400 dairies became 3,176 warehouses. Before you face that math, see how one California dairy valley made its hardest choice.

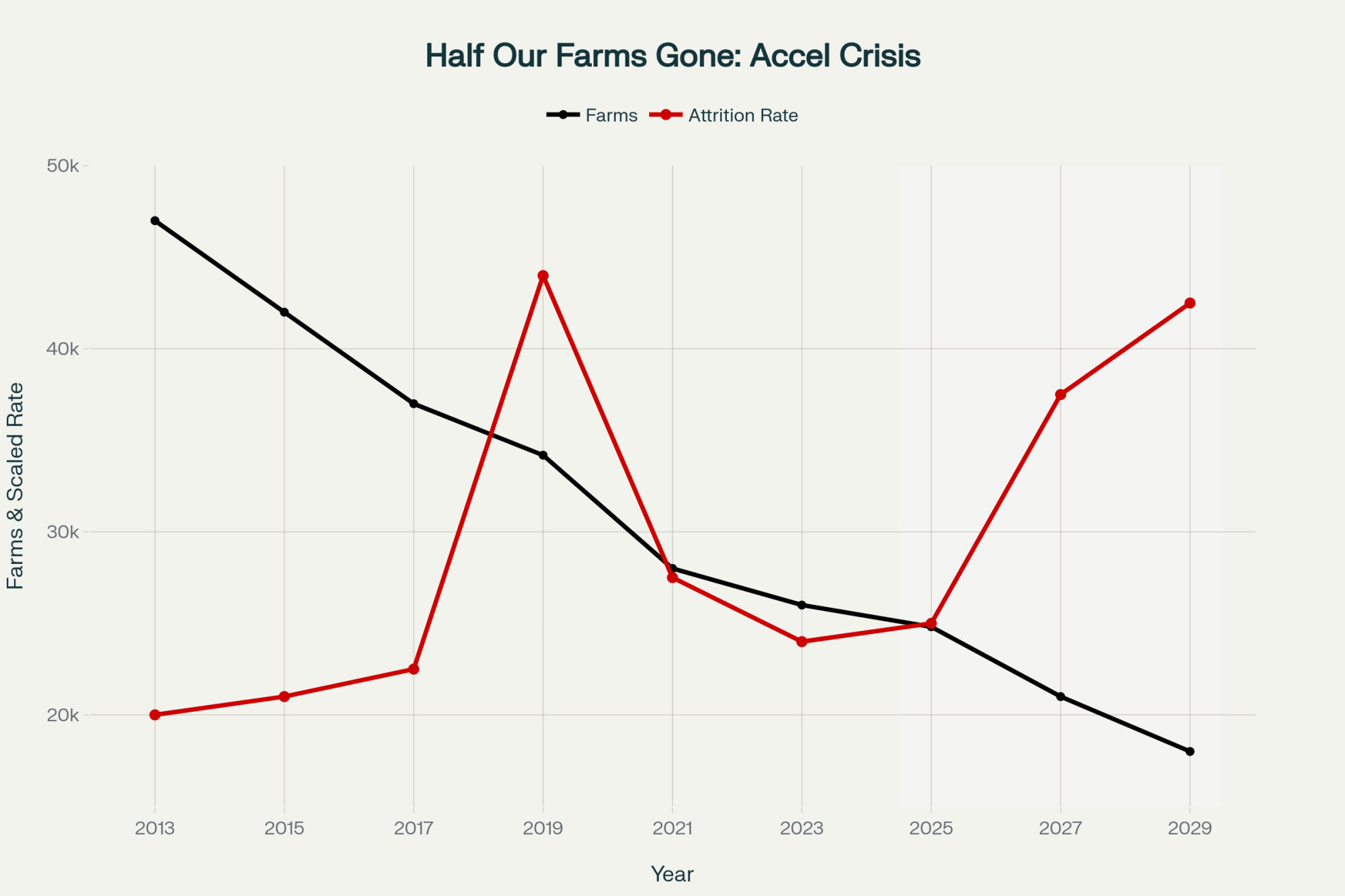

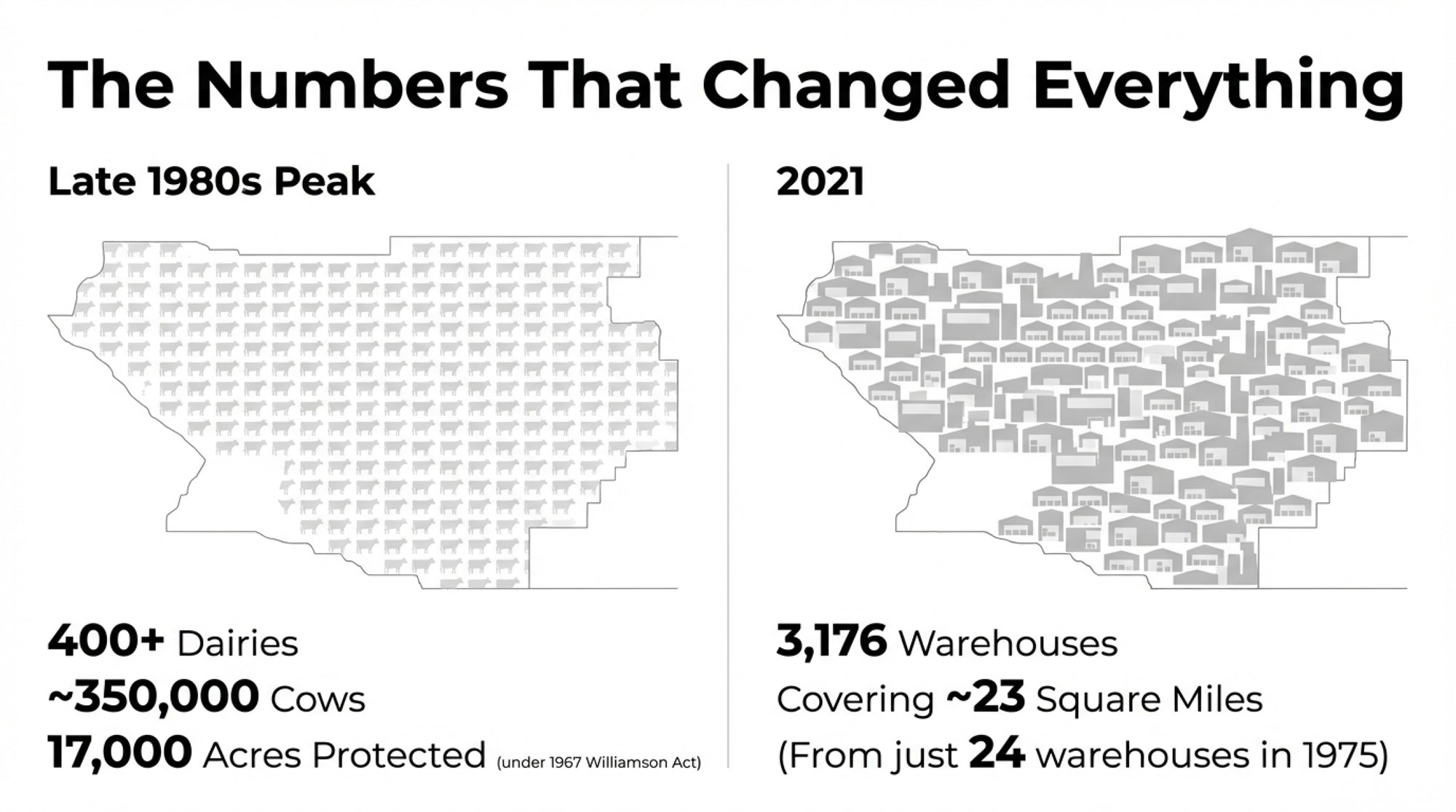

Executive Summary: At its peak in the late 1980s, California’s San Bernardino County Dairy Preserve around Chino and Ontario covered roughly 17,000 acres, with over 400 dairies and 350,000 cows producing most of Southern California’s milk. By 2021, logistics growth had turned much of that “dairy valley” into an industrial landscape, as San Bernardino County’s warehouses expanded from 24 in 1975 to 3,176, covering about 23 square miles—including former preserve land. This article traces how families like the Van Leeuwens, Alta Dena’s founders, and Geoffrey and Darlene Vanden Heuvel of J & D Star Dairy navigated that shift, balancing regulatory pressure and neighbor conflicts against rapidly rising land values and multimillion‑dollar buyout opportunities. It follows the northward move of many herds to Central Valley counties such as Tulare and Merced, now among California’s leading dairy counties by cow inventory and milk sales, and shows how the region’s milk production footprint changed without the people or their values simply disappearing. For today’s producers facing their own land‑value wake‑up calls, the piece offers a practical kitchen‑table framework: put your equity on paper, sketch three realistic paths (stay and reinvest, stay and scale back, or plan an exit), and ask which choice your family will be most at peace with five years from now. Above all, it argues that legacy in dairy isn’t defined only by keeping a specific farm operating, but by the courage to protect your family and carry forward the values you built in the barn—whether that’s on the same acres, in a new county, or in a different role in the industry.

I still remember the first time I watched her hesitate at that kitchen table.

The documentary about the San Bernardino County Dairy Preserve had just started. On paper, it was a history lesson: roughly 17,000 acres brought under California’s Williamson Act in 1967, more than 400 dairies and about 350,000 cows at the peak, supplying most of Southern California’s milk. The numbers lined up neatly on the screen.

But the moment that changed everything for me wasn’t a statistic. It was one daughter trying to talk about her dad.

She’s sitting at a table that looks like it’s hosted more milk checks, arguments, and late‑night coffees than anyone could count. In the film—shared by her family so people could understand what the preserve meant—she explains that her father grew up on São Jorge in the Azores. Out there, it was all pastures and cattle. Milking and raising animals were what he knew, so when he came to California, that’s what he did.

“It’s all pastures,” she says quietly, “so that’s what my father grew up doing—was milking the cows, raising cattle.”

And then she stops.

