The cows haven’t changed. The math has. Why good dairies are suddenly fighting to survive.

Executive Summary: Well-managed mid-size dairies are facing a reckoning that has nothing to do with their cows. As loans from the low-rate era (2015-2021) reset to current markets—the Chicago Fed shows operating rates now at 7.73%, nearly double what many locked in—debt service is jumping 25-30% overnight. For a 400-cow dairy with typical leverage, that translates to $120,000 in added annual costs before a single operational change. Here’s what catches producers off guard: even farms current on every payment can trigger technical default when covenant ratios slip due to rate-driven debt increases, not management problems. More than 1,400 U.S. dairies closed in 2024, per USDA—Wisconsin alone lost 400. The path forward requires calculating your true breakeven at new rates, engaging lenders proactively with specific proposals, and recognizing that planned transitions preserve far more family wealth than forced exits ever do.

I’ve been having a lot of conversations lately that start the same way. A producer messages me after seeing their repricing notice, and the story sounds remarkably similar each time.

Take Dave, a Wisconsin dairyman I spoke with. When he ran his numbers after getting the repricing letter on his real estate loan, he discovered his breakeven had jumped from $17.50 to $19.20 per hundredweight. Nothing about his 380-cow operation had changed. The cows were still averaging 78 pounds. His nutrition program was dialed in. His fresh cow protocols were solid, and his transition period management hadn’t slipped. But the math had fundamentally shifted.

“I’ve been through bad milk prices before,” Dave told me. “I know how to tighten things up when we’re looking at $14 milk. But this feels different. My costs went up $110,000 from a single letter, and there’s nothing I can do with the cows to fix it.”

What struck me about that conversation—and the dozens like it I’ve had since—is how it captures something important about this moment. The challenge facing many mid-size operations isn’t about milk prices, feed costs, or management. It’s about debt structures that made perfect sense in one interest rate environment but don’t pencil out in another.

Understanding how this works can help you think through your own situation more clearly, whether you’re facing repricing directly or trying to plan around it.

