Quota costs CA$2.4M in Canada. But American farmers pay the ultimate price: their farms.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Canadian dairy farmers plan five years ahead, while American producers pray to survive five months—that gap widened on October 30, when Canada announced a 2.3% price increase as U.S. prices crashed by 11.44%. Canada’s supply management system guarantees profitability but demands CA$2.4-5.8 million in entry fees, offering just 8 new-farmer positions annually per province, while 88% of farms transfer within families. America’s “free” market eliminated 1,420 farms in 2024, aided by cooperatives like DFA, which now own processing plants and profit from the same low prices that destroy their members. Both systems hemorrhage taxpayer money—Canada openly through CA$444 annual household premiums, America secretly via $2.7 billion in failing subsidies. The brutal math: by 2044, America will have fewer than 10,000 dairy farms while Canada maintains stability for an increasingly exclusive club. Solutions exist that combine Canadian predictability with American accessibility, but require farmers to stop defending broken systems and start wielding their political power like Quebec dairy did—they didn’t ask nicely; they demanded protection and got it.

You know, when the Canadian Dairy Commission announced its 2.3255% farmgate milk price increase for February 2026 last Wednesday, I couldn’t help but think about the conversations I’ve been having with producers on both sides of the border. Here’s what’s interesting—American farmers had just watched their milk prices drop 11.44% year-over-year, based on August USDA data. But this isn’t just another price comparison story, not really.

What I’ve found after digging into both systems these past few weeks is… well, it challenges a lot of assumptions we tend to make. Canadian farmers enjoy remarkable stability through supply management, that’s absolutely true. But there’s something they don’t talk about much at Holstein Canada meetings or the Royal Winter Fair—the generational entry barriers that are quietly threatening their long-term sustainability.

