Wisconsin’s first H5N1 case: healthy cow, full production, zero symptoms. Virus has already been spreading for 5 days. What farms with better outcomes did differently—and when they did it.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: The strategic issue: H5N1 spreads invisibly for five days before symptoms appear—by then, containment fails, and losses exceed $50,000 for average Wisconsin operations. Wisconsin’s December 14 confirmation in a symptom-free cow proves what California and Ohio demonstrated: detection infrastructure determines outcome, not traditional biosecurity. Activity monitoring systems flag rumination drops during that critical five-day window, catching the virus days before visual observation and potentially cutting outbreak costs in half. Wisconsin producers face three immediate decisions: confirm bulk tank surveillance status, assess the ROI of the monitoring system against outbreak risk, and implement enhanced parlor sanitization. Federal requirements are evolving toward mandatory testing and documentation—early adoption becomes strategic positioning, not reactive compliance. Market access will increasingly depend on cooperative-level biosecurity verification as processors prioritize supply-chain reliability over individual farm assurances.

The Dodge County confirmation changes the conversation for Wisconsin dairy. But here’s the thing—farms catching this early are managing it like any serious herd health challenge. Those catching it late are facing something that takes years to recover from. The difference comes down to detection, and that’s something every operation can address.

News broke earlier this morning that Wisconsin has its first confirmed H5N1 case in a dairy herd. If you’re reading this, you probably felt that same weight in your chest—the question of what it means for your operation, your neighbors, this industry we’ve all built our lives around.

But here’s what struck me as I dug into the details: the infected cow looked completely normal. She was found through pre-movement testing, not because anyone noticed something wrong. Eating fine. Producing fine. No fever, no obvious signs. The virus was replicating in her mammary tissue at levels high enough to trigger a positive, and without that surveillance protocol, nobody would’ve known for probably another week.

That detail matters more than the confirmation itself. It tells us something important about how this virus operates—and what we can actually do about it.

The Five-Day Window That Changes Everything

Anyone who’s managed fresh cows through the transition period knows how quickly things can shift. One day, everything looks fine; the next, you’re dealing with a displaced abomasum or a metabolic crash. You develop instincts for catching problems early.

H5N1 is testing those instincts in ways we haven’t seen before.

