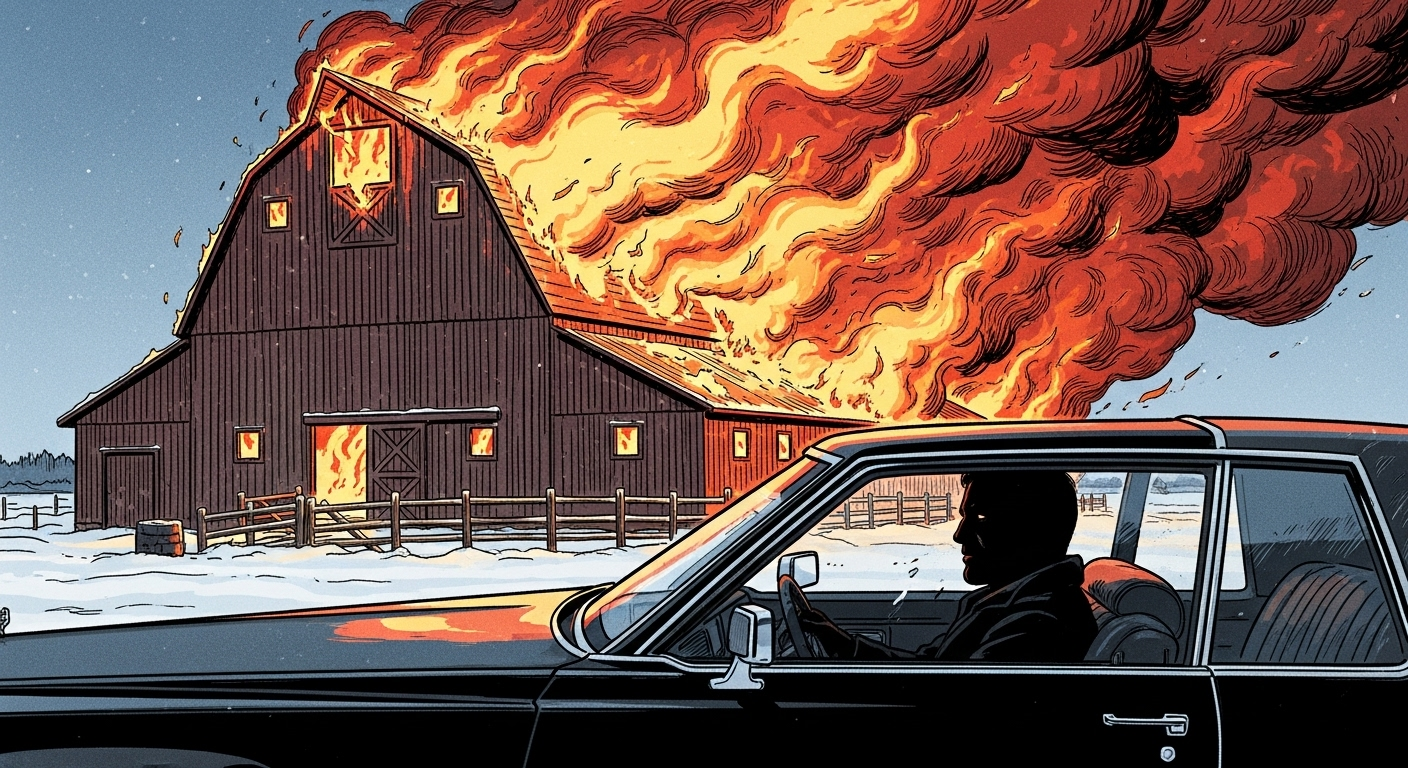

The barn doors were locked from inside. 60 cattle burned alive. And Gordon Atkinson just sat in his Cadillac watching his fraud unfold.

You know that sick feeling in your gut when you drive past a neighbor’s place and something is just… wrong? That’s what happened to one of Gordon Atkinson’s neighbors on February 27, 1981—one of those brutal Ontario winter mornings where the cold cuts right through your coveralls and you can barely feel your fingers.

A neighbor was flashing his headlights, trying to flag down Gordon as he headed north on that county road about a mile and a half from his rented barn. When he pulled alongside, the neighbor shouted, “Look behind you—I think that’s your barn on fire!”

