$2.46 an hour. That’s what Aussie farmers earned during deregulation’s worst days. Time to talk feed efficiency?

You know what keeps me up at night sometimes? It’s this number: $2.46 an hour. That’s what some Australian dairy farmers were effectively earning during the worst stretches after their industry got deregulated back in 2000. Not their actual paycheck, mind you, but when you crunch the real numbers—milk prices, input costs, those brutal 70-hour weeks we all know too well—that’s what it amounted to for way too many operations.

As we watch trade negotiations swirl around our own supply management system up here in Canada, and as U.S. farmers deal with their own volatile markets, Australia’s quarter-century experiment offers some pretty sobering insights about what happens when you let pure market forces run the show.

I’ve been reviewing the new ABARES report on Australian dairy deregulation that was just released, and frankly, the story it tells should prompt every dairy farmer in North America to pause and think. Because what happened in Australia? It wasn’t just policy wonks moving numbers around. It was real farms, real families, real communities getting turned upside down.

When “Get Big or Get Out” Actually Happens

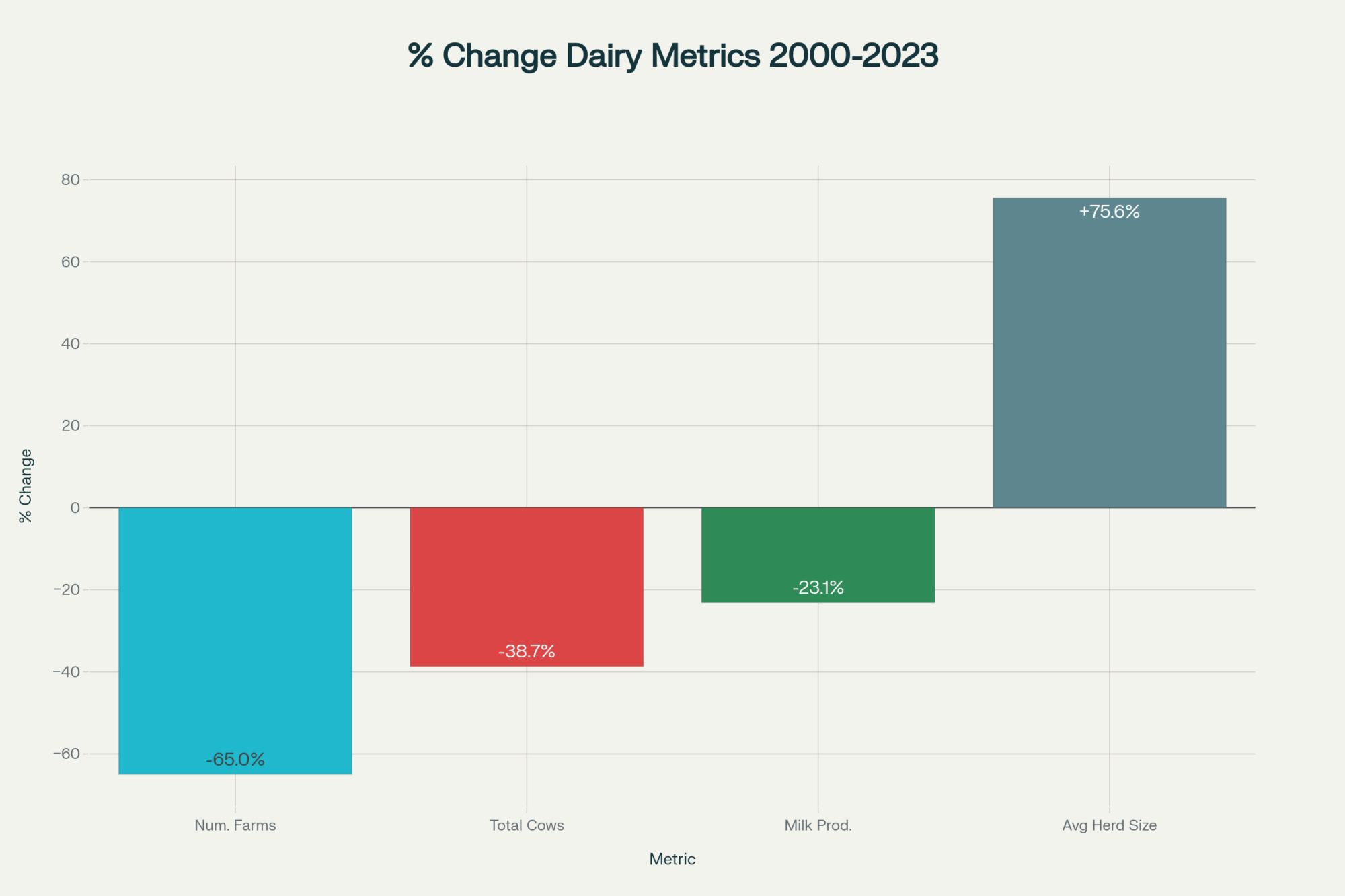

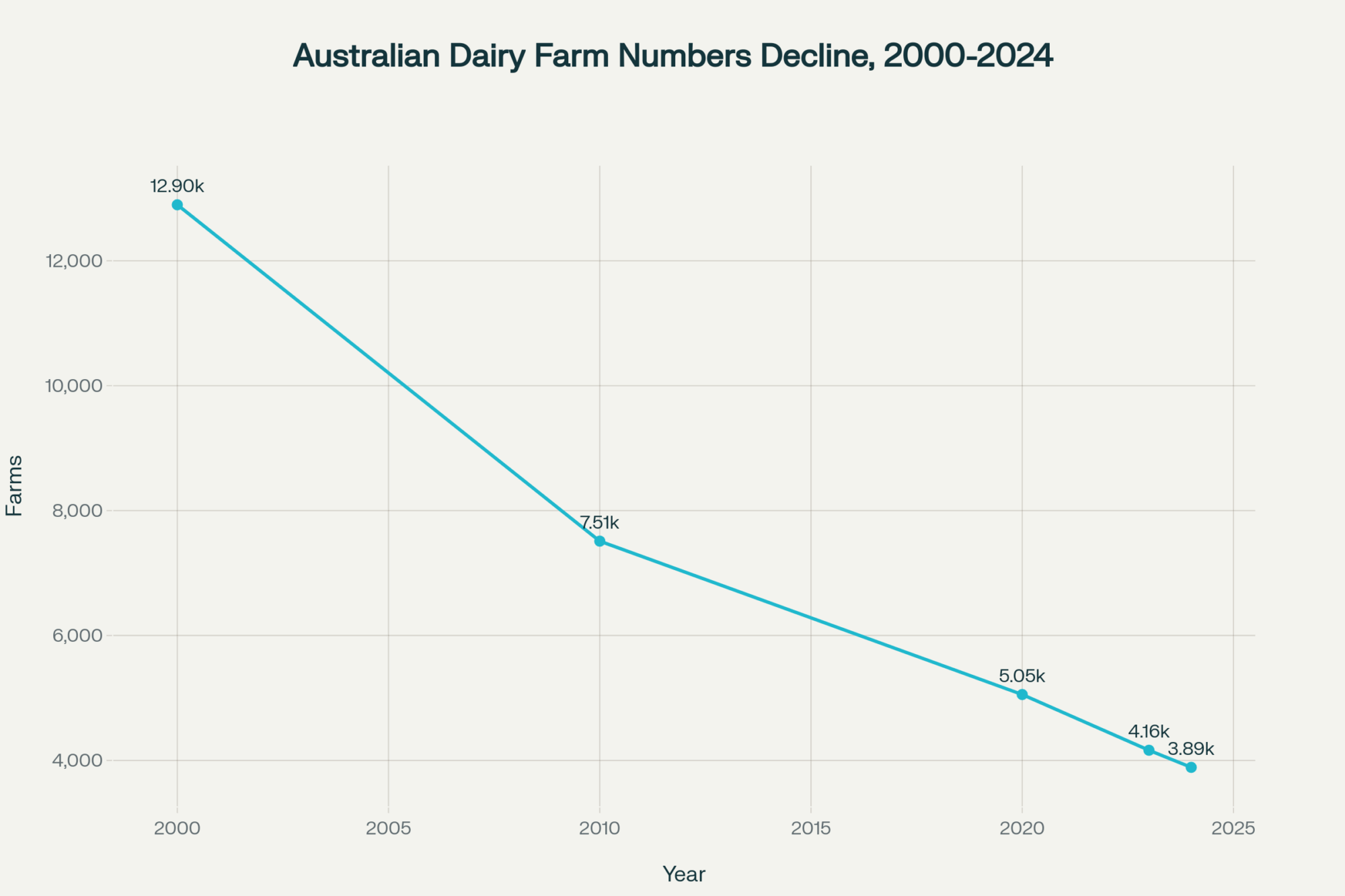

Let’s start with the raw numbers, because they’re honestly staggering. In 2000, Australia had 12,888 dairy farms. Today? They’re down to just over 4,500. That’s a 65% drop—we’re talking about more than 8,000 farm families who had to walk away from operations that, in many cases, had been in their families for generations.

Now, the efficiency crowd will tell you this is exactly what should happen. Market forces are reallocating resources to their most productive use, and all that. And, indeed, the farms that survived became dramatically more productive. Average herd sizes went from 168 cows to 534 cows. Individual farm milk production jumped by 570% between the late ’70s and today.

But despite all this consolidation and efficiency, total milk production in Australia actually fell by 26% from its peak. You have farms that are three times bigger, cows that produce more milk per head, all the latest technology and management practices, and yet the country is producing a quarter less milk than it did 25 years ago.

