After a number of U.S. Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, audits of dairies in New Mexico and Texas last year, Dr. Ellen Jordan, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service dairy specialist in Dallas, said the industry is working to help dairies get laborers properly documented.

U.S. Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, audits of laborer paperwork on dairies has increased in New Mexico and Texas in the past few years. (Texas A&M AgriLife photo by Kay Ledbetter)

Tiffany Dowell Lashmet, AgriLife Extension agricultural law specialist in Amarillo, led an employee immigration panel discussion on “Navigating the Dairy Workforce Crisis” recently at the High Plains Dairy Conference in Amarillo.

“Immigration is an important issue for all of agriculture, but particularly for the dairy industry,” explained Lashmet. “The vast majority of dairy owners want to comply with the law when hiring employees, so ensuring they know exactly how the law works and are educated on what their rights and responsibilities are is critical.”

Jordan and Lashmet recently wrote a publication, “The Difference between an ICE Raid and an ICE Audit: Are You Prepared?” which can be downloaded from the AgriLife Bookstore at: http://bit.ly/2iEwwLc.

“What we are trying to do is identify laborers and get them employed according to U.S. regulations, with an emphasis on what should be done to make sure they have proper documentation,” Jordan said.

“Traditionally a large portion of our workforce has been immigrants,” she said. “So producers need to know the changes in immigration policy and procedures.”

Jordan said the human resources panel was designed to address not only how to deal with ICE, but how to bring new employees on board with proper training so they are effective at doing their job and integrated into the farm team.

Sarah Thomas, a lawyer with Noble and Vrapi Immigration Attorneys in Albuquerque, New Mexico, said during the panel discussion that I-9 forms are required for every employee, regardless of race or status.

She said when the subpoena for an audit or notice of inspection is served at the dairy, there are several things all employees should know and the dairy should have trained them on.

“Designate who will talk to the agents and who will sign for the subpoena,” Thomas said. “You don’t want someone who doesn’t know what is going on or the time frame they have to comply.”

She said the employer has 72 hours from the time they receive the subpoena to gather data, during which time an employer should consider consulting an attorney and thoroughly reviewing all of their I-9 documents. Once the documents are turned over, the dairy will generally receive a letter of technical violations and have 10 days to show good faith and try to comply.

“We recommend you have a uniform policy with regard to copying documents presented by an employee completing an I-9 form by either taking or not taking copies of supporting documents,” Thomas said. “What you do for one employee, do for all employees.”

If an employer has taken all documents in good faith and complied with the record-keeping rules, she said, they are not liable. But in the end, if a worker is not able to be accurately documented, their employment must be terminated as it is illegal to knowingly employ someone who is not authorized to work in the U.S.

Thomas offered some suggestions on how to prepare and respond to an ICE visit:

- Have a procedure in place and employees trained on what to do if ICE shows up at the dairy.

- Obtain a copy of any subpoena or search warrant and send it to an attorney for review.

- Do not voluntarily waive the 72-hour time period for producing I-9 documents.

- Don’t allow officers into non-public areas without a search warrant granting them such access.

- Don’t overtly share information that is not required.

- Mark areas “Employees Only.”

- Do your own audits internally to ensure I-9 documentation is in order.

Jordan said the number of on-farm employees in the dairy industry are generally figured at one for every 100 cows. So, in Texas, there’s an estimated workforce of 4,000, she said, and that doesn’t include the allied industries, such as veterinarians, technicians, nutritionists, milk truck haulers and others.

She said the labor force on dairies is continually changing, which equates to constant processing of paperwork.

While Jordan said the pay is good and that is what attracts the workers, it is physical labor and that can sometimes be the reason for the revolving door.

“The work is outdoors, and workers have to adjust and decide if they want to do that,” she said. “Many new employees start in the milking parlor and that is repetitive work. Also many workers have not done farm work at all, so they have to decide if that is a culture they want to be involved in.”

Also, if the owners and managers are able to engage the workers and help them learn their position to become a team member, it is more effective, Jordan said.

“Communication and building trust are key points of workforce management,” she said. “Most of our workers are coming without skills and those skills need to be developed on the farm. We need effective training so the workers are comfortable at their job and want to stay.”

Source: animalscience.tamu.edu

Knowing the total solids content of milk replacer fed to calves is critically important, yet few producers or calf managers know their total solids content or how to calculate it.

Knowing the total solids content of milk replacer fed to calves is critically important, yet few producers or calf managers know their total solids content or how to calculate it. Legend has it there’s a barn full of cows in Pennsylvania which refuse to eat anything but bubblegum-flavored nutritional pellets.

Legend has it there’s a barn full of cows in Pennsylvania which refuse to eat anything but bubblegum-flavored nutritional pellets.

