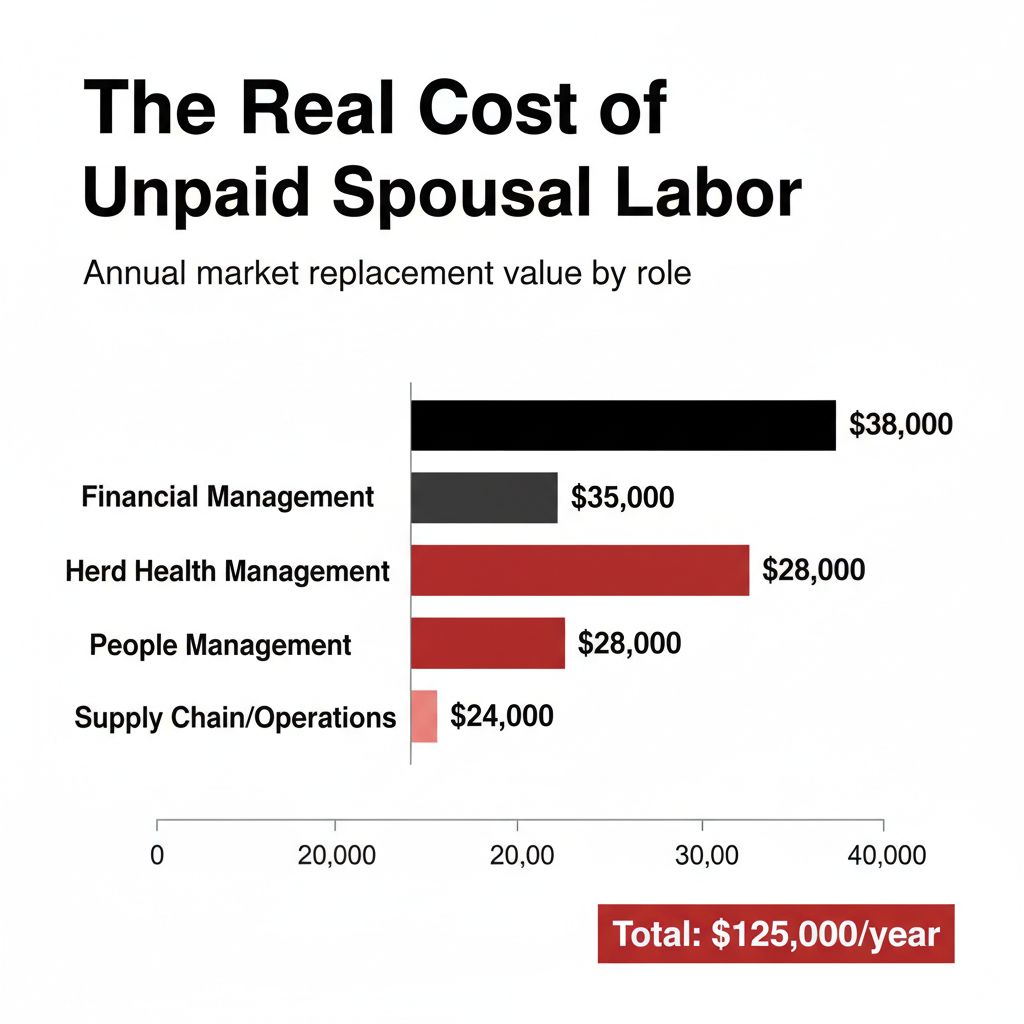

When “Invisible Work” Finally Gets a Price Tag

All of this sounds pretty legal until you sit down at the kitchen table and write out who’s doing what. That’s where it stops being theoretical.

Val Panko, a business advisor with Farm Credit Canada who works with farm families across the Prairies, has been talking a lot about what she calls “invisible work”—jobs on farms, often done by women, that “don’t show up on a T4” but are absolutely critical to the business. In a 2025 Western Producer feature, she notes that this work is usually only properly discussed when families start formal succession planning and an advisor forces everyone to list roles.

According to Panko, the list almost always starts with something like, “Dad milks and makes the decisions.” Then they keep talking, and it turns out Mom is:

- Keeping the books, handling payroll, and meeting with the accountant and lender.

- Scheduling the vet, logging treatments, and keeping herd‑health records straight.

- Running calf and heifer programs—hutches, group pens, or dry lot systems—and tracking growth and disease.

- Coordinating relief milkers and seasonal help, including all the messy people issues.

- Watching fresh cows through the transition period to make sure protocols like ketone checks actually happen, and early problems get caught.

None of that shows up on a pay stub if she’s not officially paid. But once families start asking “What would it cost to replace this?” and look at what local postings pay for a bookkeeper, calf manager, or office manager, many realize they’ve been leaning on the equivalent of at least one significant part‑time—and often a full‑time—position in unpaid labour. On a 90‑cow Ontario dairy grossing a few hundred thousand dollars a year, that’s a serious chunk of risk in one person who might have no legal stake.

Panko also points out that some families don’t really see it until they start outsourcing pieces of that work—paying a catering company to get hot meals to the field during harvest, for example—because nobody at home has the bandwidth to cook anymore. That’s when the “free” labour suddenly gets a line item.

Putting a precise dollar figure on invisible work is almost impossible because it’s woven into daily life. But the moment you look at realistic replacement costs, its economic weight becomes obvious. That first honest task map almost always reveals that the “non‑owner” spouse is quietly covering the equivalent of multiple paid positions.

This isn’t just a Canadian story. Purdue Extension’s succession‑planning team in Indiana has been working with farm families for well over a decade. In their “Secure Your Future” materials, they stress the importance of clearly defined roles and expectations, because fuzzy responsibilities and unspoken assumptions—often around spousal labour—are a common source of tension in succession talks. The details change from county to county, but the pattern doesn’t.

Everyone on the farm usually knows who’s keeping things together. It just doesn’t always show up in the legal or financial structure—until an advisor drags it into the open, or a divorce lawyer does.