Gordon’s response should’ve been the first red flag. “Can’t be. I’ve just come from there.”

But when he turned that Cadillac around, the ugly story truly began.

According to E.Y. Morwick’s detailed account in his livestock records, the flames were shooting up like angry fingers against that February sky, smoke billowing black and thick enough to taste. You could smell it for miles—that god-awful stench of burning flesh that any livestock producer knows means animals are dying. Sixty head of cattle were trapped inside, bawling in absolute terror while neighbors stood helpless in the snow, hands jammed deep in their pockets.

Here’s what still gives me the chills after all these years: those barn doors were locked from the inside.

Gordon Atkinson never got out of his car. Just sat there watching his cattle burn to death. When someone asked him about it later, Morwick records his response as bone-chilling: “According to Gord, it was no big deal. The calves were insured, after all, for $50,000 apiece.”

That reaction should’ve been everyone’s wake-up call. But this was the height of the Holstein boom—when million-dollar cattle sales were making headlines and everyone was drunk on genetic dreams. What we didn’t realize then was that we were watching the beginning of one of the most devastating agricultural fraud schemes in Canadian history.

The Golden Years That Bred a Monster

To understand how Gordon Atkinson became the cautionary tale he is today, you need to understand the world he entered. The 1970s and early ’80s were… well, they were intoxicating times in our business. And I mean that literally—the whole industry was high on its own success.

This wasn’t just farming anymore. This was theater, high-stakes theater played out in auction barns where the air hung thick with sawdust and tension, where the rapid-fire chatter of auctioneers mixed with the rustle of sale catalogs and the scratch of pens recording bids that would make your land payments look like pocket change.

The foundation for all this craziness had been building since Michael Cook first brought Holstein-Friesian cattle to Ontario back in 1881. But by the ’70s, something fundamental had shifted.

The focus moved from the milk tank to the marketing budget. From 4 AM milking routines to show-ring prestige. Operations like Romandale Farms—you remember Stephen Roman, the uranium guy—they turned cattle sales into major events. Dave Houck, Roman’s superintendent, was brilliant at it. Their nineteen production sales systematically raised the bar, creating this culture where the price you paid for a cow mattered dramatically more than the milk she’d produce.

The numbers from that era are still staggering. Hanover Hill Holsteins’ 1972 dispersal grossed over $1.1 million for 286 head. Just one cow family—Johns Lucky Barb and her progeny—brought $350,500. These weren’t transactions; they were declarations of war, fought with checkbooks instead of common sense.

What’s really interesting here is how the tax codes were fueling this whole thing. Section 46 of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code, for example, created a massive tax shelter for wealthy investors. Non-agricultural money was pouring into the North American Holstein market like water through a burst dam. Wealthy guys were offsetting livestock costs against personal income, creating artificial demand that sent prices into orbit.

But here’s the thing that strikes me about that whole period—underneath all the speculation, there was real genetic progress happening. Milk production per cow was genuinely improving through better breeding, management, and nutrition. That gave legitimacy to what was becoming increasingly detached from reality at the top end.

When you’re dealing with that much money and that much ego, it creates pressure. And pressure has a way of revealing what people are really made of.

The Mystery Man with Deep Pockets

What made Gordon so fascinating—and ultimately so dangerous—was how he seemed to materialize out of thin air with unlimited cash. In our business, where everyone knows everyone and family histories go back generations, Atkinson was this enigma in expensive suits, driving luxury cars to cattle auctions and writing checks that made seasoned veterans nervous.

His buying pattern wasn’t typical herd building. It was performance art, each purchase louder than the last. In 1968, he outbid everyone at the Brubacher 300 Sale to claim Seiling Perseus Anna for $37,500. Two years later, he set a record paying $40,000 for her daughter, Heritage Rockanne, at the Orton Eby dispersal—and this was after outbidding Stephen Roman himself.

Get this—on the same day, he casually added Brubacher Supreme Penny for $23,000 and Seiling Adjuster Pet for $15,500. The man was buying cattle like most of us buy feed. He just kept writing checks.

