If your “fair” buyout loads $600+ of debt on every cow, you’re not doing succession—you’re planning a dispersal in slow motion.

You know how some topics just keep coming up over coffee at farm meetings? Succession is one of those.

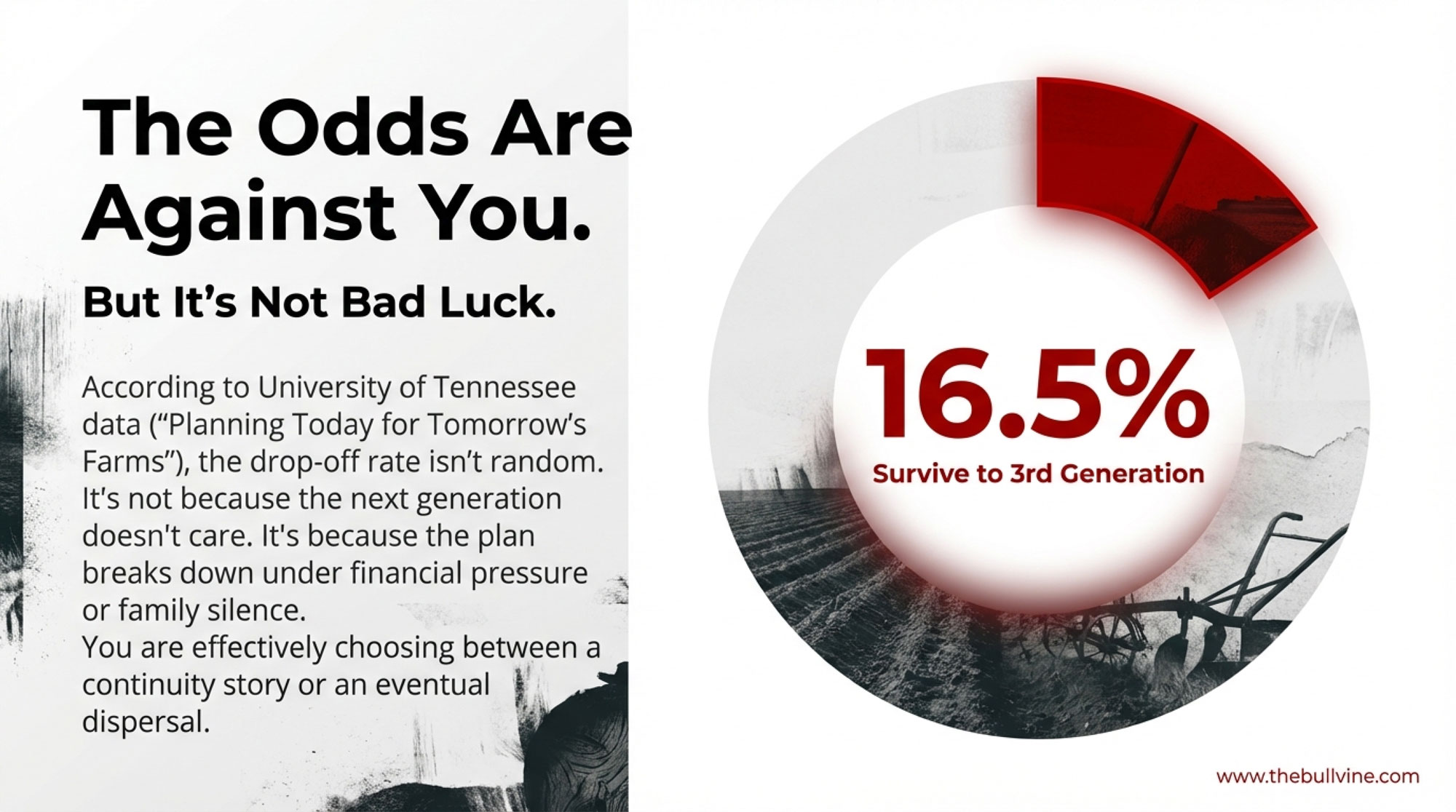

Let’s walk through what the numbers and the real‑world experience are telling us about keeping dairy farms in the family—and how the roughly 16.5% who pull it off tend to do things differently.

The Odds Aren’t Great—but They’re Not Hopeless

Most family business owners have heard some version of the “three‑generation rule.” A lot of talks and articles still repeat the old line that about 30% of family businesses make it to the second generation, around 10–15% to the third, and only 3–5% to the fourth. You’ve probably heard that at a seminar at some point.

A critical look in Family Business Magazine noted that those specific percentages aren’t a universal law, but they’re a decent rule of thumb: many family firms fall away at each transition, and only a minority make it to the third or fourth hand‑off. The Family Business Consulting Group goes a step further and says you should think of it as “about one‑third survive each generational transition,” not a guaranteed 30/13/3 every time.

The University of Tennessee took that one‑third idea and did the farm math. Their Planning Today for Tomorrow’s Farms workbook walks through the logic: if roughly a third of family businesses survive the first transition, and about a third of those survive the second, then you’re looking at something like 16.5% of family farms reaching a third generation of ownership. And they’re very clear that weak or non‑existent succession planning is one of the big reasons many don’t get that far.

| Generation Milestone | Percentage Surviving |

|---|---|

| 1st Gen to 2nd Gen | ~100% (baseline) |

| 2nd Gen to 3rd Gen | ~33% (of 2nd) |

| 3rd Gen to 4th Gen | ~11% (of 3rd) |

| Farms Reaching 4th+ Gen | ~3.5% (of original) |

So, yes, the odds are tough. But they’re not a death sentence. What I’ve found, looking at the research and listening to farmers in places like Wisconsin, Ontario, and the Atlantic provinces, is that the families who do land in that 16‑odd percent tend to make a set of very specific choices—on timing, money, fairness, and leadership.

Let’s talk about those, in plain dairy terms.

