Volume up 9 percent over last year, but sales to Asia lag in closing months of 2018.

U.S. dairy exports reached a record-high volume in 2018, increasing 9 percent over the prior year despite a fourth-quarter slowdown, according to trade data released today.

Suppliers shipped 2.188 million tons of milk powders, cheese, butterfat, whey products and lactose in 2018, and total dairy exports added up to 1.993 million tons (4.394 billion lbs.) of total milk solids. The value of U.S. exports was $5.59 billion, 2 percent more than the prior year.

In the face of retaliatory tariffs, global oversupply, weak commodity markets and other challenging headwinds, exports rose to an equivalent of 15.8 percent of U.S. milk solids production in 2018, the highest percentage ever in a calendar year.

Over the previous three years, exports were equivalent to 14.2 percent of production.

2018 Exports Reach Record 15.8 Percent of Production

.png?width=554&name=chart%202018%20-3%20(2).png)

U.S. export gains were led by record shipments of dry ingredients: nonfat dry milk/skim milk powder (NDM/SMP), high-protein whey products and lactose. However, performance was dimmed by a fourth-quarter slump, during which volume declined 11 percent year-over-year, after posting a 16 percent increase in the first three quarters.

In addition, the U.S. reclaimed the title of the world’s largest single-country cheese exporter.

2018 Volume Reaches Record 4.394 billion lbs.

.png?width=554&name=chart%202018-2%20(2).png)

Loss of sales to China—America’s third-largest single-country market—followed mid-year retaliatory tariffs, playing a role in the year-end decline. U.S. sales to China were up 17 percent in the first half of the year but fell 33 percent in the second half—a drop of more than 10,400 tons of product per month. Exports to Southeast Asia also faded toward year-end, sliding 18 percent in November-December, while shipments to Japan were down 10 percent throughout the second half.

Mexico and Southeast Asia remained the top two overseas destinations for U.S. dairy products in 2018, accounting for 39 percent of total export value. Canada, China and South Korea rounded out the top five markets. Among other markets, U.S. suppliers posted increased sales last year to the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) region and the Caribbean.

2018 Sets Volume Record — Despite Lagging 4th Quarter

.png?width=554&name=chart%202018-1%20(2).png)

To see more detailed, interactive charts on 2018 performance, click here.

Product highlights

U.S. exports of NDM/SMP totaled 715,491 tons in 2018, up 18 percent from the prior year, as U.S. suppliers took advantage of strong, broad-based global import demand. Sales to Mexico (up 25 percent, +70,761 tons, to 348,989 tons) reached a record high, and shipments to Southeast Asia (up 32 percent, +52,449 tons, to 216,077 tons) were the most ever as well, despite falling 25-percent short in the last two months of the year. These two markets accounted for more than three-quarters of U.S. NDM/SMP export volume. The Philippines remained the top market in Southeast Asia, and shipments to Indonesia and Vietnam increased 70 percent. In contrast, other key markets suffered losses: exports to China, Peru, Pakistan, Japan and the MENA region were just 70,561 tons in 2018, down 29 percent (-28,820 tons).

(USDEC has adjusted official U.S. Bureau of Census trade data for NDM/SMP and WMP since June 2016 to account for shipments we believe are misclassified.)

Cheese exports increased 2 percent in 2018 to 348,561 tons, making the United States the world’s largest single-country cheese exporter, a spot last held in 2013-2014. U.S. suppliers posted record sales to Central America (24,034 tons, +16 percent) and Southeast Asia (19,077 tons, +15 percent) and increased volume to South Korea (56,169 tons, +7 percent). Shipments to Mexico, the top market for U.S. cheese, were up fractionally for the year, tipping a new record high, and sales to Japan, the number-three market, were up 3 percent. However, these gains were offset by losses to Australia (-19 percent, -5,596 tons) and Canada (-35 percent, -4,075 tons).

Total whey exports were 545,890 tons, down fractionally compared with 2017 volume. Shipments of whey protein concentrate (WPC) were up 4 percent and sales of whey protein isolate (WPI) were up 20 percent. Both reached new highs. Exports of dry whey were up for the third straight year, finishing 2 percent above 2017 levels. Exports of modified whey (permeate), however, lagged prior year, dropping 13 percent.

Whey trade was impacted by China tariffs more than any other product category. Whereas China made up 45 percent of U.S. whey exports in 2017, it accounted for just 31 percent in the last six months of 2018. In the first half of the year, whey exports to China were up 3 percent. In the second half, after tariffs were put in place, exports were down 39 percent—a decline of 48,469 tons in six months. For the full year, whey exports to China were down 18 percent. Almost all the drop-off came in dry whey and modified whey (permeate).