It’s barely half a second. Her eyes drift down, her fingers tighten a little on the mug, and there’s this small, fragile silence you can feel right through the screen. What moved me most was that silence. In that breath, you can hear everything her father carried: a young immigrant stepping into a strange country, barns rising on leased land, cows that paid the bills and anchored the family, a valley that once smelled like silage and warm milk—and the slow realization that the world around those barns had changed.

If you’ve ever looked across your own yard and wondered what happens if the land under your freestalls becomes worth more to somebody else than your milk will ever justify, you already know this story is closer to home than any map shows.

No One Thought This Dirt Would Be a Dairy Giant

No one driving past that dusty patch of southern California in the 1940s would’ve guessed it would become one of the most intense dairy regions in the country.

After World War II, waves of farm families came into places like Chino and Ontario. Dutch and Portuguese names began appearing on mailboxes and milk tankers. Historical accounts show Azorean Portuguese immigrants climbing the ladder one step at a time: first as hired hands, then as herdsmen, then as partners, and finally as owners. There were no consultants or five‑year plans—just people who knew cows and were willing to work.

They built more than rows of stalls.

Community histories describe how those families rooted D.E.S. halls and Holy Ghost festas across California’s dairy regions. You can almost smell the smoke from the churrasqueira and hear the clatter of plates as you read them: tents sagging over rough tables, kids in red sashes weaving between chairs, elders arguing in Portuguese about which donated animal was the best offering that year. No one’s marketing budget sponsored those gatherings. They were paid for out of parlors up and down the valley.

Then there were families like the Van Leeuwens. A Los Angeles Times feature tells how Bill Van Leeuwen’s grandfather left the Netherlands in the 1920s and started a dairy in Paramount with about 60 cows, all milked by hand. Later, Bill’s father bought a 17‑acre dairy in Norwalk in 1945, grew it to roughly 180 cows with mechanical milking, and watched houses press in tighter every year. When the city got too close, they sold that Norwalk farm in 1957 for about $17,000 and moved again—this time to Chino, where the land was cheaper and zoned for dairies.

On a timeline, that looks straightforward: buy, build, sell, move. On the ground, it’s a lot messier. It’s loading your best cows onto someone else’s trailer at an auction you never wanted to hold. It’s kids landing in new schools and trying to explain why their boots smell the way they do. It’s lying awake at night, wondering if uprooting everyone—again—was a brave move or a terrible mistake.

Against all odds, families kept choosing to move when staying put stopped making sense. Not because they weren’t scared. Because they were, and they did it anyway.

The Preserve That Was Supposed to Keep Them Safe

The preserve was supposed to be the part of the story where the pressure finally eased.

