Nashville took him 5th overall. He was in the barn. ‘The cows don’t care if you’re drafted,’ he said. What his family did differently should make every farm parent think twice.

On the evening of June 27, 2025, the Nashville Predators selected Brady Martin fifth overall in the NHL Draft.

Brady wasn’t there.

He was in the barn at Creek Edge Farms, finishing the evening’s work alongside his brothers, just as he had every single day for as long as he could remember. The draft ceremony in Los Angeles—the red carpet, the cameras, the handshakes with NHL executives—had happened without him. He’d watched the broadcast from the milking parlor of his family’s 250-cow dairy operation near Elmira, Ontario, surrounded by the animals he’d cared for since childhood.

When reporters finally reached him and asked why he’d skipped what should have been the biggest night of his life, Brady’s answer was simple: “The cows don’t care if I’m drafted sixth or sixteenth. The morning milking starts at 5:30 AM.”

The family’s response to draft night captured everything about who they are. Being selected by an NHL franchise didn’t change a single thing about the next morning’s responsibilities. That was simply understood.

The following morning, Brady Martin—newly minted Nashville Predators prospect, eighteen-year-old with a three-year contract and more questions than answers about what comes next—was in the barn at 5:30 AM.

Because that’s what Martins do.

The Moment Everything Almost Fell Apart

To understand what the Martins built, you have to understand what they almost lost.

In 2023, sixteen-year-old Brady moved eight hours from home to Sault Ste. Marie to play for the OHL’s Greyhounds after being selected third overall in the Priority Selection. It was the opportunity he’d worked toward his entire young life. And within weeks, he was struggling.

“The first couple of months were tough,” Brady later admitted. He was lonely. He missed his family. He struggled to make friends in a new city where nobody knew him as anything other than “the new guy on the team.”

What happened next is the part of the story that still gets me.

Brady didn’t call home begging to quit. He didn’t push through with white-knuckled determination, pretending everything was fine. Instead, he called a family friend who lived near Sault Ste. Marie and asked a question that would have puzzled most teenagers: “Can I come do farm chores on your off days?”

Think about that for a moment. A sixteen-year-old, homesick and struggling, doesn’t ask to come home. He asks strangers if he can shovel their manure.

He wasn’t homesick in the conventional sense. He was experiencing something deeper—a disruption to his identity. The 5:30 AM chores weren’t just work he’d been assigned; they were part of who he was. Without them, he felt unmoored. Lost in a way that had nothing to do with geography.

The friend said yes. Brady started showing up on days off to feed cattle and do the unglamorous work that had structured his entire life. Within weeks, he’d stabilized. He started playing better. He made friends. He found his footing.

Sheryl Martin watched this unfold from 500 kilometers away and realized something she hadn’t fully understood before: the non-negotiable morning work she and her husband, Terry, had built into their children’s lives hadn’t been a burden Brady needed to escape. It was the anchor that kept him steady when everything else was uncertain.

The Mockery That Became Respect

Brady’s farm background didn’t always earn admiration. When he first entered the OHL, teammates weren’t sure what to make of the kid who talked about cows and couldn’t stay out late because he had to call home and check on the calving schedule.

“He took a little bit of a jabbing,” Sheryl recalls. “‘Oh, you’re a farmer—what does that even mean?'”

The ribbing escalated. During one game, a London Knights player named Landon Sim called Brady a “Mennonite” on the ice—an insult that earned him a five-game suspension. The mockery had crossed a line.

Most families would have advised Brady to downplay his background. Stop talking about the farm. Fit in. Don’t give them ammunition.

The Martins did the opposite.

During the playoffs, Sheryl organized a team visit to Creek Edge Farms. She smoked 45 pounds of beef, invited Brady’s entire team, and let them experience a working dairy farm firsthand.

“Most of the boys had never, ever been on a farm before,” Sheryl says. “They had no idea the function of a farm.”

Players who’d spent months teasing Brady about his background stepped off the bus into the smell of fresh hay and manure, the sound of cattle moving in the barn, the scale of an operation they’d never imagined. They held chickens—some for the first time in their lives. They watched Brady’s family work with the quiet efficiency of people who’ve done this work for generations.

