On many dairies, losing a few calves a year is not regarded as a big financial loss and that, in fact, is probably right. The things which are costing the enterprise money are the related but unseen financial effects of clinical and subclinical disease in the surviving calves.

When farmers are asked to estimate the cost of dead calves, most will list the obvious losses:

- Farmgate value of the calf.

- Value (if any) of the feed the calf consumed before death.

- Labour costs to rear them to the time the calf died.

- Veterinary costs, including drugs.

My experience and that of other large-scale calf rearers is that, as a generalisation, for every dead calf, there are about five sick ones. In this context, I would define a sick calf as one which needs or receives supportive therapy of some sort – tube feeding, isolation, electrolytes or drugs.

For every five sick calves there are probably 25 diverting nutrients from growth into immune system function to defend their bodies against infection, i.e. staying healthy but in doing so have reduced weight gains/kilogram of feed consumed.

It is the related illness, poor feed conversion efficiencies and sub-optimal growth rates in surviving calves that cost far more money than the value of the dead calves.

For example, it is quite possible that a group of calves under stress will consume double the amount of grain to reach a target weight when compared with a group of unstressed calves. This alone is an unnecessary cost but when coupled with the other unseen costs linked to poor early life growth rates, such as reduced lifetime feed conversion and failure to reach genetic potential for milk production, the financial impost associated with the cost of dead calves can be huge.

The figures I have given are not graven in stone; they will vary from farm to farm and year to year. The point is that by scrimping on rearing costs, calf health and growth rates will be jeopardised and the long-term financial losses will far outweigh any money saved in the short term.

Long-term productivity will certainly be compromised and animal welfare outcomes will not meet consumer expectations.

Often farms have no easily accessible factual record of the number of deaths that occur in a particular year. Guesstimates of losses are often later proven to be under-estimates.

The death of only 2 per cent of heifers reared is often viewed as a really good result. If one takes the approximate figures I have given above, two dead calves are linked to 10 sick calves and 50 that are not ill but which have enough of an immune challenge to decrease their feed conversion efficiency.

It is important to remember that I am not using these figures as facts. They are just approximations of what may be happening; on some farms, the results will be more favourable, on others the results will be much worse.

What I am trying to illustrate is that the actual cost of any dead calves can be a drop in the ocean A range of factors can cause an exponential increase in these costs on dairies rearing higher number compared with the real, on-going losses sustained, but not seen, by the enterprise.

Which calves should be included in the mortality statistics? From the point of view of improving calf management, it is generally accepted that if a calf is brought in from the calving area to the rearing area and is expected to live, i.e. it is tagged and treated normally for the first few hours of life but subsequently dies, that is should be counted as a dead calf.

Usually counting would cut off at 12 weeks, once a calf has been weaned but since some farms still have 12-week-old heifers on milk, maybe those farms should use a timeframe of weaning plus four weeks as the cut-off point for inclusion in mortality statistics.

Whatever upper age limit is chosen, it is important to be consistent from year to year. It is also important to include a few weeks post weaning in the statistics as poor weaning practices can result in post-weaning deaths, which still relate to poor calf management pas those deaths are not a result of poor calf management practices.

Stillbirths and calves that are obviously ill or deformed at birth should not be counted. A note should be kept of these deaths, though, as they may be a result of herd health problems.

Now, let’s consider what is an acceptable mortality rate. In an average beef herd in southern Australia, and I have managed several, it is pretty unusual to lose more than 1 per cent of calves, particularly in the first 2-3 months of life. This is what nature can do – 1 per cent or less.

Therefore, if dairy calves are to be removed from their natural mothers and raised by human surrogate mothers, those surrogates should have less than 1 per cent deaths as the goal. Achievinfor animal welfare this will have a positive financial impact on the business and will allow the farm to meet consumer expectations.

Money spent on raising heifers does not give a return until those heifers enter the herd. It is important to remember that, providing the money is spent proactively on raising healthy calves, not reactively on treating sick calves, the greater the investment, the greater the return will be.