Why Dairy Succession Feels Heavier Than Most

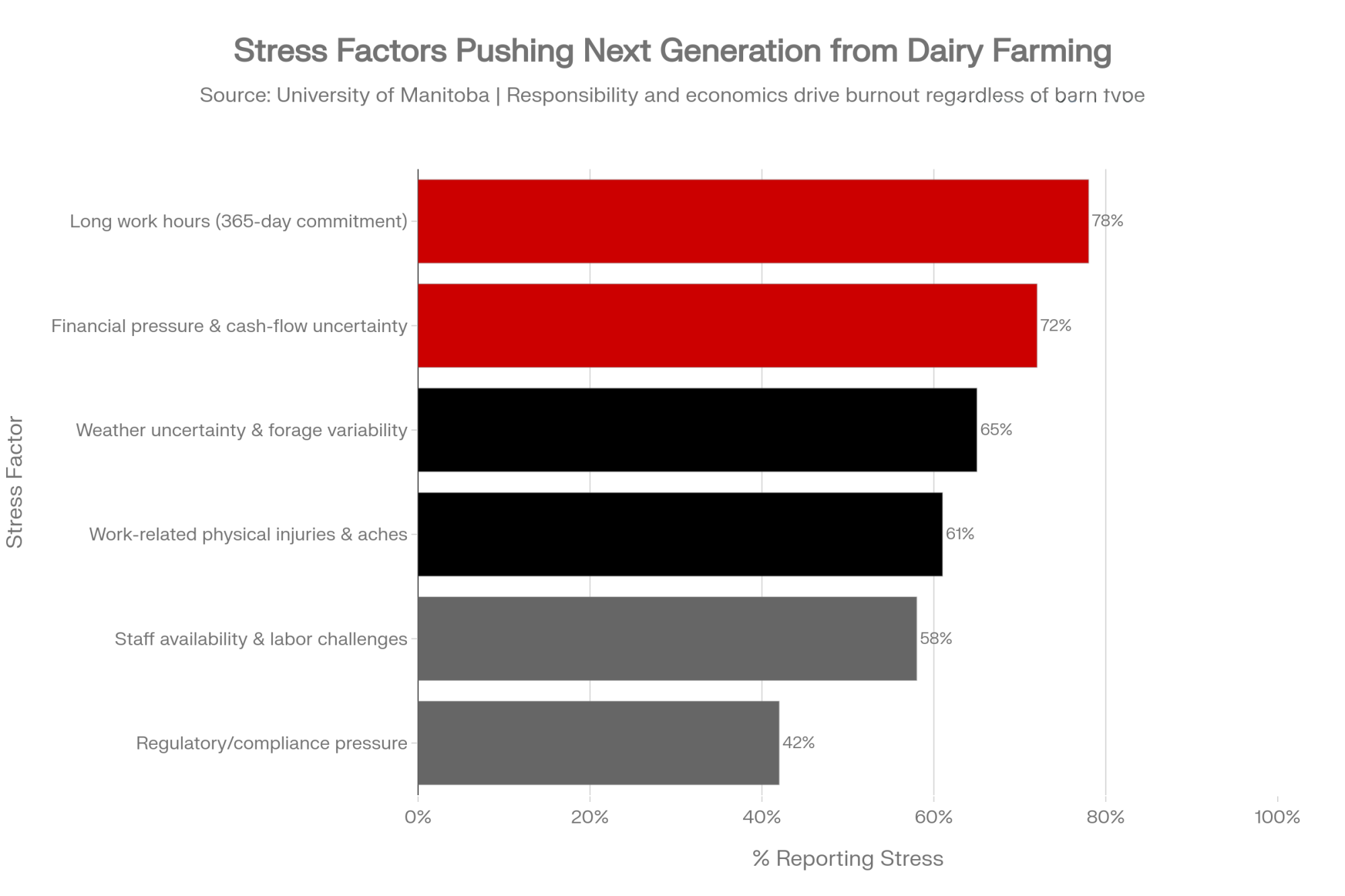

You don’t need a journal article to tell you dairy is a 365‑day grind, but it’s worth seeing how the data lines up with what you’re living.

The 365‑Day Workload Your Kids Have Watched

A 2024 doctoral thesis from the University of Manitoba interviewed dairy farmers in Western Canada and Ontario about health and workload. It found what most of us already know in our bones: a lot of producers reported work‑related injuries, aches, and pretty high stress levels. The main culprits were long hours, heavy workloads, financial pressure, and weather uncertainty.

What’s interesting is that the study didn’t see big differences in health outcomes between tie‑stall and freestall, or between parlors and robots—once you controlled for other factors, the stress seemed to come from the responsibility and economics as much as from the barn layout.

If your kids grew up watching you drag yourself in after dealing with fresh cow issues in the transition period, juggling butterfat levels for that component premium, and worrying about the line of numbers on the cash‑flow sheet, they absorbed all of that. In more than a few kitchen‑table meetings, I’ve heard young people say something along the lines of, “I love the cows and the genetics. I’m just not sure I want to live exactly like my parents did.”

That doesn’t mean they won’t come back. But it does mean we can’t pretend the lifestyle piece isn’t part of the succession puzzle.

| Stress Factor | % of Farmers Reporting High Levels | Relative Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Long work hours (365-day commitment) | 78% | High |

| Financial pressure & cash-flow uncertainty | 72% | High |

| Weather uncertainty & forage variability | 65% | Medium-High |

| Work-related physical injuries & aches | 61% | Medium-High |

| Staff availability & labor challenges | 58% | Medium |

| Regulatory/compliance pressure | 42% | Medium |

The Capital Load Has Quietly Gotten Bigger

On the balance‑sheet side, dairy has become a very capital‑intensive business. A 2021 paper in the journal Agricultureexamined family farms in Catalonia and found that dairy farms in that region carry particularly high levels of fixed capital in land and buildings compared to other sectors. That’s not news to anyone who’s priced out a new freestall, manure system, or robotic milking setup lately.

In many North American dairy areas, USDA land value surveys and provincial numbers show land values have trended upward over the last decade, especially where urban growth or high‑value crops compete with dairy for acres. Add in barns, parlors or robot rooms, manure storage, feed storage, and in Canada, quota on top of it—and it’s easy to see how a “modest” family dairy can end up with several million dollars tied up in fixed assets.

It’s worth noting what’s happened on the return side. The 2024 Minnesota FINBIN report showed that dairy farms had a much better year than 2023: median net farm income for dairies was up sharply, and milk price and production per cow both improved. High‑profit dairy farms in that dataset earned about 773 dollars per cow in net return. At the same time, the average Minnesota farm across all sectors posted about a 2% rate of return on assets in 2024.

So you’ve got more capital tied up, a better 2024 than 2023, but still a business that, on average, is spinning out something like a 2% return on the total asset base. Many Midwest producers will tell you they feel that in their gut: it’s good enough to keep going and reinvest a bit, but there isn’t a lot of slack for big mistakes.

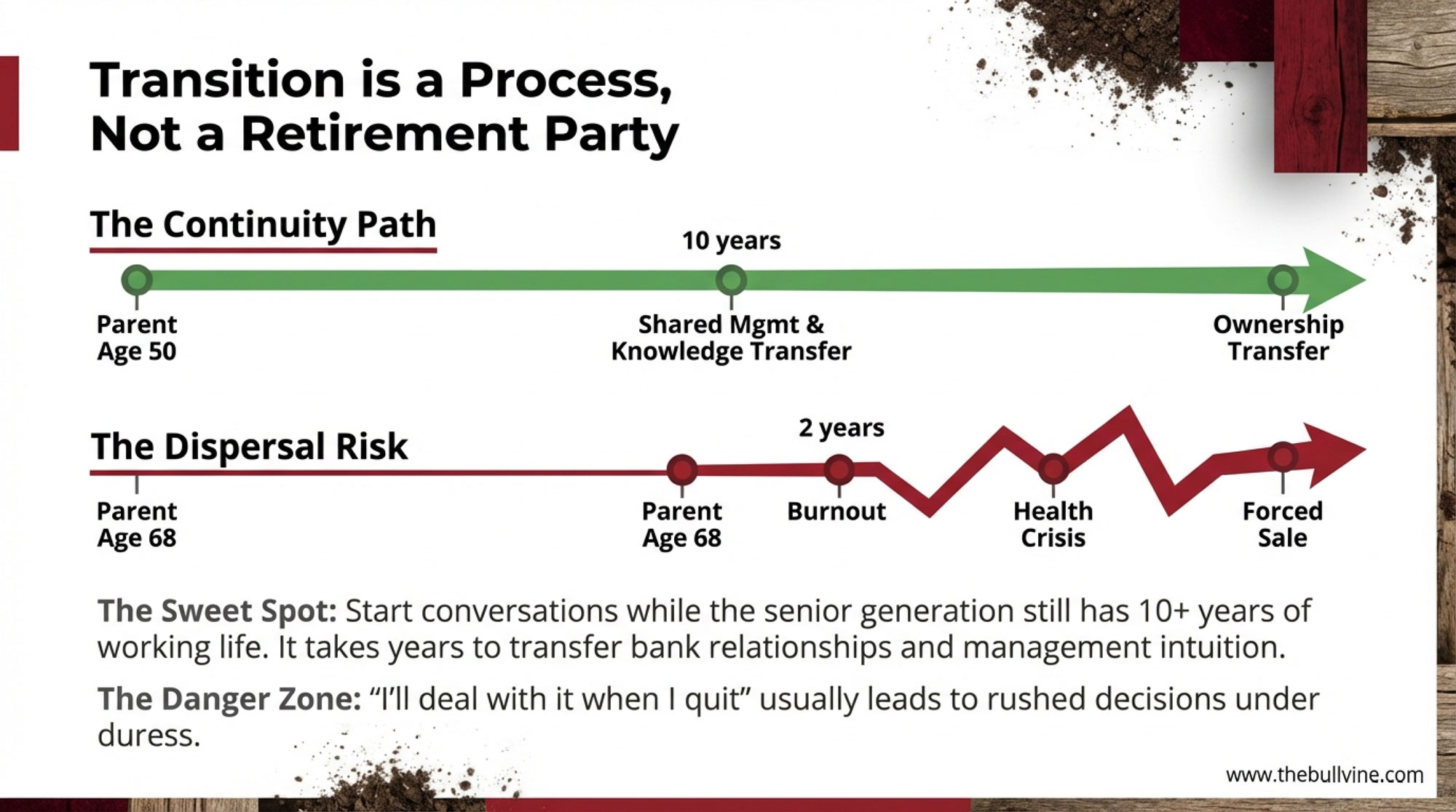

Decision #1: Start the Transition While You Still Have Time, Not When You’re Exhausted

One of the most encouraging things I’ve seen in the last few years is how much more open producers are to talking about timing. Instead of waiting until someone is 68 and worn out, more families are at least asking, “When should we start this?”