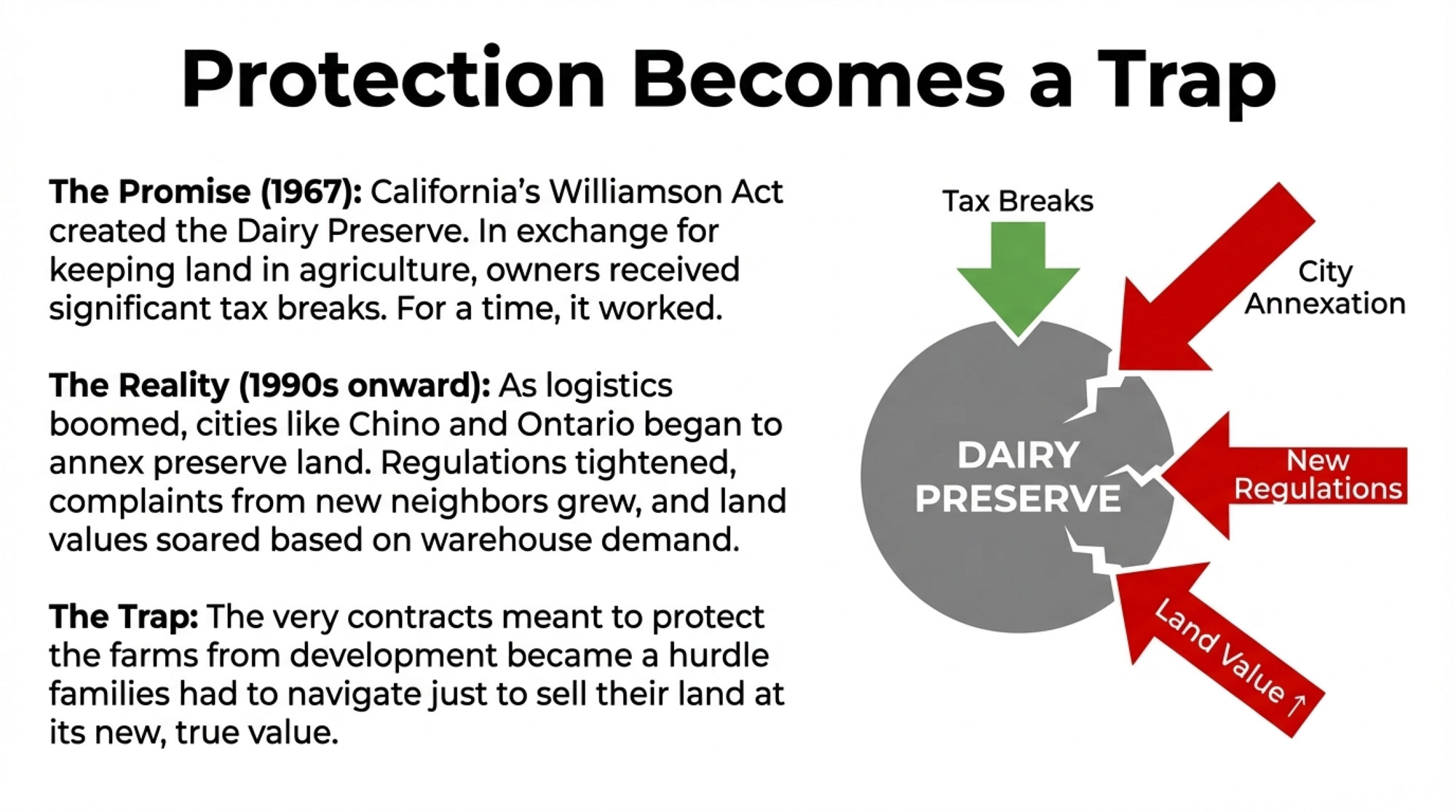

In 1967, under California’s Williamson Act, San Bernardino County created what became known as the San Bernardino County Dairy Preserve. Owners who agreed to keep their land in agriculture for ten‑year stretches got a tax break. About 17,000 acres around Ontario and Chino were drawn into a zone where dairies were not just tolerated—they were officially wanted.

For a while, that line on the map did exactly what it was meant to do.

By the late 1980s, that preserve held more than 400 dairies and around 350,000 cows, widely described as the largest single dairy concentration in the United States and the source of most of Southern California’s milk. A University of California report at the time described roughly 280,000 cows in about 300 herds across 20 square miles, with average herd sizes over 900 and nearly all of them family‑owned and managed.

Then the world outside the fence changed faster than the rules inside it.

PBS SoCal’s Earth Focus reporting and county data show how, starting in the 1970s and accelerating through the 1990s and 2000s, San Bernardino County became a logistics hotspot. In 1975, there were just 24 warehouses. By 2021, there were 3,176, covering about 23 square miles of what had once been open land. More and more of those roofs went up on former dairy ground, including pieces of the preserve.

Cities like Ontario and Chino annexed big chunks of that rural area as they expanded, pulling dairy land into city limits and long‑range development plans. At the same time, dairies in the preserve were wrestling with environmental rules, odor and dust complaints, rising costs, and the same milk price volatility everyone else knows.

