Barn doors locked from the inside. Semen straws filled with dishwater. A $7,500 cow insured for $250,000—and two dairymen dead by their own hands within a week.

From 1920 to 1993, seven fraud cases ripped through the Holstein world, and the criminals weren’t strangers. They were buyers who talked bloodlines, vets who shipped bulls to slaughter, employees loading tanks after midnight, and young men chasing banners they couldn’t afford. Every scheme exploited the same flaw: an industry built on trust, light on verification, and slow to ask uncomfortable questions. Those weak spots haven’t gone anywhere. Here’s their playbook—and how to make sure it never works on your farm.

Act I – The First Siren

On a cold February morning in 1981, a neighbour in Barrie, Ontario, started blinking his headlights at the Cadillac coming toward him.

“Look behind you,” he told the driver. “There’s a fire over there. Looks like it might be your barn.”

Gordon Atkinson, one of the biggest cow buyers in the Holstein game, turned his car around. When he crested the rise, the smell hit before the sight—burning flesh, heavy smoke, and that sickening, sweet edge you don’t forget. The flames were already high, licking through the roof of the rented barn. Cattle were bawling. Neighbours stood helpless in the snow, hands jammed in pockets. They’d tried the doors. The doors were locked from the inside.

Atkinson didn’t get out of the car. He sat in the Cadillac and watched while sixty head, including the sons of a cow he’d paid $66,000 for, died in the fire. Those calves had been insured for $50,000 apiece. Think about that for a second—fifty thousand dollars a head on baby bulls that had barely hit the shavings.

That’s not a story about one bad fire. That’s the first siren.

Because once you start digging through the court files and breed journals, you see a pattern. Not just one crook or one crazy case, but a whole run of them: the smooth-talking buyer with the fake cheques, the vet who sold mail‑order bulls straight to the butcher, the semen dealer who turned dishwater into “Telstar,” the deadstock men who pushed tainted meat into family kitchens, the show guys who insured cows for a quarter million and then buried them, the barn doors locked from the inside.

The common thread isn’t just greed. It’s pressure and paperwork. It’s trust and timing. It’s the places where our industry runs on handshakes and assumptions, and how fast things go sideways when someone decides to weaponize that trust.

These aren’t ghost stories from some other world. Every one of them happened on farms, in sale rings, in co-op territories, and small-town courtrooms that look a lot like yours. And if there’s one thing these cases teach, it’s simple: the same weak spots those guys exploited are still with us.

So let’s walk through seven true cases—not to gawk at the wrecks, but to see where the bolts came loose.

Act II – The Pattern Under the Manure

We’ll follow the money first. Then the power games. Then the rules and the product—the stuff that goes in the tank and on the table. The stakes climb as we go.