That’s not efficiency—that’s an industry contracting while individual operations get more intensive just to survive.

The Power Shift Nobody Talks About

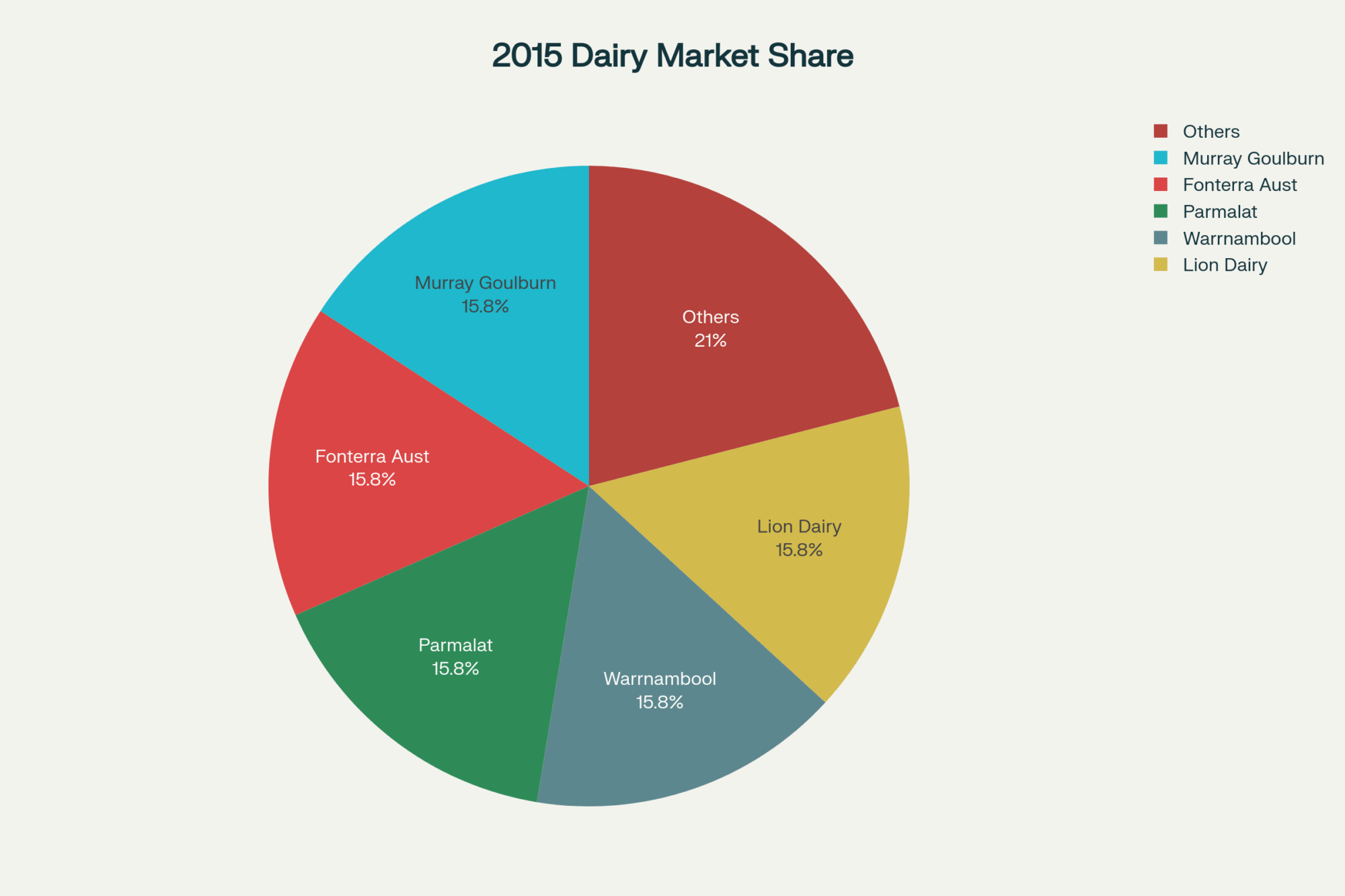

What really gets me about the Australian story isn’t just the farm consolidation—it’s what happened to the power dynamics in the supply chain. Because when you remove price supports and marketing boards, you don’t just create a “free market.” You create a vacuum that gets filled by whoever has the most leverage.

In Australia’s case, this meant that five major processors—Murray Goulburn, Fonterra Australia, Parmalat, Warrnambool Cheese & Butter, and Lion Dairy & Drinks—ultimately controlled 79% of the national milk supply by 2015. Meanwhile, two supermarket chains, Coles and Woolworths, account for approximately 65% of grocery sales.

Then came what Aussie farmers call the “$1 milk wars.” In 2011, Coles dropped the price of their private-label milk to just $1 per liter. Woolworths matched it immediately. And while the retailers claimed they were absorbing the discount themselves, we all know how that story ends, right?

