From a 14-cow classification round in Quebec to Alberta’s first 95-pointer—here’s who earned the industry’s hardest win

Fourteen Excellent cows in a single classification visit. That’s 14 handshakes. Any breeder who’s waited for that classifier to finish walking knows exactly how that moment felt for Micheret.

That’s the kind of result that earns a Master Breeder shield—and it’s just one story from the 21 Canadian operations Holstein Canada honored this year.

The Master Breeder designation isn’t handed out for one great lactation or one banner at a show. It evaluates your herd over a rolling 16-year window. Sixteen years of stacking high production, superior type, and cows that don’t quit—through milk price crashes, feed spikes, and every sire trend that came and went. These 21 herds kept delivering.

“Tonight is all about dedicated breeders, outstanding cows, and a legacy of excellence built generation by generation,” Holstein Canada President Jill Cote said during the reveal ceremony.

By the Numbers

- 21 shields awarded across five provinces

- 14 Excellent cows in one classification round (Micheret)

- 106 Excellent cows bred since 2005 (Crestomere)

- 16 consecutive VG or EX generations (Nauly)

- 99 HPI maintained for 16 straight years (Saintour)

- 74 Excellent cows underpinning a second shield (Nauly)

Want to meet these winners? The 2026 National Holstein Convention runs this April in British Columbia. Registration is open now.

Quebec Takes 12: The Province That Breeds Different

Quebec claimed more than half the shields this year—12 of 21. But the numbers don’t tell you much. The strategies behind them do.

Micheret: 14 Excellent Cows, One Classification Round

Balanced breeding between conformation and production has always been Micheret’s philosophy. The payoff came during a classification visit that produced 14 Excellent designations in a single round. That wasn’t luck. That was decades of breeding decisions finally showing up on the same day.

Hectare (Roxton Pond): The Tabasco Legacy — Second Shield

Some herds are built on one phenomenal cow family. For Hectare—earning their second shield—that foundation is Tabasco. Her two daughters have earned the Excellent designation a combined 10 times. When a cow family produces that consistently, you build your whole program around it.

Dessauges (Farnham): From Crossbred to 60+ Excellent

This one’s a complete rebuild. Dessauges started as a crossbred operation in the early 1990s. By the early 2000s, they’d transitioned to 100% purebred Holsteins. Their first Excellent cow came shortly after—an 11-year-old with eight calves behind her. Today, the herd boasts more than 60 Excellent cows. That kind of transformation doesn’t happen by accident.

Desross (Sainte-Flavie): The 25-Embryo Investment That Changed Everything

Desross purchased 25 top-quality Semex embryos, resulting in 11 females with strong first-lactation milk yields. Combined with genetic testing and classification, that embryo investment didn’t just provide momentum—it fundamentally rewrote their genetic trajectory. The herd hasn’t looked back.

Saintour: 16 Years at HPI 99

Saintour adopted a breeding strategy focused on animal health, fertility, and productivity. The payoff? A Herd Performance Index of 99 for 16 consecutive years—including a first-place national ranking in Canada in 2010. You don’t hold 99 for 16 years without intention.

Nauly: Second Shield, 74 Excellent Cows, 16 Generations of VG or Better

Nauly is back for their second Master Breeder shield. They’re sitting on 74 Excellent cows with 16 consecutive generations classified Very Good or Excellent. Their formula: strong cow families, embryo transfers on top bloodlines, and patience. “Believe in your goals,” was their advice during the ceremony. Good year for them.

Ringo (Rouville): International Recognition for Productivity

Bull selection and classification drive everything at Ringo. They use classification reports as their progress report card. The approach paid off with recognition by Holstein International as one of the most productive herds—global acknowledgment, not just national.

Boisvert

Boisvert worked hard as a family with a clear breeding vision to develop balanced, productive cows. They combine quality forage with strong genetics, and they’ve built a group of cows they actually enjoy working with every day.

Mibois

Mibois focuses on developing beautiful, productive cows that they look forward to working with each day. Being named a Master Breeder finalist was, in their words, “a wonderful and completely unexpected surprise.” Sometimes the award finds you before you expect it.

Roclairson

Roclairson uses a focused breeding program guided by classification to refine conformation and improve reproduction. Their advice: “Seek guidance, but always trust your own judgment.”

