Hope is not a strategy. Nostalgia is not a business plan. Three hundred fifty-seven thousand heifers short and $200K on the line—here’s the math dairies need now.

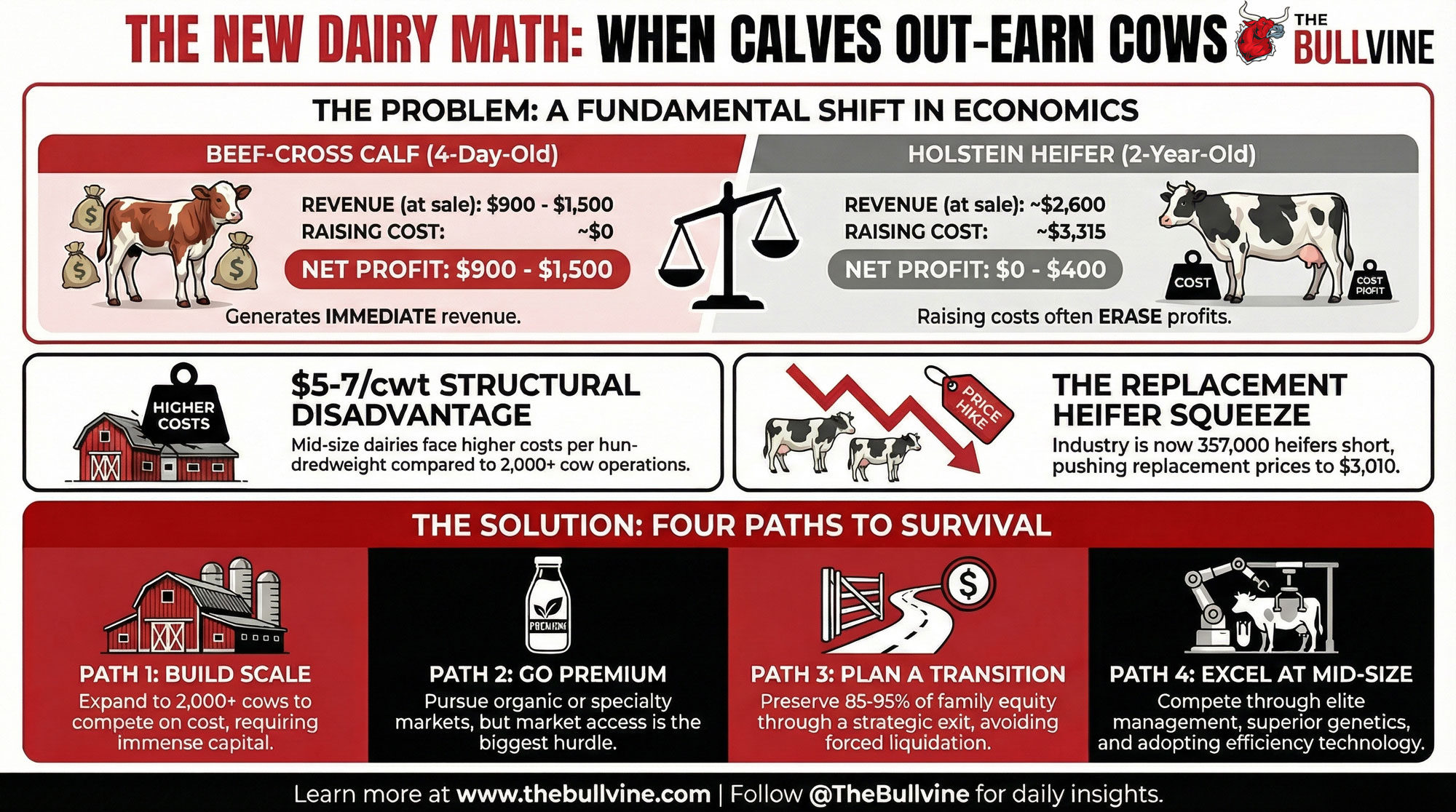

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: A beef-cross calf at four days old now generates more profit than a Holstein heifer does after two years—and for mid-size dairies, that shift represents $200,000-$300,000 in annual revenue sitting on breeding decisions. Beef-cross calves fetch $900-$1,500 while heifer-raising nets $0-400 after $3,315 in average costs. Three structural forces have converged: butterfat oversupply from genetic progress, China’s 75-85% self-sufficiency killing export recovery hopes, and processor consolidation creating $5-7/cwt disadvantages for mid-size suppliers. The industry is now 357,000 heifers short with replacements at $3,010 nationally, per CoBank’s August 2025 analysis. Four paths remain for mid-size operations—scale aggressively, pursue premium markets, execute planned transitions that preserve 85-95% of equity, or achieve the operational excellence that makes mid-size sustainable. Hope is not a strategy; families preserving wealth are deciding in months 6-10, during margin pressure, not in month 18, when options have narrowed, and equity has eroded.

Something worth paying attention to is happening on dairy operations across North America, and honestly, I don’t think it’s getting the discussion it deserves. A beef-cross calf sold at four days old now generates somewhere between $900 and $1,500 in revenue, depending on your market and genetics. Meanwhile, a Holstein heifer calf—after 24 months of feeding, housing, breeding, and veterinary care—often produces milk worth roughly the same in annual margin contribution.

I know. It sounds backwards. But the numbers are real.

Here’s the uncomfortable question nobody wants to ask at the coffee shop: Why are so many operations still raising every heifer calf like it’s 2015? The answer usually has more to do with tradition than spreadsheets—and that’s a problem when margins are this tight.

What we’re looking at is a meaningful shift in how successful operations are thinking about revenue streams, genetic decisions, and the fundamental question of where their margins actually come from. For mid-size operations—those running 300 to 1,000 cows—understanding this shift matters a great deal for long-term planning.

The Revenue Picture Has Changed

Here’s what’s interesting about the current market. Premium beef-cross calves from Angus, Limousin, or Belgian Blue sires bred to dairy cows are commanding prices that would have raised eyebrows five years ago. USDA Agricultural Marketing Service data from late 2025 shows auction prices for quality dairy-beef crosses consistently exceeding $1,200 at major livestock markets in the East, with premium genetics pushing above $1,400 in strong markets.

Now, those numbers vary quite a bit by region—and that matters for your planning. The Bullvine’s market tracking shows beef-cross calves in the 60-100 pound range fetching $931-$1,075 per head at New Holland in Pennsylvania, while Wisconsin markets run $690-$945, and Minnesota comes in around $700-$985. California operations often see stronger prices due to proximity to feedlot demand, while Canadian producers face different dynamics under supply management. So your results will depend significantly on where you’re selling and what genetics you’re putting into those calves.

Meanwhile, the traditional replacement heifer model—which made solid economic sense when Holstein heifers sold for $2,800 and milk margins were healthier—now requires some careful penciling. And by “careful penciling,” I mean actually doing the math rather than assuming heifer-raising still works because your dad did it.

Here’s the practical math many operations are working through:

- Beef-cross calf at 4 days: $900-$1,300 average revenue, depending on market and genetics

- Holstein heifer at 24 months: $2,600 sale value minus roughly $2,500-$3,000 raising cost = $0-$400 net in many cases

- Difference: Often $700+ per animal favoring beef-on-dairy

That heifer raising cost deserves a moment here. Canfax’s 2024 analysis of 64 benchmark farms found average costs of about $3,315 per heifer, and Beef Research Canada’s 2023 work showed a range of $2,904 to $3,806, depending on the operation. Your costs might be lower if you’ve got cheap home-raised feed and efficient facilities—but they might also be higher than you think when you pencil in everything honestly.

