Don’t send that kid back.” One phone call nearly killed Brian Coyne’s career before it started. He’s now Manager of Applied Genetic Strategies at Select Sires.

Executive Summary: Don’t send that kid back.” One phone call nearly ended Brian Coyne’s dairy career before it started. Today, he leads genetic strategy at Select Sires. Kylene Anderson took a temp job nobody wanted—it became her runway to managing editor at Hoard’s Dairyman. Amanda Lichtensteiger lost count of the “we chose someone more experienced” emails in 2009; now she runs dairy strategy at Diamond V. At World Dairy Expo 2025, these three revealed what actually builds careers: character that can’t be taught, sponsors who fight for you in rooms you’re not in, and the guts to choose the right barn over the right title. Your five-year plan might be in shreds. These stories suggest that’s exactly where the best careers begin.

In that moment, the room went quiet.

It was the Uplevel Dairy Podcast‘s live panel from the National Dairy Shrine Young Professionals luncheon at World Dairy Expo 2025, and a young genetic strategist named Brian Coyne was describing something most people in agriculture don’t talk about—the day everything almost ended before it began. His first solo day running farm calls in southeast Wisconsin. A visit that didn’t go well. And then the call from his boss with news that still stings when he tells it: the producer had phoned the office and made it clear—don’t send that kid back.

Even through the recording, something landed. Maybe it was the pause before he continued. Maybe it was recognizing my own version of that truck-seat moment—the gut punch, the silence afterward, wondering if maybe you’re just not cut out for this after all. Either way, the story cut through.

What moved me most wasn’t that Brian shared the rejection. It’s what he did with it. He decided that one bad visit, one angry call, one awful knot-in-the-stomach moment wasn’t going to rewrite who he was or why he came to this industry in the first place.

Alongside Brian on that panel were Kylene Anderson, who stepped into the managing editor role at Hoard’s Dairymanin January 2025, and Amanda Lichtensteiger, who now leads strategic marketing for Diamond V within Cargill’s animal nutrition business. Each of them opened up about the moments when their carefully drawn five-year plans cracked—or completely fell apart—and how the detours, not the straight lines, shaped the work they do for farmers today.

Listening to the full conversation, what struck me wasn’t that this was a motivational talk. It was three grounded dairy people pulling back the curtain on failure, “wrong” jobs, sponsorship, and the kind of character that matters far more than a perfect résumé. Their stories are worth sitting with—especially if your own plan isn’t going the way you thought it would.

The Day the Plan Dies

The way Brian described it to the panel, everything about that first solo farm call felt slightly off. An unfamiliar layout. Small talk that didn’t quite land. That creeping sense, as he walked back to his vehicle, that the producer wasn’t buying what he was saying.

And then the confirmation came—not from the farmer, but from his own office. The answer was in. And it was no.

This was supposed to be the beginning of everything. After working as a herd manager on three different dairies for about two and a half years and a short breeding stint, he’d landed a position at what was then East Central Select Sires—now Central Star Cooperative—running matings for roughly 300 herds across southeast Wisconsin, helping plan tens of thousands of breedings a year. He’d worked for this. He’d pictured it. In any standard five-year plan, that first day was meant to be a milestone, not a gut punch.

He didn’t frame it as a learning experience immediately—probably nobody does. But somewhere between that farm lane and the next call on his schedule, he made a choice. Instead of treating that rejection as a verdict on his worth, he started treating it like very expensive tuition. He asked himself what went wrong, what he’d missed, what he needed to learn before the next farm call.

And then, quietly, he made a decision that would set the tone for his entire career: he was going to keep showing up.

I’m not sure how you find that kind of resolve when you’re twenty-something and the first real test of your career has just blown up in your face. Something inside him refused to quit. Maybe it was stubbornness. Maybe it was that bone-deep conviction that he was meant to help farmers breed better cows. Whatever it was, it held.

Within a few years, Brian wasn’t the rookie getting turned away from a farm; he was the one training others how to handle tough calls and overseeing mating programs for thousands of cows. In 2019, Select Sires hired him to relocate to their headquarters in Plain City, Ohio—where North America’s largest A.I. organization is based—to help design their bull search and genetic consulting tools. By April 2024, he’d been promoted to Manager of Applied Genetic Strategies, leading a team that supports producers around the world and managing global genomic testing partnerships with Zoetis and the French company Lavoena.

Since then, on more than one farm visit, he’s watched those tools help producers tighten up calving intervals, improve daughter fertility, and sort through genomic data that used to feel overwhelming. One producer told him their replacement heifer program finally started making sense after years of guesswork—the kind of feedback that reminds you why the early stumbles were worth pushing through. The very experience that once made him question if he belonged in this work now informs the way he builds systems that make farmers’ lives a little easier.

