The dairy industry’s toughness culture kept farms alive for generations. Now it’s quietly costing them six figures a year.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: If 60% of milking robots were glitching, you’d have dealers on farm by Tuesday. When 60% of farmers are burning out, we shrug and call it “part of the job.” But the research says otherwise: University of Guelph data shows 34% of farmers meet criteria for depression and 76% report moderate to high stress—and it’s showing up in bulk tanks, lameness scores, and breeding records. Canadian mastitis modeling puts subclinical cases alone at $34,344 per 100 cows annually, losses driven by the exact tasks that slip when mental bandwidth runs low: CMT testing, fresh cow checks, structured repro reviews. Farms that deliberately protect headspace are seeing results—ELBI Dairy in Manitoba cut SCC by 52% after rebuilding with robots and tighter routines. What works isn’t telling farmers to “just get help”; it’s written plans, peer groups that talk numbers and stress, and coaching designed around calving schedules. The brain making your herd decisions is equipment, too—and right now, on many operations, it’s running without a maintenance plan.

If 60% of our milking robots were glitching, you know exactly what would happen. There’d be emergency calls to the dealer, reps on the farm, and probably industry meetings asking what went wrong. When a similar share of farmers themselves are running mentally on “low‑battery,” we tend to shrug and call it “just part of the job.”

What’s interesting here is that newer research is showing this isn’t just a human‑interest story. It’s a herd‑health and profitability story. And it’s showing up in somatic cell counts, fresh cow management, reproduction, and culling decisions in ways a lot of us never fully connect back to the person in the parlor or in front of the robot screen.

Let’s walk through what the data actually says—and what it means for SCC, butterfat performance, and your bottom line in today’s cost structure.

Looking at This Mental Health Trend in Dairy

Looking at this trend over the last decade, one thing is clear: people have finally begun measuring farmer stress seriously.

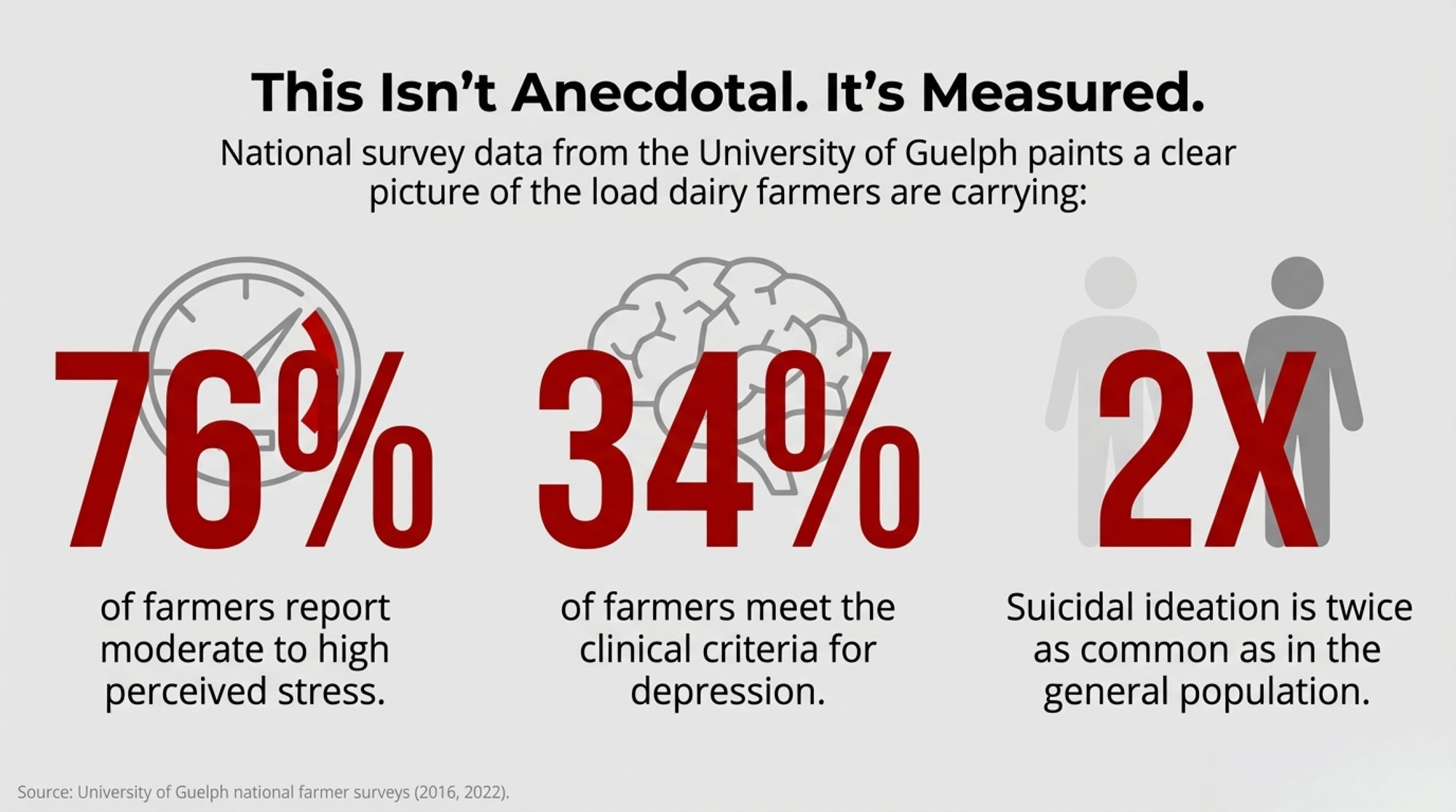

In Canada, Dr. Andria Jones‑Bitton, DVM, PhD, an epidemiologist at the University of Guelph, led a national online survey of 1,132 farmers between 2015 and 2016 using validated scales for stress, anxiety, depression, and resilience. The results were stark:

- About 34% of farmers met the criteria for depression.

- Roughly 57% and 33% met criteria for possible and probable anxiety, respectively.

Farmers scored significantly worse than normative Canadian population values across stress, anxiety, depression, and resilience, confirming what many of us have felt anecdotally for years.

Later, the same research team examined farm families, including both parents and adolescents. Follow‑up work on farm families and youth in agriculture reported that around 60% of adults and teens in farm households were experiencing at least mild symptoms of depression, raising concern that stress is impacting the whole family, not just the primary operator.