1. Money & Paper: When the Stranger at the Lane Knows Your Cows Better Than You Do

Leroy Austin – The Saturday Afternoon Cheque

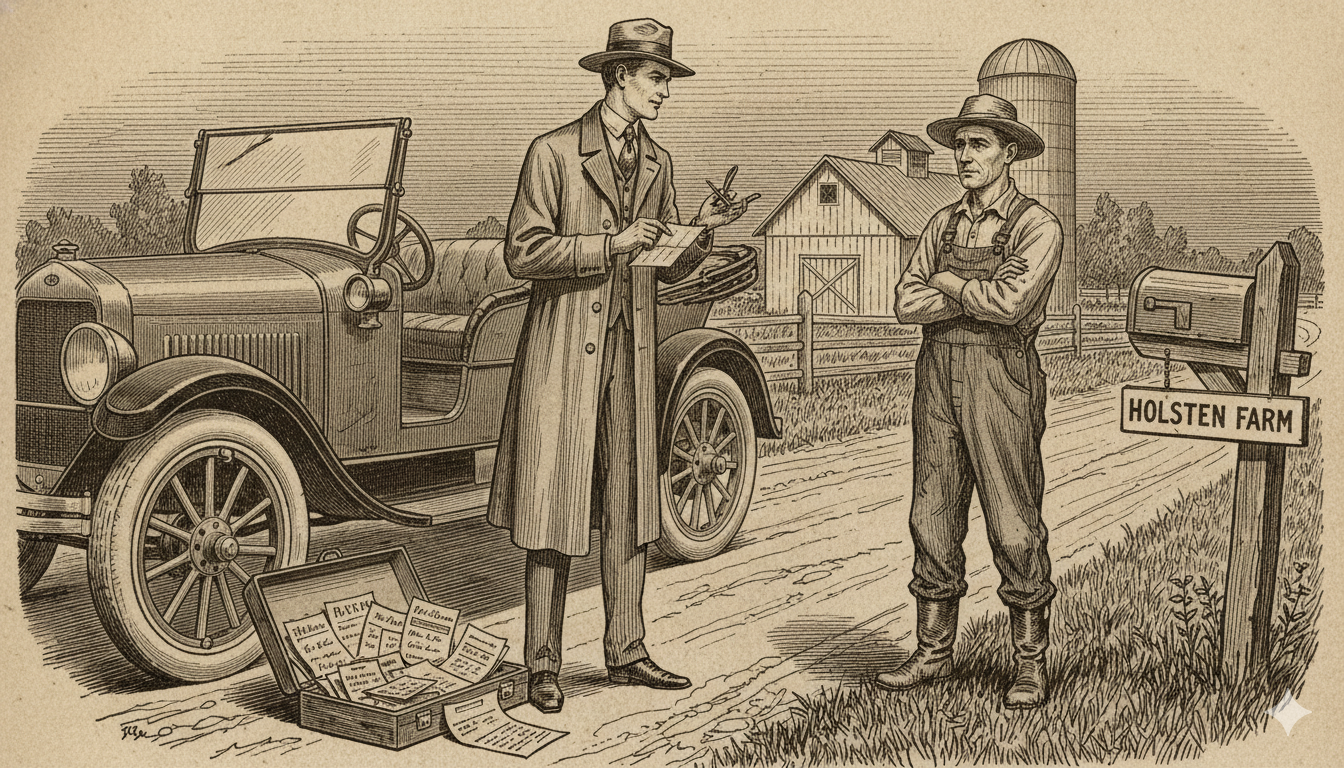

In the early 1920s, a tall, polite man with a southern accent began appearing in Michigan, Iowa, Illinois, and beyond. He knew cattle—really knew cattle. He’d walk your pens slowly, talk pedigrees, ask about your sires, and pick out the kind of Holsteins you’d be proud to sell.

He called himself H.C. Helms. Or sometimes L.C. Lingle. Or L.H. Cox. Or B.L. Baxton. The name didn’t matter. What mattered was the pattern. He always came late in the week, often late on a Saturday afternoon—just close enough to bank hours to make you feel rushed.

Here’s how it worked. He’d make the deal fair—maybe even generous. Then he’d say something like, “My bank’s out of state, but I’ve got this draft. If you just endorse it, we’re good.” He’d pull out telegrams from “banks,” passbooks, bank drafts, enough paper to look solid. One time, he cashed a cheque on his “aunt” in a town called Kalla, Michigan—a place that didn’t exist.

The cheques were always worthless. Under the law, the endorsers—farmers who thought they were just helping a good fellow move money—had to make good.

For months, he worked his way around the Midwest and into the South. The farm press finally sounded the alarm when J.C. Hays, secretary of the Michigan Holstein Association, wrote a letter to Holstein‑Friesian World naming him as Leroy Austin, born in Marshville, North Carolina, and listing his aliases. But it still took time before someone caught up with him in Waterloo, Iowa, and sent him to the Iowa State Penitentiary for seven years.

The Michigan dairymen he’d burned didn’t forget. When he finished his sentence, they were waiting at the gate, the sheriff in tow. They put the cuffs on and took him straight back to Michigan to face more charges.

Red flags you can see a mile away now:

- Big deals on a Saturday afternoon, right before banks close.

- A buyer who knows cattle cold but pushes you to endorse his paper.

- Credentials that look impressive but nobody’s actually called on.

On any modern farm, this is exactly where a second set of eyes stops the whole scam cold: “Sit tight. We’ll run this by the bank on Monday before we move a single cow.”

Dr. Morley Pettit – The Mail-Order Bulls That Never Got Home

Fast‑forward a decade. Southern Ontario’s tobacco belt. A veterinary surgeon named Dr. Morley Pettit has what looks like a respectable practice. Underneath, things are unraveling. Whether it was mental health, Depression economics, or just character, the record doesn’t say for sure—but the behaviour is clear.

First, it’s a tractor. He buys one for $963, hides it in the woods, repaints it when he can’t pay, and gets nailed for theft and fraudulent concealment—$100 fine, two years’ probation, told to support his family “in a proper Christian manner.”

Then he finds a better angle. In an era when purebred young bulls are shipped by mail order, he writes to breeders all over, presenting himself as exactly the kind of customer you want: a progressive dairy, stock, and tobacco farmer with grade cattle “equal in production to purebreds,” valuable tobacco land and kilns, and a $3,000 farm improvement program underway. It sounds solid. It sounds like growth.

The breeders ship the bulls on approval. The railway agent in Simcoe knew the drill by now: a crate marked “livestock” would arrive, Dr. Pettit’s name on the bill of lading. By the time the agent called to confirm delivery, the bull was already hanging in a butcher’s cooler twenty miles away. Pettit never gave those animals a chance to step onto his place properly. According to evidence later, he’d already lined up the butchers before the cattle left their home farms. The animals went from railway car to slaughter under cover of darkness, sold at “ridiculously low prices.”

He pays with promissory notes or promises of notes and then disappears behind “devious excuses and representations,” as the Crown Attorney put it.

One breeder testified that he’d shipped purebred livestock on trust for twenty years—cash, credit, didn’t matter—and Pettit was the first and only man who took advantage of him. That tells you a lot about the culture of that era. It also shows how much damage one determined fraudster can cause within a trust-based system.

Eventually, the civil courts are full of his name: 51 judgments in Windham, Delhi, and Simcoe, totaling $13,137.51—a small fortune at the time. When the criminal charges finally stick, Judge T.W. Godfrey gives him five years in Portsmouth Penitentiary.

In passing sentence, the judge spells out the heart of this kind of crime: Pettit played on the good name of his family in a community where “the name ‘Pettit’ was good in Norfolk.” That’s not just paperwork fraud—that’s weaponized reputation.