And that’s the thing. In my experience, many operations haven’t honestly factored heifer-raising costs into their budgets in years, if ever. They keep doing it because they’ve always done it. That’s not a strategy—it’s a habit.

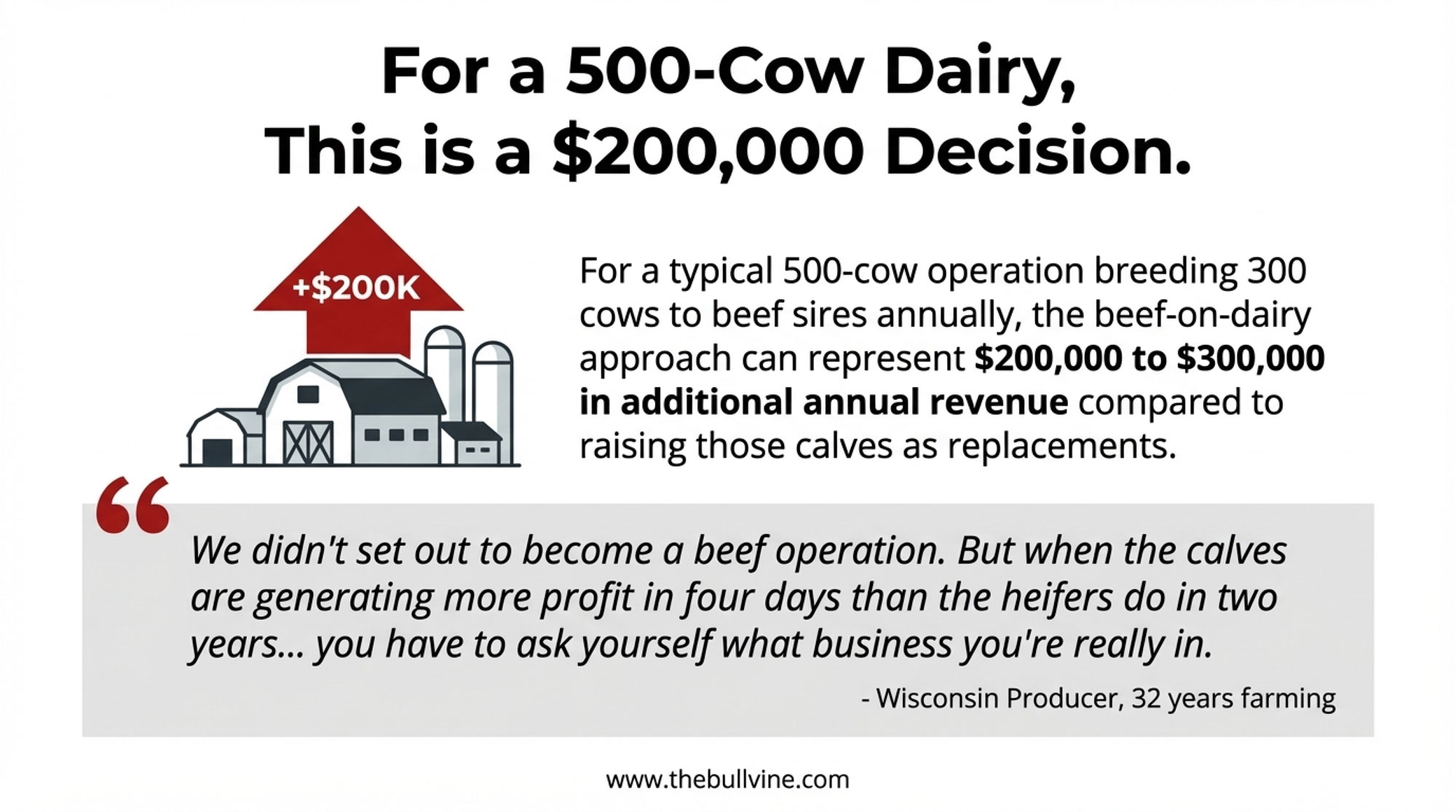

For a 500-cow operation breeding 300 cows to beef annually, the beef-on-dairy approach can represent $200,000 to $300,000 in additional revenue compared to raising all those calves as replacements. That’s meaningful money for operations working on tight margins.

I spoke with a Wisconsin producer recently who’s been farming for 32 years about this shift. “We didn’t set out to become a beef operation,” he told me. “But when the calves are generating more profit in four days than the heifers do in two years of work, you have to ask yourself what business you’re really in.”

Now, I want to be clear—beef-on-dairy isn’t right for every operation. Farms with genuinely superior heifer genetics, established replacement programs that actually pencil out, or specific breeding objectives may find the traditional model still makes sense for their situation. The key word there is “genuinely.” Too many operations claim their heifer program is profitable without ever running the real numbers. The key is running the actual math for your specific circumstances rather than assuming what worked in 2015 still pencils today.

Understanding What’s Driving These Changes

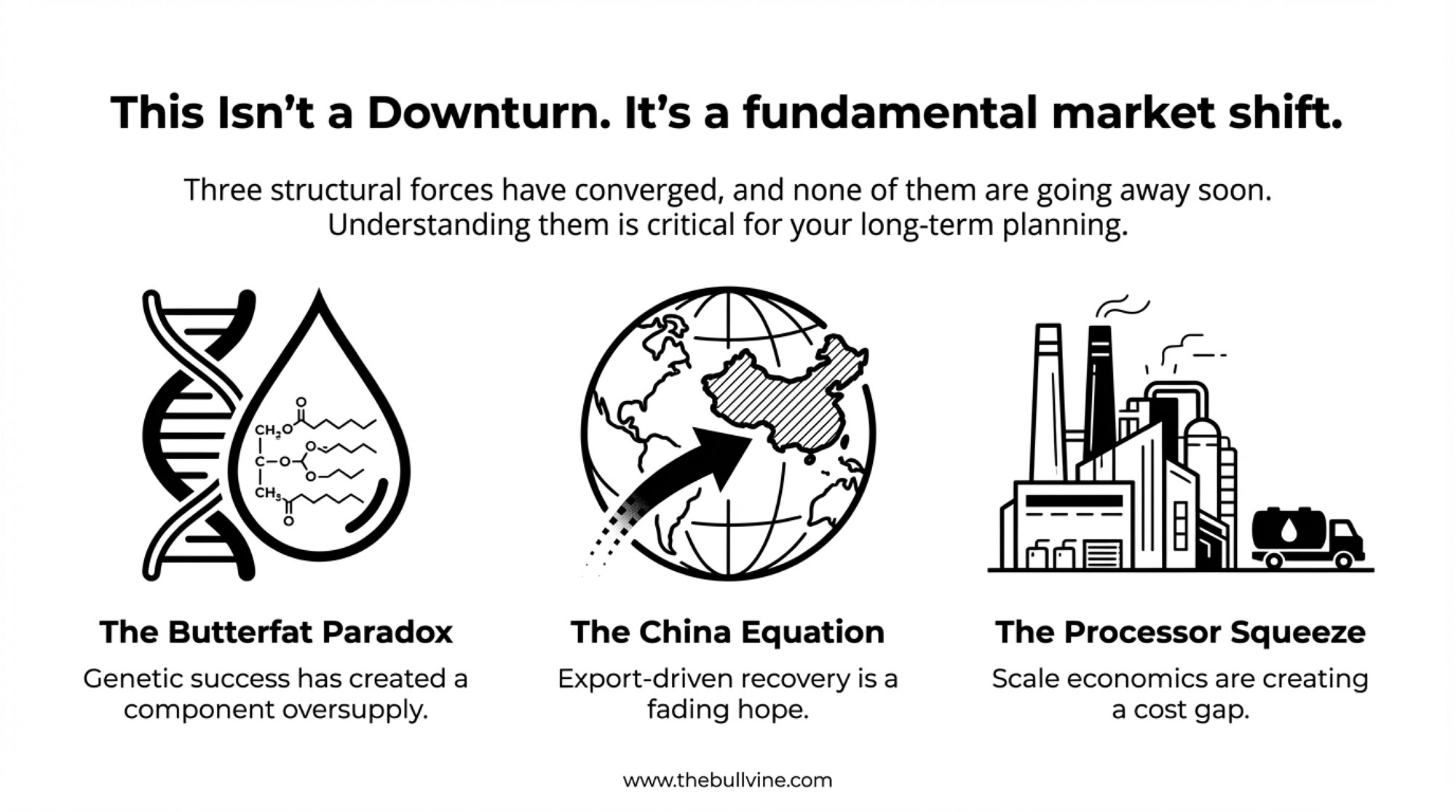

Three factors have converged to create the current environment. And what’s notable is that each one looks more structural than cyclical, which matters for planning purposes. This isn’t a two-year downturn you can wait out.