Then COVID hit. A national follow‑up survey of Canadian farmers conducted in 2021 and published in 2022 found that 76% of farmers reported moderate to high perceived stress, and suicidal ideation was about twice as common as in the general Canadian population.

University of Guelph summarized that work by noting that roughly one in four farmers had experienced suicidal thoughts in the previous 12 months.

And it’s not just a Canadian story. A 2022 HillNotes analysis and coverage in Hoard’s Dairyman highlight that farmers in several U.S. regions are also at greater risk of mental‑health challenges and suicide than many other occupations, with financial stress and fear of losing the farm topping their list of stressors. In Pennsylvania and across the Upper Midwest, extension and farm bureau surveys have flagged similar patterns. Recent European research has found comparable trends, with farmers scoring higher on stress and burnout measures than general working populations.

What I’ve noticed, and what the qualitative work confirms, is a consistent pattern in how farmers talk about this. In interviews with Ontario producers, Jones‑Bitton’s team heard farmers say things like “farmers aren’t into the emotions and things” and describe mental‑health struggles as “just part of farming,” while still labelling their own mental health as “good” or “fine” even when they screened as depressed or anxious.

That toughness has kept a lot of farms alive through years that would have sunk other businesses. But this development suggests that early warning signs are often normalized rather than treated as something that deserves a plan, just like any other high‑risk area of the operation.

What Depression Really Changes in Day‑to‑Day Dairy Management

So what’s actually going on in the brain when chronic stress or depression sets in?

Modern psychology research shows that depression changes how people evaluate mental effort: planning, concentrating, and making decisions feel more costly, even when your body is still capable of hard physical work. Farmers in Canadian and international studies describe low energy, difficulty focusing, trouble making decisions, and feeling “foggy” or “overloaded.”

On a dairy, you can see that pattern pretty clearly.

You can still:

- Milk two or three times a day.

- Push feed, scrape alleys, and keep the dry lot reasonably in shape.

- Fix the broken gate or that leaky waterer in the holding area.

But the “thinking jobs” start to slide:

- “I’ll pull those SCC reports tomorrow.”

- “I should CMT those fresh cows, but I’ll get to it later this week.”

- “I’ll sit down with the breeding and culling records when things slow down.”

| Task Category | What Still Happens (Physical/Routine) | What Quietly Slips (Cognitive/Planning) |

|---|---|---|

| Milking & Feeding | Milk 2-3x daily, push feed, scrape alleys | Structured SCC trend analysis, CMT testing on fresh cows |

| Facilities | Fix broken gates, leaky waterers | Lameness scoring on schedule, body condition scoring |

| Reproduction | AI techs still show up | Heat detection without activity monitors, structured repro reviews |

| Fresh Cows | Fresh cows still get fed and milked | Subclinical ketosis checks, rumination monitoring, “just off” cow follow-up |

| Culling & Economics | Obviously sick cows still leave | Data-driven cull reviews, borderline cow decisions, cost-benefit modeling |

What’s interesting is that we now have herd‑level data to back up what many of us have seen. An exploratory study on Ontario dairy farms using robotic milking systems measured farmers’ mental health using validated scales and then linked those scores with cow health and welfare indicators.

The researchers found that:

- Higher farmer stress scores were associated with a higher prevalence of severe lameness.

- Anxiety and depression scores were higher among farmers who worked mostly alone, fed manually, or had lower milk protein percentages.

- Resilience scores were higher on farms using automated feeding systems, suggesting potential benefits in terms of mental bandwidth and consistency.

Dairy Global summarized the work, stating that farmer and cow well-being are clearly connected, and that automation and better support can reduce stress and improve both lameness and overall performance.

On farm, as many of us have seen across Ontario free‑stalls, Wisconsin parlors, Quebec tie‑stalls, and Western dry lot systems, the same vulnerable tasks tend to pop up:

- Subclinical mastitis detection: routine CMT testing on fresh cows, tracking SCC trends, and acting on borderline cows.

- Heat detection and recording, especially in non‑robot herds without activity monitors.

- Fresh cow management in the transition period: spotting subclinical ketosis, watching intakes and rumination, and checking cows that are just “off.”

- Lameness and body condition scoring are done on a schedule, not just when a cow is obviously sore.

- Structured repro and cull reviews with numbers on the table instead of relying only on gut feel.

Those jobs are exactly where the money is quietly made—or quietly lost.

The Math of Mental Load: Where the Money Disappears

Farmers tend to ask, “What’s this really worth?” So let’s talk big math using actual research and common economic assumptions for today’s input and replacement costs.