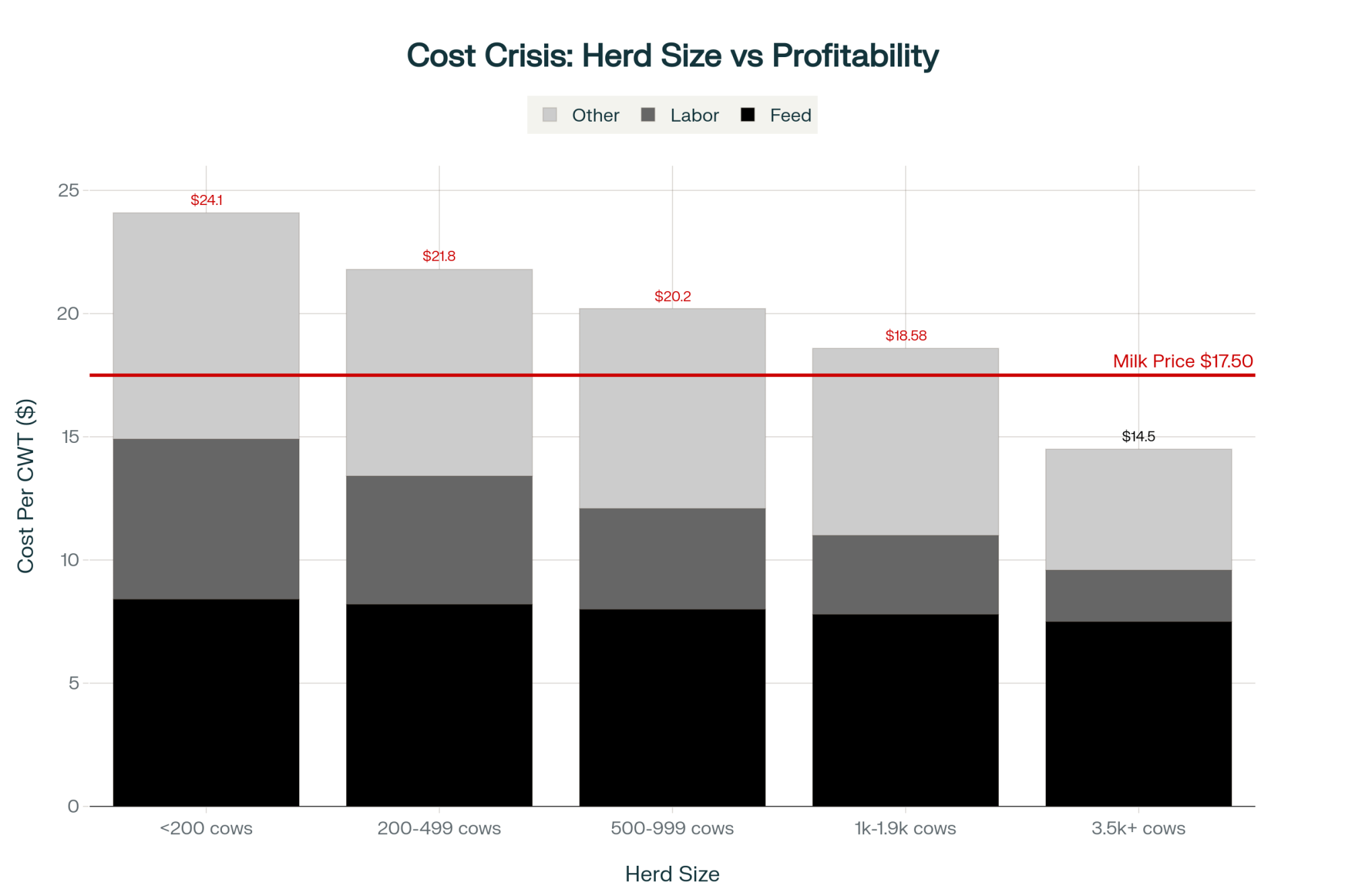

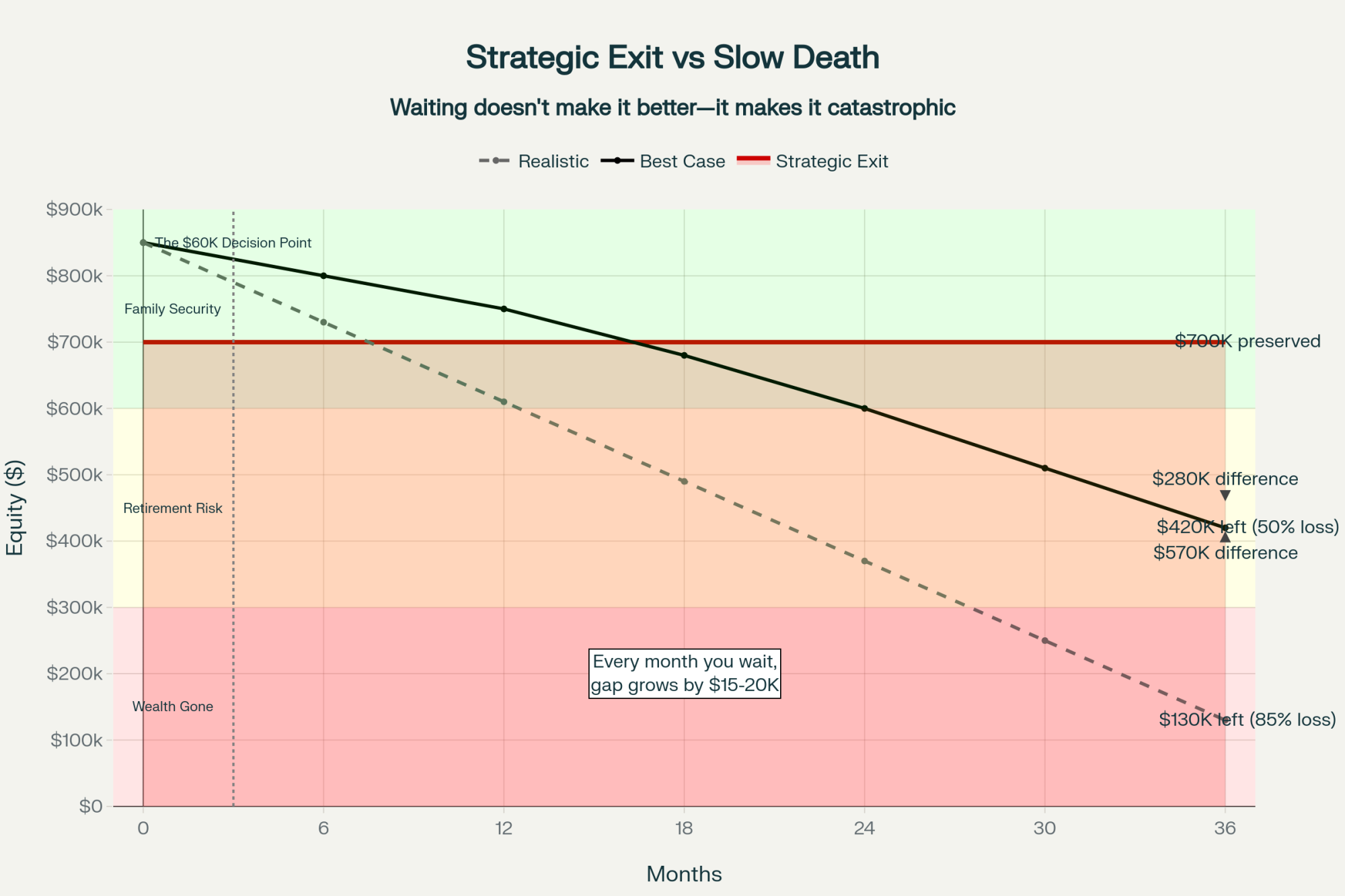

On the surface, some of those operations looked stronger than ever: bigger herds, better parlors, more milk shipped. Underneath, the math was bending. The ground under those freestalls suddenly carried a price tag driven more by warehouse demand than by milk checks, and the contracts that had once offered protection were now one more factor to navigate before a family could even think about selling.

The fence that was drawn to keep the bulldozers out had quietly become part of the puzzle families had to solve just to protect themselves.

Standing in the Barn When It Starts to Feel Smaller

The call that changes everything doesn’t always come from a lawyer or a city planner. Sometimes it comes while you’re just standing in your own parlor.

Producers interviewed in planning documents and local reporting talk about that moment without always naming it. They had moved when the cities pushed in. They had signed onto the preserve. They had doubled down and built bigger. They had done everything they were told “serious” dairies had to do.