Many dairy farmers have followed a tradition of making contracts informally – perhaps orally and with a handshake, or in the case of a milk contract it may have been a one-pager signed on the hood of the field man’s pickup truck. But one experienced attorney is advising farmers to take a close look and see how that contract may affect them. And they should get it in writing.

Many dairy farmers have followed a tradition of making contracts informally – perhaps orally and with a handshake, or in the case of a milk contract it may have been a one-pager signed on the hood of the field man’s pickup truck. But one experienced attorney is advising farmers to take a close look and see how that contract may affect them. And they should get it in writing. Double-cropping winter annuals after corn silage harvest is increasing in popularity among dairy farmers who have found that it provides numerous benefits, including increased per-acre forage production, reduced feeding costs, better cycling of manure nutrients and improvements in the farm’s overall bottom line.

Double-cropping winter annuals after corn silage harvest is increasing in popularity among dairy farmers who have found that it provides numerous benefits, including increased per-acre forage production, reduced feeding costs, better cycling of manure nutrients and improvements in the farm’s overall bottom line.

Four keys to calf health success

Four keys to calf health success The current price of hay is a frequent question asked by callers to the area county extension offices. It is an important question to cattle producers wanting to turn a profit because hay costs represent a significant overall expense in raising cattle.

The current price of hay is a frequent question asked by callers to the area county extension offices. It is an important question to cattle producers wanting to turn a profit because hay costs represent a significant overall expense in raising cattle. Livestock manure contains beneficial soil-building ingredients and plant nutrients, but they could be wasted if the manure spreader isn’t calibrated correctly.

Livestock manure contains beneficial soil-building ingredients and plant nutrients, but they could be wasted if the manure spreader isn’t calibrated correctly. Significant advances in dry cow nutrition have been made in the last 20 years. Most recently, interest has shifted to the protein needs of transition cows. Advancements in the models for ration balancing have made it possible to estimate the metabolizable protein (MP) supply and needs of dry cows, while the use of crude protein still remains important. This gives nutritionists the opportunity to formulate diets for dry cows based on metabolizable protein and amino acids.

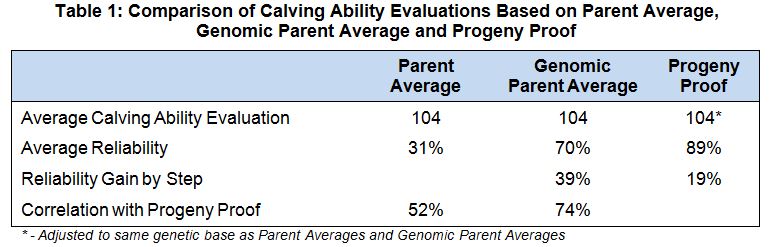

Significant advances in dry cow nutrition have been made in the last 20 years. Most recently, interest has shifted to the protein needs of transition cows. Advancements in the models for ration balancing have made it possible to estimate the metabolizable protein (MP) supply and needs of dry cows, while the use of crude protein still remains important. This gives nutritionists the opportunity to formulate diets for dry cows based on metabolizable protein and amino acids. Research could eliminate need for hormone protocols

Research could eliminate need for hormone protocols

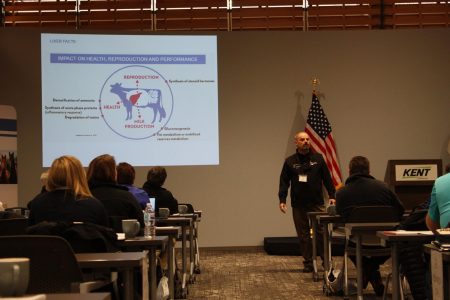

Kent Nutrition Group (KNG) hosted nearly 100 dairy producers, nutritionists, and industry specialists at their inaugural KNG Dairy School held at Kent Corporation headquarters this week. The school entitled, Dedicated to Dairy, focused on transition cow nutrition and their crucial role in a dairy’s long-term success. Industry speakers shared their latest research findings and management protocols for moving these cows into milk production.

Kent Nutrition Group (KNG) hosted nearly 100 dairy producers, nutritionists, and industry specialists at their inaugural KNG Dairy School held at Kent Corporation headquarters this week. The school entitled, Dedicated to Dairy, focused on transition cow nutrition and their crucial role in a dairy’s long-term success. Industry speakers shared their latest research findings and management protocols for moving these cows into milk production. 6 calving tips that can make a lifetime of difference

6 calving tips that can make a lifetime of difference Southwest Missouri dairy producer David Gray is one of the first in his area to use compost bedded pack barns. Cows raised using this system enjoy greater comfort, produce more milk and have fewer health problems. ( Linda Geist, University of Missouri Extension )