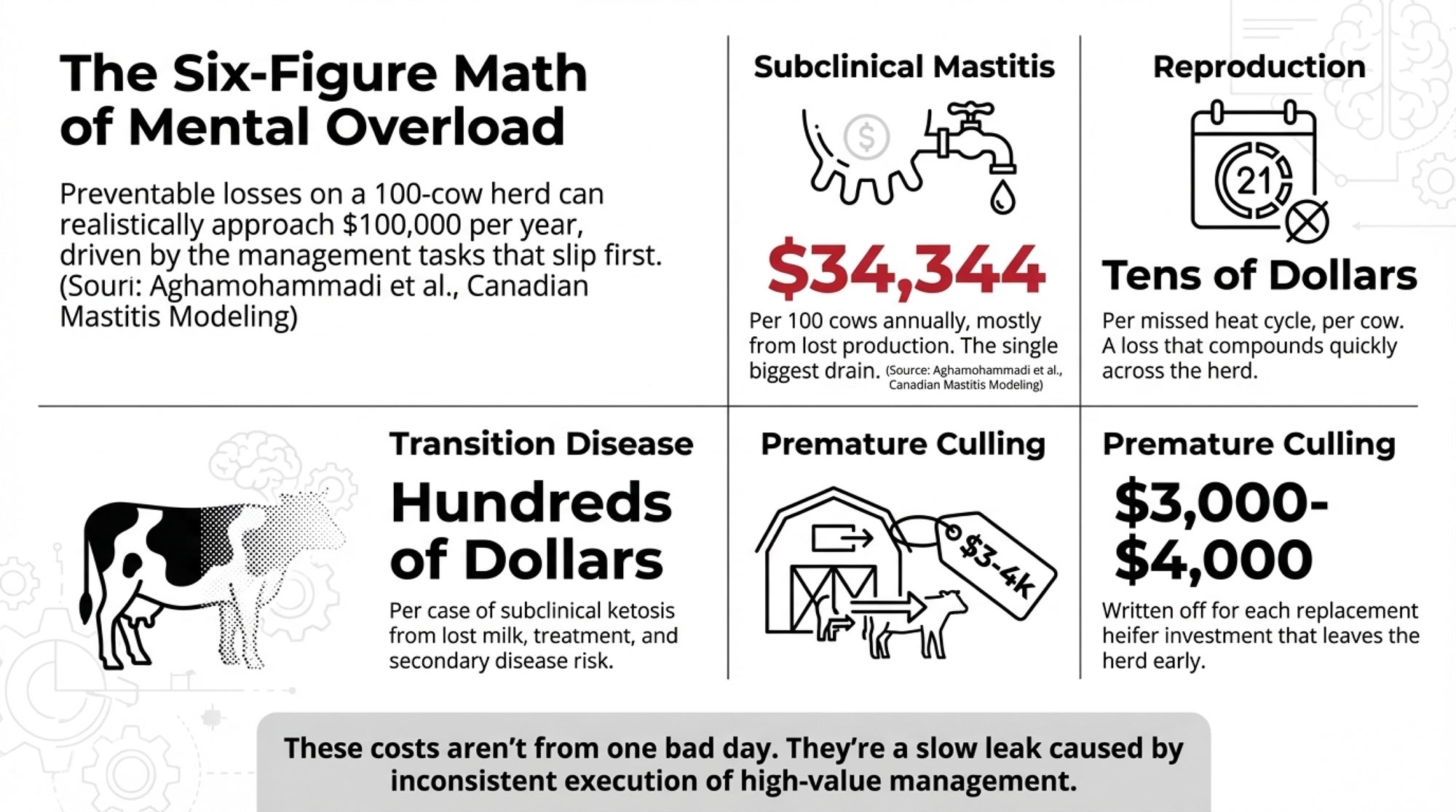

A Canadian team led by Dr. Ebrahim Aghamohammadi modeled herd‑level mastitis‑associated costs on Canadian dairy farms using detailed production and health data combined with economic modeling. They estimated that:

- Median total mastitis cost was 662 CAD per milking cow per year.

- About 48% of mastitis costs were due to subclinical mastitis (SCM)—cases that often only show up on SCC reports or CMT testing.

- In their model, SCM cost around 34,344 CAD per 100 cow‑years, compared with about 13,487 CAD per 100 cow‑years for clinical mastitis.

They also showed that milk yield reduction was the largest single cost component, especially in subclinical cases. Most of the cost is in lost production, not just treatment and discarded milk.

Now, stack reproduction on top. Many dairy economists and extension bulletins peg the cost of an extra day open at several dollars per cow per day, once you factor in delayed calving, reduced lifetime milk production, and higher culling risk. Depending on milk price and stage of lactation, missing a heat on one cow can easily represent tens of dollars per 21‑day cycle, especially when it repeats or involves multiple cows.

Subclinical ketosis is another slow drain. Transition‑cow economic work commonly estimates the cost of each subclinical ketosis case at around the low hundreds of dollars, once early‑lactation milk loss, a higher risk of displaced abomasum and metritis, and poorer fertility are included.

Then there’s premature culling. With 2024–2025 feed, labor, and construction costs where they are, it’s increasingly common to see full replacement heifer rearing costs in the 3,000–4,000 dollar range per heifer by first calving, depending on region and system. Every cow that leaves the herd early because her issues weren’t caught and resolved is a partial or complete write‑off of that investment.

So on a 100‑cow herd, even at conservative assumptions for:

- Subclinical mastitis losses (~34,000 CAD per year),

- Extra days open from missed heats,

- A handful of subclinical ketosis cases, and

- A few premature culls,

It’s realistic to expect preventable losses in the neighbourhood of 100,000 CAD per year due to the inconsistent execution of these management tasks.

That’s not a single study’s number; it’s a composite built from peer‑reviewed mastitis data, typical reproduction and transition‑disease economics, and current replacement values.

What I’ve noticed on real farms is that the tasks that control those costs—structured SCC work, tight fresh cow management, disciplined repro and culling reviews—are exactly the jobs that require the most sustained mental effortfrom the key decision‑maker.

That’s where mental overload stops being a personal issue and becomes a line item.

What Happens When You Free Up Headspace: A Manitoba Example

It’s one thing to lay out models and surveys. It hits differently when you watch a real farm go through the change.

