Beef-on-dairy doubled your calf checks. It also drained 800,000 heifers from the U.S. pipeline. Here’s how to keep winning without wrecking your 2027 herd.

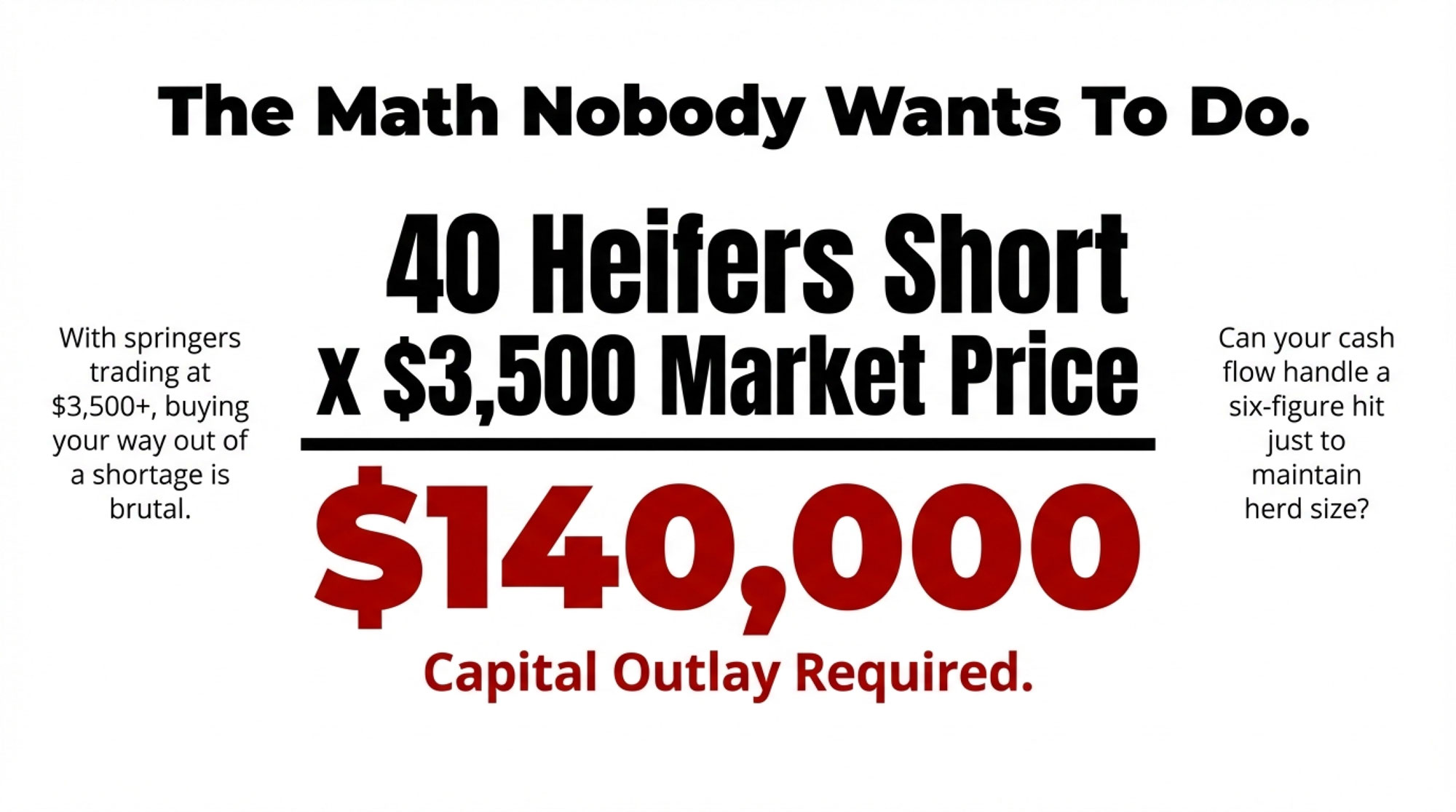

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Beef-on-dairy has been a lifeline—$650 calves three years ago now bring $1,400, and those checks have kept plenty of operations in the black. But there’s a cost building in the background. U.S. heifer inventories just hit a 20-year low, CoBank projects an 800,000-head gap by 2027, and $10 billion in new processing plants are coming online hungry for milk and butterfat. The math nobody wants to do: every breeding decision today locks in your replacement options two years out. Herds running 35-40% beef semen without a clear pipeline picture could face $3,500+ springer bills when the shortage really bites. The good news is that a simple 24-month dashboard can help you keep cashing beef checks without building a hole you can’t fill come 2027.

You know that feeling when you open the calf check from your buyer and think, “Wait, this can’t be right”? A lot of us have had that moment over the last few years. What used to be a drag on cash flow—those plain Holstein bull calves nobody wanted—has turned into serious money when you cross the right cows with beef sires.

