Rachel Craun and Jon Chapman didn’t inherit easy paths. They’re carving new ones—and in doing so, they’re teaching us what loyalty to an industry really looks like.

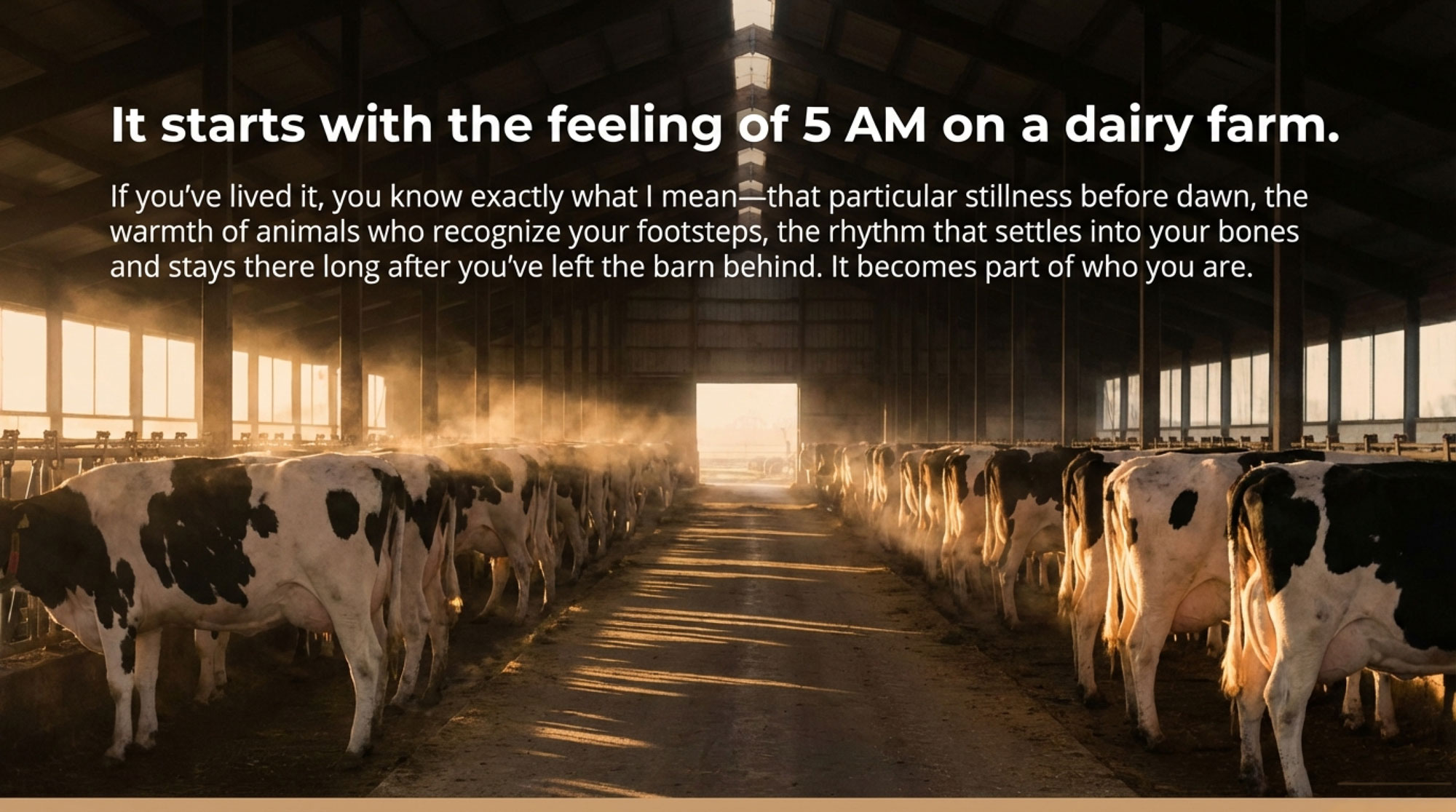

There’s something about 5 AM on a dairy farm that never leaves you.

If you’ve lived it, you know exactly what I mean—that particular stillness before dawn, the warmth of animals who recognize your footsteps, the rhythm that settles into your bones and stays there long after you’ve left the barn behind. It becomes part of who you are in ways you can’t quite explain to anyone who hasn’t experienced it.

Rachel Craun knows that rhythm intimately. She’s been living it since childhood on her family’s dairy operation in Mount Crawford, Virginia. Now she’s at Purdue University, active in the Dairy Club and finding real success on the Collegiate Dairy Judging team.