How Dairy Loan Repricing Works

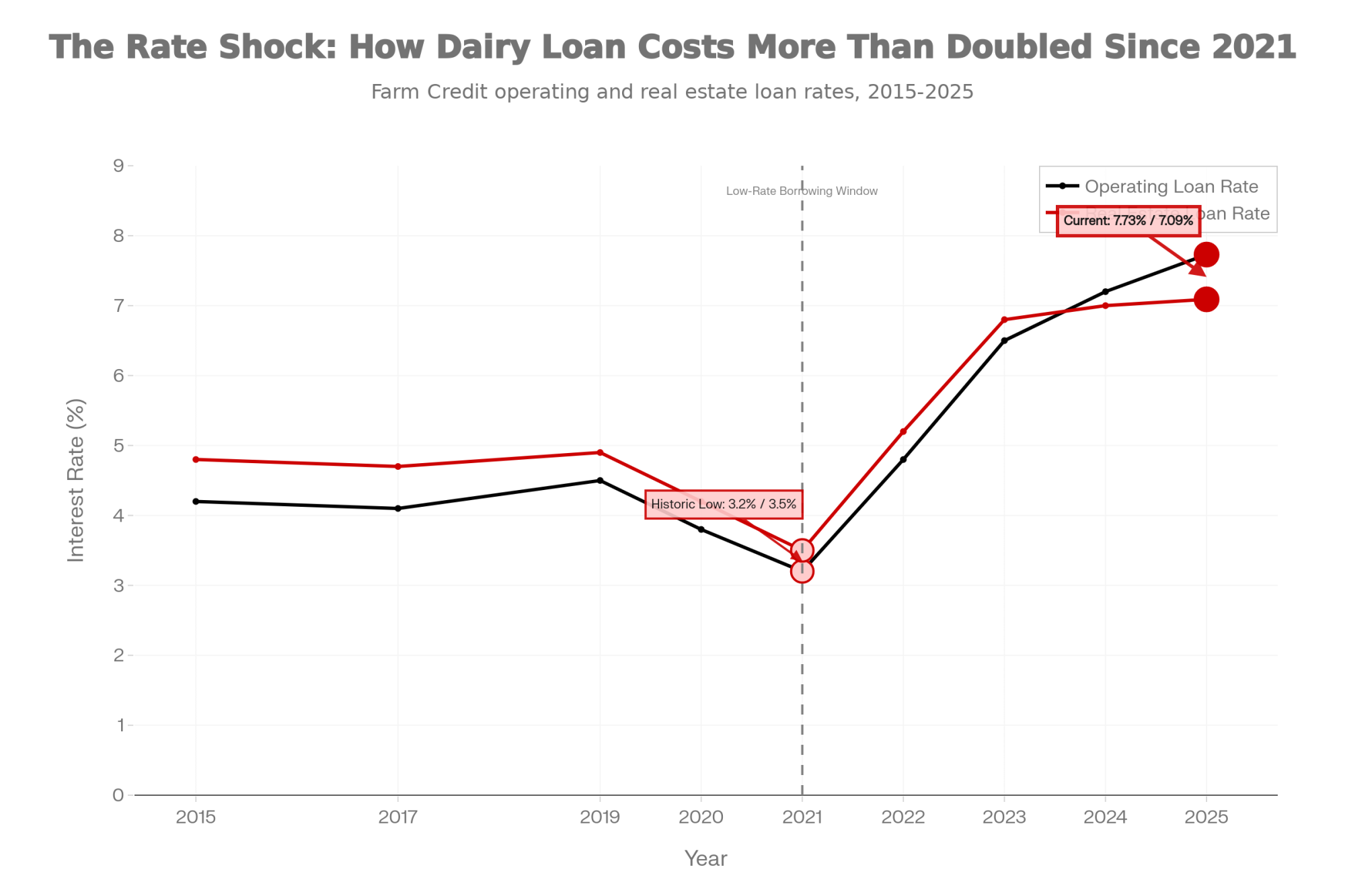

Here’s the backstory. During that stretch from roughly 2015 to 2021, agricultural lenders originated an enormous volume of dairy farm debt at rates between 3% and 4.5%. These loans financed the expansions, land purchases, parlor upgrades, and equipment investments that allowed mid-size operations to modernize and grow. It was, by most measures, a reasonable time to borrow.

Most of these loans were structured with 5-to-7-year terms before repricing—standard practice for agricultural real estate and equipment financing. What that means, practically speaking, is that a significant wave of debt is now resetting to current market rates. Federal Reserve Bank surveys throughout 2025 have documented this transition, with the Minneapolis Fed noting weakening credit conditions and declining farm incomes across the Ninth District.

The rate environment has changed substantially. The Chicago Fed’s agricultural credit survey from early 2025 shows operating loans averaging 7.73% and real estate loans at 7.09%. That’s roughly double what many producers locked in five or six years ago.

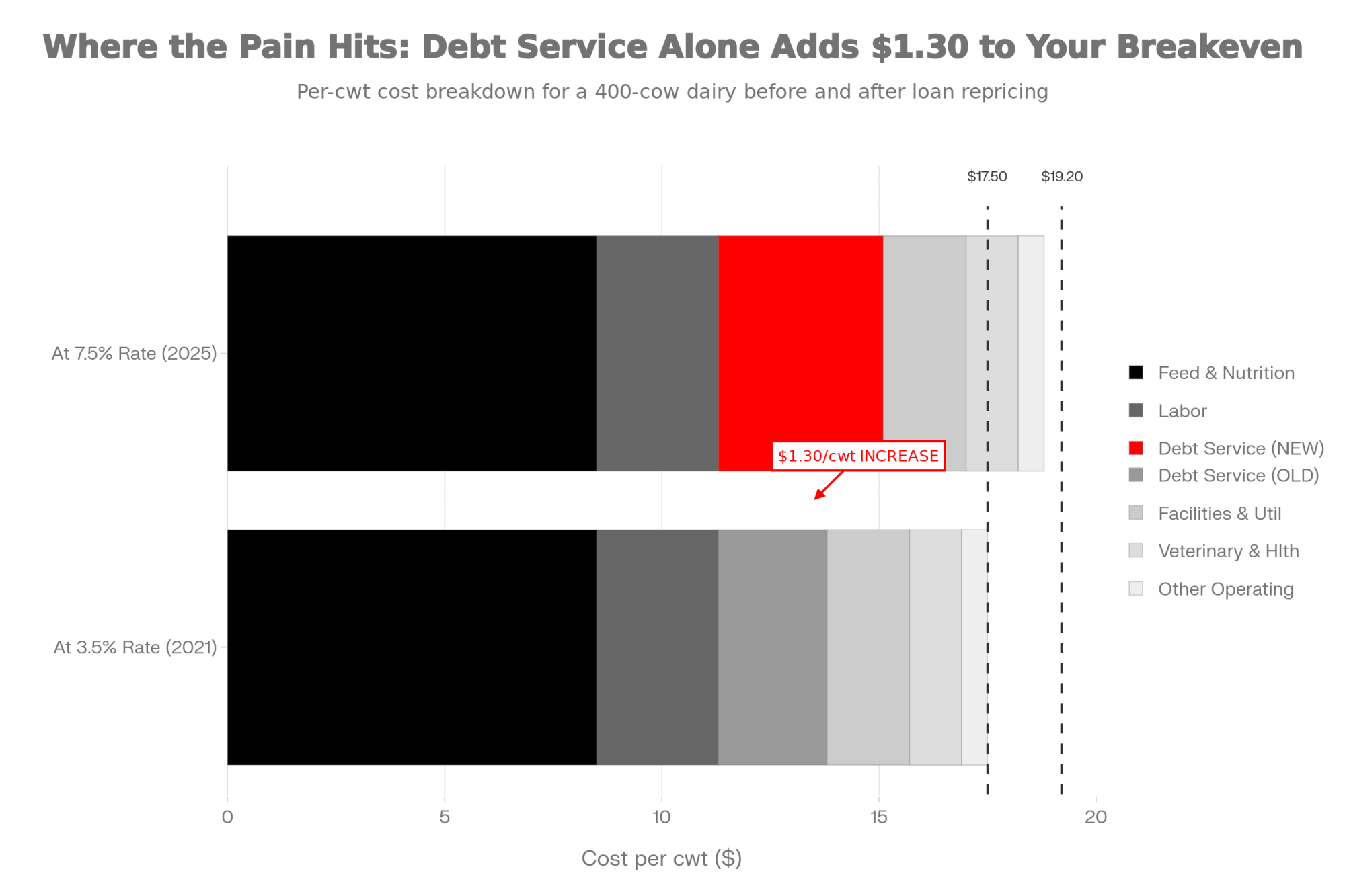

To put some numbers to this, consider a fairly typical 400-cow dairy carrying $4.5 million in total debt—the kind of balance sheet you’d see on a farm that expanded or did major capital improvements during that low-rate window:

The Repricing Impact: A Side-by-Side Comparison

| Debt Category | Original Rates (2020-2021) | Repriced Rates (2025) | Annual Increase |

| Real Estate Debt (15-year) | 3.5% → $232,000/yr | 7.5% → $300,000/yr | +$68,000 |

| Equipment Debt (7-year) | 4.0% → $197,000/yr | 7.0% → $217,000/yr | +$20,000 |

| Operating Line | 3.0% → $18,000/yr | 8.0% → $48,000/yr | +$30,000 |

| TOTAL ANNUAL DEBT SERVICE | $446,000 | $566,000 | +$120,000 (+27%) |

Based on a representative 400-cow dairy with $4.5 million total debt. Actual figures vary by operation.

That $120,000 difference translates to roughly $1.30 per hundredweight across a year’s production. For operations already running on tight margins, that kind of shift can consume the entire profit cushion that existed under the previous rate structure.

Dr. Mark Stephenson, the former Director of Dairy Policy Analysis at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, frames it this way: “What we’re seeing is farms that were profitable, well-managed, and operationally sound suddenly finding themselves underwater. It’s not a management problem. It’s a capital structure problem that originated in decisions made by both borrowers and lenders five to seven years ago.”

That framing matters. This isn’t about who’s a good farmer. It’s about financial structures adapting to changing conditions.

Which Dairy Farms Face the Greatest Repricing Risk

Operations under the greatest pressure tend to share certain characteristics. They’re typically in the 200 to 600 cow range—large enough to carry significant debt, but not quite large enough to achieve the per-unit cost advantages that help buffer larger operations against margin compression. They’re generally carrying debt-to-asset ratios between 65% and 70%, which means they’re leveraged enough that repricing creates covenant pressure, but weren’t in distress before rates moved. And most originated their loans between 2017 and 2021, during that window of historically low rates.

Geographically, the pressure seems most concentrated in traditional dairy regions. I’m hearing the most concern in Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Pennsylvania, and parts of California and Idaho. The dynamics play out somewhat differently in Western dry-lot operations, where scale economics and distinct cost structures create distinct patterns. And in Canadian quota provinces, the supply management system provides some insulation, though producers there face their own version of capital intensity challenges.

The broader context here is important. The 2022 Census of Agriculture documented that approximately 65% of the nation’s dairy herd now lives on operations with 1,000 or more cows—up from just 17% back in 1997. That trajectory has been building for decades, but the current rate environment appears to be accelerating it.