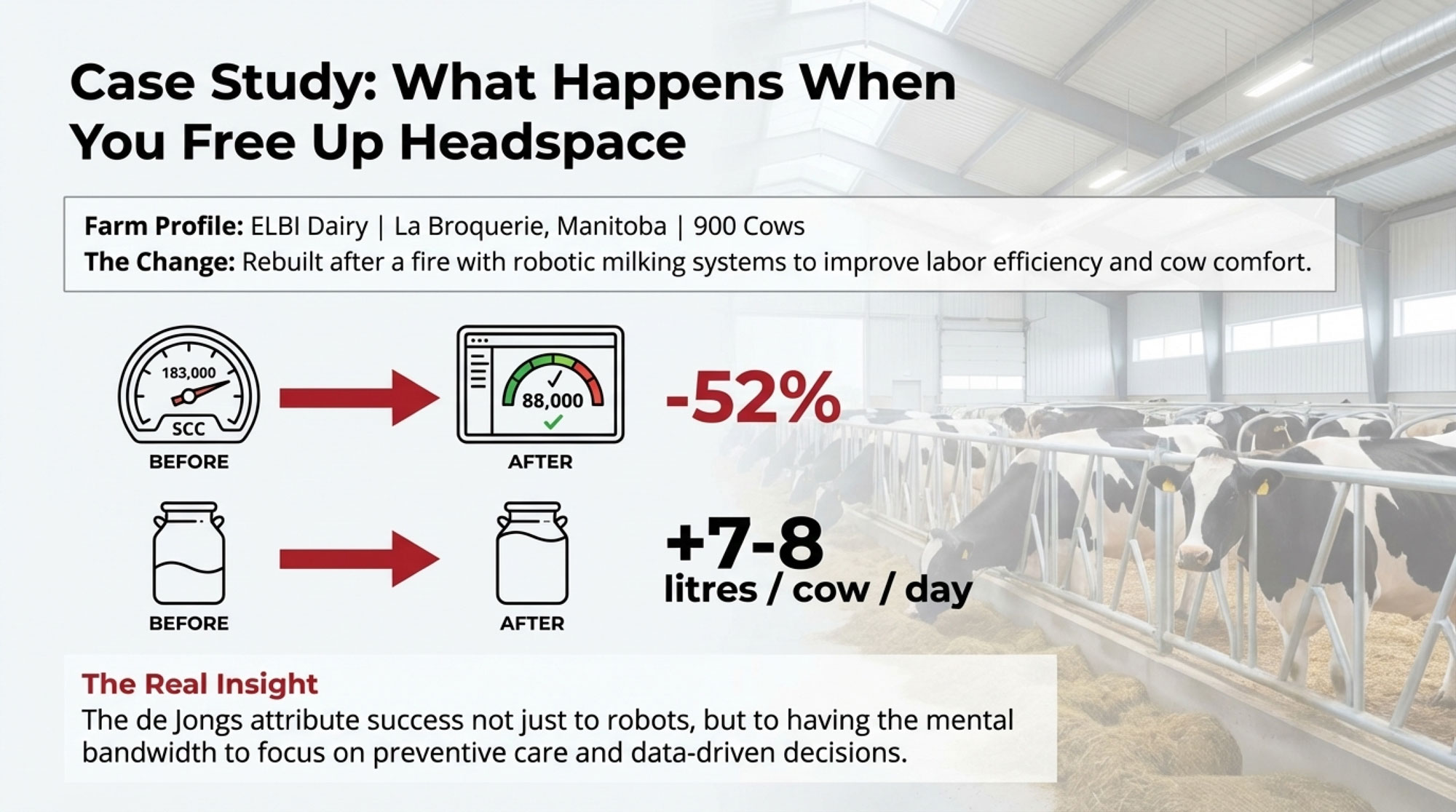

ELBI Dairy in La Broquerie, Manitoba, is a family‑run operation milking roughly 900 cows, and they’ve become a bit of a case study in how automation and mental bandwidth can interact. After a barn fire, the de Jong family rebuilt with robotic milking systems and a barn designed for labor efficiency and cow comfort. Their journey has been featured in the Lely case material.

| Performance Metric | Before Robots (Conventional) | After Robots + Optimized Routines | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Tank SCC | 183,000 cells/mL | 88,000 cells/mL | -52% |

| Milk Yield per Cow per Day | ~32 L/day (~70 lb/day) | ~40 L/day (~87 lb/day) | +25% |

| Hoof Health & Lameness | Conventional levels (moderate issues) | Substantially improved, lower hoof costs | Major improvement |

| Farmer Mental Bandwidth | High stress, long hours, physically demanding | More time for data review, fresh cow management, strategic decisions | Freed up |

Before robots, ELBI was milking conventionally and reported:

- Bulk tank SCC around 183,000 cells/mL.

After they transitioned to robots and settled into the new routines:

- SCC dropped to around 88,000 cells/mL—about a 52% reduction.

- Milk yield increased by around 7–8 litres per cow per day (roughly 15–17 lb/cow/day).

- They saw large improvements in hoof health and substantially reduced hoof‑related costs once they optimized manure handling, cow flow, and stall use.

In interviews, the de Jongs don’t talk like robots magically cured their mastitis and lameness. They talk about improved cow flow, more consistent routines, and the ability to devote more attention to fresh cow management, preventive care, and data‑driven decision‑making because the daily milking grind was less physically and mentally draining.

That fits almost exactly with the Ontario robotic‑milking research: lower stress and higher resilience on farms with more automation and support, and better lameness and welfare outcomes when farmers are in a better mental place.

Now, full automation isn’t going to pencil out for every farm. A 70‑cow tie‑stall in Quebec, a 300‑cow sand‑bedded freestall in Wisconsin, and a 1,500‑cow dry lot in California are all playing different capital and labor games.

But I’ve seen similar patterns when farms:

- Hire or grow a herdsman/assistant manager role.

- Lean into herd management software and actually use the reports.

- Reorganize chores so the primary decision‑maker isn’t also doing every repetitive task.

The theme is the same: when you deliberately free up mental bandwidth for the people steering the ship, the herd typically responds, and so does the milk cheque.

Why “Just Get Help” Doesn’t Really Move the Needle

With numbers like these, it’s fair to ask: if the stakes are this high, why don’t more farmers just reach out and say, “I need help”?