The coffee shop talk about his money was constant. Some said he’d inherited from a bachelor uncle. Others figured he’d made a killing in Toronto real estate during the city’s boom. Still others thought he was leveraged to the hilt with the banks.

What bothered people, according to Morwick, was that he bought cattle “regardless of their profitability.” That’s not how dairy farmers think, you know? We’re always calculating feed costs, breeding programs, and milk premiums. But Gordon was buying prestige, not production potential.

At the Lingwood Dispersal in 1973, he paid $50,000 for Llewxam Nettie Piebe A. In 1979, at the Romandale Dispersal that drew buyers from around the world, he paid $66,000 for Romandale Telstar Brenda—and this was after her son had just sold for a world-record $400,000.

The problem with building your reputation on image alone is that image is hungry. It always needs feeding. Each spectacular purchase raised the bar for the next one. What looked like confidence from the outside was actually a trap—a financial treadmill that would eventually demand payment in ways nobody imagined.

From what I’m seeing on farms today, that same pressure still exists. Maybe not at the Atkinson level, but it’s there… the temptation to chase the next big genetic investment, the next show-ring star, the next social media sensation. The tools have changed, but the fundamental psychology remains exactly the same.

When Success Became Suspicious

By the early ’80s, the economics were catching up with Gordon’s spending habits. Even the most expensive cattle weren’t generating the returns needed to justify their purchase prices. That’s when the “accidents” started happening.

Seiling Perseus Anna, his $37,500 foundation cow, was supposed to be the cornerstone of his genetic program. Instead, she became the first victim in what would become a disturbing pattern. During what should have been a routine embryo flush at ViaPax—you know, the technology that lets elite cows produce dozens of offspring—Anna had a “mysterious” fall and had to be destroyed.

The Holstein community is tight-knit. Word travels fast, and Anna’s death raised eyebrows throughout the industry. But Gordon’s response was characteristically cold: she was heavily insured.

Then came that February fire I mentioned earlier. Sixty head dead, including those fifteen Citation R. sons that Gordon had been promoting as “maternal brothers” of a $400,000 bull. The animals were insured for $3 million. Three million dollars. Let that sink in for a minute.

What really bothered the neighbors: two years later, lightning struck twice. Another fire, more dead cattle, another insurance claim. In any other business, you might chalk it up to bad luck. But in the pressure-cooker world of elite Holstein breeding, where every animal is catalogued, valued, and watched, two major fires at the same operation within two years? That’s when whispers started.

The mysterious deaths weren’t limited to the fires. Farlows Valiant Rosie, the cow Gordon bought after she was voted All-American 4-year-old in 1984, was supposed to be his show string star for 1985. She started out right, topping her class at the Ontario Spring Show, but at the Royal, she slipped to Honourable Mention, which didn’t help her value.

Before long, she died of “mysterious causes.” Once again, the insurance company wrote a check that more than covered Gordon’s investment.

What struck me about these incidents was their timing. Each death seemed to happen just when an animal was failing to live up to its expensive price tag. Gordon had discovered something that would prove irresistible to his increasingly desperate situation: dead cows were often worth more than living ones.

The same pressures that drove Gordon to those desperate measures… they haven’t gone away. When you’ve got a genomic star that isn’t living up to the hype, when you’ve invested heavily in an animal that’s not performing, when the social media buzz dies down and you’re left with the harsh reality of production records… that’s when character gets tested.

The Paper Trail That Built a Criminal Empire

Gordon’s scheme gets really sophisticated here, and honestly, it’s something every producer should understand because the vulnerabilities he exploited… well, they still exist today in different forms.

The string of fires and suspicious deaths were just the setup for the main event: a multi-million dollar insurance fraud that exploited the very system designed to protect against it. Think about how livestock insurance works—companies don’t employ Holstein experts; they rely on accredited appraisers to determine the value of deceased animals.