The lesson for now:

Any time cattle—or semen, or embryos—are moving without clear, verified payment arrangements, and the whole deal rests on “he seems like a good guy” or “the name rings a bell,” that’s your cue to slow down. Good reputations are valuable, but they’re not collateral.

2. Product & Brand: When the Tank and the Table Get Dirty

Now we pivot from money on paper to what actually moves through the system—semen, meat, milk. This is where fraud stops being just a balance-sheet problem and becomes a food safety and brand problem.

Jack Miller – Dishwater in a Telstar Straw

By the early 1970s, artificial insemination was the backbone of Holstein genetics. If the name “Roybrook Telstar” was printed on the ampule, most breeders took it as gospel that Telstar’s genes were in that straw.

Enter Jack C. Miller. Born and raised in Collegeville, Pennsylvania, he’d earned a master’s degree in pharmacology and worked as a pharmacist before switching careers after the war. He became a distributor for Curtiss Breeding Service, then eventually struck out on his own, importing Canadian Holstein semen.

He showed up at United Breeders in Guelph, Ontario, “just for a visit” at first—wanted to see the bulls. On later trips, he sought out the sire analyst, Lowell Lindsay. Lindsay noticed something: Miller knew everything about the hot bulls—Telstar, Citation R, the big names—but was fuzzy on the rank‑and‑file sires.

On subsequent visits, Miller drifted deeper into the back end of the operation. He introduced himself to Wouter Manten, the distribution manager, lingered in the loading area, and spent a lot of time with John Purvis, the lab manager, and Albert Ball, the truck driver. Before long, unbeknownst to United, Purvis and Ball were loading Miller’s van with tanks full of semen after hours.

A favourite transfer site? The Presbyterian Church parking lot on Highway 6 South, right by the 401 cutoff. If you haul in that part of Ontario, you can picture the scene in the dark—a church lot, two trucks, lids banging, nitrogen vapour spilling.

United’s manager, Wilbur Shantz, sensed something was off. Instead of making accusations he couldn’t prove, he started sleeping in his office. One night, he heard movement, saw Miller and Ball loading a truck after hours, and called the police.

The real horror showed up later in Indiana. Dr. G.W. Snider and his wife bought 2,000 ampules of Pickland Citation R semen from Miller at $3 a straw when the going rate was $7. “My suspicions were aroused,” Snider told investigators. He called the bull’s owner and United’s sales manager. Both said the same thing: that semen didn’t come from them.

When U.S. and Canadian authorities tore into Miller’s operation, they found his trick: he emptied discarded or cheap straws, re‑printed them with high‑value bull names, and refilled them with junk—sometimes fluid that looked like “dishwater,” sometimes raw milk, sometimes semen from the wrong breed. In one case, a straw labeled Nugget produced an Angus calf.

In the U.S., Miller pled guilty to smuggling and got 90 days in jail, a $10,000 fine, and five years’ probation. In Canada, he and Purvis pled guilty to defrauding ten breeders and United of $222,655 by selling fraudulent semen; Miller got 33 months after making restitution of 81 cents on the dollar. On conspiracy charges, they pulled another 18 months.

The fallout was brutal but necessary. The Health of Animals Branch quarantined tanks across the country and brought in Dr. J.W. MacPherson at the Ontario Agricultural College to test the contents. By the time he was done, material breeders had paid more than $500,000 for what had been destroyed.

And one small forensic detail cracked the case: Sgt. John Ogilvie of the OPP noticed that the ink on Miller’s fake Telstar ampules didn’t match the authentic ones. Each stud used a different ink colour, and Miller’s re‑printed straws still had specks of the old ink underneath.

After Miller, nobody in the A.I. world ever looked at a straw label quite the same way. At the 1974 World Premiere Sale in Madison, two vials of Telstar semen brought $2,000 each, but the catalogue spelled out the chain of custody—collected in 1966, shipped directly from United to Illinois Breeders in 1969—because by then everyone knew that Telstar ampules dated July 15, 1966, were fakes.

If you move genetics today:

- Be suspicious of “too good to be true” prices on hot bulls, especially when the seller arrives in a flashy car—Miller drove a Mercedes, and people remembered.

- Treat the chain of custody like gold. Who collected it? Who shipped it? Who stored it? If you can’t answer that straight, don’t put it in a cow.

- Remember: the fraud didn’t start in the lab; it started with relationships in the loading bay. Your weakest link might not be the paperwork—it might be the culture around it.