Extension folks in a lot of places are saying roughly the same thing. Guides from Michigan State University, OMAFRA in Ontario, and Alberta Agriculture all stress that transition is a multi‑year process and that it works best when you start while the senior generation still has a decade or more of working life ahead of them—often when parents are in their 50s, and a potential successor is in their 20s or 30s. Tennessee’s workbook makes the same point: succession is a process, not a single event.

You probably know this already, but it’s worth saying out loud: “We’ll deal with that when I’m ready to quit” almost never leads to a calm, orderly hand‑off. What it usually leads to is rushed decisions under pressure—health issues, burnout, or a financial shock—and far fewer tools on the table.

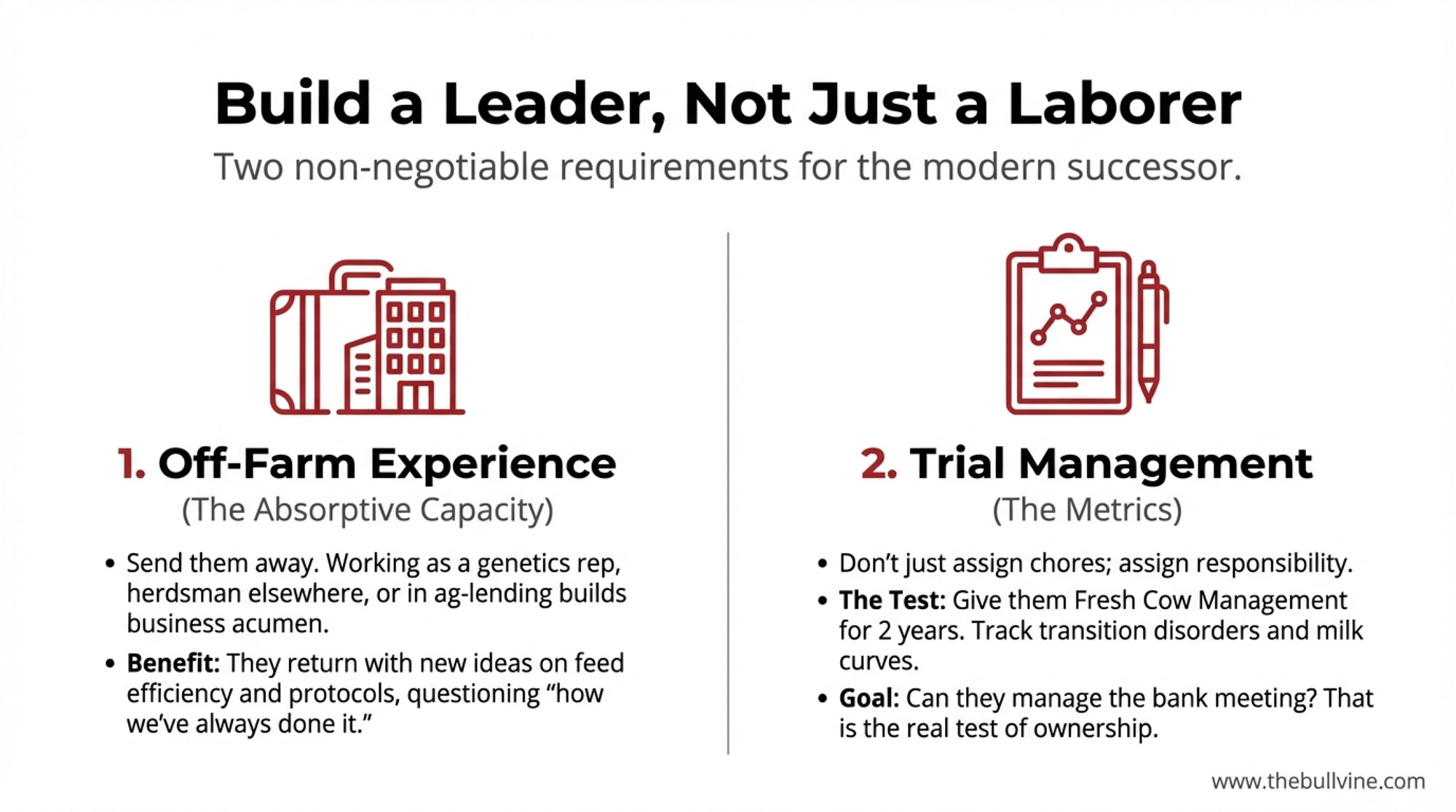

Off‑Farm Experience Isn’t the Enemy

There was a time when a lot of us were terrified that if the kids left, they’d never come back. And sure, that still happens sometimes. But the research and real‑world examples suggest the picture is more nuanced.

A 2018 article in Rural Sociology followed young farmers in England and looked at how education and off‑farm work shaped their paths back to the farm. The authors found that time away often gave these successors a broader perspective and a more entrepreneurial mindset. They came back with different ideas about management, markets, and where the farm could go.

On the ground, in Wisconsin operations and across Western Canada, you see it play out like this:

- Someone spends a few years as a herdsman or assistant manager on a 1,000‑cow freestall or large dry‑lot, really owning fresh cow management and transition‑period decisions.

- Another works as a nutrition or genetics rep, seeing how different herds manage feed costs per cwt, butterfat and protein, SCC, repro, and genomic selection.

- Others spend time in lending, farm management consulting, or robotics, and start thinking more about ROI on capital, not just getting through chores.

When those people come back, what I’ve found is that they usually appreciate how hard the home farm has worked to stay afloat, but they’re also more comfortable questioning things that don’t pencil out. That’s exactly the kind of “absorptive capacity” the Brazilian succession study talked about—being able to bring in outside knowledge and actually use it on the farm.

Instead of seeing off‑farm work as “losing” a successor, you can look at it as sending them out for free training in someone else’s barn.

| Competency Area | With Off-Farm Experience | Home-Farm-Only Experience |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh-cow / transition management | 8.2 | 5.8 |

| Financial / ROI thinking | 7.9 | 4.1 |

| Feed economics & forage management | 8.1 | 5.2 |

| Staff leadership & HR | 7.6 | 4.3 |

| Technology adoption & problem-solving | 8.4 | 5.5 |

| Ability to question & improve existing systems | 8.3 | 4.9 |

Trial Management Back Home: Give Them the Keys, Watch the Numbers

Once they’re back home, the real test isn’t how many hours they work. It’s whether they can actually manage. Extension material from Missouri, Wisconsin, and groups like Land For Good all encourage farms to have a genuine trial‑management period before full partnership.

That might look like:

- Turning fresh cow management over to them for two full years—rations, protocols, pen moves—and then sitting down together to look at transition disorders, early cull rates, and milk curves.

- Letting them design and run the cropping plan, then tracking forage quality, yield, cost per ton of dry matter, and how that feeds into milk production and component levels.

- Giving them responsibility for staff scheduling and day‑to‑day HR, then watching labor turnover, how often you’re short‑staffed, and how the culture feels.

In Minnesota FINBIN herds and in lender meetings I’ve sat in on, those kinds of documented responsibilities and results make it much easier for a bank to say, “Yes, we can finance a staged buy‑in here.” You’re not just asking them to trust a last name—you’re showing them a track record.

