Today’s dairy cows have more genetic potential than any generation before them. And yet we’re dropping race-car engines into go-karts and acting surprised when the wheels start coming off.

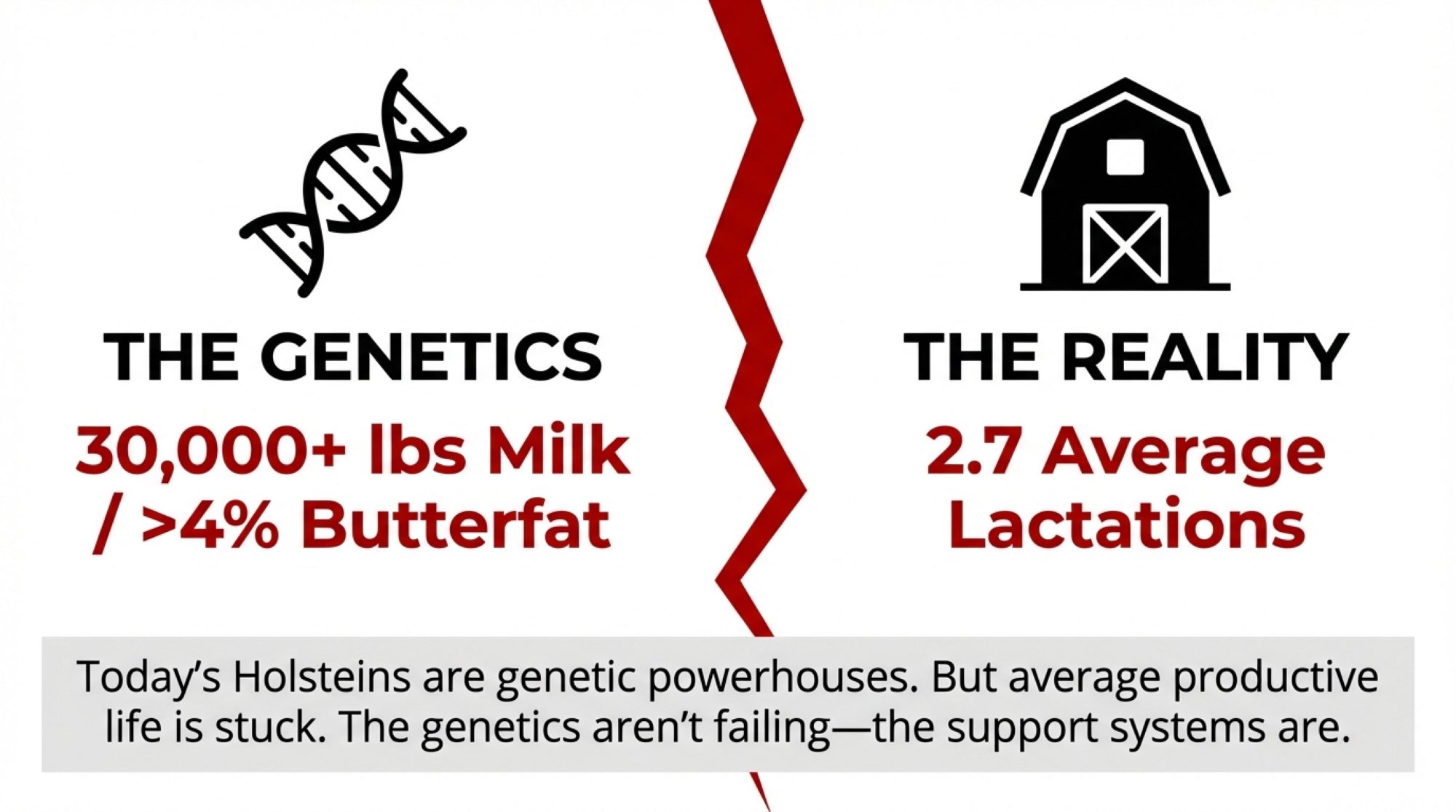

Executive Summary: Today’s elite Holsteins can push 30,000 pounds per lactation with butterfat above 4%—genetic firepower unthinkable a generation ago. Yet average productive life remains stuck at 2.7 lactations, costing the industry billions annually. NAHMS data shows 73% of cows leave herds due to health failures, not strategic decisions—with more than half of on-farm deaths occurring before 50 days in milk. The genetics aren’t failing. The support systems are. Barns, cooling infrastructure, and hoof care protocols were designed for smaller, lower-producing animals. Research from Wisconsin, Cornell, and Florida points to the same leverage points: lying time, heat stress, and lameness. Some herds already average 4+ lactations—proof that closing the gap is possible when infrastructure and execution match the genetics.

There’s a way to think about modern dairy genetics that goes beyond the usual comparisons floating around industry publications.

Consider NASCAR.

A NASCAR vehicle is precision-engineered from the blueprint up, designed to operate at the outer edge of mechanical capability. But here’s the thing—that vehicle only delivers its potential when supported by an elite pit crew, optimal track conditions, and infrastructure designed specifically for high-performance racing.

Modern Holsteins fit this description remarkably well. Elite herds now routinely push 30,000 pounds of milk per cow per year, and national breed averages have recently climbed above 4% butterfat for the first time in U.S. Holstein history, according to breed and DHI statistics. Compare that to the early 1980s, when high-teens production was exceptional for a show cow, and you start to appreciate the transformation genomic selection has brought to the industry.

These animals are championship-caliber machines. The question is whether we’re giving them championship-caliber support.

What keeps coming up in conversations with producers—whether I’m talking with folks in Wisconsin, California, or the Northeast—is a consistent theme: barns, cooling infrastructure, hoof care protocols, and stall dimensions on many operations were designed for a different era. For smaller cows, produced less milk, and generated less metabolic heat.

The genetics have changed dramatically. The infrastructure often hasn’t.

I spoke with a Wisconsin producer last fall who’s consistently hitting 4.2 lactation averages, and his take was illuminating: “We’re not doing anything revolutionary. We’re just doing the basics really consistently.”

Those success stories prove what’s possible when genetics and management align. The reasons more operations haven’t reached that level are complex—and as we’ll explore, often have more to do with economics than knowledge.

What the Numbers Actually Show

Before diving into specific management areas, it helps to step back and look at the broader picture.

According to Penn State Extension analysis of NAHMS data, the average dairy cow in the United States now leaves the herd at approximately 2.7 lactations. That number has been fairly stable for some time, which raises an uncomfortable question: with all the advances in genetics, nutrition, and veterinary care, why hasn’t productive life improved?