Rochelet

Rochelet remains committed to high-performance genetic lines with an unwavering focus on excellence. Steady, strategic, consistent.

Chevrier

Chevrier relies on genetics and classification as core pillars of their management strategy, complemented by supervised milk testing and a strong emphasis on proper nutrition. When they got the surprise phone call during the ceremony, you could hear the emotion in their voices.

Ontario’s Five: Red & White Bets, Classification GPS, and the Three C’s

Ontario brought five shields home. Each operation took a different path to get there.

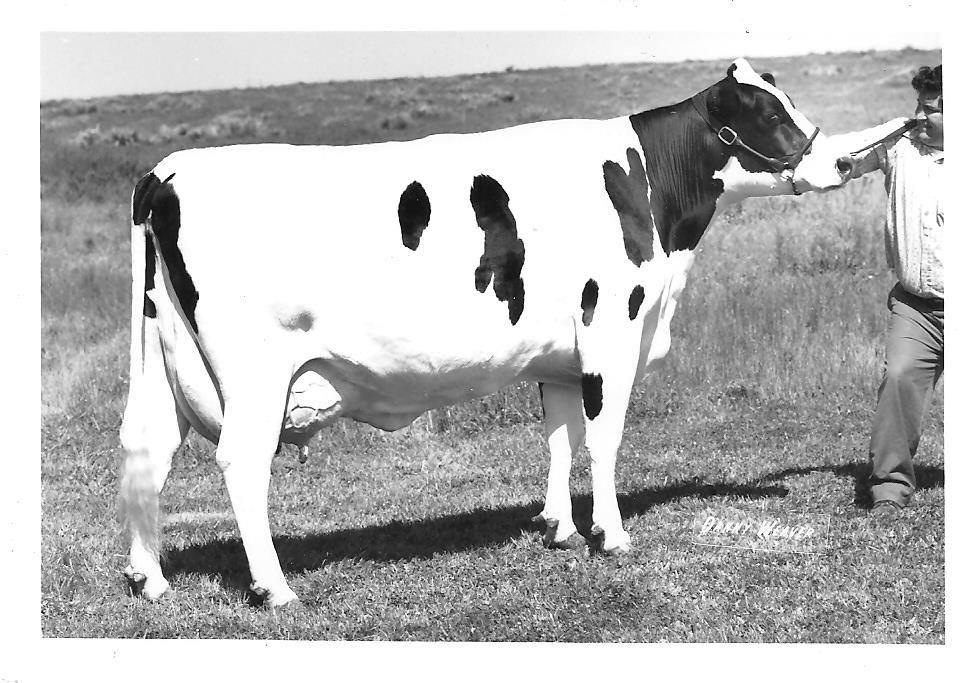

H-Bridge (Park Hill): All In on Red & White

Genetics and classification have always guided H-Bridge’s decisions. But their defining move was the transition to a 100% Red & White herd. In an industry where black-and-white still dominates showrings and semen catalogs, H-Bridge proved that specialized genetic focus can deliver national-level excellence.

“We can’t blame them for switching to reds,” the hosts joked during the reveal. The room agreed.