Some of the decline was offset as U.S. suppliers diverted whey to Southeast Asia —which took record volumes in 2018—as well as Japan, South Korea and Mexico. Exports to Southeast Asia were up 28 percent (+23,744 tons), while shipments to Japan were up 26 percent (+7,011 tons), South Korea was up 41 percent (+4,658 tons) and Mexico was up 9 percent (+4,455 tons). Meanwhile, sales to Canada declined 22 percent (-9,700 tons).

Lactose exports totaled 392,166 tons in 2018, a 9-percent increase, though shipments slowed considerably in the fourth quarter. Most of the gains for the year were to China (+40 percent, +27,484 tons) and New Zealand (+27 percent, +8,673 tons).

Butterfat exports totaled 44,538 tons, up 61 percent, and the most since 2014. Gains were driven by record butterfat sales to Mexico (16,126 tons, almost all anhydrous milkfat). Butterfat shipments to Mexico were up 288 percent (+11,967 tons) from the prior year.

Exports of whole milk powder (WMP) and milk protein concentrate (MPC) also rebounded in 2018, posting their highest volumes in four years.

WMP shipments were 45,706 tons, up 80 percent from 2017 levels. The majority of the increase came from Southeast Asia (mostly Vietnam and Singapore), where sales were up more than three-fold to 19,741 tons.

MPC exports totaled 32,701 tons, up 40 percent. Sales to Mexico were the most in 10 years (11,699 tons, +37 percent, +3,138 tons); shipments to Canada more than doubled to 4,729 tons (+2,746 tons); and exports to the MENA region jumped 73 percent to 6,704 tons (+2,818 tons).

Shipments of fluid milk and cream were 115.4 million liters, up 9 percent. Most of the increase came in sales to Taiwan, which fell just short of being the number-one overseas market for U.S. fluid milk for the first time. Exports to Taiwan were nearly 37.7 million liters (+31 percent, +8.9 million liters). Suppliers also boosted sales to the Caribbean (+79 percent, +4.2 million liters). Meanwhile, exports to Mexico, still the leading market for U.S. milk/cream, were flat and shipments to Canada were down 2 percent.

One exception to the growth trend was food preps (blends), which hit an eight-year low export volume of 62,721 tons, down 13 percent. Sales to Canada, which accounted for more than half that volume, were off 2 percent, while shipments to all other major markets were down more significantly.

Source: U.S. DEC

The gate clanged close as Matt Nuckols went up to one of his prized Holsteins.

The gate clanged close as Matt Nuckols went up to one of his prized Holsteins.  In the past year dairy farmers in Wisconsin have had to shut down 714 farms. That’s 8.2 percent, dropping the total number of dairy farms here to 8,046. That is roughly half the number of 16 years ago.

In the past year dairy farmers in Wisconsin have had to shut down 714 farms. That’s 8.2 percent, dropping the total number of dairy farms here to 8,046. That is roughly half the number of 16 years ago. In a brief visit to Vermont Friday, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue said he did not favor a supply management system that many dairy farmers hope will help support their struggling industry.

In a brief visit to Vermont Friday, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue said he did not favor a supply management system that many dairy farmers hope will help support their struggling industry.

.png?width=554&name=chart%202018%20-3%20(2).png)

.png?width=554&name=chart%202018-2%20(2).png)

.png?width=554&name=chart%202018-1%20(2).png)

Italy’s government has come to an agreement with dairy farmers in Sardinia on the per litre price of sheep’s milk after weeks of protests over falling rates, Italian news outlets reported on Friday.

Italy’s government has come to an agreement with dairy farmers in Sardinia on the per litre price of sheep’s milk after weeks of protests over falling rates, Italian news outlets reported on Friday. Federal Member for Indi Cathy McGowan and Labor’s candidate for the seat, Eric Kerr, have clashed over milk prices.

Federal Member for Indi Cathy McGowan and Labor’s candidate for the seat, Eric Kerr, have clashed over milk prices. National Milk Producers Federation has submitted a citizen petition to the Food and Drug Administration outlining how and why the agency should use its existing regulations to guide the use of dairy terms for plant-based products.

National Milk Producers Federation has submitted a citizen petition to the Food and Drug Administration outlining how and why the agency should use its existing regulations to guide the use of dairy terms for plant-based products. AUSTRALIA’S milk production continues to lag behind 2017-18 levels, tracking almost 5 per cent lower for the current season to December.