As one Woolworths executive admitted to a Senate inquiry, those low prices inevitably “flow back to processors and farmers as new supply and pricing agreements are negotiated.” Which is exactly what happened. The Queensland Dairyfarmers’ Organisation documented that 185 of their members collectively lost more than $767,000 in just the first seven months of the price war.

This is what really worries me about the “let the market decide” mentality. Markets don’t operate in a vacuum. When you remove farmer protections, you don’t automatically achieve perfect competition—you often get a few large players using their leverage to squeeze out everyone else.

The Human Cost: When Communities Unravel

I’ve attended numerous dairy conferences over the years, and one thing I’ve noticed is how we often discuss “structural adjustment” as if it were just numbers on a spreadsheet. But every one of those farm exits represents a family that had to give up not just their livelihood, but usually their way of life as well.

Take Strathmerton, Victoria. Small town, about 300 people, built around a Bega cheese processing plant that had been there for decades. In 2022, Bega announced they were closing the facility to achieve “operational efficiencies.” Three hundred jobs—gone.

The local primary school enrollment dropped from 110 kids to 58 practically overnight. The town bakery that relied on the factory workers? Facing closure. One longtime resident told reporters it felt like signing “a death warrant for an entire rural community.” And honestly, when you look at what’s happened across rural Australia, that’s not hyperbole. It’s a pattern that has repeated itself in dairy communities across Queensland, New South Wales, and other regions that have lost their processing infrastructure.

The social fabric of these places gets shredded. Young people leave because there are no jobs. Services disappear because there aren’t enough people to support them. Property values collapse. And once that spiral starts, it’s incredibly hard to reverse.

The Productivity Paradox We Need to Understand

Now, I don’t want to paint this as all doom and gloom, because there are some genuinely impressive aspects of what Australian dairy farmers have accomplished. The individual farm productivity gains are remarkable. We’re talking about operations that have completely revolutionized how they manage everything from genetics to nutrition to labor efficiency.