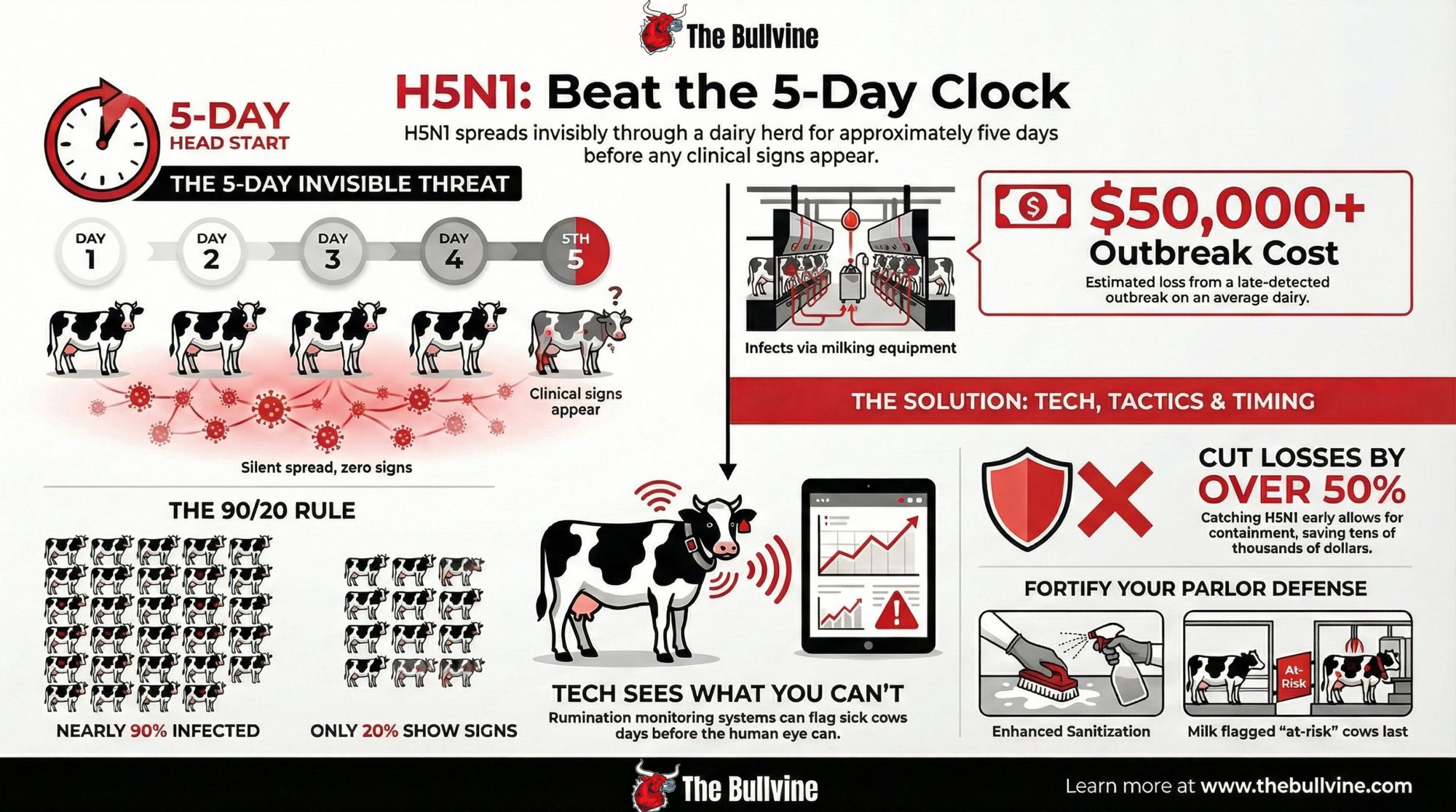

CIDRAP reported on a detailed study of an Ohio dairy outbreak that tracked exactly what happened as the virus moved through the herd. What researchers found was telling: rumination time and milk production started declining roughly five days before farm staff recognized clinical illness. The automated monitoring system caught what experienced dairy people couldn’t see during normal observation.

Think about what that means for your morning routine. You’re walking the pens, checking cows, looking for the usual signs. But this virus creates a window—about 5 days—during which infected animals look normal while the infection spreads through your parlor.

In that same Ohio investigation, clinical cases appeared about two weeks after apparently healthy cows arrived from Texas. When researchers ran serologic testing afterward, they found antibodies in nearly 90% of the 637 animals present during the outbreak phase.

Here’s the part that really got my attention: only about 20% ever showed obvious clinical signs.

Nine out of ten cows are potentially carrying the virus. Most never looked sick enough to flag. That’s a fundamentally different challenge than the mastitis cases and metabolic issues we’re used to managing.

The Economics That Frame Every Decision

A Wisconsin producer I spoke with last week put it simply: “I need to know what I’m actually risking before I can decide what to spend on prevention.”

Fair enough. Let’s walk through the numbers.

The CIDRAP report on that Ohio outbreak documented milk losses of roughly 900 kg per clinically affected cow—close to a ton—over about 60 days compared to herdmates that avoided clinical disease. Researchers estimated economic losses of around $950 per clinically affected animal, including milk, treatment, and an elevated culling risk.

For a herd around Wisconsin’s average size—somewhere in the low-to-mid 200s based on USDA numbers—proportionally scaling those results paints a sobering picture. A widespread outbreak affecting many animals could reach losses in the tens of thousands, potentially approaching six figures for larger operations. Earlier detection, limiting clinical cases to a smaller portion of the herd, could cut those direct losses by half or more.

That’s not a marginal difference. That’s the gap between a tough quarter and an 18-month recovery that affects every decision you make—breeding, culling, expansion plans, and whether your kids see a future in this operation.

What’s Actually Working

So what separates the farms navigating this with manageable losses from those facing crisis?