During the panel, he and the other speakers discussed something that’s stayed with me: the idea of reframing setbacks not as permanent failures but as part of the process—stumbling, adjusting, getting back up. It’s the kind of thing kids do dozens of times a day without keeping a tally. They just try again.

What’s remarkable is how closely that lived experience lines up with what researchers are finding. A major study from Northwestern University, published in Nature Communications, followed early-career scientists and discovered something counterintuitive: those who experienced significant early setbacks—but stayed in the game—often went on to outperform those who enjoyed easy early wins. The “near-miss” group showed a 6.1% higher likelihood of publishing top-cited papers over the following decade. Failure didn’t magically make them better. What made the difference was how they responded—by reflecting deeply, adjusting course, and building the kind of grit you can’t buy.

That morning in the farm lane was not a feel-good moment. It still isn’t, when Brian talks about it. But somehow, it became a turning point. It was the day he chose to let failure serve as tuition rather than a final grade.

The Job Nobody Wanted—And Why She Took It Anyway

Listening to the panel recording, I could hear Kylene Anderson laugh gently as she described the job that sparked her whole career shift. It wasn’t glamorous. It wasn’t permanent. And it definitely wasn’t what most people would have posted about on LinkedIn.

After graduating from the University of Wisconsin–Madison with degrees in dairy science and agricultural journalism, Kylene pursued her love of international agriculture in Mexico, working with UW’s international egg programs. When she came home, she needed a paycheck and still carried a deep pull toward the dairy genetics world.

ABS Global had always been on her radar. It was one of those “if I could just get in the door there…” companies. When they offered her a temporary role covering maternity leave—a support position outside the flagship genetics division—she knew exactly where it sat in the company hierarchy.

“Nobody thinks of ABS and immediately thinks of that product line,” she admitted. It got a laugh from the crowd, but you could hear the honesty beneath it.

On paper, it looked like a step down from what her five-year plan might have promised—temporary, not in the core business, and not clearly leading anywhere beyond a few months.

Was it a risk? Of course. There was no guarantee the role would lead anywhere. She could have held out for something that looked better on paper, something that matched what she’d told people she was looking for.

But Kylene wasn’t optimizing for appearances. She saw a building full of people shaping global breeding decisions. She saw sales teams, marketers, geneticists, and field staff she could learn from. Most of all, she saw a chance to move from the outside to the inside of a company she deeply respected.

So she took the job that almost everyone else would have filtered out.

Day to day, that meant answering calls about products that weren’t the company’s headline offerings, traveling to meetings that weren’t always in the limelight, and learning the rhythms of ABS from a vantage point few envied. But behind the scenes, something far more strategic was happening. Sales colleagues learned she could be counted on. Marketing saw that she wasn’t just pushing product; she was connecting it to real herd needs.

She still remembers the first time a senior leader pulled her into a planning conversation that had nothing to do with her job description—not because she’d asked, but because someone had noticed how she approached her work. Small moments like that add up. Leaders started to recognize her name and her work ethic.

Over time, that temporary role grew into a decade of positions spanning ABS and the livestock marketing agency Filament Marketing in Madison, Wisconsin, then back to ABS in higher-level global dairy and beef genetics marketing work. In January 2025, she stepped into the managing editor role at Hoard’s Dairyman—the publication founded in 1885, now marking its 140th year—essentially circling back to the journalism roots of her college days, this time carrying a decade of field and industry experience.

What struck me, hearing her tell it, was how clearly she now sees that early choice. It wasn’t a demotion. It was a decision to prioritize access over prestige, building over label.

Her career has rippled back out to farms, too. Today, as an editor, she gives space to the stories of young producers, women in dairy, and small family herds whose voices might otherwise be drowned out—stories that, in turn, give other farmers ideas and courage in their own operations.

That lens matters more than ever. Today’s agriculture and food employers say they’re leaning hard into internal mobility and development because hanging onto people who deeply understand farming has become critical in a tight labor market. For a young person, that means the job that looks “less than” might actually be the smartest move—if it puts you shoulder-to-shoulder with the right people in the right culture.

The entry-level job nobody wanted became Kylene’s runway.