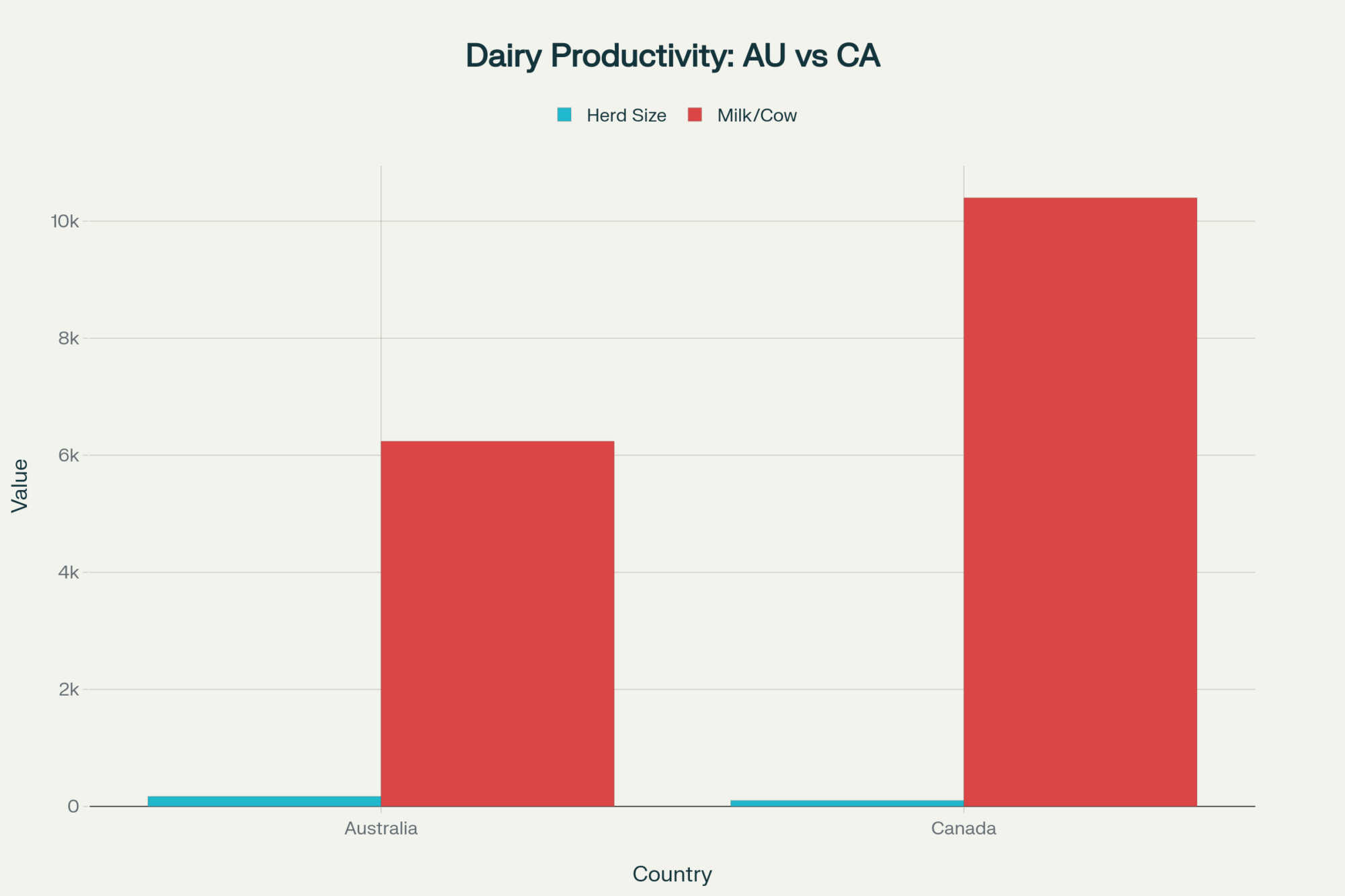

The average annual milk production per cow in Australia has increased from approximately 3,340 liters in the mid-1980s to over 6,240 liters today. They’ve embraced precision agriculture, automated milking systems, advanced herd management software—all the tools that us North American farmers are familiar with, and some we’re still catching up on.

| State/Region | Farm Loss % (2000-2022) | Key Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Queensland | -80% (1,545 → <300) | Market milk states hit hardest |

| New South Wales | -85% (1980-2021) | Lost quota value overnight |

| Victoria | -40% (4,268 → 2,552) | Export-focused, better positioned |

| Tasmania | +39% milk production | Comparative advantage regions grew |

But all this individual farm efficiency hasn’t translated into a stronger, more resilient industry overall. Production has become geographically concentrated in just a few regions—primarily the Murray-Darling Basin and Tasmania. That concentration makes the entire national supply vulnerable to regional droughts, changes in water policy, and other localized shocks.

It’s like having a smaller number of really efficient engines, but they’re all located in the same place and running on the same fuel supply. More efficient individually, but more fragile as a system.

What Canada’s Doing Right (And Why It Matters)