The Virginia mornings are behind her, at least geographically.

But over a dozen years of dairy farming rhythms? Those don’t care about geography. They travel with you wherever you go.

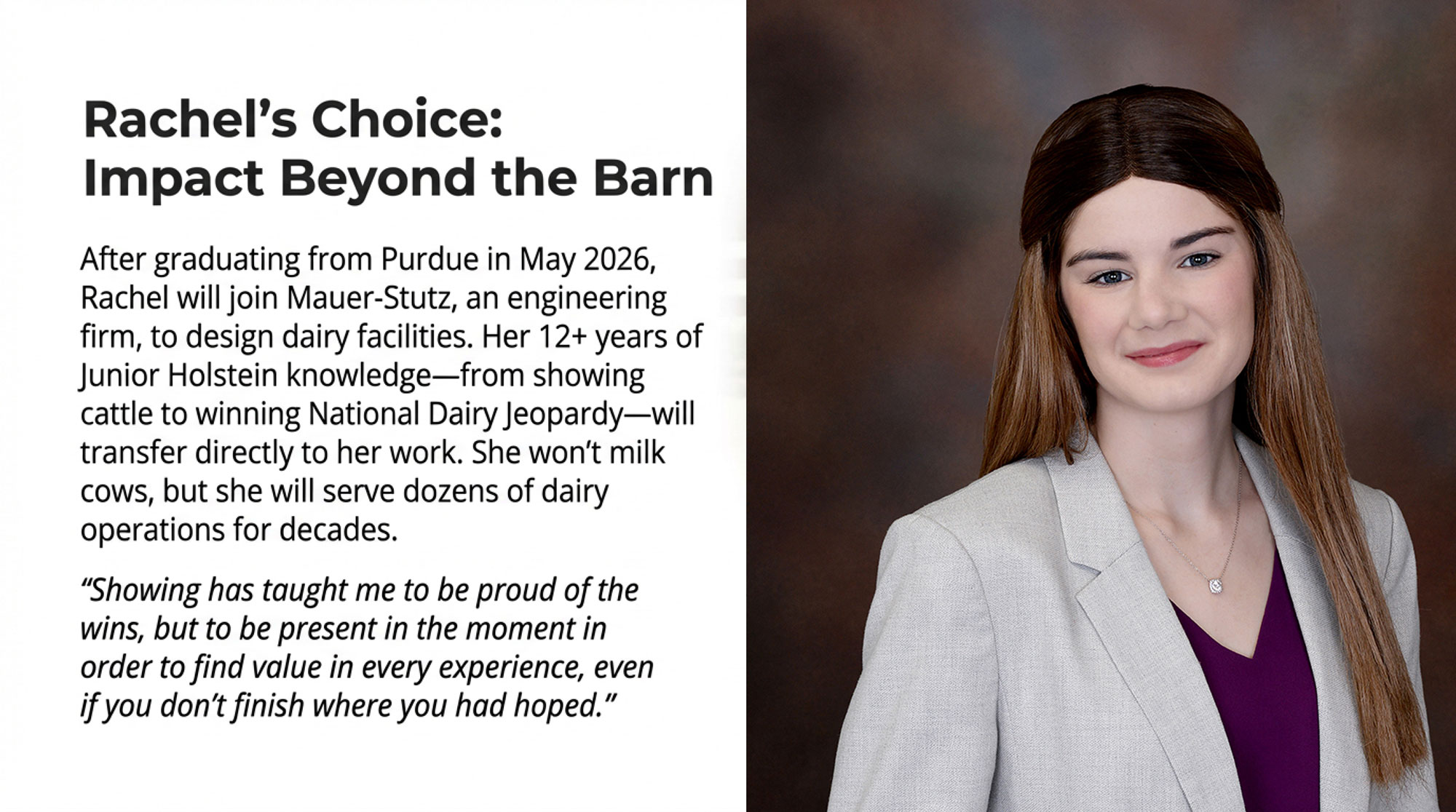

“Showing has taught me to be proud of the wins,” Rachel says, “but to be present in the moment in order to find value in every experience, even if you don’t finish where you had hoped.”

I’ve read that quote several times now, and what moves me most isn’t the words themselves—it’s how much living must be packed into them. Over a dozen years of Junior Holstein involvement. More than a decade of early mornings, weekend shows, long drives home after placings that didn’t go the way she’d hoped. The kind of quiet, persistent commitment that shapes who you become when nobody’s watching.

Three thousand miles away in Keyes, California, Jon Chapman carries a similar weight in his heart. His family operates a Holstein dairy in the Central Valley, and Jon has been part of it since he could walk.