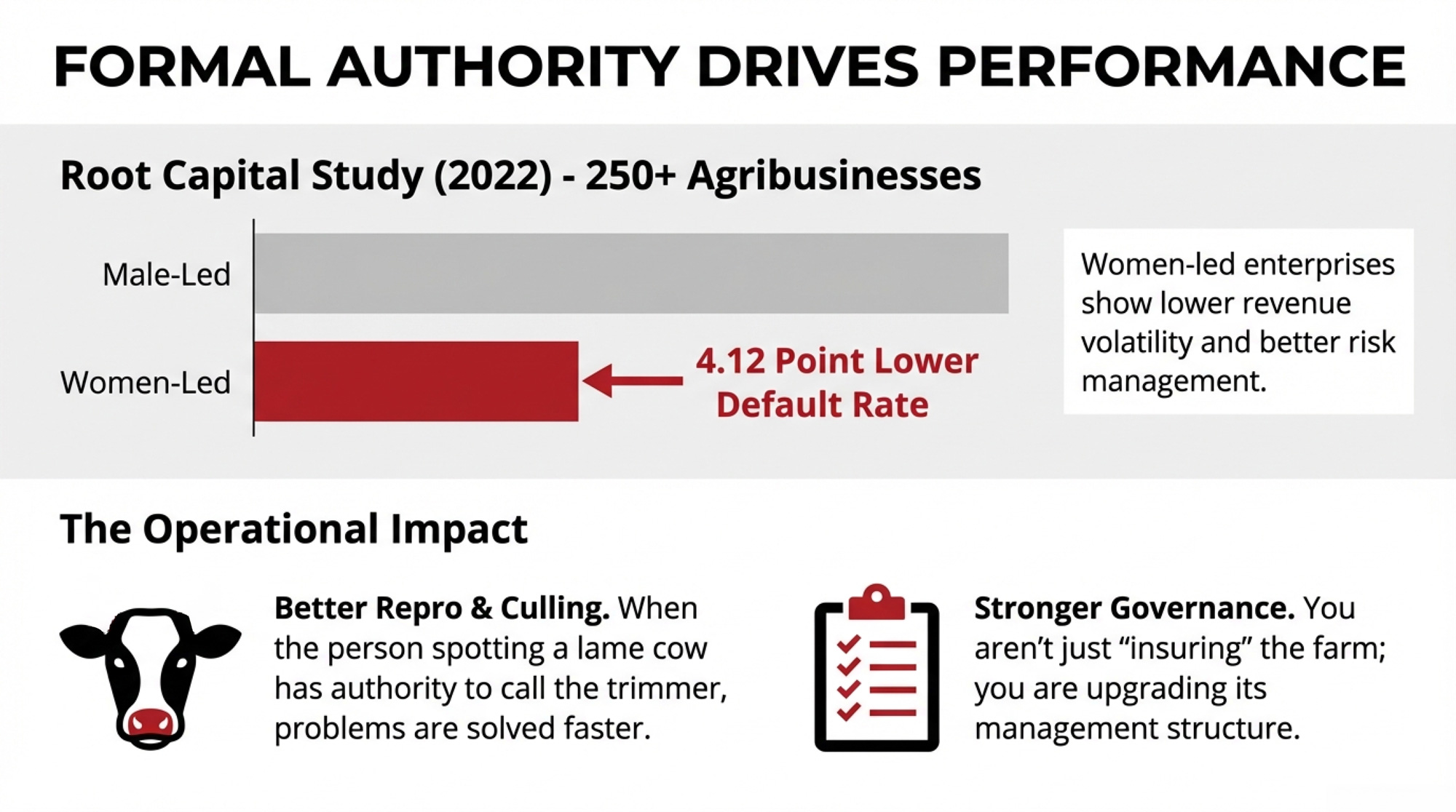

What the Data Says When Women Actually Have a Say

So far, we’ve talked about risk and recognition. The next question is obvious: does formalizing these roles actually move the needle on performance?

When Women Have the Same Tools

There’s a decent stack of agricultural economics research on gender and productivity. Most of it isn’t dairy‑specific, but the patterns are worth paying attention to.

World Bank–linked work and systematic reviews of agricultural value‑chain projects in countries like Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, and Uganda show a consistent pattern: when women’s plots yield less than men’s, the gap almost always traces back to different access to land, fertilizer, hired labour, and extension—not to ability. When you control for those differences, most of the yield gap disappears.

A mixed‑methods systematic review on women’s economic empowerment in agriculture, published in the early 2020s, found that when women have equal access to productive resources, they achieve similar yields to men. Several African case studies are summarized in a gender‑focused ag‑finance research report that shows that when women have comparable access to land and inputs, their plots can be as technically efficient as men’s. The point is the same: the gap is usually about access, not ability.

World Bank–supported analysis using the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) in places like Bangladesh has shown that higher empowerment scores—more say over production, income, and time use—are associated with higher farm productivity and better resilience to shocks. What that means for you: when both partners can actually make calls, problems get caught earlier, and responses are faster.