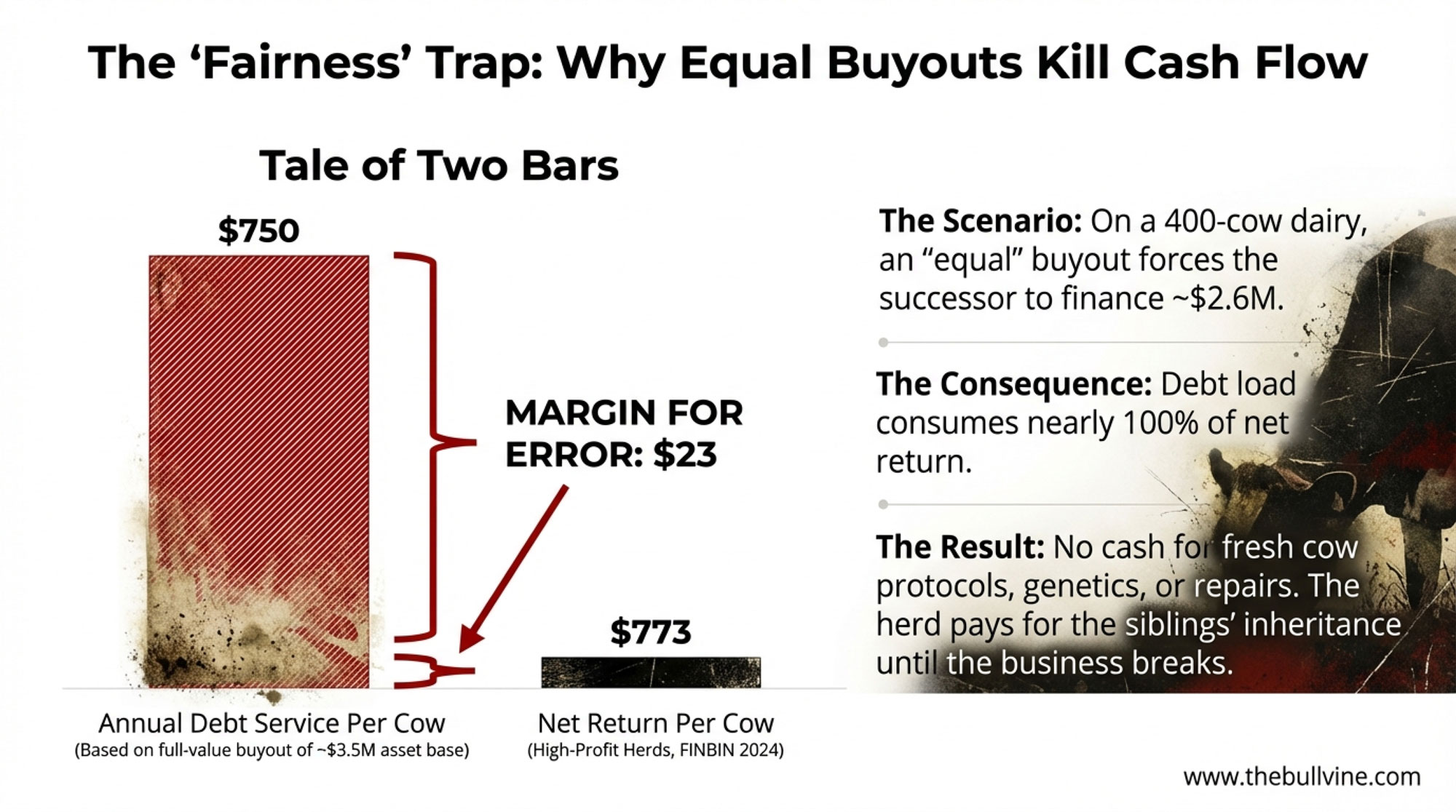

Decision #2: Treat the Old “Equal at Full Value” Plan as a Red Flag, Not a Default

Here’s where the math and the emotions collide. A lot of us grew up with the idea that the “fair” plan was to figure out what the farm was worth, divide by the number of kids, and have the one who stays buy out the rest at that value. On paper, that sounds tidy. On a modern dairy balance sheet, it can quietly set the farm up for failure.

Let’s walk through an example—strictly as an example, not as a “this is what every 400‑cow herd looks like.”

An Illustrative 400‑Cow Scenario

Say you’ve got a 400‑cow herd with assets that look a lot like what FINBIN sees in Minnesota dairies:

- Roughly 2 million dollars in land and buildings

- Around 800,000 dollars in cows and replacements

- Maybe 700,000 dollars in machinery and other assets

That’s about 3.5 million dollars in total assets. If you’ve got four kids and decide everybody’s share should be equal in dollar terms, each person’s “piece” is about 875,000 dollars. If only one child is farming, the on‑farm heir is on the hook to come up with something like 2.6 million dollars to buy out the other three.

Now bring in the income side. FINBIN’s 2024 report showed high‑profit Minnesota dairy farms earning about 773 dollars per cow in net return. Let’s say your 400‑cow herd is in that neighborhood. That’s just over 300,000 dollars in net return available.

If you finance a 2.6‑million‑dollar buyout on typical terms, annual payments can easily land somewhere in the 250,000 to 300,000‑dollar range, depending on the interest rate and amortization. On a 400‑cow base, that works out to roughly 625 to 750 dollars per cow per year just to service buyout debt.

| Item | Amount | Per-Cow Impact | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Farm Assets | $3,500,000 | — | Land ($2M) + Cows/Replacements ($800K) + Machinery ($700K) |

| Equal Share per 4 Kids | $875,000 | — | Farm divided equally; 1 child farming, 3 non-farming |

| Buyout Debt (Successor’s Share) | $2,600,000 | $6,500/cow | Successor buys out 3 siblings’ equity |

| Annual Debt Service | $250–$300K | $625–$750/cow | Typical amortization at 5–6.5% over 15–20 years |

| Net Farm Income (400-cow herd) | $309,200 | $773/cow | Based on FINBIN 2024 high-profit dairy farms |

| % of Income Consumed by Debt | 81–97% | $625–$750 of $773 | Leaves little room for reinvestment, feed spikes, or technology |

Here’s what’s interesting: the same FINBIN report tells us the average Minnesota farm only earned about a 2% rate of return on assets in 2024. So you’re asking a business with a 2% return profile to finance a 100% buyout of all that equity and still have enough left over to invest in cows, barns, manure systems, maybe a robot or two, not to mention handle feed spikes and milk‑price dips.

In a lot of cases, that math just doesn’t leave room for fresh cow improvements, better transition‑period facilities, or upgrading genetics and technology. Many of us have seen what happens next: land and cows get sold off piece by piece to relieve the pressure, and the farm slowly shrinks or disappears.

