One of the saddest pictures I have ever seen was posted on the Internet recently. It was an empty milking parlor that marked the end of a multi-generational family dairy farm. The cows were sold, the hay was gone, the equipment put away. The children would not have the legacy of this farm. Only echoes and concrete remained in the barn.

Sadly, this predicament is all too real for the modern dairy owner. Lately, letters have been sent to farmers from Dean Foods, giving a 90-day notice for producers to find a new milk buyer. Dean Foods is the contractor for Walmart’s Great Value milk. While not blaming Walmart for this tragedy, the regions where contracts were lost encompasses the location of Walmart’s new bottling plant. Processors are also shipping milk in from other states to take advantage of low prices. After surviving two years of extremely low prices, over one hundred farms have lost contracts in the past few weeks. Companies blame a surplus of milk, but individual producers say this is more than a swing of the market.

Many processors have felt the impact. Some combat this by increasing hauling fees, taking away quality premiums, and charging for milk tests that help farmers with feed efficiency. Many farmers won’t protest this for fear of their contracts being dropped.

Many processors have felt the impact. Some combat this by increasing hauling fees, taking away quality premiums, and charging for milk tests that help farmers with feed efficiency. Many farmers won’t protest this for fear of their contracts being dropped.

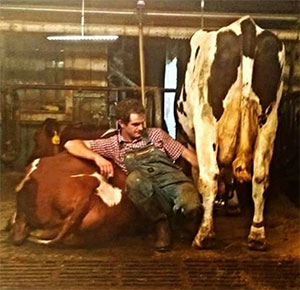

My friend Tristan is one of these steadfast producers, moving to Wisconsin when the dairies dried up in his home state of Missouri. He met his wife, Meg, and they literally combined dairy herds, from getting married in a livestock auction barn to spending honeymoon money on cows and a combine. Tristan and Meg milk 60 cows, farm 500 acres and rely on other ag endeavors to make ends meet.

Both Tristan and Meg start each day by cleaning stalls, milking and feeding each cow a specific diet for her individual needs. At the evening milking, they groom the cows, scratch their backs for them, and clean hooves. They each have their favorite cows, too. Tristan says, “Every cow is named and Meg and I can name them all off by heart. It’s a very fulfilling life, yet very sad at the same time. We bring these girls into the world by delivering them ourselves. We spend each and every day of our lives together twice a day. We give them help when they are sick. I know Meg and I are going to be in tears when we see two of them go through the sale barn tonight.” These two have seen a 60% decrease in their dairy income.

These issues affect every aspect of a dairy family’s life. Milk checks are cut and divided between multiple organizations that advertise and market for the dairy company. But even that comes to a halt when a contract is dropped. Without a buyer for their milk, most dairymen won’t be able to get loans for seed and other farm necessities What many consumers don’t know is that termination letters and final milk payments often come with suicide hotline numbers.

But what can we do? Many encourage buying extra dairy products. Milk, buttermilk and cheese can all be frozen. Trying to buy from smaller dairies also helps producers. You can find out where your milk is from by entering in the bottle code at www.whereismymilkfrom.com. The website also includes a map to find your local dairies. Producers also ask that you call your congressmen and let them know how important family dairy farms are.

I asked Tristan what he wanted consumers to know. He says, “We do the best we can for our livestock, not because it is the most profitable, but because it is the right thing to do. We are stewards of God’s creation and that’s something we hold sacred. The next time people complain about the price of food, remember the people who put food on their tables often don’t have enough on their own. Please support your local family farmer.”

So please, let’s do our part to make sure the family dairy doesn’t disappear into idealistic storybooks. Let’s give these hardworking producers a future. Let’s make sure their farms stay in the family and their children will have calves to bottle-feed. Let’s do what we can, whether we raise livestock, tend orchards, or farm row crops. We are in this together. As Tristan says, “I’m a fourth-generation dairyman and I pray I’m not the last.”

Source: Growing Wisconsin