- Drying off: When drying off a cow, the goal is to abruptly end milk secretion and to seal the teat canal as quickly as possible. Cows should not be milked intermittently towards the end of lactation because this prevents the teat canal from sealing and creates continued stimulus for milk production, increasing a cow’s risk for developing mastitis. After the cow’s final milking, the veterinarian-recommended dry cow therapy should be administered. Teat sealant may also be administered to prevent bacteria from entering the teat cistern and causing new infections. Finally, the entire surface of the teats should be covered using an effective teat dip.

- Dry cow therapy: The cow is very vulnerable to new infections during the first three weeks after drying off, so all quarters should be treated with a dry cow mastitis treatment. During this time, risk of infection is higher because physiological changes occur in the mammary gland, bacteria do not get flushed out of the streak canal during the milking process, there is no protection from teat-dip, and milk leakage occurs. Dry cow therapy can clear up an estimated 70 to 98% of already existing infections and helps prevent new infections, making it one of the most economically beneficial methods for mastitis prevention. The prevention of subclinical mastitis is especially important at this time because it can precede clinical cases and, depending on its causative pathogens, can infect other animals. A long-acting intra-mammary antibiotic should be administered to every quarter after the cow’s final milking.

- Nutrition of dry cows: Nutrition during the dry period is important for maintaining proper body condition score of 3.0 to 3.25. Separate diets should be made for far-off and close-up dry cows. Diets of far-off cows should contain less energy and adequate amounts of fiber. Diets of close-up cows should contain more metabolizable protein and energy than diets of far-off dry cows, but should still contain controlled amounts of both energy and fiber to ensure adequate feed intake after calving. Depletion of protein reserves during the dry period can negatively affect the cow’s health, milk production, and reproductive performance during the following lactation. Diets of close-up cows can also contain forages that are lower in potassium, such as corn silage, and grain products to help prevent milk fever after calving. If a herd is not big enough or it is not possible to manage close-up and far-off dry cows separately, dry cows can be managed as one group with a shorter dry period and a negative DCAD diet.

- Length of dry period: Dry periods typically last 60 days and involve both a far-off and a close-up period. The close-up period begins three weeks before expected calving. Research has found that if no dry period is provided for a cow, she will produce 25 to 30% less milk the next lactation. However, some producers have recently begun shifting to using shorter dry periods of 40 to 42 days. These shorter dry periods involve only one group and are paired with a negative dietary cation-anion difference (DCAD) nutrition program. Some argued benefits of using this program include having cows producing milk for 18 to 20 more days and less labor and stress involved since cows only have to be kept in one group rather than two. Research has found that there is no difference in milk yield following a 30-day dry period versus a 60-day dry period for multiparous cows. However, 30-day dry periods in primiparous (first-calf) cows have been found to result in reduced milk yield.

- Minimizing heat stress: Heat stress should also be prevented by providing proper cooling through the use of shade, fans, and sprinklers. Heat stress reduces the amount of mammary tissue that can be developed, so a cow that is heat-stressed during her dry period will have a reduced capacity for producing milk in her following lactation. Studies have shown dry cows that are cooled during summer months can produce 10 to 12 lb. more milk per day during lactation than cows that do not receive additional heat abatement.

- Minimizing social, environmental, and metabolic stress for close-up cows: Stress can affect feed intake, immune function, and overall health and productivity of cows around the time of calving. Social stress can be minimized by having as few pen moves or regroupings of cows as possible so that the social hierarchy of the cows is not disturbed. Adding multiple cows to a group at once is preferable to adding cows individually. Social and metabolic stress can be reduced by providing 36 inches of feed bunk space per cow to ensure adequate dry matter intake and reduce competition for feed. A minimum of 1 freestall or100 to 125square feetper cow should be provided to ensure adequate lying time.

Drying off cows abruptly, administering veterinarian-recommended dry cow therapy, and using a teat sealant will help protect cows from pathogens during the dry period and prevent mastitis in the following lactation. Meeting nutrition requirements of cows, depending on what phase of the dry period they are in and the length of the dry period, will help prevent transition cow disorders and ensure maximum milk production in the following lactation. Providing adequate heat abatement will prevent the negative effects of heat stress and minimizing regrouping and pen moves will minimize social stress of dry cows. Following these steps will help dry cows have better health, milk production, and reproductive performance in their next lactation.

Source: afs.ca.uky.edu

Sidedness in behavior – known scientifically as laterality – is commonly observed with dairy cows. Cattle express laterality naturally when choosing which side to lie down or which side of the milking parlor to enter. Over the years we’ve realized that this preference for one side over the other actually reflects cerebral specialization of the left and right hemispheres. For instance, the right hemisphere of the brain handles fear and anxiety (i.e., negative emotions); the left hemisphere processes positive emotions and longer-term memories.