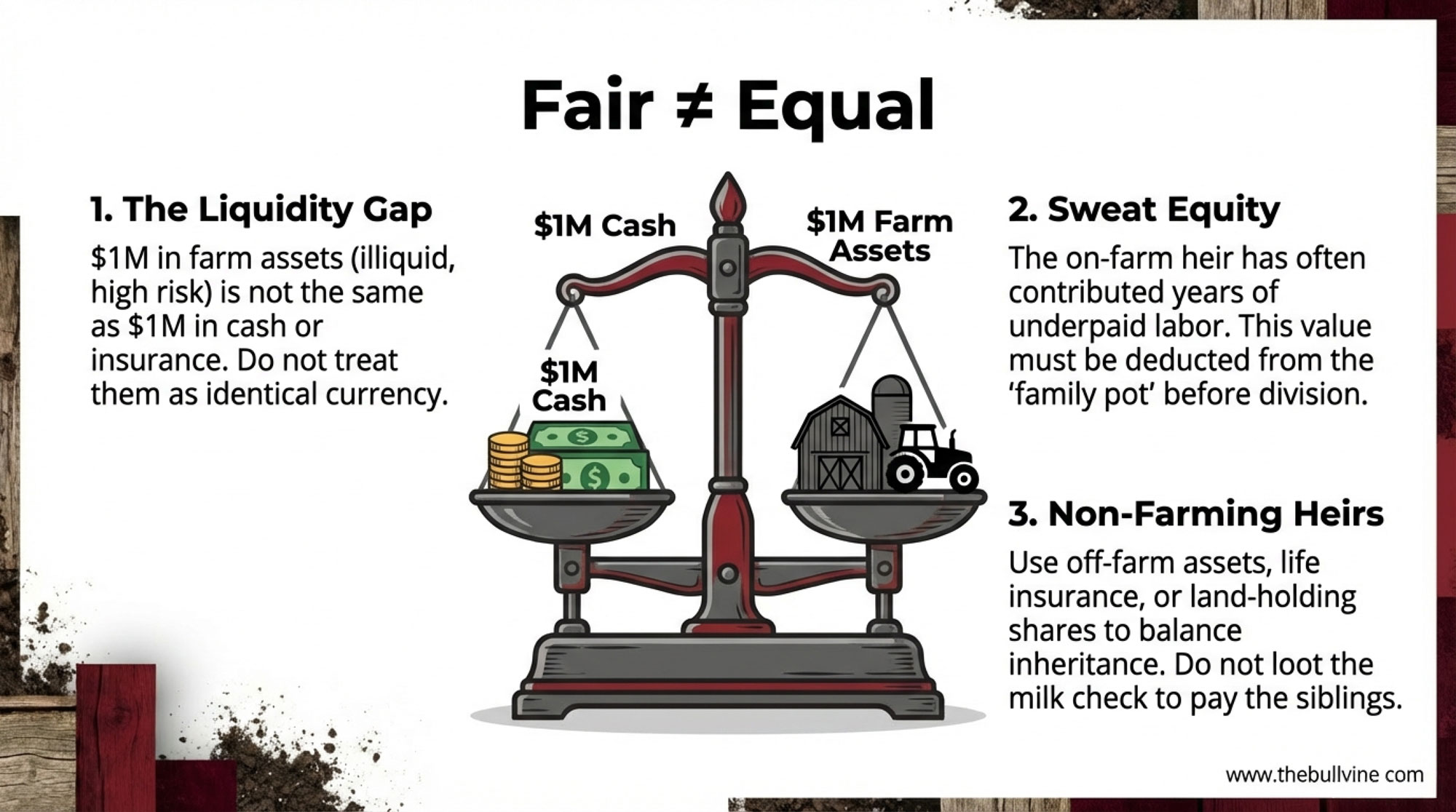

Why “Fair” Doesn’t Always Mean “Equal” in Dollars

Farm Credit Canada has been very straightforward about this. In their article “Family farm transition – is fair always equal?”, transition specialist Rick Roozeboom uses that exact line: a million dollars in farm assets is not the same thing as a million dollars in cash. In their 2024 piece “What’s fair when everyone contributes differently?”, FCC digs into how different kids contribute to the farm—some with labor and management, others by simply being part of the family story—and why treating those contributions identically, in strict dollar terms, can create real problems.

It’s worth noting that some parents still decide, after seeing the numbers, that equal division is the value they care about most—even if that ultimately means the farm will be sold. People like farm‑family coach Elaine Froese, who works full‑time on this, see that choice fairly often. That’s not “wrong.” It just needs to be honest: you’re choosing an exit strategy, not a continuity strategy.

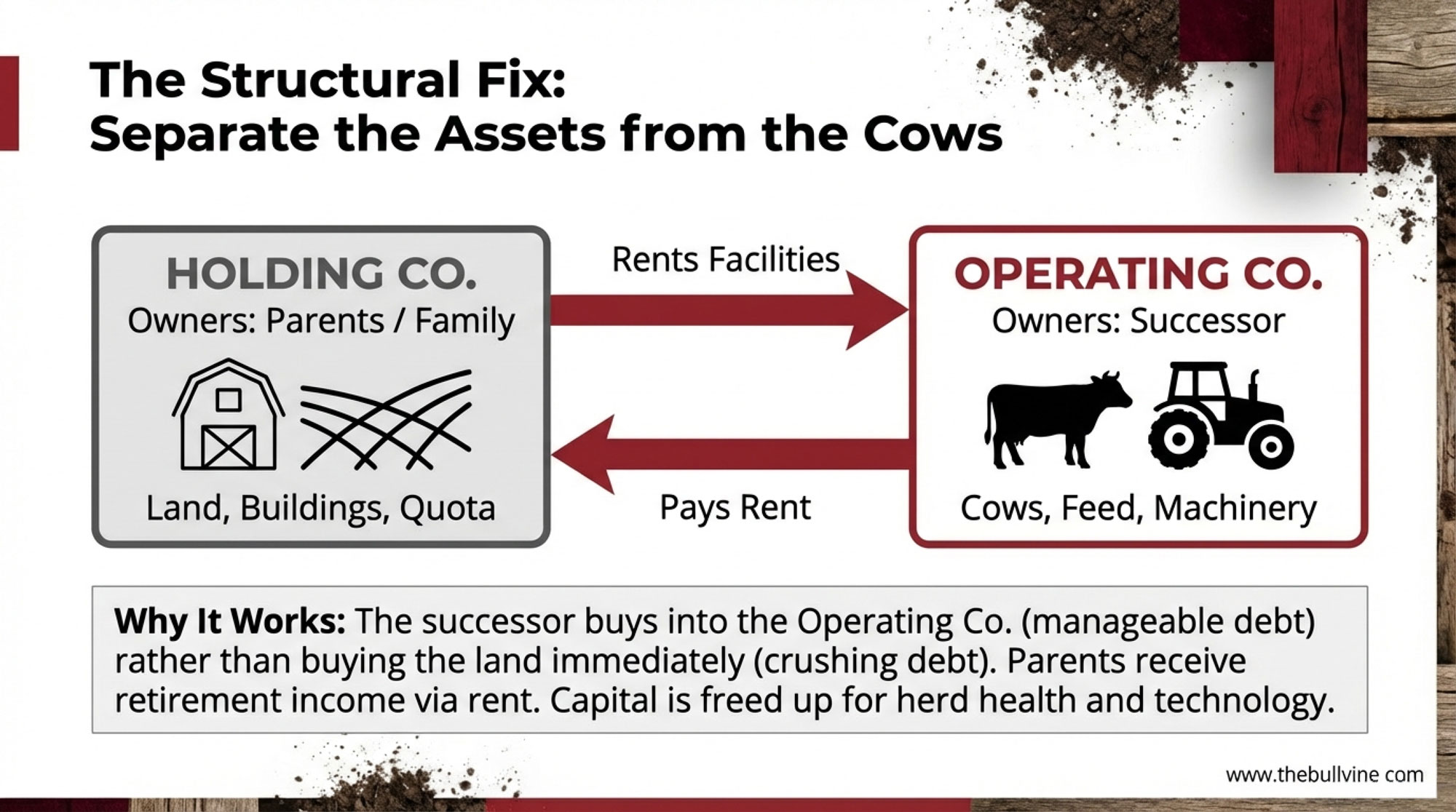

Decision #3: Use Structure to Avoid a Capital Train Wreck

The good news is you’re not limited to the “equal shares at full appraised value” model. There are other ways to structure things so the farming child isn’t crushed and non‑farming children aren’t left feeling shut out.

One Yard, Two (or More) Businesses

In Canadian dairy, especially, you often see accountants and advisors using a holding‑company plus operating‑company model. Firms like MNP and Baker Tilly often discuss this in their farm‑succession resources.

The basic idea goes like this:

- Land, buildings, and quota sit in a holding company or partnership, often owned primarily by the parents and, eventually, by a mix of family members.

- The operating company holds the cows, replacements, feed, and machinery, and runs the day‑to‑day dairy.

- Over time, the successor acquires the operating company through staged share purchases, profit‑sharing, or a combination.

This gives you a few levers to pull:

- Parents can receive retirement income from rent or dividends paid by the holding entity.

- The successor doesn’t have to debt‑load themselves all at once with land, barns, and quota; they can focus capital on keeping cows healthy, improving butterfat levels, managing SCC, and investing in genetics or automation.

- With good advice, you can line this up with tools like the intergenerational rollover and the Lifetime Capital Gains Exemption.

In Ontario and Quebec quota herds, where the value of quota alone can be massive, this kind of structure can be the difference between having a path forward and quietly setting up a forced sale.

Other Tools That Often Get Overlooked

In U.S. herds without quota, you still see some of the same themes:

- Partnerships or LLCs in which the successor buys units over a decade or more, funded partly with profits.

- Land companies that hold farmland, sometimes with both farming and non‑farming siblings as owners, and long‑term leases to the operating dairy.

- Planned growth or diversification—adding cows, custom heifer‑raising, beef‑on‑dairy programs, or on‑farm processing—to create enough cash flow to support a buy‑in and reinvestment.

A 2021 article in Sustainability looking at small U.S. farms (not just dairy) found that producers who combined enterprise decisions with financial risk‑management tools—like insurance, off‑farm income, and contracts—tended to have stronger economic sustainability. That lines up with what many of us see: the farms that think in terms of structure and risk management, not just “who works hardest,” usually have more options when it’s time to transition.