The Brantford Tainted Meat Scandal – Deadstock, Downers, and the Basket Stamp

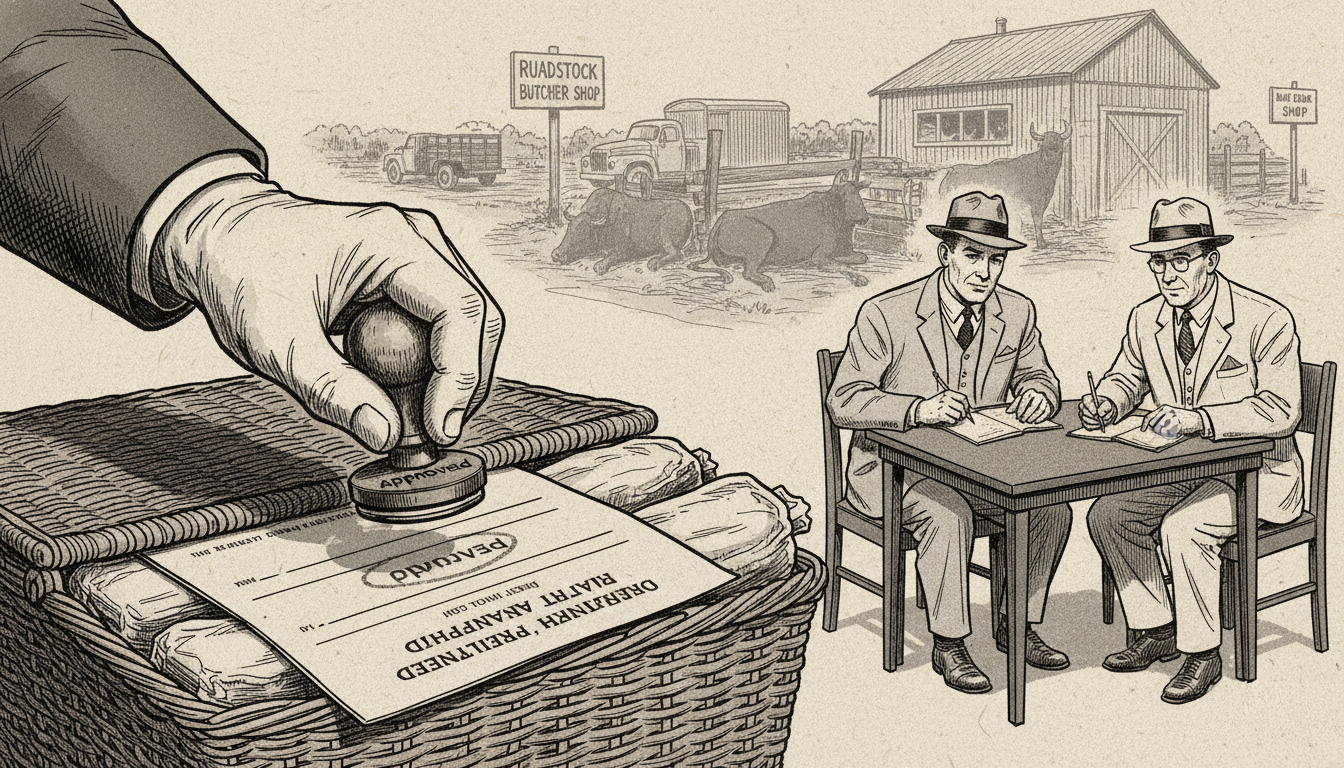

If Miller’s story shook confidence in what went into semen tanks, the Brantford tainted meat scandal of 1961 did the same for the meat counter.

Deadstock dealers—“dead animal disposal” licensees—were supposed to pull hides, cut carcasses, and sell meat as dog food or to zoos and pig farms, where it would be cooked. But if you could convince a Health of Animals inspector or local meat inspector to stamp your product as fit for human consumption, that same meat could move into grocery stores.

Some of this came down to loopholes. In Brant County, a county-employed meat inspector’s stamp was enough; you didn’t need a federal stamp. The law said no one could slaughter without an ante-mortem inspection, but as one case showed, the inspector might not even see the carcass.

The scandal broke when the Canadian Renderers’ Association noticed they were suddenly getting fewer deadstock carcasses; something wasn’t adding up. They complained. The Health of Animals Department called in the RCMP.

Two Mounties—Corporal Edward Drayton and Corporal Orville “Dusty” Lutes—went undercover as meat dealers “Eddy Jackson” and “Dusty.” They visited butcher Robert Hooton in Scotland, Ontario. He told them he had two tons of meat in freezers at Woodstock and Aylmer, all stamped by the Brant County Health Unit. He admitted he mixed deadstock meat with “downer” cattle—sick or disabled animals unable to stand—calling it “putting in a cheater.” He was buying for 25–26 cents a pound and selling at 36.

When they pressed him about getting meat stamped, he said it “would be no difficulty.”

They then visited deadstock dealer Allan Carey, one of four big brothers in the trade, under the name Walnut Ranch. Carey, too, was willing to move “cheap meat” their way.

At the heart of the storm stood Dr. Ormond C. Raymond, head of the Brant County Health Unit. In court later, he testified that he’d given the officers some stamped papers—“Department of Health, Brantford, Approved”—for $25, then thought better of it, returned the money, and refused further deals. He admitted stamping a basket of meat at Hooton’s, but said he’d inspected it and believed it fit for human consumption.

The press went wild. The Brantford Expositor’s front page shouted, “CHARGE FOUR SOLD UNFIT MEAT HERE.” The scandal even hit Time and Newsweek.

In court, Justice Reville picked apart the Crown’s conspiracy case against Dr. Raymond, noting that if there truly had been an agreement to stamp deadstock as wholesome meat, there’d be no reason for co‑accused Charlie Thomson to lie to Raymond about whether the meat was fresh. He acquitted Raymond but convicted Carey and Hooton.