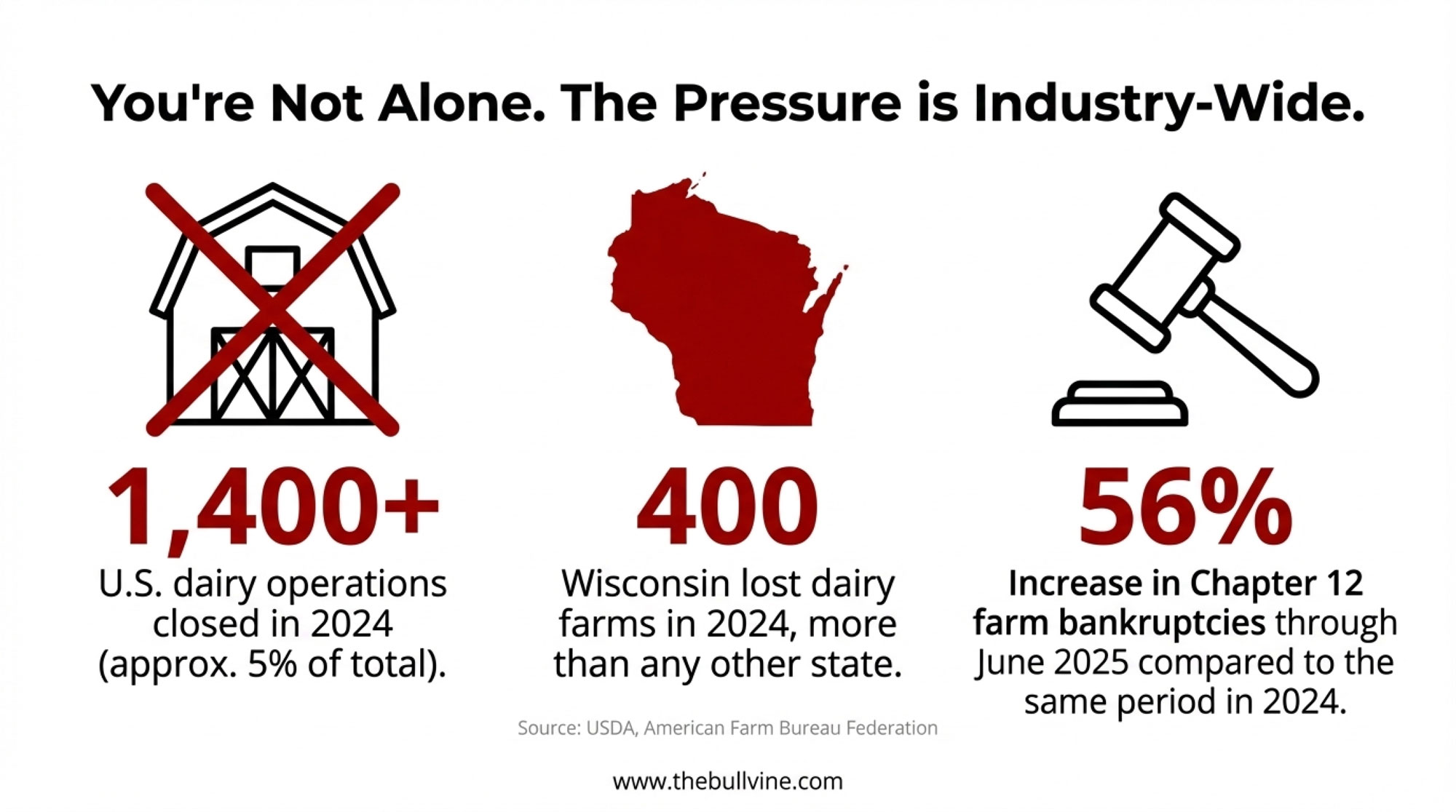

USDA’s February 2025 milk production report showed that more than 1,400 U.S. dairy operations closed in 2024—about 5% of the national total. Wisconsin lost approximately 400 dairy farms that year, more than any other state, followed by Minnesota with 165 closures. Those aren’t just statistics. Each one represents a family working through some very difficult decisions.

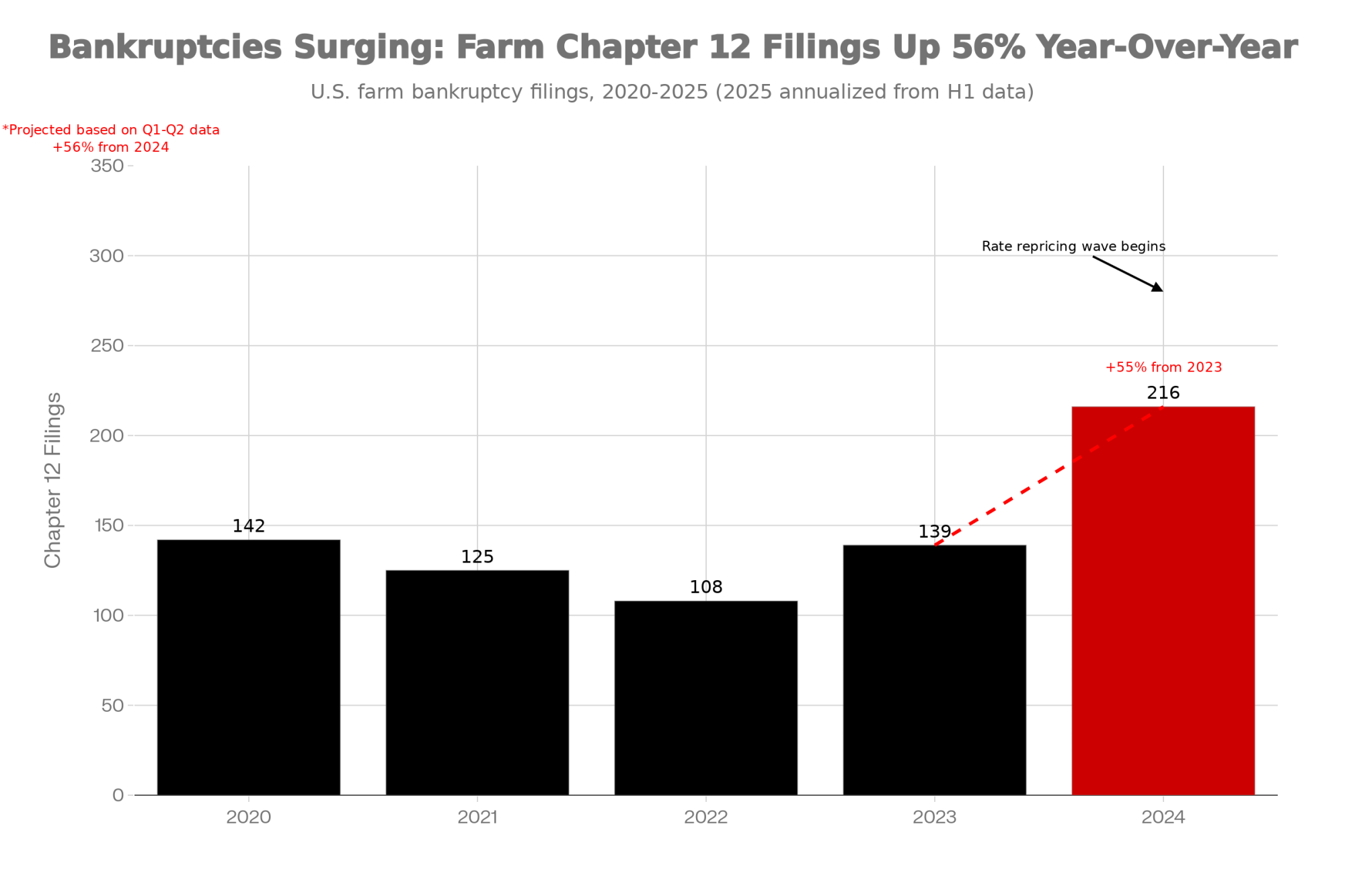

The stress extends beyond dairy. The American Farm Bureau Federation reported that Chapter 12 farm bankruptcies—the filing type designed specifically for family operations—were up 56% through June 2025 compared to the same period in 2024. For all of 2024, there were 216 Chapter 12 filings nationally, up 55% from 2023. The Kansas City Fed noted in their mid-2025 agricultural finance report that farm loan delinquency rates have increased for the second consecutive year, though they remain low by historical standards.

