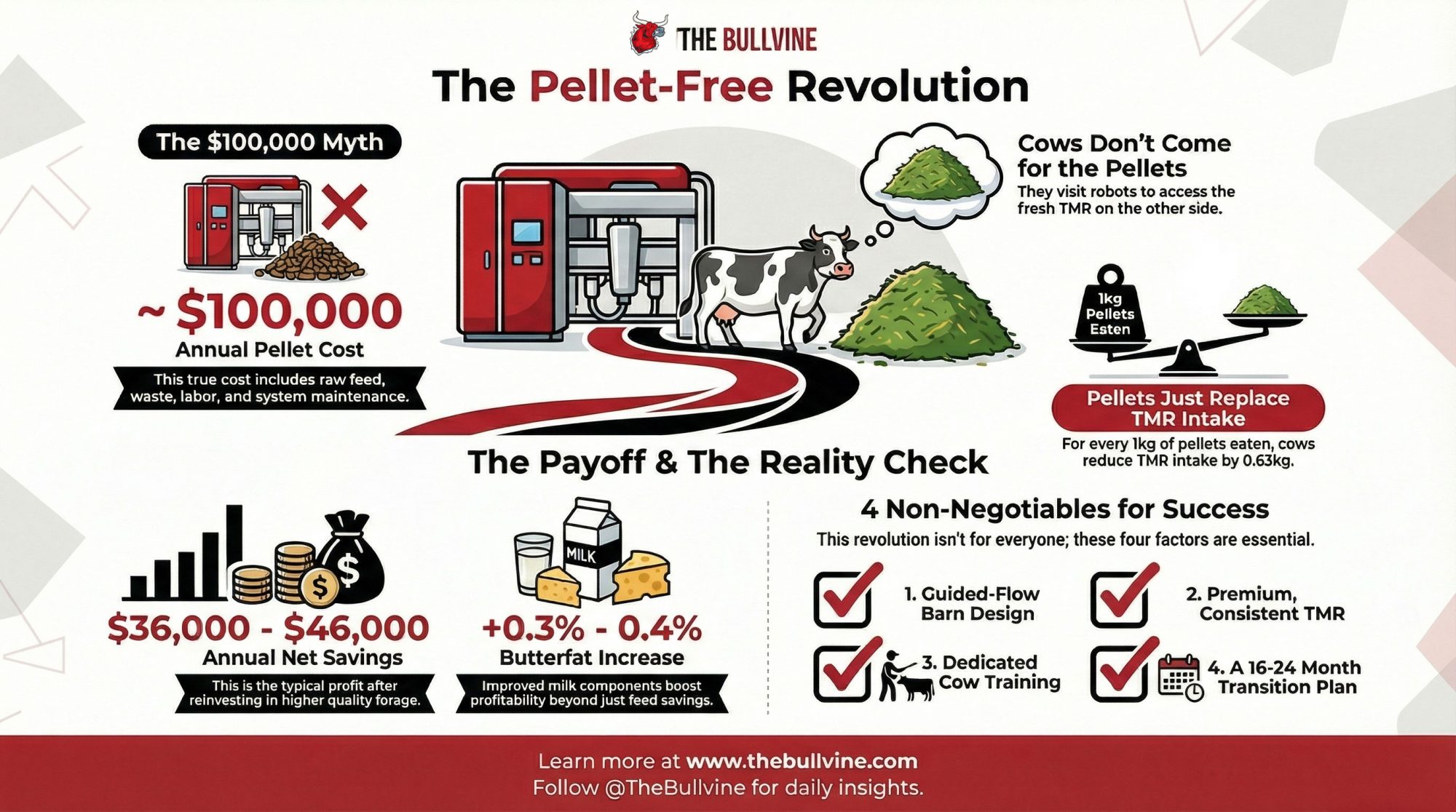

Plot twist: Your cows visit robots for the TMR behind them, not the pellets. This mistake costs $100K/year.

Executive Summary: What if the dairy industry has been wrong about robot pellets for 25 years? Growing evidence from 75+ farms across Wisconsin and Ontario shows that eliminating pellets entirely saves $36,000-46,000 annually while improving butterfat by 0.3-0.4%—with no long-term production loss. University research from Saskatchewan, Wisconsin, and Guelph confirms these pioneers’ discovery: cows visit robots to access fresh TMR beyond them, not for the pellets, making that $100,000 annual expense unnecessary. But here’s the reality check: success requires guided-flow infrastructure (not free-flow), premium forage quality, dedicated management, and the financial capacity to weather 10-15% production drops during a difficult 16-24 month transition. This revolution isn’t for everyone—operations with fewer than 200 cows or limited finances should proceed cautiously. What makes this story remarkable isn’t just the economics; it’s proof that some of agriculture’s most expensive assumptions have never been properly questioned.