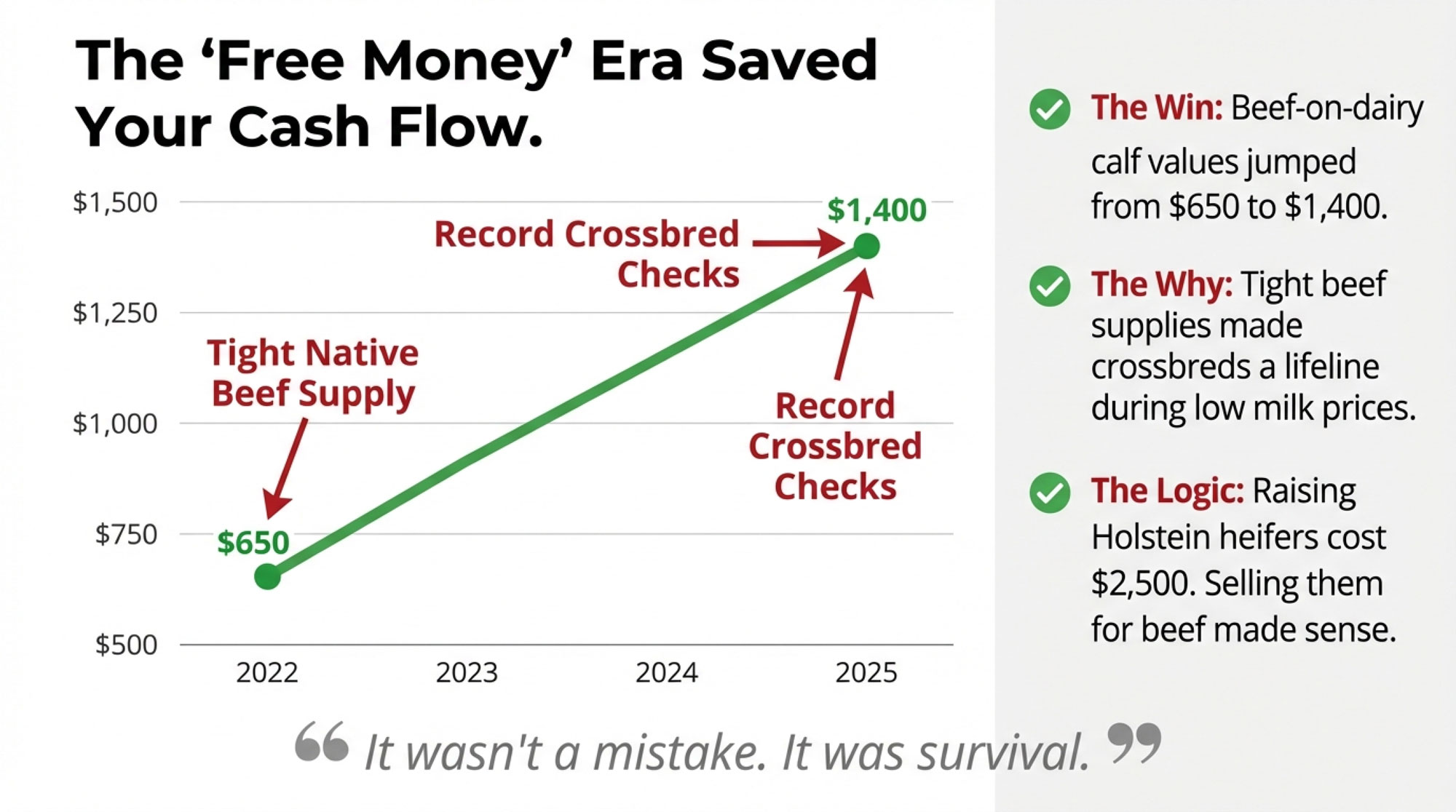

And the numbers back it up. Average day‑old beef‑on‑dairy calves have climbed from roughly 650 dollars to around 1,400 dollars over the last few years, depending on your region and calf weights. Dairy‑beef cross calves keep breaking records at sales—often bringing 1,000–1,500 dollars per head in strong markets.

So that’s the good news. Here’s where it gets more complicated.