The Butterfat Genetics Story

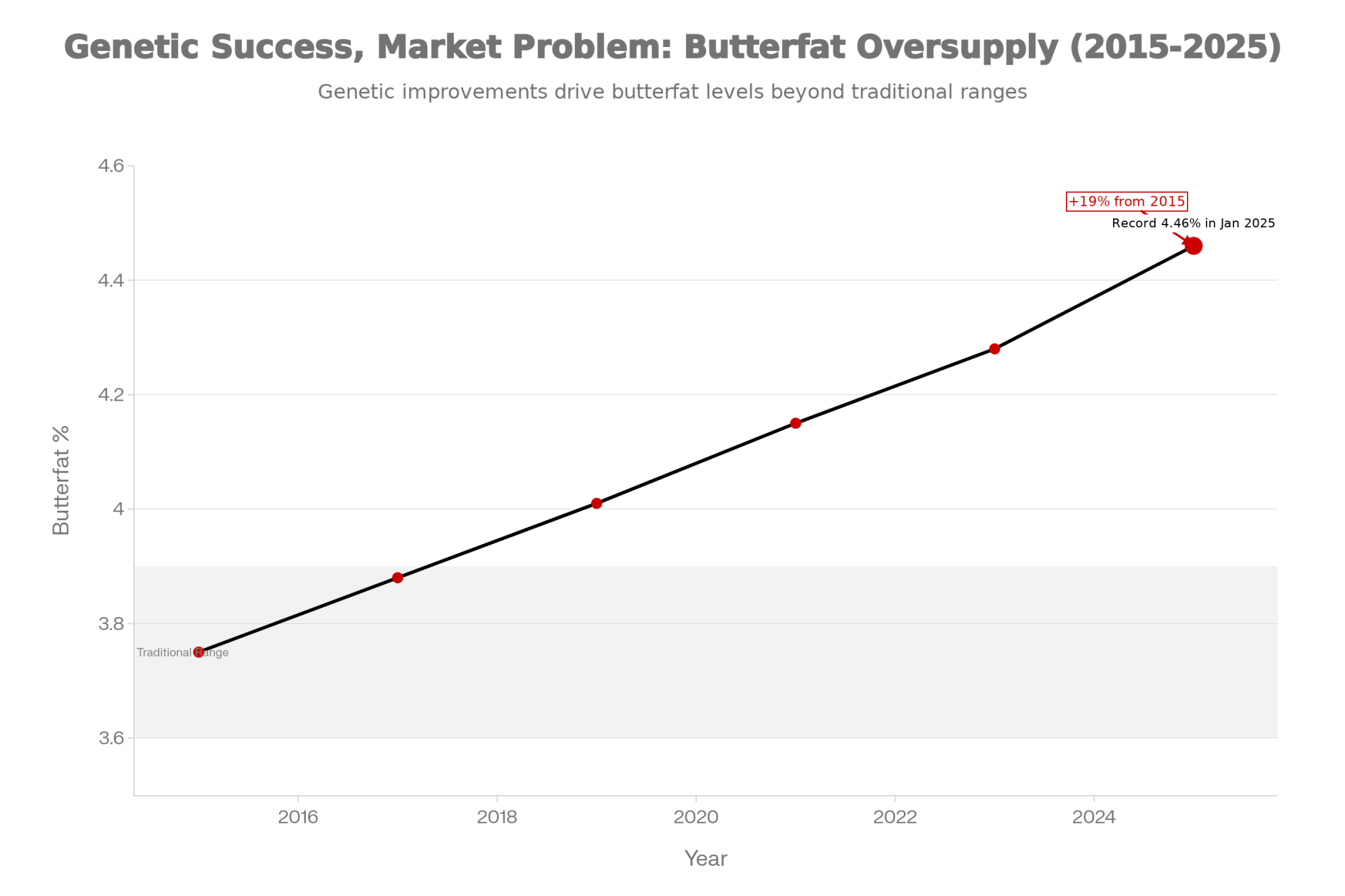

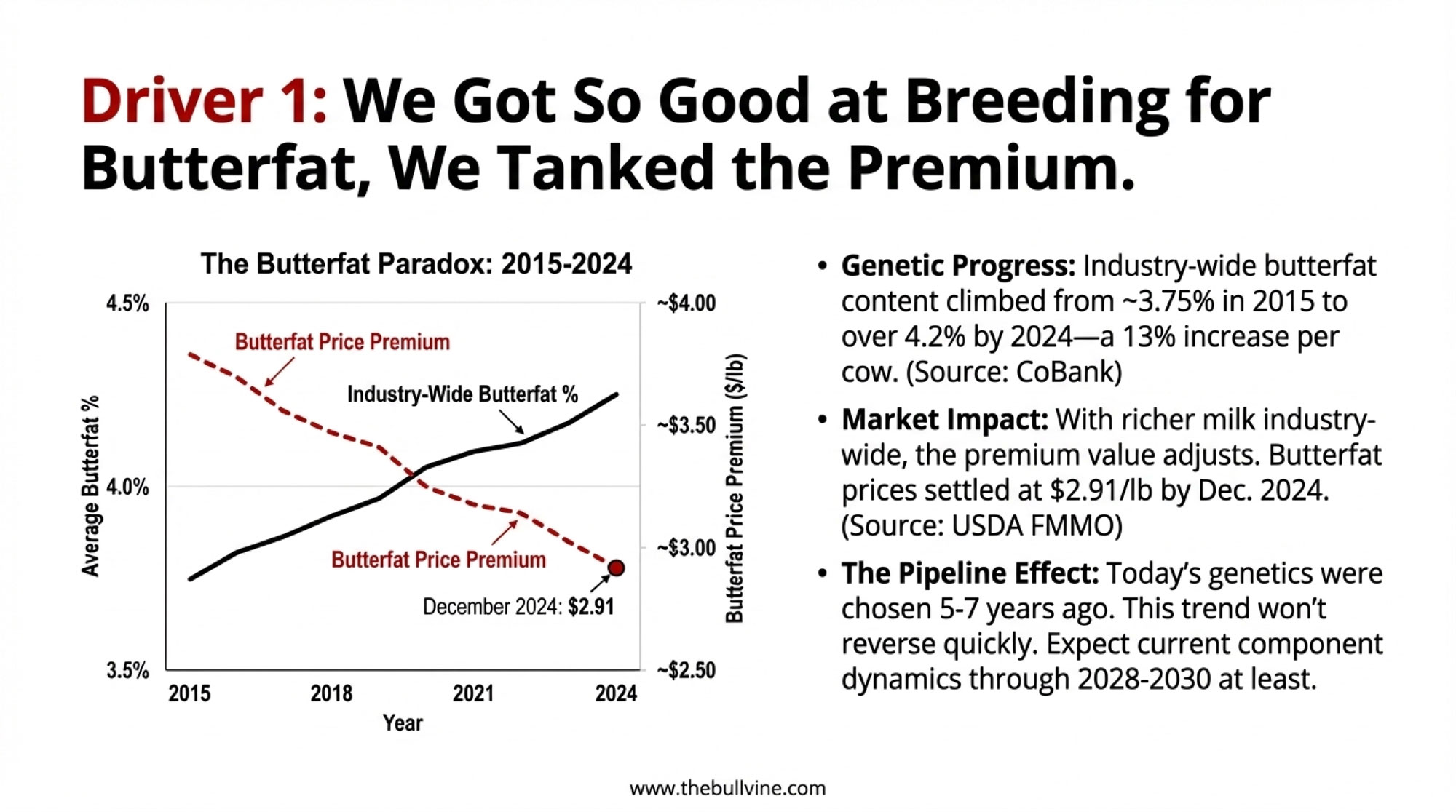

North American dairy genetics programs spent 15 years successfully breeding for higher butterfat content. By most measures, they achieved exactly what they set out to do. CoBank’s analysis shows butterfat percentages climbed from around 3.75% in 2015 to over 4.2% by 2024—a 13% increase in component production per cow. Butterfat levels in January 2025 hit a record 4.46% in some markets.

That’s genuinely impressive genetic progress. Here’s where it gets complicated from a market perspective, though.

These genetic improvements are now hitting markets simultaneously across much of the industry. When a large portion of cows produce richer milk, the premium value of those components naturally adjusts. We saw butterfat prices decline significantly through 2024, with USDA Federal Milk Marketing Order data showing butterfat settling at $2.91 per pound by December 2024—down from stronger premiums earlier in the year.

The genetic pipeline creates a timing consideration that I don’t think gets enough attention in these conversations. Bulls used today were evaluated 5-7 years ago, when butterfat premiums were steadily climbing. The market environment has evolved, but genetic decisions made years ago are still working through the system. Operations probably won’t see meaningful adjustment in their milking strings until 2028-2030 at the earliest.

This isn’t anyone’s fault—it’s simply how long-term genetic selection interacts with shorter-term market cycles. But it does mean the component dynamics we’re seeing won’t reverse quickly.

Global Demand Patterns Have Shifted

For two decades, China’s growing middle class drove global dairy demand projections. You know the story—expansion plans, processor investments, and price forecasts often included Chinese import growth as a key assumption. Many of us built business plans around that expectation.

That picture has evolved considerably. According to Rabobank’s Global Dairy Quarterly analysis, China has added over 11 million metric tons of domestic production capacity since 2018 and has moved toward approximately 75-85% self-sufficiency in dairy. That’s a dramatic shift from where they were a decade ago.

Rabobank’s analysts suggest this represents a more permanent structural change rather than a cyclical dip. The infrastructure investments China has made in domestic production indicate that it’s building for long-term self-sufficiency, not for temporary import substitution.