| Metric | Canada (Supply Management) | Australia (Deregulated) |

|---|---|---|

| Farm Numbers (2000-2023) | Stable (~10,000-11,000) | -65% (12,888 to 4,500) |

| Price Stability | Predictable, regulated prices | Volatile, market-driven |

| Farmer Age Crisis | Young farmers still entering | <6% under 35 years old |

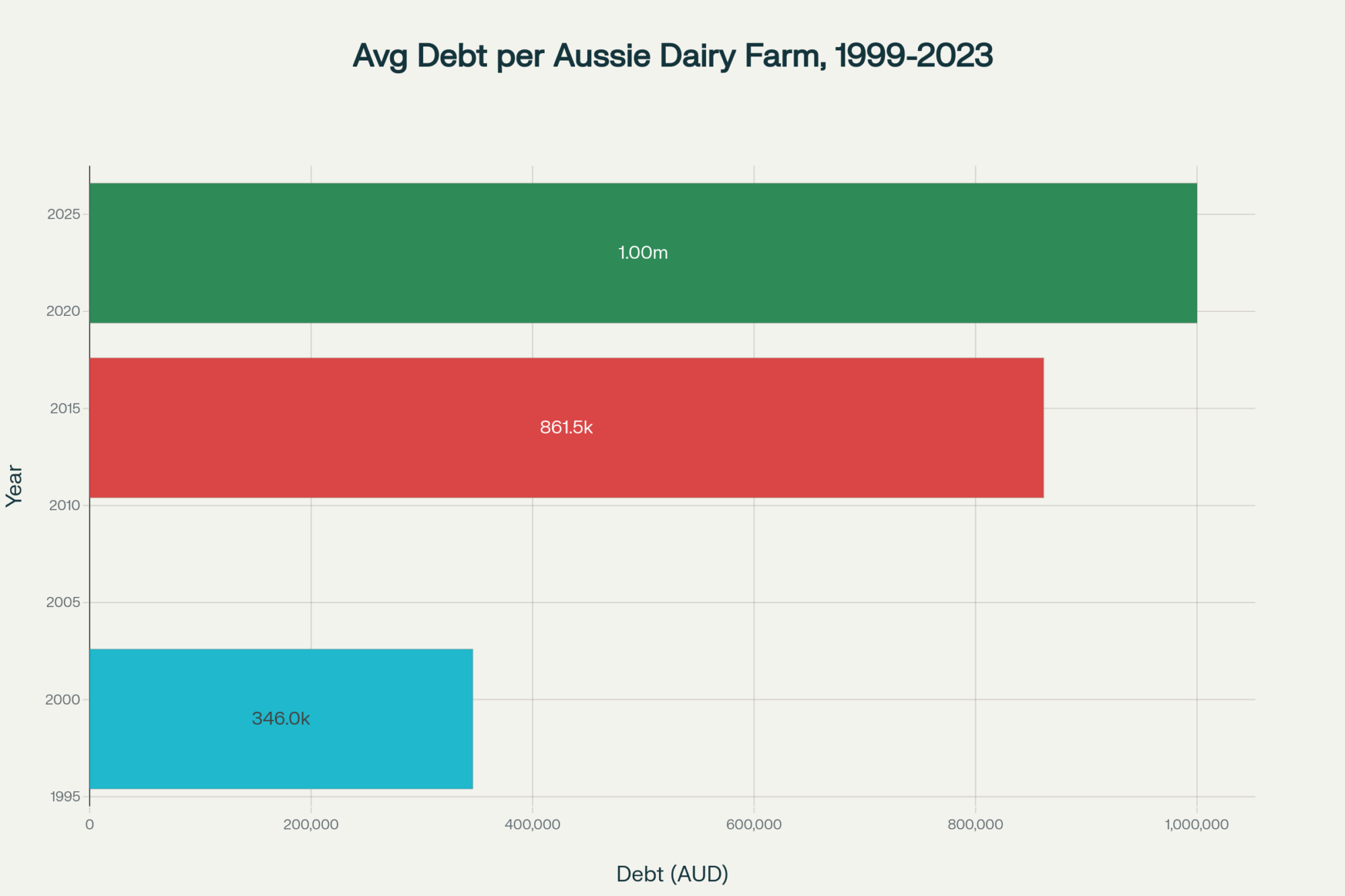

| Debt Levels | Manageable with stable income | Doubled: $346K to $861K |

| Rural Communities | Stable processing infrastructure | Widespread plant closures |

| Long-term Planning | 3-5 year investment horizons | Survival mode, short-term focus |

This is where I think we need to step back and really appreciate what we have up here in Canada. Our supply management system is often criticized—especially in trade negotiations—but when you examine what has happened in Australia, it becomes quite clear what we’re protecting.

First off, our farm numbers have been relatively stable. We’ve seen some consolidation, sure, but nothing like Australia’s 65% crash. Statistics Canada data show that we’ve maintained roughly 10,000-11,000 dairy farms nationally, with gradual, manageable changes rather than traumatic disruptions.

More importantly, our farmers can actually plan for the future. When you know what milk prices are going to be, you can make rational decisions about herd expansion, facility upgrades, and succession planning. Australian farmers, meanwhile, are dealing with the kind of price volatility that makes long-term planning almost impossible.

I was talking to a farmer from Southwestern Ontario last month—he’s investing in a new robotic milking system, expanding his quota, and bringing his son into the operation. That kind of generational transition becomes really difficult when you can’t predict what your income will be from year to year.

And speaking of the next generation… this might be the most telling statistic of all. Less than 6% of Australian dairy farmers are under the age of 35. That’s not sustainable. That’s an industry aging out without attracting young people. Meanwhile, Canadian agriculture programs and the stability of supply management continue to draw young farmers into the industry.

The Technology Factor: Why Stability Enables Innovation

One thing that really strikes me about the Australian experience is the interaction between technological advancement and market instability. You’d think that more competitive pressure would drive faster innovation, but what I’m seeing suggests the opposite might be true.

When farmers are constantly worried about whether they’ll be able to cover their costs next month, they become very conservative about major investments. Sure, they’ll adopt technologies that offer immediate payback, but the kind of long-term capital investments that really transform operations—automated milking systems, precision feeding equipment, comprehensive herd management systems—those become much riskier propositions when your milk price can swing 30% or more year-over-year.

Canadian farmers, with the price stability that supply management provides, can take a longer view. They can invest in technologies that might take three or four years to pay off, knowing that their revenue stream will be there to support the investment.

I’ve seen this firsthand, visiting farms in both countries. The Australian operations that survived and thrived tend to be those that already had significant capital reserves before deregulation took effect. The smaller farms that might have benefited most from newer technologies often couldn’t afford the risk of taking on debt for major upgrades, given their uncertain future income.

Regional Differences: Why One Size Never Fits All

Another lesson that stands out from the Australian experience is how deregulation affected different regions in varying ways. Queensland dairy farmers, who market milk premiums had protected, got hit especially hard—farm numbers there dropped by over 80%. New South Wales saw similar devastation.

Meanwhile, Victorian farmers, who were already operating primarily in the export/manufacturing milk market, initially saw some benefits. They had lower cost structures and were better positioned for the global market.