You know, for more than two decades, those of us investing in robotic milking systems have accepted one fundamental truth: feeding pellets to the robot is essential to motivate voluntary cow visits. Equipment manufacturers designed for it. Nutritionists built entire programs around it. We all budgeted for it without question. But here’s what’s interesting—what if this core assumption, built into thousands of robotic dairy operations worldwide, turned out to be optional?

That’s exactly what a growing number of progressive dairy farmers are discovering. By eliminating feed pellets entirely from their robotic milking systems, operations from California to Wisconsin are reporting annual savings of $36,000–$46,000 per 200 cows, improved milk components, and simplified management—all while maintaining or even increasing production. Their success is backed by recent research from leading universities and represents a fundamental rethinking of how robotic dairy systems can operate.

What fascinates me most is that this isn’t just about cutting feed costs. It’s about what happens when farmers question inherited practices and discover that some of our industry’s most accepted truths might actually be holding us back.

The Discovery That Started It All

Matt Strickland, who operates Double Creek Dairy near Merced, California, didn’t set out to revolutionize robotic milking. With 500 cows and eight DeLaval VMS V300 robots, he was simply observing his herd with fresh eyes—something we could all probably benefit from doing more often.

Working alongside herd adviser Kelli Hutchings—whose Wyoming ranching background brought a completely different perspective to dairy operations—Strickland noticed something that challenged everything the industry had told him. The cows weren’t particularly excited about the robot feed. What they really wanted was to reach the feedbunk on the other side. The robot wasn’t the destination; it was more like a toll booth on the highway to fresh TMR.

“I didn’t invest in robots to feed my cows,” Strickland explains. “I got the robots to milk my cows.”

Now, that might sound obvious, but think about how much infrastructure and cost we’ve built around the opposite assumption. Over approximately two years, Strickland’s operation gradually reduced and eventually eliminated pellets from all eight robots. The results? Well, they defied everything we thought we knew:

- No significant change in robot visits

- No increase in incomplete milkings

- Milk production actually increased

- Butterfat improved by 0.3–0.4%

Today, only seven cows in Strickland’s 500-head operation still receive pellets—individual animals with specific needs that justify the cost. That’s a pretty remarkable shift from where they started.

What the Research Actually Shows

Here’s where it gets really interesting from a scientific perspective. Strickland’s experience isn’t some outlier or lucky break. Recent research from multiple institutions validates what these pioneering farmers are discovering in practice.

The University of Saskatchewan team, led by PhD student Sophia Cattleya Dondé working under Dr. Greg Penner at their Rayner Dairy Research and Teaching Facility, revealed something that should make us all pause. Changing pellet starch concentration—whether 24% or 34%—had essentially zero effect on milk production or voluntary visits. Even more eye-opening: when cows consumed additional pellets, they weren’t adding to their total intake. For every 1 kg increase in pellet intake, cows reduced their partial mixed ration intake by 0.63 kg on average. They were just swapping one feed source for another.

University of Wisconsin Extension research found something equally surprising—farms offering higher grain amounts in the robot actually produced less milk. Separate research from the University of Guelph examining Canadian farms found that feed push-up frequency correlated with higher production, with each additional five push-ups per day increasing milk yield by 0.77 lbs per cow.

It’s worth noting that the Wisconsin study also found free-traffic barns produced more milk than guided-flow barns overall, though higher pellet feeding wasn’t necessarily associated with more milk—potentially because farms feeding high pellet amounts in free-traffic systems were often compensating for poorer forage quality.

And then there’s the Vita Plus survey of 32 Upper Midwest herds from 2018 that really caught my attention. The biggest surprise? Pellet cost and composition had no effect on income over feed cost. In fact—and this is where it gets counterintuitive—farms feeding simple, low-cost pellets like corn gluten feed or basic shelled corn were more profitable than those using premium formulations.