Attempting to save money by reducing the costs of calf-feeding inputs will result in calves that do not achieve recommended growth rates and that are more likely to become ill and die.

Calves that are limit-fed will achieve low growth rates and will be on feed for much longer to achieve a target weight. Their efficiency of gain will be lower than calves that are fully fed (i.e. it will cost more to grow calves out to a target weight) and they will be far less productive cows when they enter the herd.

Add together the:

- Direct costs of increased mortality.

- Direct costs of increased sickness.

- Extra costs per kilogram of weight gain.

- Lower lifetime milk production.

- Lower lifetime feed conversion efficiency.

- Poor animal welfare outcomes.

This reveals the enterprise has a significant financial burden as well as not meeting welfare expectations.

In times of low milk prices, it is a normal survival tactic to try to cut back on every expense. The best way to economise in the area of heifers is to do a really good job.

Sick calves mean that somewhere, something is not being done well; this only adds to the costs of rearing heifers. Raising healthy calves is not any more expensive up front than doing a bad job – it just means money is spent in different areas.

Raising healthy calves may mean spending less money for a better result and it is far more satisfying than dealing with sick and dying calves.

Doing the most effective and economical job with pre-weaned calves means having:

- Excellent colostrum collection, storage and administration practices.

- Farm-specific sanitation protocols that are followed to the letter.

- Milk and grain feeding schedules that allow calves to grow at the recommended rates.

- The ability to weigh calves and to monitor the success of the calf management program.

Failure to acknowledge that an enterprise has a calf management problem will not make the problem go away; the problem will continue to drain resources from the enterprise until it is addressed.

Increasingly, high death rates are becoming not just an economic issue, which farmers can choose to ignore if they are prepared to accept the financial loss, but an issue of customer expectations. A pile of dead calves outside the calf shed is not something which the average customer would be happy about.

The good thing is that making management changes to meet consumer expectations only involves changes that reduce morbidity and mortality rates and increases growth rates and health outcomes, that is, changes that are beneficial to the enterprise.

At times when farmers are looking for ways to improve profitability, improving calf management is an area that delivers multiple benefits.

Source: The Australian Dairyfarmer

Dairy farmers will need to think about their breeding choices to ensure they have a herd capable of producing milk with higher fat content to get the best returns, a new report says. DairyNZ strategy and investment leader Bruce Thorrold released the report, which said shifts in bull breeding worth (BW) reflected an increase in the value of fat.

Dairy farmers will need to think about their breeding choices to ensure they have a herd capable of producing milk with higher fat content to get the best returns, a new report says. DairyNZ strategy and investment leader Bruce Thorrold released the report, which said shifts in bull breeding worth (BW) reflected an increase in the value of fat.

Speaking after this week’s IFA National Dairy Committee meeting, Chairman Tom Phelan said representatives from all around the country were vocal and frustrated: dairy farmers’ backs are to the wall, and only higher milk prices – starting with 1c/l for August milk – will help with the massive expenditure increase on fodder and feed necessary to keep the milk flowing.

Speaking after this week’s IFA National Dairy Committee meeting, Chairman Tom Phelan said representatives from all around the country were vocal and frustrated: dairy farmers’ backs are to the wall, and only higher milk prices – starting with 1c/l for August milk – will help with the massive expenditure increase on fodder and feed necessary to keep the milk flowing.

The importance of proper care and management of dairy cows during the final 60 to 45 days of their pregnancy cannot be overstated. The nutrition, health care, and environment provided during this period have a tremendous influence on their health and performance well into the next lactation.

The importance of proper care and management of dairy cows during the final 60 to 45 days of their pregnancy cannot be overstated. The nutrition, health care, and environment provided during this period have a tremendous influence on their health and performance well into the next lactation.

When building a dairy parlour, there are a variety of different materials you can use for walls.

When building a dairy parlour, there are a variety of different materials you can use for walls. The concept of limit-feeding or precision feeding dairy heifers has been studied for the last decade primarily at Penn state and the University of Wisconsin. The goal of this research was to decrease costs while providing for adequate growth and performance after the heifer calves.