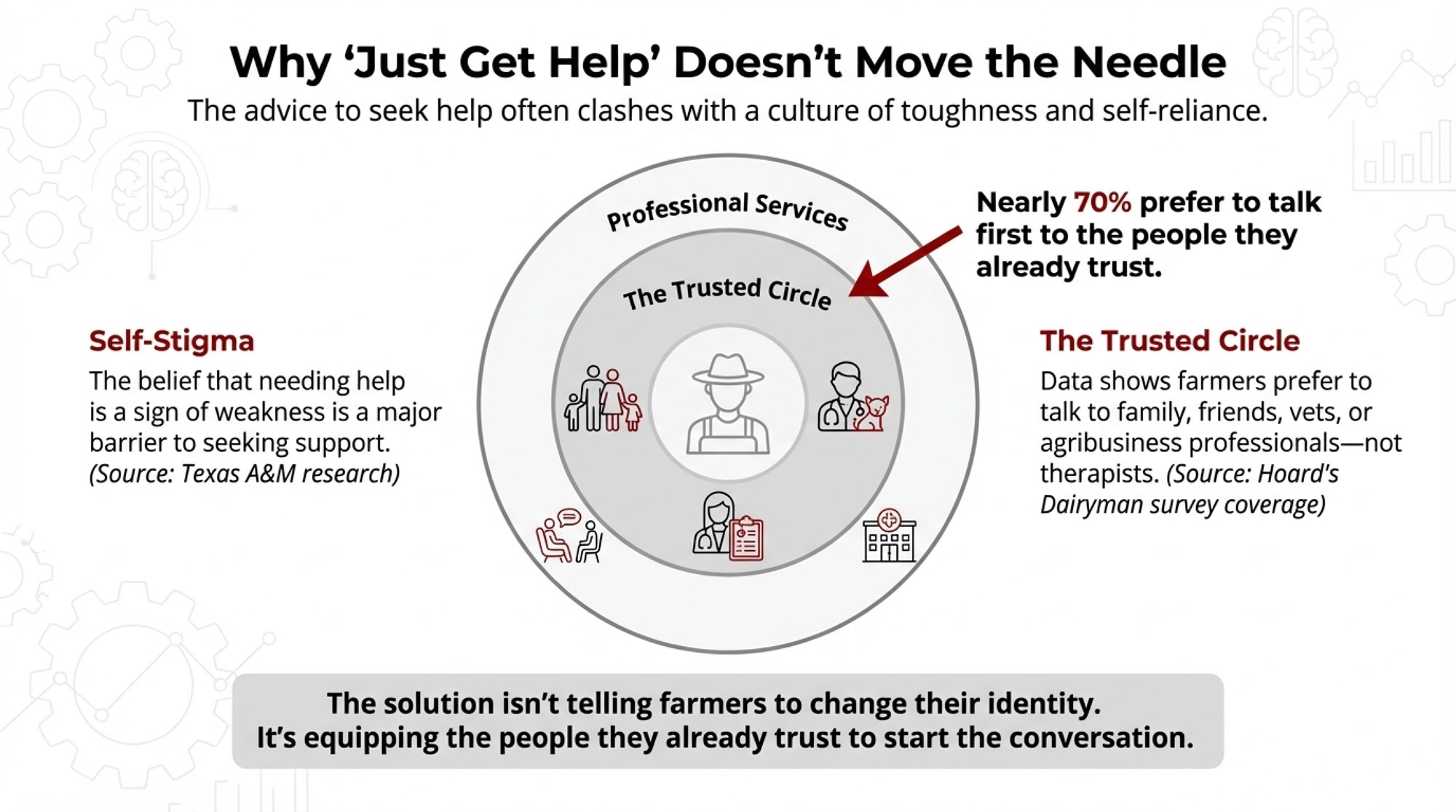

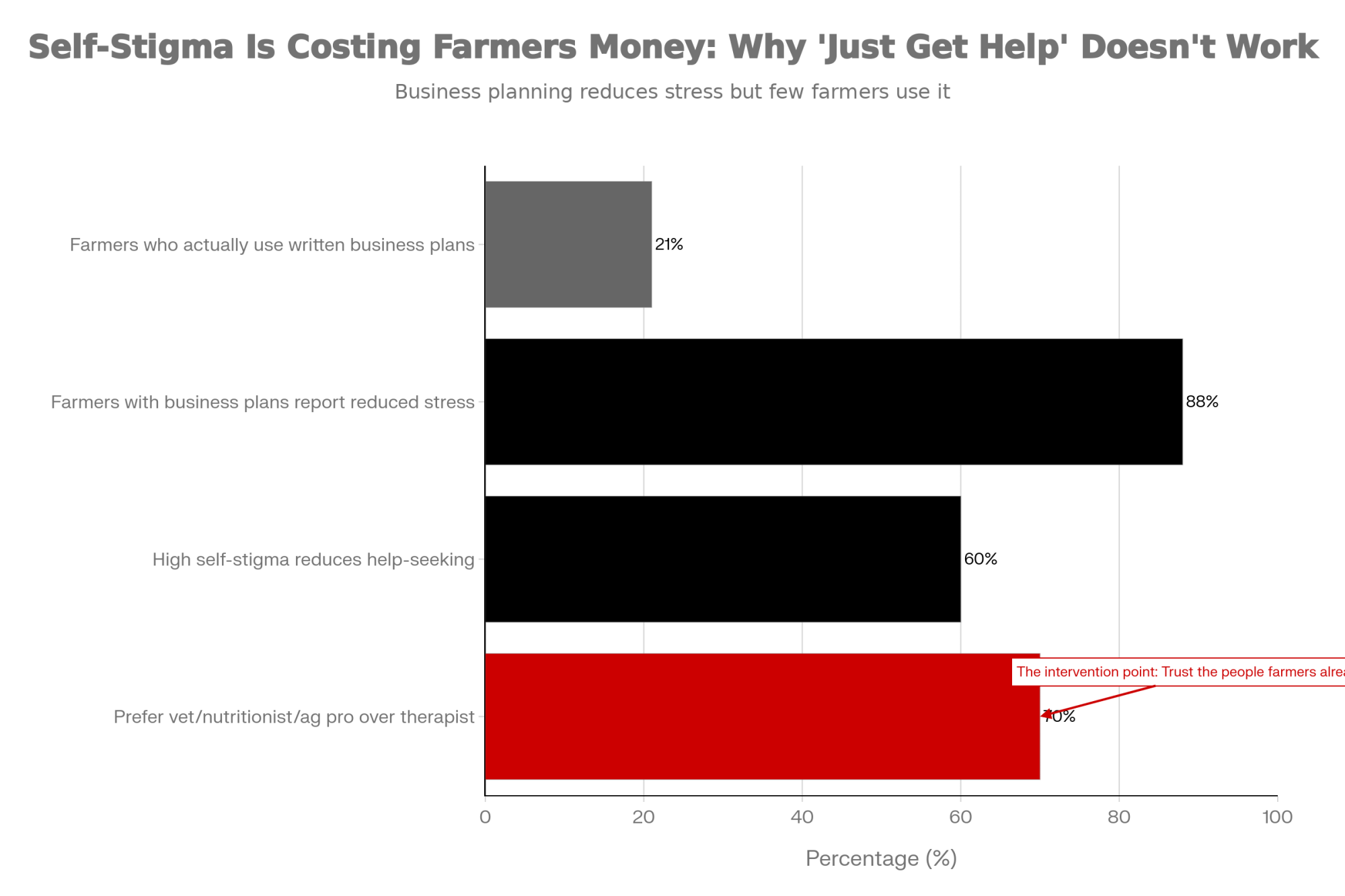

A Texas‑based study tackled that question. Researchers surveyed 429 agricultural producers and looked at factors that influenced whether they said they’d seek help for mental‑health concerns. One of the strongest predictors was self‑stigma—the belief that needing help means you’re weak or a failure.