Coach John Dean observed the transformation in real-time: “You could see him taking charge of things, caring for the smaller details, and he naturally fell into his rhythm—picking stuff up off the ground and moving gates. He wasn’t doing it to impress anybody—it was simply ‘This is what I do.'”

The teammates who’d been mocking him for months stood “completely wide-eyed.” Not all of them became converts overnight—some habits die hard—but the tone had shifted. Brady wasn’t the weird farm kid anymore. He was the kid whose family fed them 45 pounds of smoked beef and let them hold chickens. The jokes stopped. Players who’d skipped the visit regretted it.

In an industry often obsessed with being ‘misunderstood’ by the public, the Martins showed that the best way to be understood is to open the gate and feed people.

When the Parents Themselves Had Doubts

Here’s the part of the story that doesn’t make it into the highlight reels: even Sheryl and Terry questioned whether they were asking too much.

There were mornings—Sheryl admits—when getting teenagers out of bed at 5:30 AM required more persistence than any parent wants to muster. There were arguments. Slammed doors. Mornings when “I’m too tired” echoed down the hallway, and Sheryl had to decide whether this particular battle was worth fighting.

It always was. But that didn’t make it easy.

The system wasn’t magic. It was consistent, and consistency is exhausting.

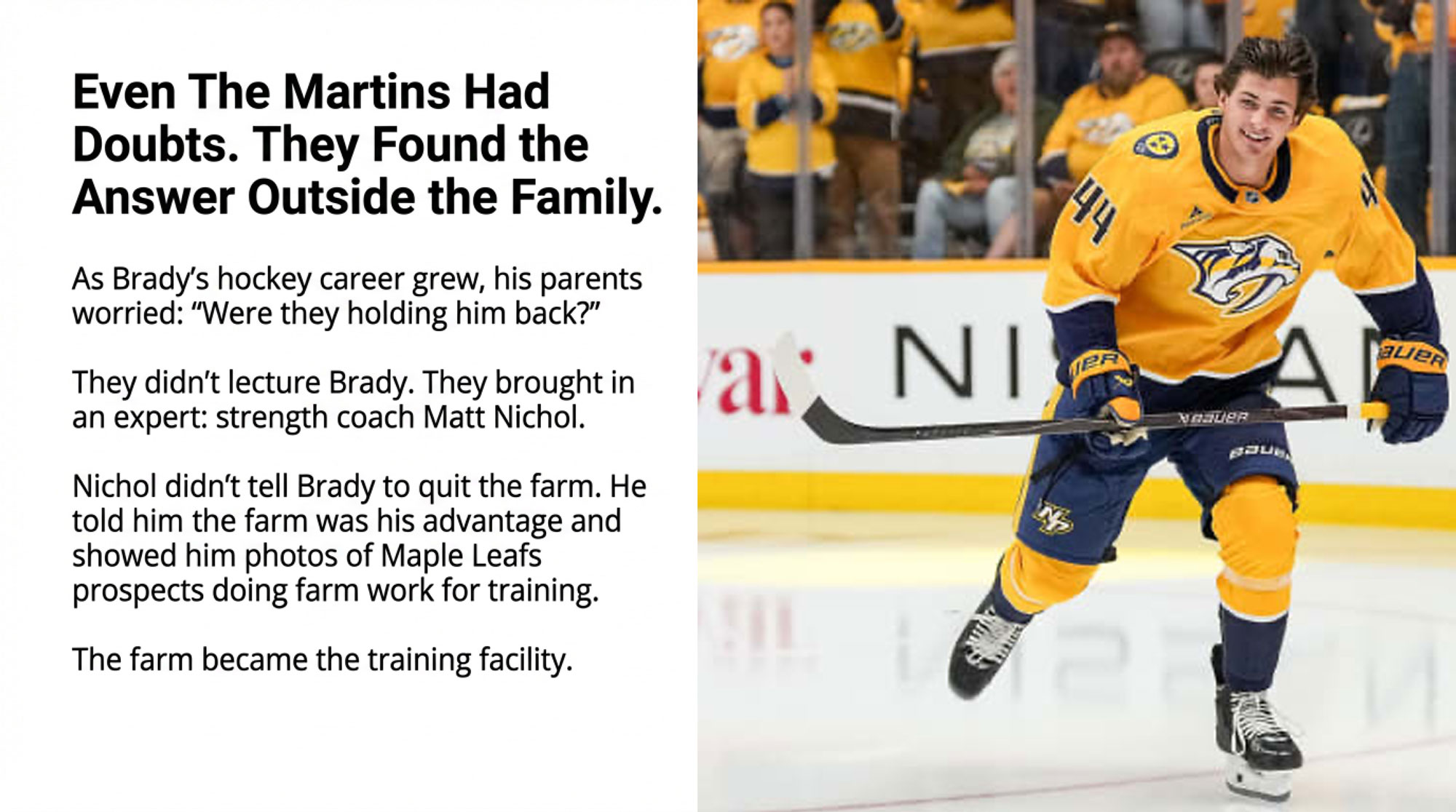

As Brady’s hockey career accelerated, as scouts started calling, as the demands on his time intensified, the Martins wondered: Were they being fair? Could their son actually succeed at the highest levels of professional sports while maintaining his farm responsibilities? Were they holding him back from his potential?

“They were worried,” Brady’s strength coach Matt Nichol later revealed. “‘Is he going to be able to still be at home and be on the farm and accomplish his goals?'”

When the doubt crept in, the Martins did something smart: they brought in an expert who could tell them the truth without bias.

Nichol’s assessment shocked them. The conventional wisdom—that Brady needed to leave the farm and train full-time at elite facilities—was wrong.

“The narrative on him was that he’d never worked out,” Nichol said. “I think he’d probably worked out more than most kids his age, just not in a gym.”

Instead of uprooting Brady from his agricultural life, Nichol designed programs that worked within it. He told the family about NHL legends who’d built their strength through manual labor. He showed Brady pictures of Maple Leafs prospects doing farm work as part of their training.

Then Sheryl Martin did what farm mothers do—she solved it herself. She pulled out the backhoe and built a training hill on the farm to the exact specifications Nichol recommended for professional development.

The farm didn’t adapt to accommodate hockey despite its limitations. The farm became the training facility that produced NHL-caliber results.