A veterinarian who’s worked through several outbreaks in other states told me the pattern is consistent: operations with detection infrastructure in place before the virus arrived fare dramatically better. Not because they prevent infection—that’s largely beyond anyone’s control—but because they catch it days earlier and contain its spread.

Dr. Jennifer Van Os at UW-Madison’s Department of Dairy Science has been making this point in her extension work. Activity monitoring systems, she notes, aren’t just about reproductive management anymore. They’re becoming essential for early disease detection—giving you a window into cow health that visual observation simply can’t provide.

The technology is familiar. SCR, Lely, Allflex—most of us have seen these systems, maybe considered them for heat detection or fresh cow management. A healthy cow ruminates 400-450 minutes daily. The systems establish individual baselines and flag when any animal drops more than 10% below her normal. That alert could reach you days before you’d notice anything wrong in the parlor.

Based on current vendor pricing, you’re looking at low-to-mid teens for a 200-250 cow operation, plus annual software fees. On a three-year equipment loan, that’s a few hundred dollars monthly.

Is that real money? Of course it is. But compare it to the figures for the Ohio outbreak. Earlier detection and limiting clinical cases could reduce losses by tens of thousands. The math isn’t complicated—it’s just uncomfortable because it means spending money you’d rather put elsewhere.

A central Wisconsin producer who installed rumination monitoring two years ago for reproductive management shared his perspective: “We justified it for heat detection. But when this H5N1 news started coming out of other states, I realized we had something more valuable than we’d planned for. We’re watching rumination data every morning now with different eyes.”

For financing, most Farm Credit associations offer equipment loans for this type of infrastructure. And I’m hearing some Wisconsin cooperatives are exploring member cost-share programs. Worth a conversation with your co-op leadership—they may be further along on this than you’d expect.