Producers with higher self‑stigma were significantly less likely to say they’d seek help, even when their symptom scores were high.

Qualitative work with Canadian farmers turned up similar themes. In interviews, farmers talked about not wanting to be seen as weak, about feeling they “should be able to handle it,” and about worrying what neighbours or lenders might think if they sought professional help.

Hoard’s Dairyman reported that in one survey, nearly 70% of farmers said mental health was very important to them, but still preferred to talk first to family, friends, vets, or agribusiness professionals rather than to therapists or doctors.

That’s a big clue. It suggests that simply telling farmers “you should prioritize your mental health” doesn’t land because it clashes with identity and habit.

From an economic standpoint, that reluctance becomes a risk factor. When self‑stigma stops people from using tools that would protect their cognitive capacity, it’s not just their mood that takes a hit—it’s mastitis control, transition performance, reproduction, and culling decisions that suffer along with it.

So if “just get help” doesn’t fit how many farmers see themselves, what does?

What Farmers Are Finding Actually Works

What farmers are finding, across different regions and systems, is that the approaches that gain traction don’t start with mental‑health labels. They start with better management, reduced risk, and clearer plans—and mental‑health improvements show up as part of that package.

| Intervention Type | Specific Tool/Approach | Research-Backed Outcome | Implementation Barrier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business Planning | Written business plan, reviewed quarterly | 88% report reduced stress & peace of mind (Farm Management Canada) | Only 21% currently use one |

| Peer Support | Dairy discussion groups (benchmarking + candid talk) | 96% discuss safety/health; normalize challenges (Irish study) | Requires regular time commitment |

| Flexible Coaching | Phone-based coaching around farm schedule | Significant reduction in depression & stress scores (German RCT) | Low—phone-based, no clinic visit |

| Financial Literacy | Understanding disaster assistance, government programs | Reduces feeling trapped; improves decision confidence (U. Georgia) | Requires trusted advisor to explain |

| Automation/Support | Hire herdsman, use herd software, automate feeding | Higher resilience, lower stress, better lameness scores (Ontario study) | Capital or labor cost |

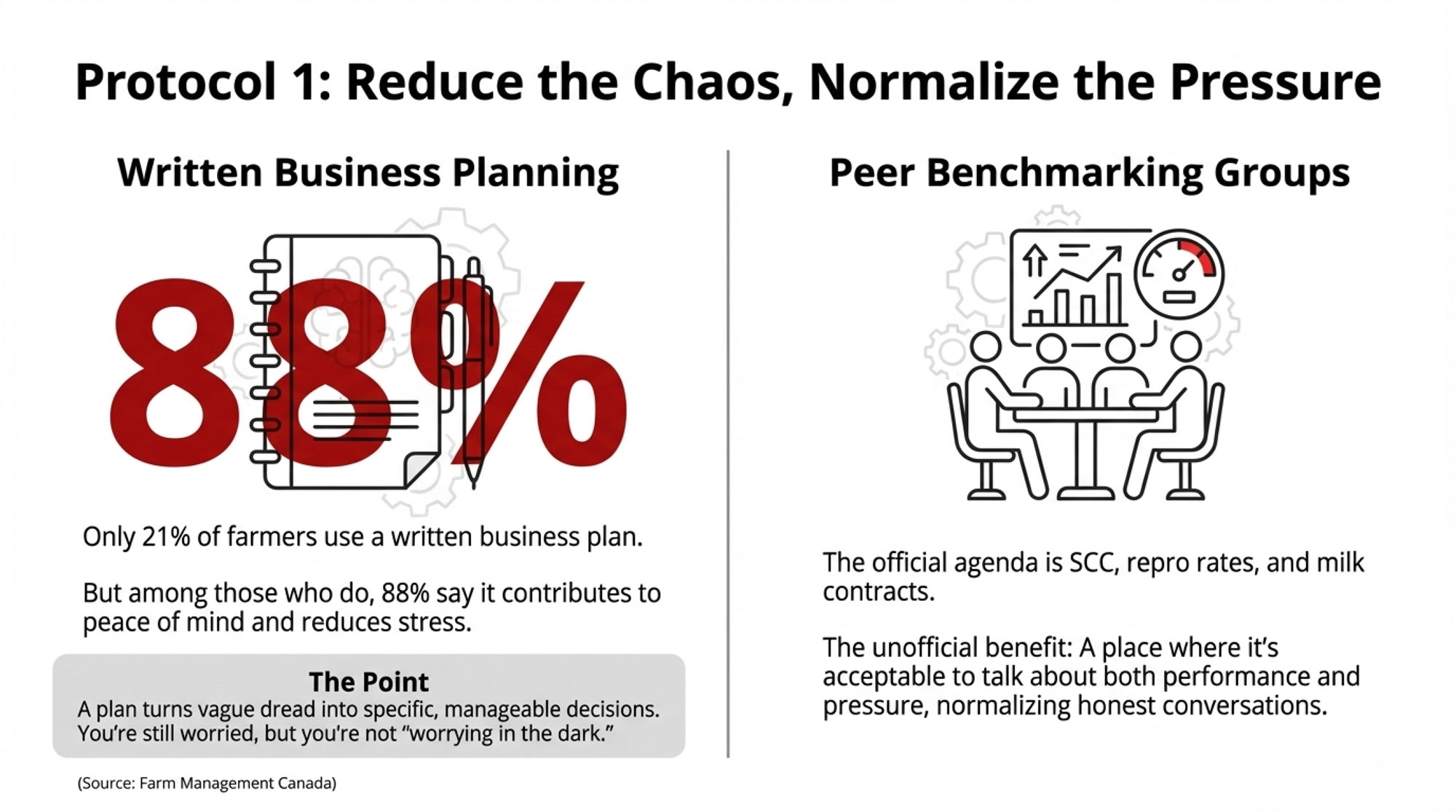

1. Business Planning as Headspace Protection

Farm Management Canada’s “Exploring the Connection between Mental Health and Farm Business Management” project looked squarely at how business practices and mental health interact. One key finding:

- Only about 21% of farmers reported regularly using a written business plan.

- Among those, 88% said the plan contributed to peace of mind and reduced stress.

Canadian Cattlemen’s summary of that work highlighted that farmers with business plans were more likely to review financial statements regularly, work with advisory teams, and take at least some time away from the farm.