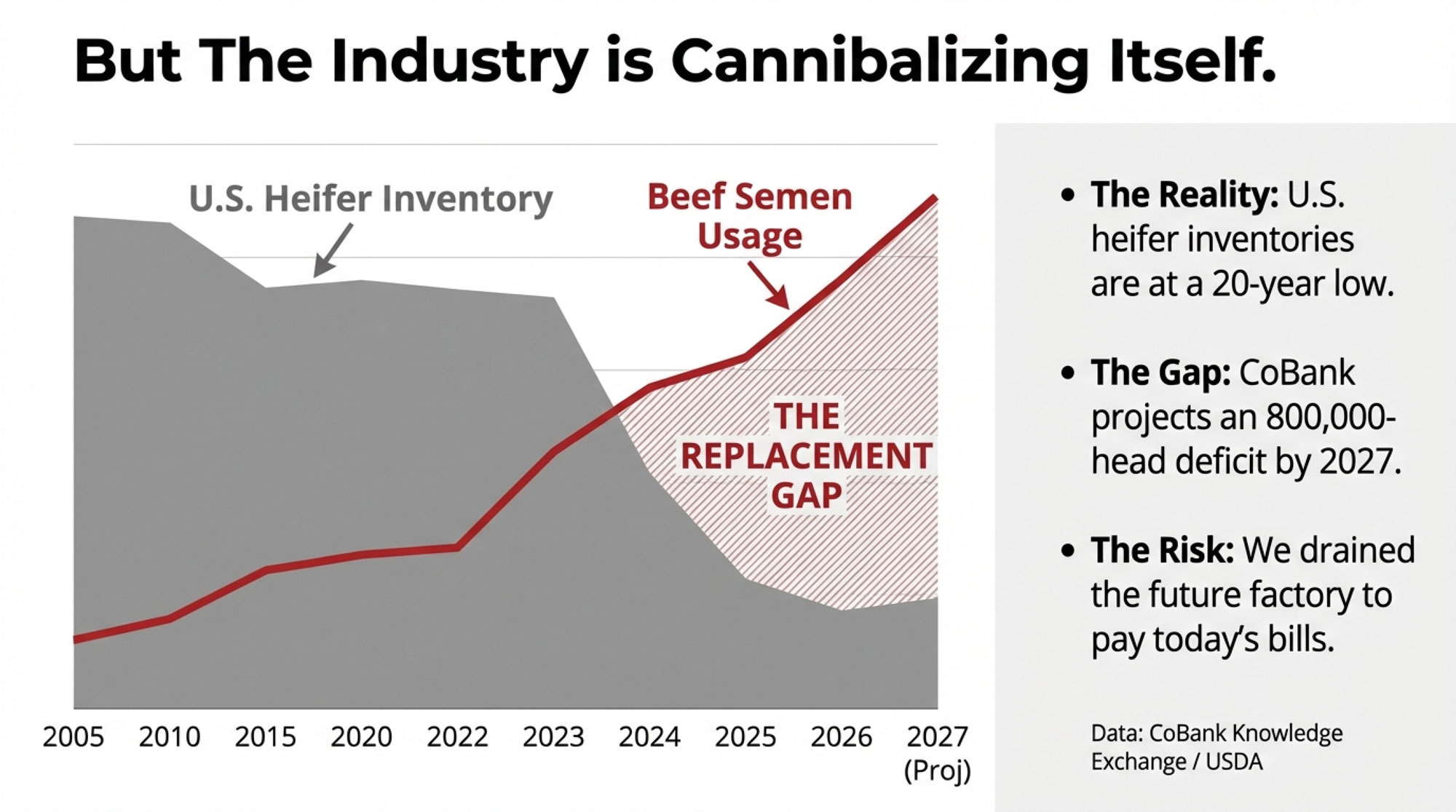

A 2025 CoBank Knowledge Exchange report flagged something that should get our attention: U.S. dairy heifer inventories have dropped to a 20‑year low, and they’re projected to shrink by about 800,000 head before starting to recover in 2027. That’s not a small number. And on top of that, Rabobank analysis shows Brazil overtook the U.S. as the world’s top beef producer in 2025—roughly 12.5 million metric tons versus 11.8 million for us.

| Year | 0–3mo | 3–6mo | 6–12mo | 12–18mo | 18–24mo | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 4.60 |

| 2024 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 1.05 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 4.42 |

| 2025 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 4.21 |

| 2027E | 0.80 | 0.77 | 1.02 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 4.40 |

What does that mean for your operation? Well, in practical terms, many of us aren’t just selling milk with some cull cows on the side anymore. We’re running dual‑market protein businesses—milk plus cattle—and how those two sides interact over the next 24 months will have a lot to say about herd stability, fresh cow management, butterfat performance, and honestly… who’s still milking come 2030.

Here’s what’s encouraging, though: you don’t have to abandon beef‑on‑dairy to protect your future herd. But you probably do need to think differently about time, replacements, and risk.

How Beef‑on‑Dairy Got So Big, So Fast

Looking back just a few years, the shift toward beef semen on dairy cows made a lot of sense. The economics lined up almost too well.

Why Those Beef Calf Checks Took Off

A few big forces hit at the same time:

- Native beef supplies got tight. USDA’s 2024 cattle inventory report showed the U.S. beef cow herd at its smallest level since the early 1960s, years of drought‑driven liquidation finally catching up. By 2025, U.S. beef output had declined to approximately 11.8 million tons, according to Rabobank figures.

- Brazil stepped on the gas. They expanded feedlot capacity, improved genetics, and increased carcass weights. Rabobank estimates Brazilian beef production hit roughly 12.5 million tons in 2025, nudging past the U.S. and easing the global squeeze a bit.

- Beef‑on‑dairy premiums exploded. As packers and feeders got comfortable with crossbred performance, prices followed. Calves that averaged around 650 dollars three years ago were commonly selling near 1,400 dollars by 2025. Dairy‑beef crosses repeatedly setting highs, often more than doubling what straight Holstein bulls once brought.

- Raising every heifer stopped penciling. You probably know this already, but economic analyses from land‑grant universities and journals like Journal of Dairy Science consistently show it costs 2,000–2,500 dollars in direct costs to raise a heifer from birth to calving once you factor in feed, housing, labor, and health. When you could buy Holstein springers for less than that for several years running… well, it made sense to sell more calves for beef.

And the genetics side backs this up, too. A 2022 board‑invited review in Translational Animal Science found that beef × dairy crossbreds—when sires are chosen correctly—can deliver better average daily gain, feed conversion, and carcass weights than straight Holsteins. A companion carcass perspective analysis, also in Translational Animal Science, showed that these crosses can capture real carcass premiums through good marbling and red meat yield when genetic and management decisions align.

So when you put it all together—tight native beef, strong calf prices, underpriced Holstein heifers, better beef × dairy genetics—it’s no surprise so many herds leaned into beef‑on‑dairy. The behavior made sense at the time.

But Here’s the Other Side of That Ledger

On the replacement side, the picture looks very different.

That CoBank report from August 2025 spells it out pretty clearly:

- The number of dairy heifers expected to calve into the U.S. herd has dropped to a two‑decade low.

- Based on their modeling, heifer inventories will shrink by roughly another 800,000 head over the next two years before starting to rebound—assuming breeding patterns adjust.