The concept of limit-feeding or precision feeding dairy heifers has been studied for the last decade primarily at Penn state and the University of Wisconsin. The goal of this research was to decrease costs while providing for adequate growth and performance after the heifer calves. Prevention of mastitis requires reducing exposure to mastitis pathogens and enhancing the ability of the heifers’ immune system to respond.

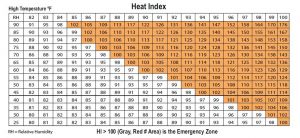

Prevention of mastitis requires reducing exposure to mastitis pathogens and enhancing the ability of the heifers’ immune system to respond. The unusually hot summer of 2018 has proved challenging for farmers across the UK. Among other things, the scorching weather and lack of rain has damaged crops, and the grass used to feed farm animals too.

The unusually hot summer of 2018 has proved challenging for farmers across the UK. Among other things, the scorching weather and lack of rain has damaged crops, and the grass used to feed farm animals too. Mental health can be defined as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to contribute to his or her community.” In contrast, a mental health disorder is a diagnosable illness that affects a person’s thinking, emotional state, and behavior and disrupts the person’s ability to work, carry out other daily activities, and engage in satisfying personal relationships. All of us exist somewhere on a spectrum ranging from good mental health to having a mental health disorder. Stress at work, financial problems, health issues, excessive drinking, and social or family problems can move someone from the healthy to unhealthy end of the spectrum.

Mental health can be defined as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to contribute to his or her community.” In contrast, a mental health disorder is a diagnosable illness that affects a person’s thinking, emotional state, and behavior and disrupts the person’s ability to work, carry out other daily activities, and engage in satisfying personal relationships. All of us exist somewhere on a spectrum ranging from good mental health to having a mental health disorder. Stress at work, financial problems, health issues, excessive drinking, and social or family problems can move someone from the healthy to unhealthy end of the spectrum. Hitting the outlined targets for harvesting corn intended for silage can offer dividends through exceptional feed over the next year.

Hitting the outlined targets for harvesting corn intended for silage can offer dividends through exceptional feed over the next year. The word ‘Immune’ has become a buzz word in the dairy industry over the past few years. You can feed this, or inject that, or breed for improved immunity…it can be very confusing to even know where to start! Let’s take a quick look at the very basic and critical role that omega fatty acids play in improving immune health.

The word ‘Immune’ has become a buzz word in the dairy industry over the past few years. You can feed this, or inject that, or breed for improved immunity…it can be very confusing to even know where to start! Let’s take a quick look at the very basic and critical role that omega fatty acids play in improving immune health.

Lyden Rasmussen, owner of Koro Dairy, hosted a successful grazing and pasture management field day on July 26, 2018, to teach other farmers about the benefits of Managed (Rotational) Grazing. Koro Dairy showcased their successful transition to a managed rotational grazing operation. Through the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s (NRCS) Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), the dairy was able to obtain a managed grazing plan, and a design and installation guideline for structural practices such as fences and watering facilities. EQIP provides financial assistance for a variety of practices intended to help farmers to achieve environmental goals on their land. With the Prescribed Grazing Practice, farmers receive a flat rate payment to implement a grazing system and commit their land to permanent pasture for 5 years. “This practice includes developing a prescribed grazing plan that considers the resources on the farm, such as soil productivity, landscape, livestock type, environmentally sensitive areas and water sources to determine carry capacity and stocking rates for pastures, paddock layout and hay harvesting schedules,” said Brian Pillsbury, State Grazing Specialist for NRCS in Madison. Other EQIP cost-shared practices that facilitate this practice are fencing, animal trails/walkways, forage planting, pipeline and watering facilities.