For farmers, the lesson isn’t in the legal hair‑splitting; it’s in the setup. The whole racket depended on three weak points:

- A shortage noticed by downstream users—renderers missing carcasses, not regulators crunching numbers.

- Inspectors who were treated as rubber stamps instead of guardians. One butcher said, “The Doc did not see the meat, just stamped the paper,” according to testimony.

- A culture where people assumed “somebody” was watching the gate.

Today, slaughter is much tighter: centralized plants, inspectors at the rail, traceability built into the system. But the pattern is the same one Miller used: take something of low value, pass it through a trusted seal, and sell it as high-grade. Whether it’s meat, semen, or milk tests, the label is only as strong as the process—and the people—behind it. The same principle applies to bulk tank tests, component samples, or any piece of paper that determines what you get paid—the stamp is only as honest as the system behind it.

3. People & Power: When Reputation Runs Ahead of Character

Some crimes don’t start with paperwork or product. They start with people everyone already knows.

Duncan Spang – The Cattle Man with the Hot Cheques

If you showed up at Holstein shows in Ontario from the 1930s to the 1960s, you probably knew the name Duncan “Dunc” Spang. He grew up on a farm near Claremont, Ontario, fell in love with Holsteins early, and made a career trading cattle. He had an “eye for a cow” that top herds like Oak Ridges relied on—he’d spot the gems in the back concessions and tip off buyers who wouldn’t take his cheques but would gladly buy where he pointed.

He also had a long, messy relationship with rules.

As a young man, he got involved with a used-car dealer named John White and a crooked bank manager. White would jot down car registration numbers at his station, then file bogus loan applications with Spang’s name as borrower, using cars he’d never seen as collateral. When the RCMP pulled the string, White and the bank manager went to jail, and Spang received a suspended sentence for fraud.

Later, the Holstein Association expelled him for misrepresenting parentage and other misdemeanours, effectively blackballing him from the purebred business. He adapted by collecting signed transfer blanks and registration papers, keeping them stacked in the back seat, inserting buyers’ names later.

Money was always tight. Neighbours knew that taking a Spang cheque was risky. One magistrate heard a case in which Spang was convicted of passing a bad cheque for cattle and fined $250 plus costs. Spang looked up at the bench and said, “Would you take a cheque for that, Your Honour?”

Yet when Duncan Spang died in 1983—after being shot in the stomach by intruders who broke into his farmhouse and left him to drive, intestines hanging out, to his brother’s butcher shop for help—the community mourned. Even farmers who’d been burned by his cheques talked about his talent, his quirks, and the cows he’d steered them toward.

This is the uncomfortable part of crime stories: some of the people who bend the rules are also the people who spot the great cows, haul your animals, or share a coffee at the show. It’s not a cartoon of “good” and “evil.” It’s messy, human, and that’s exactly why it’s so dangerous.

Practical takeaway: being good with cattle or good company at a show ring doesn’t make someone a safe business partner. Split those categories in your head. Trust a man’s eye for a cow if he’s earned it; verify his cheques as if you’d never met.

4. Rules, Records & Regulators: When the System Itself Gets Bent

If Duncan Spang showed how a colourful character can dance on the edge of the rules, Gordon Atkinson shows what happens when big names and big valuations meet big insurance.