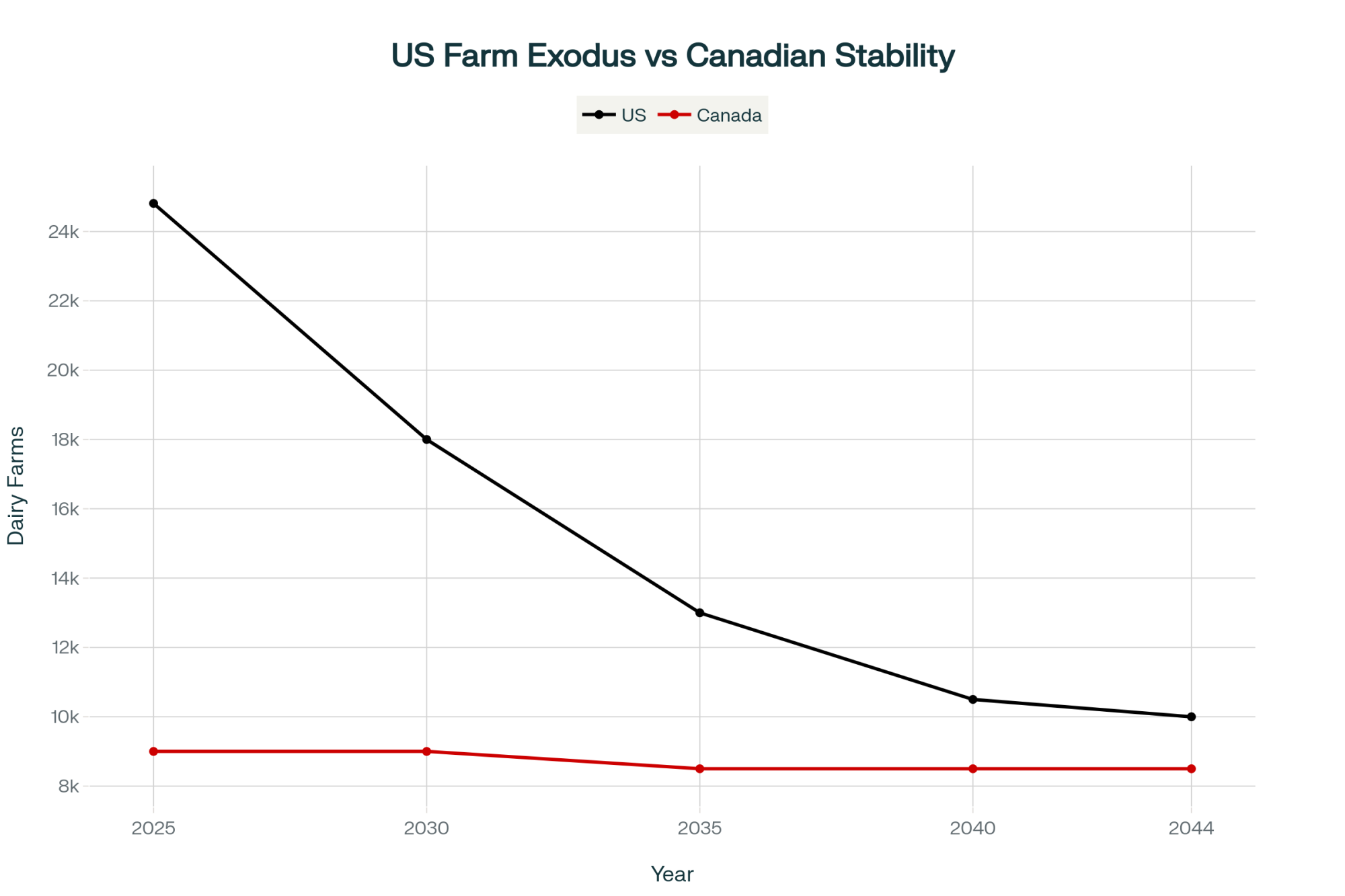

Meanwhile, American producers keep telling me about the “freedom” of open markets. Yet we’re watching 1,420 farms close each year, according to the latest USDA census data. At this rate—and the math here is pretty sobering—we’re looking at fewer than 10,000 U.S. dairy operations by 2044. That’s fewer farms than Canada has today, if you can believe that.

