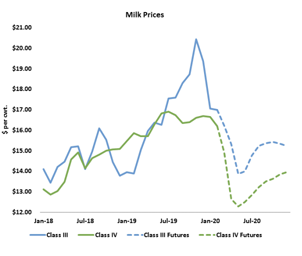

Those numbers clearly won’t pay the bills, and after four painful years (and a couple good months) dairy producers are in no shape to weather this storm. Congress set aside billions of dollars for agricultural aid and for food purchases as part of its $2 trillion aid package, but the timing and structure of these payments are still unknown. The dairy safety net will provide a financial cushion for those who enrolled, but low participation in these programs reveals that many are vulnerable to the whims of an increasingly cruel market. Dairy producers insured quarterly floor prices on about 20% of the nation’s milk through Dairy Revenue Protection (DRP). Barring a steep recovery in milk prices, most of these policies are projected to pay indemnities. Less than half of all dairy producers representing 56.2% of the nation’s established milk production history – and a somewhat smaller share of today’s greater milk production – enrolled in the Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) program, which is now projected to make payments in March through December. It’s likely that many dairy producers who signed up for DRP also enrolled in DMC, so much of the nation’s milk will be sold at very low values, without any safety net protections at all. Unless creditors are exceedingly patient, the industry is likely to suffer a tidal wave of sellouts.

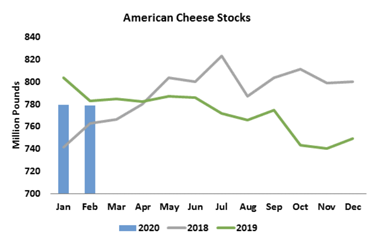

The cheese market was much healthier coming into the crisis. Cheese stocks climbed only slightly from January to February. At 1.36 billion pounds, February cheese stocks were 0.5% lower than a year ago.

Sales patterns are similar in Europe, with cheese moving in large volumes through retail channels. However, some European cheesemakers are finding it difficult to obtain the materials necessary to repackage bulk cheese into retail-friendly sizes. As the bloc struggles to contend with border controls for the first time in decades, bottlenecks are slowing the flow of product from the warehouse to grocers. That’s likely to translate into lost demand despite robust consumer appetites. European cheese stocks were tight before Covid-19 slowed markets. European cheese production grew just 0.3% year-over-year in 2019, and exports impressed. In January, Europe sent 19% more cheese abroad than it did the year before.

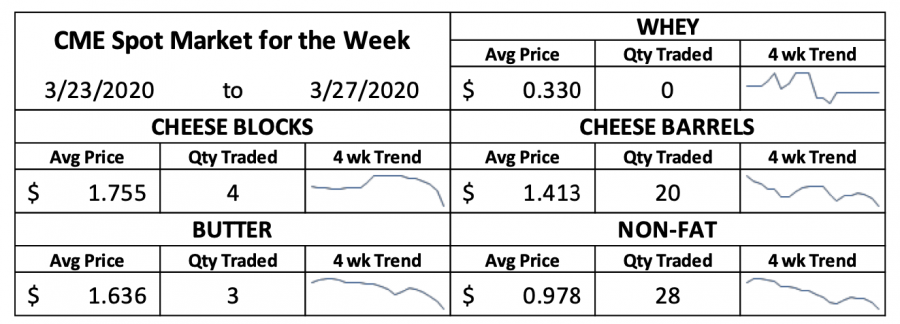

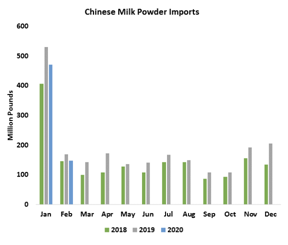

They spot whey market is holding steady, which is a victory in this environment. CME spot whey powder didn’t budge this week; it stands at 33ȼ per pound. The futures gained ground. In January and February, China imported 4.6% more whey than in the first two months of 2019, after adjusting for Leap Day. The U.S. continues to regain market share now that China has rescinded its punitive tariffs on U.S. whey.

Ethanol plants are slowing output or closing their doors altogether, disrupting the feed markets throughout the Corn Belt. The corn basis had been sky-high since the rains became problematic last spring, but now the basis is close to zero in much of the Corn Belt. Cash corn values are down hard. Dairy

producers and other livestock growers who fed distillers grains will have to adjust their rations, which likely means more soybean meal purchases. Unfortunately, soybean meal is one of the few commodities that has been rising in value.

The soy complex got some further support this week from fears that Argentina would halt exports. Port workers are demanding closures so that they can stay home until the virus recedes. But Argentina depends on export taxes and is likely to try to keep product moving, albeit at a slower pace.

May soybeans closed at $8.815, nearly 20ȼ higher than last Friday. At $323.10, soybean meal fell back $2.10 per ton after a sizable rally last week. The corn market inched upward from last week’s multi-year lows. May corn settled at $3.46 per bushel, up 2.25ȼ.

Source: Jocoby