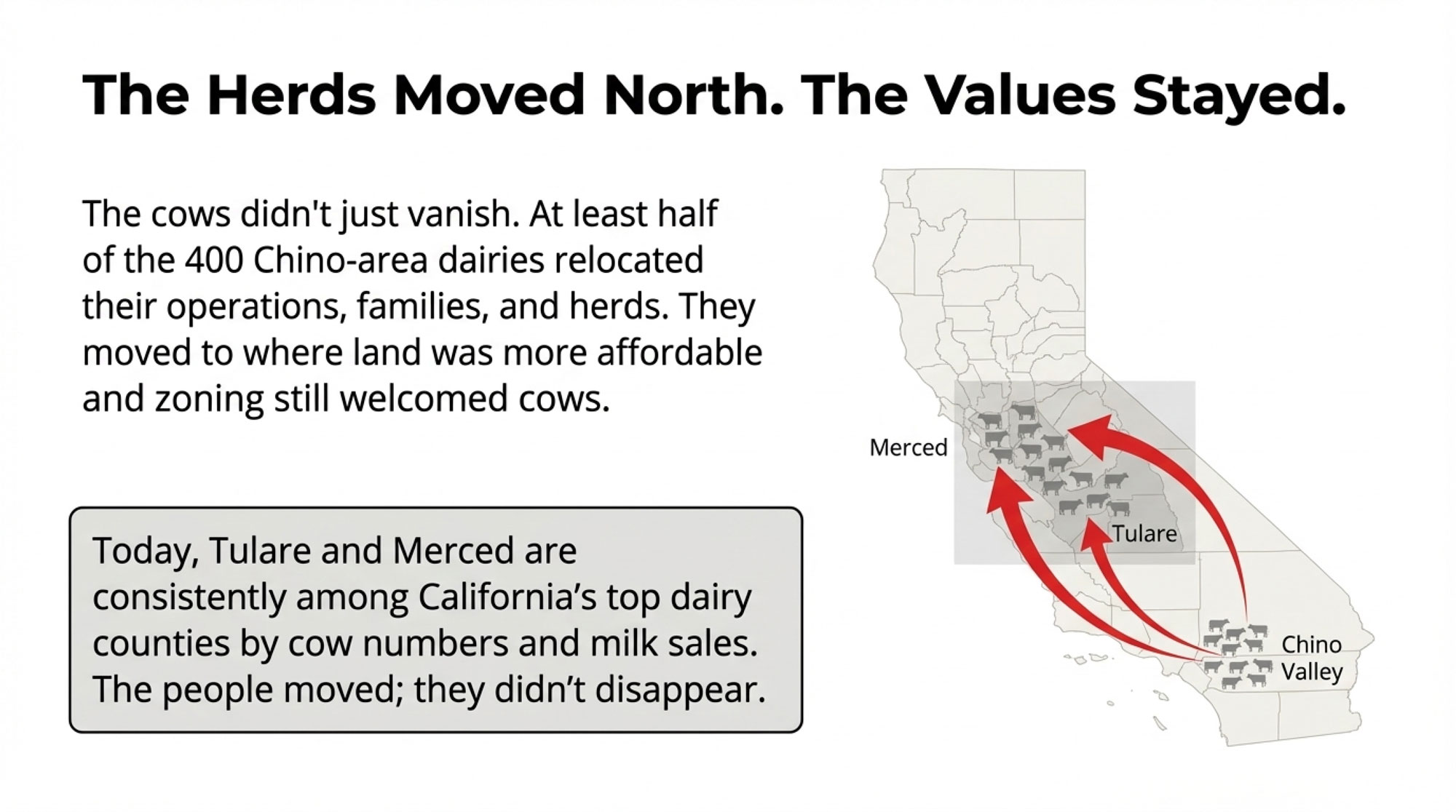

In 1993, San Bernardino County began formally phasing out the agricultural preserve. Over the years that followed, planning reports show that at least half of the roughly 400 dairies moved out, many heading for Central Valley counties like Tulare and Merced, where land was cheaper and zoning still openly welcomed cows. Others tried to hang on as long as they could.

Some of those who stayed told county officials and reporters something very simple: they didn’t want special treatment; they wanted the same right as any other landowner to sell their land at its true value when that was what their family needed.

Imagine finishing cleanup, leaning your arms on the pit rail, and realizing that on paper, your entire life’s work sits on land that’s suddenly worth more to a trucking company than your milk will ever justify—and knowing that the system built to protect you now plays a big role in how easily you can step away. That’s not just a business problem. That’s something that gets into your bones.

When your whole sense of self starts with “I’m a dairyman” or “I’m a dairywoman,” even letting the thought “Maybe we should sell” float across your mind for more than a second can feel like treason. Not against the land. Against who you’ve always believed you are.

When Neighbors You Trust Suddenly See Different Futures

The deepest cracks didn’t only come from policy or developers. They also ran right between neighbors who had once stood shoulder to shoulder.

As the county moved to unwind the preserve and cities annexed more land, dairy families found themselves standing on opposite sides of a line no one had deliberately drawn. In broad strokes, many older or smaller operations, worn down and boxed in, wanted the option to sell to developers at full value. Larger, heavily invested herds with newer facilities wanted the land to stay agricultural and the cluster intact.

Planning reports describe how some producers saw the preserve as some of the best dairy ground anywhere, and grieved the idea of losing it under concrete. Others looked at appraisals and felt that not being able to sell freely at those prices effectively pinned their families in a corner they hadn’t chosen.

Nobody in those meetings loved cows less than anyone else. They were just looking at the same valley from different kitchen tables.

“We Weren’t Forced Out. We Were Enticed.”