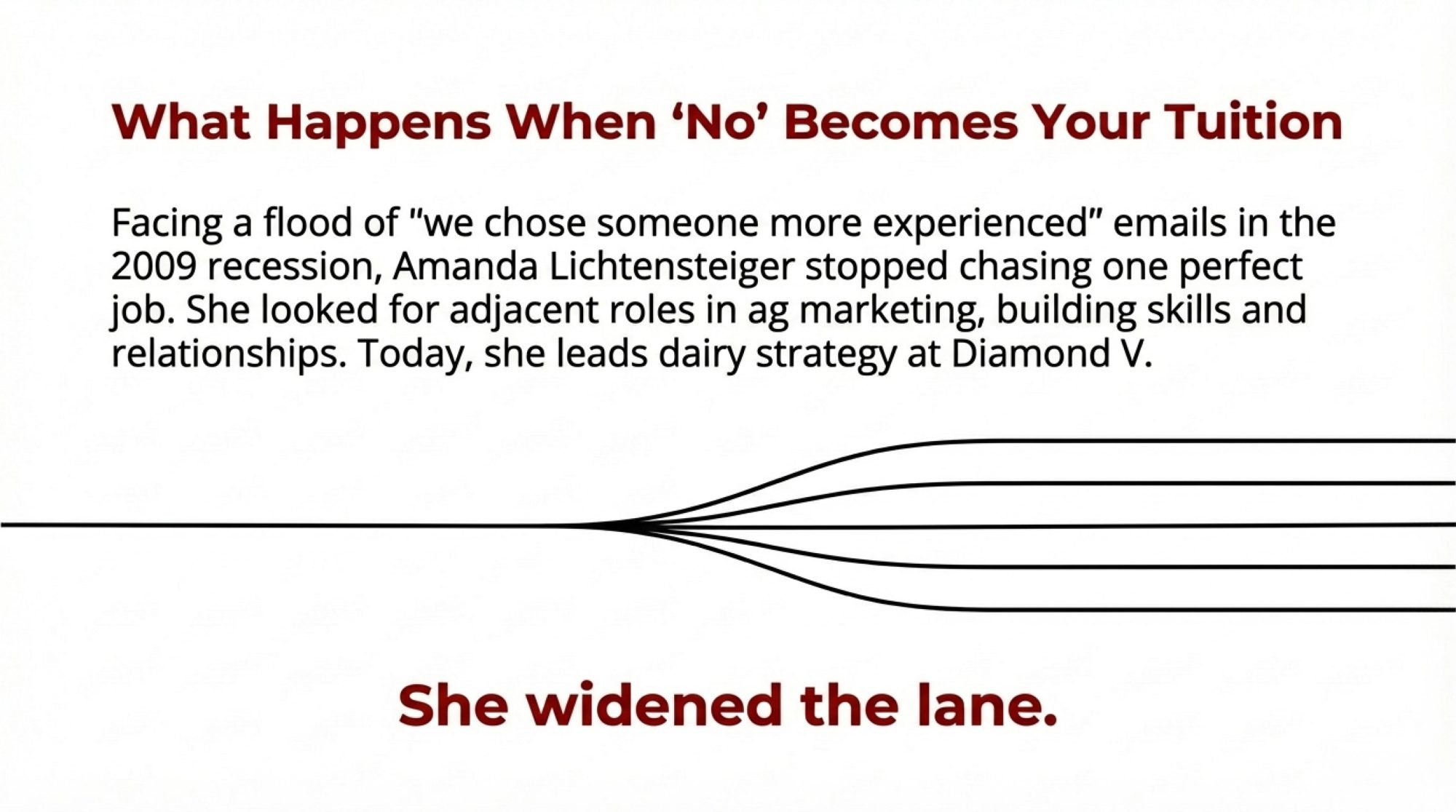

When the Job Market Says “No” Again and Again

Nobody listening to that panel needed to be told 2009 was a rough year to launch a career. But hearing Amanda Lichtensteiger walk through it was still sobering.

She grew up on a dairy farm in Monroe, Wisconsin—learning early what it meant to get up before dawn, to see cows as individuals, and to watch her parents ride out good and bad years the way only farm families do. Maybe those early mornings taught her something about showing up even when you don’t feel like it. Maybe watching her family push through tough seasons planted something she wouldn’t fully understand until later.

She crossed the border to the University of Minnesota, did everything people tell you to do—internships, networking, solid grades—and set her sights on agricultural communications.

What she walked into after graduation was a job market still reeling from recession, flooded with applicants who had decades more experience. Time after time, she made it to the final round, only to hear a polite variation of, “We loved you, but we chose someone more experienced.”

From the outside, that just sounds like bad timing. From the inside, it can feel like erosion—one “almost” at a time.

What nobody tells you is how personal it starts to feel, even when you know it isn’t. You start second-guessing cover letters you were proud of. You wonder if there’s something in your interview presence that people can see and you can’t. Amanda didn’t say all of this explicitly, but you could hear it in the way she paused before describing what came next.