For North American producers, this means export-driven price recovery depends on developing other markets, which is certainly possible, but represents a different timeline and strategy than waiting for Chinese demand to return to previous growth patterns. Mexico has become an increasingly important market, as CoBank has noted, but it’s a different dynamic than the rapid growth we saw from China in the 2010s.

If your business plan depends on “prices have to come back eventually,” it might be time for a new business plan.

Processor Economics Are Evolving

Modern dairy processing plants need substantial daily volume to operate efficiently—we’re talking several million pounds daily for competitive economics. This reality naturally favors fewer, larger suppliers from an operational standpoint.

A 500-cow operation producing 33,000 pounds daily represents a relatively small portion of a major processor’s intake needs. And when processors are investing billions in new capacity—industry reports show over $10 billion in dairy processing infrastructure investment through 2028—they’re designing facilities around large-volume supplier relationships.

Transportation economics factor in as well. Consolidated pickup routes to larger operations create real cost savings for processors, savings that either flow to large farms through better contract pricing or improve processor margins. Either way, that dynamic doesn’t particularly benefit mid-size suppliers trying to maintain competitive market access.

For cooperative members, these dynamics create additional considerations. Voting power in many cooperatives correlates with volume, which can affect how mid-size operations see their interests represented in cooperative decision-making. A 500-cow operation and a 5,000-cow operation technically have equal membership status, but their influence on cooperative strategy often differs considerably. I’ve watched cooperative boards approve hauling route consolidations and component pricing structures that made sense for their largest members while quietly disadvantaging the mid-size operations that historically formed their base.

That’s not a blanket criticism of cooperatives—some have adopted modified voting structures or regional representation models that give individual producers more proportional voice, and the cooperative model still provides genuine value for many operations. But the governance dynamics are worth understanding as you think about your market position and long-term relationships.