Sidedness in behavior – known scientifically as laterality – is commonly observed with dairy cows. Cattle express laterality naturally when choosing which side to lie down or which side of the milking parlor to enter. Over the years we’ve realized that this preference for one side over the other actually reflects cerebral specialization of the left and right hemispheres. For instance, the right hemisphere of the brain handles fear and anxiety (i.e., negative emotions); the left hemisphere processes positive emotions and longer-term memories. Closely monitoring herd performance is vital to a successful dairy operation but is critical during economic downturns. Operations can achieve greater success by establishing advisory teams with their consultants. Milk production, somatic cell counts, pregnancy rate, culling rate, and income over feed cost are just a few of the metrics available for monitoring among dairy advisory teams. It does not take long to see the list of metrics to monitor and discuss grow and grow, especially for teams that have functioned for a few years or shifted gears. As the list of metrics to monitor grows, less time is spent with the team addressing current issues. Prioritizing the list of metrics to monitor can allow for appropriate time spent with both current issues as well as long term trends. Here are a few questions to consider when maximizing the time available to the advisory team while keeping key data and information involved with the process.

Closely monitoring herd performance is vital to a successful dairy operation but is critical during economic downturns. Operations can achieve greater success by establishing advisory teams with their consultants. Milk production, somatic cell counts, pregnancy rate, culling rate, and income over feed cost are just a few of the metrics available for monitoring among dairy advisory teams. It does not take long to see the list of metrics to monitor and discuss grow and grow, especially for teams that have functioned for a few years or shifted gears. As the list of metrics to monitor grows, less time is spent with the team addressing current issues. Prioritizing the list of metrics to monitor can allow for appropriate time spent with both current issues as well as long term trends. Here are a few questions to consider when maximizing the time available to the advisory team while keeping key data and information involved with the process. AIMING to drive production and breed the best cows they can, South Australian dairy farmers Graeme and Michele Hamilton and their son Craig, are focused on keeping good records to help them make informed decisions.

AIMING to drive production and breed the best cows they can, South Australian dairy farmers Graeme and Michele Hamilton and their son Craig, are focused on keeping good records to help them make informed decisions. The performance of dairy cows is mainly determined by genetic merit, but without proper management by knowledgeable and capable farm personnel, dairy cows will not be able to fully express their genetic potential. In order to properly manage dairy cows to allow them to excel, it is critical to establish a reliable team of farm personnel who are routinely trained using up-to- date and easy-to-understand training materials. Despite the unquestionable importance of personnel training in dairy farms, only 60% of the dairy operations in the U.S. provide such training (USDA, 2014). Of this 60%, 41% provide oral presentation trainings, while only 12% provide training using interactive teaching methods, such as educational videos (USDA, 2014).

The performance of dairy cows is mainly determined by genetic merit, but without proper management by knowledgeable and capable farm personnel, dairy cows will not be able to fully express their genetic potential. In order to properly manage dairy cows to allow them to excel, it is critical to establish a reliable team of farm personnel who are routinely trained using up-to- date and easy-to-understand training materials. Despite the unquestionable importance of personnel training in dairy farms, only 60% of the dairy operations in the U.S. provide such training (USDA, 2014). Of this 60%, 41% provide oral presentation trainings, while only 12% provide training using interactive teaching methods, such as educational videos (USDA, 2014).

When dairy producers have valuable genetic and management information but fail to take advantage of it, it might be termed unfortunate. However, think of all the potential information that could be provided but isn’t (yet); these absences are preventing real progress and can be called “missed opportunities.” Obviously, similar situations are pervasive everywhere in life, but fortunately U.S. dairy producers can avoid a few of these missed opportunities, which we’ll detail in this article.

When dairy producers have valuable genetic and management information but fail to take advantage of it, it might be termed unfortunate. However, think of all the potential information that could be provided but isn’t (yet); these absences are preventing real progress and can be called “missed opportunities.” Obviously, similar situations are pervasive everywhere in life, but fortunately U.S. dairy producers can avoid a few of these missed opportunities, which we’ll detail in this article. Silos full? With the recently-ensiled corn crop they should be as full as they are all year. Do you know what’s in each silo, and if so, is it written down? This is especially important if you grew both BMR and conventional corn for silage, or if some fields were affected by disease, drought or some other problem. It’s not good enough that you know where everything is, since unforeseen events (accident, sickness, etc.) could result in someone else needing to know what’s stored where. “If you don’t know where it is you don’t own it.” That’s not quite true with silage, but you get the idea.