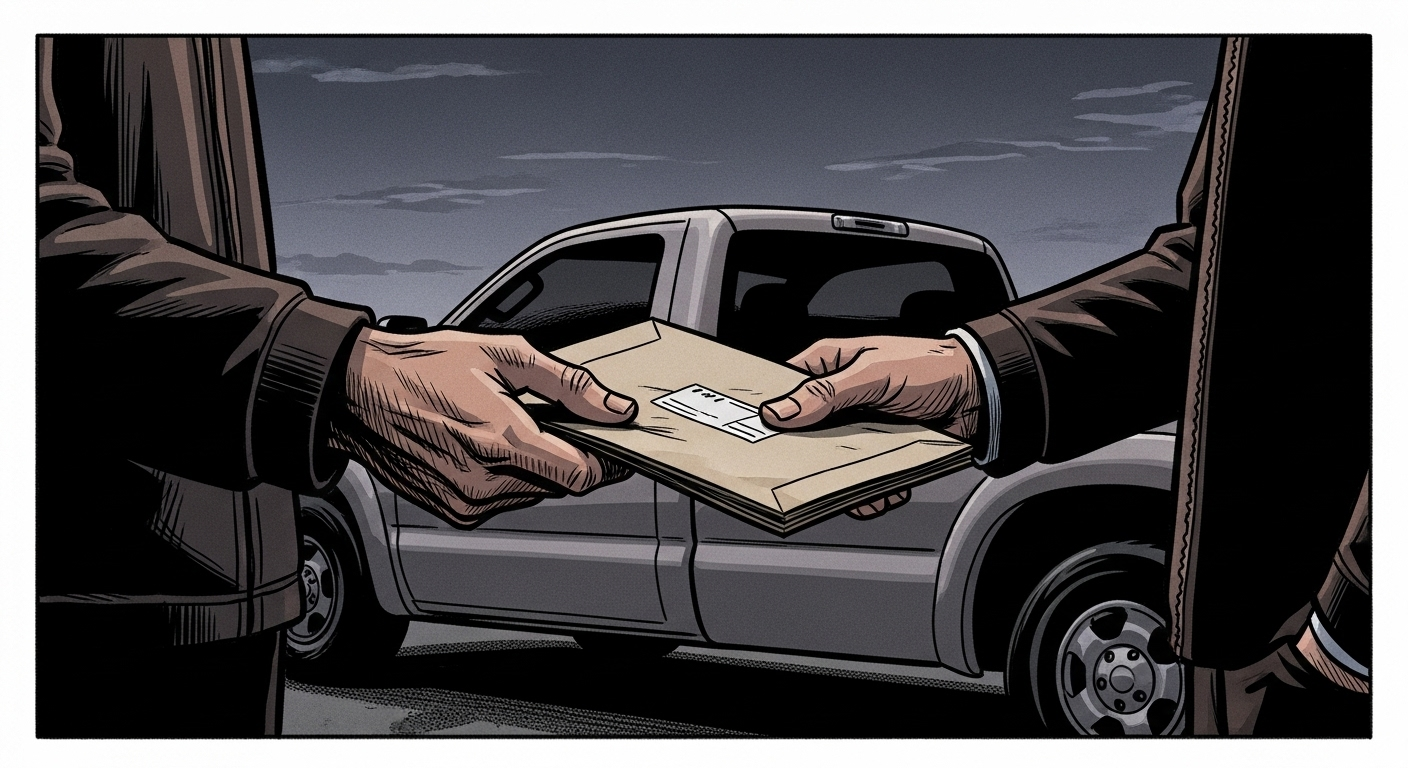

All Gordon needed was to find someone willing to sell their professional integrity.

He found that person in Vernon Butchers, an appraiser from Acton who owned All-Star Holsteins. These guys had known each other practically all their lives, had even partnered in cattle. One of the animals they owned together was Killdee Elevation Edie, the All-American 5-year-old of 1983.

The corruption was breathtakingly direct.

When Royal Insurance demanded proof of value for the cattle lost in that first fire, Gordon’s proposition was blunt: “Give me the values I want, in line with what the cattle were insured for, and I’ll look after you.”

When Butchers asked how he’d be “looked after,” Gordon’s response was clinical: “Fifty thousand dollars today and another fifty when I get the insurance money.”

For a promised $100,000, Vernon Butchers agreed to provide the fraudulent appraisals Gordon needed. With those inflated valuations in hand, Gordon submitted his claims. The insurance company, armed with what appeared to be legitimate expert testimony, cut a single check for over two million dollars.