Ten years. Let that sink in for a moment. Ten years serving on the officer team for the California Junior Holstein Association. He’s currently serving as chairman of the Junior Advisory Committee, representing dairy youth across the entire West Coast. He’s competed at the International Junior Holstein Show at World Dairy Expo twice—because once, apparently, wasn’t enough to satisfy his love for this industry.

“Regardless of placings,” Jon says, “I am proud of my efforts, in my sportsmanship, and the dedication that goes into raising Holsteins year-round—not just walking in the showring.”

There it is again. That word: dedication. Not to winning. Not to trophies. To showing up.

This past year, Rachel and Jon received the Judi Collinsworth Memorial Scholarship—Rachel receiving the top $1,000 scholarship, Jon receiving the $500 scholarship. The amounts seem modest against the backdrop of modern education costs.

But what moved me most about researching their stories wasn’t the scholarship itself.

It was understanding what these two remarkable young people represent—and the uncomfortable questions their choices force us to ask about what it actually means to invest in dairy’s future.

The Woman Who Saw What Others Missed

Judi Collinsworth dedicated her career to Holstein Association USA in Brattleboro, Vermont. As Executive Director of Member and Industry Relations, she was responsible for telemarketing, member programs, and—this is the part that matters most—spending a great deal of her time improving and expanding the programs available to Holstein youth.

She passed away in late 2023.

What she left behind can’t be measured in program budgets or press releases. It’s something far more precious than that.

She built something harder to name. Call it permission. Call it space. Call it the radical, beautiful idea that you could love dairy with your whole heart and still have a life beyond the barn.