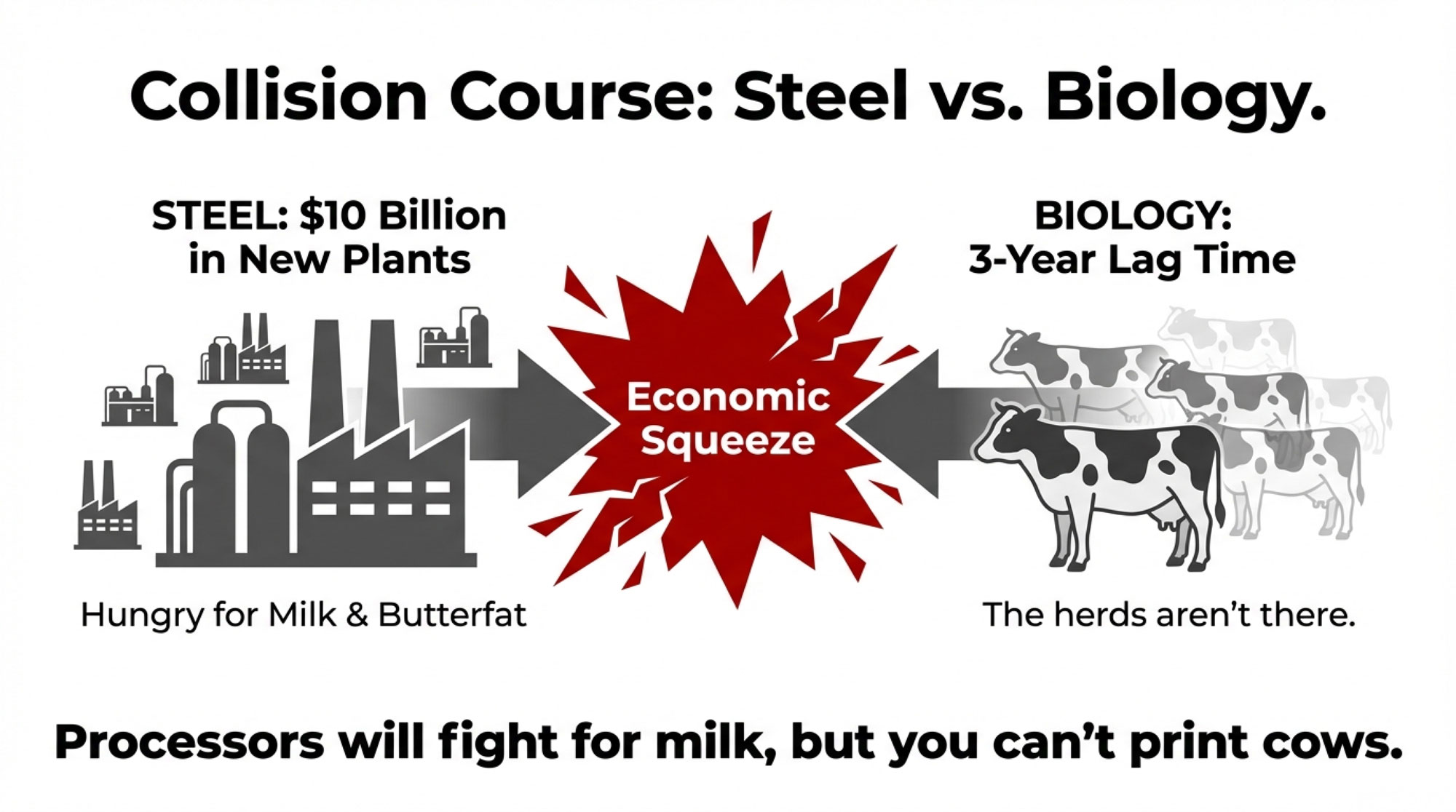

- At the same time, we’re in the middle of an historic 10‑billion‑dollar wave of dairy processing investment. New plants coming online through 2027, all of which will need more milk—and in many cases, more butterfat and protein—once they’re fully running. While plants are being built, the industry is cannibalizing the very ‘units of production’ (heifers) needed to fill them. It’s a collision course between steel and biology.

| Metric | Current State (2025) | Projected Need (2027) | Heifer Pipeline Support | Gap / Risk |

| U.S. Dairy Herd | 9.4M cows | 9.5M–9.7M cows | 800,000 fewer heifers available | SHORTAGE: –2.5M gal/day by 2028 |

| New Processing Capacity | — | $10B invested | Assumes +2–3M gal/day milk | Supply assumption unmet |

| Annual Heifer Output Needed | 2.8–3.0M dairy calves | 3.2–3.4M dairy calves | Beef 35–40% of breeding | Deficit: –300K–400K heifers/yr |

| Heifer Replacement Rate | 28–32% average | 32–35% needed | Currently 22–26% net | Culls > freshening. Herd flat. |

| Heifer Price Impact | $3,000–$3,500 | $4,000–$5,000 projected | Limited availability | Margin erosion: +$1,000–$1,500 |

CoBank economist Tanner Ehmke put it bluntly: those new plants will require more annual milk and component production, and it’s going to take many more heifer calves in future years to bring the national herd back to where it needs to be. The thing is, It will be tight.

On the ground, what many producers are seeing matches that:

- In 2024–2025, according to classifieds and sale reports, good Holstein and Jersey springers have commonly been listed in the 3,000–3,800‑dollar range, with high‑end animals bringing more where supply is really thin. In parts of the Upper Midwest, springers have been trading $200–400 above the national average in recent sales

- CoBank reminds us that rebuilding the replacement pipeline is a “three‑plus year proposition” from the time you adjust your semen strategy to when that bigger wave of heifers actually freshens.

So right now we’ve got:

- Beef‑on‑dairy calves are generating record checks in many barns.

- Heifers are getting more expensive and, in some areas, genuinely hard to source.

- Global beef supply easing a bit as Brazil grows, but domestic replacement supply staying tight.

That’s the setup most of us are working with.

Three Ways Dairies Are Playing the Dual‑Market Game

Talking with producers and advisors across different regions, you start to see some patterns in how herds are handling beef‑on‑dairy and replacements. These aren’t formal categories—just what I’ve observed.