Silos full? With the recently-ensiled corn crop they should be as full as they are all year. Do you know what’s in each silo, and if so, is it written down? This is especially important if you grew both BMR and conventional corn for silage, or if some fields were affected by disease, drought or some other problem. It’s not good enough that you know where everything is, since unforeseen events (accident, sickness, etc.) could result in someone else needing to know what’s stored where. “If you don’t know where it is you don’t own it.” That’s not quite true with silage, but you get the idea. Financial data from Midwest crop farms still looks better than you’d expect after more than five years of low grain prices, but lenders gathered at the National Agricultural Bankers Conference in Omaha, Nebraska, Sunday got seasoned advice on working with problem loans.

Financial data from Midwest crop farms still looks better than you’d expect after more than five years of low grain prices, but lenders gathered at the National Agricultural Bankers Conference in Omaha, Nebraska, Sunday got seasoned advice on working with problem loans. This is the third in a series of Dairy Financial Driver Profitability Quick Tips.

This is the third in a series of Dairy Financial Driver Profitability Quick Tips.

Is your farm struggling to meet the industry goal of 90 percent of calves with successful passive transfer? If you have enough first milking colostrum to allocate six quarts (1.5 gallons) to heifer calves, then you should consider a second colostrum feeding to your calves.

Is your farm struggling to meet the industry goal of 90 percent of calves with successful passive transfer? If you have enough first milking colostrum to allocate six quarts (1.5 gallons) to heifer calves, then you should consider a second colostrum feeding to your calves. Interest in the use of automatic milking systems (AMS) continues to be high, even in a stressed dairy economy. Some of the primary reasons reported for this change in milking technology include: 1) reduction in labor, especially hired labor, 2) more flexible life-style, and 3) potential improvement in cow heath and milk yield. At present (September 2018), we have about 2140 dairy farms in Ohio and 52 farms with AMS, with about 143 AMS on Ohio farms. Thus, about 2.4% of the dairy farms in Ohio have the AMS. The vendors are primarily Lely and DeLaval, with one farm now having installed the GEA system. Although the adoption rate in Ohio is growing, it is certainly less than in Europe, Canada (6.8% in 2015), and several other states in the US. One of the aspects of adopting the AMS system that can be challenging, at least for a few weeks, is the transition period from the conventional milking system to the AMS.

Interest in the use of automatic milking systems (AMS) continues to be high, even in a stressed dairy economy. Some of the primary reasons reported for this change in milking technology include: 1) reduction in labor, especially hired labor, 2) more flexible life-style, and 3) potential improvement in cow heath and milk yield. At present (September 2018), we have about 2140 dairy farms in Ohio and 52 farms with AMS, with about 143 AMS on Ohio farms. Thus, about 2.4% of the dairy farms in Ohio have the AMS. The vendors are primarily Lely and DeLaval, with one farm now having installed the GEA system. Although the adoption rate in Ohio is growing, it is certainly less than in Europe, Canada (6.8% in 2015), and several other states in the US. One of the aspects of adopting the AMS system that can be challenging, at least for a few weeks, is the transition period from the conventional milking system to the AMS.

Gippsland dairyfarmers Trevor Saunders and Anthea Day are committed to making rapid genetic gain in their 750-cow dairy herd, Araluen Park, and have the figures to prove their efforts are paying substantial dividends.

Gippsland dairyfarmers Trevor Saunders and Anthea Day are committed to making rapid genetic gain in their 750-cow dairy herd, Araluen Park, and have the figures to prove their efforts are paying substantial dividends. Typically, dairy farms have an opportunity after corn silage harvest to pump down lagoons and get manure hauled and applied. Hopefully, all goes well, without any accidents or manure spills, but hope is not a spill or accident prevention plan. Livestock operations that store, haul, and apply manure need to have an emergency response plan to handle manure spills and escapes. Preventing manure spills is one important component of that plan. A good start to preventing manure spills is to understand some common reasons manure spills occur, as well as where in the process from storage to application spills commonly occur.

Typically, dairy farms have an opportunity after corn silage harvest to pump down lagoons and get manure hauled and applied. Hopefully, all goes well, without any accidents or manure spills, but hope is not a spill or accident prevention plan. Livestock operations that store, haul, and apply manure need to have an emergency response plan to handle manure spills and escapes. Preventing manure spills is one important component of that plan. A good start to preventing manure spills is to understand some common reasons manure spills occur, as well as where in the process from storage to application spills commonly occur. Thank You for visiting 4dBarn in the World Dairy Expo 2018. It was our pleasure to participate show for the third time! We had a lot of good discussions about work efficiency and cow comfort in a robot barn.