The Mid-Size Cost Picture

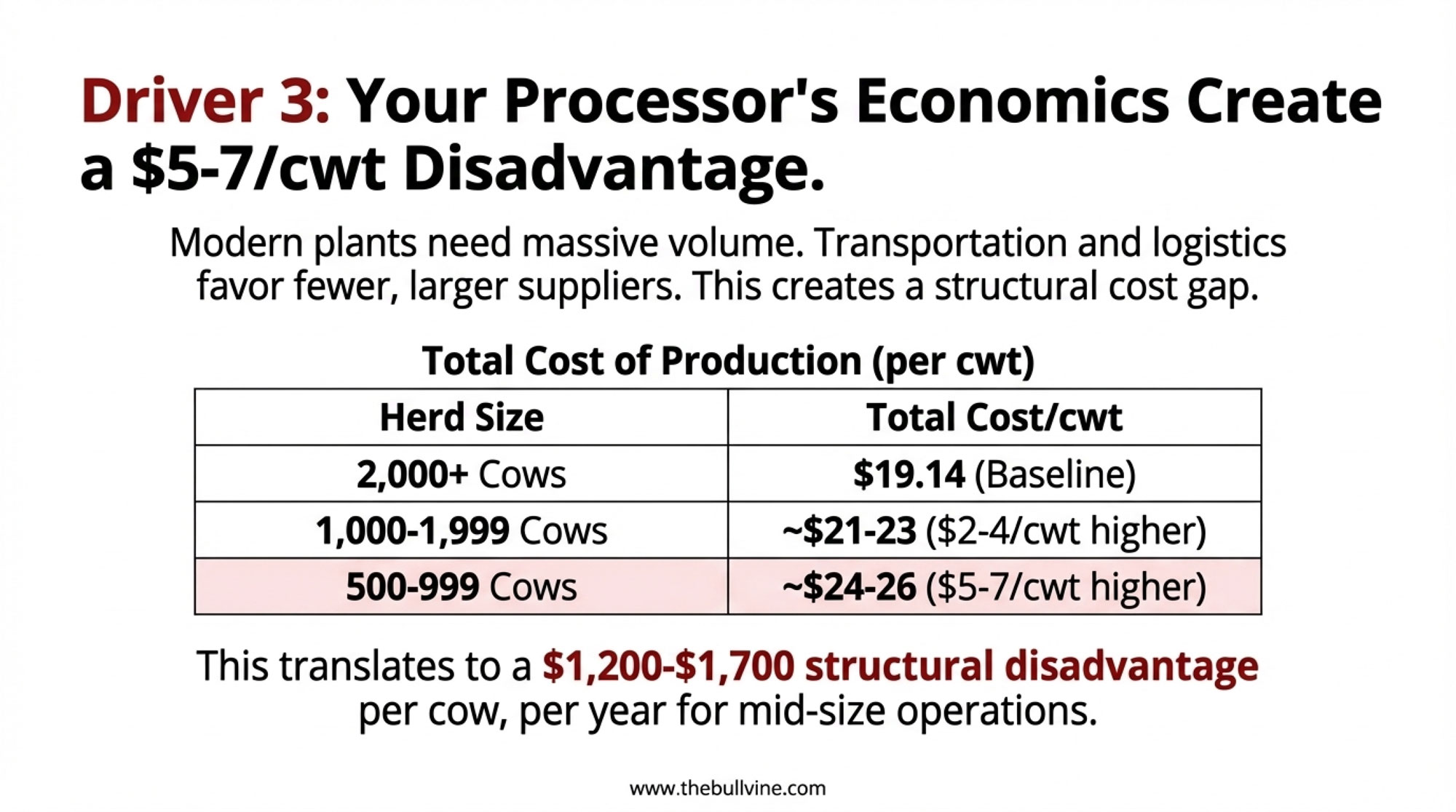

USDA Economic Research Service cost-of-production data reveals patterns worth understanding for operations in the 300-1,000 cow range. And I’ll be honest—these numbers can be sobering, but they’re important to face clearly.

| Herd Size | Total Cost/CWT | Difference vs. 2,000+ Cows |

| 500-999 cows | ~$24-26 | $5-7/cwt higher |

| 1,000-1,999 | ~$21-23 | $2-4/cwt higher |

| 2,000+ cows | $19.14 | Baseline |

Based on USDA ERS Milk Cost of Production Estimates, 2021 data—the most recent comprehensive survey available

That cost gap of roughly $5-7 per hundredweight translates to approximately $1,200-$1,700 in structural disadvantage per cow annually. Those are significant numbers that affect long-term competitiveness regardless of how well you manage day-to-day operations.

Where does this cost difference come from? It’s distributed across several areas that you probably recognize intuitively:

- Labor efficiency: Larger operations typically spread management and specialized labor across more production, achieving better output per worker

- Feed procurement: Volume buyers often negotiate 10-15% lower prices on concentrates through direct mill contracts

- Capital costs: Facility and equipment depreciation spreads across more production units

- Professional services: Veterinary, nutrition, and accounting fees get divided by more cows

Now, these figures represent national averages, and your situation may differ significantly. Regional variations matter quite a bit. California operations face environmental compliance costs that Midwest farms largely don’t carry. Wisconsin and Pennsylvania operations deal with different land costs and climate considerations than Texas dairies. Your specific costs depend on your specific circumstances—which is why it’s worth penciling your actual numbers rather than assuming you match the averages.

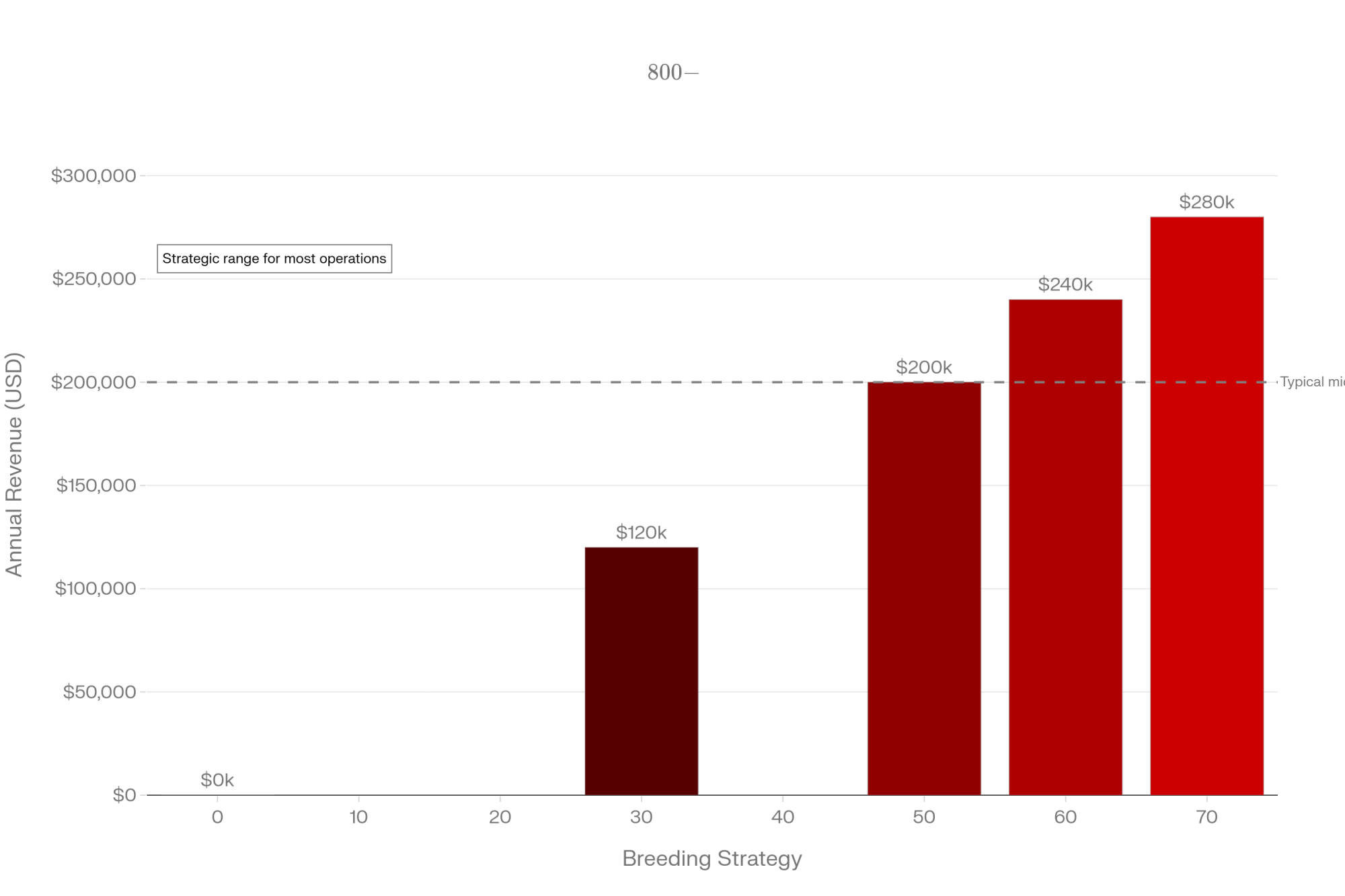

Beef-on-dairy revenue helps offset these structural differences. Based on current calf prices, it might cover roughly 40-50% of that gap for many operations. That’s meaningful, though it doesn’t eliminate the underlying economics entirely.