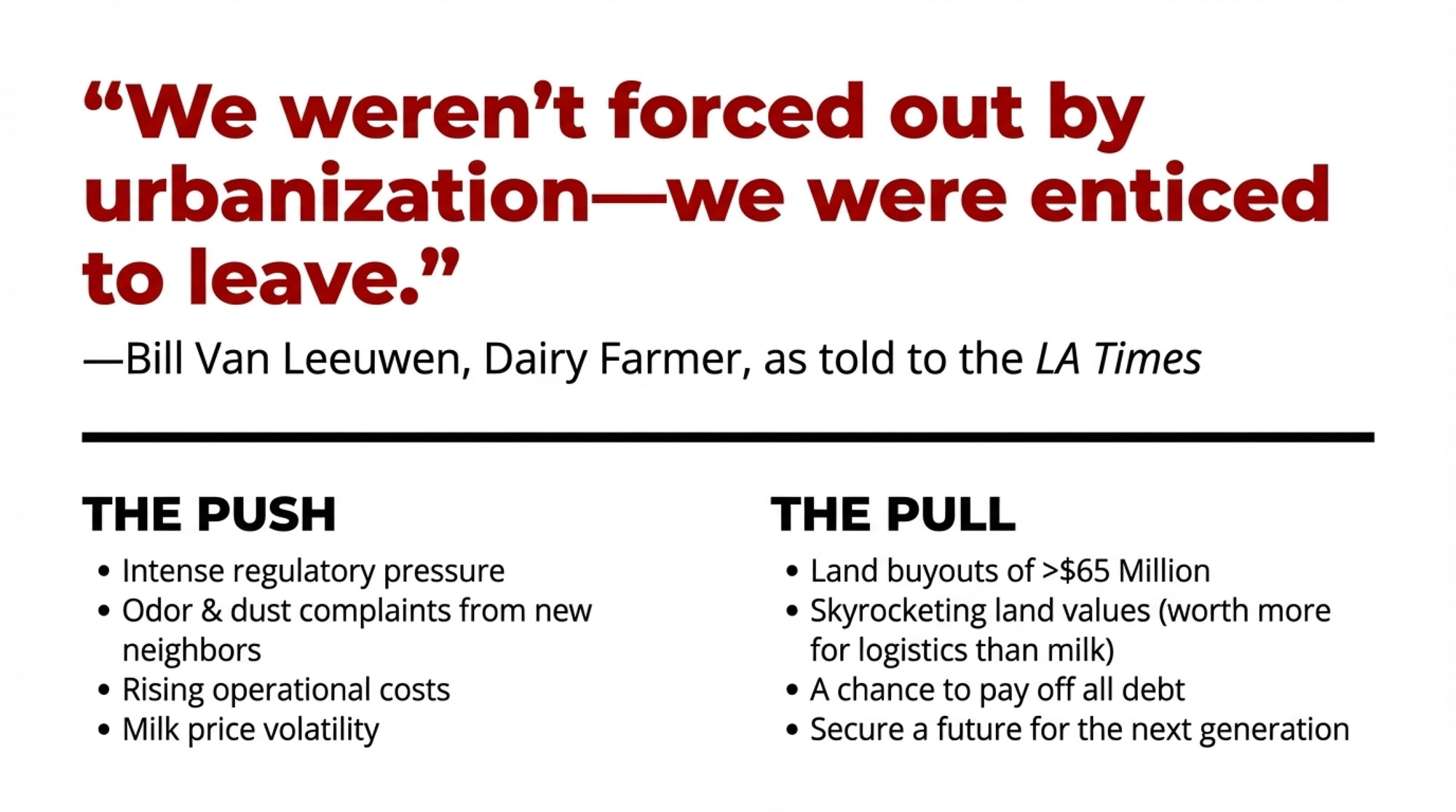

One line in this story still hits like a punch.

In a Los Angeles Times piece about the area’s dairies leaving, Bill Van Leeuwen said:

“Dairy farmers will say they were forced out by urbanization, but really, we were enticed to leave.”

He could have just said “forced out” and left it there. Urbanization, annexations, and changing rules absolutely pushed. But Bill knew there was another side to the ledger.

PBS SoCal and county documents spell out what was happening: as warehouse demand surged and land prices climbed, developers offered high purchase prices for dairy parcels. At the same time, San Bernardino County created mechanisms for early withdrawal from Williamson Act contracts and began auctioning county‑owned parcels, like the land under J & D Star Dairy. In 2014, that auction drew more than $65 million from warehouse and logistics buyers.

On one side: long days, regulatory pressure, neighbor complaints, aging bodies, and kids whose attachment to the cows may not look the same as yours. On the other: a cheque big enough to pay off debt, help children into their own futures, and maybe ease some of the strain.

Bill’s sentence doesn’t try to make anyone a hero or a victim. It simply admits that families were pushed and pulled at the same time. That honesty is part of what makes this whole valley’s story so powerful.

“Once the Dairies Leave, What Do You Do?”

Sometimes the most important question gets asked long before anyone’s ready to answer it.

