63% of U.S. milk now comes from 1,000+ cow operations. For mid-sized farms, the next 18 months are about turning assets into options—before you’re forced to.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Mid-sized dairy operations (300-2,000 cows) are caught in an efficiency trap: simultaneous productivity gains across all regions create oversupply that compresses margins despite record component levels. With 2,500-2,800 farms exiting annually and federal policy favoring consolidation over direct payments, the next 18 months represent a critical decision window. Four pathways remain strategically viable: Chapter 12 debt restructuring, strategic sale before distress, value-added market pivots, or separating herd sale from land retention. High-genomic herds offer crucial advantages—GTPI 2,800+ animals command $2,500-4,000 per head versus $1,500-2,000 for commercial genetics, representing $600,000-1.2 million in additional equity for a 600-cow operation. Decision factors include geography (Southwest water constraints, Upper Midwest cooperative dynamics), debt-to-asset ratios (above 60% signals restructuring need), and family goals around land preservation versus operational continuity. Success five years from now won’t mean staying largest or most efficient—it will mean acting strategically while equity exists, rather than being forced into distressed decisions after losses erase options.

Look, something is happening in dairy right now that we need to talk about honestly. If you’re running anywhere from 300 to 2,000 cows, you’re feeling it every time you look at your milk check. Margins that were tight 18 months ago? They’ve gotten tighter. Markets that looked uncertain coming into this year? Still haven’t cleared up. And meanwhile, the whole structure of the industry keeps shifting underneath us—new processing plants going up, big cooperatives talking expansion, federal support flowing to row crops while dairy operates in a fundamentally different policy environment.

What I’ve been tracking over the past year—and what keeps coming back in conversations with producers from Wisconsin to California, lenders across the Midwest, and Extension folks in multiple regions—is that this isn’t just another rough patch we need to weather. It’s something more fundamental. We’re watching a full-scale experiment on whether U.S. dairy can consolidate faster than its physical and financial constraints catch up. And mid-sized family operations are right in the middle of that experiment, whether we signed up for it or not.

Here’s what matters most: understanding what’s happening systemically doesn’t change the fact that you might be losing real money every month. But it does change how you think about the decisions you face over the next 18 months. Because that window? It matters more than most people realize right now.

So let’s walk through three questions: What system are we actually operating in? Who’s positioned to benefit from how things are currently structured? And most importantly—what real options do mid-sized operations have before that 18-month window closes?

How We Got Here: The Policy Shift Nobody’s Talking About

Federal agricultural support policy over the past few years has increasingly emphasized assistance for row crop growers dealing with trade disruptions and tariff impacts. Dairy has received proportionally less direct relief, with policy focus shifting toward what Washington calls “structural solutions”—market access improvements, processing investments, labor reform.

And you know what? This wasn’t entirely surprising if you’d been watching the patterns develop.

The 2018-2019 Market Facilitation Program showed us how this plays out. Eric Belasco and his colleagues at Montana State published research in Food Policy that found payments were concentrated on larger farms receiving higher per-acre payments, even when the formulas appeared neutral on paper. The Government Accountability Office documented in their September 2020 report GAO-20-563 that less than 10 percent of those payments went to farms producing specialty crops, dairy, or hogs—despite these sectors representing significant chunks of the farm economy.

But here’s what really caught everyone’s attention, and it’s worth understanding because it shaped how policymakers think about farm support now. Jason Hancock at The Missouri Independent documented in January 2023 how giant fertilizer companies hauled in hundreds of millions in net earnings right after those payments went out. One major producer saw earnings jump more than 1,000% in the first nine months of 2022. Farmers were spending nearly four out of every ten dollars of corn production costs on fertilizer.

I remember reading Tim Dufault’s testimony to the House Ways and Means Committee back in September 2020. He’s a wheat and soy farmer from Polk County, Minnesota, and he put it plainly: “While we are being paid not to sell to one of the fastest growing markets in the world, our competitors are filling the void. Our loss is Canada, Brazil, Russia, and Australia’s gain. In the past two years, Canada’s wheat exports to China have increased 400% while ours have fallen.”

So policymakers saw all this—the concentration effects, the value capture by input suppliers, the competitive losses—and you can understand why there’s now a different view in Washington. There’s a growing sense that big, one-time relief checks don’t fundamentally fix structural issues. They might soften the blow short-term, but they can also delay necessary adjustments, disproportionately strengthen the largest operations, and leave producers more leveraged when the next downturn hits.

The strategy shifted toward processing investment incentives, trade access efforts, stronger labor policy, and pricing reforms. From a policy perspective, the bet is that if the system’s infrastructure and markets get “right-sized,” profitability will eventually follow. Whether that’s the right bet or not—well, we’re living through that experiment right now.

For a mid-sized farm losing serious money each month? That’s a very slow boat to wait for.

The Consolidation Numbers: What the Data Actually Shows

The numbers tell a clear story if you’re willing to look at them honestly, and I think it’s important to separate what we know from what we’re still figuring out.

USDA’s 2022 Agricultural Census came out in early 2024 and confirmed what most of us already felt: the continued acceleration of the decades-long consolidation trend. Operations with more than 1,000 cows now produce roughly 63% of U.S. milk. The total number of dairy farms continues declining—about 2,500 to 2,800 operations exiting annually in recent years, according to USDA NASS data. That’s roughly seven farms disappearing each day, every day.

And here’s what’s particularly interesting from a production standpoint: USDA’s 2024 dairy outlook projected modest milk production growth continuing, with total production expected to remain above 226 billion pounds. That growth comes from both modest herd expansion and productivity gains. Per-cow production keeps climbing—better genetics, precision feeding, improved management across the board.