The Replacement Heifer Squeeze

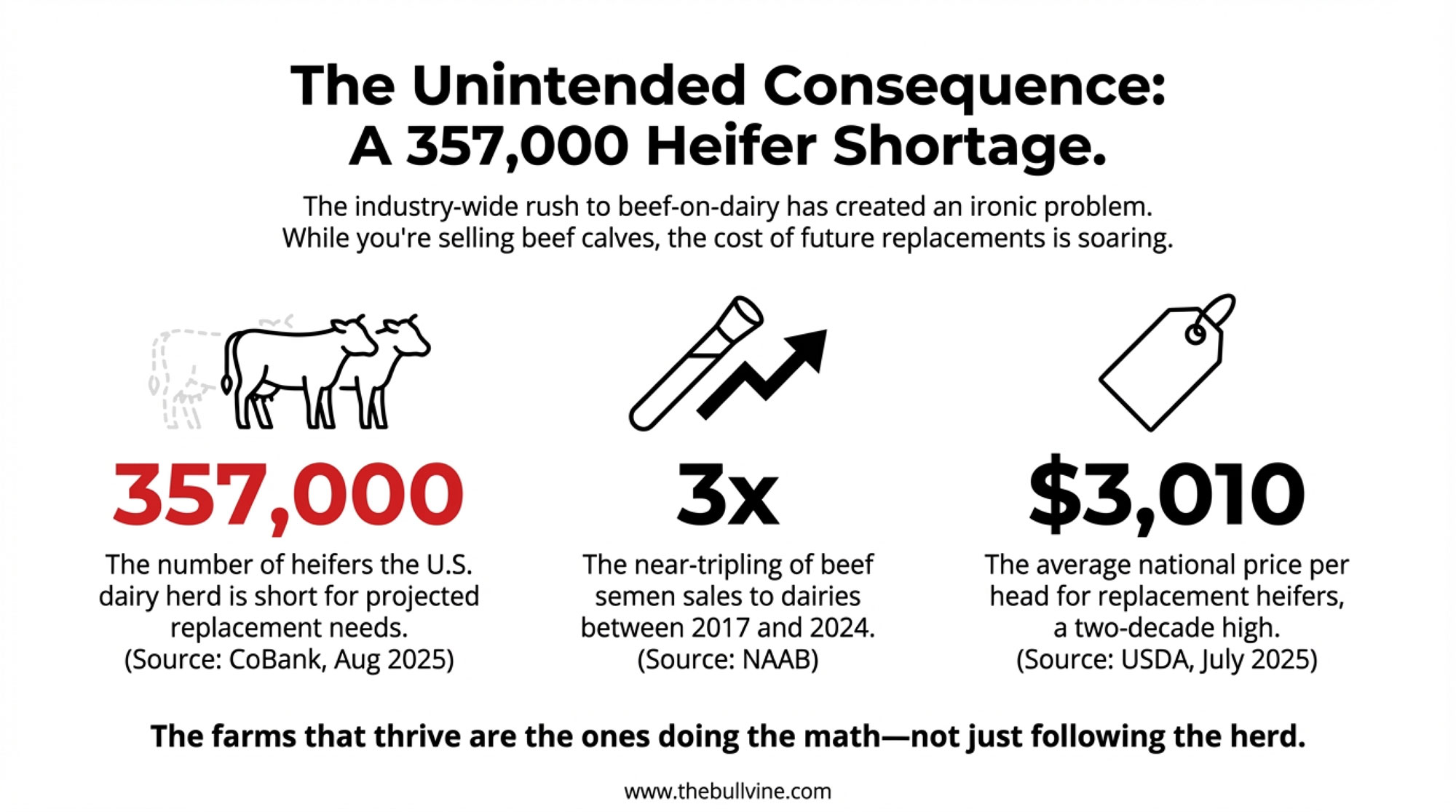

There’s another dimension to this that complicates the picture—and frankly, reveals the consequences of industry-wide groupthink. The widespread adoption of beef-on-dairy breeding has created something of a heifer shortage across the industry. CoBank’s August 2025 dairy analysis indicates the U.S. dairy herd is running approximately 357,000 heifers short of projected replacement needs—a direct consequence of so many operations shifting breeding priorities toward beef genetics.

This shortage has pushed replacement heifer prices to levels we haven’t seen in two decades. USDA’s July 2025 Agricultural Prices report showed replacement heifers averaging $3,010 per head nationally, with top genetics commanding $4,000 or more at California and Minnesota auction barns.

The irony isn’t lost on me: an industry that spent decades telling farmers to “raise your own replacements no matter what” has now swung to an equally thoughtless extreme of “breed everything to beef.” Beef semen sales to dairies nearly tripled between 2017 and 2020, reaching 7.9 million units by 2024, according to NAAB data. Neither the old approach nor the new one involves actually analyzing what makes sense for your specific operation. The farms that will thrive are the ones doing the math—not following the herd in either direction.

But here’s the catch—and it’s worth thinking about carefully. If you’re planning to exit the industry in 3-5 years, the beef-on-dairy math works fine. If you’re planning to operate for another 20 years, you’re eventually going to need those replacements—and they may be harder and more expensive to find.

Four Paths Worth Considering

Producers working through margin challenges generally have four strategic directions available. The key—and I can’t emphasize this enough—is to assess which path fits your specific situation honestly, rather than pursuing the one that sounds best, feels most comfortable, or lets you avoid difficult conversations with family.

Path 1: Building Scale

This tends to work for: Operations with strong debt service coverage—generally above 2.0-2.5—manageable debt-to-asset ratios below 40-45%, clear succession plans, and confident processor relationships.

Scaling from 500 to 2,000+ cows represents a significant undertaking. We’re talking substantial capital—often $10-15 million or more, depending on your starting point and approach—plus considerable additional land to meet nutrient management compliance requirements. The financial and management prerequisites are demanding.

Based on what I’ve observed over the years, a relatively small percentage of mid-size operations are genuinely positioned to pursue this path successfully. That’s not a criticism—it’s just an acknowledgment of the financial realities involved. The problem is that too many operations pursue expansion because it feels like “doing something” rather than because the fundamentals actually support it. Expanding into a cost structure you still can’t compete in just means losing money faster.

What successful scaling typically involves:

- Multi-year timeline from decision to full operation—often 5-7 years

- Major milking infrastructure investment for robotics or rotary systems

- Management systems that can function without daily owner involvement in routine decisions

- Strong processor relationships with confirmed market access at expanded volume

Penn State Extension has noted that operations seeking expansion financing typically need to demonstrate sustained positive cash flow history and strong management capacity before lenders will seriously consider major facility loans. That generally means having your current operation running well before taking on expansion debt.

I should mention that scaling does work for some operations. A central Indiana dairy I’ve followed grew from 600 to 2,400 cows over eight years by acquiring a neighboring operation, investing heavily in robotics, and securing a long-term processor contract before breaking ground. But they started with a debt-to-asset ratio under 30% and two generations actively involved in management. The prerequisites were there before the expansion began. They didn’t expand, hoping to fix their problems—they expanded because they’d already solved them.

Path 2: Premium Market Positioning

This tends to work for: Smaller operations—often under 200-250 cows—with strong balance sheets, secured processor contracts for specialty milk, and a willingness to fundamentally change their operational approach.

The challenge for mid-size operations pursuing this path is significant. Organic certification requires extensive pasture access—typically several hundred acres of quality grazing land for a larger herd. Feed costs increase 30-80% with organic inputs, and production often dips 10-15% during the transition period.

Perhaps most critically, organic processors in several major dairy regions report adequate or surplus supply and aren’t actively seeking new large-volume suppliers. The premium is attractive on paper, but market access is often the limiting factor in practice. You can get certified, but that doesn’t guarantee someone wants to buy your organic milk at organic prices. I’ve watched operations spend 18 months and significant capital to achieve organic certification, only to discover there’s no market for their milk at organic premiums. That’s an expensive lesson in checking market access before making production changes.

A2 milk and other specialty designations present similar market access considerations. These segments remain relatively small portions of total fluid milk sales, and most specialty processors have established supplier relationships they’re not looking to expand significantly.

One exception worth noting: Direct-to-consumer models with on-farm processing can work quite well at 50-150 cow scale, potentially capturing 60-80% of retail margin rather than commodity pricing. This does require significant processing infrastructure investment—$250,000-$600,000 isn’t unusual—and fundamentally different business skills. You’re essentially building a retail and marketing business that happens to have cows. Different game entirely, but it works for some folks with the right location, skills, and appetite for that kind of venture.