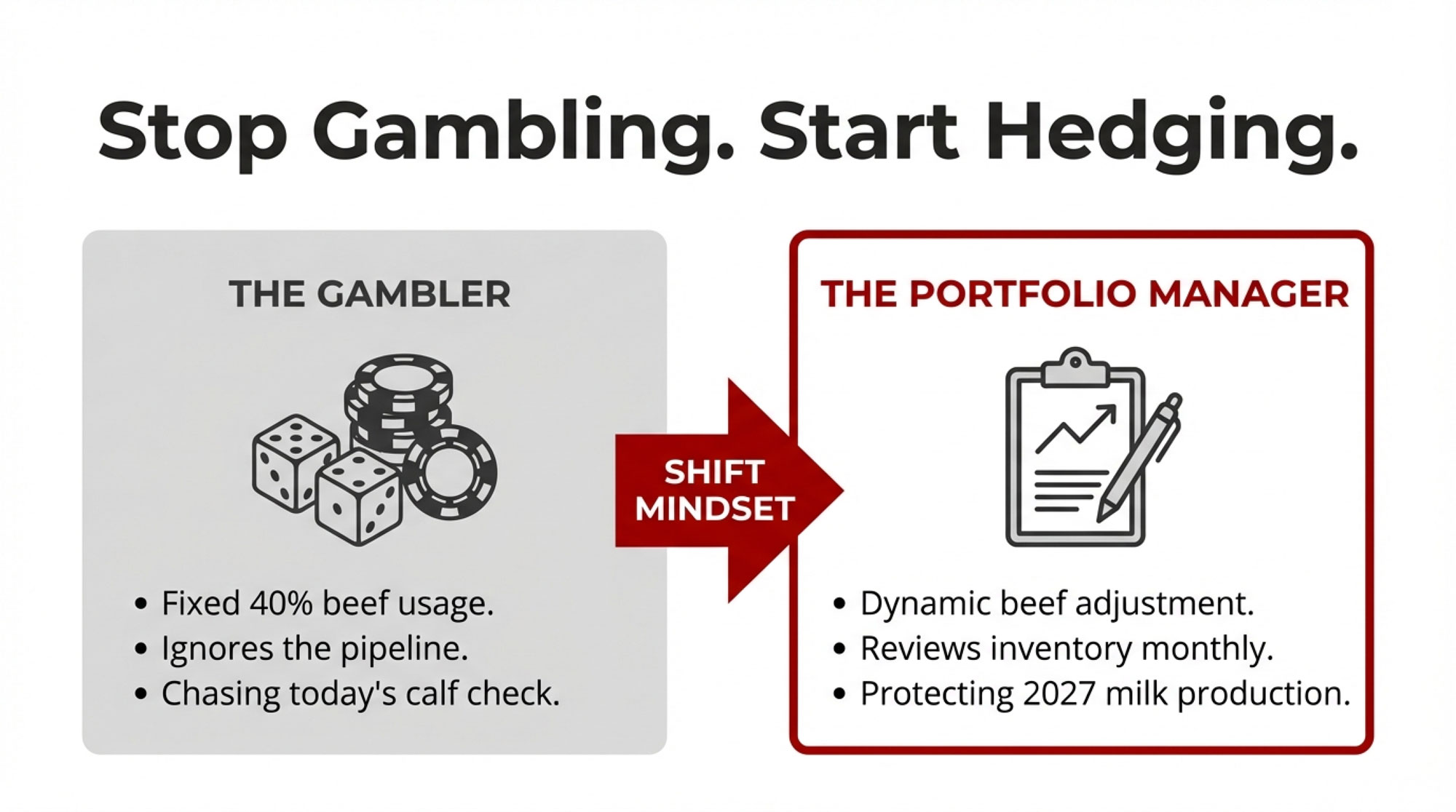

1. The “Set It and Forget It” Approach

Plenty of herds—small, mid‑size, and big—land here:

- At some point, they decided, “We’re a 40% beef herd,” or “We’ll breed 35–50% of cows to beef,” based on the calf checks and semen promotions at the time.

- That percentage doesn’t move much unless something feels really broken—maybe calf prices collapse, or the vet mentions they’re running light on replacements.

- They know roughly how many heifers are in the hutches, but there’s no regular projection of heifer inventory by age group against expected culls over the next 18–24 months.

And look, many of these operations used beef‑on‑dairy to get through some tough milk price years. When milk checks were barely covering feed, beef‑on‑dairy gave them non‑milk income they simply didn’t have before.

The risk is that, because biology runs on a long clock, you can slowly build a replacement deficit without feeling it—right up until you suddenly need 40 more springers than you’ve got coming.

2. The “Portfolio Managers.”

On the other end, there are herds—often 800 cows or more, though not always—that treat milk and cattle as one revenue and risk package.

What that typically looks like:

- Quarterly breeding strategy meetings where they review heifer inventory by age band (0–3, 3–6, 6–12, 12–18, 18–24 months), target replacement rate (usually 28–32%), current beef‑on‑dairy calf prices, and recent heifer values from auctions.

- Dynamic beef percentages. Instead of locking in 40% year‑round, they might run 20–25% when short on heifers and 30–35% when they’ve built a cushion.

- Targeted semen use. Genomic tests to rank cows, then sexed semen for the top group and beef semen for lower‑index or problem cows.

- Some are exploring tools like Livestock Risk Protection (LRP) for feeder cattle or talking to commodity brokers about limited CME feeder cattle futures.

Extension educators note that many larger, more risk‑focused herds use some form of forward pricing or revenue protection for a portion of their milk. A smaller but growing subset are starting to apply similar thinking to cattle revenue.

What you hear from managers in this group isn’t about hitting home runs—it’s about smoothing the ride so they can keep investing steadily in fresh cow management, dry cow facilities, and butterfat performance instead of lurching from crisis to crisis.

3. The Relationship‑Driven Opportunists

There’s also a healthy group—often 250‑ to 1,000‑cow family dairies—that lean less on spreadsheets and more on market relationships and timing.

Their system often looks like:

- A standing weekly call with a trusted calf buyer: “What are you seeing? Are beef‑on‑dairy calves trading up, down, or sideways?”

- Regular touchpoints with a heifer broker or custom grower: “What are folks paying for springers? How many do you have for Q1 next year?”