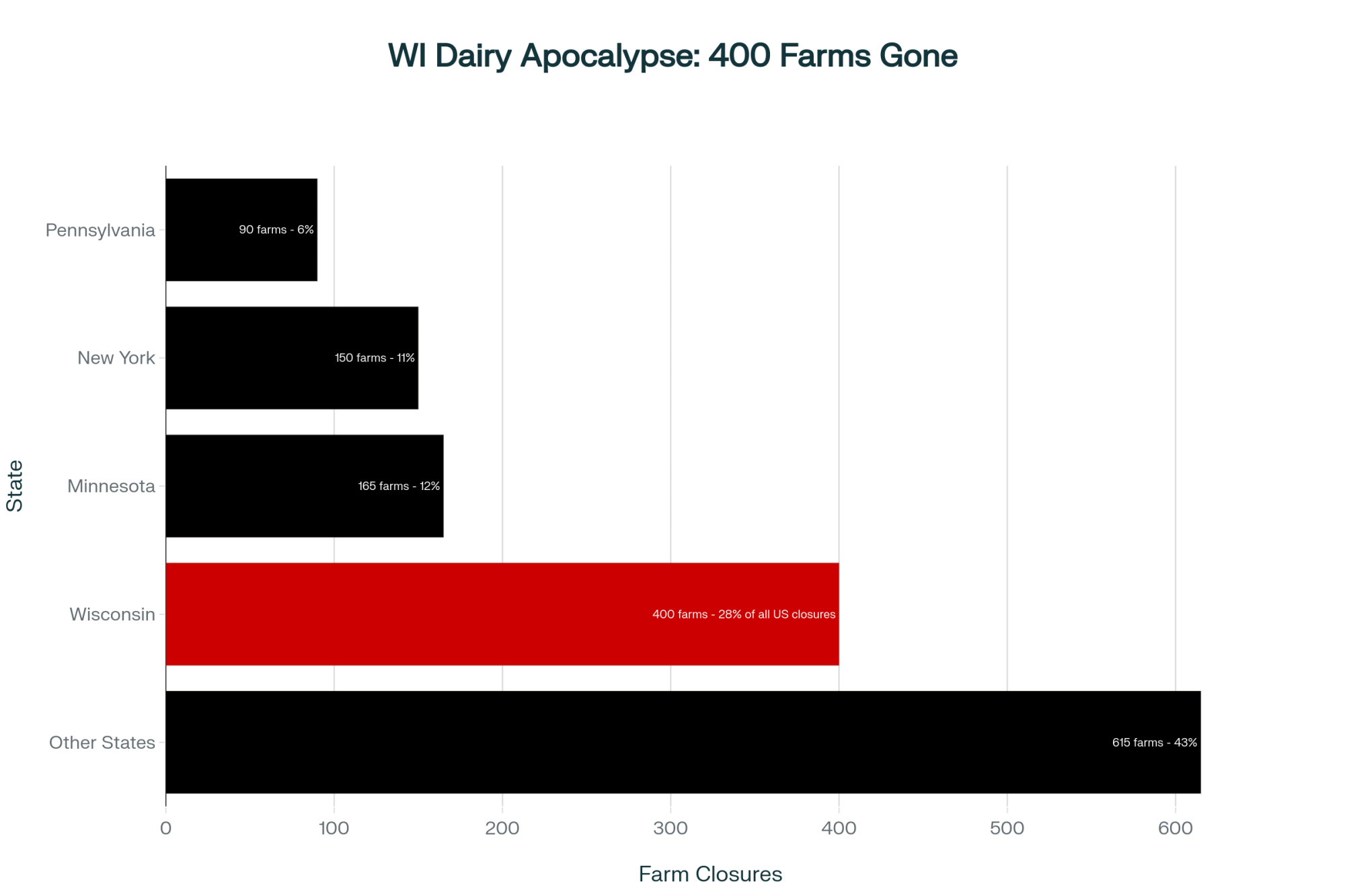

“We keep being told markets will sort it out. But after losing 400 farms in our state last year, I’m starting to wonder if the market’s solution is just to sort us out of business.” — Wisconsin dairy farmer reflecting on the 2024 closures

Part I: The Canadian System—Stability at What Cost?

How Supply Management Works: Business Planning vs. Price Taking

Looking at Canada’s approach, what strikes me first is the philosophical foundation. You probably know this already, but supply management—established through provincial legislation like Ontario’s Farm Products Marketing Act—operates on a straightforward principle. Dairy farmers are legitimate business enterprises deserving predictable returns.

Here’s what’s fascinating about the CDC’s quarterly cost-of-production formula. It includes everything you’d expect in a real business calculation—feed costs (which jumped 8.7% in their latest review period), labor, depreciation on that new mixer wagon you bought, interest paid on operating loans, and even return on equity. When those costs rise, prices adjust through their transparent formula: 50% of index cost changes plus 50% of consumer price trends.

This creates dramatically different planning horizons than what we see south of the border. Research from the University of Guelph suggests that Canadian dairy farmers typically make facility upgrade decisions with a 5-7 year outlook. As many Canadian producers have told me, their milk price adjustments typically stay under 1% annually, based on CDC historical data, so they can actually plan. That guaranteed 2.3% increase? That’s the predictability American farmers can only dream about.

The Hidden Entry Crisis: When Protection Becomes Exclusion

But here’s something that doesn’t come up much at Dairy Farmers of Canada meetings—and it’s worth noting. Those quota values are running CA$24,000 per kilogram in Ontario, where it’s price-capped, according to the provincial marketing board. In Alberta? Try CA$58,000 per kilogram on the open exchange, based on Alberta Milk’s August 2025 reports.