Thank You for visiting 4dBarn in the World Dairy Expo 2018. It was our pleasure to participate show for the third time! We had a lot of good discussions about work efficiency and cow comfort in a robot barn. Increased soil moisture increases both the risk of runoff and manure movement to tile lines. Higher soil moistures lead to both slower infiltrations of applied manures and greater potential for leaching. Liquid manure applications will increase soil moisture further; for example, a manure application of 13,500 gallons per acre is equivalent to a half-inch rainstorm.

Increased soil moisture increases both the risk of runoff and manure movement to tile lines. Higher soil moistures lead to both slower infiltrations of applied manures and greater potential for leaching. Liquid manure applications will increase soil moisture further; for example, a manure application of 13,500 gallons per acre is equivalent to a half-inch rainstorm. Cows released from a Brandenburg farm have died after eating too much concentrate feed, according to local media. Dozens more remain in critical condition, spelling economic misfortune for a budding organic farm.

Cows released from a Brandenburg farm have died after eating too much concentrate feed, according to local media. Dozens more remain in critical condition, spelling economic misfortune for a budding organic farm.

The smell, the feeling, the NEW is always something we love to have or do, however it is not always possible or convenient.

The smell, the feeling, the NEW is always something we love to have or do, however it is not always possible or convenient. Frozen teats? Ouch. Elevated somatic cell counts and clinical mastitis? No, thank you. It’s time to prepare your milk quality program for winter.

Frozen teats? Ouch. Elevated somatic cell counts and clinical mastitis? No, thank you. It’s time to prepare your milk quality program for winter.

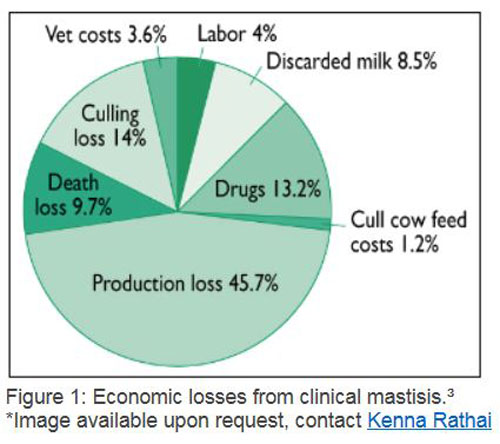

As feed, fuel, and fertilizer costs skyrocket, cost containment is front and center on everyone’s mind. It is important to note that improving income over expenses not just decreasing expenses should be your goal when looking for ways to improve or maintain profitability.

As feed, fuel, and fertilizer costs skyrocket, cost containment is front and center on everyone’s mind. It is important to note that improving income over expenses not just decreasing expenses should be your goal when looking for ways to improve or maintain profitability.

Handling, transportation, environment, feed, interactions with other animals, and interactions with humans can stress cattle. Do our attitudes influence factors that can affect profitability?

Handling, transportation, environment, feed, interactions with other animals, and interactions with humans can stress cattle. Do our attitudes influence factors that can affect profitability? Increasing labor productivity enables an industry or economy to produce the same amount or more output with fewer workers. Because labor productivity is directly related to output, it has a major impact on economic growth and the standard of living. U.S. labor productivity growth since 2011, at an annual rate 0.4 percent, is lower than the annual growth rate of 2.5 percent year experienced from 1995 to 2010 (Wolla, 2017). Unless this growth rate of labor productivity increases, slow economic growth rates and relatively low wage rate increases are likely.

Increasing labor productivity enables an industry or economy to produce the same amount or more output with fewer workers. Because labor productivity is directly related to output, it has a major impact on economic growth and the standard of living. U.S. labor productivity growth since 2011, at an annual rate 0.4 percent, is lower than the annual growth rate of 2.5 percent year experienced from 1995 to 2010 (Wolla, 2017). Unless this growth rate of labor productivity increases, slow economic growth rates and relatively low wage rate increases are likely. Unacceptably high calf mortality rates on Australian dairies cause significant financial loss to individual enterprises. The extent of this financial loss is often not appreciated because it is hard to assess.

Unacceptably high calf mortality rates on Australian dairies cause significant financial loss to individual enterprises. The extent of this financial loss is often not appreciated because it is hard to assess. Dairy farmers will need to think about their breeding choices to ensure they have a herd capable of producing milk with higher fat content to get the best returns, a new report says. DairyNZ strategy and investment leader Bruce Thorrold released the report, which said shifts in bull breeding worth (BW) reflected an increase in the value of fat.

Dairy farmers will need to think about their breeding choices to ensure they have a herd capable of producing milk with higher fat content to get the best returns, a new report says. DairyNZ strategy and investment leader Bruce Thorrold released the report, which said shifts in bull breeding worth (BW) reflected an increase in the value of fat.