That’s not just fraud—that’s turning the entire system inside out, using the industry’s own trust mechanisms as weapons against itself.

Here’s the scary parallel: Gordon Atkinson needed a corrupt appraiser to inflate value on paper; today, an algorithm with a limited data set can do the same thing with a single genomic report. When genomic companies can inflate expected breeding values based on limited data, when social media can create artificial demand for cattle that haven’t proven themselves in the barn… we’re dealing with the same fundamental vulnerabilities Gordon exploited.

The Wire That Brought Down Everything

The Royal Insurance Company’s patience finally ran out. Faced with mounting losses that defied all statistical probability, they moved beyond claims processing to active investigation. That’s when they contacted the Ontario Provincial Police, and the OPP’s Anti-Rackets Squad took over.

The police used a classic technique: a court-authorized wiretap. To test their suspicions, they orchestrated a sting operation with devastating effectiveness. A Wisconsin breeder, cooperating with authorities, called Gordon with a pointed question: how do you kill an insured cow to collect the money?

In a moment of stunning arrogance, Gordon walked directly into the trap. According to Morwick’s account, his advice was chilling: “It’s easy. Use Succinylcholine. Inject it under her tail. Nothing to it.”

Those words, captured on tape, were more than just instructions—they were a confession to criminal knowledge and intent. But the most devastating blow came from within his own family.

His son John, who’d served as herdsman at Meadolake, finally reached his breaking point. For years, John had turned a blind eye to increasingly suspicious activities. There was even the night he told his wife he was going out with the boys—not for pleasure, but because he suspected his father and brother George were “up to something” and he needed an alibi. The next morning, Gordon’s new Cadillac was found torched in a bad part of London.

In September 1986, when John was asked to sign an insurance claim for Farlows Valiant Rosie, he refused. “I won’t do it,” he told his father. Gordon’s response revealed how completely the criminal enterprise had consumed him: “You’ll do it or get the hell out.”

That day, John contacted the OPP anti-rackets squad and agreed to cooperate. The family’s reaction was swift and violent. George tried to run John down with his car. Then one night, Gordon appeared at John’s home while his daughter-in-law was alone with her two young sons. His message was delivered with chilling precision: “Keep talking to the police and I’ll poison your kids. And I know how to do it.”

“It was a hell of a note. Father turning on son, brother on brother. Right out of the Bible.”

— Barrie neighbor

When the Gavel Falls

The exposure of the fraud led to total collapse. Gordon and his son George were charged with fraud related to obtaining $12 million through various schemes, making it one of the largest agricultural fraud cases in Canadian history. The charges were documented in Information #0710-87-03388.

Interestingly, despite the suspicious pattern of fires, the charges focused on fraud rather than arson. Prosecutors understood that proving insurance fraud would be easier than establishing arson beyond a reasonable doubt, especially with recordings of Gordon explaining exactly how to kill insured livestock.

The sentence was controversial. Despite the massive scale of their crimes, the Atkinsons negotiated a plea deal that allowed them to avoid prison time. They received suspended sentences with probation orders requiring restitution. Many felt the punishment didn’t match the magnitude of their deception.

But the criminal case was only one front in their legal battles. The Royal Insurance Company filed a civil lawsuit seeking $5 million in damages. Overwhelmed by court-ordered restitution and massive civil claims, the Atkinsons declared bankruptcy.

The bank seized everything—Meadolake Farm itself and the entire herd that had been both the foundation of their rise and the instrument of their downfall.

The Final Humiliation

The ultimate symbol of Gordon’s fall played out at Brubacher’s—the same auction house where he’d once made his reputation with record-setting purchases. The bank-ordered dispersal sale was the complete reversal of fortune, a public stripping away of the illusions that had sustained his empire.

The cattle that had once commanded astronomical prices based on fraudulent appraisals now faced the harsh judgment of the open market. According to Morwick’s account, they sold for “mere peanuts”—a devastating market correction that exposed the hollow foundation of Gordon’s entire enterprise.

Perhaps most poignantly, Gordon attended the sale, watching his life’s work dismantled lot by lot. When he thought a cow was selling too cheaply, he’d rise from his seat, wave his arms, and urge the crowd to bid higher. The spectators laughed. “Why’s he doing that?” they asked. “The cows belong to the bank, not to him.”