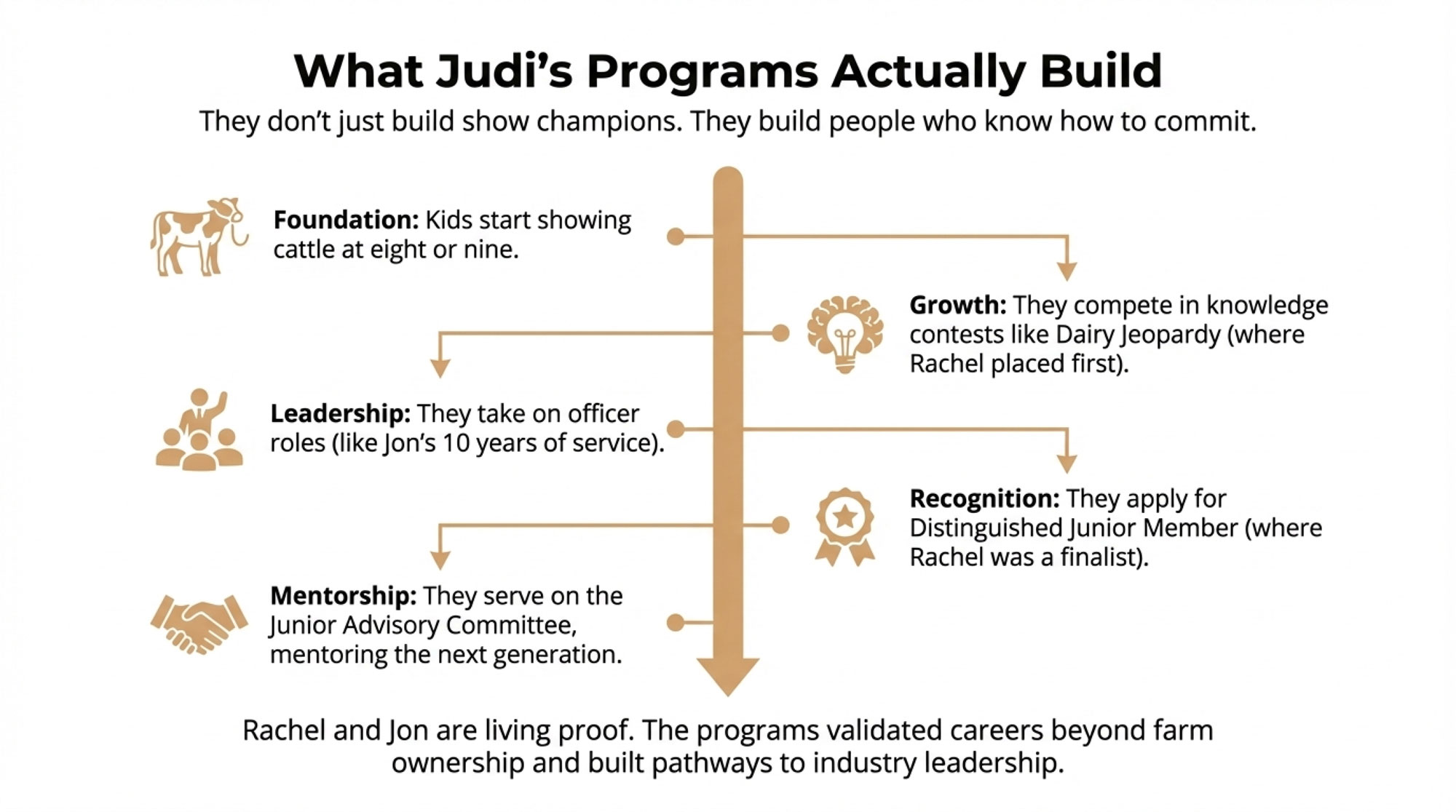

Think about what that means for a young person growing up on a farm. The programs Judi championed fostered an identity formation that unfolds over the years, layer by layer. Kids start showing cattle at eight or nine—nervous, uncertain, not yet knowing what they’re becoming part of. By their early teens, they’re taking on officer roles, competing in knowledge contests, and learning to win and lose with grace. By high school, they’re applying for Distinguished Junior Member, standing before judges who’ve read their entire dairy journey in a book they wrote themselves.

By their early twenties? They’re serving on the Junior Advisory Committee, mentoring the nervous kids who remind them of themselves at eight.

Rachel Craun walked every step of that path. And here’s where her story takes my breath away.

She placed first in the National Dairy Jeopardy contest. First. In a competition that requires you to care enough about this industry to fill your head with knowledge most people will never need. She placed first in the National Virtual Interview, too.

Then came Distinguished Junior Member. Rachel was named a finalist—one of only six young people in the entire country selected for that honor. Six. Out of everyone who applied, everyone who dreamed, everyone who worked for years toward that recognition.

She served in officer roles on the Virginia Holstein Association. She competed at the International Junior Holstein Show at World Dairy Expo in 2025—a goal she’d set for herself years ago and then actually achieved.

Jon Chapman walked the same path, just from the other side of the country. A full decade of officer service. Two-time International Junior Holstein Show competitor. Currently, the chairman of the Junior Advisory Committee.

These aren’t résumé lines. They’re evidence of something rare and beautiful: young people who kept showing up when nobody was watching. When it would have been easier to quit. When the world offered a thousand other things to care about.

Judi Collinsworth would have recognized them immediately.

Not because they won everything.

Because they never stopped coming back.