Southwest Missouri dairy producer David Gray is one of the first in his area to use compost bedded pack barns. Cows raised using this system enjoy greater comfort, produce more milk and have fewer health problems. ( Linda Geist, University of Missouri Extension )

Robotic or automatic milking systems (AMS) have steadily increased in popularity in the dairy industry since the installation of the first commercial unit in 1992 in the Netherlands. In 2015, the number of AMS units installed was over 25,000 worldwide. Here in Nebraska, there are two commercial dairy farms that having installed multiple AMS units, Demerath Farms (Plainview, NE) and Beaver’s Dairy (Carleton, NE). Demerath Farms installed four AMS units in February 2017 and are set up to milk 240 cows. Beaver’s Dairy began milking with five AMS units in May 2017 and is set up to milk 300 cows. Additionally, there are several other dairies that are looking into milking robots for their farm. Typically, 60 cows are milked on one robot. One robot will likely cost the producer anywhere from $150,000- $200,000.

Robotic or automatic milking systems (AMS) have steadily increased in popularity in the dairy industry since the installation of the first commercial unit in 1992 in the Netherlands. In 2015, the number of AMS units installed was over 25,000 worldwide. Here in Nebraska, there are two commercial dairy farms that having installed multiple AMS units, Demerath Farms (Plainview, NE) and Beaver’s Dairy (Carleton, NE). Demerath Farms installed four AMS units in February 2017 and are set up to milk 240 cows. Beaver’s Dairy began milking with five AMS units in May 2017 and is set up to milk 300 cows. Additionally, there are several other dairies that are looking into milking robots for their farm. Typically, 60 cows are milked on one robot. One robot will likely cost the producer anywhere from $150,000- $200,000.

Zoetis announced the addition of three calf wellness traits to Clarifide® Plus for Holsteins. The new calf wellness traits include calf livability, respiratory disease and scours. This dependable genetic information enables dairy producers to genetically improve calf health and survival within their herds, as the calf wellness trait information helps identify and select for calves more likely to survive as well as animals that are less likely to become ill due to respiratory disease and scours. Minimizing disease risk improves calf health, results in fewer treatments and lowers calf mortality — all important animal well-being considerations for producers.

Zoetis announced the addition of three calf wellness traits to Clarifide® Plus for Holsteins. The new calf wellness traits include calf livability, respiratory disease and scours. This dependable genetic information enables dairy producers to genetically improve calf health and survival within their herds, as the calf wellness trait information helps identify and select for calves more likely to survive as well as animals that are less likely to become ill due to respiratory disease and scours. Minimizing disease risk improves calf health, results in fewer treatments and lowers calf mortality — all important animal well-being considerations for producers.

America’s Dairyland is undergoing a bit of a revolution, and it has nothing to do with the words on Wisconsin’s license plate or even the size of farms.

America’s Dairyland is undergoing a bit of a revolution, and it has nothing to do with the words on Wisconsin’s license plate or even the size of farms.

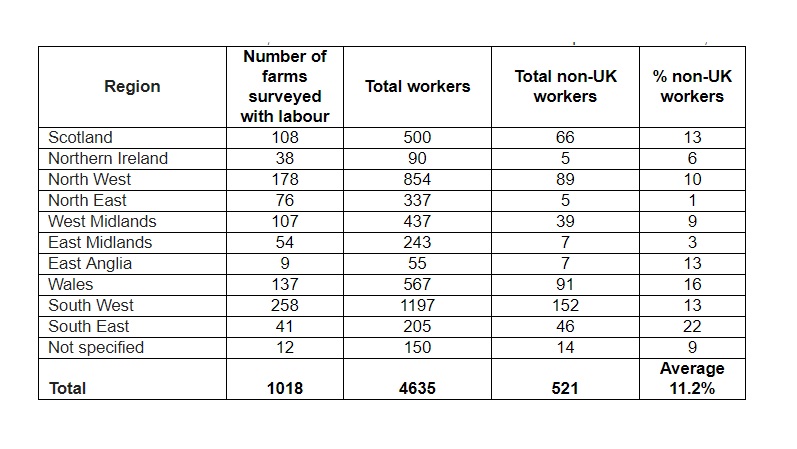

The dairy industry is concerned that a lack of skilled workers will make it unable to meet targets as the UK is responsible for a tenth of Europe’s total milk supply.

The dairy industry is concerned that a lack of skilled workers will make it unable to meet targets as the UK is responsible for a tenth of Europe’s total milk supply.

A new study in the Irish Medical Journal has found a high prevalence of work-related respiratory and upper airways symptoms among dairy farmers.

A new study in the Irish Medical Journal has found a high prevalence of work-related respiratory and upper airways symptoms among dairy farmers. Antibiotic dosages are determined by individual cattle body weight.

Antibiotic dosages are determined by individual cattle body weight.