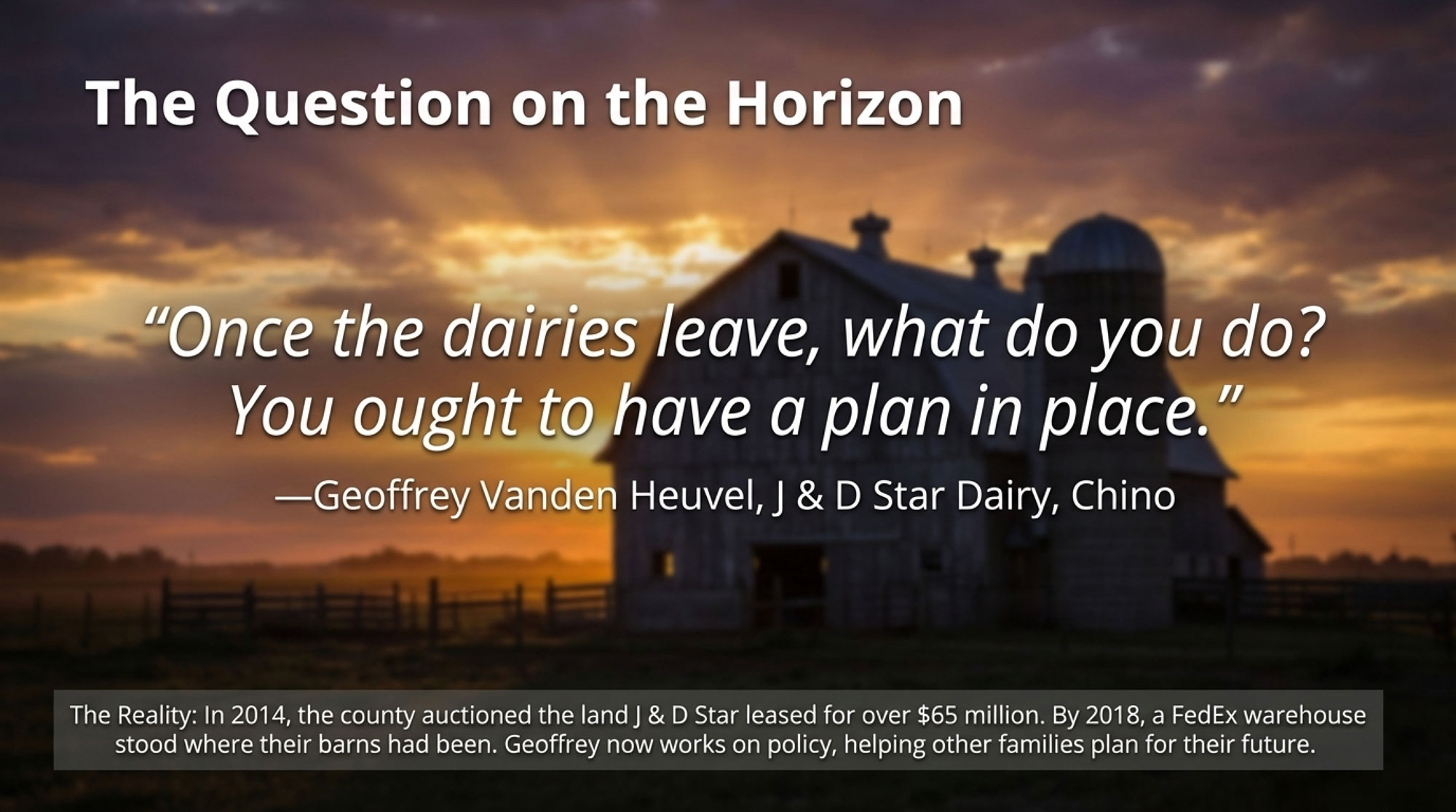

In archival footage tied to the recent documentary about the San Bernardino Dairy Preserve, Geoffrey Vanden Heuvel stands in front of J & D Star Dairy in Chino. He and his wife, Darlene, had built that dairy, on land leased from the county, into a notable family operation in the preserve.

Looking into the camera, Geoffrey says, “Once the dairies leave, what do you do? You ought to have a plan in place.”

At the time, that must’ve felt like talking about a storm still sitting on the far horizon. The preserve was still in place on paper. A lot of people didn’t want to imagine a valley without dairy barns.

But the record shows how accurate he was. San Bernardino County began phasing out the preserve in 1993. As years passed, many of the preserve dairies moved to Central Valley counties like Tulare and Merced, which have consistently ranked among California’s top dairy counties for cow numbers and milk sales over the past decade.

J & D Star stayed longer than most. Then, in 2014, the county auctioned the land it was leasing, and developers bought it as part of a package worth over $65 million. By 2018, PBS SoCal reports that a FedEx warehouse and a large parking lot sat at Merrill and Flight avenues, where J & D Star’s corrals and barns had stood.

Geoffrey didn’t simply disappear from the industry when the dairy closed. Today, he serves as Director of Regulatory and Economic Affairs for the Milk Producers Council, working on policy and economic issues that shape the future for other dairy families across California. The same man who said, “You ought to have a plan in place,” now spends his days helping others think ahead.

When a Founder Admits Grit Isn’t Always Enough

If you zoom out beyond the Chino preserve, another name keeps showing up in California’s dairy story: Harold Stueve.

The Los Angeles Times recounts how he and his brother Edgar founded Alta Dena Dairy in Monrovia in 1945 with 61 cows and a milk wagon. By the 1960s, they had grown it into one of the largest dairies in the world. When the family sold a majority interest in 1989, Alta Dena had annual sales of more than $125 million and over 70 family members working in the business.

Later, as legal battles over raw milk, regulatory scrutiny, and urban growth intensified around their operations, Alta Dena sold most of its Chino-area dairy land. On paper, it reads like just another corporate transition. When you look closer, you see decades of pushing, innovating, and eventually hitting constraints you can’t simply outwork.

Over the years, Harold acknowledged that there comes a point where you can’t keep a large dairy going if houses and schools completely hem you in. You need open ground, a supportive community, and workable rules. If those disappear, even the toughest operator runs into walls that grit alone can’t knock down.

Sometimes courage is setting your alarm for 3:30 AM for the thousandth day in a row. Sometimes courage is admitting that the rules have changed enough that the old plan can’t get you where you hoped to go.

The Questions That Decide Everything (and They Don’t Show Up on a Spreadsheet)

The biggest turning points in this story didn’t happen at county hearings or in courtrooms. They happened at kitchen tables like yours.

The kids finally fall asleep. The second milking is done. The only sounds are the fridge humming and someone turning pages in a stack of bills. Maybe there’s an appraisal in there. Maybe a letter from the lender. Maybe just your own notes with numbers you’ve run three times and still don’t like.

Somebody stares at the paper. Somebody else stares at the wall. Someone says, “We’re okay,” but nobody really believes it.

The details are different from farm to farm, but the same questions keep trying to surface—even if they first show up as half sentences and long pauses instead of clean bullet points.

What are we actually protecting here?

Not “the family farm” as an idea. This exact operation. These cows. This land. These loans. This level of stress on your body. These kids are watching you, trying to decide if this is a life they can see themselves in.

Sometimes the moment that changes everything isn’t when some letter shows up in the mailbox. It’s when someone finally whispers, “Are we protecting the farm, or are we protecting our family?” and nobody rushes to shut it down.

Five years from now, what decision will we be most at peace with?

Nobody typically says it that neatly across the table. It comes out as, “I can’t keep this up forever,” or “If we walk away, who am I?”

But underneath, that’s the question. If you could look back from five years ahead, what would you be most grateful you did now? Pushed through one more round of changes? Took a serious offer while it was on the table? At least they laid every option out honestly and listened to each other?

There’s no path with zero regret. The real choice is which regret you can live with.

What does legacy really mean to us?

Is legacy only an unbroken line of your farm name on this specific piece of land?

Or is legacy your kids carrying your values—work ethic, care for animals, honesty—in whatever work actually lets them build a life? The historical record from the Chino milk shed shows families moving their herds to Tulare or Merced to keep milking, while others stepped into different roles within the industry. The barns changed. The values didn’t.

Are we still running this farm, or are we just holding a very expensive ticket in a game we no longer control?

When you sketch out your net worth and realize most of it is tied up in land whose price swings more with zoning decisions, warehouse demand, or policy than with what you ship in the tank, that’s a different kind of risk. For some families, that risk still feels worth it. For others, it feels like a clock ticking in the background.

There’s no single right answer baked into these questions. The only real mistake is refusing to ask them because you’re afraid of where the conversation might go.

A Kitchen‑Table Playbook You Can Actually Use

This isn’t a mastitis protocol or a robot ROI spreadsheet. It’s simpler and, in some ways, harder. But if anything in the Chino story hits you in the gut, here’s a framework you can adapt to your own table.

1. Put your equity on paper—for yourselves.

Not a formal statement. Just an honest sketch. How much of your net worth is in cows, machinery, and working capital versus land and buildings? It doesn’t have to be down to the dollar. It just has to be real enough that everyone around the table can see its shape.

2. Sketch three paths, even if you hate all of them at first.

- One where you stay and reinvest: what would you actually change—facilities, herd size, contracts?

- One where you stay but intentionally scale back or shift direction.

- One where you sell or transition over a defined timeline—maybe to family, maybe not.

You’re not signing anything. You’re just admitting that these are the real options, not the ones you wish you had.

3. Ask the five‑year question out loud.

“If we look back from five years out, which of these paths will we be most at peace with—even if it’s hard in the short term?”