The Math Nobody Wants to Talk About

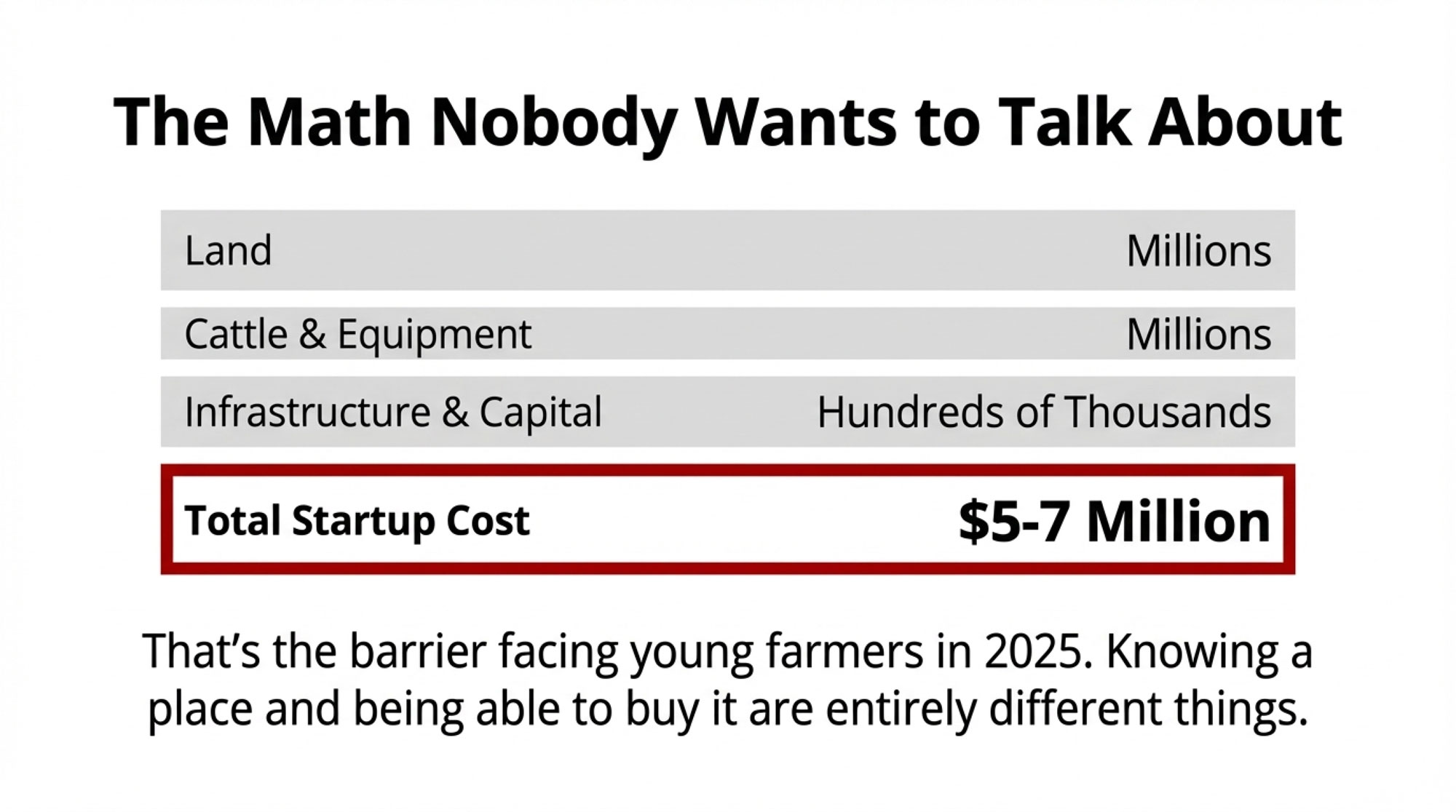

I need to be honest about something, because this is where the story gets complicated—and painful. It’s the part that keeps me up at night when I think about the future of this industry.

Rachel knows her family’s farm the way you only know a place you’ve grown up in. The sounds. The rhythms. The particular way a barn feels in early morning when the animals are stirring and the day hasn’t quite started yet. That bone-deep connection that becomes part of your soul.

But knowing a place and being able to buy it are entirely different things.

Let’s look at what it actually takes to acquire a dairy operation in 2025. Land alone, at current prices in productive dairy regions: millions of dollars. Add cattle, and you’re deeper in. Machinery. Buildings. Infrastructure. Operating capital for the first year, when everything feels uncertain.

By the time you’ve accounted for everything required actually run a dairy, you’re looking at capital requirements that can easily exceed $5-7 million for a viable operation. We’ve been tracking these numbers throughout 2025—in pieces like “What Lactalis’s 270-Farm Cut Really Means for Every Producer” and “The Four Numbers Every Dairy Producer Needs to Calculate This Week“—and they keep moving in the same direction.

After graduating in May 2026, Rachel plans to work full time for the agricultural division of Mauer-Stutz, an engineering firm based in Peoria, Illinois.

I don’t have to tell you what that math means.

You already know.

Jon faces the same impossible arithmetic in California, where land prices run even higher. His family’s operation represents capital accumulation across generations—the kind of investment that no 22-year-old can replicate, no matter how deep their commitment. No matter how many trophies they’ve earned. No matter how much they love this with everything they have.

So Jon is studying Agriculture Systems Technology at Iowa State University. He hopes to help dairymen realize greater efficiency and profitability through innovative facility designs and concepts.

Both of them love Holsteins.

Both of them are staying in the dairy industry.

Neither of them is becoming a dairy farmer.

Sit with that for a moment. Because I think it tells us something important—and heartbreaking—about where we are.

What a Decade of Saturdays Actually Looks Like

I want to stay with Jon’s story for a moment, because I think it illuminates something important about the quiet heroism of showing up.

Ten years serving on the officer team.

What does that actually mean? It means Saturday mornings when he could have slept in like his friends. Meetings in towns he’d never otherwise visit. Phone calls to coordinate volunteer coverage for the next show. Budget reviews that nobody will ever thank you for. The thousand small decisions that keep youth organizations functioning—decisions that matter enormously and earn almost no recognition.

California’s Central Valley isn’t far from the coast. While Jon was organizing junior Holstein events, plenty of his peers were spending summer weekends at the beach. Nobody would have blamed him for making a different choice.

But something kept him coming back. Year after year. Meeting after meeting. Something in his heart that wouldn’t let go.