The data suggests that planning doesn’t magically eliminate stress, but it reduces background chaos, freeing up mental energy for fresh cow checks, repro and culling decisions, and watching component performance rather than just reacting to emergencies.

On mid‑size Ontario and Prairie farms I’ve talked with, I often hear: “I still worry. But I’m not worrying in the dark anymore.”

2. Peer Groups That Talk Numbers—and What’s Behind the Numbers

In Ireland, dairy discussion groups are a backbone of extension. Studies of those groups found that around 96% of them discuss occupational safety and health, and about 89% have participants share personal accident or illness experiences.

The official agenda is grazing, breeding, milk contracts, and policy. The reality is that they also become spaces where someone says, “Last spring nearly finished me,” and people around the table understand exactly what that means economically and emotionally.

In the U.S. Midwest and across Canadian provinces, dairy benchmarking and discussion groups run by extension, co‑ops, and private consultants play a similar role. Farmers come to compare SCC, butterfat, days in milk, pregnancy rate, and transition metrics.

Over time, those meetings often become places where it’s acceptable to talk about both performance and pressure.

These groups don’t require anyone to say, “I’m here for mental‑health support.” They simply normalize honest conversation about what it takes to keep a herd and a family going.

3. Coaching Designed Around Real Farm Schedules

A randomized controlled trial in Germany tested telephone‑based coaching for farmers and foresters. Over six months, the group receiving structured coaching calls—focused on coping strategies, problem‑solving, and planning—saw significantly larger reductions in depression and stress scores compared with the control group.

The format is tailor‑made for agriculture:

- Calls happen by phone.

- Sessions are scheduled around farm work.

- The service is framed as coaching rather than traditional therapy.

An evidence‑based guide for delivering mental‑healthcare services in farming communities, published in 2024, emphasized that flexible, phone‑ or online‑based services that respect farm schedules and culture are more likely to succeed than clinic‑only models.

We’re starting to see that in practice in places like Canada, where agricultural organizations and the Canadian Centre for Agricultural Wellbeing are rolling out farm‑specific support lines and coaching‑style services.

4. Financial Literacy as a Pressure Relief Valve

At the University of Georgia, extension staff surveyed 310 farmers about which financial education topics would most help reduce their stress. The top priorities weren’t exotic hedging strategies; they were very practical:

- Understanding disaster assistance programs.

- Knowing what government financial support options exist and how to access them.

Social worker and agricultural educator Dr. Anna Scheyett, who has been a key voice in this work, has argued that solid financial literacy and access to trustworthy information are themselves mental‑health tools for farmers.

They don’t fix milk price or weather—2024–2025 is still volatile on both fronts—but they keep producers from feeling trapped or blindsided.

Who’s Actually in the Best Position to Start the Conversation?

These kinds of changes don’t just appear out of thin air on a farm. Someone has to open the door. And as many of us have seen, it makes a huge difference who that person is.

The Front Line: Vets and Nutritionists

Your veterinarian and your nutritionist probably know more about your cows and your numbers than anyone outside the family. They also see you regularly.

A Canadian review on mental‑health supports for farmers noted that vets and other ag professionals are often the first to notice when a farmer is struggling, and that equipping them with basic knowledge and referral pathways is a practical way to get help started.

Some vet practices and feed companies are now giving their teams simple tools and phrases, like:

- “We’ve built a good plan to get this mastitis flare‑up under control. How are you doing with everything else on your plate right now?”

- “Between herd health, markets, and family, you’re carrying a lot. Would it help if we brought your accountant or lender into this conversation so we can put a full plan on paper?”

Because that comes from someone you already trust with your herd’s health and ration, it often opens the door more effectively than a generic “take care of yourself” message.

Spouses and Family

On family farms, spouses, parents, and older kids often see the changes first—late‑night screen time, staying in the barn longer than usual, snapping over little things.

Research on farmer burnout and stress highlights spousal and family support as one of the strongest protective factors. The conversations that work best usually start from what’s been noticed:

- “I’ve noticed you’re really quiet lately.”

- “You’re up late every night looking at the books, and I’m worried about how much you’re carrying.”

That’s not a weakness. That’s good family‑level management of a high‑risk business.

Lenders and Advisors

In both Canada and the U.S., some ag lenders and advisory firms have taken training on farm stress and mental‑health awareness. It makes sense: they’re in the room when some of the hardest decisions get made—refinancing, expansion, downsizing, or succession.

A good lender or advisor can say, “We’ve seen other farms face this kind of squeeze. There are financial tools we can look at. And if the stress side of this is starting to get heavy, there are people we can connect you with who understand agriculture.”

Given the evidence that chronic stress undermines decision quality and increases risk, that’s not overstepping. It’s risk management for both the farm and the lender.

Building a “Transition Protocol” for Farmers, Not Just Cows

Most of us already treat the transition period for cows as a high‑risk window that deserves its own protocol: close‑up and fresh cow rations, stocking density targets, bedding management, and daily fresh cow checks.

It’s worth asking: what’s the equivalent for the people?

In northern regions like Ontario, the Prairies, and the Upper Midwest, farmer “transition risk” often runs from late fall through winter:

- Short days and limited sunlight.

- Long stretches inside barns and shops.

- Cold stress on cows and humans.

- Year‑end bills, tax planning, and sometimes weaker milk prices.

On pasture‑based, spring‑calving herds in places like Ireland or New Zealand, the crunch might be calving plus breeding. In large Western dry lot systems, it can be summer heat and water uncertainty. Every region has its own hot zone.

What I’ve noticed is that more operations are starting to deliberately build farmer‑focused steps into their seasonal management plan, right alongside herd protocols:

Light and sleep routines: In higher‑latitude regions, using a 10,000‑lux light box at breakfast for 20–30 minutes, combined with making a point of getting outside in real daylight, aligns with clinical guidance for seasonal mood support. Canadian farmer research has found that coping strategies, including getting outside and staying physically active, are commonly used and can help manage stress.

Written winter game plan: Sitting down in October or November with your accountant, nutritionist, or business advisor to map out winter cash flow, feed inventory, and “if this, then that” scenarios helps turn vague dread into specific, manageable decisions.

One trusted peer: Picking one other producer—a neighbour, co‑op contact, or discussion‑group colleague—and agreeing to a weekly check‑in with one win, one frustration, and one thing you’re watching. It doesn’t take long, but it keeps isolation from sneaking up on you.