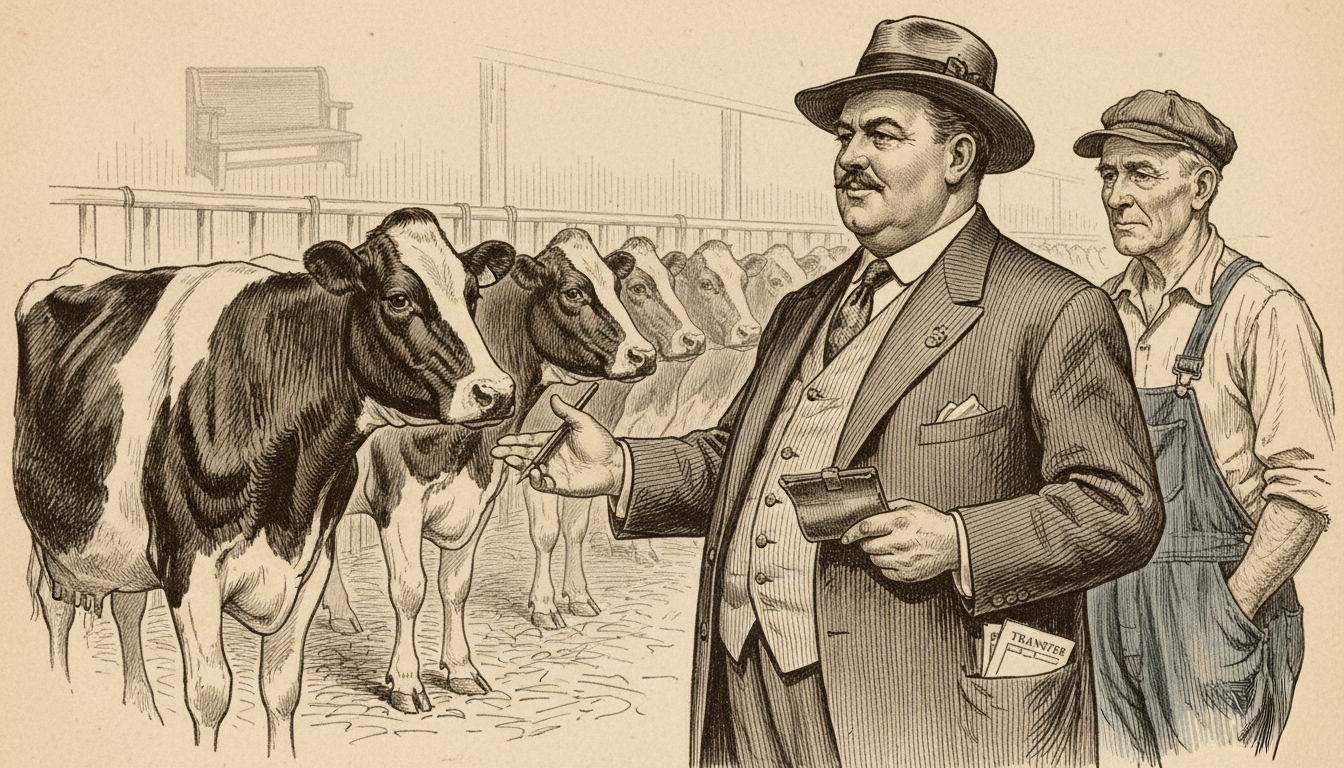

Gordon Atkinson – Black Days at Meadolake

In the 1960s and ’70s, Gordon Atkinson was everywhere that big Holstein money moved. At the Brubacher 300 Sale in 1968, he bought Seiling Perseus Anna for $37,500. At Orton Eby’s dispersal two years later, he paid $40,000 for her daughter Heritage Rockanne—a record price for a bred heifer—outbidding Steve Roman to do it. On the same day, he added Brubacher Supreme Penny for $23,000 and her dam, Seiling Adjuster Pet, for $15,500.

He bought more at Fred Lingwood’s dispersal—Llewxam Nettie Piebe A for $50,000—and then took his biggest swing at the Romandale dispersal in 1979: Romandale Telstar Brenda for $66,000, after her son Romandale Pride had sold to Japan for a world‑record $400,000. Fifteen Citation R sons out of Brenda followed at Meadolake. “That’s a lot of bulls but I’m not worried,” Gordon told a friend. “They’re three‑quarter brothers to the $400,000 bull… And besides, they’re insured.”

That line hits different once you know what came next.

We’ve already walked through the first fire: locked doors, sixty head dead, heavily insured calves, Gordon in the Cadillac. There was a second barn fire two years later—more cattle gone. Seiling Perseus Anna went to a flush program, fell, split herself, and had to be destroyed; she was heavily insured, sparking rumours.

Then came Farlows Valiant Rosie. All‑American 4‑year‑old in 1984, she looked poised to be the “hotshot” of the 1985 show season. She topped her class at the Ontario Spring Show, but at the Royal, she didn’t even make the ring. She’d slipped from potential All‑Canadian to Honourable Mention, and then she went downhill. In the fall of 1985, she was found dead.

This is where the story stops being barn gossip and turns into a criminal file.

Gordon’s son John, who worked with him, later told investigators that his father had given him specific instructions on how to kill insured cows, according to court records. “Use Succinylcholine,” Gordon allegedly said. “Inject it under her tail.” It’s the same drug that would later show up in the Wilcom and Wright case—fast‑acting, hard to trace.

When Gordon asked John to sign an insurance form for Rosie, John refused. He knew what had happened; he wasn’t going to lie on paper. That was the line he couldn’t cross.

Not long after, Gordon was charged with defrauding insurance companies out of roughly $12 million in livestock claims, according to Crown filings, including calves insured at $50,000 each. The Crown alleged a pattern: heavily insured animals dying under suspicious circumstances, inflated valuations, overlapping policies.

Family life imploded. At one point, according to a family friend, Gordon told his wife that if she testified against him, he’d poison their grandchildren. She and the kids left.

When the legal dust settled, Gordon cut a plea deal. He pled guilty to some charges, avoided a long prison term, but lost almost everything. The bank took the farm. The big-name cows were scattered through dispersals and private sales. Some neighbours still remembered him as “the best neighbour I ever had.” Others called him “absolutely evil.” Both versions show up in the record.

The hard truth for every farm reading this: the weakness here wasn’t just in Gordon’s character. It was in how easily a charismatic, hard‑driving breeder could stack insurance, inflate values, and file claims without enough independent scrutiny. The cows were famous. The records weren’t questioned soon enough.

Wilcom & Wright – Succinylcholine, Three Dead Cows, Two Dead Men

If Atkinson’s story is about what happens when an older operator pushes luck and leverage too far, the Wilcom and Wright case is about how quickly a young show career can go off the rails when insurance money and status get tangled.

In March 1993, 26‑year‑old dairyman Greg Wilcom sat on the couch next to his wife Pamela, holding her hand. “Cows will come and go,” he told her. “But you and I are forever. Through good times and bad, I love you.” He asked for two things: that his Premier Exhibitor banner from Madison be placed in his coffin, and—before he could voice the second request, he died. A Baltimore coroner ruled it a suicide by strychnine.

Five days later, his sometime business partner, Jim Wright, rented a motel room and shot himself in the chest.