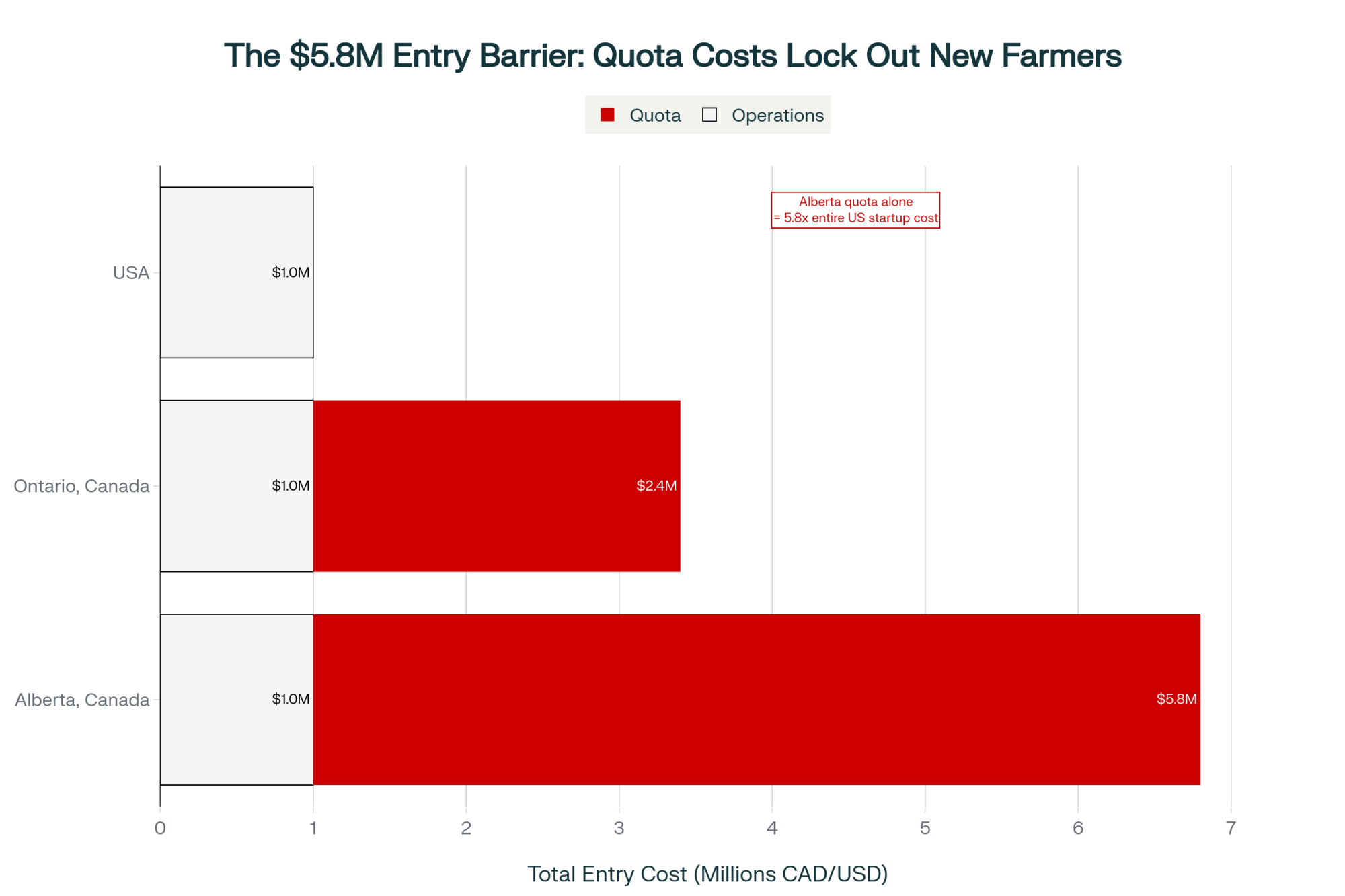

So let me do the math for you. A modest 100-cow operation needs CA$2.4-5.8 million just for production rights. That’s before you buy a single cow or pour a single yard of concrete.