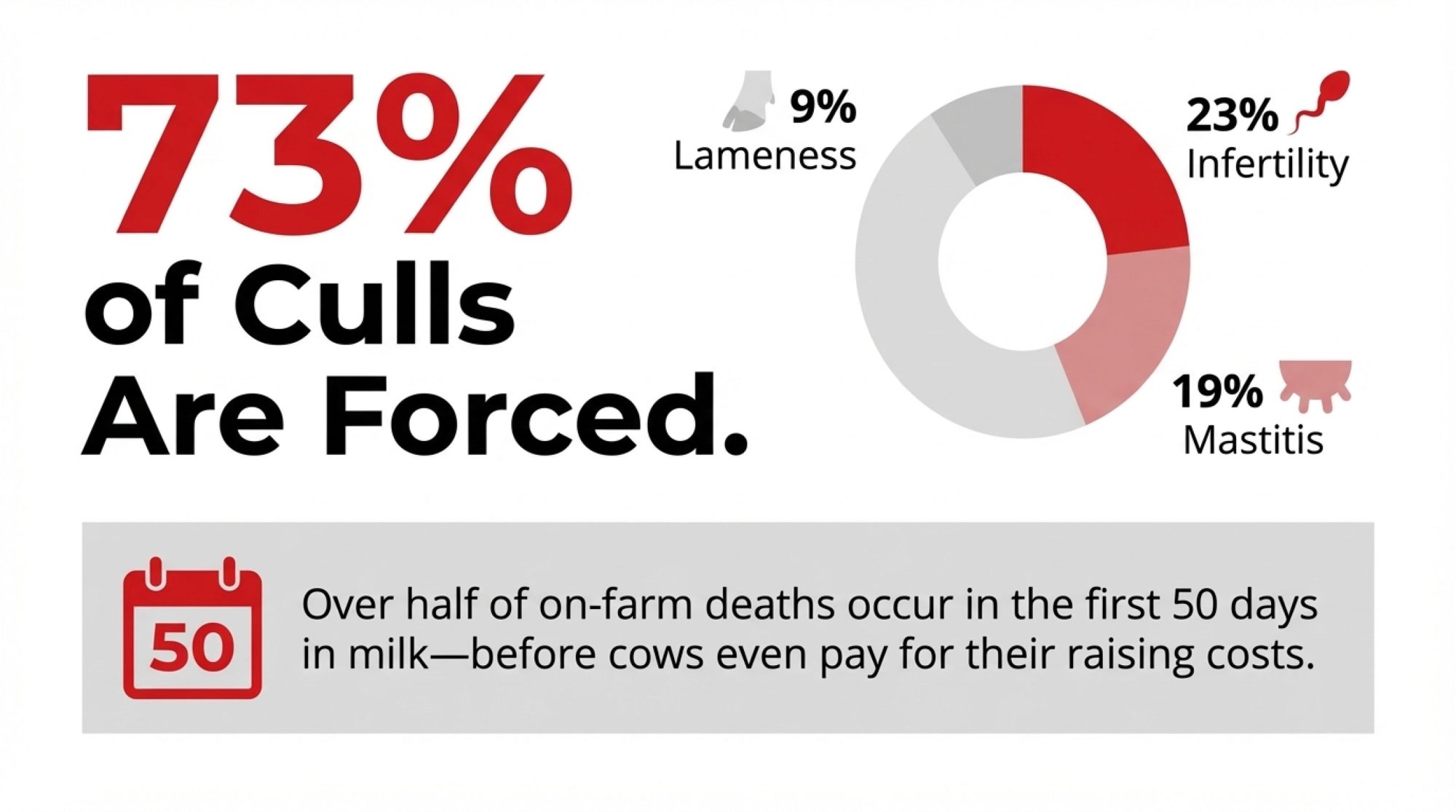

Part of the answer lies in how cows are leaving herds. Research from the Journal of Dairy Science indicates that roughly 73% of culling decisions are involuntary—meaning cows are leaving due to health problems, reproductive failure, or injury rather than strategic herd improvement decisions.

The breakdown tells the story. According to USDA data: infertility leads at about 23%, mastitis accounts for roughly 19%, and lameness drives approximately 9% of forced exits.

What’s particularly sobering—and this caught my attention when I first saw the data—is that more than half of on-farm cow deaths occur within the first 50 days in milk. These are fresh cows. Animals that haven’t yet had the opportunity to pay back their raising costs, let alone contribute to profitability.

Now, some industry observers make a fair point: shorter productive lives aren’t necessarily problematic if genetic improvement means each replacement animal is substantially better than her predecessor. Dr. Albert De Vries at the University of Florida has done extensive work on optimal replacement economics, and his models show that voluntary culling decisions should factor in the genetic merit of available replacements.

But here’s the key distinction: that logic applies to voluntary culls. When 73% of culls are forced by health and reproductive problems, we’re looking at something else entirely—and it’s worth understanding what’s driving those numbers.

The Rest and Recovery Factor

One of the clearest indicators researchers have identified for predicting cow health and productivity is surprisingly straightforward: how much time cows spend lying down.