When Women Are in the Finance Seat

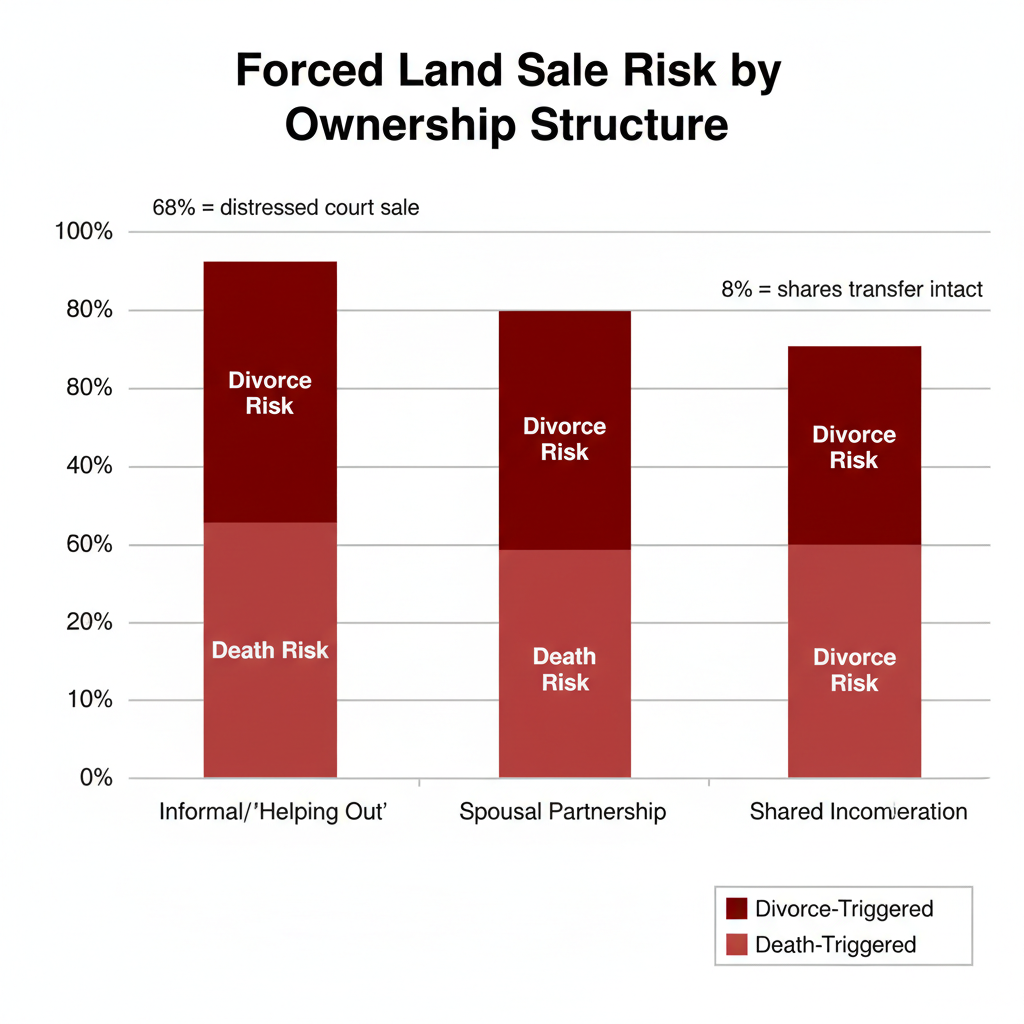

On the finance side, Root Capital—a lender working with agricultural businesses in Latin America, Africa, and Indonesia—put some solid numbers to this question. In its 2022 report, “Inclusion Pays: The Returns on Investing in Women in Agriculture,” Root Capital analyzed more than 250 agribusinesses over roughly a decade, comparing those led by women with those led by men.

| Ownership Structure | Default Rate | Legal Protection | Asset Risk on Divorce/Death |

| Formally Documented Women-Led Enterprises | 3.88% | Full contractual + marital property rights | Low – shared assets protected |

| Invisible/Informal Partnership (“Helping Out”) | 8.00% | None – no legal standing | Critical – forced land sale likely |

| Spousal Partnership Agreement (Documented) | 4.12% | Moderate – depends on jurisdiction | Moderate – some protection |

| Shared Incorporation | 3.95% | Strong – corporate veil + shareholder rights | Low – business continuity preserved |

They found that women‑led enterprises in their portfolio had lower year‑to‑year revenue volatility and lower loan default rates than those not led by women. One detail that jumps off the page: women‑led clients showed an average default rate 4.12 percentage points lower than non‑women‑led clients, and the authors are careful to note that this particular figure is just shy of statistical significance. Even so, the overall pattern is clear: enterprises with more women in leadership and on staff tend to have lower default rates, and lenders may see less risk associated with those enterprises.

This isn’t a magic guarantee for your loan, and it’s not dairy‑specific. But it’s a strong signal that when women are formally part of leadership—not just “helping out”—the financial ride often gets steadier.

Where Barn Decisions Hit Repro, Culling, and Genetics

Now zoom right down into the barn, where the decisions that actually drive repro, culling, and your genetics plan get made.

A 2022 Canadian study in Frontiers in Veterinary Science surveyed dairy producers on disease‑prevention priorities and highlighted lameness, body condition, and stress management as key welfare and performance concerns. A 2024 paper in Frontiers in Animal Science on “positive welfare” reports that more producers are thinking beyond just minimizing negatives like pain and disease and are starting to factor in comfort, natural behaviour, and enrichment into their picture of good welfare.

Those papers line up with what you see in your own repro and cull data:

- Cows that calve under‑conditioned—body condition scores down in the low 2s—are much more likely to underperform early in lactation than cows calving around 3.0–3.5. That means more days open, more services per conception, and a higher chance they leave the herd for reproductive failure.

- Lame cows are less likely to conceive, take longer to get pregnant, and are more likely to be culled; multiple studies show substantially higher odds of being open at key checkpoints if a cow is lame compared with sound.

On many herds, it’s often the spouse who notices that a fresh cow is hanging back from the bunk, that a dry pen in a dry lot system isn’t bedding as dry as it should be, or that a particular heifer’s gait has changed. When that person not only has the responsibility but the authority to change bedding schedules, push for a ration tweak, or call the hoof trimmer, those early observations turn into better repro, fewer involuntary culls, stronger component and butterfat performance—and, over time, a more durable genetics strategy, because you’re not burning your best heifers on preventable problems.

If they see all that and they’re still legally treated as “helping out” with no ownership or defined role, the farm is effectively free‑riding on one of its most important managers—on both the management and the genetics side.