“Farm Strength”—The Competitive Advantage Nobody Saw Coming

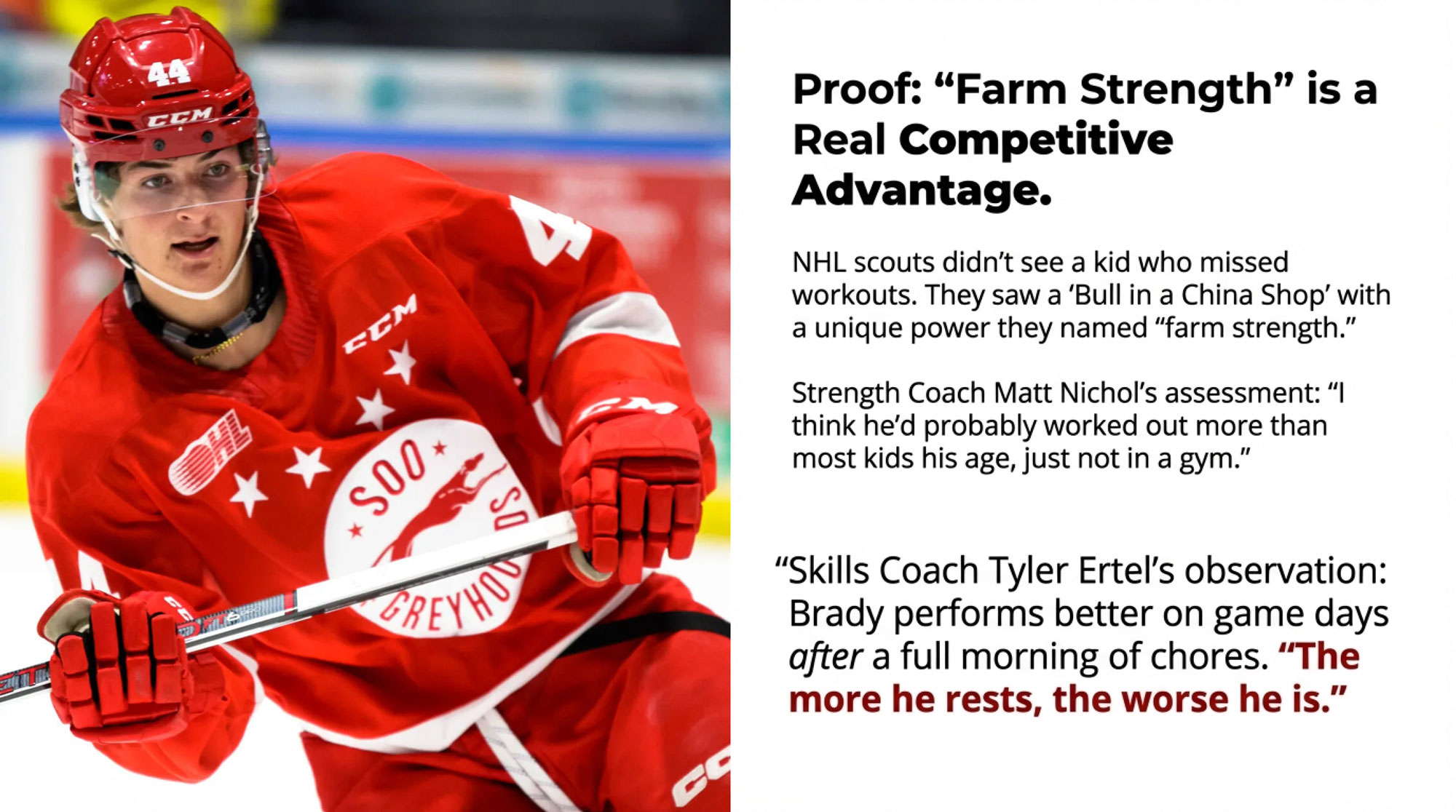

By the time draft day arrived, NHL scouts had a name for what Brady brought to the ice: “farm strength.”

Not gym strength. Not a training facility strength. Farm strength—the natural power, resilience, and work capacity built through years of daily physical labor that no amount of programmed workouts can replicate.

“Pound for pound, when he hits guys, the way he’s hard on pucks—that’s something he has come by completely naturally with his work on the farm,” Coach Dean explained.

Scouts compared him to Sam Bennett and Nazem Kadri—physical, relentless competitors who change games through sheer willpower and toughness. They called him a “Bull in a China Shop.” And in a detail that still makes his coaches shake their heads: Brady performs better on game days when he’s done a full morning of farm work first.

“The more he rests, the worse he is,” his skills coach, Tyler Ertel, observed. Ertel has worked with Brady since he was nine years old and lives just nine minutes from Creek Edge Farms—close enough to witness the connection between barn work and ice performance firsthand.

In one tournament game on the way to the OHL Cup, Brady put in a complete morning of barn work, then drove to the city and scored a hat trick against the top-ranked team in the province.

This isn’t to say the path came without trade-offs. Brady missed hockey camps. He arrived at some tournaments with less rest than competitors who’d spent the previous day in recovery protocols. But somehow, for him, the equation worked differently. The farm work wasn’t draining him. It was fueling him.

The Sibling Infrastructure Most People Miss

The most overlooked part of this story isn’t the draft pick. It’s the sibling infrastructure that made it possible.

Sheryl and Terry Martin raised four children—Joey, Brady, Jordan, and youngest Rylee—each with the same expectations, each finding their own balance between farm responsibility and individual pursuits. Joey, the eldest at nineteen, has taken on primary responsibility for the farm’s day-to-day operations during hockey season. Jordan, at sixteen, handles his own substantial workload while still in high school. Both covered for Brady during the stretches when his hockey schedule made full farm participation impossible.

The family operates on what amounts to an annual ledger rather than a daily one. Fairness isn’t measured by equal work on any given day—it’s measured by everyone contributing fully over the course of a year, with flexibility for individual circumstances. Brady goes hard in the summer when hockey pauses. His brothers shoulder more of the workload during the winter months.