“Regardless of placings, I am proud of my efforts, in my sportsmanship, and the dedication that goes into raising Holsteins year-round—not just walking in the showring.” — Jon Chapman, JAC Chairman

The return on a decade of service isn’t trophies. It’s something harder to measure, but infinitely more valuable.

It’s the nervous first-time exhibitor who discovers she can actually speak in front of a crowd. It’s the kid who almost quit but didn’t, because someone made him feel like he belonged. It’s the programs and pathways that help the next generation find their place—pathways Jon helped build with ten years of Saturdays.

Two Paths to Staying in Dairy

| Traditional Path | New Professional Path | |

| Entry Point | Inherit family operation | Youth programs, education, and industry service |

| Capital Required | $5-7 million+ | Education investment |

| Daily Work | Milking, feeding, and managing the herd | Designing facilities, consulting, systems optimization |

| Industry Impact | One operation | Dozens of operations over a career |

| Example | Previous generations | Rachel Craun (Mauer-Stutz engineering) and Jon Chapman (Agriculture Systems Technology) |

That’s what service multiplies.

That’s what showing up creates.

We wrote about this same truth earlier this year in “This Was Never About the Cattle: What the TD 4-H Classic Really Teaches at 5:47 AM.” The pattern holds: what youth programs actually build isn’t show champions. It’s people who know how to commit.

What a Generation Had (And What Changed)

To understand what’s different now, you need to understand what dairy farming used to offer—and what’s been lost.

There was a time—within living memory, within your grandparents’ memory—when inheriting a farm meant inheriting a community. When the neighbor who helped you fix the fence in April was the same neighbor whose hay you helped bring in come August. When everyone in a ten-mile radius knew whose cows were whose, and that knowledge itself was a kind of wealth you couldn’t put a price on.

That world made different choices possible.

A young farmer starting out didn’t need to finance everything alone, because they weren’t alone. They stepped into a web of relationships that had been forming since before they were born. When disaster struck—a barn fire, a failed crop, a death in the family—the community showed up. Not out of charity, but out of reciprocity. You helped because someday you’d need help too.

That mutual obligation functioned as a kind of informal insurance. It reduced capital needs. It created resilience that individual families couldn’t achieve alone.

That world is largely gone now.

Thousands of dairy farms have closed in recent years. The remaining operations grow larger, more capital-intensive, and more dependent on professional management and specialized expertise. The web of relationships that held earlier generations has thinned and frayed.

I understand why Rachel and Jon made different choices.

The infrastructure that held their grandparents’ generation simply isn’t there to hold them.

What Judi Actually Built

So what did Judi Collinsworth create, knowing the world was changing faster than anyone wanted to admit?

She made space.

Space for young people like Rachel and Jon to love dairy and still have lives. To serve the industry without being crushed by the economics that make farm ownership impossible for most. To be dairy people in whatever form that identity could survive.

The programs Judi championed didn’t promise anyone a farm. They promised something more durable: a sense of belonging that could survive career pivots, geographic moves, and economic impossibility. A home in this industry that wasn’t dependent on owning land.

Rachel can work in Peoria, designing facilities for dairy operations, and still be a dairy person. Her knowledge doesn’t disappear because she’s not milking cows. It transfers—to facility designs that actually work for farm families, because she understands how farm families actually live.

Jon can consult for California dairies and still bring 10 years of officer service to every client conversation. He knows what matters to producers because he grew up as one.

The scholarship named in Judi’s honor does exactly what she designed her programs to do. It recognizes sustained commitment. It validates alternative pathways. It signals that the industry values expertise even when that expertise doesn’t come with a barn attached.