What changed everything for Amanda wasn’t a single big break; it was a decision, somewhere in that difficult season, to stop insisting that the job market fit her script. Instead, she began exploring roles adjacent to what she thought she wanted. In September 2009, she stepped into an account coordinator role at Charleston|Orwig in Milwaukee—she still remembers that Mike Opperman was the first person to hire her out of school. From there, she moved to Bader Rutter & Associates, supporting animal health and dairy accounts for multiple clients, and later moved into corporate roles in ruminant additives at Lallemand before joining Cargill in May 2020. By August 2024, she’d been named Strategic Marketing Lead for Dairy at Diamond V.

Along the way, she picked up something you can’t learn in a classroom: how products actually move through the value chain, how global markets shift, and how different teams—from R&D to on-farm sales—have to pull together to make a difference for producers. She also built relationships that would echo later, including with a leader who eventually became a key sponsor, hiring her into new opportunities more than once.

On the farm side, the programs she now helps shape for gut health and immune support have been adopted by dairies seeking to reduce health events and improve herd consistency. The ripple effect of those early, painful “no’s” now shows up in healthier cows and more resilient operations.

What impressed me most, listening to her tell it, was that she didn’t spin that early season into a hero story. She described it honestly as frustrating and stretching. But she also recognized, looking back, that it taught her to widen the lane—to look beyond the one role she’d imagined and ask, “Where else could my skills serve this industry I love?”

Today, when she sits on the hiring side of the table, she carries that memory with her. She knows what it feels like to be one of many in a stack of résumés. She also knows firsthand that some of the best long-term fits come from candidates who were willing to step into roles that didn’t match their original five-year plans—but that did match their values and curiosity.

When Character Beats the Résumé

What happened next in the discussion surprised me with how practical it felt. They’d been talking about failures and detours. Then the conversation turned to a blunt question: what actually gets someone hired or promoted now?

Amanda shared that at Cargill and Diamond V, they lean heavily on a framework called the “ideal team player” when evaluating candidates: humble, hungry, and people-smart. Humble, as in willing to admit gaps and learn from them. Hungry, as in self-driven and ready to dig in. Smart, not just intellectually, but in reading people, listening, and collaborating.

Brian described something similar at Select Sires. They can teach a new hire to run a genomic report or navigate a mating program. They can’t teach them to tell the truth when it’s hard, genuinely care about the producer’s reality, or own up to a mistake and fix it. Those traits only show up over time: in how someone dresses and prepares for an interview, whether they follow through on small tasks, and how they talk about the farmers and teammates in their stories.

Across agriculture, this isn’t just a hunch. Surveys of employers in the ag and food sectors consistently show that communication, problem-solving, and teamwork outrank narrow technical skills as top hiring priorities, especially for early-career roles. At the same time, dairy employers say retention and culture have become central survival strategies—they want people who strengthen their teams, not just fill slots.

One quiet but powerful takeaway for farm owners: when you’re hiring or promoting on your own operation, don’t just ask, “Can this person feed cows or run the parlor?” Ask, “Is this the kind of person I want representing our family name? Will they tell me the truth? Will they keep learning?”

Those are character questions. And in 2025’s dairy world, they’re career questions too.