How Producers Are Actually Putting This on Paper

If we accept two things—that there’s real risk in leaving spousal roles informal and real upside in recognizing them—then the next question is: how do you put this on paper in a way that works on a live dairy?

Looking at what producers are doing from Atlantic Canada to Idaho to California, most lean on some mix of three tools in their family farm legal structure:

- Spousal partnerships

- Corporations with shared ownership

- Employment agreements

You don’t need to use all three. The right mix depends on herd size, how complex your business already is, how you’re investing in genetics and management, and how much compliance you’re prepared to manage.

Spousal Partnership: Simple, But Powerful

A spousal partnership is often the first, easiest step away from “it’s all in one name.”

On paper, that usually means:

- A written partnership agreement that spells out ownership percentages, capital contributions, and who’s accountable for which parts of the operation.

- An income split between partners that reflects both labour and capital, built with help from a farm‑savvy accountant.

- Clear signing authority for each partner, often with dollar thresholds for bigger decisions.

Accountants who focus on dairy farms in Ontario and the Prairies say that moving from a sole proprietorship into a spousal partnership often gives a more honest picture of how the farm actually runs—and can open up some tax planning options—if it’s structured properly. In practice, for small to mid‑sized herds, shifting into a spousal partnership is usually a winter‑project level change: a few meetings, some paperwork, and professional fees that are real but manageable relative to the value tied up in land and quota.

The real hurdle is almost never the dollars. It’s sitting at the kitchen table, saying out loud what everybody already knows, and being willing to sign it.

Incorporation With Both Spouses on the Cap Table

For larger or more complex herds—multi‑site operations in Quebec, 300‑cow robot barns in Ontario, 1,000‑cow parlour herds in the western U.S.—incorporation is often already the norm.

In that world:

- The farm runs through a company, and both spouses can own shares. Advisors often create different share classes so you can separate voting control from income rights.

- A shareholders’ agreement lays out what happens if someone wants out, dies, becomes disabled, divorces, or retires. It can define valuation formulas and buy‑out terms so you’re not inventing them in a panic.

- You use some blend of salaries and dividends to manage tax and build retirement savings, with guidance from a farm‑literate CPA.

Under Canada’s quota system, tax specialists closely monitor how land and quota are transferred into a corporation so families can use rollover provisions and capital gains exemptions where applicable. In the U.S., similar care goes into structuring S‑corps, LLCs, and partnerships with buy‑sell clauses, especially when there are off‑farm heirs or multiple siblings.

There is a trade‑off: incorporation can give you more separation between business and personal assets and more tax and transition tools over the long term, but it adds accounting and legal complexity compared with a simple partnership. This is where you want advice from someone who truly understands both dairy economics and family farm law.

Producers who’ve gone through more involved restructurings will tell you it felt like a winter’s worth of paperwork—but still cheaper and calmer than letting a judge sort out their life’s work.

Employment Agreement: A Practical First Step

Sometimes, especially on herds under 100 cows, the most realistic place to start isn’t ownership at all. It’s a wage.

That might look like:

- Writing a job description for what your spouse already does—office manager, calf/youngstock lead, HR/payroll.

- Setting a wage based on real local numbers—what job boards and wage surveys show for those roles in your area.

- Putting your spouse on payroll so they build CPP/QPP or Social Security contributions and retirement‑savings room.

On some Ontario and Wisconsin farms, the spouse holds both shares and a salaried role—say, as office manager or youngstock manager. That’s often a comfortable middle ground: they’re recognized both as an owner and as someone with a defined, paid job.

There is a cash‑flow trade‑off. Paying a wage increases your short‑term outlay, but it also builds your spouse’s personal financial stability and retirement base. If margins are tight, it may make sense to start with a modest wage and revisit it as herd size, butterfat premiums, or component pricing improve. Think of it like a piece of necessary maintenance: not exciting, but a lot cheaper than the breakdown it’s preventing.

As a rule of thumb, if your spouse is consistently covering the equivalent of half to a full‑time role and your herd is beyond “small hobby” territory—say, 80 cows or more—that’s a good signal to at least explore a formal employment agreement, a partnership, or both with your advisors. It’s not a legal threshold, just a gut check producers and advisors often use.

What Actually Changes When You Formalize Roles?

The question that comes up at almost every kitchen table is, “If we do this—change the structure, add a partnership—what really changes tomorrow?”

From the cows’ point of view, nothing. They still want feed on time, have clean stalls, and calm handling. On the business side, a few important guardrails finally appear.

Banking, Contracts, and Big Decisions

Once your lender, processor, and major suppliers are doing business with a partnership or corporation, the entity—not just one individual—is the client. That makes it easier to spell out who can sign what.

In practice, that often means:

- Either spouse can sign cheques up to a set amount; cheques over that amount require both signatures.

- New debt or long‑term leases over an agreed threshold require joint sign‑off.

- Major moves—buying or selling land, building a new barn, taking on large equipment financing—are defined in your agreement as decisions you make together.

That doesn’t change who orders mineral or who calls the hoof trimmer. But it makes it a lot harder for one person to take on big obligations in secret.

Visibility and Security

Formalizing roles tends to lead to more regular sit‑downs around real numbers. Many advisors push for monthly or quarterly “kitchen table reviews” where both spouses look at:

- Milk income and any other revenue.

- Feed, vet, labour, and energy costs.

- Repairs, fuel, and maintenance.

- Debt payments—principal and interest.

- Capital plans for the next 6–12 months.

When both names are on the ownership, and both are recognized decision‑makers, it’s natural for both to be in these conversations. Over time, that shared visibility makes it less likely that a bad line of credit, a missed payment, or a looming refinancing blindside anyone.

From a personal security standpoint, the spouse who used to be “just helping” now has documented ownership, a wage, or both. That matters for their retirement, their access to benefit programs, and how the next generation sees their role.