- Ongoing conversation with their nutritionist about feed markets, including how Brazil’s growing grain exports are shaping costs.

When that three‑way radar starts blinking—calf prices softening, heifer bids climbing, feed markets shifting—they move quickly. Maybe they sell a group of calves a little early, grab springers out of a dispersal, or pull their beef percentage back sharply for a trimester.

The common thread among producers who operate this way? They’re willing to move when conditions change. It’s not about perfection—it’s about responsiveness.

The Two Mechanics That Really Matter

Once you get past the day‑to‑day, two things stand out as the real drivers of future pain or stability: biological lag and unhedged cattle revenue.

Biology Runs on a Two‑Year Clock

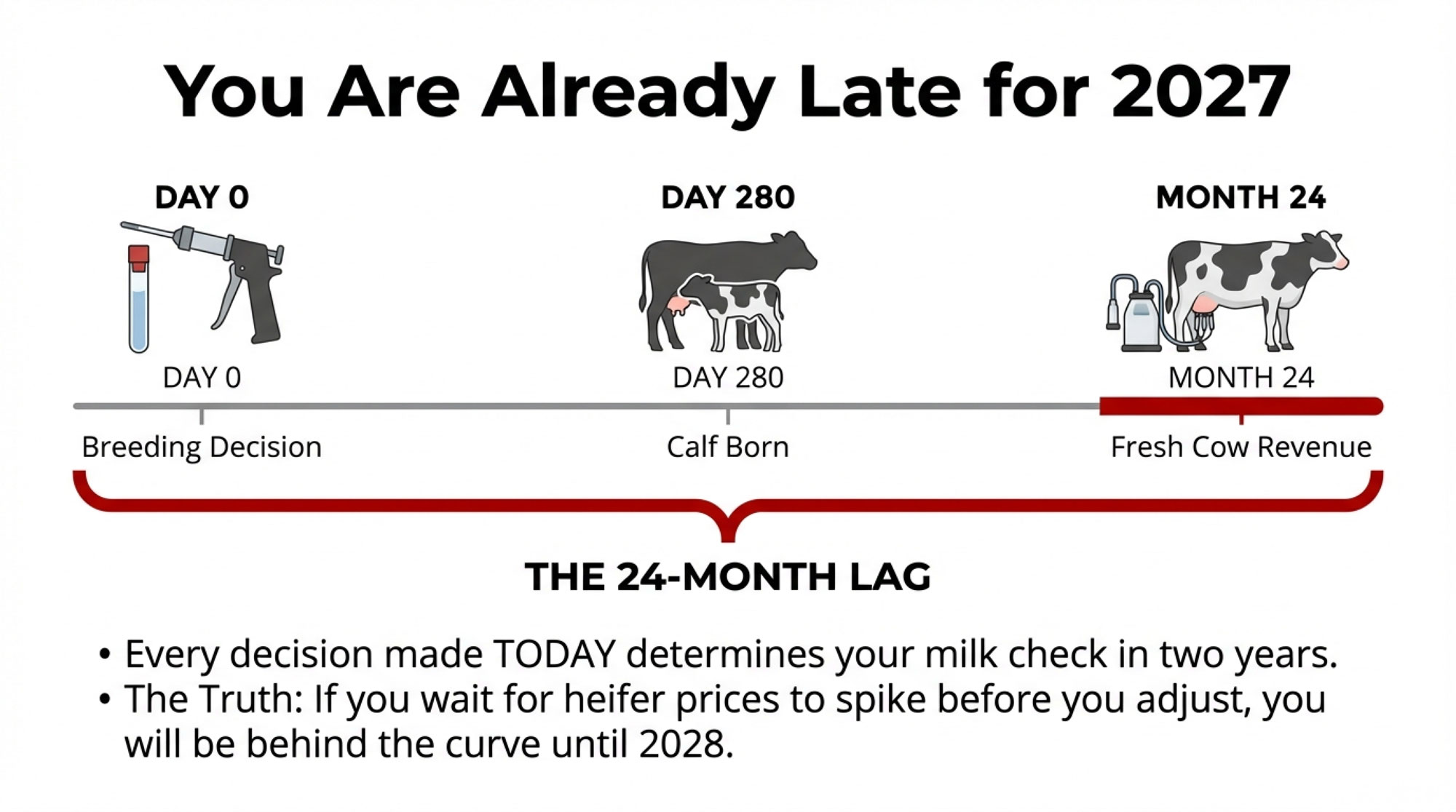

Every breeding decision is really a 24‑month decision, whether we think of it that way or not.

Here’s the rough math:

- Day 0: You breed a cow—beef, conventional dairy, or sexed—based on today’s cash flow and cull list.

- ~280 days later: A calf hits the ground. Beef‑cross bull? That’s a sale within days. Heifer? She heads into the replacement stream.

- ~22–26 months after breeding: That heifer, if she makes it, walks into the parlor as a fresh cow and starts contributing to your milk and component pool.

CoBank and university extension educators have been clear on this: if the industry waits until heifer prices are screaming and auctions are thin to pull back on beef breedings, we’re reacting to a shortage set in motion a couple of years ago. Replenishing that pipeline is a multi‑year project, not a one‑season fix.

So when someone says, “We’ll cut back on beef when we really see heifer prices take off,” what they’re really saying is, “We’ll accept being behind for a couple of years before we start catching up.” That’s not necessarily wrong if you have strong access to outside replacements. But it’s important to see the trade‑off clearly.

Hedging Milk, Letting Cattle Ride

Here’s the other pattern that jumps out: how uneven our risk management has become.

On the milk side, many herds now use Dairy Revenue Protection (DRP) or LGM‑Dairy to cover a portion of their milk, or have forward contracts with their cooperative.