But what’s interesting about that geographic divide—it wasn’t just about efficiency or natural advantages. Queensland and NSW farmers had built their operations around a different market structure. They had smaller herds, focused on fresh milk for urban markets, and operated on different land bases. When the rules changed overnight, they couldn’t just flip a switch and become export-oriented operations.

This is something we need to keep in mind here in North America as well. A dairy farm in Vermont operates differently from one in Wisconsin or California, not just because of climate and land costs, but also due to market structures, processing infrastructure, and regulatory environments. Policies that work in one region might be disastrous in another.

Canadian supply management recognizes this reality through provincial marketing boards that can adapt to local conditions while maintaining national principles. It’s not perfect, but it acknowledges that dairy farming isn’t the same everywhere.

The Debt Trap: When Efficiency Requires Leverage

One of the most concerning trends in post-deregulation Australia has been the explosion in farm debt. Average debt per dairy farm more than doubled in real terms from $346,000 in 1999-2000 to $861,500 by 2014-15, and it’s continued climbing since then.

| Period | Average Farm Debt | Effective Hourly Wage | Farms Covering Full Costs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999-2000 | $346,000 | Not tracked | Majority profitable |

| 2014-15 | $861,500 | $2.46 (worst periods) | Unknown |

| 2015-16 | Not specified | Below minimum wage | Only 28% |

| 2022-23 | Higher (continuing trend) | Variable | Majority struggling |

Now, some debt can be good debt, right? Investing in productivity improvements, expanding operations, and upgrading facilities. But when you’re borrowing just to maintain competitiveness in an increasingly difficult market, that’s a different story.

In Australia, farms needed to become larger and more capital-intensive just to survive, but market volatility made it incredibly risky to take on the debt required for that expansion. It created this catch-22 where you couldn’t compete without investing, but investing was increasingly dangerous.

Canadian farmers, with more predictable income streams, can manage debt more strategically. They can plan expansions around known revenue projections rather than relying on the market to cooperate.

The Labor Crisis: When Young People Don’t See a Future

This might be the most troubling long-term consequence of Australia’s deregulation experience—the demographic crisis. With fewer than 6% of farmers under 35, and farm debt levels that require massive capital investments just to get started, young people are increasingly seeing dairy farming as a dead end rather than an opportunity.

I’ve spoken with agricultural educators in Australia, and they describe a generation of rural children who grew up watching their parents struggle with volatile prices, mounting debt, and constant uncertainty. Even kids from farm families often decide it’s not worth the risk.

The labor shortage isn’t just about family succession either. Hired labor has become increasingly difficult to attract and retain, as farms struggle to offer job security or competitive wages due to margin pressure.

Canadian farms, although not immune to labor challenges, continue to attract young farmers and farm workers because the industry offers more predictable career paths. When a farm can project its income three to five years out, it can make commitments to employees that become impossible under volatile pricing.

| Year | Event | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | National Competition Policy implemented | Review of all regulations restricting competition |

| 1997-98 | Market milk premium: 21¢/L higher than manufacturing | Direct wealth transfer: $311M annually to farmers |

| July 1, 2000 | Full deregulation begins | State Marketing Authorities abolished |

| 2000-2008 | Dairy Industry Adjustment Program | $1.92B in transition funding via 11¢/L levy |

| 2001-02 | Peak milk production: 11.3B liters | Never exceeded again in 25 years |

| 2011 | $1/L milk price war begins | Coles, Woolworths devalue product |

| 2020 | Dairy Code of Conduct introduced | Partial re-regulation admits market failure |

Practical Steps for Today’s Farmers

Alright, enough policy analysis—what can you actually do with this information on your farm right now?

Calculate Your Real Hourly Wage: Take your net farm income last year and divide it by the total hours you and your family put into the operation. Include everything—milking, feeding, fieldwork, bookkeeping, maintenance. If that number makes you uncomfortable, you’re not alone. Use it as a baseline for making decisions about labor efficiency and income diversification.

Stress-Test Your Operation: Model what would happen to your cash flow if milk prices dropped 20% for six months. How about if feed costs increased 30%? Australian farmers who survived deregulation were those who had built financial cushions for exactly such scenarios.

Invest in Flexibility: Technologies and management practices that allow you to adjust quickly to changing conditions become more valuable in volatile markets. This might mean variable-cost feed systems rather than fixed infrastructure, or diversified income streams that aren’t entirely dependent on milk prices.

Build Relationships Beyond the Farm Gate: Whether it’s processor relationships, banker relationships, or connections with other farmers, social capital becomes crucial when markets get turbulent. Australian farmers who were plugged into cooperative networks or had strong relationships with processors fared better than those with isolated operations.

Document Everything: Keep detailed records not just for tax purposes, but for strategic planning. Understanding your cost structure down to the cents per liter gives you real power in pricing negotiations and investment decisions.

Regional Strategy Matters: A farm in Prince Edward Island faces different challenges than one in Alberta or Wisconsin. Tailor your risk management and investment strategies to your specific regional conditions, including climate patterns, processing infrastructure, and local market dynamics.