When adult kids see both parents’ names on ownership documents, they naturally include both in conversations about expansion, robots, beef‑on‑dairy, and succession. The paperwork doesn’t create respect, but it helps lock the reality into place.

When You’re Coming to This Late

A lot of you reading this have been married 25 or 30 years and have never had this conversation. You might be thinking, “We’ve made it this far. Is there any point now?”

Earlier is easier. But late is still a lot better than never.

Late‑Stage Adjustments That Still Help

Even if you’ve been farming as a sole proprietor for decades, there’s usually room to improve the picture:

- Shift into a formal partnership and bring your spouse in as a partner.

- Incorporate and issue shares to both spouses where it makes tax and transition sense.

- Put a wage around the work your spouse is already doing.

Advisors can help you:

- Put realistic values on land, quota, cattle, and equipment.

- Decide how to recognize past “sweat equity” in ownership going forward.

- Use tax tools and rollovers to avoid triggering big tax bills when you move assets into a new structure.

- Set up a more realistic income split that matches who is actually working in the business.

Farmers who’ve gone through this often describe it as a winter project: a handful of focused meetings, some back‑and‑forth on drafts, and professional fees that hurt a bit but are manageable relative to the value of the place and the stress it takes off the table.

You generally can’t rewrite history—claim wages that were never paid or pretend you’ve always been a partnership on past tax returns. And once divorce is already in play, judges in Ontario or U.S. states will look very closely at last‑minute structural changes, especially if those moves look like an attempt to dodge equalization or marital‑property rules.

When Lawyers Are Driving the Bus

Once a separation or divorce is properly underway, your room to manoeuvre shrinks fast.

In Ontario, judges apply the Family Law Act equalization rules, decide whether an unequal‑division claim has merit, and weigh unjust enrichment and constructive trust arguments based on the evidence. Outcomes at that point depend heavily on documentation and case law. In U.S. states, courts lean on the title, state law definitions of marital property, and any existing agreements.

At that stage, “we always treated it as ours” doesn’t carry nearly as much weight as people assume. We tell ourselves that trust is enough. The law, frankly, doesn’t care about that part. As one Ontario farm‑law specialist told a producer group, courts don’t divide trust; they divide property and documented entitlements.

That’s why some lenders, extension services, and succession programs—including FCC’s transition resources in Canada and Purdue’s workshops in the U.S.—now treat formal structures around spousal roles as part of basic risk management, not just something to think about when a marriage is already in trouble.

Real Farms, Real Women, Real Outcomes

To keep this grounded, it helps to look at how this plays out on actual dairies, not just in spreadsheets and court documents.

Sarah Sache – Fraser Valley, British Columbia

In the Fraser Valley—one of the highest land‑value dairy regions in North America—Sarah and Gene Sache, along with Gene’s brother Grant, run West River Farm near Rosedale. They milk a few hundred Holsteins and crop a relatively modest acreage in a very quota‑tight part of the valley. BC Dairy and Country Life in BC profiles have highlighted strong herd management, including solid butterfat performance where every kilogram of quota counts.

Sarah came into dairy from a business background and ended up managing the farm’s financial side—bookkeeping, cash flow, lender relationships, and regulatory paperwork. In 2018, she noticed there were no women on the BC Dairy board and decided that it needed to change. She ran, won a seat, later served as vice‑chair of BC Dairy, and now sits on the board of Dairy Farmers of Canada.

She’s talked openly about how intimidating that first board meeting felt—right down to not knowing where to sit—but also about realizing policy needed people who understood both the parlour and the balance sheet. Since she joined, she’s noted that more women have stepped into BC Dairy board and committee roles, broadening who shapes quota policy, promotion, and producer support. On her own farm, her role is formal, visible, and clearly tied to business decisions. That’s not just good optics; it’s good governance.

Kim Korn – Idaho

In Idaho, Kim and her husband run a relatively small dairy at Terreton. Their Korn Dairy herd has been recognized as a “small but mighty” operation in regional coverage. Dairy Farmers of America named Korn Dairy its 2019 Mountain Area Member of Distinction, and industry newsletters have highlighted their quality awards and consistent milk performance.

Kim serves as a board member for Dairy West, representing Idaho producers at the regional level. Industry profiles also note that she has taken on leadership roles in national dairy promotion and policy discussions through boards such as the National Dairy Promotion and Research Board and through her involvement with national checkoff organizations.

Profiles credit careful milking routines, parlour sanitation, and strong fresh-cow management as key reasons their somatic cell counts remain low, and their milk quality remains high. Here again, a relatively modest‑sized herd that treats the spouse as a formal manager and leader ends up punching above its weight on quality, reputation, management, and influence.

Martha and Stephen Kaaria – Meru County, Kenya

In Meru County, Kenya, Martha and Stephen Kaaria started with two cows and modest yields. Volunteers with Veterinarians Without Borders–Canada and their local co‑op, Meru Dairy, offered training on mastitis control, reproduction, nutrition, cow comfort, calf care, and basic farm economics.

Before training, peak production on their farm averaged around 14 litres per cow per day. Roughly six months after they started applying what they’d learned—better milking hygiene, improved ration balancing, more focus on cow comfort and fresh cow management—peak milk per cow jumped into the 18–25 litre range. They also started making maize silage, changed their cropping plans, and bought more land for forage. Those changes improved their food security and allowed them to spend more on their children’s schooling and health.