These indicators don’t necessarily predict a crisis, but they do suggest the farm economy is under meaningful pressure that warrants attention.

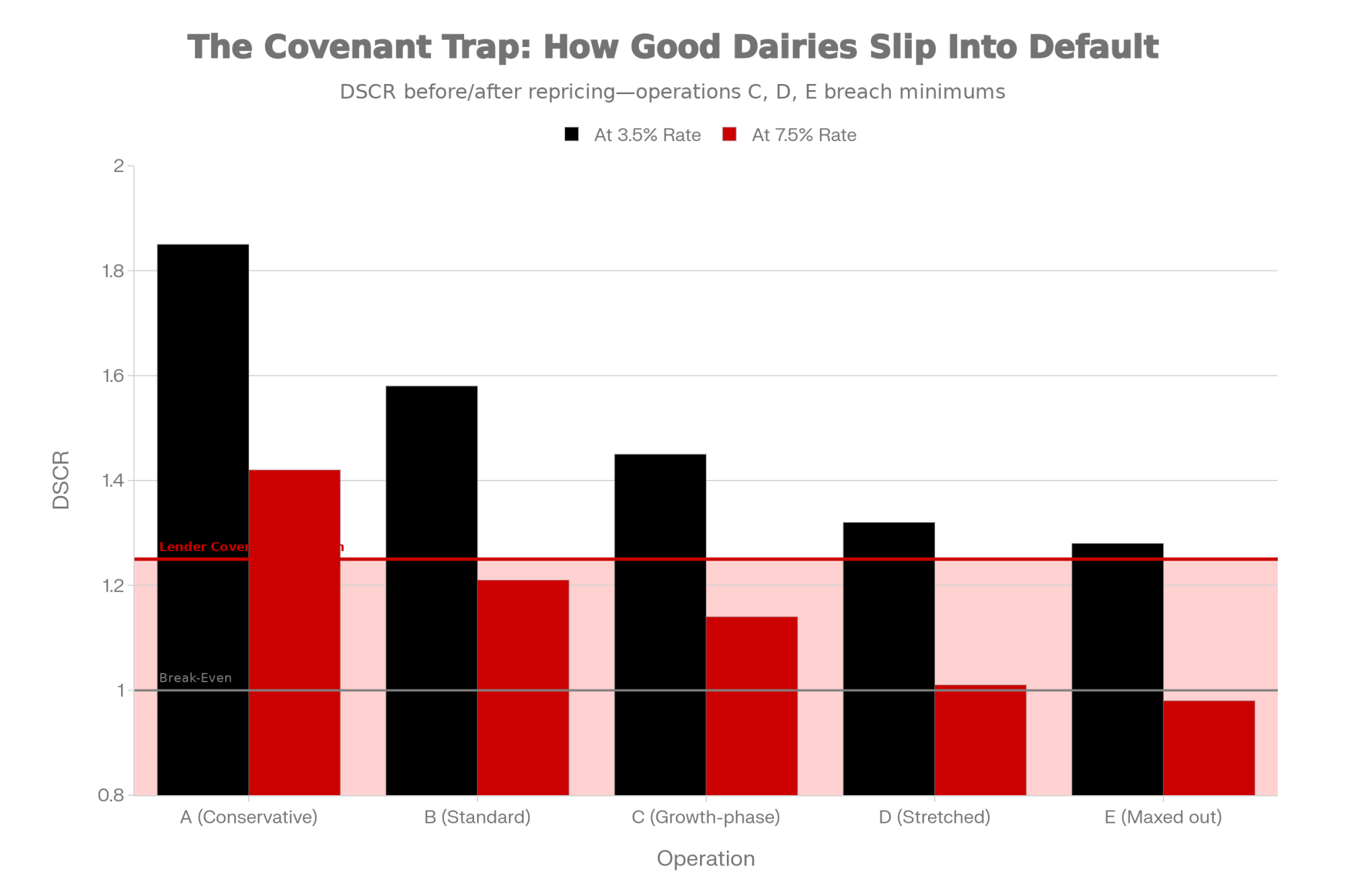

The Loan Covenant Trap Many Producers Miss

This is an area where I think many producers could benefit from a clearer understanding, because it often becomes relevant before anyone expects it.