The Frederick County Sheriff’s Department and private investigator William Graham suspected the obvious connection: an insurance scam on three “top‑drawer” Holstein cows. The men had claimed about $330,000 total from various companies.

One of the cows, Fran‑Lou Valiant Splendor, was bought for $7,500, then insured for a quarter of a million dollars. She had a spectacular pedigree—out of Dreamstreet Sexation Sherri and descending from the famous Poverty‑Hollow Shirley family—but as an individual, she wasn’t exceptional. That combination—ordinary cow, extraordinary paper—was one of the first red flags other dairymen pointed to later.

When Graham drove from South Carolina to Preble, New York, to interview Wright, he found a confident, helpful cattleman. Wright said Splendor had been eating well at dawn and was dead two hours later, apparently suffocated in a bunk feeder. His vet, Dr. Joseph Wilder, supported that explanation. Wright patiently explained the show-cow economics and came across as “squeaky clean.”

But the numbers bothered Graham. How does a $7,500 cow jump to a $250,000 claim that fast? And why had two other high‑profile cows Wilcom sold Wright also died soon after arriving at Wright’s farm? Add to that: two previous suspicious barn fires on Wright’s property and the fact that the three dead cows were each insured with different companies.

Then came the tip that tied this story to Atkinson’s world. Former Hanover Hill herdsman turned hauler Willis Conard told Graham he suspected Wilcom and Wright were using succinylcholine, injected into a tail vein, to drop cows instantly. It’s a muscle relaxant used in human medicine, notorious in murder cases because it leaves the body quickly and can be hard to detect.

Graham phoned Wilcom. “Greg, I’ve got a problem,” he said. “I need full financial disclosure. Everything. And I want a statement under oath.”

“What’s the problem?” Wilcom asked. “The problem with the tail veins and the succinylcholine.”

Silence. Then a click. Wilcom hung up.

Within days, both men were dead. Whatever drove them to that point, two families lost husbands and fathers. Investigators never fully untangled the motive. Some floated theories about organized crime, Colombian drug connections, and FBI surveillance at the Royal. Others thought it was simply a case of two young men in over their heads, facing exposure they couldn’t stomach. Norman Nabholz put it bluntly: showing cows can be an addiction, and Greg “didn’t have the money to support his addiction.”

The insurance company eventually settled Splendor’s claim for $7,500—the original purchase price.

What makes this story so unsettling is that the people involved weren’t fringe players. Wilcom had owned or held interests in cows like Aitkenbrae Starbuck Ada, Cathland Lilac, Hanson Prestar Monalisa, and Rossland Astro Kat—cows that lit up Madison and the Gay Ridge and Kingstead sales. Wright had judged shows around the world.

The weak spot wasn’t that strangers had slipped into the industry. It was that the industry had no built‑in way to handle the jump from reasonable values to quarter-million-dollar policies on cows whose main asset was their pedigrees. No automatic “this doesn’t smell right” review. No hard rule that says: if you’ve had multiple high‑value losses in a short span, somebody outside your circle is going to walk your records and your barn.

This is where your own playbook has to be clear:

- Don’t insure cattle for numbers you’d be embarrassed to defend to a roomful of fellow breeders. If you can’t explain the valuation out loud, it’s probably a bad idea.

- If you have multiple big losses close together—fires, sudden deaths—that’s the moment to invite an outside advisor in before the adjuster shows up. Let someone you trust help you tighten up and, if needed, draw a hard line you won’t cross.

- And if you’re that advisor—the vet, the banker, the co‑owner—you have to be willing to ask the questions nobody wants to hear. That’s what Graham did. It didn’t save Wilcom and Wright, but it likely stopped the pattern from spreading.

Act III – After the Headlines

The headlines in all these cases were big: fraud, smuggling, conspiracy, tainted meat, dead cows, dead men. But the real story—the one that matters to you—is what happened after the reporters went home.

When Miller got hauled off, half a million dollars’ worth of bogus semen was destroyed, and the A.I. industry learned the hard way that “we’ve always trusted the label” isn’t a control system. It forced proper chains of custody, ink‑colour checks, tighter lab protocols, and a healthier level of suspicion when a deal looked too sweet.

When the Brantford meat scandal blew up, the old farmer‑butchers and small back‑barn kill floors faded. Bigger, inspected plants took over, and inspectors started standing at the rail instead of signing baskets in backrooms. That didn’t just protect consumers; it protected honest butchers and farmers whose livelihoods depended on trust in the food system.

When Atkinson finally hit the wall, neighbours saw what happens when a farm runs on borrowed money, stacked policies, and “don’t ask too many questions.” The cows went, the farm went, the family scattered. But his son John, who refused to sign a false claim and faced down credible threats, showed that one person saying “no” at the right moment can stop a bad situation from becoming something even uglier.

When Wilcom and Wright died, the Holstein world talked quietly at ringsides and barn alleys. Nobody had a neat answer. But a lot of folks quietly toughened their own standards on valuations, partnerships, and how far they’d go to keep a banner coming.

Underneath all that drama, there’s a simple prevention playbook. Not a list your insurance company sends you, but something you can actually picture on your own farm.

The Bottom Line

Let’s bring this right back to your yard.