Component levels have hit historic highs, too. USDA Dairy Market News documented through 2024 that butterfat tests were reaching above 4.3% and protein pushing past 3.3%. These are multi-decade peaks in milk quality. Total milk solids are up even as volume growth stays more modest.

On paper, that looks like the efficiency story everyone talks about, right? More output from fewer cows and fewer farms should mean lower costs and better margins. That’s the theory.

But the margin story hasn’t followed that script, and this is where it gets complicated. University of Wisconsin Extension data documented compressed milk-over-feed margins through 2024. I’ve talked with producers from Michigan to New York who reported some of their tightest margins in years. Farm Bureau analysis through 2024 noted that despite strong component production, dairy producers were navigating compressed margins, with milk prices failing to keep pace with elevated feed, labor, and compliance costs.

What’s creating the squeeze is something bigger than any individual farm’s decisions—it’s simultaneous production growth across all major exporting regions. Recent global dairy market analysis has documented this unusual pattern: milk output growing in the U.S., EU, New Zealand, and South America all at the same time. Typically, at least one part of the world is dealing with some limiting factor—weather, disease, margins, something—that reduces milk growth. Not this time. Everyone’s pedal is down at once.

“When everyone increases efficiency simultaneously without matching demand growth, you get what agricultural economists call an ‘efficiency trap.’ Each farm individually makes rational decisions—better genetics, improved feeding, automation. But collectively, the industry ends up with more high-quality milk than global markets can absorb at profitable prices.”

This was clearly evident in Global Dairy Trade auction results through late 2024: prices fell as milk supply outpaced demand.

That’s the environment mid-sized farms are navigating right now. Not because anyone did anything wrong—because everyone did what made sense individually.

Processing Investments: Opportunity or Lock-In?

Layered on top of consolidation is a significant wave of new processing construction, and I think this deserves careful attention because it’s shaping market access in ways that aren’t immediately obvious.

Industry estimates point to seven to eleven billion dollars in new dairy processing investments announced or underway across multiple states, with completion timelines running through 2028. That’s a massive amount of capital flowing into the sector.

On one hand, this represents real confidence in dairy’s long-term prospects. More capacity can mean new products, better export-oriented manufacturing, and improved balancing for regions with seasonally heavy production. I’ve talked with producers near some of these new facilities who see a genuine opportunity to access premium markets they couldn’t reach before.

| Herd Size | Avg Annual Profit per Cow | Cost of Production | Debt-to-Asset Ratio | Exit Rate (Annual) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small (Under 250) | $200-$400 | $22-$24/cwt | 25-35% | 2-3% |

| Mid-Size (300-2,000) | -$100 to $600 | $19-$22/cwt | 40-60% | 5-7% |

| Large (2,000+) | $800-$1,200 | $16-$18/cwt | 30-45% | <1% |

On the other hand—and here’s where it gets complicated for mid-sized operations—these plants come with minimum-volume requirements that shape which farms can participate profitably. Hoard’s Dairyman noted back in August 2021 that modern processing facilities operate most efficiently at high throughput rates. A plant designed to run four to five million pounds per day doesn’t pencil well at 40 or 60 percent capacity utilization. The economics simply don’t work.

That reality pushes facilities to secure milk from large, consistent suppliers—typically very large herds or tightly aligned cooperative members. Companies aren’t investing hundreds of millions in new plants and then wondering where they’ll get the milk from. Most locked in future milk supply commitments before construction even started. If you weren’t part of those early conversations, you might find yourself on the outside looking in when the plant fires up.

This creates both opportunity and constraint, depending on where you sit. If you’re a mid-sized farm near new capacity and you can scale up or partner effectively, there may be room to grow into those supply relationships. But if you’re in a less favored location, or can’t meet the volume consistency these plants need, you might find premium markets or long-term contracts harder to secure than they were five years ago.

There’s also a timing risk worth thinking about, and I say this recognizing we don’t have perfect foresight here. If global demand stays soft—if China doesn’t significantly increase imports, if domestic consumption grows slowly—the industry could reach a point in a few years where there’s more processing capacity in the ground than profitable milk to run through it.

We’ve seen this scenario play out elsewhere. Industry observers in Ireland have documented chronic underutilization challenges in their dairy processing sector. All the capacity is needed for only a few peak weeks during the year. The rest of the time, plants run well below optimum levels, with some facilities even shutting down during quieter winter months. Whether we’re headed for something similar here remains to be seen, but the risk is real enough to factor into your planning.

From a farm-gate perspective, this creates a double bind. Short-term, plants need milk to fill capacity—that can feel like an opportunity if you’re positioned right. But long-term, if enough mid-sized operations exit and prices don’t recover, the system may find itself with stranded investment, fewer independent producers, and greater dependence on highly leveraged mega-dairies.

Understanding the Incentive Structure

It’s worth taking a calm look at who’s structurally aligned with consolidation and these processing investments. This isn’t about pointing fingers or assigning blame—it’s about understanding incentives so you can make better decisions for your own operation. Because when you understand the incentives, the patterns start making more sense.

Large cooperatives and integrated processors sit in an interesting position. When an organization both aggregates milk from member farms and owns processing plants, it effectively participates on both sides of the transaction. Take DFA as an example—according to their annual disclosures and public filings, they control roughly 30% of U.S. milk production while operating 44 processing facilities they’ve acquired over the years, including that $433 million Dean Foods asset purchase back in 2020.

DFA’s leadership has been pretty direct in its industry communications about the need for consolidation to maintain competitive positioning in today’s market. And from their perspective, you can see why. When farms consolidate, and more milk flows through fewer, larger plants, these integrated organizations gain scale efficiencies, widen their influence over pricing and contracts, and strengthen their position with retailers and export buyers. If you’re running a cooperative with processing assets, consolidation makes a lot of business sense.