The provincial “new entrant” programs supposedly address this. Let me share what they actually offer, based on current program documents I’ve been reviewing:

- Ontario’s NEQAP: 8 positions available annually for the entire province (and 2 of those are reserved for organic)

- British Columbia’s GEP: They’re running an accelerated program, clearing a 20-year backlog at 8 entrants per year

- Quebec: Similar story—limited slots, multi-year waiting lists according to Les Producteurs de lait du Québec

Farmers in BC’s program report waiting periods of 10-15 years, based on media reports and program documentation. Even then—and this is what really gets me—successful applicants often receive a quota for just 25-30 cows. That’s not exactly a path to economic viability when the provincial average is pushing 100 head.

What’s really telling is that the vast majority of Canadian dairy farms transfer within families, according to Statistics Canada’s agricultural census data. It’s becoming something you inherit rather than something you choose. Even the National Farmers Union, which generally supports supply management, admitted in their 2019 policy brief that these programs are “fundamentally inadequate and require major reforms.”

The True Cost to Consumers and Society

You know, Canadian supply management costs consumers approximately CA$444 annually per household through higher retail prices, according to the Conference Board of Canada’s 2023 dairy sector analysis. That’s a direct, transparent wealth transfer totaling about CA$3 billion yearly, based on academic estimates from the University of Saskatchewan and Fraser Institute.

Critics hate it, but at least Canada’s honest about the cost. You’re paying more for milk, and that money goes directly to keeping farmers in business. No hidden subsidies, no complex government programs—just straightforward consumer-to-farmer transfer.

Part II: The American System—Freedom to Fail

Open Access, Constant Crisis

Now, the U.S. system—no quota barriers at all. Got capital? You can start milking tomorrow. But that theoretical openness… well, let me share some numbers from USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service that paint a different picture:

- 2024 farm closures: 1,420 operations lost (that’s a 5% annual decline)

- Wisconsin alone: 400 dairy farms gone, according to Wisconsin DATCP license data

- Five-year total: Nearly 10,000 farms have disappeared since 2019

- Chapter 12 bankruptcies: Up 55% in 2024, based on Federal Reserve agricultural finance data

As Tonya Van Slyke from the Northeast Dairy Producers Association put it in a recent interview: “Dairy farmers are price takers. The Federal Milk Market Order controls what producers get paid for their milk.”

Think about that for a minute. You can have the best somatic cell count in the county, run your repro program perfectly, and manage your transition cows like a textbook operation. But if Class III crashes because there’s too much cheese in cold storage? Well, you’re taking that hit.

I know Wisconsin producers who literally check CME cheese prices on their phones during morning milking, wondering if next month brings another crash. That’s not business planning—that’s survival mode.

The DMC Illusion: Why Safety Nets Have Holes

The Dairy Margin Coverage program—that’s supposed to be America’s safety net, right? Here’s what’s interesting: it hasn’t triggered a payment in 17 months as of October 2025, even though I know plenty of farmers facing severe financial stress.

The formula, as described in FSA’s calculation methodology, considers only corn, soybean meal, and premium alfalfa hay. Labor costs going through the roof? Fuel prices? Is California requiring new environmental compliance equipment? DMC doesn’t see any of that.

What really gets me is what’s happening with succession planning. Agricultural transition consultants report that farm kids who love agriculture, grew up showing at county fairs, have all the skills—they’re going to college and choosing ag lending or veterinary medicine instead of coming home. Why? Because they watched their parents stressed about milk prices for 20 years and thought, “I’m not putting my kids through that.”

The Structural Failure of American Cooperatives: DFA’s Transformation

Here’s where the American system reveals its most fundamental flaw—and this is something we need to talk about more openly. It’s the structural failure of the cooperative model when cooperatives become processors.

The transformation of Dairy Farmers of America illustrates exactly how the system breaks when a cooperative’s business interests as a processor diverge from its members’ interests as farmers.

In May 2020, DFA acquires 44 Dean Foods processing plants for $433 million out of bankruptcy, according to U.S. Bankruptcy Court filings. Overnight, they become both the nation’s largest milk supplier and processor. This created what multiple class-action lawsuits filed in Vermont and other states describe as an “inherent conflict of interest.”