The Parlor: Where It Spreads, Where You Can Intervene

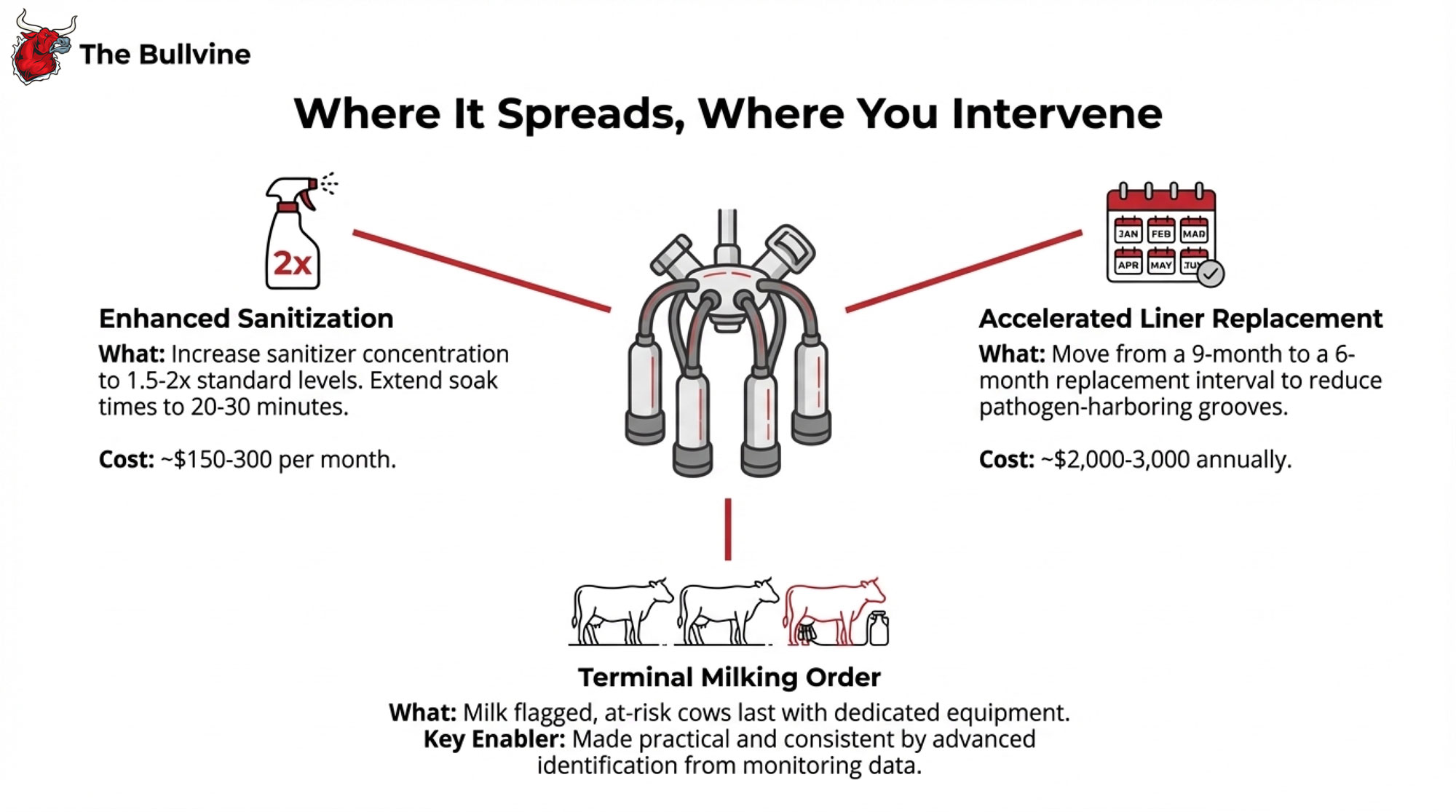

One thing the research has clarified: H5N1 in dairy cattle spreads primarily through contaminated milk and milking equipment. Not respiratory routes like poultry. The virus concentrates heavily in milk, and, as one PMC review explained, tainted milking equipment can infect cows because the milk contains such high viral loads.

Laboratory data show that H5N1 can remain infectious on equipment surfaces—such as stainless steel and rubber liners—for hours under typical dairy conditions. Those standard 12-15-minute CIP cycles we most of us run? They weren’t designed for this kind of viral persistence.

Here’s what operations are changing:

Enhanced sanitization. Sanitizer concentration up to 1.5-2x standard levels, soak times extended to 20-30 minutes. Additional chemical cost runs maybe $150-300 monthly. Real money, but manageable against outbreak costs.

Accelerated liner replacement. Moving from 9-month intervals to 6 months. Those microscopic grooves that develop with use can harbor pathogens even after sanitization. The cost differential is roughly $2,000- $ 3,000 annually.

Terminal milking order. This is where monitoring investment really pays off. When activity data flags animals with rumination drops, you mark those cows the night before, milk them last with dedicated equipment. Without advance identification, trying to implement sick-last protocols on the fly at 4:30 AM with a two-person crew… you know how that goes.

Dr. Pamela Ruegg at Michigan State made this point in a recent Dairy Cattle Reproduction Council webinar. The principles aren’t complicated—infected animals last, dedicated equipment, enhanced sanitation. The challenge is consistent implementation when you’re exhausted, and the cows keep coming. Technology that flags at-risk animals in advance makes those behavioral protocols actually achievable.

The Market Picture—Because It’s Not Just About Biology

Here’s where I want to be careful, because this part of the conversation can get heated.

Let me be absolutely clear about the science first: pasteurized milk is safe. FDA’s process engineering experts calculated that HTST pasteurization eliminates at least 12 log₁₀ EID₅₀ per milliliter—roughly a trillion virus particles. Their retail testing found all 297 sampled dairy products negative for viable H5N1. This isn’t speculation; it’s rigorous data.

But market behavior and food safety science operate on different tracks. That’s just reality.

Dr. Marin Bozic, the dairy economist at the University of Minnesota, has been tracking responses from buyers and processors. The conversation, he notes, isn’t really about whether milk is safe. It’s about supply chain risk management. When a region has confirmed cases, buyers start asking processors about contingency sources. Once those alternative relationships establish, they don’t automatically revert when the immediate situation resolves.

California’s recent experience illustrates the dynamic. In November 2024, milk production dropped 9.2%—Dairy Reporter called it the largest decrease in 20 years, amounting to around $400 million in lost revenue. Multiple sources confirm H5N1 affected more than 75% of California’s roughly 1,000 dairy farms.