An Important Note on Adoption

It’s worth emphasizing that pellet-free robotic milking is still an emerging practice, not yet an industry standard. While 75+ farms across Wisconsin and Ontario have successfully made this transition, and the research supports the concept, this represents early adoption rather than widespread acceptance. The equipment manufacturers continue to include pellet systems as standard, most nutritionists still recommend pellets, and the vast majority of robotic operations worldwide continue using them. What we’re seeing is growing evidence that pellets may be optional for well-managed guided-flow operations, but each farm needs to carefully evaluate whether this approach fits their specific situation. This isn’t a universal recommendation—it’s an opportunity for certain operations to consider.

Understanding the Economics: Where the Money Really Goes

Let’s talk dollars and cents, because that’s what keeps us all in business. The financial case for pellet-free operations extends far beyond just the obvious feed savings.

When you really dig into what a typical 200-cow robotic operation spends on pellet infrastructure, the numbers are eye-opening:

Annual Pellet System Costs:

- Raw pellet costs (10 lbs/cow/day at $250/ton): $91,250

- Inventory management labor: $2,500–$4,000

- Feed table programming and updates: $1,500–$2,500

- Feed waste and shrink (3–5%): $3,600–$5,400

- Rodent control (attracted by stray pellets): $1,200–$2,000

- System maintenance and calibration: $1,500–$2,500

- TOTAL ACTUAL COST: $101,000–$109,000

Now, when farms eliminate pellets, they’re not simply pocketing all these savings—that would be too easy, right? Successful transitions require reinvestment:

Required Reinvestments:

- Higher-quality forage: $800–$1,200 annually

- Increased feed push-up labor (1–2 additional hours daily): $8,760

- Enhanced monitoring systems: $2,000–$5,000

- Potential infrastructure adjustments (gate modifications if needed): $0–$15,000

NET ECONOMIC BENEFIT: $18,000–$39,000 annually, plus an additional $10,400 from butterfat improvements of 0.2–0.4%. That’s real money we’re talking about.

Regional Success Patterns: Where It’s Taking Hold

What I’ve found particularly interesting is how adoption patterns vary by region. We’re seeing the strongest uptake in Wisconsin’s central dairy corridor—about 45 farms as of late 2024—Southern Ontario around the Woodstock area with roughly 30 operations, and isolated pockets in Quebec.

Jay Heeg’s operation near Colby, Wisconsin, provides a compelling example of regional success. Heeg Brothers Dairy currently milks 1,050 cows in their conventional parlor and 450 in a new robot barn that opened in December 2023. From day one—and this is the key part—that robot barn has operated completely pellet-free using a guided-flow design.

The performance comparison really tells the story. Their robot barn with no pellets produces 98 lbs per cow per day, versus about 94 lbs in the parlor. Butterfat runs 4.5% in the robot barn. Somatic cell count? Lower in the robot barn, too.

“The cows have been performing well,” Heeg reports. “Once they’re trained, they do better without you out there in the pen.”

You know what’s notable? In these regions where multiple farms have adopted pellet-free systems, it’s becoming normalized. Once three or four neighbors prove it works, the regional skepticism evaporates pretty quickly. California remains more isolated—Strickland is still somewhat of a lone pioneer there—but Wisconsin and Ontario are seeing cluster effects.

The Reality Check: Not Every Farm Should Try This

Let me be really clear about something that doesn’t always get discussed openly. I recently spoke with a 120-cow operation in Vermont that wisely decided against attempting pellet-free after honestly assessing their situation. They had a free-flow barn, variable forage quality, and limited capital reserves. Smart decision to wait.

Not every operation is positioned to succeed with pellet-free systems. Through analyzing successful transitions and, honestly, some notable failures, four non-negotiable factors emerge.

First, you absolutely need guided traffic flow. Free-flow barns, where cows have unrestricted access to all areas, typically require pellets to maintain voluntary visits. Research from Michigan State and Cornell consistently backs this up. Guided-flow systems with pre-selection gates naturally direct cow traffic through the robot, making pellets less critical for motivation.

Second, when pellets disappear, your TMR becomes everything. And I mean everything. Successful operations maintain forage with greater than 65% NDF digestibility (test this, don’t guess), consistent moisture content with no more than 2% variation, excellent fermentation quality with pH below 3.8 and minimal heating, and fresh feed delivery timed to stimulate activity—usually 2–3 AM and 2–3 PM works best.

Third, fresh cows and heifers require dedicated training. We’re talking about bringing them through the robot manually 3 times daily for a minimum of 3–6 days. That’s approximately 18 hours of labor per fresh cow during the initial training period. It’s a front-loaded investment that pays dividends later.