On the cattle side, it’s different. Even though beef‑on‑dairy calves and cull cows can represent a significant share of gross farm revenue—by some industry estimates, 10–15% or more on certain operations—relatively few dairies use formal tools like LRP, CME feeder cattle futures, or structured forward contracts in a consistent way.

And cattle markets still show their usual volatility. 20% price swings over a season aren’t unusual for feeder and live cattle futures.

For a 600‑cow herd, that might mean 250–300 beef‑on‑dairy calves a year at 1,200–1,400 dollars each, plus cull cow checks. Total cattle revenue in the low‑ to mid‑six figures. Leaving that entire stream unprotected while carefully hedging milk is a bit like putting a surge protector on your parlor controls but plugging the compressor straight into the wall.

Nobody needs to become a commodities trader. But it’s worth asking: is there room to set a floor under even 25–40% of that beef revenue, especially when prices look historically high?

From 90‑Day Survival to 24‑Month Planning

At the heart of all this is a basic question:

Are we making breeding and culling decisions based mainly on what we need this quarter, or on what we know we’ll need two years from now?

What 90‑Day Thinking Feels Like

Most of us have been there. Milk prices barely covering costs. Feed isn’t cheap. Loan renewal coming up. And you’re standing in the office thinking:

- Beef semen costs a bit more per straw, but that crossbred calf brings three or four times what a Holstein bull would.

- Raising every possible heifer feels like pouring expensive feed into animals you might not need.

So you push another 5–10 cows into the beef column. Understandable. You’re solving for cash flow.

The tough part is that you’re also chipping away at your 2027 and 2028 replacement pool. Unless you’ve got a clear plan—strong access to custom heifer growers, a standing agreement with a broker, confidence in cross‑border sourcing—those decisions add up.

What 24‑Month Thinking Looks Like

On herds that seem to navigate this with less drama, a few habits show up:

- They know their replacement need. For example: 1,000 cows × 30% replacement rate = 300 heifers/year. About 25 freshening per month just to stay flat.

- They know their pipeline. How many heifers are in each age band? How many are due to freshen each month over the next year?

- They connect that to breeding. Before deciding “35% beef for six months,” they ask, “What does our January 2028 heifer count look like if we do that?”

Once you put those numbers on one page, many decisions become clearer. You might still run 30% beef because your region has decent heifer access. But you’ll be doing it with eyes open.

A Simple Tool: The 24‑Month Replacement Dashboard

So let’s talk about something practical you can do this month that doesn’t require a consultant or fancy software.

| Metric | Current Herd (2025) | Conservative Scenario (25% Beef) | Balanced Scenario (35% Beef) | Aggressive Scenario (45% Beef) | Projected Status (2027) |

| Milking Cows | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | — |

| Annual Replacement Need | 210 (30% cull) | 210 | 210 | 210 | 210 |

| Dairy Breedings (%) / Year | — | 75% | 65% | 55% | — |

| Beef Breedings (%) / Year | — | 25% | 35% | 45% | — |

| Expected Heifer Calves / Year | — | 210–215 | 185–190 | 160–165 | — |

| Projected Heifer Inventory (18–24mo, 2027) | 180–195 | 215–225 | 185–195 | 155–165 (–45 SHORT) | Shortfall cost: $3,500 × 45 = $157,500 |

Think of it as a 24‑month replacement dashboard—a one‑page reality check you update monthly.

What This Usually Includes

- Basic herd math.

- Current milking + dry cows.

- Target replacement rate (26–32%, depending on culling and growth).

- Annual and monthly replacement needs.

- Heifer inventory by age.

- 0–3 months, 3–6 months, 6–12, 12–18, 18–24 months.

- Apply a reasonable pre‑fresh attrition factor—many extension sources use 6–10% based on historical data.

- Projected heifer calf output.

- Monthly dairy breedings with conventional semen × conception rate × ~48% female ratio.

- Monthly dairy breedings with sexed semen × conception rate × 70–90% female ratio (varies by bull and program).

- Beef breedings counted as zero heifers.

- A simple projection.

- For each month over the next 18–24 months, how many heifers are scheduled to freshen?

- Compare that to your replacement needs.

Several land‑grant extension bulletins use similar frameworks for “raise vs. buy” decisions. The key is making the future visible in a way that’s easy to revisit.

How It Changes the Conversation

Once that’s on the wall in your office:

- When your AI tech asks, “How many are we doing beef this month?”, you’re not guessing. You can say, “We’re 40 heifers short 18 months out. Let’s pull beef back a few points and revisit in 30 days.”

- When your lender comes by, you can show them exactly why you’re trimming beef breeding—to avoid an ugly replacement bill in two years. That goes over better than a surprise heifer spending spree later.

- When calf prices spike, you’ve got context. Heifer‑long? Maybe bump beef to capture those checks. Heifer‑short? Resist the urge to chase every dollar.

This tool doesn’t make decisions for you. It just prevents the “I didn’t realize it was that bad” moment that’s put more than a few herds in a bind.

Here’s an example of how this plays out: A herd running around 700 cows might build a simple spreadsheet version and discover they’re on track to be 40–50 heifers short in 20 months. Rather than slamming on the brakes, they trim beef breeding by 5–7 points over two quarters and push more sexed semen on top cows. A year later, they’re almost exactly on target—and they never had to scramble for expensive springers.

Not Everyone Sees the “Crisis” the Same Way

It’s worth noting that not all experts agree on how severe or long‑lasting the replacement squeeze will be.

- CoBank sees a clear, multi‑year shortage keeping a lid on how quickly U.S. milk output can grow, especially as new plants come online.

- Some producers, especially in regions with strong custom heifer grower networks—think parts of Wisconsin, New York, or Quebec—argue that while things are tighter, they’re not in crisis mode. They point to increased sexed‑semen use on top cows, growing interest in contract‑raising, and potential to import replacements when prices justify it (though that brings disease, adaptation, and logistics questions).