Crucially, Martha isn’t described as “helping.” VWB–Canada materials present her as a farmer and co‑decision‑maker. Different continent, different scale, same pattern: when women’s roles are central and formal, performance and resilience tend to improve.

| Farm | Location | Legal Structure Chosen | Implementation Timeline | Key Outcome |

| River Ranch Dairy | Idaho, USA | Limited Liability Company (LLC) with equal spousal ownership shares | 18 months (legal + financial restructuring) | Credit access improved; both spouses on loan covenants; succession plan pre-filed with county |

| Kaaria Family | Kenya | Registered family partnership with documented land + income rights for women | 24 months (included land title clarification) | Women’s enterprises showed 4.12-point lower default rate; farm productivity increased 22% post-formalization |

| Common Barrier Overcome (Both) | N/A | Cultural resistance: “Why fix what isn’t broken?” | Required external mediation (lawyer + accountant for River Ranch; NGO facilitator for Kaaria) | Both families now use formal ownership as competitive advantage in credit markets and succession planning |

Dairy Succession Planning: What This Actually Means for Your Operation

How you handle spousal roles over the next decade is going to shape who’s still milking, who owns the assets, and who has a voice in the industry.

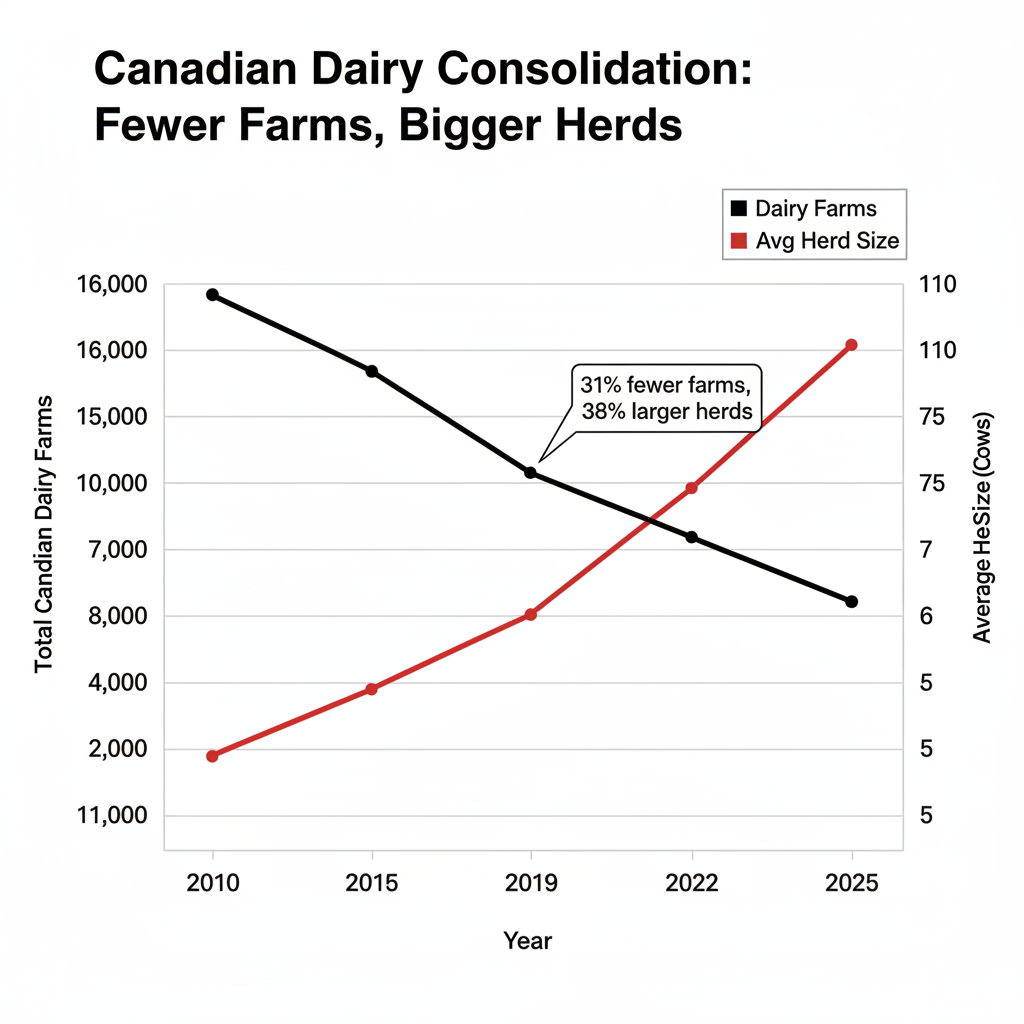

Under Canada’s quota system, a large share of your balance sheet is in land and butterfat quotas. From 2014 to 2024, the number of dairy farms declined from 12,007 to 9,256—about a 2.6% average annual drop—while total dairy farm cash receipts rose from roughly $6.1 billion to $8.9 billion. Average farm milk price per hectolitre climbed from about $81.79 to $97.38 over that same period. That’s fewer farms, bigger asset bases, and more milk per farm. [Source: Canadian Dairy Information Centre, 2024.]

Despite the drop in farm numbers, total milk production increased from 78.26 million hectolitres in 2014 to 96.61 million hectolitres in 2024—about a 23% jump. Productivity increased even as farm numbers declined. [CDIC 2024.]

That makes equalization and buy‑outs even more stressful relative to cash flow—especially in high land‑value regions like the Fraser Valley and parts of Quebec, where on‑paper wealth can dwarf available cash or operating credit.

In fluid/component markets like the U.S., you’ve got more price volatility and a different asset mix, but the same basic pinch: a lot of wealth on paper, heavy debt and capital needs, and not a lot of slack if you suddenly have to carve up equity under court timelines.

If more farms treat this as risk management, not “nice‑to‑have”:

- Succession runs smoother. When both spouses’ roles and ownership stakes are documented, it’s easier to design transitions that feel fair to farming and non‑farming kids and still keep the operation viable.

- Divorce doesn’t automatically equal liquidation. Clear ownership and buy‑sell mechanisms give families more options to keep cows milking during a separation, rather than dumping everything at a bad moment.

- Businesses get more resilient. If the patterns in empowerment research and Root Capital’s portfolio show up in dairy—even partly—then more women in formal leadership tend to align with steadier revenues, more cautious borrowing, and better risk planning.