Pre‑booked off‑farm touchpoints: Registering ahead for winter workshops, show‑season meetings, or benchmarking sessions makes it more likely you’ll actually get off the farm at least occasionally. Surveys and commentary from extension and industry consistently show that farmers who engage in these events feel more supported and more confident in their decisions.

Checklist‑style management tasks: Turning “stay on top of herd health” into specific, visible tasks—”Monday: CMT fresh cows; Wednesday: lameness score high group; Friday: review repro and cull list”—and putting them on a whiteboard or in your phone takes some load off your memory on the rough days.

None of this requires anyone to say, “I’m depressed.” It just treats your attention and decision‑making capacity as another critical resource, right alongside cow comfort, forage quality, and parlor performance.

Where Farmers Can Turn: Practical Resources

Looking at this trend, one encouraging development is the growth of farm‑specific support programs that understand both the business and the culture.

In Canada, the Canadian Centre for Agricultural Wellbeing has been involved in launching the National Farmer Wellness Network, a crisis‑line‑style resource that connects farmers with trained agricultural responders. Programs like “In the Know,” a mental‑health literacy workshop designed specifically for farmers and farm advisors, are offered by universities and ag organizations to give people a common language and basic tools to support one another.

In the United States, several states have farm‑stress hotlines and online resources housed in departments of agriculture, extension services, and farm bureaus. Farmers are more likely to engage with resources promoted through trusted ag channels that respect farm schedules and realities.

Internationally, programs like Farmstrong in New Zealand and resources from the National Centre for Farmer Health in Australia combine practical farm management content with wellbeing tools, using farmer stories, videos, and events to make the topic relatable.

The common thread is that these supports are built around how farms actually operate—early mornings, long days, seasonal crunches, family involvement—not around generic 9‑to‑5 models.

The Bottom Line

At this point, it’s hard to argue that farmer mental health is just a “soft” issue. The evidence is pretty clear:

- Farmers are carrying higher loads of stress, anxiety, depression, and burnout than the general population.

- Poor mental health can negatively affect decision‑making, cow health, productivity, and overall farm performance.

That means this isn’t just a wellness story. It’s a story about dairy herd management and profitability.

If you’re looking at your own operation and wondering what to actually do, here are a few concrete next moves that many progressive herds are finding helpful:

- Put a simple, written plan in place. Even a basic winter business plan and a short list of key herd‑health tasks on a whiteboard can take a surprising amount of weight off your mind.

- Turn key health and repro jobs into checklists. Don’t leave CMT testing, lameness scoring, and cull reviews to “when I get time.” Make them scheduled, visible jobs.

- Find or build a peer group that talks about both numbers and stress. Whether it’s an extension discussion group, a virtual benchmarking circle, or a coffee‑shop crew, having at least one space where you can talk honestly about both performance and pressure pays dividends.

- Identify one trusted professional you’d talk to if the load gets too heavy. That might be your vet, nutritionist, lender, or advisor. Decide ahead of time whom you’d call, just like you know whom you’d call if a main line in the parlor blew out.

- Explore the resources available in your region. That might be a farmer wellness line, an “In the Know” workshop, a state farm‑stress program, or a coaching service that understands agriculture.

The culture of toughness has a proud place in dairy’s history. It’s part of why this industry is still standing after price crashes, policy shocks, and brutal weather years. But when that same toughness keeps us from using tools that protect our ability to think clearly and manage well, it’s quietly expensive.

If 60% of the milking systems in Wisconsin, Quebec, or California were underperforming because of a design flaw, the industry would throw everything it had at the problem—service, training, support, maybe even recalls. When a similar share of the people running those systems are stretched past their limits, and we know that’s affecting mastitis control, fresh cow management, repro, and culling decisions, it deserves the same level of attention.

The good news is we don’t have to choose between being tough and being smart. We can keep the grit this business demands and still take care of the one piece of equipment no dairy can afford to burn out:

The brain that decides when to test that fresh cow, when to call the vet, when to tweak that ration, when to cull, when to invest—and, just as importantly, when to rest.

If you’d overhaul your robot or your parlor for a 10% SCC reduction, it might be time to give the same attention to the operator between your ears.

From what I’ve seen—and what the data backs up—when farms start treating that as part of their herd management plan, the cows notice. The milk cheque notices. And the people around your kitchen table notice too.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Mental load is a profit issue, not a wellness issue: 34% of farmers meet depression criteria and 76% report high stress—and it’s showing up in bulk tanks, lameness scores, and breeding records

- The six-figure math hiding in plain sight: Subclinical mastitis alone costs ~$34,000 per 100 cows annually. Stack reproduction losses, transition disease, and premature culls, and you’re looking at $100,000/year in preventable drag on a 100-cow herd

- Freeing up headspace delivers measurable ROI: ELBI Dairy cut SCC by 52% after rebuilding with robots. No robot budget? Farms see similar gains from hiring a herdsman, actually using herd software, or reorganizing who handles the “thinking jobs.”

- Forget “just get help”—meet farmers where they are: 70% would rather talk to a vet, nutritionist, or lender than a therapist. The real play is equipping those trusted advisors to open the door

- Your playbook: Write a winter business plan. Turn fresh cow checks into visible checklists. Find one peer for weekly check-ins. Decide now who you’d call before you need to

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- 83% of Dairies Overtreat Mastitis – That’s $6,500/Year Walking Out the Door – You’ll gain a surgical protocol for mastitis that stops the profit bleed from unnecessary discards. This breakdown exposes how “decision-driven” variation triples treatment costs and arms you with the specific benchmarks to capture $6,500 in immediate annual savings.

- 211,000 More Dairy Cows. Bleeding Margins. The 2026 Math That Won’t Wait. – Position your operation for the structural reset coming this year. This analysis reveals why the 20-year heifer inventory low and beef-on-dairy premiums have broken traditional culling math, delivering a strategic playbook to protect your equity before margins compress further.

- Dairy Tech ROI: The Questions That Separate $50K Wins from $200K Mistakes – Avoid the “shiny ornament” trap with a brutal reality check on automation. This guide delivers the unconventional infrastructure requirements often ignored by vendors, ensuring you hit the 15% ROI target by matching specific technology to your operation’s actual scale.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!