Input suppliers and technology providers also benefit from the capital requirements. Moving from 500 to 2,000 cows, or from 2,000 to 5,000, typically requires a significant investment in genetics programs, robotic systems, precision feeding, and health-monitoring technologies. These sectors tend to capture a meaningful portion of any cash that flows into the system, whether from stronger prices or government programs. We saw that pattern documented pretty clearly after the 2018-2019 MFP program, and there’s no reason to think it would be different next time.

| Asset Category | Investment Range | Monthly ROI | Payback Period | 18-Month Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beef-on-Dairy Program | $50-$120/cow | +$35-$55/cow | 2-3 months | CRITICAL |

| Herd Genetics (GTPI 2,800+) | $150-$300/cow | +$25-$45/cow | 6-8 months | CRITICAL |

| Debt Consolidation | Varies | +$180-$450/cow | Immediate | CRITICAL if >60% D/A |

| Milking System Upgrades | $2,500-$4,000/cow | +$60-$90/cow | 36-48 months | HIGH |

| Feed Efficiency Tech | $80K-$150K total | +$15-$30/cow | 18-24 months | MEDIUM |

Financial institutions and land investors have also found opportunities in the transition. Agricultural economists have documented how, as mid-sized family farms struggle, farmland and facilities often change hands—sometimes to neighboring farms looking to expand, sometimes to outside investors who then lease land back to operators. Over time, this can separate land ownership from day-to-day farm control, shifting more value toward outside capital.

Federal Reserve agricultural credit surveys through 2024—particularly from the Chicago and Kansas City districts, which cover major dairy regions—showed farmland values holding relatively stable but with notable variation. Quality dairy farmland in growth regions maintained strong values, while more marginal dairy land in areas experiencing significant farm exits saw softer demand. The market’s making distinctions now that it didn’t make ten years ago.

None of this suggests these players are acting maliciously or even unethically. They’re responding to the same market signals and economic pressures as farmers—looking for growth, efficiency, and risk management. But it does matter for you to understand that the system isn’t automatically set up to protect or preserve mid-sized, family-owned, commodity-oriented dairies. That’s not the system’s design, and recognizing that fact is the first step toward making better decisions.

The default path—continue as is and wait for a better year—assumes the system wants you to succeed in your current form. The evidence suggests otherwise.

Geography Shapes Your Options More Than You’d Think

Before we get into specific strategic paths, here’s something that often gets glossed over in national conversations about dairy consolidation: your location matters enormously. What makes sense in one region might be completely impractical in another.

In the Southwest—Texas, New Mexico, Arizona—consolidation has gone furthest. Large operations dominate, feeding relies heavily on irrigated crops, and water availability is becoming the limiting constraint. Dairy Herd noted last November that optimism about Texas dairy’s growth potential comes with a significant caveat: USGS data shows the Ogallala Aquifer dropping by 2 to 3 feet annually in stressed areas, and NOAA climate data confirms the Panhandle receives only 12 to 18 inches of rain per year.

A producer I talked with last month near Muleshoe runs 4,500 cows and has been farming that same ground for three generations. He’s watching his wells drop year after year. “We’ve got maybe 15, 20 years at current draw rates,” he told me. “After that, we’re either drilling deeper—if there’s anything left to drill to—or we’re done.” That reality is shaping every expansion decision, every equipment purchase, every long-term plan. It’s not an abstract policy discussion. It’s water levels measured in feet per year.

In the Upper Midwest—Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan—cooperative density and processing capacity create different dynamics. Proximity to multiple buyers can provide negotiating leverage that farms in more isolated regions don’t have. But relationships matter here, and they can shift. That 2017 situation when DFA terminated marketing for 225 independent producers in the Midwest—documented in Farm and Dairy that May—reminded everyone that cooperative relationships aren’t permanent fixtures. Market access you have today isn’t guaranteed tomorrow.

In the Northeast—New York, Pennsylvania, Vermont—seasonal production patterns, smaller average farm sizes, and closer proximity to fluid milk markets create distinct opportunities and constraints. Organic and grass-based systems are more common here, partly because of climate and topography, but also because direct-to-consumer markets are more accessible when you’re within a couple of hours of major population centers. I’ve seen mid-sized operations in this region successfully transition to grass-based organic production in ways that simply wouldn’t work in the Southwest or upper Plains.

In the Southeast—Georgia, Florida, Tennessee—operations often work in hot, humid conditions that require different facility designs and management approaches. Heat stress management becomes a year-round consideration, not just a summer challenge. But population growth in regional markets can create local market opportunities that export-oriented regions don’t have. A 600-cow operation I know outside Atlanta pivoted three years ago to supplying local schools and restaurants with bottled milk. They’re capturing $5 to $7 per gallon at retail, versus $3.50 to $4 for commodity milk. It requires handling, processing, distribution, and compliance with food safety standards—a completely different business model. But proximity to that growing metro market made it viable in ways it wouldn’t be for an operation in rural Kansas.

The point isn’t to map every regional difference—it’s to recognize that a strategic decision framework that works for a 1,000-cow operation in west Texas might not make sense for a 400-cow farm in central Wisconsin or a 600-cow operation in upstate New York. As you read through what’s ahead, filter it through your regional context, market access, climate constraints, and local land values.

Why the Next 18 Months Matter So Much

Most mid-sized producers I’ve talked to over the past year find themselves in a similar spot. Margins are negative or barely breakeven. Debt levels are uncomfortable but not catastrophic yet. Land still holds meaningful equity. And everyone—kids, employees, lenders—is looking for clarity about the farm’s future.