The Investment Nobody Calculates

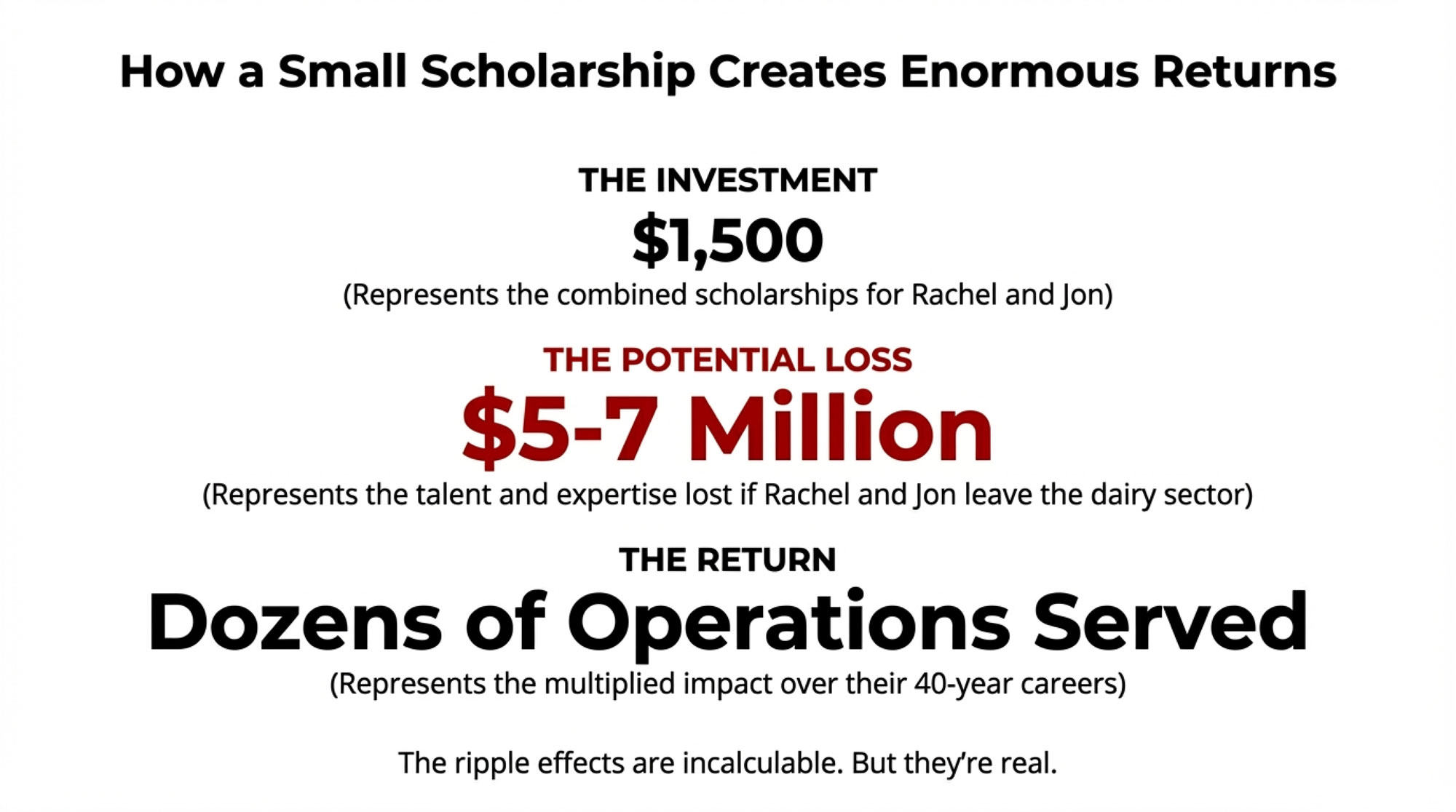

What does $1,500 in scholarships actually buy?

Not farm owners. Not solutions to the capital barrier. Not a reversal of the consolidation reshaping the industry.

But consider what that modest investment actually creates.

Rachel, without validation from her industry, might have taken her engineering skills somewhere else entirely. Designing facilities for companies that process soybeans, corn, anything but dairy. Her deep knowledge—earned through twelve years of showing cattle, competing, serving—flowing to sectors that had nothing to do with the cows she grew up loving.

Jon, without recognition for his decade of service, might have applied his systems expertise to Silicon Valley startups. Agricultural technology serving every sector, dairy is just one line item among many.

Instead, they’re staying.

Not as farmers. But as professionals who will serve dozens of operations over their careers. Engineers and consultants who bring genuine dairy knowledge to their work because they lived it before they studied it.

Rachel will spend her career designing agricultural facilities. Each one will work better because she knows what the rhythm of a dairy operation feels like from the inside.

Jon will help California dairies implement technologies that actually fit their operations—because he understands producer decision-making from a decade of serving producers.

The ripple effects are incalculable.

But they’re real.

What Stays With You

Ask what over a dozen years of showing cattle, competing in knowledge contests, and serving in leadership roles actually taught Rachel and Jon, and certain truths emerge:

Sustained commitment matters more than occasional brilliance. Anyone can show up once. Showing up for a decade—through middle school awkwardness, high school social pressure, college course loads—proves something about who you are.

Resilience isn’t about winning. It’s about finding value in every experience, especially the losses. The placings you hoped for and didn’t get. The classes where nothing went right. The years that tested whether you really loved this.