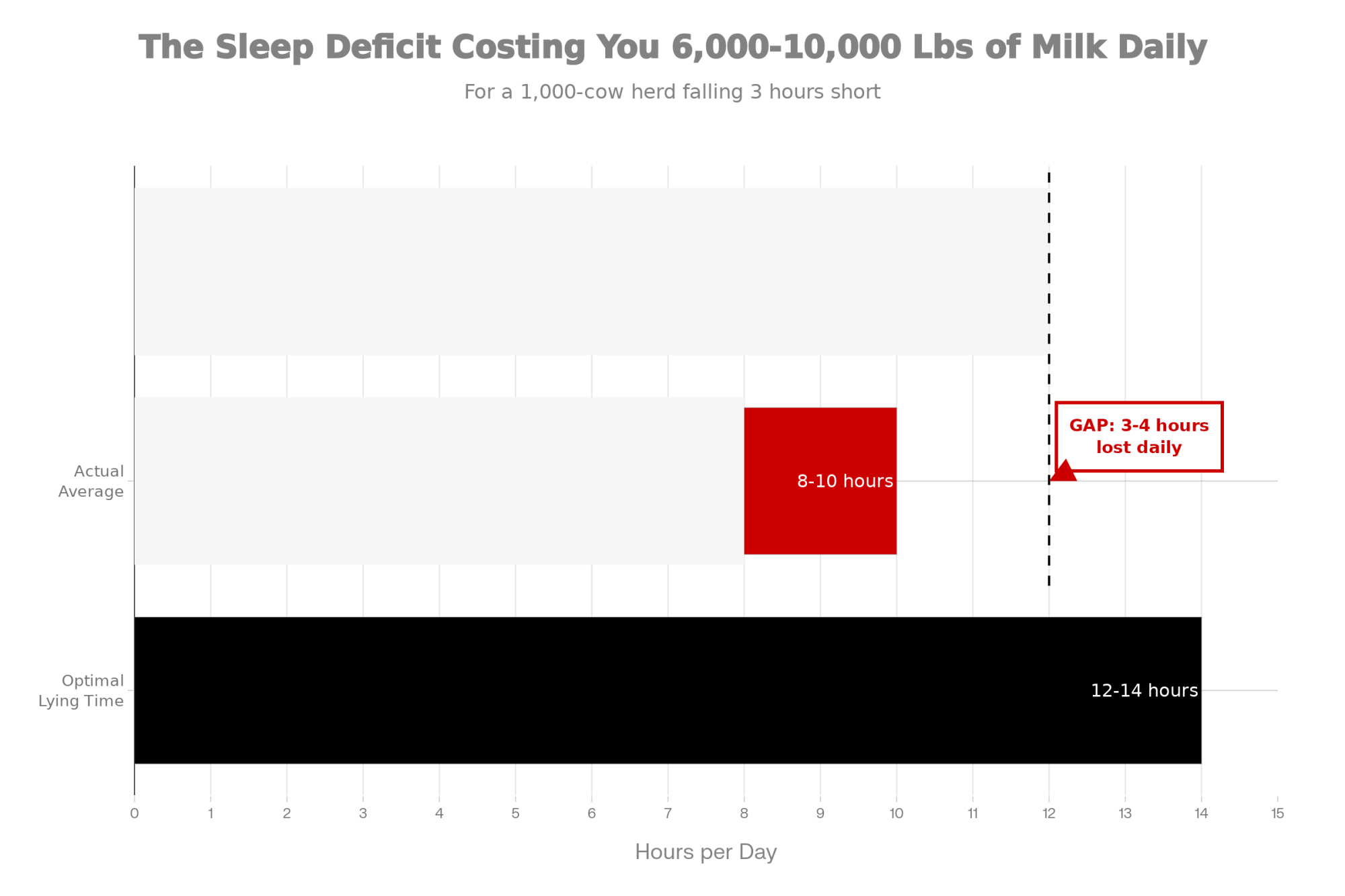

Dr. Nigel Cook at the University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine has been studying this relationship for years. His work, along with research from colleagues at Cornell and the Miner Institute, has established a remarkably consistent finding: every additional hour of lying time (up to an optimal range of 12-14 hours daily) correlates with approximately 2-3.5 additional pounds of milk production per cow per day.

Each hour of lying time a cow loses can cost 2 to 3.5 pounds of milk per day, according to university research summaries. Every single day, that shortfall adds up.

Why does rest matter so much? The biology makes intuitive sense. When cows lie down, blood flow to the udder increases—by 25-30%, according to some estimates. Rumination is more efficient in a lying position. And hoof tissue gets time to dry and recover from constant moisture exposure in alleys and holding areas.

The challenge is that many herds aren’t hitting that 12-14 hour target. Studies using accelerometer data from commercial operations—including research from the University of British Columbia—consistently show average lying times of 8-10 hours in freestall operations. Sometimes, there is less during hot weather or when pens are overcrowded.

For a 1,000-cow herd falling 3 hours short of optimal rest… the math suggests something like 6,000-10,000 pounds of unrealized milk production daily. Over a lactation, that’s significant money left on the table.

What’s Stealing Your Cows’ Rest?

What’s causing the shortfall varies by operation. Sometimes it’s stocking density. Dr. Cook’s research shows that cows lose about 15% of their lying time when stocking density increases from 1 animal per stall to 1.5 animals per stall—a level that’s more common than many producers realize. Other times it’s stall design. Modern Holsteins are simply larger than their predecessors from 20-30 years ago, and stalls built to older specifications may be too cramped for comfortable resting.

The encouraging news? Addressing time barriers to lying often doesn’t require a massive capital investment. Adjusting stocking density, relocating neck rails, and adding bedding depth—these are relatively low-cost interventions that can yield measurable results.

A California producer I spoke with recently reduced stocking from 115% to 100% and saw a 4-pound increase in rolling herd average within 60 days. “I was skeptical,” she told me. “The math said it wouldn’t pay. But the cows told a different story.”

Bedding Systems and the Economics of Comfort

When researchers compare bedding materials, deep-bedded sand consistently ranks at the top for cow health and comfort. This finding has been replicated across studies from the University of Wisconsin, Ontario’s Ministry of Agriculture, and veterinary practices across North America.

The advantages are multi-dimensional. Sand is inorganic, so it doesn’t support bacterial growth as organic materials do. It conforms to the cow’s body, distributing weight and reducing pressure points. And it provides good traction when dry without retaining moisture against the skin.

Dr. Cook’s research has documented that herds on properly managed deep sand show lower rates of hock lesions, reduced mastitis incidence, and longer lying times compared to mattress-based systems.

So why isn’t everyone using sand?

The answer comes down to economics and operational complexity—a theme you’ll notice throughout this discussion. Retrofitting from mattresses to deep sand for a 200-cow barn involves substantial capital investment. Then there are ongoing costs: sand procurement, maintenance of the separation system, increased equipment wear from abrasive material, and additional labor for bedding management.

The payback period—typically 18-24 months when you account for production gains, reduced health costs, and extended productive life—is reasonable for a capital investment. But that upfront requirement presents real challenges, particularly for operations with limited borrowing capacity or uncertain milk price outlooks.

Here’s something worth noting, though. Mattress technology has improved considerably over the past decade. Producers using high-quality foam-topped mattresses with aggressive bedding management—keeping 2-3 inches of clean, dry material on top at all times—can achieve results closer to sand than older research might suggest.

The key, regardless of system, is management intensity. I’ve seen excellent results on sand, mattresses, and even waterbeds when attention to detail is present. And I’ve seen poor outcomes on all of them when management slips.

The Heat Stress Challenge

This is one of those areas where I think the industry conversation is finally catching up with the research—though we’re not all the way there yet.

In warm climates, heat stress is one of the largest drains on productivity and cow welfare. Anyone farming in Texas, Arizona, or California’s Central Valley knows this instinctively. But what strikes me about the economic data is how much larger the impact is than most producers estimate, even experienced ones who’ve dealt with heat stress for decades.