Decision #4: Build a Successor as a Leader, Not Just the Go‑To Worker

Every dairy has someone who knows exactly which cows are in trouble in the transition period, who notices a butterfat dip before anyone else, and who can read a robot alarm in their sleep. They’re often the first person you call when something’s off.

It’s worth noting, though, that being the most reliable worker and being the person who carries the bank meeting, the staff reviews, and the five‑year capital plan are different skill sets.

That Brazilian study I mentioned earlier found that successors with higher absorptive capacity—basically, better at absorbing and using new information—and stronger social networks were more likely to be in place and engaged in management on family farms. Other work on family‑firm resilience suggests that leadership development and adaptability are key to who survives shocks like droughts, price crashes, or major policy changes.

So here’s the question I’d encourage you to ask: “Are we intentionally building a leader here, or are we just giving more jobs to the person who never says no?”

Trial Management with Real Metrics

We already talked about giving the next generation specific areas to run. The key is to pair that with clear metrics and then actually look at them together. In practice, that might be:

- Fresh cow and transition management: track fresh cow health events, early culls, peak milk, and repro performance.

- Cropping: track forage quality (protein, NDF digestibility), yield, and cost per ton of dry matter, then connect that to milk production and butterfat levels.

- People: track turnover, missed shifts, and the consistency with which standard operating procedures are followed.

In many cases, lenders in Wisconsin and Minnesota have said, “Show me how they’ve done when they were responsible, not just when they were helping,” before they sign off on financing a buy‑in. It’s not about being harsh; it’s about giving everyone confidence that the next person can actually drive the ship.

Shifting Real Authority, Step by Step

A lot of extension material, including from Wisconsin and Missouri, discusses moving successors through stages—from employee to enterprise manager to multiple‑enterprise manager to primary operator, and finally to lead owner. Groups like Land For Good emphasize writing down who makes what decisions at each stage.

What’s encouraging is that when families do this on purpose—rather than on the fly—you see the older generation relax a bit because they’re not handing over everything at once. And the younger generation builds confidence because they’re making meaningful decisions before the paperwork changes hands.

| Key Factor | Farms Making It to Gen 3 (16.5%) | Farms at Risk of Dispersal (83.5%) |

|---|---|---|

| Succession Timing | Start serious talks 10–15 years out; parents in 50s, successor in 20s–30s | Wait until burnout, health crisis, or parent age 65+; rushed decisions |

| Successor Development | Off-farm experience + trial management in specific areas with measurable KPIs | No off-farm training; successor does many jobs but leads none; vague accountability |

| Capital Structure | Use holding/operating split, staged buy-ins, or sweat-equity recognition to spread debt load | Full market-value buyout; successor inherits $600–$750 debt per cow |

| Real Authority Transfer | Written plan: who owns what decisions at each stage; regular progress reviews | Vague handoff; older gen still making calls behind the scenes; confusion and resentment |

| Fairness Discussion | Explicit conversations about “fair vs equal”; non-farm kids acknowledged; neutral facilitator | Assumptions left unspoken; non-farm kids blindsided; explodes in lawyers’ offices later |

| Advisory Team | Lawyer, accountant, lender, family coach at same table; coordinated advice | Each advisor in silo; conflicting tax and legal advice; family navigates alone |

| Plan Documentation | Written succession plan reviewed annually; timeline clear; metrics tracked | Vague intentions; no written plan; nobody knows what “done” looks like |

| Contingency for Non-Family Succession | If no family successor emerges, explored non-family paths early (leases, land-access programs) | “We’ll sell when it’s time” or “Nobody wants this farm”; fire-sale dispersal |

Decision #5: Tackle “Fair vs Equal” While Everyone’s Still Talking to Each Other

If there’s one topic that tends to tighten people’s shoulders around the table, it’s fairness. How do you treat non‑farming kids fairly without burying the one who stayed?

Research on family businesses and values makes it clear that “fair” means different things to different family members. The on‑farm child might look at years of lower wages, risk, and sacrifice. The off‑farm child might be thinking, “We grew up in the same house; why is my share smaller?”

FCC has tried to normalize that tension a bit. In their fairness articles, they break it down simply: equal is one version of fair, but not the only one. They highlight tools like:

- Using life insurance or off‑farm investments to help non‑farming kids while directing more farm assets toward the successor.

- Separating land from operations so siblings can share in land ownership while the farming heir controls and builds the operating business.

- Putting numbers on sweat equity—years of below‑market wages and capital contributions—so the successor’s extra skin in the game isn’t invisible.

As many of us have seen, families that talk through this with a neutral person—a mediator, coach, or extension specialist—tend to come out with solutions that everyone can live with. It doesn’t make every conversation easy, but it makes them a lot less explosive.

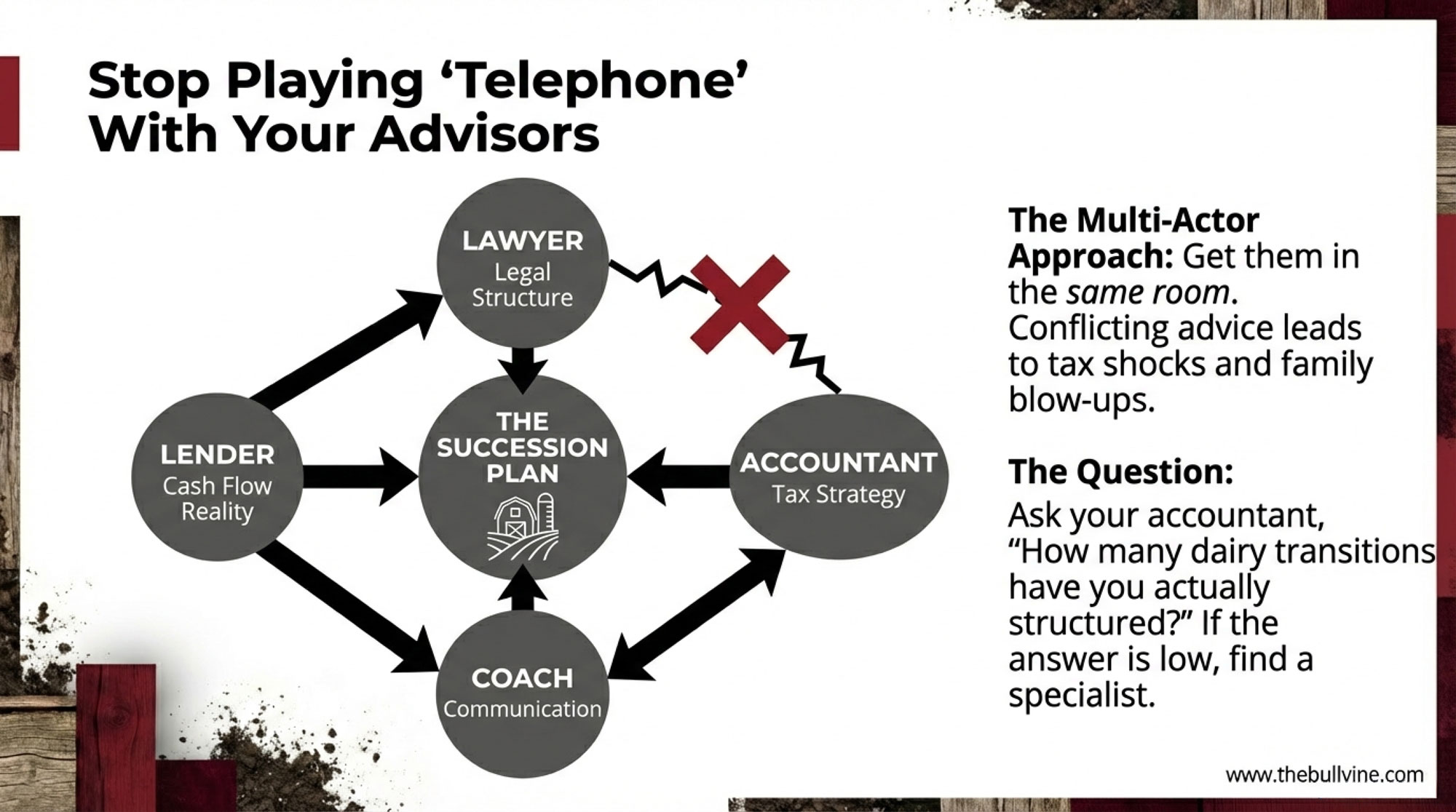

Decision #6: Bring a Real Advisory Team Around the Same Table

One thing Teagasc in Ireland has really leaned into—and I think it’s worth watching from this side of the ocean—is the idea of coordinated advisory teams. They call it the Multi‑Actor Succession Teams approach.