And fourth, the transition requires 16–24 months of focused attention. You’ll see temporary production dips, increased fetch labor, and need systematic problem-solving skills. Farms attempting quick transitions or lacking dedicated oversight consistently fail. I’ve seen it happen multiple times—the farm that thinks they can “ease into it” over a month usually gives up by week six.

Navigating the Transition: What Really Happens

The transition to pellet-free isn’t a simple switch—it’s a carefully managed process that requires patience and, frankly, some courage during the tough weeks.

In weeks 1–2, you’ll see an immediate 10–15% production drop as cows adjust. This is normal, not a sign of failure. Keep reminding yourself of that at 4 AM when you’re questioning everything.

Weeks 3–8 are what I call the valley of despair. Fetch labor intensifies. Production remains 8–12% below baseline. You’ll have mornings when 30 cows refuse the robot, and you’re wondering what you’ve done.

But then weeks 9–16 arrive. Gradual recovery begins. Rumen function stabilizes—you can actually see this in the manure consistency. Behavioral adaptation completes, and milk components start improving.

By months 4–6, production returns to baseline or slightly higher, with improved components. The economic benefits become visible. You can actually breathe again.

Here’s the critical insight from those who’ve been through it: Most farms that fail give up during weeks 6–8 when the challenges feel overwhelming, but the benefits haven’t materialized. Understanding this as a normal phase—not a crisis—is essential for success.

Risk Mitigation: Your Exit Strategies

Something the research doesn’t always cover, but farmers need to know—what if you need to reverse course?

If production drops by more than 20% by week 8, you can reintroduce pellets at 50% of the original amount, stabilize for 2 weeks, then reassess. Several farms have successfully used this “pause and reset” approach.

Another option is to keep your fresh cows and first-lactation heifers on pellets while transitioning only mature cows. This reduces risk while you learn what works for your specific situation.

Some northern operations have found success going pellet-free during the grazing season, when TMR quality is highest, then reintroducing minimal pellets during the winter months, when forage quality varies more.

Industry Response: Reading Between the Lines

The equipment and feed industries are navigating this trend carefully, and their responses tell us a lot about where it might go.

DeLaval has published technical documents on no-feed practices and featured pellet-free farms at World Dairy Expo 2025. But here’s what’s telling—they continue to include pellet delivery systems as standard on new installations, positioning no-feed as a “specialist application” for sophisticated operators. That’s strategic positioning, not wholehearted endorsement.

Feed companies are quietly diversifying. I’ve noticed more pushing of liquid feed supplements and “alternative robot feeds” in the past year. Smart nutritionists are repositioning as “whole-system optimization” experts rather than pellet specialists. They see the writing on the wall.

Current adoption patterns and market response suggest pellet-free systems may remain in the 5–15% range for specialized operations in the near term, though exact industry projections remain speculative. The measured response from manufacturers and feed companies indicates they’re hedging their bets rather than embracing wholesale change.

Self-Assessment: Is Your Operation Ready?

| Success Factor | Must Have (Red Flag if Missing) | Warning Signs (Proceed with Caution) | Deal Breaker (Wait Until Fixed) | Your Score (✓) |

| Traffic Flow System | Guided-flow with pre-selection gates | Free-flow barn design | Free-flow without modification options | |

| Forage Quality (NDF Digestibility) | >65% NDF digestibility | 60-65% NDF digestibility | <60% NDF digestibility | |

| TMR Moisture Consistency | <2% variation | 2-3% variation | >3% variation | |

| Fresh Cow Training Capacity | 3 manual passes daily for 3-6 days | Limited labor (2 passes daily) | Cannot commit to training | |

| Financial Reserves | $50K-$70K buffer (200 cows) | $30K-$50K buffer | <$30K reserves | |

| Herd Size | >200 cows OR strong finances | 120-200 cows with tight margins | <120 cows with debt | |

| Management Time Available | 3-4 hours daily during transition | 2-3 hours daily available | <2 hours daily available | |

| Nutritionist Support | Aligned and supportive | Neutral or uncertain | Actively opposed |

Before you even think about attempting a pellet-free transition, honestly evaluate your readiness. And I mean honestly—not optimistically.

For your facility, do you have guided-flow traffic with properly sized commitment pens at 6–7 cows per robot? Can cows move from the robot to the feedbunk without bottlenecks? Are your gates reliable and well-maintained?

Looking at your forage program, can you maintain consistent TMR quality with no more than 2% dry matter variation? Do you have covered storage and quality testing protocols? Is your forage digestibility consistently above 65% NDF?