Most agricultural loans include financial covenants—requirements that borrowers maintain certain ratios to remain in good standing. The common ones include:

- Debt Service Coverage Ratio: Typically 1.25x minimum, meaning net farm income needs to exceed debt payments by at least 25%

- Current Ratio: Often 1.5x minimum, measuring working capital adequacy

- Debt-to-Asset Ratio: Usually capped at around 60%

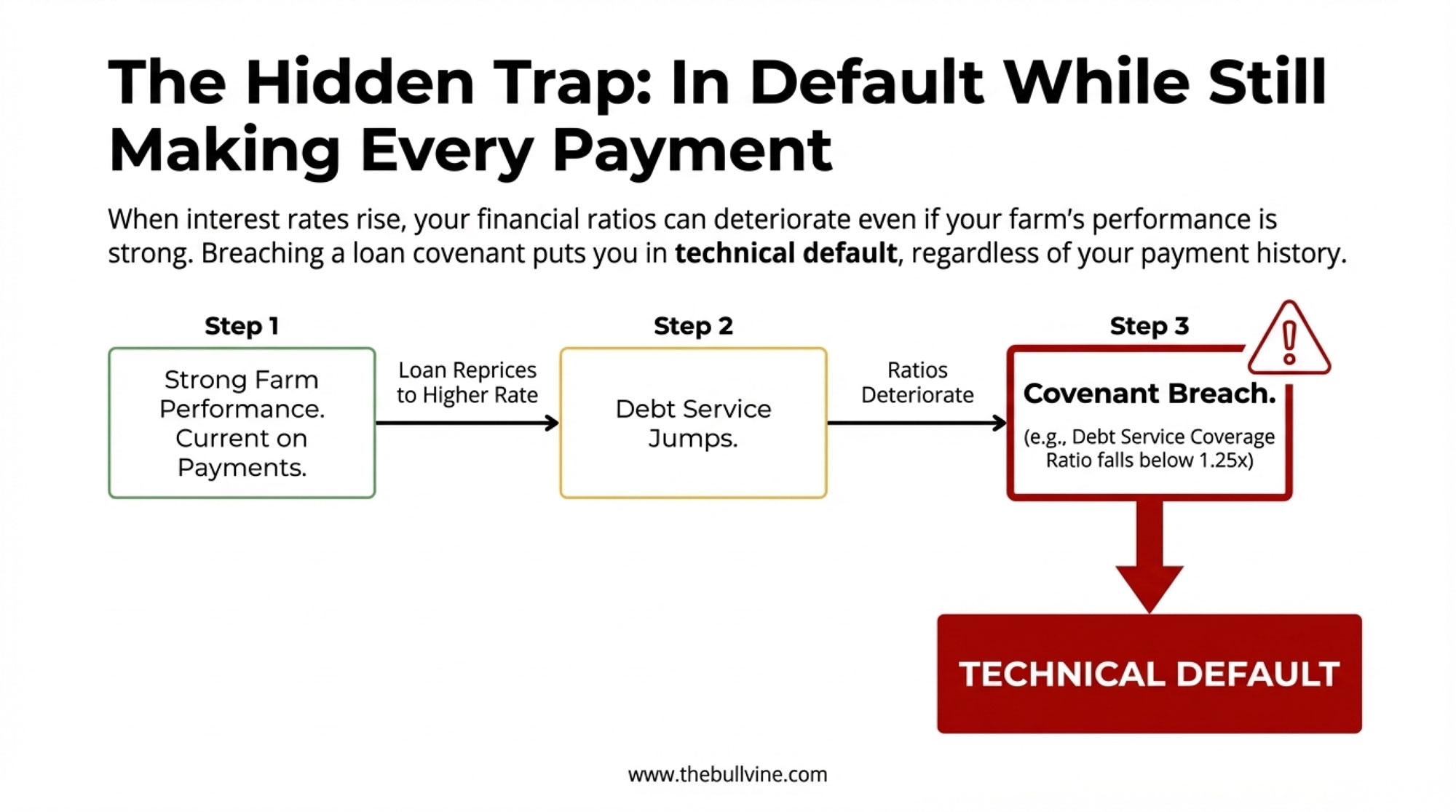

Here’s what’s worth understanding: when interest rates rise and debt service increases, these ratios can deteriorate even when operational performance remains strong. A dairy that comfortably met a 1.45x debt service coverage ratio at old rates might find itself at 1.14x after repricing—technically in covenant breach, even though production, costs, and management quality haven’t changed.

The wrinkle that surprises many producers is that once a covenant is breached, the loan is technically in default regardless of whether payments are current. This can trigger a sequence of lender responses.

I’ve spoken with agricultural lending professionals at several Farm Credit associations across the Midwest about how this plays out. As one loan officer with more than two decades of experience described it: “The farm could be making every payment on time, the cows could be performing beautifully, and they’re still in technical default. Those are hard conversations to have with producers who are doing everything right operationally.”

The typical progression involves enhanced reporting requirements first—monthly financials instead of quarterly. Then restrictions on capital expenditures and owner draws. If covenant compliance doesn’t improve, there may be requests for equity contributions or principal reduction. In more serious cases, loan acceleration becomes possible.

None of this is inevitable, and many lenders work constructively with borrowers to find solutions. But understanding the framework helps in planning how to approach these conversations.

Strategic Options and What They Can Realistically Achieve

I want to be straightforward here. There’s no simple fix for a structural repricing challenge. But some approaches can help, and understanding both their potential and their limitations is valuable.

Comparing Your Options

| Strategy | Potential Annual Savings | Key Limitation |

| Amortization Extension (15→25 yr) | $80,000–$100,000 | Doesn’t reduce principal; extends total interest paid |

| Strategic Herd Reduction (15-25%) | $60,000–$80,000 | Revenue declines proportionally with a smaller herd |

| Operational Efficiency Gains | $55,000–$74,000 | Rarely sufficient alone for $120K repricing gap |

| FSA Refinancing (4.625%–5.75%) | Varies by exposure | $600K ownership / $400K operating caps |

| Private Ag Lenders | Covenant flexibility | Rates are often comparable or higher than repricing levels |

Savings estimates based on a representative 400-cow operation. Individual results vary significantly.