Yet retail prices stayed relatively flat. Consumer demand continued normally. What happened was internal reallocation—processors shifted milk among channels. The milk flowed, but differently. Farm-level payments felt the pressure even as retail markets showed no disruption.

The federal response has included over $230 million in Emergency Assistance for Livestock program funds to California producers.

For Wisconsin operations, the implication is that biosecurity investment isn’t purely about production losses—it’s also market positioning. Over time, processors may increasingly favor farms demonstrating strong disease-risk management. The specific structures are still emerging, but the direction seems clear enough to factor into planning.

I recognize this adds burden to operations already managing tight margins. That frustration is legitimate. But understanding the dynamics beats being surprised by them.

What’s Coming From Madison and Washington

Dr. Keith Poulsen, directing the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, has been coordinating with DATCP on response protocols. As he told Brownfield Ag News, the lab has been preparing for expanded milk testing capacity.

Since April 2024, according to AVMA, a federal order has required testing lactating dairy cattle for H5N1 before interstate movement. December 2024 brought USDA’s new federal order launching the National Milk Testing Strategy.

The direction is clear: systematic testing, documentation requirements, and eventual biosecurity verification of some kind. Exact timelines remain fluid—I want to be honest about that uncertainty—but the trajectory is consistent enough that planning makes sense.

Kevin Krentz at Wisconsin Farm Bureau has been pushing for producer input on developing frameworks. His point resonates: members need transparency on what’s coming and adequate lead time for investment decisions. Regulatory requirements arriving with a 30-day notice put farms in impossible positions.

Staying engaged with cooperative leadership and industry organizations matters right now. The decisions made in the next six months will shape requirements for years to come.

This Week: What Actually Needs to Happen

Let me get specific, because general advice doesn’t milk cows or pay bills.

Monday-Tuesday: Confirm surveillance status. Call—don’t email—your cooperative’s milk quality director. Verify how your farm connects to the current bulk tank testing. Many producers assume enrollment is automatic. Often it isn’t. If your cooperative can’t provide clear information, contact the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory through UW-Madison’s School of Veterinary Medicine.

Tuesday-Wednesday: Start the monitoring conversation. Contact SCR, Lely, or Allflex for quotes and installation timelines. Be direct about being in a state with confirmed H5N1 and needing installation promptly. Slots are filling. If financing is a concern, contact your Farm Credit office about equipment options.

Wednesday-Thursday: Schedule a veterinary consultation. Book a 90-minute on-farm meeting explicitly focused on H5N1 protocol review. Bring your milking routine documentation, CIP specifications, and recent herd health records. Your vet can help design terminal milking protocols realistic for your parlor configuration and staffing.

Friday onward: Implement and document. Enhanced CIP protocols can go live immediately—sanitizer and timing changes don’t require equipment purchases. Post new protocols in your parlor. Train staff on H5N1 milk quality indicators. Document everything; future requirements will ask for implementation dates.

This represents real time and money during an already demanding season. But discovering H5N1 through a clinical outbreak when much of your herd is already affected means substantially higher losses. The investment provides early warning, making the cost difference possible.

For Conversations With Your Lender or Insurance Agent

If you’re financing biosecurity investments or reviewing coverage, here’s the key point: based on Ohio herd research, earlier detection can limit clinical cases and reduce outbreak losses by tens of thousands of dollars. Monitoring investment has clear payoff potential through single-outbreak mitigation.

Ask your insurance agent whether livestock mortality policies have disease exclusions affecting H5N1 claims, and whether biosecurity investments could affect premiums. Review farm credit covenants for provisions triggered by herd health events—better to understand now than during a crisis. USDA has been discussing potential H5N1 indemnity programs similar to those for poultry, though nothing has been finalized.

The Longer View

Is this temporary—something we’ll manage and move past? Or is something more fundamental shifting?

Probably somewhere between, but leaning toward structural change.

H5N1 itself will eventually become more manageable. Every disease challenge in dairy history has followed that arc—better tools, refined protocols, accumulated experience. Five years from now, we’ll handle this differently than today.