- Leadership tables get stronger. When women move from “office help” to recognized co‑managers or partners, they bring real‑world, fresh cow management, labour, finance, genetics, and marketing experience into co‑op and boardrooms that badly need it.

If most farms keep relying on trust and habit:

- Succession logjams keep clogging the pipeline. Transition programs and lenders already talk about a “succession challenge” driven by aging operators and limited planning. Leaving spousal roles informal just adds another knot when it’s time to decide who runs and who owns what.

- We keep hearing quiet hard stories. Long‑term contributions don’t always translate into proportional claims on farm assets when everything rests on equalization formulas and title. Those stories may not make the local paper, but they’re in every coffee shop.

- Consolidation keeps nibbling away at family herds. CDIC data already shows fewer dairy farms and larger average herds, even as production grows. When otherwise viable herds are sold under pressure—divorce, succession fights, estate disputes—the buyers are often expanding neighbours or multi‑site outfits. There’s nothing inherently wrong with scale, but if the trigger is preventable structural risk, that’s a very expensive way to avoid some paperwork.

Here’s a quick “what this means” snapshot by situation:

- Under ~100 cows with one spouse doing books + calves + fresh cows: Start by tracking hours and putting a realistic job description and wage on that work. Then talk to your accountant about whether a simple spousal partnership makes sense in your tax context.

- 100–300 cows, or already incorporated/considering robots or a new parlour: You’re in the zone where share structure, shareholder agreements, and formal spousal roles can make or break a future buy‑out or transition. Make sure both spouses are listed as owners and signatories, not just for chores.

- Adult kids in the barn and tension about “who gets what”: Treat formalizing spousal roles and expectations as urgent, not something for “after harvest.” Involve the next generation in understanding who owns what, who does what, and how spouses fit in going forward.

What This Means for Your Operation

Strip away the gender and the law talk, and this comes down to three simple questions for your own yard:

- Who actually keeps this place running, day in and day out?

- What would it cost to replace them if they walked away tomorrow?

- Does your paperwork—and your paycheques—reflect that reality?

If the honest answer to #3 is “not even close,” then you’ve got some work to do.

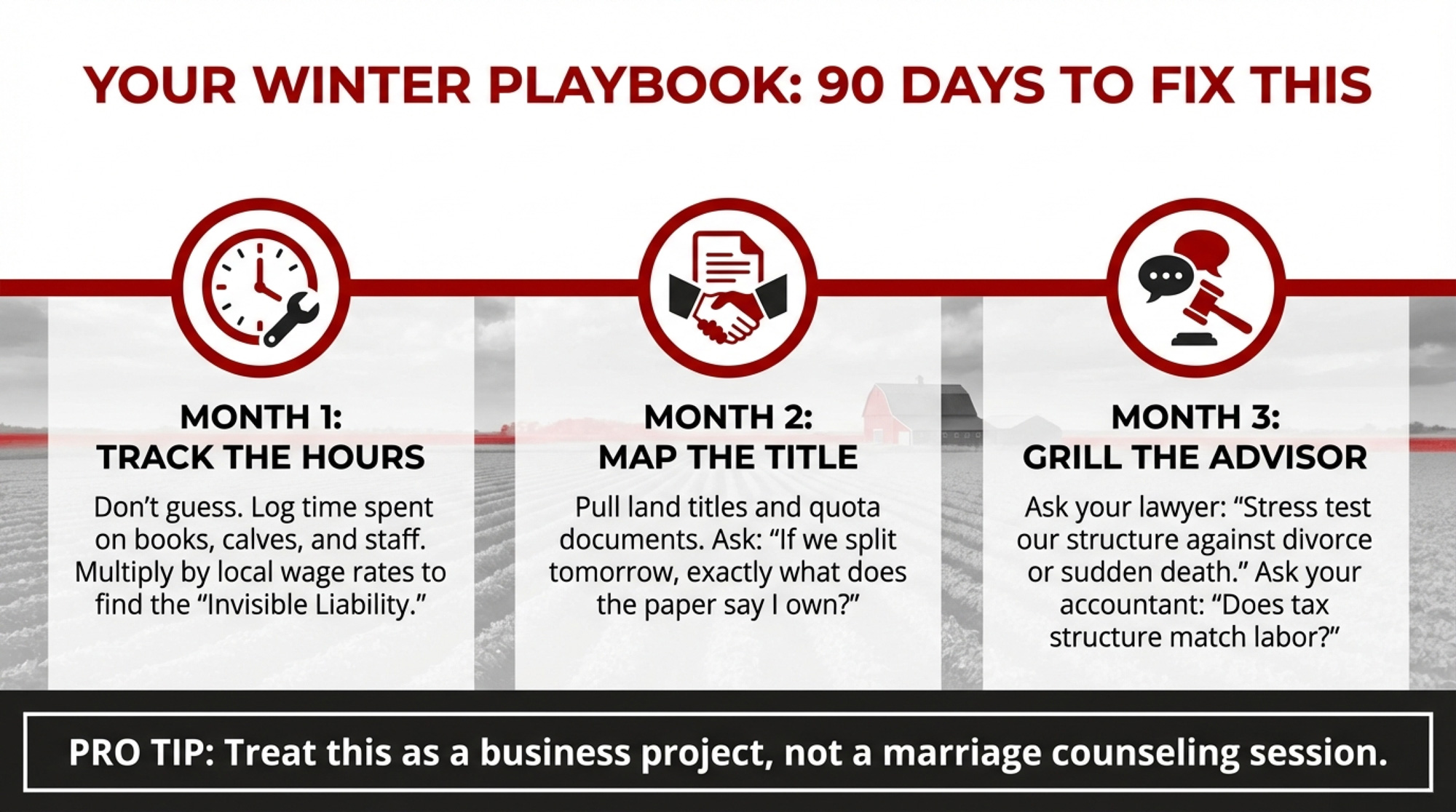

What You Can Actually Do This Winter: A Practical Playbook

Here’s what you can realistically do in the next 12 months, even with everything else on your plate—fresh cow follow‑up, feed costs, labour headaches.