The balance works out—though that’s not to say there’s never friction. When schedules collide or workloads feel uneven, the tension surfaces like it does in any family. But they work through it, usually over breakfast, always with the understanding that they’re building something together.

When the three brothers launched their beef cattle enterprise during COVID—”We were all stuck at home, so I went and bought some cows,” Brady recalls with characteristic understatement—they became business partners, not just siblings doing chores.

That beef enterprise has since “taken on a life of its own.” During the flurry of NHL interviews surrounding the draft, Brady was simultaneously auctioning cattle for the family operation. One reporter caught him juggling calls from hockey executives and livestock buyers in the same afternoon.

Joey and Jordan aren’t waiting for Brady’s hockey career to end. They’re building something alongside him. And that shared ownership changes everything about how they view the work.

The Uncomfortable Truth Most Farm Parents Won’t Hear

Here’s where I’m going to say something that might sting: most farm families are doing this backwards.

The Martins didn’t set out to create a replicable system. They were just trying to raise good kids who understood the value of hard work. Terry Martin gave Brady a single line that became his operating principle: “Hard work is the biggest thing, and if you’re working hard, good things will come.”

But what they discovered exposes a pattern that’s killing farm succession across North America.

The conventional approach to farm family scheduling treats external activities as fixed and farm work as flexible. Soccer practice is at 6 PM, so chores get squeezed in “when there’s time.” Tournament weekends mean someone else covers the barn. School, sports, friends—all non-negotiable. Farm work gets whatever scraps of time remain.

Every time you negotiate away the chores, you’re teaching your kids that the farm is the least important thing in their lives.

Let that sink in.

When you say, “skip the morning milking, you’ve got a big game,” you think you’re being supportive. You think you’re helping them succeed. What you’re actually doing is confirming what they already suspect: the farm is an obstacle to their real life, not the foundation of it.

The Martin family flipped this entirely.

Farm work is the fixed point around which everything else orbits.

When farm work is non-negotiable—when it happens at 5:30 AM regardless of what game was played last night—kids learn something different: this is who we are. This is the foundation. Everything else gets built on top of it.

Brady Martin didn’t become someone who “has to do chores.” He became someone who does chores. Identity, not obligation. That distinction made all the difference.

And before you tell me your operation is different, that your kid’s travel schedule is too demanding, that you can’t afford to be inflexible—ask yourself this: are you raising a kid who will come back to the farm, or are you raising a kid who can’t wait to leave it?

For Families Without 250 Cows

I need to be honest about something: the full Martin framework requires certain prerequisites—enough scale to absorb seasonal flexibility, strong management, and genuine profitability. Not every operation can implement the complete rotation system.

But here’s what any family can do, regardless of scale: recognize that external validators matter more than parental lectures.

Brady didn’t decide farm work was valuable because his parents told him so. He decided it was valuable because NHL scouts called it “farm strength,” because his strength coach said he’d already out-trained most athletes, and because his teammates visited Creek Edge Farms and left transformed.

The Martins didn’t convince their son. They connected him with people whose opinions he respected—and let them do the convincing.

If your teenager thinks farm work is competing with their goals, here’s the single highest-leverage action you can take: arrange one 15-minute phone call between your kid and someone in their field of interest who grew up on a farm.

Not mentorship. Not career counseling. Just one question: “When did you realize your farm background was actually an advantage in your career?”

Find that person through LinkedIn, through the FFA’s Forever Blue Network, or simply by texting your veterinarian: “Do you know anyone in engineering—or nursing, or business—who grew up on a farm?”

That 15-minute conversation can accomplish what years of parental lecturing cannot. Because kids can’t hear this message from us. We’re too biased. We need them to do chores, so of course, we say chores are valuable.

But when someone with no stake in your operation tells your kid, “Farm work is why I got hired,”—they believe it.

Will this work every time? No. Some teenagers are determined to see farm work as punishment, no matter what anyone says. But for the genuinely uncertain kids—who haven’t yet decided what the farm means to them—external validation can tip the scales.

The Legacy Being Built

In Nashville’s development camp after the draft, Brady Martin showed up as the only first-round pick who’d never attended a formal hockey training facility. The other prospects had spent years in elite programs with specialized coaches and state-of-the-art equipment.