The 18-month horizon that keeps coming up in conversations isn’t a promise of recovery. It’s better understood as a decision window—long enough to execute a major transition, but short enough that passive waiting can quickly eat through remaining equity or liquidity. And I want to be careful here because I’m not predicting what will happen in 18 months. What I am saying is that waiting 18 months to start making decisions could leave you with significantly fewer options than you have today.

“What producers are discovering is that the most important asset in 2026 and 2027 may not be cows or equipment—it’s flexibility.”

The operations that keep options open, preserve capital, and move deliberately will be in a much better position to react when the longer-term shape of the industry becomes clearer.

Here’s why timing matters: by mid-to-late 2027, several things will likely be clearer than they are today.

We’ll know whether those processing investments we talked about are filling up with committed supply or struggling to source milk. We’ll have a better sense of whether China reopens meaningfully as an export market or continues favoring New Zealand and EU suppliers. We’ll understand whether water constraints in the Southwest are manageable or becoming acute enough to force consolidation there, slowing or reversing them. We’ll see whether mega-dairy expansion continues at current rates or runs into financial constraints as debt service becomes more challenging in a compressed margin environment.

If you’re still in decision mode in late 2027—still trying to figure out your direction—your options narrow considerably. Land markets may have softened if there’s been a wave of distressed exits. Bankruptcy courts may be backlogged if many farms hit crisis simultaneously, which means the relief that tool can provide becomes slower and less predictable. Buyers looking to expand may already have their supply commitments locked in with those new processing facilities, so they’re not actively seeking additional milk or land.

But if you move thoughtfully in 2026 and early 2027, you position yourself with capital and options to make choices based on what actually unfolds, rather than being forced into whatever’s left available. That’s the fundamental difference between proactive and reactive decision-making in this environment.

Four Strategic Paths Worth Serious Consideration

Every farm’s situation is different, but in conversations with lenders, advisors, and producers across multiple regions, four broad strategies keep emerging for operations in that 300 to 2,000 cow range. None of them are easy. All involve tradeoffs. All require difficult family conversations. But each one can preserve options better than passively continuing operations at monthly losses.

1. Structured Debt Relief: Using Chapter 12 Strategically

Chapter 12 bankruptcy is a specialized form of reorganization explicitly designed for family farms. It’s not liquidation by default—it’s a legal tool to restructure terms with creditors, reduce overall debt loads in some cases, and continue operating under court-supervised plans that give you breathing room to get back to profitability.

And it’s being used more. Agricultural finance professionals and court observers have noted increased Chapter 12 bankruptcy activity among dairy operations over the past year or so. What’s particularly noteworthy is that producers who use this tool strategically—before crisis forces their hand—have been able to preserve substantial capital—often in the six-figure range—that would otherwise have been lost to creditors in unmanaged default situations.

I recently spoke with a producer in Wisconsin who filed Chapter 12 about 18 months ago. His debt-to-revenue ratio had climbed above 75%, he was burning through equity every month, but the underlying operation was productive and could have been viable with a cleaner balance sheet. Chapter 12 allowed him to restructure payment terms, reduce some debt principal through negotiations with secured creditors, and continue operating. He’s not out of the woods yet, but he’s got a path forward that didn’t exist before filing.

This option warrants serious consideration if your debt-to-revenue ratio is high—say, above 60 or 70 percent—your liquidity is tight, but you genuinely believe the underlying operation is productive and could be viable with a cleaner balance sheet. That last part is critical. Chapter 12 doesn’t fix a structurally unprofitable operation. It fixes an operation that’s temporarily struggling under a debt load accumulated during better times or from expansion decisions that didn’t work out as planned.

What it requires: good legal and financial advice from professionals who specialize in agricultural bankruptcy, honest and conservative projections about future profitability (courts don’t accept optimistic fairy tales), and willingness to work through court processes that can feel invasive and uncomfortable. There are tax implications, too—canceled debt can create taxable income that you need to plan for. But for farms where the alternative is losing the operation entirely, those are manageable problems.

The timing piece matters here, too, and this is something your attorney will likely emphasize. Bankruptcy courts are currently processing dairy cases relatively quickly. If the number of filings continues to accelerate—and there’s reason to think it might—processing times could lengthen significantly. Filing while courts still have capacity, and while you have equity to protect, gives you better leverage in negotiations with creditors than waiting until crisis forces your hand and your equity is already gone.

| Metric | Chapter 12 | Consolidation/Direct Payment | Strategic Sale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk Price Breakeven | $18.50/cwt | $20.50/cwt | N/A |

| Monthly Cash Flow Impact | +$15,000-$25,000 | -$5,000 to +$5,000 | N/A – exited |

| Feed Cost Sensitivity Buffer | Moderate – 30% | High Risk – 10% | N/A |

| Equity After 5 Years | 55-65% | 30-40% | 70-80% recovered |

2. Strategic Sale While Equity Still Exists

For other operations—especially where land is highly valuable, family members aren’t committed to long-term dairy, or facilities would require major capital investment to stay competitive—a deliberate sale before the operation becomes distressed can preserve far more value than waiting.

According to USDA NASS Land Values data and Federal Reserve agricultural surveys through 2024, quality dairy farmland was holding value relatively well, with Midwest dairy ground in the $6,000 to $8,000 per acre rangedepending on location and quality. But there was an important variation that matters for your planning. Prime farmland in areas with strong demand—near growing processing capacity, in regions with good water, in counties experiencing population growth—saw stable or slightly rising values. More marginal dairy land in areas experiencing significant farm exits saw softer pricing. The market’s making distinctions.