1. Put Rough Numbers on Invisible Work

Over the next month or two:

- Ask your spouse to track the hours they spend on bookkeeping, HR, calves, heifers, and fresh cow checks.

- Pull local job postings for farm bookkeepers, office managers, or calf/youngstock managers and note wage ranges.

- Multiply those hours by realistic pay rates to get a ballpark replacement‑cost number.

You’re not putting a price on your marriage. You’re giving your business a clearer picture of how much unpaid labour it’s quietly leaning on, so you can judge risk and fairness with open eyes.

2. Map Who Owns What and Who Gets Paid

Gather the basics:

- Land titles and mortgage statements.

- Quota or pooling documents.

- Loan and lease agreements.

- Any partnership or corporate records you already have.

- Last year’s tax returns.

Then sit down with your accountant or lawyer and ask three blunt questions:

- Who legally owns what on this farm right now?

- If we had to divide this tomorrow under our province’s or state’s rules, what would that look like on paper?

- How is farm income currently split between us on the tax return, and does that reflect reality?

You might not like all the answers. At least you’ll know the starting point.

3. Grill Your Advisors About Structure

Once you know where you stand, take it a step further. Ask:

- Given how we actually work, would a spousal partnership, adjusted share structure, or clean employment agreement be the best first move for us?

- What are the tax implications—good and bad—of each option for the next 5–10 years?

- If one of us died, became disabled, or if we separated, how would this structure actually behave?

For small to mid‑sized dairies, shifting into a partnership or tightening up shares can usually be done in a few focused meetings over a winter, with professional fees in a “painful but manageable” range relative to your asset base. Larger and more complex herds will spend more, but still usually less than the cost—financial and emotional—of a messy breakup or forced sale.

If your advisor brushes off these questions or can’t explain your exposure in plain language, treat that as a red flag. It may be time to get a second opinion from someone who understands the legal structure of a family farm and dairy economics.

4. Bring the Next Generation Into the Picture

If your adult kids or in‑laws are already part of the operation—milking, cropping, managing fresh cows, or running calves:

- Sketch a simple diagram of who owns what and who does what today.

- Ask them how they see fairness and risk for themselves and their partners.

- Consider attending a succession‑planning workshop together. FCC offers transition programming in Canada, and Purdue Extension and others do the same in the U.S., often with content on family and spousal roles.

Younger farmers have seen enough neighbours get burned that they’re often more comfortable with formal agreements—and even with prenups—than their parents. That’s not a lack of trust. It’s respect for what’s at stake.

5. Treat This as Protection, Not Accusation

How you talk about this around the table is as important as what you do on paper. Families that handle it well tend to use language like:

- “We insure our barns and parlours. This is how we insure our relationships and our business.”

- “We’re just writing down what we’ve really been doing for years.”

- “This protects all of us—us, our kids, and the farm.”

If you do nothing else this winter:

- Map who owns what and who does what.

- Ask your accountant and a farm‑literate lawyer to show you what divorce, death, or disability would look like on paper under your local rules.

- Decide together whether you’re okay with that picture—or whether it’s time to change it before the next big life event forces your hand.

For more help, look at Farm Credit Canada’s transition resources, Canadian Bar Association guides on family farm succession, and Purdue Extension’s succession‑planning materials. They’re not a replacement for personalized advice, but they’re a good way to get the conversation started and to know what questions to ask.

Key Takeaways

- Trust isn’t a legal structure. Courts don’t divide trust; they divide property and documented entitlements. If your spouse’s role isn’t on paper, the law may treat them like a helper, not a co‑owner.

- Invisible work is a real risk. If your spouse walked away tomorrow, you’d probably have to hire at least one person—maybe more—to cover what they do. Start tracking that work and put a realistic value on it.

- Formal roles improve resilience. Research from WEAI‑based studies and Root Capital shows that when women have real authority and access to resources, farms and agribusinesses tend to be more stable and less risky.

- Structure choices have trade‑offs. Partnerships are simpler but offer fewer tools; corporations add complexity but open up more tax and transition options. The right mix depends on your size, region, genetics strategy, and goals.

- You don’t have to fix everything at once. Start with what’s most out of line with reality—usually the spouse doing major management work with no wage or ownership—and build from there.

The Bottom Line

At the end of the day, formalizing women’s roles doesn’t suddenly give anyone new instincts in the barn. The same person will still know which fresh cow is most likely to slip into ketosis, or which heifer is going to stir up every group she’s in.

What it does change is who’s recognized—by the law, by the bank, and by the next generation—as a full partner in those decisions and in the future of the herd. Either you decide how your spouse’s role shows up on paper, or your local statute and a judge will make that call for you when something breaks. One path’s uncomfortable. The other can cost you the farm.

When your kids look back in twenty years, do you want them to say, “That’s when we finally put on paper how Mom kept this place running,” or “That’s when the court told us who really owned the farm”?

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Only 16.5% of Dairy Farms Make It to the Third Generation – The Succession Decisions That Stop a Buyout from Killing Your Herd – Gain a battle-tested roadmap for transitioning your operation from management to ownership without triggering a family buyout. This guide reveals how to stress-test your advisors and document leadership milestones that keep your equity intact.

- The Real Reason Dairy Farms Are Disappearing (Hint: It’s Not About Better Farming) – Secure your future by understanding why market leverage and price transparency now dictate survival more than top cow performance. This investigation arms you with the strategic benchmarks required to navigate the industry’s aggressive consolidation curve.

- Four Farms Exit Daily: The $100K Decision Reshaping Dairy Survival – Capture over $100,000 in new annual revenue by pivoting your bottom-end genetics toward high-value beef-on-dairy contracts. This analysis breaks down the disruptive math that allows savvy managers to outpace consolidation and secure a permanent competitive advantage.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!