Engaging Your Lender Early

This consistently emerges as the most effective intervention. Producers who engage their lenders before repricing notices arrive—rather than after covenant issues develop—generally report more constructive conversations and better outcomes.

The difference between proactive and reactive discussions is substantial. When a producer approaches their lender with a thought-out plan before being flagged in the system, there’s typically more flexibility to work with. Once an account is classified as a problem asset, institutional constraints tend to narrow the options. That’s not a criticism of lenders—it’s just how credit administration typically works.

Approaches that seem to help include extending amortization from 15 years to 20-25 years (which can reduce annual payments by $80,000 to $100,000), requesting covenant modifications that reflect rate-driven rather than operational changes, and presenting cash flow projections based on realistic milk prices in that $18 to $19 per hundredweight range rather than more optimistic scenarios.

One thing I’d suggest: come to that meeting with a specific proposal rather than a list of possibilities. Demonstrate that you’ve carefully worked through the numbers. And focus on the financial analysis rather than the emotional weight of the situation—lenders work from models, and you’ll communicate more effectively if you engage on those terms.

Considering Herd Adjustments

Some operations are finding that a deliberate reduction in herd size—typically 15% to 25%—can restore financial stability when combined with proportional debt reduction.

The arithmetic: selling 80 cows from a 400-cow operation might generate $600,000 to $800,000 in proceeds, depending on cow values and quota where applicable. Applied directly to debt reduction, this can decrease annual debt service by $60,000 to $80,000—a meaningful offset against repricing impact.

The trade-off is real, though. Revenue declines with a smaller herd. This approach works better as a bridge to stability than as a permanent solution. A 320-cow operation carrying $3.8 million in debt at current rates still faces challenging economics. You’re creating breathing room, not resolving the underlying situation.

Operational Improvements

Focused attention on cost reduction absolutely has value, but it’s important to be realistic about what’s achievable:

- Nutrition optimization: Working with a skilled nutritionist to refine rations typically yields savings of $0.30 to $0.50 per cwt. On a 92,000 cwt annual production, that’s $27,600 to $46,000—meaningful, but not transformative against a $120,000 repricing impact.

- Labor efficiency: Workflow improvements without major capital investment might capture $0.15 to $0.25 per cwt.

- Component and quality premiums: Optimizing butterfat and protein capture can add $0.20 to $0.30 per cwt if there’s room for improvement. Many operations have already pushed hard on this.

Combined realistic potential runs $0.60 to $0.80 per cwt—roughly $55,000 to $74,000 annually. That’s valuable and worth pursuing regardless of the rate environment. But it’s typically not sufficient on its own to offset a $1.30 per cwt repricing impact.

Alternative Financing Sources

Some producers are exploring options beyond traditional bank and Farm Credit financing:

USDA Farm Service Agency loans currently offer competitive rates—4.625% for direct operating loans and 5.750% for direct farm ownership loans as of December 2025. The constraint is dollar limits: FSA caps direct farm ownership loans at $600,000 and direct operating loans at $400,000. For a farm needing to refinance $2.7 million in real estate debt, these programs can help with a portion, but won’t address the full exposure.

Private agricultural lenders like AgAmerica and Rabo AgriFinance may offer more flexibility on covenant structures. Rates tend to be comparable to or somewhat higher than traditional sources, so this is more about terms than cost savings.

Realistic combined capital access from these alternative sources typically runs $300,000 to $600,000—helpful for bridging gaps, but generally not sufficient to resolve a seven-figure repricing exposure.

A Framework for Making These Decisions

What I’ve found most valuable in conversations with producers facing these decisions is an honest, numbers-first assessment. The emotional weight of these situations is real—often we’re talking about multi-generational operations and family identity. But the financial analysis needs to proceed on its own terms.

This is where working with good advisors makes a difference. Farm transition specialists, agricultural attorneys, and CPAs who understand dairy operations can help families see the full picture and evaluate options they might not have considered.

Some questions worth working through carefully:

- What’s your true breakeven at new rates? This means debt service, operating costs, family living, and a realistic allowance for capital replacement. Calculate it precisely rather than estimating.

- How does that breakeven compare to realistic price expectations? If you’re pushing above $19 per hundredweight, there’s very little margin for the unexpected.

- Do you have access to meaningful outside capital? This could be family resources, off-farm assets, or other sources—but it needs to be real and accessible, not theoretical.

- What signals is your lender sending? There’s often a gap between what we hope they mean and what they actually communicate. Try to hear the latter clearly.

- What does the next generation want? If successors aren’t committed to the operation, the calculus changes significantly.

For operations where the breakeven is pushing toward $20 per cwt, debt-to-asset exceeds 70%, and there’s no access to outside capital, the outlook is genuinely difficult regardless of how well the cows are managed. In those situations, a planned transition—executed while meaningful equity remains—typically preserves substantially more family wealth than a forced exit 18 to 24 months later. Farm transition specialists consistently find that strategic exits preserve considerably more equity than distressed sales—often amounting to several hundred thousand dollars for families with significant remaining assets.

That kind of decision isn’t giving up. It’s sound financial management applied to a difficult situation.