And for management capacity—this is crucial—can you dedicate 3–4 hours a day to training during the transition? Do you have financial reserves to absorb $50,000–$70,000 in transition losses for a 200-cow herd? Are your nutritionist and veterinarian aligned and supportive?

Score yourself honestly on each dimension. Operations with strong capabilities across all areas are excellent candidates. Those with multiple weaknesses should address fundamental issues before attempting this transition.

Looking Beyond Pellets: What This Really Means

This pellet-free movement reveals something bigger than operational optimization. It demonstrates how entire industries can build complex systems around assumptions that never get questioned.

Think about it—this pattern of inherited practices becoming unquestioned truth likely exists in other areas of dairy management we haven’t even examined yet. Three-times-daily feeding schedules—is it really necessary? Complex genetic selection protocols—how much complexity actually adds value? Traditional parlor labor models—could workflow redesign cut labor 30%? Precision feeding systems—does the complexity justify the cost?

The farms that will thrive in the coming decades won’t be those perfecting existing systems. They’ll be those willing to ask uncomfortable questions about fundamental assumptions.

Key Takeaways for Your Operation

For operations considering pellet-free transitions, here’s what matters most.

First, assess your readiness honestly. This works brilliantly for farms with guided-flow barns, strong forage programs, and management capacity to weather transition challenges. It fails predictably for operations lacking these foundations.

Second, budget for the transition period. Expect 8–12 weeks of production losses totaling $50,000–$70,000 for a 200-cow operation. If you can’t absorb this without financial stress, wait until you can.

Third, connect with others who’ve done it. Reach out to producers in Wisconsin’s central corridor or Southern Ontario who’ve successfully transitioned. Their practical insights are invaluable. The Dairy Farmers of Wisconsin maintains a peer network list, and several Ontario producer groups facilitate farm visits.

Fourth, consider your regional context. If other farms in your area have successfully transitioned, you’ll face less skepticism from advisers and find more peer support. Being the regional pioneer is significantly harder.

And fifth, think generationally. Young farmers building new operations should seriously consider guided-flow, pellet-free designs from the start. It’s much easier than retrofitting later.

For specific guidance and support, the University of Wisconsin-Madison Extension offers robotic milking workshops quarterly. Contact Dr. Francisco Peñagaricano and his team. The University of Saskatchewan provides research updates through its Rayner Dairy facility, led by Dr. Greg Penner’s team. Cornell PRO-DAIRY maintains an AMS discussion group for Northeast producers. And the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture hosts pellet-free transition webinars through their Dairy Team.

What’s encouraging is that the pellet-free revolution isn’t really about pellets. It’s about recognizing that dairy innovation comes from farmers willing to test assumptions, not from equipment manufacturers or feed companies protecting existing business models.

As one Wisconsin dairy extension specialist told me recently: “The most valuable skill for the next generation of dairy farmers isn’t optimizing current systems—it’s questioning whether those systems are actually optimal.”

That questioning mindset, more than any specific practice or technology, will determine which operations thrive in an evolving dairy landscape where labor is scarce, margins are tight, and consumer preferences keep shifting.

The farms making these transitions today aren’t just saving money on pellets. They’re developing the adaptive capacity that will serve them regardless of what challenge comes next. And in an industry facing constant change, that capability might be worth more than any amount of feed savings.

Sometimes seeing it work on a neighbor’s farm is worth more than all the research papers combined. And that’s exactly what’s starting to happen across Wisconsin and Ontario—one successful transition at a time.

Have you tried reducing the number of pellets in your robot herd? What’s been your experience—success, challenges, or somewhere in between? Tell us in the comments below.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Feed Smart: Cutting Costs Without Compromising Cows in 2025 – Reveals actionable strategies to lock in over $200 per cow in savings through alternative protein sourcing and precision feeding technology, providing a tactical roadmap that directly complements the cost-reduction goals of the pellet-free system.

- Decide or Decline: 2025 and the Future of Mid-Size Dairies – Analyzes why mid-size herds must pivot from traditional expansion to intense optimization—like the pellet-free model—to survive, offering a crucial strategic roadmap for financial resilience and decision-making in the challenging 2025 dairy market.

- Robotic Milking Revolution: Why Modern Dairy Farms Are Choosing Automation in 2025 – Delivers a comprehensive ROI breakdown and labor-saving analysis for modern automated systems, validating the operational efficiency gains and data capabilities that make advanced robotic management essential for future-proofing your dairy business.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!