Heat stress costs the U.S. dairy industry $900 million to $1.5 billion annually, according to an economic analysis by the University of Florida and the USDA.

Research from the University of Florida, building on earlier USDA analyses, puts those numbers in stark terms. For individual operations in hot regions, the per-cow impact can reach $500- $700 per year when you account for all cascading effects.

The Hidden Costs Most Producers Miss

Those effects extend well beyond milk production decline during hot weather. Research published in the Journal of Dairy Science has documented reduced dry matter intake (as cows attempt to lower metabolic heat production), compromised immune function leading to higher disease incidence, and impaired reproductive performance. According to Dr. Peter Hansen at the University of Florida, conception rates can drop from 40-50% to as low as 10-20% during heat stress periods.

And there’s a dimension many producers don’t fully appreciate: the effects on developing fetuses can impact the lifetime productivity of offspring. Research increasingly suggests that in-utero heat stress creates lasting changes in immune function and milk production capacity. That’s a long tail on today’s management decisions.

What’s particularly insidious is that damage begins before it’s visually obvious. Research using Temperature-Humidity Index measurements indicates that production impacts begin around THI 68—a threshold crossed more often than many producers realize, even in traditionally “cooler” regions. Modeling and on-farm monitoring show that even in states like Wisconsin and Minnesota, herds frequently experience many days each summer above that threshold, enough to reduce milk yield and fertility measurably.

I’ve spoken with upper Midwest producers who were genuinely surprised to learn that their herds were experiencing measurable heat stress on so many summer days. We tend to think of heat as a southern issue, but the data tells a more nuanced story.

Once THI climbs past about 68, most high-producing herds start to lose milk, whether we see obvious signs or not.

The good news? Cooling infrastructure has become more sophisticated and, in many cases, more affordable relative to its impact. Holding pen cooling tends to offer the fastest payback (since cows are concentrated and often heat-stressed from walking to the milking area and waiting for milking). Feedbunk soakers combined with fans can maintain intake during hot weather. Tunnel or cross-ventilation systems provide consistent air movement but require more substantial investment.

Lameness: The Quiet Productivity Drain

If there’s one area where the gap between research knowledge and on-farm execution is most pronounced, it might be lameness prevention.