Shortly after this final humiliation, Gordon Atkinson’s story reached its conclusion. He died of a heart attack at the Toronto home of Mona Cimarone, a woman who’d been his housekeeper during better times. Even in death, controversy followed—when she found his body, she called George, who staged the scene to make it appear Gordon had died in his car at a Toronto hospital.

The Ghost of Meadolake: A Legacy for Today’s Industry

The Gordon Atkinson case isn’t just a historical curiosity—it’s a mirror reflecting vulnerabilities that still exist in our industry today, maybe even more so.

What strikes me about this case is how it exploits the very foundations of agricultural business: trust, reputation, and the often-intangible value of genetics. Look at what’s happening in our industry right now. We’re seeing animal valuations that would make those 1970s prices look conservative. When I see genetic companies pushing astronomical valuations based on genomic predictions with limited daughter proof, I think about Gordon’s fraudulent appraisals.

Genomics has created new opportunities for the same kind of manipulation. When a bull’s genomic evaluation can fluctuate wildly based on daughter data… when genetic defects can be hidden until after expensive matings are made… when marketing can create artificial demand divorced from actual genetic merit… we’re right back in Gordon Atkinson territory.

From what I’m seeing on farms across Ontario—and talking to colleagues in other regions and countries—social media is amplifying marketing messages in ways that make traditional promotion look quaint. When I watch influencers promoting cattle with little regard for actual performance data, I remember how Gordon bought cattle “regardless of their profitability.”

The scary part? Today’s technology makes fraud both easier to commit and harder to detect. Digital records can be manipulated. Genomic data can be cherry-picked. Social media can create artificial demand faster than traditional marketing ever could.

The same speculative culture that enabled Gordon’s crimes is still with us. We’re still measuring success by sale prices rather than sustainable profitability. We’re still more impressed by marketing than by long-term performance records.

Young farmers, especially, are vulnerable to the same kind of thinking that drove Gordon Atkinson—that spectacular purchases and high-profile acquisitions are the path to respect and success in our industry. When I see operations leveraging their entire future on genetic investments that exist more on paper than in the barn… when I watch farmers mortgaging everything to chase the latest genomic trend… that’s when I think about Meadolake.

Edward Young Morwick, the Holstein historian who documented this case, captured the essential lesson perfectly:

“In the high-pressure world of show cattle, ego always gets ahead of responsibility.”

Gordon Atkinson’s career was the embodiment of this maxim. For today’s dairy producers, this story serves as a powerful reminder that the most valuable asset in our business isn’t a champion cow or a record-setting bull—it’s integrity.

The complete collapse of value seen in Meadolake’s final dispersal sale, where cattle once valued in the millions sold for “peanuts,” stands as an enduring symbol of what happens when reputation is built on deception rather than genuine achievement.

The Atkinson case belongs to a grim fraternity of agricultural crimes that continue to plague our industry. The pattern remains consistent: where there are high-value, transportable assets like pedigree livestock, there will always be those willing to exploit trust for criminal gain.

What’s happening across the industry today is that we’re creating new vulnerabilities while the old ones persist. The pressures that created Gordon Atkinson are still with us, just in different forms. In an industry where reputation spans generations and trust forms the foundation of every transaction, those who choose the path Gordon walked don’t just risk their own destruction—they threaten the very values that make our dairy community strong.

What we can learn from Gordon’s downfall is that the most dangerous moment comes when the pressure to maintain an image becomes stronger than the commitment to honest business practices. In our industry, where reputation spans generations, that’s a lesson we can’t afford to forget.

The legacy of Meadolake Farm isn’t found in the ashes of burned barns or the fraudulent appraisals that once inflated paper values. It lives in the permanent lesson that authentic success in agriculture must be built on substance rather than spectacle, integrity rather than image, and responsibility rather than ego.

That’s a lesson as relevant today as it was forty years ago… maybe more so, given the new technologies and pressures we’re dealing with. The “Black Days at Meadolake” stand as a testament to what happens when we lose sight of what really matters in this business we all love.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.