The Other Side of This Story

It’s worth acknowledging that this environment doesn’t affect everyone the same way. Producers who maintained conservative balance sheets through the low-rate years—those who resisted the temptation to expand aggressively or who paid down debt rather than refinancing—find themselves in a very different position today.

For well-capitalized operations with strong working capital and minimal leverage, the current environment may actually present opportunities. Land that wouldn’t have come to market is becoming available. Equipment can be acquired at more favorable prices. Some producers are finding strategic growth opportunities they couldn’t access two years ago.

That’s not meant to minimize what leveraged operations are facing. But it’s a reminder that market stress always creates a range of outcomes. Where you land depends heavily on decisions made years ago—and on the decisions you make now.

What This Means for the Industry

Beyond individual farm decisions, the repricing wave is accelerating structural changes that have been building for some time.

The consolidation trend toward larger operations will likely continue. We’ve already seen the share of cows on 1,000-plus operations climb from 17% in 1997 to 65% in 2022, according to the Census of Agriculture. The mid-size family dairy is becoming an increasingly uncommon business model, particularly in regions without quota systems or other structural supports.

From the processor perspective, the picture is mixed. One Midwest cooperative executive described it this way: consolidation creates certain efficiencies in milk collection and quality consistency. “But we’re also watching our supplier base shrink faster than anyone planned for. When you lose 400 farms in a region over a few years, that’s infrastructure—roads, services, veterinary capacity—that doesn’t rebuild easily.”

Industry organizations are responding. The National Milk Producers Federation has advocated for expanded FSA lending authority, and the PACE Act was reintroduced in Congress in March 2025. If enacted, it would increase the caps on direct farm ownership loans from $600,000 to $1.5 million and on direct operating loans from $400,000 to $800,000. Whether any of this moves quickly enough to help farms facing near-term repricing remains uncertain.

There’s a broader consideration worth noting. As mid-size operations exit, the industry loses independent decision-makers who have historically contributed resilience through diversity of approach. Dr. Marin Bozic, an agricultural economist who spent a decade studying dairy markets at the University of Minnesota, has described this as “trading resilience for efficiency.” That trade-off works well under normal conditions. It becomes a vulnerability when circumstances deviate from what the models anticipated.

Practical Next Steps

For producers facing repricing in the next 12 months:

- Know your numbers precisely. Calculate your exact breakeven cost at new rates—not an estimate, an actual calculation. That number anchors everything else.

- Engage your lender before they engage you. Come with a specific proposal and realistic projections. The conversation is different when you initiate it.

- Build your advisory team now. Connect with a farm transition specialist, an agricultural CPA, and potentially an ag attorney, even if you’re planning to continue. Understanding your options strengthens your position.

For those considering expansion or major capital investment:

- Model everything at current rates. The 3% environment from 2019 isn’t returning in any relevant timeframe. Plan accordingly.

- Stress-test at challenging milk prices. See how your projections hold at $17 to $18 per cwt, not just at more optimistic levels.

- Understand that comfortable leverage at 4% becomes uncomfortable at 7-8%. The production side of your operation doesn’t change, but the financial dynamics shift considerably.

The Bottom Line

What’s unfolding now isn’t primarily about who’s skilled at producing milk. Many capable operations are exiting not because they can’t compete on the production floor, but because debt structures that worked in one rate environment don’t pencil out in another.

We’re going to see more good dairy families work through difficult transitions over the next couple of years. Not because they couldn’t manage cows or run tight operations, but because the financial landscape shifted in ways that were partly foreseeable and partly not.

But here’s something worth remembering: dairy has always adapted. The industry that emerges from this period will look different, yes. Some of the changes will feel like losses. But there will also be opportunities—for those who navigate successfully, for new models that emerge, for the next generation that finds ways to make the economics work.

The families who approach this period with clear financial thinking, good advice, and honest assessment of their situations will be best positioned—whether that means restructuring successfully, transitioning on their own terms, or finding paths forward that none of us have fully anticipated yet.

Understanding the dynamics at play is the first step. What you do with that understanding is up to you.

Key Takeaways

- The cows haven’t changed—the math has: Loans repricing from 3.5% to 7.5% add ~$120,000 annually to a typical mid-size operation, or $1.30/cwt onto breakeven

- You can be current and still default: Covenant breaches trigger technical default even when payments are on time—it’s the ratios, not missed payments, that trip the wire

- Efficiency alone won’t close this gap: Operational improvements typically yield $0.60-$0.80/cwt; helpful, but not sufficient against a $1.30/cwt repricing hit

- Talk to your lender before they talk to you: Proactive conversations with specific restructuring proposals consistently produce better outcomes than reactive ones

- Planned exits beat forced ones: Strategic transitions preserve significantly more family equity than fighting until liquidation becomes the only option

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- The Next 18 Months Will Decide Who’s Still Milking in 2030 – Here’s Your Checklist – Provides a critical survival checklist for producers facing the repricing window, detailing specific financial benchmarks and timelines you must hit to remain viable through the current consolidation cycle.

- Decide or Decline: 2025 and the Future of Mid-Size Dairies – Examines the specific “middle-ground” squeeze affecting 200-600 cow herds and outlines three distinct business models that are successfully navigating the gap between small-scale premiums and large-scale efficiency.

- The 90-Second Milking Window That’s Paying $126,000 – and Beating Every Robot – Reveals how optimizing milk letdown protocols can generate six-figure returns without new loans, offering a capital-free alternative to expensive robotic installations for cash-conscious operations.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.