Think about the structural contradiction here. As a cooperative, DFA theoretically exists to maximize returns to farmer-members. But as a processor, DFA profits from buying milk as cheaply as possible. The cooperative’s processing division literally benefits from the same low prices that destroy its members’ operations.

The numbers from the Vermont lawsuit reveal the scope of this structural failure. Before acquiring Dean’s plants, DFA sold over 50% of its members’ milk to third-party processors. By 2021, according to court documents, they were selling 66% of their shares to themselves. When milk prices crashed 30-40% in 2023—and USDA data confirms approximately a 35% decline—DFA’s processing plants captured margin expansion while member farmers absorbed losses.

And here’s what I think is crucial to understand: this isn’t a management failure or the work of bad actors. It’s a fundamental structural flaw. Once a cooperative owns processing assets, its economic incentives become adversarial to its own members. The business model that should protect farmers becomes the mechanism for extracting value from them.

I’ve talked to DFA members who understand this perfectly. They need market access, but their own cooperative has structurally transformed into their competitor. The organization collecting their dues and claiming to represent them profits when they suffer. That’s not a cooperative anymore—it’s a vertically integrated processor with a cooperative facade.

Regional Variations: Scale Doesn’t Save You

You know, this isn’t just a Wisconsin-Pennsylvania story. Down in the Texas Panhandle, where operations are milking 3,000-cow herds, the economics look different, but the fundamental problems persist.

Large-scale operators in that region tell me they’ve got scale, efficiency, and cost per hundredweight that beats almost anyone. But when milk prices drop below $15? Even they bleed. The only difference is that they can bleed longer than the 200-cow farm.

Looking west to California and Idaho, where some operations are milking 10,000-plus cows, these mega-dairies have negotiating power that smaller farms lack. But one Idaho producer managing 8,500 cows told me at the Western States Dairy Expo, “We’ve got economies of scale everyone talks about, but our regulatory compliance budget alone would operate five Wisconsin farms.”

And down in Arizona and New Mexico? The water rights battles are getting brutal. One New Mexico producer with 4,200 cows shared something that stuck with me: “We’re efficient as hell on paper—lowest cost per hundredweight in the nation some months. But what happens when water allocations are cut by 30% and hay prices double because everyone’s irrigation is restricted? Those efficiency numbers don’t mean much.”

Texas A&M agricultural economists have documented what happens when a 5,000-cow dairy goes under—millions in economic impact rippling through rural communities. The big operations might survive longer, but volatility eventually gets everyone.

Hidden Subsidies: The “Free Market” Myth

Here’s something we don’t talk about enough. American dairy receives billions in government support, but we just call it something else. Based on USDA Economic Research Service data:

- Dairy Margin Coverage payments: $2.7 billion net from 2019 to 2024

- Federal Milk Marketing Order price supports (harder to calculate, but substantial)

- Export promotion programs through the Dairy Export Council

- Regular disaster assistance and emergency payments

- Subsidized crop insurance that reduces feed costs

We call these “risk management tools” rather than “subsidies.” Lets politicians claim they support “free markets” while channeling taxpayer money to agriculture.

The difference from Canada? Well, Canadian intervention actually achieves its stated goals—stable farm numbers, farmer income security, and functioning rural communities. American intervention? We keep losing farms despite billions in support. Makes you wonder who these programs really benefit.

| Metric | Canadian Supply Management | U.S. ‘Free Market’ |

|---|---|---|

| Farm Exits (Annual) | 100-150 (1-2%) | 1,420 (5%) |

| Entry Cost (100 cows) | CA$2.4-5.8M quota + operations | $800K-1.2M operations only |

| Price Volatility | <1% annual variation | 30-40% swings possible |

| Planning Horizon | 5-7 years typical | 90 days common |

| Consumer Cost | CA$444/household/year premium | Hidden via taxes/programs |

| New Entrants/Year | 50-80 nationally (limited slots) | Unlimited (but unsupported) |