Path 3: Planned Transition

This may make sense for Operations where the primary operator is approaching retirement age without a clear succession plan, where debt service is consuming too much cash flow, where breakeven costs significantly exceed market prices, or where the operation has experienced extended periods of negative cash flow.

And here’s something I want to say directly: suggesting that some operations should consider transition isn’t a criticism of those farms or their management. Markets change. Cost structures evolve. Making a thoughtful decision to preserve family wealth is good business management, not failure.

What I will criticize is the stubborn refusal to consider transition when the numbers clearly indicate it’s time. I’ve seen too many families lose $500,000 or more in equity by waiting too long, hoping things would turn around, and being unwilling to have honest conversations about the future. That’s not perseverance—it’s denial dressed up as virtue. And it devastates families financially.

What makes planned transition more viable today than in previous challenging periods is that beef-on-dairy revenue can maintain positive cash flow during a drawdown. That $200,000-$300,000 in annual beef-cross revenue provides working capital for orderly asset sales at reasonable market value rather than distressed pricing.

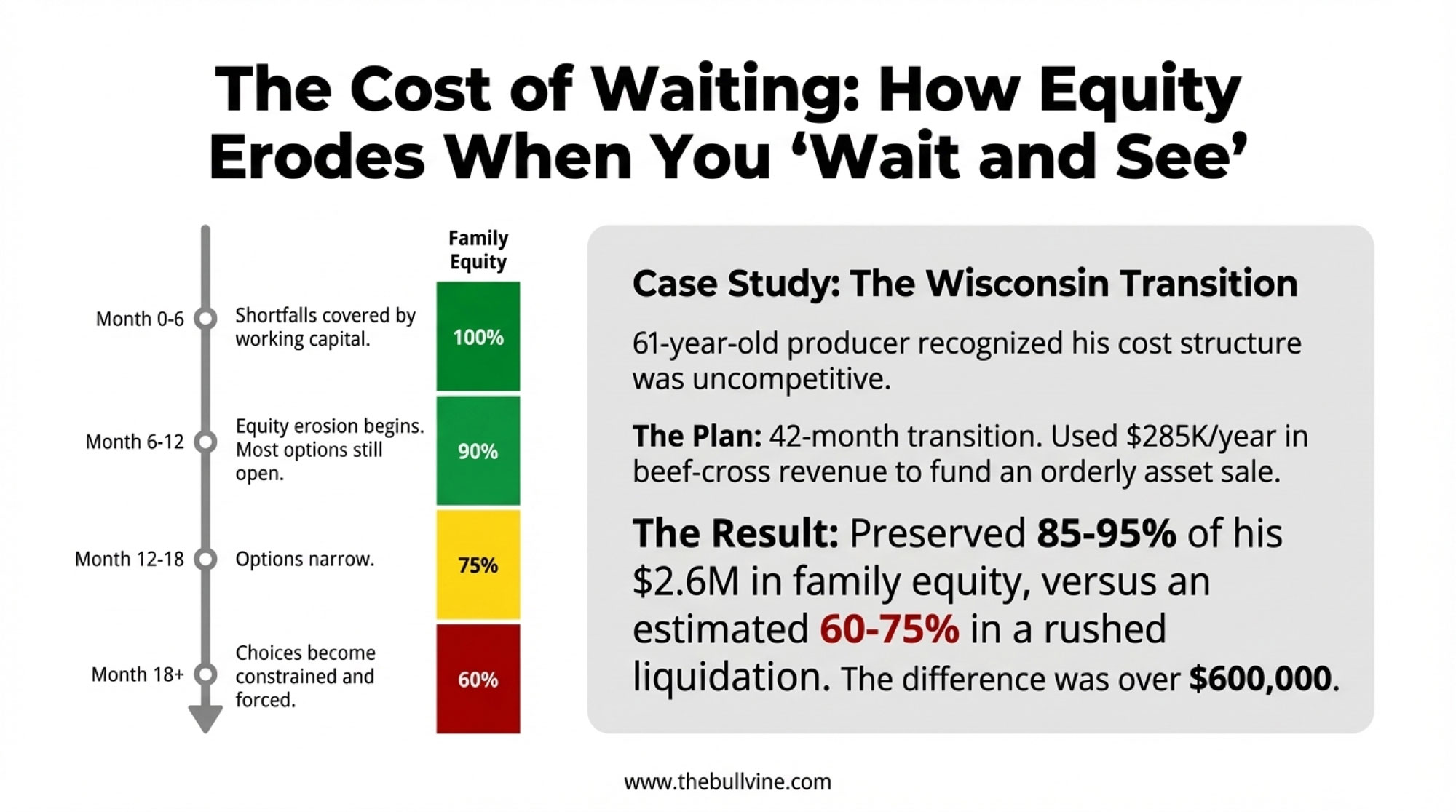

The equity preservation difference can be substantial:

- Planned transition over 36-48 months: Families typically preserve 85-95% of asset value

- Rushed liquidation after extended losses: Families often preserve 60-75% of asset value

For an operation with $3 million in net worth, that difference can exceed $600,000 in actual preserved family equity. That represents real money for retirement, for the next generation’s opportunities, or for whatever comes next.

Path 4: Making Mid-Size Work

I’d be doing you a disservice if I didn’t mention that some mid-size operations are genuinely finding ways to compete—and the research backs this up. University of Vermont Extension’s 2024 dairy economics analysis found that operations in the 400-600 cow range implementing robotic milking systems achieved labor cost reductions averaging 15-18%, which began to close the efficiency gap with larger operations meaningfully.

A 650-cow Vermont operation I’ve followed has carved out a sustainable position by combining aggressive robotic milking efficiency with a local processor relationship that values consistent quality and year-round supply stability over raw volume—and they’ve kept heifer-raising in-house because their genetics actually command premium replacement prices that make the math work. Their fresh cow protocols and transition period management have pushed their rolling herd average well above regional benchmarks, which gives them leverage in processor negotiations that most mid-size operations don’t have.

It’s not easy, and it requires exceptional management in multiple dimensions simultaneously. But it’s worth noting that “mid-size is doomed” isn’t universally true. It’s just that this path requires you to be genuinely excellent at several things at once, not just average at everything. If you’ve got superior genetics, strong local processor relationships, and the management capacity to optimize every efficiency lever available—robotics, feed management, reproduction, cow comfort—mid-size can still work. You just can’t afford to be mediocre at any of it.

A Framework for Decision-Making

When producers work through these decisions with their CPA and agricultural lender, several metrics typically guide the conversation. Understanding these ahead of time can make those discussions more productive.

Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR)

This ratio measures the cushion between income and debt payments. Lenders watch this number closely—it’s often the first thing they calculate.

- Formula: Net operating income ÷ Total annual debt service

- Above 2.0: Generally solid position for considering strategic investments

- 1.5-2.0: Optimization makes sense; expansion capacity may be limited

- Below 1.25: Transition planning deserves serious consideration

True Cost Analysis

One pattern I’ve noticed over the years: producers often underestimate their actual breakeven by not accounting for costs that don’t show up as monthly payments but are economically real:

- Operator labor at what you’d pay a hired manager—$65,000-$95,000 annually isn’t unreasonable in many markets

- Return on your equity could earn in alternative investments—typically 4-6%

- Deferred maintenance is accumulating on facilities

When these factors are honestly included, some operations discover that their true economic breakeven point significantly exceeds current milk prices. That’s uncomfortable to realize, but better to know it than not. And frankly, if you’re not willing to calculate your true breakeven because you’re afraid of what you’ll find, that tells you something important right there.

Stress Testing

Experienced lenders evaluate what happens to your DSCR if milk drops $2 per hundredweight while feed costs rise 10%. It’s worth doing that calculation yourself before you’re sitting in the loan officer’s office. Operations that look marginal under that scenario typically face limited options for expansion financing.