Service creates ripples you’ll never fully see. Ten years of officer meetings. Programming that helped young people discover confidence they didn’t know they had. That’s how commitment multiplies—in ways the person serving may never know about.

The Bottom Line

The dairy industry stands at a crossroads it didn’t choose and can’t avoid.

Farm ownership has become economically impossible for most young people, no matter how deep their commitment. The capital requirements have outpaced anything individual families can accumulate. The support structures that once made small operations viable have changed fundamentally.

We can rage against this reality.

Or we can adapt to it.

Rachel Craun and Jon Chapman represent adaptation. Not abandonment—never abandonment—but evolution. A new way of serving an industry they love, sustainable across a 40-year career, creating value for dozens of operations instead of struggling to save one.

The Judi Collinsworth Memorial Scholarship recognizes that evolution. It says to every Junior Holstein member watching: You can love this industry and still have a life. You can honor your heritage without destroying yourself. There are multiple pathways to being a dairy person.

An earlier generation had one path: inherit the farm, work the land, pass it to your children. That path created something beautiful, and its transformation deserves to be mourned.

But Rachel and Jon are creating something new. Professionals rooted in dairy knowledge, serving an industry in transition, carrying forward the values that matter even as the structures change.

Somewhere, Rachel is preparing for graduation—ready to join Mauer-Stutz and build the kind of expertise that will help dairy facilities work better for the families who use them.

And somewhere, Jon is thinking about the next generation of junior members. The nervous kids who’ll discover, as he did, that service matters more than trophies.

They’re not abandoning dairy.

They’re ensuring it has a future.

And watching them build it—two young people who found a way to love this industry without being destroyed by it—I think Judi Collinsworth would recognize exactly what she helped create.

Not the future anyone imagined.

But maybe the only one that was ever possible.

If you know a young person wrestling with how to stay in dairy when farming isn’t possible, share this with them. Sometimes knowing you’re not alone changes everything.

The National Holstein Foundation administers the Judi Collinsworth Memorial Scholarship. Learn about youth scholarship opportunities and how to support the next generation of dairy professionals at holsteinusa.com/future_dairy_leaders.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- $5-7 million says it all: That’s what a viable dairy startup costs now. Loving this industry and owning a farm are no longer the same thing—and pretending otherwise fails the next generation.

- One farm or dozens of clients? Rachel Craun will design dairy facilities. Jon Chapman will optimize dairy systems. Over 40-year careers, they’ll serve more operations than any single farm ever could.

- Youth programs build professionals, not just champions: Rachel’s 12+ years of Junior Holstein involvement and Jon’s decade as a California officer created expertise that transfers directly to careers serving this industry.

- What Judi Collinsworth actually built: Programs that let young people love dairy without being crushed by its economics. Rachel and Jon are living proof.

- If your kid loves dairy but can’t afford to farm: They haven’t failed. There’s a path forward. Share this with them.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

What happens when young people who’ve dedicated their lives to dairy can’t afford to farm? Rachel Craun and Jon Chapman just answered that question. Craun won National Dairy Jeopardy, won National Virtual Interview, became one of only six Distinguished Junior Member finalists nationally, and after graduating from Purdue in May 2026, she’ll design dairy facilities at Mauer-Stutz engineering, not milk cows. Chapman served 10 years on the California Junior Holstein officer team, now chairs the national Junior Advisory Committee, and is studying at Iowa State to help dairies he’ll never own run better. Both just received the Judi Collinsworth Memorial Scholarship, honoring the Holstein Association USA executive who built programs that let young people love dairy without being crushed by its economics. With farm startups demanding $5-7 million in capital, they represent a new path: professionals who’ll serve dozens of operations over a lifetime, rather than struggling to save one. They’re not leaving dairy—they’re the reason it will survive.

Learn More

- The Rules Changed and Nobody Told You: Three Paths Left for the 300-Cow Dairy – Arms you with the exact financial benchmarks required to choose between a $5 million scale-up or a premium market pivot, ensuring you don’t burn family equity waiting for a commodity market that no longer rewards “the middle.”

- Decide or Decline: 2025 and the Future of Mid-Size Dairies – Exposes the “cost of waiting” that quietly drains 8% of farm equity annually and breaks down why regional infrastructure now dictates your survival strategy more than your individual management ability or ancestral tradition.

- When the Labor Well Runs Dry: How Smart Dairies Are Turning Crisis into Competitive Edge – Reveals how precision automation is converting traditional labor into high-value monitoring roles, delivering a 40% higher ROI for operations that treat technology as a human multiplier rather than just a mechanical replacement.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.