Lyden Rasmussen, owner of Koro Dairy, hosted a successful grazing and pasture management field day on July 26, 2018, to teach other farmers about the benefits of Managed (Rotational) Grazing. Koro Dairy showcased their successful transition to a managed rotational grazing operation. Through the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s (NRCS) Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), the dairy was able to obtain a managed grazing plan, and a design and installation guideline for structural practices such as fences and watering facilities. EQIP provides financial assistance for a variety of practices intended to help farmers to achieve environmental goals on their land. With the Prescribed Grazing Practice, farmers receive a flat rate payment to implement a grazing system and commit their land to permanent pasture for 5 years. “This practice includes developing a prescribed grazing plan that considers the resources on the farm, such as soil productivity, landscape, livestock type, environmentally sensitive areas and water sources to determine carry capacity and stocking rates for pastures, paddock layout and hay harvesting schedules,” said Brian Pillsbury, State Grazing Specialist for NRCS in Madison. Other EQIP cost-shared practices that facilitate this practice are fencing, animal trails/walkways, forage planting, pipeline and watering facilities. One of the most difficult things for farm managers/owners to master is coaching employees for optimal performance. Just like becoming an 85% free throw shooter on the basketball court, it takes practice. Once mastered you will see employees who understand goals and expectations more clearly, are more motivated, have ownership of their work, show greater responsibility, while maximizing their potential and problem solving ability. What you as an employer get is more productivity and lower turnover along with being freed of the day-to-day micromanagement of employees.

One of the most difficult things for farm managers/owners to master is coaching employees for optimal performance. Just like becoming an 85% free throw shooter on the basketball court, it takes practice. Once mastered you will see employees who understand goals and expectations more clearly, are more motivated, have ownership of their work, show greater responsibility, while maximizing their potential and problem solving ability. What you as an employer get is more productivity and lower turnover along with being freed of the day-to-day micromanagement of employees. The effects of heat stress can continue long after cooler weather has arrived — even for cows not in milk. In fact, research has shown that proper cooling in the dry period improved subsequent lactation by up to 16 pounds more milk per day and 20 pounds more 3.5-percent fat-corrected milk (FCM) per day.1

The effects of heat stress can continue long after cooler weather has arrived — even for cows not in milk. In fact, research has shown that proper cooling in the dry period improved subsequent lactation by up to 16 pounds more milk per day and 20 pounds more 3.5-percent fat-corrected milk (FCM) per day.1 When dairy cattle consume aflatoxin-contaminated feed, they are lethargic, their appetite wanes, they produce less milk, and their immune system goes awry. Some of those symptoms relate to oxidative stress, in which dangerous free-radicals bounce around, damaging cells. In a new study, researchers at the University of Illinois investigated the potential of injectable trace minerals to reduce the damage and keep dairy cows healthier.

When dairy cattle consume aflatoxin-contaminated feed, they are lethargic, their appetite wanes, they produce less milk, and their immune system goes awry. Some of those symptoms relate to oxidative stress, in which dangerous free-radicals bounce around, damaging cells. In a new study, researchers at the University of Illinois investigated the potential of injectable trace minerals to reduce the damage and keep dairy cows healthier. Modern dairy shelters provide the five freedoms of animal welfare that are essential to cow comfort and animal husbandry.

Modern dairy shelters provide the five freedoms of animal welfare that are essential to cow comfort and animal husbandry. Follow these tips for your automated alley scraper system

Follow these tips for your automated alley scraper system

“There’s a lot that can go wrong during the transition phase,” said Dr. Mark van der List, senior professional services veterinarian with Boehringer Ingelheim. “Their body undergoes many metabolic changes. It’s a high-risk period for dairy cows.” Diligent management techniques, proper nutrition and monitoring can help mitigate potential problems. Cows that undergo a successful transition may experience higher milk production, a reduction in post-calving disorders and improved reproductive performance.

“There’s a lot that can go wrong during the transition phase,” said Dr. Mark van der List, senior professional services veterinarian with Boehringer Ingelheim. “Their body undergoes many metabolic changes. It’s a high-risk period for dairy cows.” Diligent management techniques, proper nutrition and monitoring can help mitigate potential problems. Cows that undergo a successful transition may experience higher milk production, a reduction in post-calving disorders and improved reproductive performance.