Five Questions for Your Next Lender Meeting

Before you sit down with your agricultural lender or CPA, work through these honestly:

- What’s your true all-in breakeven? Include operator labor at replacement cost, opportunity cost on equity, and deferred maintenance. If this number scares you, that’s information.

- What happens to your DSCR if milk drops $2/cwt and feed rises 10%? If you go below 1.25 under that scenario, your strategic options are already narrowing.

- Are you strategic to your processor, or easily replaced? If your milk disappeared tomorrow, would they notice—or just shift a route?

- What’s your succession plan—documented, not assumed? Verbal family interest isn’t the same as committed next-generation involvement with financial analysis.

- If you’re considering expansion, are you doing so because the fundamentals support it, or because it feels better than the alternatives? Be honest with yourself here.

Timing Considerations

What I’ve observed over the years is a fairly consistent pattern once operations enter challenging cash flow territory:

- Months 0-6: Operating shortfalls often get covered by savings and working capital

- Months 6-12: Equity erosion becomes more noticeable; most strategic options remain available

- Months 12-18: The situation typically demands more immediate attention; options narrow

- Month 18+: Choices become more constrained

The practical insight here is that decisions made earlier in this timeline—during months 6-10, say—tend to preserve more options and more equity than decisions made later. Waiting and hoping for market improvement is completely understandable… but it has real costs. Every month of delay is a decision—it’s just a decision not to decide, which is often the most expensive choice of all.

Beef-on-dairy revenue can extend these timelines somewhat, providing breathing room that previous generations of struggling dairy farms didn’t have. But it doesn’t change the underlying economics. An operation generating $300,000 in beef-cross revenue while facing $500,000 in other losses is still experiencing $200,000 in annual equity erosion. The beef revenue buys time for better decisions—not infinite time.

What Successful Transitions Look Like

A Wisconsin Example

A 61-year-old producer I’ve followed over the past few years recognized, around month 7, that his cost structure wouldn’t allow him to compete effectively long-term at his current scale. Rather than waiting indefinitely—or worse, doubling down on a strategy that wasn’t working—he implemented a 42-month planned transition:

- Increased beef breeding to 70% of the herd for revenue optimization

- Generated approximately $285,000 annually in beef-cross calf sales

- Reduced herd size gradually while maintaining processor relationships and milk quality

- Marketed real estate with an 18-month timeline, allowing proper buyer qualification rather than a rushed 60-day distressed sale

Result: Preserved $2.6 million in family equity—substantially more than a rushed liquidation would have yielded.

He now manages cropland for neighboring operations at around $55,000 annually while drawing income from invested assets. His total annual income actually increased, and his working hours dropped considerably. Not the outcome he’d imagined when he started farming, but a genuinely good outcome for his family.

“The hardest part wasn’t seeing the numbers—those were clear enough. The hardest part was accepting that the market had changed in ways I couldn’t control or wait out. Once I made peace with that, the decisions got a lot simpler.”

— Wisconsin dairy producer, 32 years in operation

His son, who had considered returning to the family operation, used his share of the preserved assets to start a successful trucking business. Different path, but solid financial foundation—which was really the goal all along.

Practical Takeaways

Assessing your current position:

- Calculate the true all-in breakeven, including the opportunity costs that are easy to overlook

- Run stress-test scenarios—milk down $2, feed up 10%—before your lender does

- Evaluate succession plans honestly. Verbal family interest isn’t the same as documented commitment with financial analysis

- Assess your processor relationship realistically. Are you strategic to them, or easily replaced?

If considering growth:

- Verify you meet financial thresholds before investing in detailed planning

- Secure processor commitment for expanded volume before major capital decisions

- Document succession planning with realistic financial projections

- Plan for multi-year implementation with regular evaluation points

- Be honest: Are you expanding because the fundamentals support it, or because it feels better than the alternatives?

If considering premium markets:

- Confirm market access before beginning any conversion—certification without a buyer isn’t worth much

- Recognize that finding a processor often matters more than achieving certification

- Evaluate direct-to-consumer models if scale and location support them

- Budget realistically for transition periods with uncertain cash flow

If pursuing mid-size excellence:

- Identify your genuine competitive advantages—don’t assume you have them

- Invest in efficiency technology where ROI is demonstrable

- Build processor relationships based on quality, consistency, and reliability

- Evaluate whether your genetics actually justify keeping heifer-raising in-house

- Accept that this path requires excellence across multiple dimensions simultaneously

If considering transition:

- Make decisions while meaningful options remain available

- Use beef-on-dairy revenue to maintain positive cash flow during the process

- Engage qualified professionals—CPA, agricultural attorney—early rather than late

- Explore all available tools, including Chapter 12 provisions where applicable. Section 1232 can provide meaningful tax advantages in farm bankruptcy situations

For all operations:

- Beef-on-dairy provides valuable revenue flexibility, though it’s one tool among several

- Cost differences between herd sizes reflect structural economics that tend to persist

- Earlier decisions typically preserve more options than later ones

- Thoughtful wealth preservation honors what previous generations built—more than stubbornly running losses ever will

The Bottom Line

The North American dairy industry continues to evolve toward two primary models: larger-scale commodity production, where cost structures provide a competitive advantage, and smaller-scale operations, where premium positioning or direct consumer relationships create different economics.

Operations in the 300-1,000 cow range face a challenging middle position. Beef-on-dairy revenue helps considerably, but doesn’t fully resolve the underlying cost dynamics. Some operations will find ways to make mid-size work through exceptional execution on multiple fronts simultaneously—but that’s a narrow path that requires genuine excellence, not just determination.

That observation isn’t a criticism of mid-size operations or the people who run them. Many excellent managers operate in this range. But market structures have evolved in ways that create real challenges regardless of management quality. Pretending otherwise—or blaming the challenges on things you can’t control while ignoring the decisions you can make—doesn’t help anyone.

The producers who will be well-positioned in 2030 are the ones making clear-eyed assessments today: pursuing growth where the prerequisites genuinely exist, pivoting toward premium markets where access is available, finding the operational excellence to make mid-size sustainable where the skills and circumstances align, and transitioning thoughtfully where the underlying economics have shifted.

Each of these paths can lead to good outcomes for families. The path that tends to work poorly is waiting indefinitely for conditions to change while equity gradually erodes. Hope is not a strategy. Nostalgia is not a business plan.

Previous generations built these operations by adapting to market realities, not by ignoring them. That same practical wisdom—applied to today’s circumstances—will preserve these operations for the families who depend on them.

For operations working through these decisions, conversations with your agricultural lender and CPA provide a good starting point. The numbers for your specific situation may look quite different from industry averages—and understanding your actual position is the first step toward making good decisions.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- From $200 Holstein Bulls to $1400 Beef Crosses: Your 3-Week Implementation Guide – Stop breeding by habit and start managing for cash. This guide delivers a tactical three-week blueprint to audit your herd, integrate genomic testing, and pivot your bottom 30% into high-value terminal crosses immediately.

- Squeezed Out? A 12-Month Decision Guide for 300-1,000 Cow Dairies – Arm yourself with a 12-month survival framework designed specifically for the mid-size squeeze. This analysis reveals why the “middle” is vanishing and provides the hard data needed to choose your path before equity evaporates.

- Bred for $3 Butterfat, Selling at $2.50: Inside the 5-Year Gap That’s Reshaping Genetic Strategy – Expose the five-year “timing trap” currently poisoning genetic progress. This disruptor piece breaks down why today’s indices might be breeding for a market that no longer exists and delivers a smarter strategy for 2030 resilience.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!