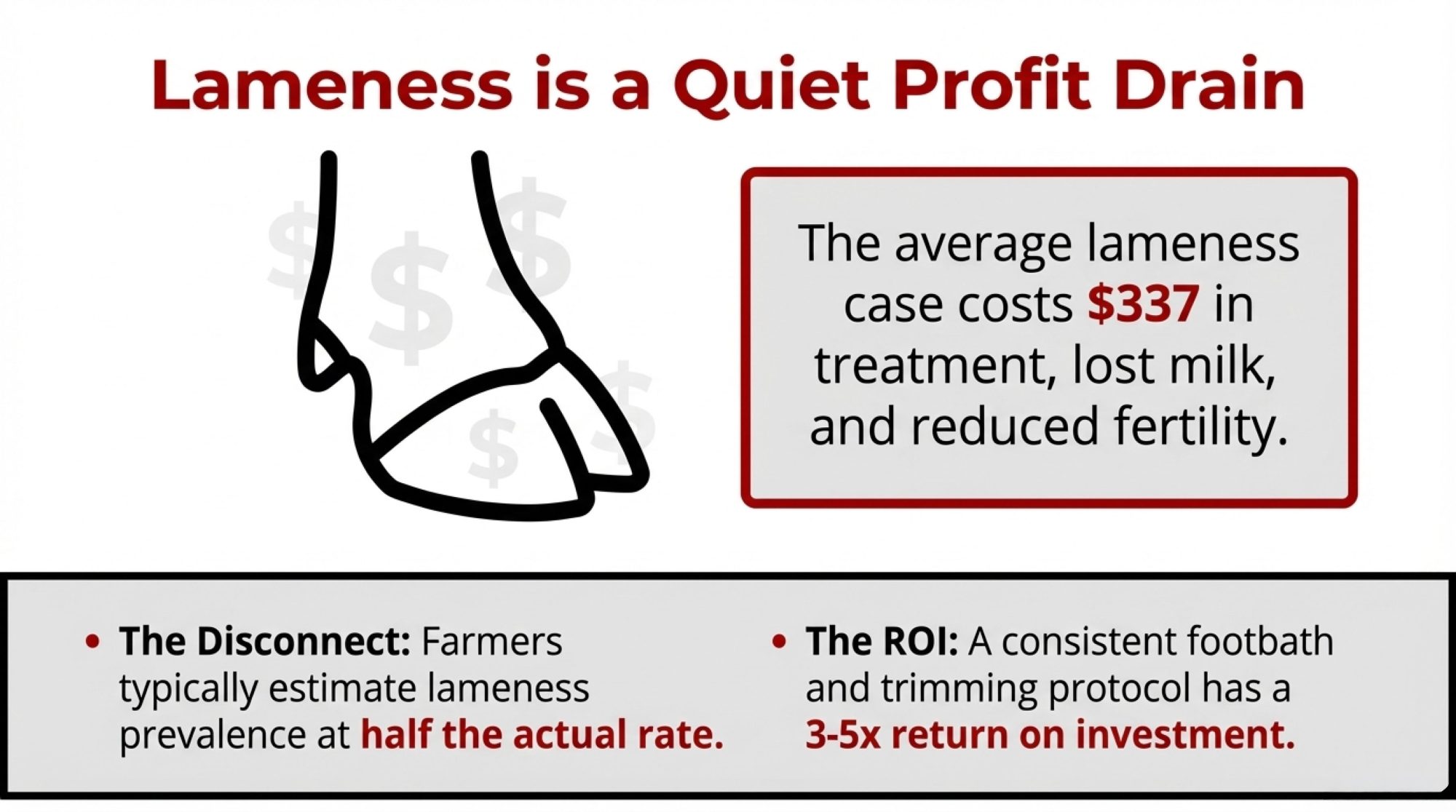

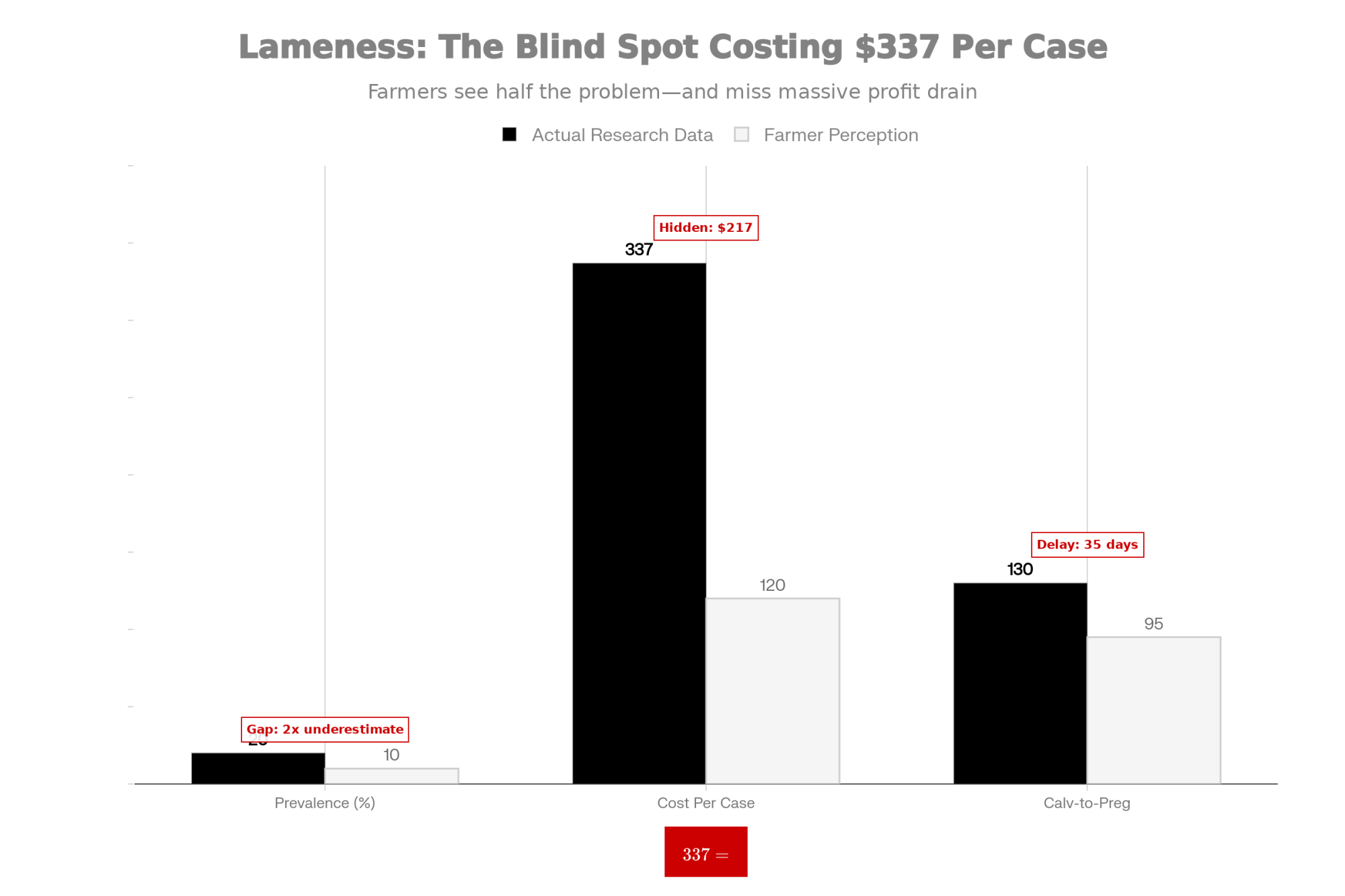

The economics are clear—almost surprisingly so. Research from multiple universities estimates the cost of a single lameness case at $90-$340, depending on severity and duration. A 2023 study by Robscis and colleagues found the average to be $336.91 per case, accounting for treatment, milk loss, and reproductive impact. That number surprised me when I first saw it—it’s considerably higher than most producers estimate when you ask them to ballpark the cost of a lame cow.

Research in Preventive Veterinary Medicine found that lame cows show calving-to-pregnancy intervals 30-40 days longer than sound herdmates. Perhaps most striking: a substantial portion of culls attributed to reproductive failure actually trace back to lameness as an underlying cause. When cows hurt, they don’t show heat as strongly, they’re harder to breed, and they’re more likely to leave the herd before their genetics can express.

The prevention protocol isn’t complicated. Extension recommendations consistently emphasize regular hoof trimming (2-3 times per lactation, with particular attention at dry-off and early lactation), consistent footbath protocols (4+ treatments per week with proper bath design), attention to walking surfaces, and management of stocking density to reduce the time cows spend standing in alleys.

Ohio State Extension estimates footbath costs at roughly $42 per cow annually for a properly executed copper sulfate program. Add in professional trimming, infrastructure maintenance, and labor, and a comprehensive program for a 200-cow herd runs $15,000-$25,000 per year. The return on that investment—when accounting for prevented cases and their cascading effects—typically exceeds the cost by a factor of three to five.

So why the disconnect between knowledge and action?

Research on farmer behavior points to several factors. Farmer-estimated lameness prevalence typically runs about half of the actual prevalence when researchers conduct independent scoring. Many cases simply aren’t being recognized, particularly in early stages when intervention is most effective. I’ve walked pens with producers who consider their lameness “under control,” only to find prevalence rates above 20% when we systematically score.

There’s also the challenge of sustained execution. Unlike a capital investment that pays back automatically once installed, lameness prevention requires daily attention and consistent protocols. When labor is stretched, and competing priorities emerge, footbath management and trimming schedules often slip.

This isn’t about producers being careless—it reflects the reality of managing complex biological systems with finite time and attention. But it suggests that farms with the labor capacity to implement the protocol consistently may have an underappreciated competitive advantage.

The Replacement Economics Puzzle

Behind many of the management decisions we’ve discussed lies a deeper economic reality reshaping dairy operations in fundamental ways.