| Price Trend 2024-26 | +2.3% guaranteed increase | -11.44% decline (volatile) |

| Government Support | Transparent consumer transfer | $2.7B hidden subsidies (DMC) |

| Farm Stability | Predictable, stable income | Survival mode, constant crisis |

| Succession Rate | 88% family transfer | Farm kids choose other careers |

| 2044 Projection | ~8,500 farms (stable) | <10,000 farms (-60%) |

Part III: Finding Common Ground—Lessons from Both Systems

What Actually Works: Three Leverage Points

Through all this research and talking with farmers across North America, I’m seeing three genuine leverage points for producers seeking stability without Canada’s entry barriers:

1. Direct-to-Consumer Sales Twenty-eight states now allow raw milk sales in some form, according to the Farm-to-Consumer Legal Defense Fund’s 2025 tracking. Producers engaging in direct sales report getting $8-12 per gallon—that’s a 400-600% premium over conventional farmgate prices. As many Pennsylvania producers have told me, moving 20% of production to direct sales changes the entire negotiation dynamic with cooperatives.

2. State-Level Political Organization Vermont Senator Peter Welch chairs the Senate Agriculture subcommittee specifically because dairy farmers in his state vote as a coordinated bloc. With only 300-400 dairy farms, Vermont shows what’s possible when farmers organize strategically. If Pennsylvania’s 6,130 dairy farms voted together on dairy issues, they’d own rural policy in that state.

3. Forward Contracting and Risk Management University of Wisconsin-Extension research on risk management consistently shows farms using comprehensive tools—forward contracts, futures hedging, options strategies—achieve significantly more stable margins. Yet adoption remains minimal because, honestly, when you’re checking milk prices daily just hoping to survive the month, learning about put options feels pretty theoretical.

Vermont’s Failed Organizing Attempt: The Missing Legal Framework

Back in the early 2000s, Vermont dairy farmers tried something interesting, as documented in agricultural organizing literature. The Dairy Farmers Working Together movement organized roughly 300 producers, representing about a third of Vermont’s milk production, according to Vermont Extension’s historical accounts. They thought that if they had enough milk, the co-ops would have to negotiate.

But here’s what happened—they just got ignored. No legal framework forced processors to negotiate. The movement collapsed within two years. It showed that a voluntary organization without legal teeth doesn’t work against concentrated processor power.

Learning from New Zealand: A Third Way?

Looking at international models, something is interesting happening in New Zealand. Fonterra—their massive cooperative that handles about 80% of NZ milk according to their 2024 annual report—provides forecast milk prices 18 months out without any quota system.

Their August 2025 forecast came in at NZ$10.15 per kilogram of milk solids (roughly US$21 per hundredweight), with a range of $10.10-10.20. That’s a 1% variance window. No quota to buy, no barriers to entry, just coordinated supply forecasting and transparent pricing.

The Kiwi approach demonstrates you don’t need government protection if you have collective discipline and transparent communication.

Quick Comparison: System Outcomes

| Metric | Canadian Supply Management | U.S. “Free Market” |

| Farm Exits (Annual) | ~100-150 (1-2%) | 1,420 (5%) |

| Entry Cost (100 cows) | CA$2.4-5.8M quota + operations | $800K-1.2M operations only |

| Price Volatility | <1% annual variation | 30-40% swings possible |

| Planning Horizon | 5-7 years typical | 90 days common |

| Consumer Cost | CA$444/household/year premium | Hidden via taxes/programs |

| New Entrants/Year | 50-80 nationally | Unlimited (but unsupported) |

The Projected Timeline: Where This All Leads

If current trends continue—and there’s no reason to think they won’t—here’s what we’re looking at:

U.S. Dairy Farm Projections (5% annual attrition from USDA data):

- 2025: 24,811 farms (current)

- 2030: ~18,000 farms

- 2035: ~13,000 farms

- 2040: ~10,500 farms

- 2044: <10,000 farms

Canadian Projections:

- Maintaining 8,000-9,000 farms through 2040

- But increasing concentration as new entrants can’t access

- Average herd size is climbing steadily

- Small operations selling quota to larger neighbors

Both trajectories lead to the same place—just at different speeds and with different pain levels along the way.