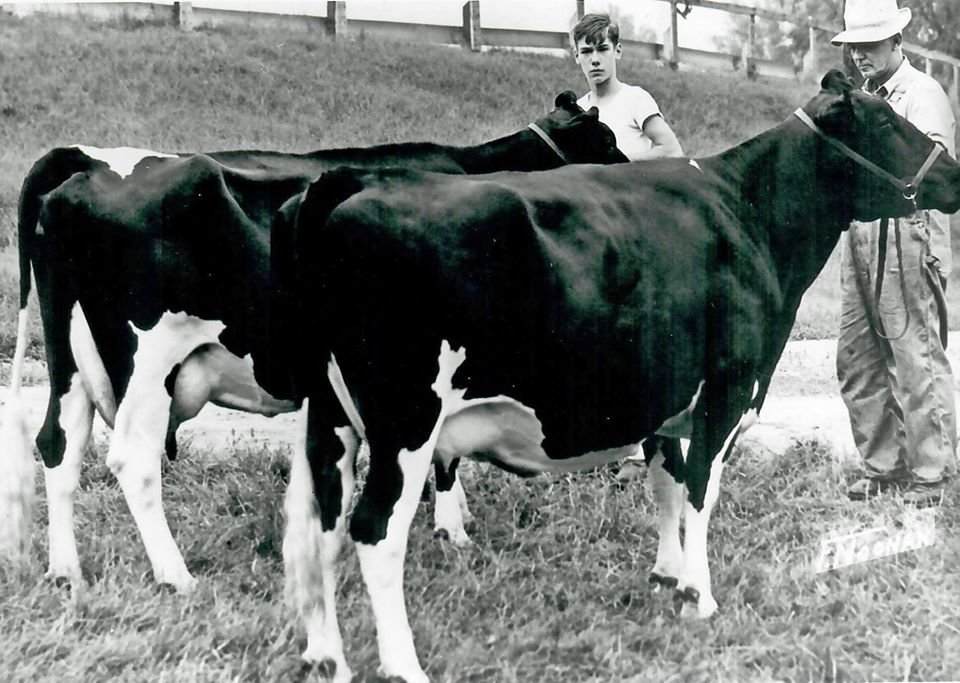

Vonburg (Woodstock): Excellent Daughters from Excellent Mothers

Vonburg focuses on cow families and sire proofs to create matings that produce long-lasting, profitable cows. Their most memorable milestone? Seeing Excellent daughters come from Excellent mothers—proof that their evaluation process actually works across generations. Exactly what they wanted.

Hiddenspring (Elmira): Learning from Classifiers and Adapting

Hiddenspring remained committed to its breeding strategy, focusing on increasing production while learning from classifiers and adapting to industry trends. That agility—knowing when to hold steady and when to adjust—separates breeders who plateau from breeders who keep climbing.

Birdolm (Rockwood): Classification as the Breeding GPS

Birdolm uses classification to guide thoughtful mating decisions, focusing on continuous improvement. Cows that stick around longer and milk harder. That’s money.

Eastedge (Springfield): Crops, Cows, and Comfort

Eastedge lives by the Three C’s: Crops, Cows, and Comfort. Grow good crops. Breed good cows. Provide excellent comfort.

“The Master Breeder shield is an award that comes from doing your best job each day,” they said during the ceremony. Their advice to the next generation? Focus on those three things. Everything else follows.

Alberta’s Two: Data-Driven Breeding and a 95-Pointer in 2025

Mosnang: Every Data Point, Every Generation

Genetics drives Mosnang’s passion for dairying and their commitment to continually breeding better cows. They use genetics, classification, registration, DHI, genomics, and cow families to evaluate, track, and improve their herd generation after generation. If there’s data available, Mosnang is using it.

When Holstein Canada called to announce the win, Mosnang picked up from the tractor. Farm life doesn’t stop for phone calls—you just take them wherever you are.

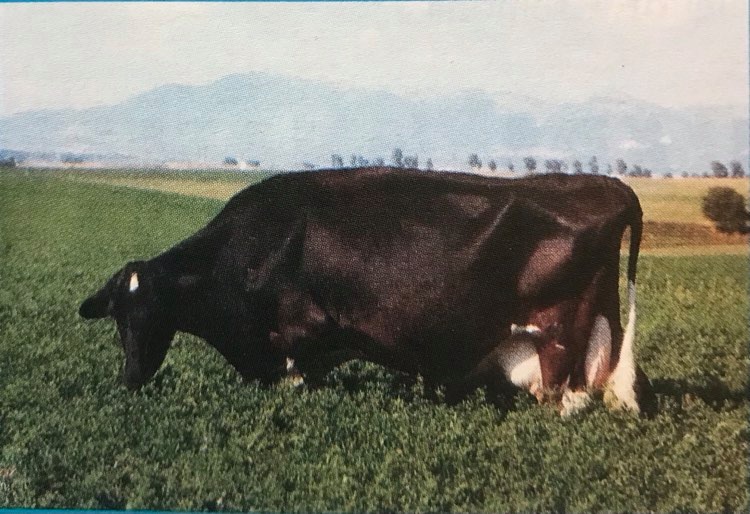

Crestomere: 106 Excellent Cows and Their First 95-Pointer

The Simonton family at Crestomere picked up the phone mid-chores when Holstein Canada called. You could hear the barn in the background.

Achieving Master Breeder status has always been their goal. In 2018, they moved from a tie-stall barn to a robotic facility. That transition, combined with sand bedding, increased cow comfort and longevity. Since 2005, they’ve bred 106 Excellent cows. And in 2025, they brought in their first 95-point cow.