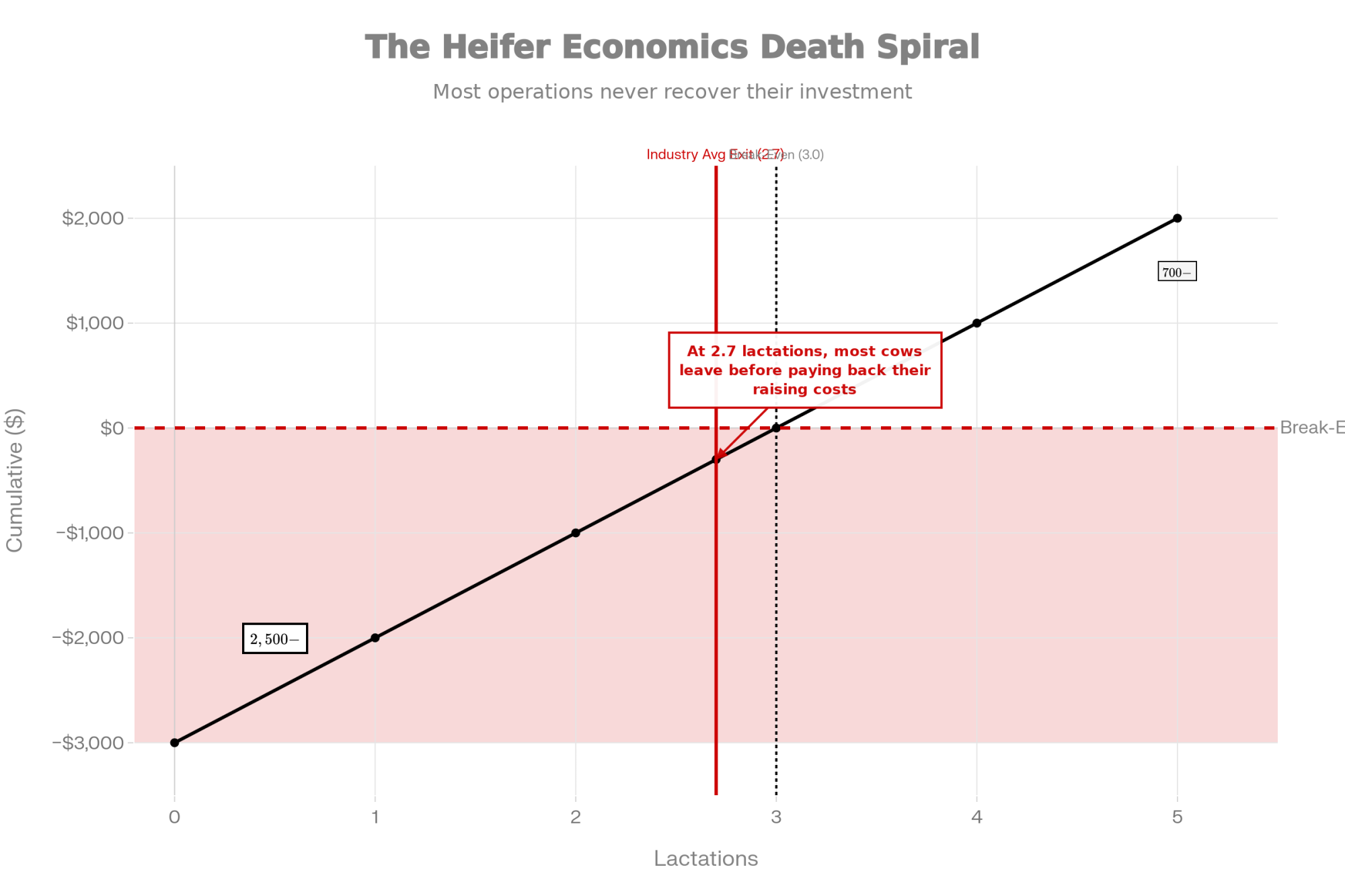

The cost of raising a replacement heifer from birth to first calving now ranges from $2,500 to $3,500, depending on region and management intensity. Market prices for springing heifers have reached $2,800-$4,000 in many regions—a significant increase from 2019 levels.

Here’s where the math gets challenging. Penn State Extension analysis indicates it takes over 3 lactations for a producer to recoup heifer-raising costs. Other research—including Dr. De Vries’s work at Florida—suggests that fully paying back the investment may require 5-7 lactations under some economic scenarios.

With an average productive life at 2.7 lactations, most operations are at real risk of not fully recovering their heifer-raising costs before cows leave the herd. That’s a structural problem that no amount of good management can fully overcome.

At an average of 2.7 lactations, most operations are coming uncomfortably close to losing money on the heifers they raise, once all costs are honestly accounted for.

The beef-on-dairy trend has intensified this dynamic. In many U.S. markets over the past year, day-old beef-on-dairy calves have routinely brought $700 to over $1,000, with some reports of top lots averaging close to $1,400 per head during the strongest runs. The immediate cash flow is attractive, and on a per-calf basis, the economics make sense.

But the collective effect has been dramatic. USDA cattle inventory data show U.S. dairy replacement heifer numbers at their lowest level in decades, comparable to the late 1970s. That supply constraint has driven prices to record levels, making it difficult, from an economic standpoint, to raise and buy replacements.

What this means practically is that many operations have reduced culling rates—keeping older cows in production longer because replacements are either unavailable or unaffordable. Industry reports indicate dairy cow slaughter in 2024 has run noticeably below the levels seen in many recent years, reflecting tighter replacement supplies and strong milk prices in some regions.

This isn’t necessarily negative from a longevity perspective. Keeping cows longer is, after all, what the industry has long encouraged. But it changes the management calculus. An older herd with more health challenges requires different attention than a younger herd, and operations that haven’t adjusted protocols may find themselves stretched thin.

What Operations Breaking Through Look Like

Despite these challenges, some operations achieve substantially better longevity outcomes. Looking at what they have in common offers a useful perspective.

Deliberate intensity management: Some high-longevity operations have consciously moderated peak production in favor of more sustainable output over time. Research from Germany and the Netherlands has documented herds averaging 4+ lactations with peak yields intentionally held 10-15% below maximum genetic potential. Less milk per lactation, but more lactations per cow—and the lifetime productivity often pencils out favorably.

Lower debt burden: Operations with debt-to-asset ratios below 40% are more flexible in making infrastructure investments and weathering price volatility. Highly leveraged operations often can’t afford capital improvements that would reduce their costs over time—a challenging cycle.

Strategic heifer programs: Operations raising their own replacements—particularly those using genomic testing to identify high-potential animals early—report significant cost advantages over purchasing from the market. Genomic selection can identify animals with better health and fertility genetics before substantial raising costs are incurred.

These aren’t secret formulas. They’re applications of well-understood principles—but ones that require capital access, operational flexibility, and long-term planning horizons that not every operation enjoys.

Regional Realities

Priorities look different depending on where you’re farming.

For operations in Texas, Arizona, or California’s Central Valley, heat stress mitigation typically offers the fastest return on investment. Production and reproduction losses from inadequate cooling can dwarf other management factors.