The key insight here is separating the decision about the operating dairy from the decision about the underlying land asset. They’re related, obviously, but they’re not the same decision. Sometimes the best move is to market the farm to buyers who want to expand, want the land for cropping, or might be willing to lease facilities back to you for a transition period.

Structure the sale to convert equity into cash for debt repayment, retirement planning, or next-generation flexibility. Consider sale-leaseback arrangements that let you convert equity to cash, continue farming for a period as tenants while you transition to other work or activities, and maintain some connection to the land and community.

Let me give you a hypothetical example that mirrors situations I’ve seen recently:

Say you’re running 600 cows on 500 acres. Your land is worth $7,500 per acre in the current market—that’s $3.75 million. Buildings and equipment might bring $800,000 to $1.2 million, depending on condition, age, and how well you’ve maintained them.

Here’s where your herd genetics matter more than many producers realize. If you’re running 600 cows with strong genomic profiles—animals averaging GTPI above 2,800 or genomic NM$ above $1,000—you’re sitting on a significantly more liquid and valuable asset than a commercial herd at similar production levels. Council on Dairy Cattle Breeding data shows that high-genomic animals consistently command premiums in dispersal sales, often bringing $2,500 to $4,000 per head to breeders and operations looking to upgrade genetics quickly. That’s compared to $1,500 to $2,000 for quality-producing cows without distinguished genetic merit.

| Breeding Strategy | Initial Investment | Component Increase (12mo) | Revenue Impact (18mo) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-GTPI Elite (2,800+) | $85/cow | 4.5% | $280/cow |

| Commercial Genomic Bulls | $45/cow | 2.8% | $150/cow |

| Conventional Breeding | $25/cow | 1.2% | $60/cow |

For a 600-cow herd, that genetic premium can represent an additional $600,000 to $1.2 million in sale value—a substantial difference when you’re trying to preserve equity. I’ve seen operations with high-genomic herds market animals through private treaty sales to multiple buyers seeking specific genetic lines, often achieving better prices than auction or wholesale dispersal would.

Total asset value in our example sits around $4.5 to 5 million, potentially reaching $5.5 to 6 million with a high-genomic herd. If your debt sits at $4 million, you’ve got roughly $550,000 to $950,000 in remaining equity with an average herd, or potentially $1.5 to $2 million with superior genetics.

A strategic sale now, while that equity still exists and before you’ve been in financial distress, could let you pay off debt completely, walk away with substantial liquid capital, potentially lease back the operation for two to three years to generate transition income while you figure out next steps, and position younger family members to make their own choices without the burden of an underwater dairy operation hanging over them.

Now compare that outcome to continuing operations at, say, $20,000 per month losses. Six months erodes $120,000 from that equity cushion. A year takes $240,000. Within 18 to 24 months, the equity buffer is gone, and you’re in crisis mode with far fewer options. The sale happens anyway, but now it’s distressed, rushed, and buyers know you’re desperate. The price reflects that reality. And if you’ve got high-genomic animals, distressed sales rarely capture their full genetic value—you’re more likely to get commercial pricing when you’re forced to move quickly.

This is emotionally difficult—I’m not minimizing that at all. Nobody goes into dairy planning to sell. But for some families, it’s the path that best balances debt repayment, retirement security for an older generation, and flexibility for the next generation to find their own path in agriculture or elsewhere.

3. Pivoting to Niche Markets and Value-Added Production

A smaller but growing set of operations are taking a different route: stepping off the commodity treadmill altogether and finding ways to capture more value per unit of milk produced. This builds on what we’ve seen in specialty agriculture for decades—differentiation creates pricing power.

Farms pursuing this route are considering several approaches, and what works depends heavily on location, family interests, and market access.

Organic or grass-fed milk contracts can command premiums of 30 to 60 percent over conventional commodity milk. I know of a 250-cow operation in Vermont that transitioned to certified organic, grass-fed production in 2021. They invested 18 months in the three-year certification process while managing the transition, adjusted their feeding program and grazing systems, and now capture an $ 8-per-hundredweight premium over conventional pricing. That premium more than covers their lower per-cow production and the additional management complexity. For them, producing 16,000 pounds per cow annually at a premium beats producing 22,000 pounds at commodity pricing.

But the transition takes time and commitment. You’ve got that three-year organic certification process. You’re changing your feeding program, your management systems, and possibly your facilities. And the organic milk market has had its own challenges with supply-demand imbalances in recent years, so you can’t assume premium pricing will last forever. Do your homework on current market conditions before making this leap.

On-farm processing for cheese, yogurt, or bottled milk offers even higher potential margins, but it comes with substantially higher complexity. Here’s the basic math from dairy science: roughly ten pounds of milk yields one pound of cheese. So 50,000 pounds of milk converted to cheese gives you about 5,000 pounds of finished product. At $4 to $6 per pound retail, that’s $20,000 to $30,000 in gross revenue versus maybe $8,000 to $9,000 if sold as fluid milk at current commodity pricing.

But—and this is a big but—you’re adding processing costs, labor, marketing expenses, regulatory compliance, food safety systems, and all the complexity of becoming a food manufacturer and retailer rather than just a milk producer. I’ve seen operations do this successfully, but they’re almost always near population centers, they’ve got family members genuinely energized by the business-building aspects, and they’re willing to invest two to three years getting established before the economics really work.

Agritourism, farm experiences, and educational programs represent another revenue stream that some operations near population centers are tapping into. I know of farms generating $50,000 to $150,000 annually from farm stays, tours, farm-to-table events, and educational programming. This typically pairs with a smaller herd—100 to 300 cows—but creates real revenue diversification that helps during commodity market downturns.