Instead of the family bouncing between their Teagasc advisor, their accountant, and their solicitor, each giving advice in isolation, Teagasc arranges meetings where everyone sits together, looks at the same facts, and works toward a plan the family can actually implement.

The Irish government even backs this up with the Succession Planning Advice Grant. That grant can contribute up to 1,500 euros toward eligible professional costs—lawyers, accountants, and so on—for families who go through a structured succession process.

We don’t have that exact grant in Canada or the U.S., but the principle still applies. In FCC stories and in a lot of North American advisory work, the farms that make the cleanest transitions tend to have a team that looks something like:

- A lawyer who does farm transfers regularly, not just basic wills.

- An accountant who understands farm tax rules, intergenerational rollovers, and the quirks of quota or depreciation.

- A lender who’s seen both good and bad transitions and can talk plainly about what the balance sheet can support.

- A family‑business coach or mediator who keeps the conversation moving and honest.

- A financial planner who helps the senior generation turn this plan into a retirement that doesn’t depend entirely on guilt or generosity.

What’s interesting is that when you get these folks in the same room—even just once or twice—you cut down a lot of the “he said / she said” between offices. You also tend to catch conflicts between tax ideas, legal structures, and bank policies before they become expensive mistakes.

Decision #7: If There’s No Family Successor, Don’t Assume “Sell Next Month” Is the Only Path

We also have to be honest: sometimes, nobody in the next generation wants to run the dairy. Or they want to stay connected as owners, but not in the day‑to‑day.

In that situation, it’s easy to feel like the only choices are: run yourself into the ground or sell everything at once. But there’s some interesting work happening here, too.

The Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development has published several papers on land‑access and transition policies. One 2020 study examined “land access policy incentives”—such as state tax credits and USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program–Transition Incentives Program—and how they’re being used to transfer land to younger and beginning farmers through long‑term leases or sales. A 2024 evaluation of the Transition Incentives Program highlighted its role in helping older farmers transition CRP land to new operators in a more controlled way.

And Tennessee’s succession workbook explicitly says that if there’s no interested or prepared family successor, it’s worth looking at non‑family options—long‑time employees, young neighbors, or other beginning farmers—through structured leases or phased sales.

So in many cases, your choices might look more like:

- Gradually leasing facilities and herd to a non‑family operator with a clear agreement.

- Selling land but keeping some involvement in the herd or youngstock for a few years.

- Working with a land‑link program or policy incentive to bring in a new operator under defined terms.

That’s not going to fit every situation, but it’s better than assuming there are only two buttons to push: “ignore it” or “disperse immediately.”

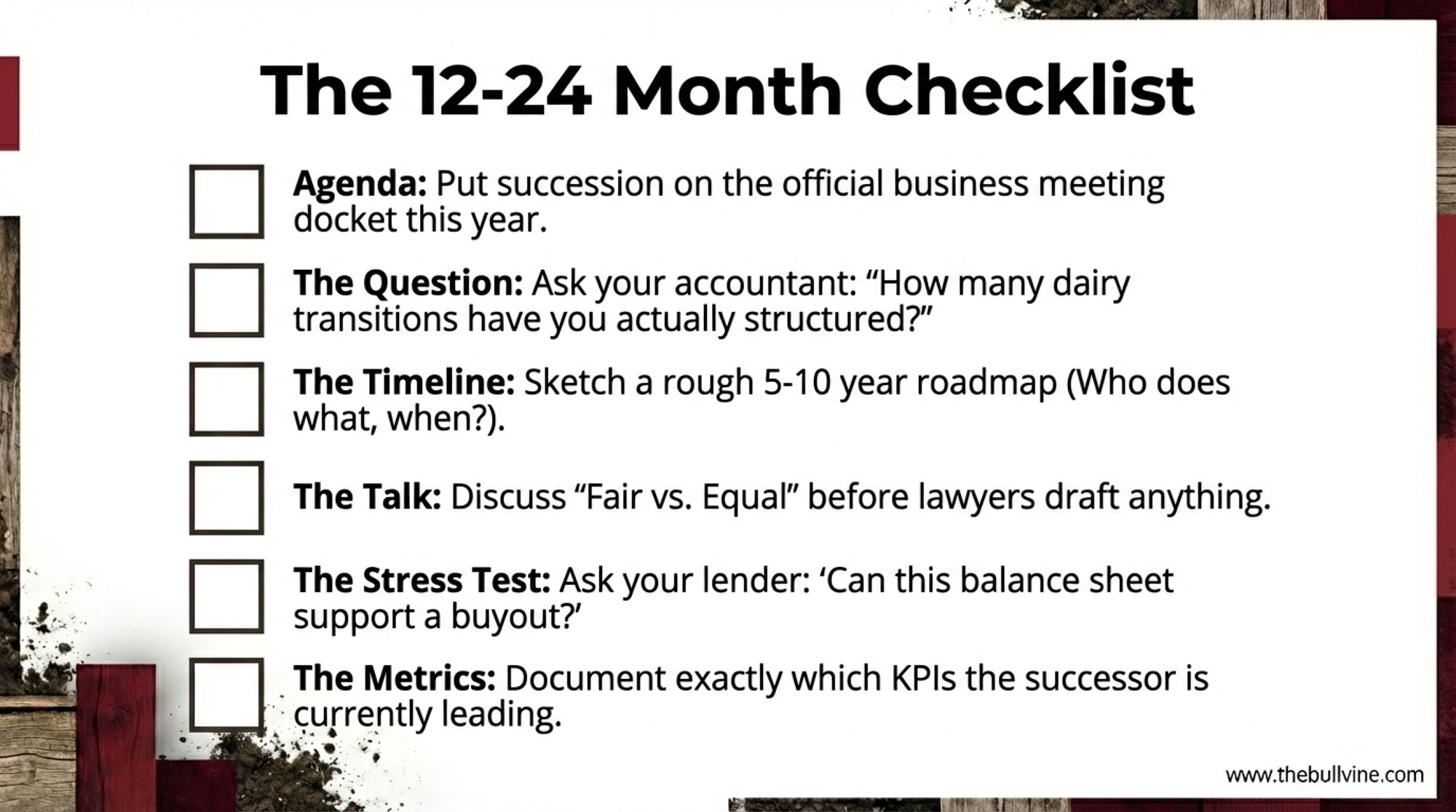

A Realistic 12–24‑Month Game Plan

If you’re thinking, “This is all fine, but we’re not a decade out, we’re three to five years out,” you’re not alone. A lot of families are in that position. The goal in that case isn’t to build the perfect binder. It’s to move from “vague intentions” to a written, realistic plan.

Here’s a simple roadmap that I’ve seen work on real farms:

1. Put Succession on the Farm Agenda This Year

It sounds almost too basic, but the first step is to stop treating succession as a late‑night worry and start treating it as business. Tools from OMAFRA, New Brunswick’s farm‑transition checklists, and Tennessee’s workbook all include question sets that ask, for example, “Who wants to be involved and in what way 10–15 years from now?” and “What do you want this farm to look like then?”

In many cases, just getting those answers written down is a big step forward.

2. Ask Your Advisors a Very Direct Question

At your next accountant or lawyer visit, try this:

“How many farm successions have you helped structure in the last five years, and what kinds of structures did you use?”

If the answer is “not many,” that doesn’t mean they’re a bad fit for everything. But it’s a sign you may want to bring in someone who spends most of their time on farm transfers, even if it’s just for a few key meetings.

A lot of the train wrecks I’ve seen weren’t because the people involved were careless; they were simply working with advisors who didn’t specialize in the complexity of farm assets, quota, and family dynamics.

3. Sketch a Rough Timeline

You don’t have to frame this on the wall, but it helps to see it. Write down:

- Your age

- The age of any realistic successor

Then ask:

- “When would I like to be mostly out of day‑to‑day decisions?”