That’s a year to remember.

Manitoba’s Shield: Missiontrail (Woodlands)

Missiontrail focuses on genetics to improve their next generation, emphasizing high production, functional type, and longevity. Every classification sheet is a report card—and they actually use it.

Nova Scotia’s Shield: Bokma (Shubenacadie)

Bokma is a third-generation, seven-robot dairy focused on producing elite, long-lasting cows with high production and type. They successfully bridged the gap between traditional breeding principles and modern robotic technology.

The Master Breeder goal guided their decisions. The robots didn’t change their breeding philosophy—they just changed how the cows get milked. That’s the balance.

What Past Winners Want You to Know

Chris McLaren of Larenwood (Drumbo, Ontario—2019 winner) joined the ceremony to share what he learned on the way to his shield. Worth hearing.

On the decision that made the difference:

“25 years ago, when I came home to farm, I convinced my dad that we are going to invest the same amount of money in genetics, but I was going to learn to breed cattle, and we’re going to put that money into great bulls. We slowly progressed over many years to producing better and better cattle, and it helped to accelerate our journey.”

On their 70-year closed herd strategy:

“Our simple goal is to match to make the daughters better than the mothers, and to slowly work away generation after generation and invest in our great families. Investments that don’t seem like you’re doing much at the time—but when you look, and it slowly builds over years and years, you’re getting a lot out of it.”

On what he’d tell tonight’s winners:

“Be patient and determined with your goals. We’re proof that long-term vision and goal-setting—you can achieve the things you dream of. Listen to neighbors and industry personnel, draw on their experience and wisdom. And most of all, keep in mind what is best for the cow in all the things you do. What is best for her in mating and breeding, and in health, facilities, and prevention? All those things will eventually get you where you want to go.”

Holstein Canada’s Vision: Protecting Genetic Integrity

Greg Dietrich, CEO of Holstein Canada, outlined the association’s direction during the ceremony.

“For 144 years, Holstein Canada has earned the trust of dairy farmers. That legacy matters,” Dietrich said. “But our future depends on how well we deliver on our strategies.”

He outlined four pillars: member and producer engagement, strong leadership and governance, industry partnerships, and innovation and research.

On the association’s role as the industry evolves: “We do that by protecting the integrity of both genetics and data, adopting new tools where they improve service, and ensuring information remains practical and relevant at the farm level. Just as importantly, we must continue to represent and connect breeders with a rapidly changing dairy ecosystem.”

The 2026 National Convention: BC This April

The 2025 Master Breeders will be honored at the National Holstein Convention in British Columbia this April. The theme is “Spirit of the West.”

Tammy Oswick, Holstein Canada’s bilingual event specialist, shared what’s planned:

- Taste of BC: Local fare and fireside chats

- Farm Tours: See BC operations firsthand

- National Show: Heritage Park in Chilliwack, BC

- Grouse Mountain Reception: A gondola ride to the President’s reception—”It will definitely be a night to remember,” Oswick said

“Convention week is a time to make new connections and reconnect with others while enjoying the beauty of the area we’re in and celebrating the success of our members,” Oswick said. “It’s really a memory in the making.”

Registration is open now. Book your hotel rooms early.