Renewable energy side income from biogas digesters, solar installations, or wind easements can add $50,000 to $200,000 annually once installed. But they require significant upfront capital—often $200,000 to $500,000—and you’re banking on energy prices, incentive programs, and utility contracts staying favorable for 15 to 20 years to justify the investment.

The common thread across all these approaches: reduce or stabilize herd size, shift focus from volume to margin per unit, and invest heavily in marketing, relationships, and brand rather than just production facilities. You’re becoming a different type of business than a commodity dairy farm.

| Year | Small Herds | Mid-Size (300-2,000) | Large Herds (2,000+) | Profit Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | $350 | $420 | $950 | $530 |

| 2025 | $280 | $380 | $1,020 | $640 |

| 2026 | $220 | $290 | $1,080 | $790 |

| 2028 | $150 | $180 | $1,180 | $1,000 |

| 2030 | $100 | $110 | $1,280 | $1,170 |

This route makes the most sense when you’re near a population center, when one or more family members are genuinely interested in entrepreneurship and direct sales rather than just dairy production, and when your balance sheet can support a 2- to 3-year transition in which cash flow stays tight while you build market presence and customer relationships.

It’s not a quick fix—most successful transitions take two to three years of careful planning and execution. But for operations with the right location, family interest, and financial runway, it’s been a way to stay in dairy on their own terms while commodity markets churn.

4. Selling the Herd, Keeping the Land

One other path that’s quietly gaining traction is decoupling from daily milking operations while retaining the land asset. This recognizes that, for many operations, the land is where most of the equity lies and that it has value beyond dairy production.

The core idea: sell your milking herd and specialized dairy equipment to a larger operation looking to expand or to a regional buyer aggregating cattle. Keep ownership of the land. Transition to cash crops, custom heifer growing, forage production for neighboring dairies, or long-term leases to mega-operations that want land nearby for manure application and feed production.

Here’s how the math might work in practice:

If you’re running 400 cows, that herd has real value to processors and expanding farms—potentially $600,000 to $800,000 for a quality, productive herd, depending on genetics, production levels, and market conditions. That’s at typical valuations of $1,500 to $2,000 per cow for good producing animals. And again, if you’ve invested in superior genetics—animals with high genomic merit for production, health traits, or specific breed characteristics—you may be able to capture significantly more value by marketing to breeders or genetic-focused operations rather than selling through traditional channels.

Keep your 500 acres of land, worth maybe $3.75 million at $7,500 per acre. Lease it at market rate—say $75 to $100 per acre depending on your region and land quality—and you’re generating $37,500 to $50,000 per year, roughly $3,000 to $4,000 per month.

Now I know what you’re thinking: that doesn’t sound like much compared to milk income. But here’s the key comparison. If you’re currently losing $20,000 per month on the dairy operation, stepping to $3,000 to $4,000 per month in positive cash flow while eliminating all operational stress, labor challenges, and market risk represents a $23,000 to $24,000 per month swing in your financial position. That’s the difference between burning through equity and preserving it.

This approach can stop operational losses immediately, preserve the family’s most valuable asset, maintain income streams through rent or cropping that cover property taxes, insurance, and remaining debt service, and give younger family members time to figure out how they want to be involved in agriculture without the daily pressure and financial stress of milking cows in a negative margin environment.

Industry analysts have noted that when regional processors faced challenges or closures, farms with land assets and flexibility to pivot had far better outcomes than those fully committed to dairy-only operations with no land base. That flexibility increasingly looks like an asset worth preserving, especially given the uncertainty about long-term dairy market structure.

| Strategic Pathway | Equity Preserved | Timeline | Investment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic Sale Pre-Distress | 85% | 6 months | $0 |

| Value-Added Market Pivot | 75% | 18 months | $600,000 |

| Aggressive Asset Optimization | 70% | 12 months | $250,000 |

| Chapter 12 Bankruptcy | 60% | 12 months | $0 (legal fees) |

What You Shouldn’t Do Right Now

Just as important as knowing your options is understanding what to avoid during this window, because some decisions can lock you into worse outcomes.

Avoid investing significant new capital into expansion or major facility upgrades unless you have crystal-clear market access—specific contracts or relationships with processors—and can withstand two to three more years at current margin levels. Agricultural finance advisors have been pretty direct on this point: taking on substantial new debt in a compressed margin environment is the fastest way to convert a struggling operation into an insolvent one. The math is unforgiving.

Be cautious about assuming margin recovery is coming in the near term. The U.S. Dairy Export Council indicated in 2024 market communications that while they’re confident Chinese dairy consumption will eventually return to a growth trend, the timing remains uncertain. Even industry optimists are generally talking 2026 or 2027 for meaningful improvements, and that’s if trade relationships normalize and other market factors align favorably. Making decisions based on assumed recovery is a bet, not a plan.

Don’t count on government relief specific to dairy arriving to change your situation. The policy signals over the past couple of years have been reasonably clear: the focus is on structural solutions rather than direct payments. That could change with different political dynamics, but you can’t build your financial strategy around maybes.

Don’t rely on cooperative leadership or industry organizations to specifically fight to preserve commodity-oriented mid-sized farms. Their incentives may not align with yours, and recent organizational developments have shown where priorities sit in the current environment. That’s not a criticism—it’s just recognizing the structure we’re operating in.