The Quiet Power of Mentors and Sponsors

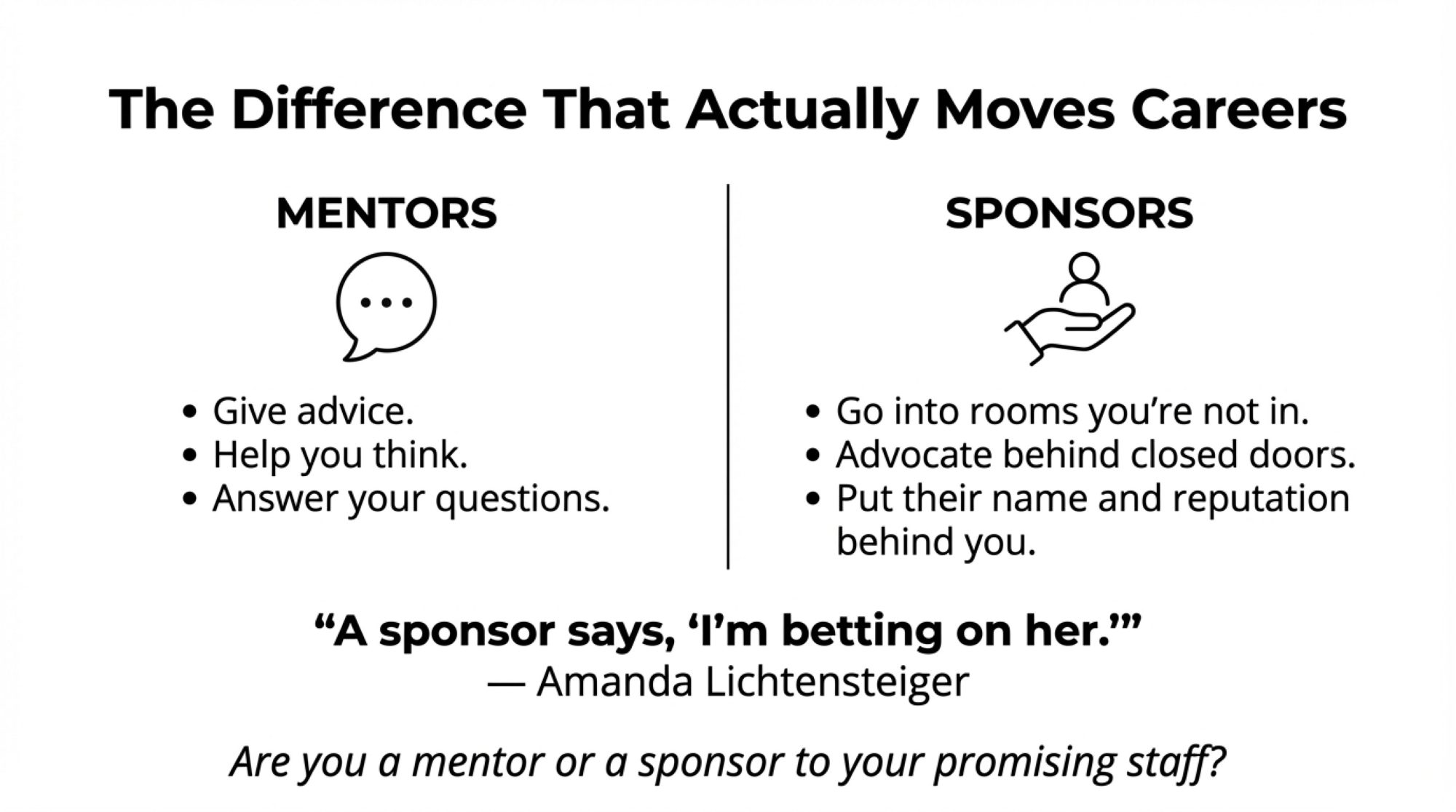

The moment that really shifted the conversation came when Amanda drew a line most young professionals never see clearly: the line between mentors and sponsors.

A mentor, she explained, is someone who helps you see yourself and your options more clearly. They answer your questions, help you think through your decisions, and offer advice based on their own experience.

A sponsor is something different—and rarer.

“A sponsor is a more senior person who goes into meetings you’re not in and brings your name up when it matters. They advocate for you. They say, ‘I think she can do this. I’m willing to put my reputation behind her.'”

— Amanda Lichtensteiger, Strategic Marketing Lead for Dairy, Diamond V

In Amanda’s own journey, one leader who first knew her in agency work later hired her again into a corporate role. He didn’t just encourage her; he actively created opportunities based on years of watching her work and integrity.

Research from workplace studies backs this up: employees who can name both mentors and sponsors report higher engagement and are more likely to advance than those who have mentors alone. Sponsorship, in particular, appears to be a key ingredient in helping capable people move into roles they might never access through applications alone.

What I found extraordinary, listening to the panelists, was how they framed this for the students in the audience. None of them suggested that you march up to someone and ask, “Will you sponsor me?” Instead, they stressed that sponsorship is earned, not requested. It grows out of doing consistently good work, building trust over time, and staying connected so that when a leader thinks, “Who’s ready for this next challenge?” your name naturally comes to mind.