Key Takeaways for Dairy Farmers

Based on everything I’ve learned researching this piece, here’s what I think farmers need to consider:

For Canadian Farmers:

- Defend supply management hard—that 2.3% guaranteed increase is stability American farmers would kill for

- Push for real new entrant reforms—8 positions annually won’t sustain your industry long-term

- Consider quota leasing models instead of ownership—maintains stability without the CA$2.4 million entry barrier

- Watch the generational transfer issue—if young farmers can’t enter, the system eventually collapses from within

- Prepare for continued trade pressure—international partners aren’t giving up on challenging the system

For American Farmers:

- Stop waiting for markets to fix themselves—1,420 farms closing annually proves they won’t

- Organize politically at the state levels—300-400 farms can swing rural elections if you vote together

- Explore direct sales aggressively—it’s your only real leverage against processor dominance

- Demand actual DMC reform—the current formula, ignoring labor, fuel, and equipment costs, is insulting

- Consider regional cooperative alternatives to vertically integrated giants—smaller can mean more accountable

- Study Quebec’s political discipline—they didn’t ask nicely, they demanded protection and got it

For Both:

- Accept that all dairy is subsidized—fight about subsidy effectiveness, not existence

- Address succession planning now—both systems struggle with generational transfer

- Build political coalitions beyond ag—rural community survival depends on viable farms

- Learn from international models—New Zealand, EU systems offer valuable lessons

The Bottom Line: Learning from Both Models

What I’ve come to realize is that neither system offers a perfect solution. Canada protects existing farmers brilliantly, but basically locks out newcomers through those quota costs. America keeps the door open but provides zero meaningful protection against volatility that’s destroying multi-generational operations.

There’s potentially a “third way” that combines the best of both—cost-of-production pricing principles from Canada with leased production rights instead of owned quota, maintaining American accessibility while providing stability through collective bargaining frameworks. Something that would include transparent cost-of-production pricing that captures all real expenses (not just three feed ingredients), leased production rights to avoid multi-million-dollar barriers, democratic farmer governance through marketing boards with actual legal authority, market upside participation so farmers benefit from rallies, and real new-entrant programs offering viable scale, not token positions.

Looking at that October 30 CDC announcement giving Canadian farmers a guaranteed increase while American producers face continued uncertainty—it’s not just about prices. It’s showing us that dairy policy is a choice. Both countries are making choices, and increasingly, farmers in both systems are questioning whether those choices actually serve their interests.

That Wisconsin farmer’s observation keeps echoing in my mind: “We keep being told markets will sort it out. But after losing 400 farms in our state last year, I’m starting to wonder if the market’s solution is just to sort us out of business.”

The systems are different, the challenges are real, but the goal should be the same: dairy farms that can survive, thrive, and transfer to the next generation. Right now, neither country has fully figured that out. But understanding what works and what doesn’t in both systems? That’s the first step toward finding something better.

And maybe—just maybe—if we stop defending our respective systems long enough to learn from each other, we might find that third way that actually keeps farmers farming for generations to come.

Learn More:

- Dairy Farm Succession Planning – Critical Conversations for a Smooth Transition – This article provides a tactical roadmap for navigating the complex family and financial conversations essential for a successful farm transition, helping ensure the operation’s legacy and long-term viability—a critical issue raised in the main analysis.

- Navigating the Waters: Key Global Dairy Market Trends for 2025 – This analysis delivers strategic insights into the global economic and consumer trends shaping North American milk prices. It provides essential context for understanding market volatility and making informed, long-range business decisions beyond domestic policy debates.

- The ROI of Robotics: A Producer’s Guide to Dairy Automation – This guide offers a data-driven framework for evaluating the return on investment of dairy automation. It demonstrates how robotics can directly combat rising labor costs and improve operational efficiency, offering a practical solution to the economic pressures detailed above.