In the upper Midwest—Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan—heat stress matters during summer months, but lameness prevention and stall comfort often yield more consistent year-round returns. Longer housing seasons mean cows spend more time on concrete and in freestalls, making lying time and hoof health particularly important.

Northeast operations face their own considerations: older barn infrastructure, smaller average herd sizes, and proximity to premium milk markets that can support different economic calculations.

Labor markets vary significantly, too. Operations in regions with reliable labor availability may find it easier to maintain consistent lameness prevention protocols. Those facing chronic shortages might prioritize automation or simpler systems requiring less daily attention.

Generic recommendations only go so far. The right priorities depend on climate, existing infrastructure, labor situation, financial position, and herd demographics.

Where to Focus Limited Resources

Investment Priorities at a Glance

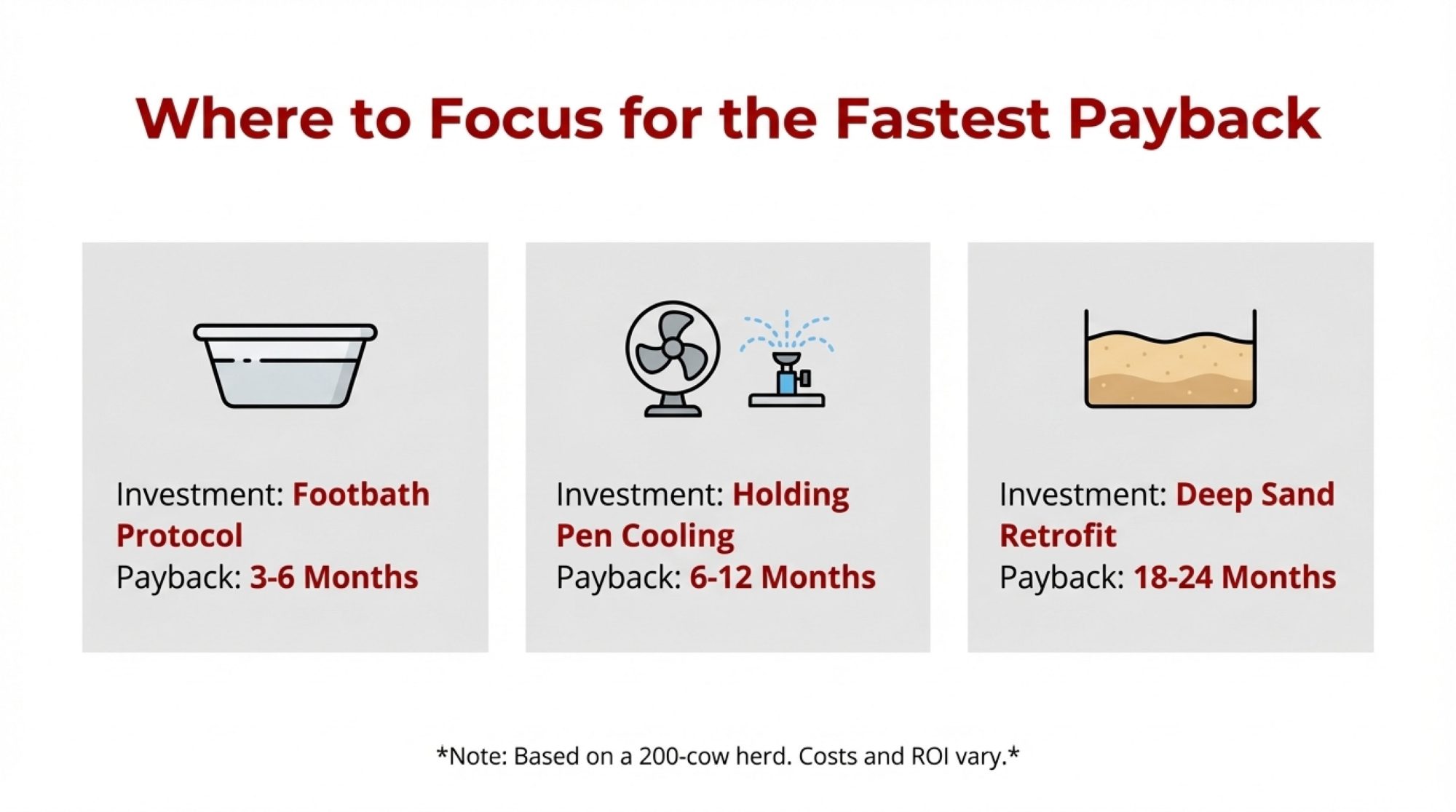

Stocking Density Adjustment

- Capital: $0

- Operating: $0 (may reduce revenue short-term)

- Payback: Immediate

- Benefit: Lying time, herd health

Footbath Protocol Improvement

- Capital: $3,000-$5,000

- Operating: $8,000-$12,000/year

- Payback: 3-6 months

- Benefit: Lameness reduction

Holding Pen Cooling

- Capital: $15,000-$25,000

- Operating: $2,000-$5,000/year

- Payback: 6-12 months

- Benefit: Heat stress reduction

Comprehensive Barn Cooling

- Capital: $60,000-$90,000

- Operating: $8,000-$15,000/year

- Payback: 12-18 months

- Benefit: Production, reproduction

Deep Sand Retrofit

- Capital: $80,000-$110,000

- Operating: $15,000-$25,000/year

- Payback: 18-24 months

- Benefit: Udder health, comfort, longevity

All figures are based on a 200-cow herd. Costs vary by region and existing infrastructure.