What you should do instead:

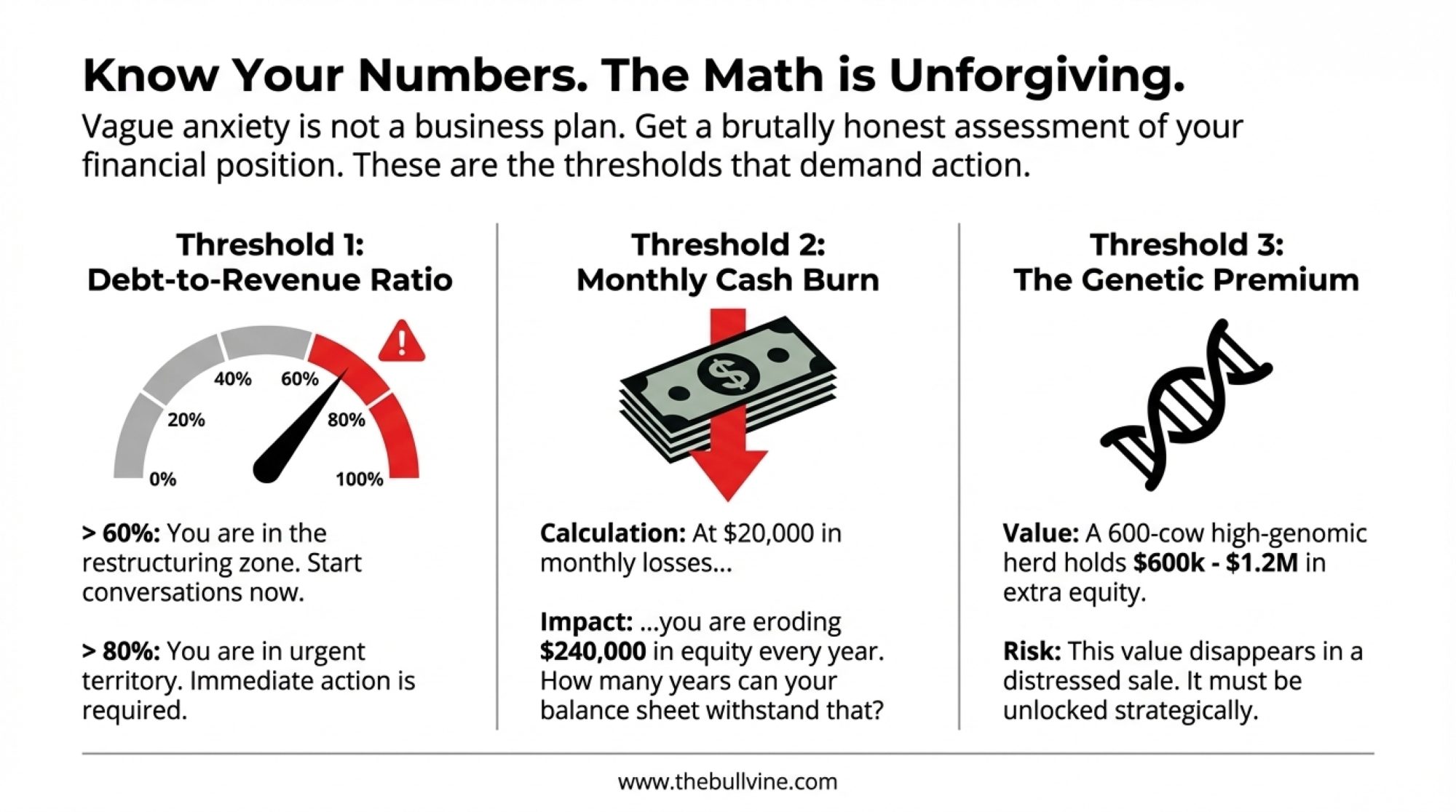

Get a brutally honest financial assessment now. Not an optimistic projection that assumes better markets next year—a conservative stress test that asks: what if margins stay at current levels through 2027? Can we survive that? For how long? At what cost to our equity position?

Understand your true equity position based on current market values for land, facilities, and livestock. Not appraisal values from better times, not what you think things should be worth, but what they’d actually bring in today’s market. And if you’ve got high-genomic animals, get a realistic assessment of their genetic value separate from their production value—that differential could matter significantly in your planning.

Talk to your lenders about restructuring options before the crisis hits. The best time to negotiate is while you’re current on payments and have options. Once you’re in default, your leverage disappears, and the conversation becomes much more difficult.

“Model your debt-to-revenue ratio honestly. If it’s above 60 percent, you’re in the zone where restructuring may be necessary. Above 80 percent, you’re in urgent territory that requires immediate action.”

A Decision Framework You Can Implement This Week

Theory and analysis help understand the environment, but what actually matters is what you do next. Here’s a practical sequence you can start implementing this week, not months from now.

Step 1: Get an Unflinching Financial Picture (Next 60 to 90 Days)

Sit down with your accountant, lender, or trusted advisor and answer these questions with hard numbers, not estimates or hopes:

What’s our true cost of production per hundredweight, including family labor valued at market rates and realistic depreciation that reflects actual equipment replacement timelines? At today’s milk price and current expense levels, what’s our actual monthly profit or loss? How many months of losses at current rates can we sustain before we exhaust operating credit lines or begin meaningfully eroding land equity? What’s our debt-to-revenue ratio, calculated conservatively?

Knowing these numbers precisely turns vague anxiety into concrete decision points. You might find your situation’s better than you feared, and that knowledge gives you confidence to weather the storm. Or you might discover you’re closer to crisis than you thought, and that knowledge pushes you to act while you still have options. Either way, you need to know where you stand.

Step 2: Clarify Your Equity and Exit Value (Next 60 to 90 Days)

Work with someone who knows current markets—a farm real estate professional, an auctioneer who specializes in dairy, an appraiser familiar with your region—to establish realistic values:

What would your land actually sell for today? Not top-of-market hopes or what it was worth three years ago, but realistic pricing based on recent comparable sales in your county. What’s the difference between the cull value for your herd and what you might get selling to another dairyman who wants producing cows? And critically—if you’ve invested in superior genetics, what’s the potential premium you could capture by marketing those animals to breeders or genetic-focused buyers rather than through conventional channels? What would your buildings and equipment bring—auction value versus going-concern value if sold as part of a functioning farm?