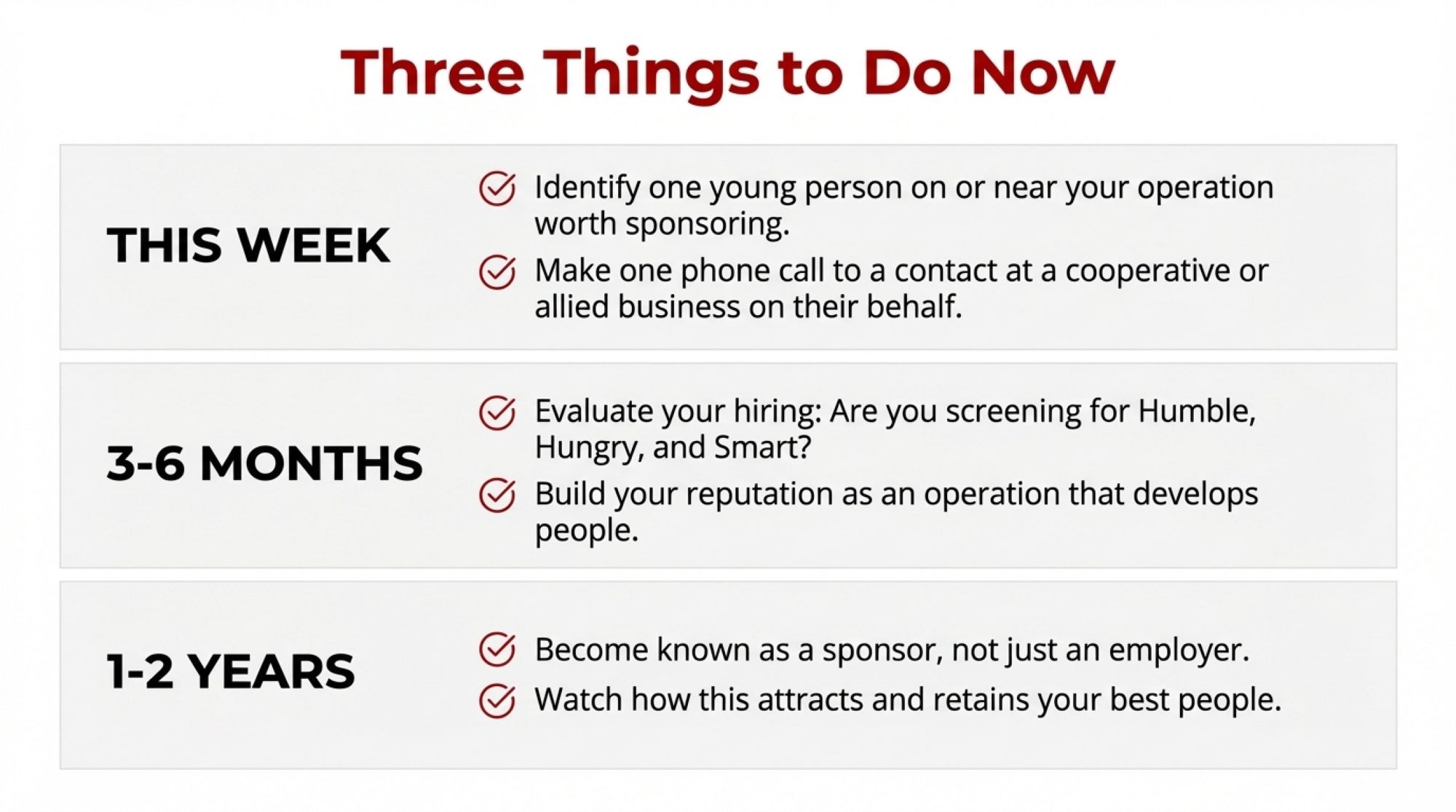

For dairy farm owners, there was another angle worth considering: sometimes the most powerful thing you can do is become a sponsor yourself. Not just coaching a promising herdsman or calf manager, but quietly calling a contact at a cooperative, genetics company, or allied business and saying, “I’ve got someone here who’s ready for more. You should talk to her.” That’s how this next generation moves.