Finding Your Starting Point

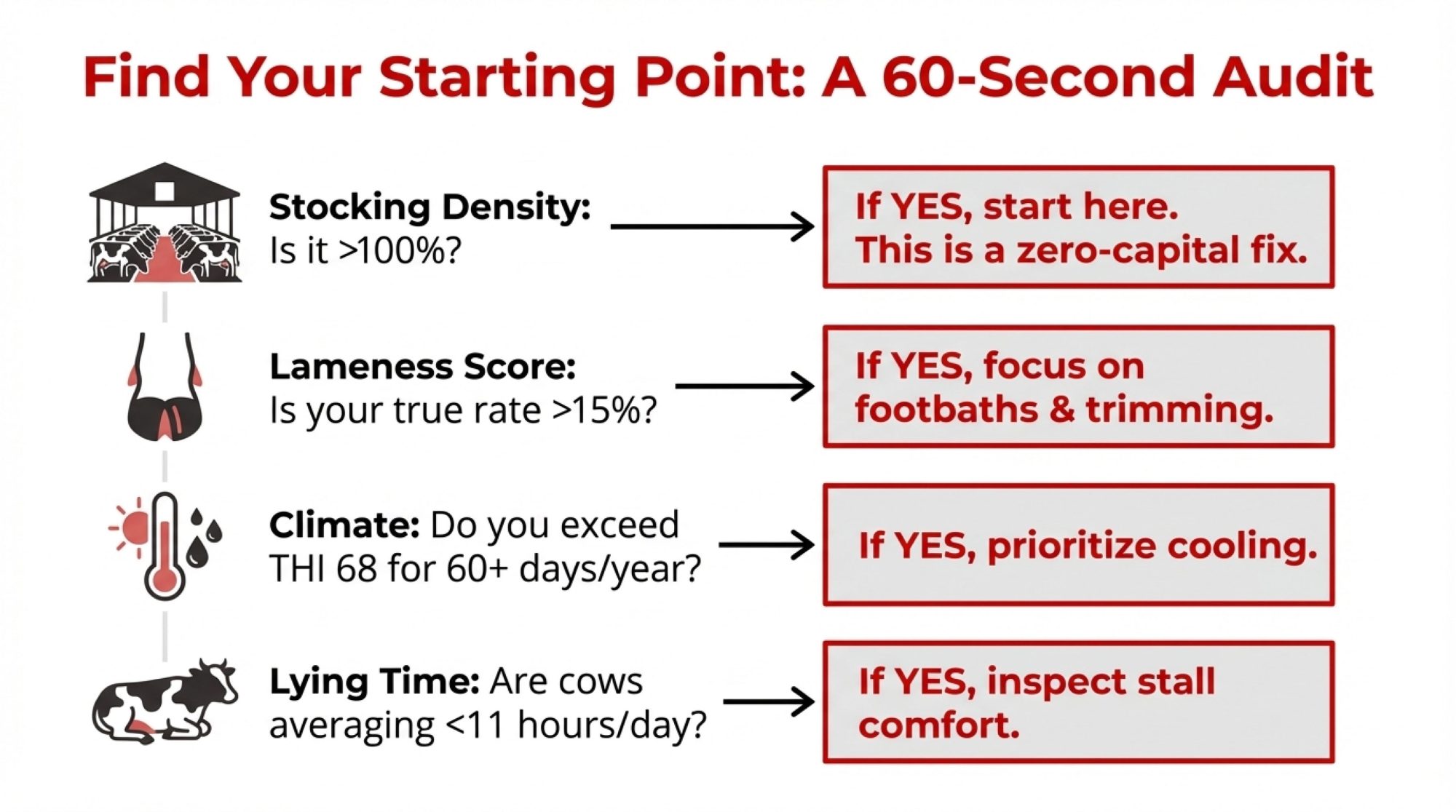

Check stocking density first. Running above 100% of stall capacity? That’s probably your starting point. The best facilities in the world can’t help cows that can’t access them.

Get an honest lameness assessment. Have someone other than regular staff do the scoring—research consistently shows we underestimate prevalence by half. If the true rate exceeds 15%, protocol improvements are likely to yield faster returns than facility investments.

Consider climate exposure. Does your region exceed THI 68 for 60+ days annually? Cooling infrastructure should be near the top of your list.

Evaluate lying times. Cows averaging below 11 hours daily? Look at stall comfort—dimensions, bedding depth, neck rail position.

Review fresh cow mortality. Losing animals in the first 50 days at rates above 2-3%? The issue is likely transition management, not facilities.

Consider financial position. Debt-to-asset ratio above 50%? Focus on cash-flow-positive improvements first—protocol consistency and management intensity often deliver returns without requiring additional capital.

The Bottom Line

Stepping back from all of this, what becomes clear is that the gap between genetic potential and realized performance isn’t primarily a knowledge problem. The research is available. The protocols are documented. Most producers know what best practices look like.

A lot of this comes back to structure, not just day-to-day decisions. Capital constraints limit infrastructure investment. Labor constraints limit protocol consistency. Price volatility makes long-term planning difficult. Replacement economics create challenging trade-offs between immediate cash flow and long-term herd value.

Individual operations can make meaningful improvements within these constraints—and many are doing so. Herds achieving 4+ lactation averages demonstrate that matching management to genetics is possible.

But there’s growing recognition in industry discussions that some challenges may require broader solutions: pricing systems that reward longevity, risk management tools that support infrastructure investment, cooperative models that improve capital access for mid-sized operations. These are conversations worth having, and we’ll be exploring some of these systemic questions in upcoming coverage.

In the meantime, genetics continue to improve. Each generation carries more potential than the last. The cows are ready for championship performance.

The opportunity—and it’s a real one—is building support systems to match. It won’t happen overnight. It won’t look the same on every operation. But for producers willing to honestly assess their limiting factors and strategically focus resources, meaningful progress is achievable.

One management decision at a time, the gap between genetic potential and realized performance can narrow.

The pit crew can rise to meet the machine.

Key Takeaways

What the research shows:

- Modern genetics deliver unprecedented production potential, but the average productive life remains around 2.7 lactations

- Lying time, heat stress management, and lameness prevention show strong connections to longevity and lifetime productivity

- Infrastructure investments typically show 12-24 month payback periods—solid returns, but requiring upfront capital

Practical priorities:

- Start with an honest assessment of lying time and stocking density—often the highest-impact, lowest-cost interventions

- Regional climate should guide investment priorities

- Consistent protocol execution may matter more than facility perfection

- Evaluate heifer economics given current market conditions—the math has shifted significantly

The bigger picture:

- The gap between genetic potential and realized performance is more about economics and execution than knowledge

- Operations achieving exceptional longevity share common characteristics: manageable debt, consistent protocols, long-term planning horizons

- Industry-level discussions about pricing and capital access will shape what’s possible going forward

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Heat Stress 2.0: Why Your Current Cooling Strategy Is Costing You Big Money – Provides a tiered implementation plan for upgrading cooling infrastructure, moving beyond basic fans to advanced systems that prevent the $700 per cow losses often missed in standard audits.

- America’s 800,000-Heifer Crisis: How Chasing Beef Premiums Broke Our Replacement Pipeline – diverse deep into the structural inventory collapse driving replacement costs to record highs, offering critical market intelligence for producers navigating the trade-offs between beef-on-dairy cash flow and future herd security.

- Robotic Milking Revolution: Why These Money Machines Are Crushing Traditional Parlors – Examines how automated milking systems act as the ultimate “pit crew” upgrade, solving labor consistency challenges and delivering the precise 365-day execution required to realize full genetic potential.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.