This tells you whether a structured sale could preserve significant equity, whether Chapter 12 would protect or destroy more value in your specific situation, and how much capital might be available for a business pivot, retirement funding, or providing next-generation flexibility.

Step 3: Align Strategy with Your Family’s Actual Goals (Next 30 to 60 Days)

This is often the hardest conversation, but it’s also the most important. You need honest answers to difficult questions:

Does the next generation actually want to be dairy, or do they want to farm in some other way? Are they saying what they think you want to hear, or expressing what they genuinely want? Is someone in the family energized by value-added work, direct sales, entrepreneurship, or does everyone just want to produce milk and have someone else handle marketing?

What’s the real priority here: preserving land ownership across generations? Preserving the dairy operation specifically? Preserving family health, relationships, and quality of life? Because in the current environment, you might not be able to preserve all three.

There’s no single right answer to these questions. But the financial and market context we’ve walked through can help keep this family conversation grounded in reality rather than hope, guilt, or assumptions about what previous generations would have wanted.

Step 4: Choose a Path and Set a Timeline (Next 90 to 180 Days)

Once you have clarity on your financial position, your equity situation, and your family’s actual goals, translate that into a concrete plan with specific decision points and dates:

If you’re leaning toward restructuring, schedule consultations with an agricultural bankruptcy attorney and your lender about Chapter 12 and other restructuring options. Set a clear decision deadline: if margins and cashflow don’t improve by this specific date, we file. Start preparing the financial documentation you’ll need so you’re not scrambling when the deadline arrives.

If you’re leaning toward sale or leaseback, quietly begin exploring interest with neighbors, regional operators, or land investors. Prepare clean financials and facility information so you can move quickly when the right opportunity appears. If you have high-genomic animals, connect with breed associations, genetic marketplaces, genetic marketers, or consultants who can help you capture maximum value for those genetics rather than accepting commodity pricing in rushed sales.

If you’re leaning toward a niche pivot—organic, grass-fed, or value-added production—start serious market research right now. Who are the actual buyers? What are the real regulatory requirements and costs? What’s realistic pricing based on current market conditions, not aspirational projections? Explore available grants and cost-share programs through NRCS or state agriculture departments. Sketch a two-to-three-year investment and cashflow plan with conservative assumptions, then stress-test it against downside scenarios before committing.

If you’re considering exiting dairy while keeping the land, identify potential lessees now—neighboring operations seeking additional ground, incoming farmers needing land to rent, and regional mega-dairies requiring nearby acreage for manure management and feed production. Research alternative enterprises that fit your land: what cash crops make sense given your soil types and climate? Are there conservation programs, such as CRP or wetland easements, that provide stable income? Calculate honestly whether lease income, combined with lower-intensity farming, can sustain land ownership over the long term.

The common thread across all these paths: no option is pain-free, and all require difficult decisions. But every proactive option—acting while you still have choices—beats being forced into a rushed, distressed exit after another year or two of heavy losses.

Looking Ahead: Making Decisions You Can Live With. The consolidation pressures, policy dynamics, and global trade patterns hitting dairy right now are bigger than any individual farm can control. You can’t personally fix milk pricing formulas or change how international competitors behave.

But you can recognize the system you’re actually operating in. You can use the next 18 months intentionally. And you can protect the capital and options that will let your family make real choices in 2027 and beyond—whatever those choices turn out to be.

Success in this environment doesn’t always mean staying bigger or staying in dairy. Sometimes it means preserving hard-earned equity, protecting family relationships, and positioning the next generation to chart their own path. The farms still standing five years from now will be the ones whose operators had the courage to make hard decisions while they still had options.

That window’s open now. It won’t stay that way forever.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The efficiency trap crushes margins through no fault of your own: When all regions improve simultaneously, collective productivity creates oversupply that compresses prices—even for well-managed operations executing perfectly.

- High-genomic genetics = undervalued equity: GTPI 2,800+ animals command $2,500-4,000/head vs. $1,500-2,000 commercial. For 600 cows: $600K-1.2M in additional value, but only if marketed strategically before distress forces discount pricing.

- Know your financial thresholds now: Debt-to-revenue above 60% = restructuring territory | Above 80% = urgent action required | $20K monthly losses = $240K annual equity erosion. The math is unforgiving.

- Four strategic pathways, different circumstances: Chapter 12 restructuring (productive operation + heavy debt) | Strategic sale (preserve equity before crisis) | Niche market pivot (proximity + entrepreneurial interest) | Land-retention/herd-sale (immediate loss prevention).

- Strategic action beats waiting for recovery: The farms operating successfully in 2030 won’t be the biggest or most efficient—they’ll be those who moved decisively while equity existed, rather than hoping margins would rebound.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- How to Boost Production by up to 20% through Nutrition and Cow Comfort – Provides a tactical roadmap for maximizing herd efficiency without expansion, detailing specific protocols for feed digestibility and barn environment that can deliver double-digit production gains for mid-sized herds.

- The $11 Billion Reality Check: Why Dairy Processors Are Banking on Fewer, Bigger Farms – An essential strategic analysis exposing exactly how 70-80% of future processing capacity is already contractually locked, helping you assess your operation’s risk exposure in the current market structure.

- Robotic Milking Revolution: Why Modern Dairy Farms Are Choosing Automation in 2025 – Examines the ROI of automation as a labor-force solution, offering comparative data on how robotics can stabilize operating costs and protect margins against the volatile labor market discussed in the main article.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!