Brady had spent those same years at Creek Edge Farms. On a tractor. Building fences. Chasing escaped cattle. Waking at 5:30 AM every morning because that’s when the cows needed milking.

And somehow, that unconventional path had produced exactly what professional hockey demands: a player with elite strength, unusual mental toughness, unshakeable work ethic, and the quiet confidence that comes from knowing you’ve already done harder things than anything a game can throw at you.

By October 2025, Brady had made Nashville’s Opening Night roster—one of the youngest players in the league. He played three NHL games before being sent back to the OHL for further development, a standard path for eighteen-year-olds with long careers ahead of them.

When reporters ask Brady about life after hockey, his answer never wavers: “Hopefully I play in the NHL. But if that doesn’t work out, then the farm is definitely where I’ll be heading.”

Notice what he’s saying. The farm isn’t his backup plan if hockey fails. It’s his destination. Hockey is the temporary—if spectacular—detour.

The Martin family didn’t set out to create an NHL player. They set out to raise children who understood the value of hard work, the dignity of agricultural responsibility, and the irreplaceable satisfaction of building something real with your hands.

That Brady also became a first-round draft pick is almost beside the point.

The real achievement is raising kids who—given every opportunity to leave, every excuse to prioritize themselves, every reason to see the farm as something to escape—chose to stay connected to the land and animals that shaped them.

The Bottom Line

On the morning after the biggest night of his life, Brady Martin was in the barn at 5:30 AM. Not because anyone made him. Because that’s who he is.

The cows don’t care if you’re drafted sixth or sixteenth. They need milking at 5:30 AM.

And in that simple, stubborn, beautiful fact lies everything you need to know about raising kids who achieve extraordinary things—and still choose to come home.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Make farm work the fixed point: The Martins built their schedule around 5:30 AM chores, not around hockey. Everything else orbits the barn. Reverse this, and you’re already teaching your kids to leave.

- “Farm strength” is a real advantage: NHL scouts named it. Strength coaches confirmed it. Daily physical labor builds something no elite training facility can replicate—and Brady performs worse when he rests more.

- Identity over obligation: Brady didn’t become someone who “has to do chores.” He became someone who does chores. That single distinction determines who comes back and who can’t wait to escape.

- Stop negotiating away the chores: Every time you say “skip the milking, big game today,” you confirm what your kid already suspects—the farm is an obstacle to their real life, not the foundation of it.

- Use external validators: Your teenager can’t receive this message from you. One 15-minute phone call with a professional who grew up on a farm accomplishes what years of your lectures never will.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

Brady Martin was drafted fifth overall by Nashville in 2025. He wasn’t at the ceremony—he was in the barn at 5:30 AM, same as every other day. Scouts called it “farm strength.” His family called it non-negotiable. The Martin system is brutally simple: farm work is the fixed point around which everything else orbits. Most families do the opposite—making chores the flexible thing that gets sacrificed for games and practices—then wonder why their kids can’t wait to leave. The Martins held the line through slammed doors, teenage arguments, and their own doubts. Result: four kids building a beef enterprise together, one of them in the NHL, all of them coming back. The lesson every farm parent needs to hear: your kids can’t receive this message from you. Find someone in their field who grew up on a farm and arrange one 15-minute call. External validation beats parental lectures every time.

Learn More

- The Family Farm Time Bomb: Why 83% of Dairy Operations Won’t Survive (And What Smart Producers Are Doing About It) – Secure your Monday morning ROI by implementing five data-driven management shifts that defuse succession drama. This breakdown arms you with the genomic and technology benchmarks required to transform emotional family conversations into profitable business decisions.

- Four Farms Exit Daily: The $100K Decision Reshaping Dairy Survival – Stop gambling on high-intensity labor and start positioning your equity for the next five years. This analysis delivers the structural math needed to navigate a market where scale and specialization are now the only survivors.

- How Dairy Farmers Are Finally Breaking Free From the 365-Day Grind – and Finding More Time and Profit – Leverage automation as your ultimate recruitment tool to secure the next generation’s interest. This field report exposes how cutting labor hours in half isn’t just about efficiency—it’s about creating a lifestyle that actually attracts successors.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.