Looking Forward: The Canadian Advantage

As I write this in 2025, Canadian dairy farmers are operating in an increasingly complex global environment. Trade pressures, climate change, technological disruption, shifting consumer preferences—all creating uncertainty and opportunity in equal measure.

However, we’re addressing these challenges from a position of relative strength, thanks in large part to supply management providing stability in an inherently volatile business. That stability isn’t just about guaranteed prices—it’s about being able to plan, invest, innovate, and pass farms to the next generation with confidence.

The Australian experience shows us what we have to lose. It also shows us that once you dismantle regulatory frameworks that provide stability, rebuilding them is incredibly difficult. The processors and retailers who benefited from deregulation have little incentive to give up their newly acquired market power.

Australia’s 2020 Dairy Code represents partial reregulation—an attempt to address the worst abuses without returning to the previous system. However, it’s a significantly weaker framework than what existed before deregulation, and it emerged only after considerable damage to farm families and rural communities.

Final Thoughts: Learning Without Repeating

So here we are, 25 years after Australia’s great dairy experiment began. The results are mixed at best—some remarkable individual farm success stories, but an overall industry that’s smaller, more concentrated, more indebted, and more vulnerable than before.

The lesson isn’t that markets are bad or that regulation is always good. It’s that the design of agricultural policies has consequences that ripple far beyond farm gates, and that stability and sustainability sometimes matter more than short-term efficiency.

As Canadian dairy farmers, we have something valuable—a system that provides the predictability needed for long-term planning and investment while still allowing for innovation and growth. It’s not perfect, and it will need to evolve as conditions change, but the Australian experience shows us what we could lose if we’re not careful.

The next time someone argues that “freeing the market” will solve agriculture’s problems, perhaps we should ask them to explain what happened to those 8,000 Australian dairy families who discovered that the market wasn’t particularly interested in their freedom.

Because at the end of the day, this isn’t about economics textbooks or policy theories. It’s about real farms, real families, and real communities. And sometimes, the most efficient market outcome isn’t the best human outcome.

Keep milking, keep learning, and keep fighting for the systems that work—because once you lose them, getting them back is a whole lot harder than keeping them in the first place.

The lesson? Don’t just get bigger. Get smarter. Your feed efficiency and genetic program could be the difference between thriving and just surviving.

Which aspect of Australia’s dairy struggles—farm consolidation, mounting debt, or community collapse—do you think poses the biggest threat to North American dairies? Share your thoughts below!

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- Scale smart, not just big: Australia’s survivors averaged 534 cows per farm (up from 168), but success came from genomic testing that improved feed conversion by 15-20%—start screening your replacement heifers now

- Price volatility is real: When markets crashed, farmers lost 19 cents per litre overnight—build your buffer with feed efficiency programs and genetic selection for resilience traits

- Tech pays off: Farms using precision feeding and genomic data improved profitability by 8-12% annually—invest in herd management software and genetic testing this season

- Youth crisis hits hard: Only 6% of Aussie farmers are under 35—use stable planning tools like genomic breeding programs to create succession opportunities that actually work

- Market power matters: When five processors controlled 79% of milk volume, farmers got squeezed—join cooperative purchasing groups and leverage genetic data to negotiate better contracts

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

Look, I just finished reading this massive report on what happened down in Australia after they deregulated their dairy industry 25 years ago. The numbers will shock you—65% of farms disappeared, yet the survivors tripled their herd sizes. Here’s what’s wild though: total milk production actually dropped 26% despite all that “efficiency.” Some farmers were effectively earning $2.46 an hour during the worst stretches. Yeah, you read that right. While consumers saved money on milk, processors and retailers grabbed most of the profit. The ones who made it through? They had to get smart about genomic selection, feed optimization, and managing massive debt loads. Global research backs this up—farms using advanced genomic testing and precision feeding are the ones still standing. Bottom line: if you’re not using these tools to maximize what you’ve got, you’re playing a dangerous game.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Profit and Planning: 5 Key Trends Shaping Dairy Farms in 2025 – This strategic analysis provides a forward-looking perspective on global market trends and how to financially stress-test your operation. It reveals how to use component-rich exports and strategic debt management to protect profits from future market volatility.

- Your 2025 Dairy Gameplan: Three Critical Areas Separating Profit from Loss – Get tactical with this guide on practical, day-to-day changes. It offers actionable tips on optimizing feed management, using methionine, and nailing transition cow protocols to deliver measurable improvements in milk components and herd health.

- The Future of Dairy Farming: Embracing Automation, AI, and Sustainability in 2025 – Explore the cutting edge of dairy technology with this deep dive into automation and AI. It details how whole-life monitoring and precision agriculture systems reduce labor costs and boost efficiency, showing how stable income enables strategic tech investments.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!