2025 Master Breeder Recipients

| Herd Prefix | Province | Key Achievement/Focus |

| Micheret | Quebec | 14 Excellent cows in one classification round |

| Hectare | Quebec | Second shield; Tabasco cow family |

| Boisvert | Quebec | Family-focused balanced breeding |

| Dessauges | Quebec | Crossbred to 60+ Excellent purebreds |

| Desross | Quebec | 25 Semex embryos transformed trajectory |

| Saintour | Quebec | HPI 99 for 16 years; #1 Canada 2010 |

| Nauly | Quebec | Second shield; 74 EX, 16 VG/EX generations |

| Mibois | Quebec | Beautiful, productive cow development |

| Roclairson | Quebec | Classification-guided breeding program |

| Rochelet | Quebec | High-performance genetic lines |

| Chevrier | Quebec | Genetics, classification, nutrition focus |

| Ringo | Quebec | Holstein International productivity recognition |

| H-Bridge | Ontario | 100% Red & White transition |

| Vonburg | Ontario | Excellent daughters from Excellent mothers |

| Hiddenspring | Ontario | Production growth via trend adaptation |

| Birdolm | Ontario | Classification-guided longevity |

| Eastedge | Ontario | “Three C’s”: Crops, Cows, Comfort |

| Mosnang | Alberta | Data-driven: DHI, genomics, classification |

| Crestomere | Alberta | 106 EX since 2005; first 95-pointer in 2025 |

| Missiontrail | Manitoba | Classification as a report card |

| Bokma | Nova Scotia | Third-generation, seven-robot dairy |

Provincial breakdown: Quebec 12* – Ontario 5 – Alberta 2 – Manitoba 1 – Nova Scotia 1

Congratulations to all 2025 Master Breeder recipients. See you in BC this April.

Holstein Canada acknowledges the generous support of industry partners: Semex, Blondin Sires, and Zoetis.

For convention registration and Master Breeder Gala information, visit Holstein Canada’s website.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- 21 farms. 16 years. The call came mid-chores. That’s what it takes to earn Canada’s hardest breeding award—no shortcuts, no catalog genetics, just cows that kept milking, classifying, and showing up pregnant.

- Quebec claimed 12 shields and made it look easy. Micheret dropped 14 Excellents in one classification visit. Nauly stacked 74 Excellents across 16 straight VG/EX generations. Saintour held an HPI of 99 for 16 consecutive years. The province breeds differently.

- Classification is still the only report card that pays. Every winner credited classifiers—not pedigree hype, not sale prices, not Instagram likes—as the primary feedback loop for mating decisions.

- Robots don’t change what wins. Cows do. Bokma runs seven robots in Nova Scotia. Crestomere switched from tie-stalls in 2018 and just scored their first 95-pointer. Both earned shields by keeping the cow at the center of every facility upgrade.

- BC. April. 21 shields. One stage. The National Holstein Convention’s Master Breeder Gala turns those mid-chores phone calls into the kind of handshakes breeders talk about for decades.

Executive Summary:

For 21 farms across Canada, the Master Breeder phone call finally came—often right in the middle of chores—after 16 years of stacking cows that milk last, and classify the way they were bred to. Quebec owned the night with 12 shields, from Micheret’s 14-Excellent-cow classification visit to Nauly’s 74 Excellents and 16 straight VG/EX generations. Ontario’s five winners leaned on cow families and classifiers as their GPS, while Alberta’s Mosnang and Crestomere proved you can mix genomics, robots, and 106 homebred Excellents into the same story and still have it start in a tie-stall barn. Manitoba’s Missiontrail and Nova Scotia’s Bokma showed that smaller provinces can still build big-time cows by treating every classification sheet like a report card and every robot as just a different way to milk the same kind of cow. On the big-picture side, CEO Greg Dietrich laid out Holstein Canada’s plan to protect the integrity of both genetics and data, and past winner Chris McLaren reminded breeders that great bulls, closed herds, and cow-first facilities still win if you give them enough years. All 21 herds will step onto the stage at the 2026 National Holstein Convention in British Columbia, where the “Spirit of the West” will turn those mid-chores phone calls into the kind of night breeders remember for the rest of their careers.

Continue the Story

- The Magic Behind Larenwood Farms: How Chris McLaren is Redefining Dairy Excellence — Chris McLaren’s advice to the 2025 winners came from somewhere real. This profile unpacks the 70-year closed herd, the 2019 shield, and the philosophy that turned a sixth-generation Ontario farm into Canada’s Best Managed Herd. If his words during the ceremony resonated, this is the full story behind them.

- The Great Holstein Shakeup: How 16 Years Rewrote Breeding Rules — The Master Breeder shield evaluates herds over a rolling 16-year window. This piece explains what happened to Holstein breeding during that same timeframe—genomics cut generation intervals by 76%, selection shifted toward functional traits, and the “super-sire” model collapsed. The forces these 21 winners navigated, mapped out.

- Bosdale Farms: The Legacy Behind Canada’s Most Excellent Cows — Crestomere bred 106 Excellents since 2005. Bosdale has 415. This multi-generational Ontario family walks a parallel path—patient breeding, cow-family obsession, and the belief that functional conformation outlasts every trend. If Crestomere’s story inspired you, Bosdale shows what another 50 years of the same philosophy can build.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!