Picture a plain kitchen table. Coffee mug rings, calf jackets hanging on the chair backs, milk statement laid out next to a notebook and a pencil. Outside, the night lights over the yard cast that familiar glow on the parlour roof. You’re tired. The day’s been long. But you sit down anyway and start running your finger down the line items.

The milk check jumped 15% this month. Did your herd size jump 15%? Did your components improve? Did your ration cost drop? If nothing in the barn changed, but the paper did, that’s not just a nice surprise. That’s a question.

The semen invoice shows a hot bull at half the going rate from a guy who just rolled in with a shiny truck and a big story. That’s not “lucky.” That’s another question.

A buyer wants you to endorse his bank draft “just to speed things up,” and it’s late Friday. You know better now. You’ve heard Austin’s story. You can almost see the handcuffs at the prison gate. The right move isn’t heroic; it’s boring. “Let’s wait until Monday. We’ll talk to the bank.”

Your partner—or even a family member—wants you to sign a blank claim form “so we can get this sent in.” You remember John Atkinson looking at that paper and deciding that, for him, the line was his signature. You can feel how heavy that pen must’ve been.

Most of the time, nothing dramatic is happening on your farm. That’s a good thing. But the habits you build in the quiet seasons are what save you when things get tight:

- Two sets of eyes on big cheques, big loans, and big insurance policies.

- Clear, boring, written agreements with partners and co‑owners.

- A culture where the hired man or the bookkeeper feels safe saying, “This doesn’t look right.”

- The willingness to pick up the phone and verify—even if it makes you feel awkward.

And if you see something that doesn’t add up on someone else’s operation? You’re not being a busybody—you’re protecting the industry’s reputation. A quiet call to your co-op manager or breed association costs nothing and could save everyone.

One more picture to leave you with.

It’s late. The parlour’s washed. The fans are humming. You’re at that kitchen table with your coffee and the milk statement. Your son or daughter—maybe they’re taking more responsibility now, maybe they’re coming back from college, maybe they’ve just bought into the herd—pulls up a chair.

They don’t ask for the tractor’s keys. They don’t ask for the show string. They ask for their own copy of the statement.

That’s the farm that doesn’t end up as a cautionary tale at a co‑op meeting. That’s the operation where trust still means something because it’s backed up, every month, by someone actually reading the numbers, asking the hard questions, and deciding ahead of time where the line is.

Today’s cons have new delivery systems—wire transfers instead of Saturday cheques, spoofed emails instead of forged passbooks—but the playbook is the same: exploit trust, move fast, count on you not to verify.

Cows will come and go. Prices will rise and crash. There will always be someone looking for a soft spot in the system. But integrity isn’t a slogan you hang in the office—it’s a practice. It’s the quiet, stubborn decision that on your farm, the barn doors stay open, the records match the reality in the yard, and no cheque, no straw, no policy is ever worth more than your name.

Key Takeaways

- The danger wears boots, not a mask. Every criminal here knew cattle, talked bloodlines, and turned trust into a weapon. The threat isn’t outsiders—it’s people who belong.

- The cons age; the weak spots don’t. Saturday check scams in the 1920s. Counterfeit semen in the ’70s. Insurance arson in the ’80s. Show fraud in the ’90s. Same vulnerabilities, new generations.

- Red flags follow a pattern. Deals too sweet to question. Valuations that don’t match the animal. Pressure to move fast or skip verification. Multiple big losses in a short window.

- Boring habits beat brilliant schemes. Two signatures on major money. Written agreements before handshakes become partnerships. Chains of custody you can trace. A culture where anyone can say, “this doesn’t add up.”

- Know where you stop—before someone asks you to keep going. John Atkinson refused to sign a false claim. His father threatened his children. He lost the farm, but he kept his name. Draw your line now, while the pressure’s off.

The Chosen Breed and The Holstein History by Edward Young Morwick

Anyone who likes history, even in the slightest, will greatly appreciate either the US history (The Holstein History) or the Canadian History (The Chosen Breed) by Edward. Each of these books is so packed with information that they are each printed in two separate volumes. We had a chance to interview Edward – Edward Young Morwick – Country Roads to Law Office and you get a true sense of his passion and quick wit and they also come shining through in his books. Be sure to get your copies of amazing compilation of Holstein history in these books.

Continue the Story

- Show Ring Ethics: Cheater’s Never Prosper….Or Do They – This piece wrestles with the same heavy question that shadowed Wilcom and Wright, exploring how the relentless pressure of the high-stakes show ring can cause even the most talented breeders to let their ethics deteriorate when the banners feel more important than the truth.

- The Investor Era: How Section 46 Revolutionized Dairy Cattle Breeding – To truly understand the world Gordon Atkinson navigated, you have to look at the explosive tax-driven gold rush of the ’70s and ’80s, where a single line in the tax code turned dairy cows into Wall Street investment vehicles and sent valuations into a dangerous, unsustainable orbit.

- From Hoops to Herd Health: Dr. Sheila McGuirk’s Inspiring Journey from Farm Girl to Veterinary Trailblazer – Carrying the story forward into a more transparent age, this profile honors the trailblazer who fought to repair the industry’s weak spots, using science and an ironclad commitment to integrity to build the ethical safeguards that protect our show rings and our reputations today.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!