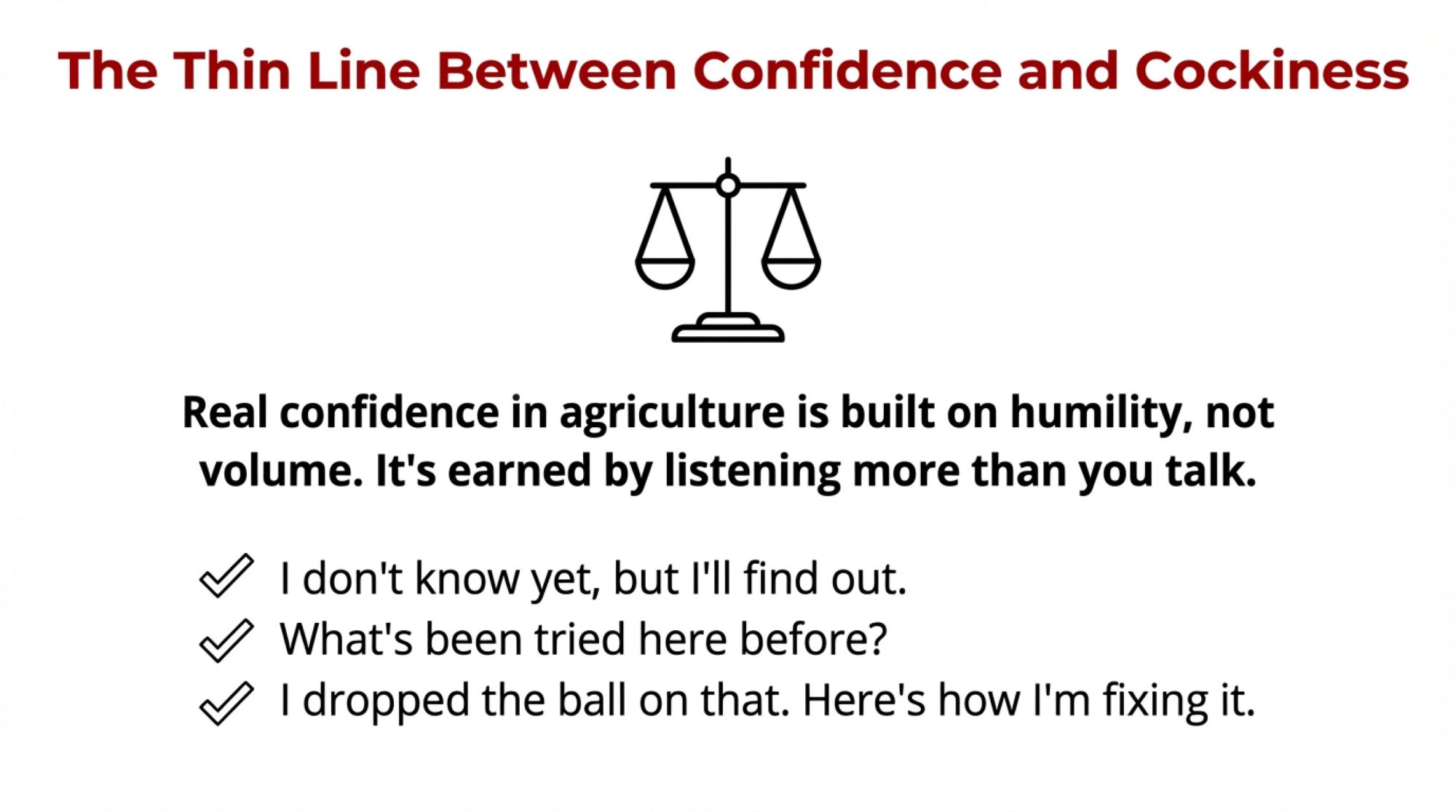

Confident Humility: Getting Noticed for the Right Reasons

Later in the conversation, Brian shared a line that landed hard: he’s seen many times that confidence without context quickly turns into cockiness.

We live in a moment where young professionals are told to “stand out” and “sell themselves.” But in a parlor, at a kitchen table, or across a hiring interview, there’s a thin line between confidence and arrogance—and producers, frankly, can smell the difference before you’ve finished your first sentence.

What changed everything for Brian, and what Amanda echoed, was understanding that real confidence in agriculture is built on humility, not volume. Amanda said her own confidence comes from being willing to be humbled—failing, seeking feedback, and doing the slow work of improving—rather than from having all the answers on day one.

Brian encouraged the students to think of their first three to seven years not as a rush to management titles, but as a dedicated learning season. To walk into barns and meeting rooms less focused on proving they belong and more focused on understanding the cows, the numbers, the families, and the systems in front of them.

In practice, that looks like:

- Saying, “I don’t know yet, but I’d like to find out,” and then actually coming back with a thoughtful answer.

- Asking, “What’s been tried already?” before suggesting a fix.

- Owning it when you drop the ball—and then fixing it.

Studies on agricultural workplaces highlight that employees who can accept feedback, adapt, and stay composed under pressure are exactly the ones organizations fight to keep. That blend of quiet strength and teachability is what sponsors look for when deciding who to back, and what producers look for when deciding who to trust.

What moved me most here was how freeing this is. You don’t have to pretend you’ve got it all together. You do have to care enough to keep learning.

Field-Tested Truths to Carry Home

By the time the Q&A wrapped up, you could hear in the recording that something had shifted. Nobody handed out a worksheet at the end. But if you’d been taking notes—and I was—certain threads kept surfacing. Not as slogans, but as the kind of hard-won wisdom you only get from people who’ve actually been through it.

Treat failure like tuition, not a final grade.

Brian’s worst first day wasn’t a verdict; it was expensive tuition for a lesson he still lives by. The Northwestern study on early-career setbacks suggests that for those who persist and adjust, stumbling early can actually lead to stronger long-term outcomes than easy early wins. The difference is whether you walk away or lean in and learn.

Choose the right barn over the right title.

Kylene’s temporary role at ABS looked like a step down to some, but it put her in the building she wanted to learn from—and close to the people who later opened bigger doors. In an industry where internal retention and development are now strategic priorities, being in a culture that fits you matters more than starting with an impressive label.

Let your work make you visible; let your humility make you trustworthy.

The people who got sponsored in these stories weren’t the loudest; they were the ones who did excellent work and paired it with grounded humility. Employers repeatedly rank soft skills—reliability, communication, problem-solving—above narrow technical abilities for entry roles, precisely because those traits make someone safe to trust with more.