Let everyone answer from where they sit—owner, spouse, next generation. Don’t rush to smooth it over. Let there be a few uncomfortable silences. Sometimes that’s where the truth finally slips out.

You don’t owe social media or the neighbors a tidy narrative. You owe the people at that table your best effort at the truth.

What’s Left When the Barns Are Gone

If you drive through that valley today with no idea what it used to be, you’ll mostly see concrete and loading bays.

PBS SoCal shows how the J & D Star Dairy land, once home to corrals, lagoons, and barns, is now a FedEx warehouse and a large parking lot at Merrill and Flight avenues. The same reporting and county data map out thousands of warehouse roofs across roughly 23 square miles of what was some of the most productive dairy ground anywhere in the state.

In some of those industrial parks, bronze cow statues are standing in front of office doors—a nod to the cows that once lived there. To someone just passing through, it might look like a quirky design choice. To someone who grew up milking there, it probably feels more like walking into an empty barn and hearing phantom pulsators.

The cows didn’t all vanish; they moved. Industry data and USDA Census snapshots over the past decade consistently place Tulare and Merced among California’s top dairy counties for cow numbers and milk sales, reflecting the shift of herd concentration into the Central Valley.

Holy Ghost festas still pack D.E.S. halls in Portuguese communities, including in places tied back to the preserve story. The names on some of those banners are the same names that once hung over dairy lanes near Chino. Some of those families are still milking, just in different counties. Others are working in roles that keep them connected to cows and producers in new ways.

The valley’s role in the dairy map changed. The people who built it didn’t just evaporate.

If You’re Standing on That Edge Yourself

You might be nowhere near California. Your pressure might come from quota rules, a processor that’s gotten too big, labor you can’t find, interest rates that keep you up at night, or climate policy that makes your head spin. The details are different, but that feeling in your gut can be exactly the same.

If you’ve ever sat at your own kitchen table with a stack of envelopes, your stomach in a knot, and that little voice saying, “We can’t keep doing it like this forever,” then you are closer to those San Bernardino families than you might want to admit.

This story isn’t here to talk you into staying or to talk you into leaving. That’s not anyone else’s job.

What it can do is give you a few things their journeys made painfully clear:

- You’re not weak for questioning whether the current path still makes sense.

- You’re not a failure if, in your situation, protecting your family means exiting an operation your grandparents poured their lives into.

- You’re not alone if, some nights, the place that once held all your dreams now feels like it’s squeezing them.

The strength that comes through the Chino story isn’t just the toughness it took to build those dairies in the first place. It’s the quiet courage it took to keep going while the landscape and the rules shifted underneath them—and then, when the time came, to admit that the bravest move for their family might be a different one than they expected.

The Part of Your Legacy No One Can Pave Over

I keep going back to that woman at the kitchen table and that half‑second pause before she could talk about her dad.

He didn’t leave São Jorge, cross an ocean, and put his whole life into cows and concrete barns so his name would stay attached to one particular parcel of land forever. He did it to give his family a chance—to keep them secure and part of a community that knew their name.

For a long time, dairy was the best way he knew to do that. The barns, the cows, the milk checks—they mattered. They helped hold households and community institutions together in that valley.

But the legacy he left her didn’t live in a legal description on a deed. It lives in the way she carries his story, in the values and work ethic he passed on, and in her willingness to share that story so other families can see themselves in it.

Your legacy isn’t only the cows you milk or the acres that carry your name.

Your legacy is the courage to do what it takes to give the people you love a future they can live with—whether that means staying and reinventing your operation, moving and rebuilding somewhere that fits better, or blessing the next generation as they carry your values into a different part of the dairy chain or into something else entirely.

Sometimes that’ll mean doubling down: investing in cow comfort, air, and shade; tightening up decisions; bringing your kids into the real conversations instead of just handing them a pitchfork. Sometimes it’ll mean cheering them on as they walk into a feed lab, a vet clinic, or another barn with your lessons in their back pocket, not your name on their pay stub.

And sometimes, it might mean sitting at that same table that’s seen more milk checks than you can count and finally saying, with your voice catching just a bit:

“We can’t carry on this business the way it is, not here. And that’s okay. We’ll find another way.”

If you’re anywhere on that edge right now—half anchored in the life you’ve always known, half staring into a fog of what‑ifs—this story isn’t here to push you in either direction.

It’s here to give you permission to ask the hard questions, to listen to each other without flinching, and to remember something the Chino valley proved in its own hard way:

The barns may change. The land may change. The way we milk and get paid will keep changing, just like it did there.

But that quiet, stubborn determination at the core of this way of life—the part that keeps you getting up on the mornings when nothing on the ledger looks pretty—that’s yours. No auction, no zoning vote, no warehouse, and no milk price can ever take that from you.

Key Takeaways

- The numbers tell the story: At its peak, California’s Chino–Ontario dairy preserve held 400+ dairies and ~350,000 cows on 17,000 acres; by 2021, San Bernardino County’s warehouses had grown from 24 (1975) to 3,176, paving roughly 23 square miles—including much of that preserve.

- Pushed and pulled at once: As one longtime dairyman said, families weren’t simply “forced out by urbanization”—they were “enticed to leave” by land values that dwarfed what milk checks could ever justify.

- The herds moved, they didn’t vanish: At least half the preserve’s dairies relocated to Central Valley counties like Tulare and Merced, which now rank among California’s top dairy counties by cow inventory and sales.

- A kitchen-table playbook for today: If you’re facing land-pressure decisions, start here—put your equity on paper, map three paths (reinvest, scale back, or exit), and ask which choice your family will be most at peace with five years from now.

- Legacy isn’t acreage—it’s values: The Chino story proves that what you pass on isn’t a deed or a barn; it’s the courage to protect your family and carry forward what you built, wherever that takes you.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Decide or Decline: 2025 and the Future of Mid-Size Dairies – Gain the clarity needed to stop the drift and start leading. This guide delivers the hard financial benchmarks—from debt ratios to precision feeding ROI—that move mid-sized dairies from fatigue into a model of aggressive profitability.

- 2025’s $21 Milk Reality: The 18-Month Window to Transform Your Dairy Before Consolidation Decides for You – Identify the specific multi-family partnership and diversification models required to outpace market consolidation. This analysis exposes the shifting math behind the 600-cow dairy and reveals how to position your operation for the 2030 landscape.

- Revolutionizing Dairy Farming: How AI, Robotics, and Blockchain Are Shaping the Future of Agriculture in 2025 – Weaponize your legacy with Silicon Valley firepower. Gain a competitive edge by identifying the 2025 tech tools—from AI-powered genetic markers to autonomous milking—that slash labor costs by 70% and transform your herd into a high-precision profit engine.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!