AUSTRALIA’S milk production continues to lag behind 2017-18 levels, tracking almost 5 per cent lower for the current season to December.

Our dairy farmers are giving up in increasing numbers, and who can blame them?

Our dairy farmers are giving up in increasing numbers, and who can blame them? Dairy farming is a business. There, I said it.

Dairy farming is a business. There, I said it. Last week, Dairy Crest shocked producers and investors alike by announcing a £975m takeover by Canadian dairy giant Saputo.

Last week, Dairy Crest shocked producers and investors alike by announcing a £975m takeover by Canadian dairy giant Saputo. Nathan McGann worked out it was going to cost him about $170000 to get his 150-cow milking herd through the next seven months to spring.

Nathan McGann worked out it was going to cost him about $170000 to get his 150-cow milking herd through the next seven months to spring. The question is simple: How much longer can the average dairy farmer endure the ongoing financial crisis that the majority of dairy farmers continue to live with?

The question is simple: How much longer can the average dairy farmer endure the ongoing financial crisis that the majority of dairy farmers continue to live with?

This week Dean Foods, the nation’s largest dairy, reported steep quarterly losses. The Wall Street Journal

This week Dean Foods, the nation’s largest dairy, reported steep quarterly losses. The Wall Street Journal

Advocates for dairy farmers pressed USDA officials at a farm bill listening session to move quickly to get payments to financially strapped producers, while other groups urged the department to put a priority on removing barriers to cover crops and scheduling signups for major conservation programs.

Advocates for dairy farmers pressed USDA officials at a farm bill listening session to move quickly to get payments to financially strapped producers, while other groups urged the department to put a priority on removing barriers to cover crops and scheduling signups for major conservation programs. Our dairy farmers are giving up in increasing numbers, and who can blame them?

Our dairy farmers are giving up in increasing numbers, and who can blame them?

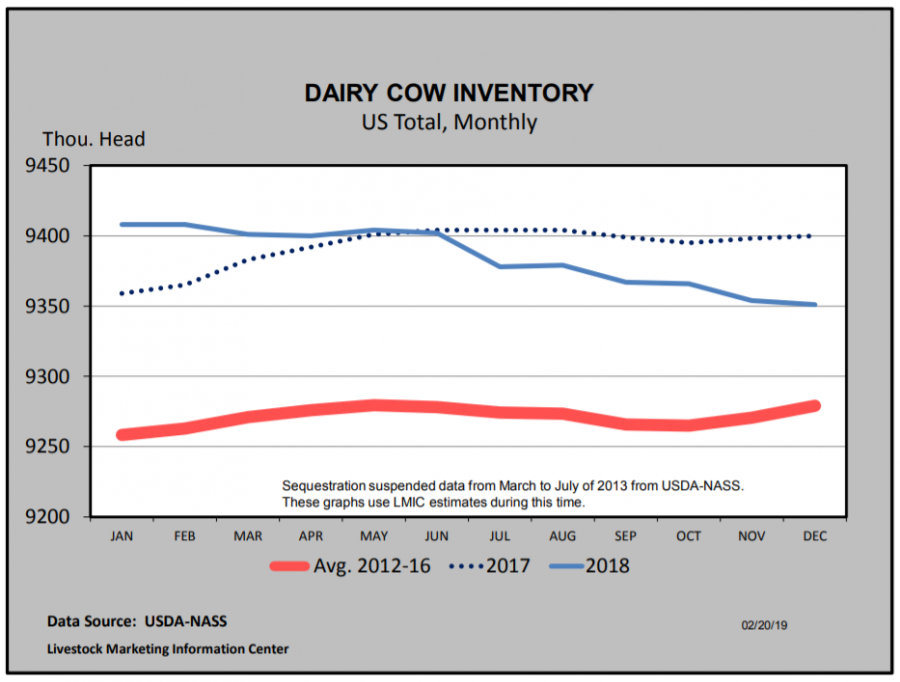

The new year hasn’t started quite so happy for U.S. dairy operators, as they enter a fifth year of significantly low prices paid for their milk.

The new year hasn’t started quite so happy for U.S. dairy operators, as they enter a fifth year of significantly low prices paid for their milk. Supermarket discounted milk was in the firing line at the Australian Dairy Conference in Canberra on Thursday.

Supermarket discounted milk was in the firing line at the Australian Dairy Conference in Canberra on Thursday.