- “When does this person need to be fully in charge for this to feel responsible?”

Alberta’s transition planning guide and other resources offer examples of 10–15‑year transition timelines. Even if you only have five years, putting rough mileposts down—“by Year 2 they handle cropping decisions; by Year 4 they’re lead on fresh cows and people; by Year 5 we finalize ownership changes”—gives everyone something concrete to work toward.

4. Start the Fair vs Equal Talk Before Lawyers Draft Anything

If you can, bring in a neutral facilitator—an extension specialist, a mediator, or a farm‑family coach—and have a meeting with all children, farming and non‑farming.

Some good questions:

- “What would feel fair to you if you’re the one farming here?”

- “What would feel fair if you’re not farming but want to stay connected?”

- “What worries you most about how this might be handled?”

Research on family climate and succession planning suggests that families who discuss expectations openly, rather than leaving them implied, tend to have smoother transitions and fewer broken relationships in the long run.

5. Document Where the Successor Already Leads

If someone’s already making key calls, get that down on paper.

Make a short list:

- Decisions they currently own (transition‑period protocols, breeding program, staff scheduling, major purchases).

- The numbers you’re using to judge success (milk per cow, butterfat and protein levels, SCC trends, repro KPIs, heifer inventory, feed cost per cwt).

That list isn’t just for the bank. It’s for you too. It shows you where you can start stepping back—and where you may need to push them to take more responsibility.

6. Sit Down with Your Team and Ask How to Avoid the Capital Crunch

When you’ve got your accountant, lawyer, lender, and maybe a coach at the table, put this question on the flip chart:

“If we don’t want to rely on a full market‑value buyout to be fair, what options do we have that you’ve seen work for dairies like ours?”

In many cases, that’s when ideas like holding/operating structures, land companies, staged share purchases, or long‑term leases with built‑in buyout formulas start to surface. The mix that makes sense for a 90‑cow tie‑stall in New Brunswick won’t be the same as for a 1,200‑cow freestall with robots in Wisconsin, but the goal is the same: keep capital demands aligned with what the business can support.

7. If There’s No Family Successor, Explore Non‑Family Paths on Purpose

If no family member wants to run the dairy, consider whether a longtime employee or a young neighboring producer could be part of a structured transition plan. Research on land‑access policy incentives and the Transition Incentives Program shows that staged sales and long‑term leases are already being used across North America to help older farmers exit without simply putting up a “For Sale” sign and walking away.

| Timeline | Step | Owner | Key Output | Success Looks Like |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 (This Year) | 1. Put Succession on the Farm Agenda | Family | Written answers to “Who wants in? What does the farm look like 10–15 years out?” | Everyone has read the workbook questions; one family meeting completed |

| 2. Ask Your Advisors a Direct Question | Parent + Advisor | List of advisors with farm-succession experience | You have at least one advisor who’s structured 5+ farm transitions in the last 5 years | |

| 3. Sketch a Rough Timeline | Family | One-page timeline with ages, transition milestones, key decision dates | You can see when the successor needs to be fully in charge; you know when you want to step back | |

| Year 2 | 4. Start the Fair vs Equal Talk | Family + Facilitator (optional) | Written record of what each child views as fair; areas of agreement & concern | Non-farming kids feel acknowledged; farming successor feels supported; no surprises later |

| 5. Document Where the Successor Already Leads | Family + Successor | List of current decisions owned by successor; KPIs used to measure success | You have 3–5 areas where the successor is fully responsible and hitting targets | |

| 6. Meet with Your Team & Address the Capital Question | Family + Lawyer + Accountant + Lender | Outline of 2–3 structures that could work (holding/operating, staged buy-in, land lease, etc.) | You understand which structure fits your farm; you know what equity needs to move and when | |

| Year 2–3 | 7. If No Family Successor, Explore Non-Family Paths | Family + Land-Link or Extension | Preliminary conversations with potential long-term employees or neighboring operators | You have a Plan B if the family route doesn’t work; you’re not forced into a fire-sale dispersal |

| Outcome by Month 24 | Written Succession Plan | Family + Advisors | Final plan document (2–5 pages); annual review schedule set | You have a one-page summary everyone agrees on; annual check-in on the calendar; confidence that this farm will be here in 20 years |

The main thing is to look at this while you still have energy and flexibility—before age or burnout makes the decision for you.

Most of us have stood by the ring at a dispersal sale and felt that twist in our gut watching cow families, genetics, and years of work roll out the lane. Sometimes that’s the right choice—especially when it’s planned and keeps the family whole.

But if your hope is to see cows in those barns and milk leaving your lane under your family’s name into the next generation, the data and the lived experience line up on this: the families who make it into that 16‑odd percent don’t get there by luck. They start earlier than feels comfortable. They treat “equal at full value” as something to stress‑test, not a default. They build a successor who can actually lead, not just work. They use structures that reflect today’s capital load and margins. And they get a real team around the table instead of trying to carry it all alone.

You don’t have to overhaul everything by next spring. But if sometime this year you say, “Okay, who might realistically succeed us?”, sketch a rough timeline, and ask your advisors how to do this without crushing the farm, you’ll be ahead of where most families start.

And from what many of us have seen, that’s usually how good transitions begin—not with a perfect binder, but with one honest conversation, a few real numbers on the page, and a family deciding they’d rather write their own odds than live by someone else’s statistic.

Key Takeaways

- The survival math is brutal: Only about 16.5% of dairy farms make it to a third generation—and weak or late succession planning is one of the biggest reasons why.

- “Equal at full value” can quietly kill the farm: A traditional buyout can load $600–$750 of debt per cow onto the farming heir, leaving almost nothing for cows, barns, genetics, or the next bad year.

- The 16.5% start earlier and build leaders: Families who beat the odds begin serious transition talks a decade out, give successors real management responsibility (with measurable outcomes), and use off‑farm experience as free training—not a threat.

- Fair doesn’t have to mean equal in dollars: Sweat equity recognition, holding/operating structures, staged buy‑ins, and land‑lease arrangements can balance retirement, fairness, and herd survival without forcing a fire sale.

- A real team beats a scattered one: Getting your accountant, lawyer, lender, and a family coach around the same table—like Teagasc’s Multi‑Actor Succession Teams—helps you dodge tax traps, catch conflicts early, and keep relationships intact.

Executive Summary:

Only a small slice of dairy farms—roughly that 16.5%—make it to a third generation, and it’s not because the rest didn’t care enough about legacy. This article digs into what separates the survivors, combining family‑business research, FINBIN 2024 dairy numbers, and fresh work on farmer stress and leadership to show where most plans quietly break down. You’ll see how a “fair” full‑value buyout can stack $600–$750 of debt on every cow, why that’s so dangerous in a 2%‑ROA business, and how structures like holding/operating companies and staged buy‑ins can keep both retirement and reinvestment on the rails. We walk through the timing piece—starting conversations while parents still have a decade to work, using off‑farm experience as training, and giving successors real management oxygen instead of just more chores. There’s a straight‑talk section on “fair vs equal” for farming and non‑farming kids, and how coordinated advisory teams (the kind Teagasc and FCC are pushing) help you avoid tax shocks and family blow‑ups. The article also opens the door to non‑family succession routes and land‑access programs when there’s no heir in the barn. You’ll finish with a concrete 12–24‑month checklist to test your own plan and a clearer sense of whether you’re quietly planning a continuity story—or an eventual dispersal.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The Family Dairy Time Bomb: Why 83.5% of Operations Fail by the Third Generation – Gain a five-step readiness audit to defuse transition risks before they fracture your family’s equity. This guide delivers the financial structures and communication protocols needed to move your succession plan from theory into a stable, operational reality.

- Decide or Decline: 2025 and the Future of Mid-Size Dairies – Capture a 2025 positioning strategy that maps expansion against optimization to protect your long-term margins. This analysis exposes the debt-ratio discipline and regional shifts required to keep your mid-size operation competitive in an era of consolidation.

- From 4-H Project to 20 All-Americans: The 28-Year-Old Proving Your Succession Plan Is Already Dead – Leverage the elite-level performance advantage of high-index genetics and real-time monitoring to out-perform traditional management curves. This profile delivers unconventional, data-driven methods used by industry mavericks to compress succession timelines and secure your herd’s future.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!