There’s also a valid point that some of this shortfall is a correction from years when we over‑raised marginal heifers with little genetic upside. Some industry observers have noted that a chunk of this is the industry finally being more selective—and that’s healthy. The trick is not overshooting the mark.

From a practical standpoint, the takeaway isn’t that you must agree with the most pessimistic forecast. It’s that you probably can’t afford to ignore the possibility that replacements stay tight and expensive while new processing capacity ramps up. A simple dashboard lets you stress‑test your own farm against both scenarios.

Practical Takeaways

So what can you actually do with all this? Here are a few points to chew on.

1. Treat Cattle Checks as Core Business

If beef‑on‑dairy calves plus cull cows bring in a significant share of your revenue, it’s time to:

- Track that income as its own line in your financials.

- Ask about tools like LRP feeder cattle coverage or forward‑price agreements with trusted buyers.

- You don’t have to hedge every animal. Even protecting 25–40% can take a lot of edge off.

2. Make Replacements a Standing Agenda Item

Before setting this year’s beef percentage, take one evening to:

- Write down current cow numbers and a realistic replacement rate.

- Pull the heifer inventory by age group.

- Sketch a rough 18–24 month projection.

Then ask directly: “If we keep breeding 40% beef, do we have a plan—and capital—to buy the heifers we’ll be short?”

3. Adjust in Steps, Not Swings

If you’re on track to be 50 heifers short two years out, you don’t have to yank the wheel:

- Drop beef breedings by 3–5 points this trimester.

- Shift more sexed semen onto your best genomic cows.

- Re‑evaluate quarterly.

Gradual change is usually more realistic and easier on cash flow than dramatic one‑time shifts.

4. Bring Your Lender In Early

Most farm credit officers are reading CoBank and our own analysis—they know the heifer story. What they don’t always know is how you’re thinking about it.

Show them a simple replacement projection and a modest rebalancing plan. You’re more likely to get support for small proactive adjustments than for emergency financing later.

5. Respect Regional Realities

What makes sense on a 3,000‑cow dry lot in western Kansas isn’t identical to a 300‑cow tie‑stall in eastern Ontario or a 1,200‑cow free‑stall in Wisconsin.

- In some western regions, access to custom heifer raisers changes the calculus.

- In parts of the Northeast and the Upper Midwest, strong local demand can push heifer prices above the national average.

- In quota systems like Quebec or Ontario, butterfat incentives may tilt decisions toward maximizing fresh cow performance rather than just head count.

The point isn’t to copy your neighbor’s beef percentage. It’s to understand how your replacement pipeline, local markets, and processor signals fit together.

Managing the Whole Game

What’s become clear is that beef‑on‑dairy is here to stay. Peer‑reviewed work in Translational Animal Science and Journal of Dairy Science confirms what the market already knew: beef × dairy calves are now a recognized, important part of the North American beef supply chain.

That’s good news. There’s real value on the table, and it’s helping a lot of dairies keep doors open and invest in what matters—better fresh-cow facilities, healthier transition programs, more comfortable housing, improved butterfat performance.

At the same time, reports from CoBank remind us we can’t pull replacements out of thin air. If everyone leans too hard into beef‑on‑dairy at once, the industry doesn’t magically get the heifers it needs in 2027 or 2028. Somebody ends up short—and often it’s the operations that didn’t see the shortfall coming.

The goal here isn’t to scare anyone away from beef‑on‑dairy. It’s to help you turn today’s beef premiums into durable, long‑term profit—without waking up two years from now wondering where the replacements went.

If there’s one step worth taking in the next 30 days:

- Put your current heifer numbers and realistic replacement needs on a single page.

- Project them out 18–24 months.

- Let that picture have a real say in how much beef semen you use this year.

It doesn’t require perfect data. Just honest numbers. And that quiet little habit is often what separates the herds that “manage to get by” from the ones that keep growing and improving—no matter what Brazil, the cattle futures, or the next drought throws at them.

At The Bullvine, we’ll keep tracking these shifts so you’ve got the information and tools you need to play the whole game, not just the next move.

Key Takeaways:

- $1,400 calves today, $3,500 heifers in 2027: The beef-on-dairy math only works if your replacement pipeline can handle it—and for many herds, it can’t

- The shortage is already locked in: U.S. heifer inventories hit a 20-year low, CoBank projects 800,000 head short by 2027, and new processing plants are coming online hungry for milk

- Every breeding decision is a 24-month bet: By the time heifer prices scream, the shortage was set two years ago—waiting for signals means you’re already behind

- Adjust in steps, not panic: Dropping beef semen 3-5 points per quarter protects your pipeline without blowing up this year’s cash flow

- A one-page dashboard can save you six figures: Track heifers by age against replacement needs monthly, and you’ll see the gap before it becomes a $3,500-per-head crisis

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Beef-on-Dairy’s $6,215 Secret: Why 72% of Herds Are Playing It Wrong – Stop leaking cash by treating beef-on-dairy like a side hustle. This deep dive delivers the reproductive benchmarks and tiered management protocols that separate elite $6,000/month profit-makers from the 72% of herds currently playing the game wrong.

- 18 Months to Fix Your Dairy Math: Culls, Heifers and Processor Power in the New Dairy Reality – Arms you with a five-year strategy to navigate the collision between disappearing heifers and $10 billion in new processing capacity. It breaks down the “new culling math” and processor leverage moves you must make today.

- Genetic Revolution: How Record-Breaking Milk Components Are Reshaping Dairy’s Future – Reveals how the 2025 genetic reset and genomic multipliers are “designing” the 2035 herd. Gain an immediate advantage by aligning your breeding strategy with the massive 41% weighting increase in feed efficiency and record-high component values.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.