Build relationships before you need them.

Amanda’s sponsor didn’t appear out of nowhere when she needed a job. He knew her from earlier collaborations, saw her consistency, and remembered her when opportunities surfaced. The time you spend getting to know people at World Dairy Expo, in committees, or through internships isn’t extra—it’s the fabric your next steps can hang from.

Accept that non-linear paths are normal—and often stronger.

The panel’s careers didn’t climb neatly; they zigzagged. In dairy, where markets, technology, and regulations can all shift in a season, flexibility is not a flaw; it’s a survival trait.

What This Means for All of Us

What stayed with me long after the recording ended wasn’t that Brian ended up at Select Sires’ headquarters in Ohio, or that Kylene now holds the editor’s chair at Hoard’s Dairyman, or that Amanda leads strategy for one of the most recognized names in animal nutrition. It was that each of them got there by living through seasons that, at the time, looked a lot like failure.

Brian, replaying a disastrous farm call and wondering if he was cut out for this.

Kylene, staring at a job description for an entry-level support role and choosing it anyway because of where it might lead.

Amanda, opening yet another email that politely said “not this time,” and deciding she would look sideways rather than give up.

Their stories aren’t fairy tales. They’re proof that in dairy—as on a farm—what looks like a wrecked year can, with patience and a willingness to adjust, become the season you later point to and say, “That’s where everything shifted.”

Many of the people listening to that panel grew up the same way they did: watching parents and grandparents ride out low milk checks, equipment breakdowns, droughts, or processor cuts with the same stubborn rhythm—get up, feed cows, fix what you can, and try again tomorrow. That same spirit runs through these careers. It’s just wearing different clothes.

For farm owners, there’s a challenge here too. Somewhere on your team or in your local 4-H or collegiate club is a young person who has just had their own version of Brian’s difficult first day, or Kylene’s “lesser” job offer, or Amanda’s stack of polite rejections. You might be the one who helps them see it as a toll booth, not a stop sign. You might be the mentor who listens, or the sponsor who makes a quiet call and says, “You should give this kid a look.”

And if you’re that young person—if you’re reading this after a bad day in the parlor, an interview that went nowhere, or a shift into a role that feels “less than” what you pictured—hear this clearly: you are not behind. You are standing exactly where a lot of us started.

Your five-year plan might be in shreds. That doesn’t mean your story is. It might mean your story is just getting honest.

I don’t know what your version of Brian’s farm call or Kylene’s temp role, or Amanda’s stack of rejection emails looks like. But if you’re in the middle of one right now, here’s what I keep coming back to: the people on that panel didn’t sound like they’d figured everything out. They sounded like people who’d figured out how to keep going—and who were still learning.

That’s not a small thing. That might be the whole thing.

Now I’m curious: Who is the young person in your operation, your community, or your 4-H club who needs someone to believe in them right now? And what’s stopping you from making that call today?

Key Takeaways

- Treat failure like tuition, not a verdict. Brian Coyne got rejected on his first farm call. Today, he leads genetic strategy at Select Sires. He didn’t get lucky—he refused to stop showing up.

- Pick the right barn over the right title. Kylene Anderson took a temp job nobody wanted. It put her inside ABS when it mattered. A decade later: managing editor at Hoard’s Dairyman.

- Sponsors beat mentors—find one, become one. Mentors give advice. Sponsors walk into rooms you’ll never see and say, “I’m betting on her.” That’s the difference that moves careers.

- Character can’t be trained. Companies teach genomics and marketing. They can’t teach honesty, follow-through, or the guts to own your mistakes. Lead with those.

- Your five-year plan is supposed to break. Every career on that Expo panel zigzagged. In dairy, that’s not failure—that’s how the strongest ones are built.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Unlock Peak Performance on Your Dairy Farm: Top Leadership Advice – Provides actionable strategies for building the “humble, hungry, and smart” team culture discussed by the panel. Learn specific communication and management techniques that help farm owners identify and retain character-driven talent in a competitive labor market.

- Women Shattering Dairy’s Glass Ceiling: Leadership, Innovation, and the Fight for Equality in 2025 – Expands on the success stories of Kylene Anderson and Amanda Lichtensteiger with hard data from the 2025 industry report. This strategic analysis reveals the shifting demographics of dairy leadership and how diverse management teams are driving higher profitability.

- Your 2025 Dairy Gameplan: Three Critical Areas Separating Profit from Loss – Shifts focus from career resilience to operational precision, detailing three technical adjustments to protect margins now. Discover how optimizing forage density, transition cow spacing, and methionine protocols can turn a volatile season into a profitable one.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.