But the infrastructure being built now—the testing requirements, the documentation expectations, the market preference for verified biosecurity—that’s not disappearing when H5N1 becomes routine. California showed how quickly and widely this can move through a dairy region. Other areas will likely face similar challenges.

What H5N1 is really doing is accelerating something already underway. Commodity production competing purely on efficiency is gradually giving way to verified, documented, risk-managed production. That shift was happening slowly; this is speeding it up.

For Wisconsin, that creates both challenge and opportunity. The cooperative infrastructure, the research institutions, the dairy heritage—these are genuine assets that could position Wisconsin well. But capturing that advantage requires coordinated investment. Individual farms operating at thin margins can’t do it alone.

The cooperatives that begin pooling resources—member monitoring systems, collective protocols, market positioning—will give their members a path forward. Those treating this as temporary may find their members facing disadvantages that persist long after the immediate crisis fades.

Wisconsin has been losing hundreds of dairy operations annually. Margins remain tight for many family farms even in good years. H5N1 doesn’t fundamentally change that pressure—but it adds another factor making proactive positioning more important.

The Bottom Line

The detection gap is real. Five days of invisible spread precede clinical signs. That window determines whether you’re managing a challenge or surviving a crisis.

The tools to close that gap exist. They cost money. They require changes to routines that have worked for years. But the economics—verified by research from operations that have been through this—support the investment.

The market and regulatory environment is shifting toward verified biosecurity. You can position ahead of that shift or react to it. Positioning costs less.

None of this is easy. None of it is fair to operations already stretched thin. But understanding the situation clearly is the first step toward successfully navigating it.

Wisconsin dairy has faced challenges before and adapted. This one requires faster adaptation than most—but the resources exist, the knowledge is available, and the path forward is clearer than it might feel in this particular moment.

Key Takeaways

- Detection timing shapes outcomes. Ohio herd research shows changes begin roughly five days before clinical recognition. Operations with monitoring catch outbreaks earlier. The financial difference reaches tens of thousands of dollars.

- Investment sequence matters. Detection capability first. Parlor protocols second. Traditional biosecurity third. Many operations reverse this, spending on visible measures while lacking systems that determine outbreak severity.

- Market dynamics and food safety are different conversations. Pasteurized milk is definitively safe—FDA research establishes large safety margins. But buyer supply-chain confidence drives market decisions. Documented biosecurity may bring preferential treatment.

- Regulatory direction is set; timing remains fluid. Expanded testing, documentation, and biosecurity verification are developing. Exact schedules remain unclear, but direction is consistent enough that proactive preparation makes sense.

- Structural change is real but manageable. H5N1 accelerates the transition toward verified production. Wisconsin’s cooperative infrastructure could position the state well—with coordinated investment rather than fragmented response.

The Bullvine will continue tracking H5N1 developments as this situation evolves. We’re particularly interested in hearing from producers implementing these measures—your experiences will inform our coverage and help others navigate these decisions. Share your story through our website or connect with us on social media.

For Wisconsin-specific resources, contact the UW-Madison Division of Extension Dairy Program or the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at the UW-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine. For national H5N1 dairy updates, USDA APHIS maintains current information at aphis.usda.gov.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- US Dairy Farmers’ Guide: Navigating Bird Flu Outbreak – Provides a tactical breakdown of permit requirements, quarantine protocols, and federal compliance standards essential for keeping milk trucks moving during active outbreak restrictions. This guide translates regulatory complexity into a clear operational checklist for farm managers.

- How Canada Keeps Its Dairy Cows Free from Bird Flu – Examines the specific national biosecurity strategies and border protocols that have protected Canadian herds. Offers a valuable strategic benchmark for US producers looking to upgrade their own lines of separation and visitor entry protocols beyond standard requirements.

- Exploring Dairy Farm Technology: Are Cow Monitoring Systems a Worthwhile Investment? – Delivers a detailed ROI analysis of activity and rumination monitoring systems, moving beyond the hype to evaluate payback periods. Essential reading for producers calculating the financial feasibility of the detection infrastructure recommended in the main article.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!