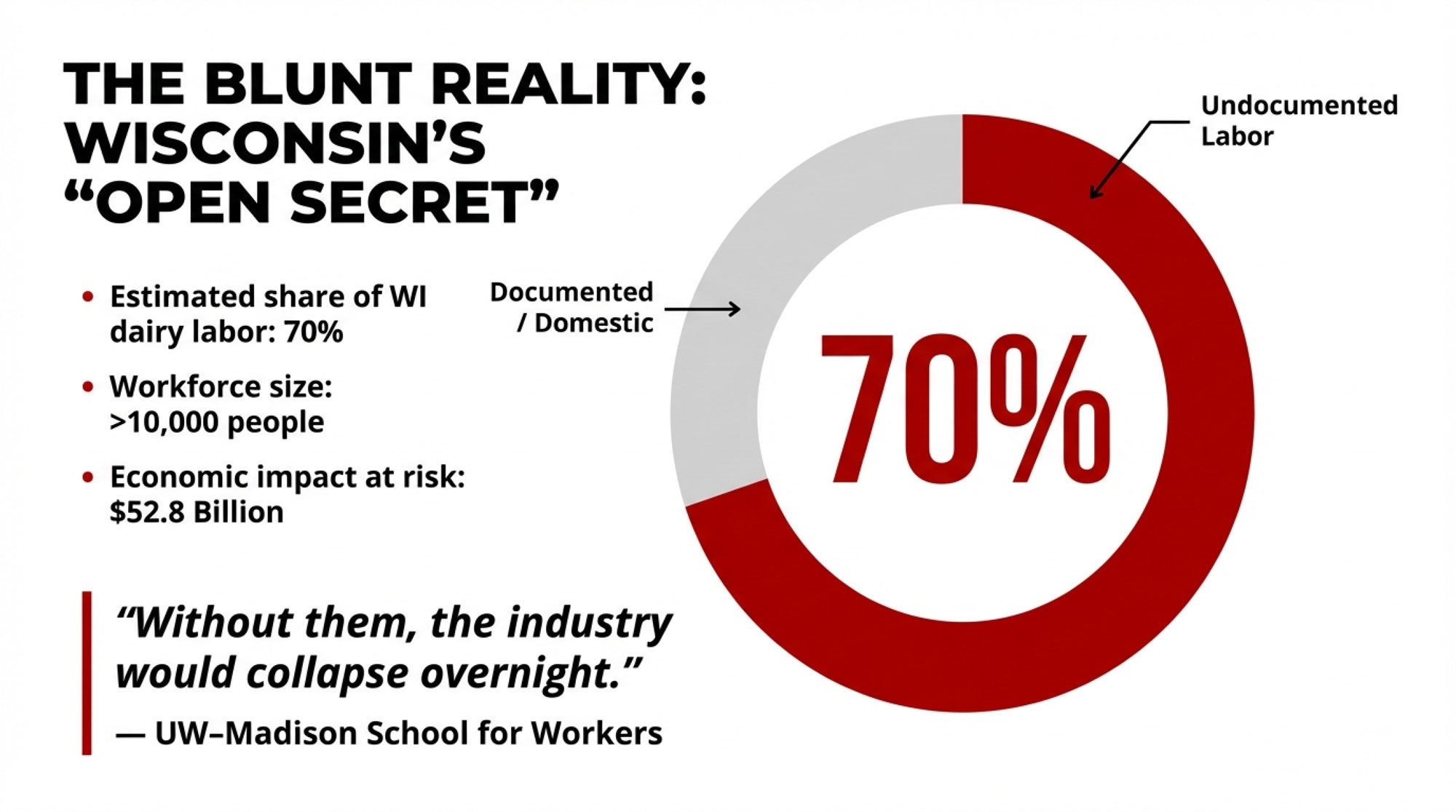

It is estimated that 70% of Wisconsin dairy labor is undocumented. For a 500‑cow herd, the new reality is blunt: pay more people, buy robots, or plan your way out.

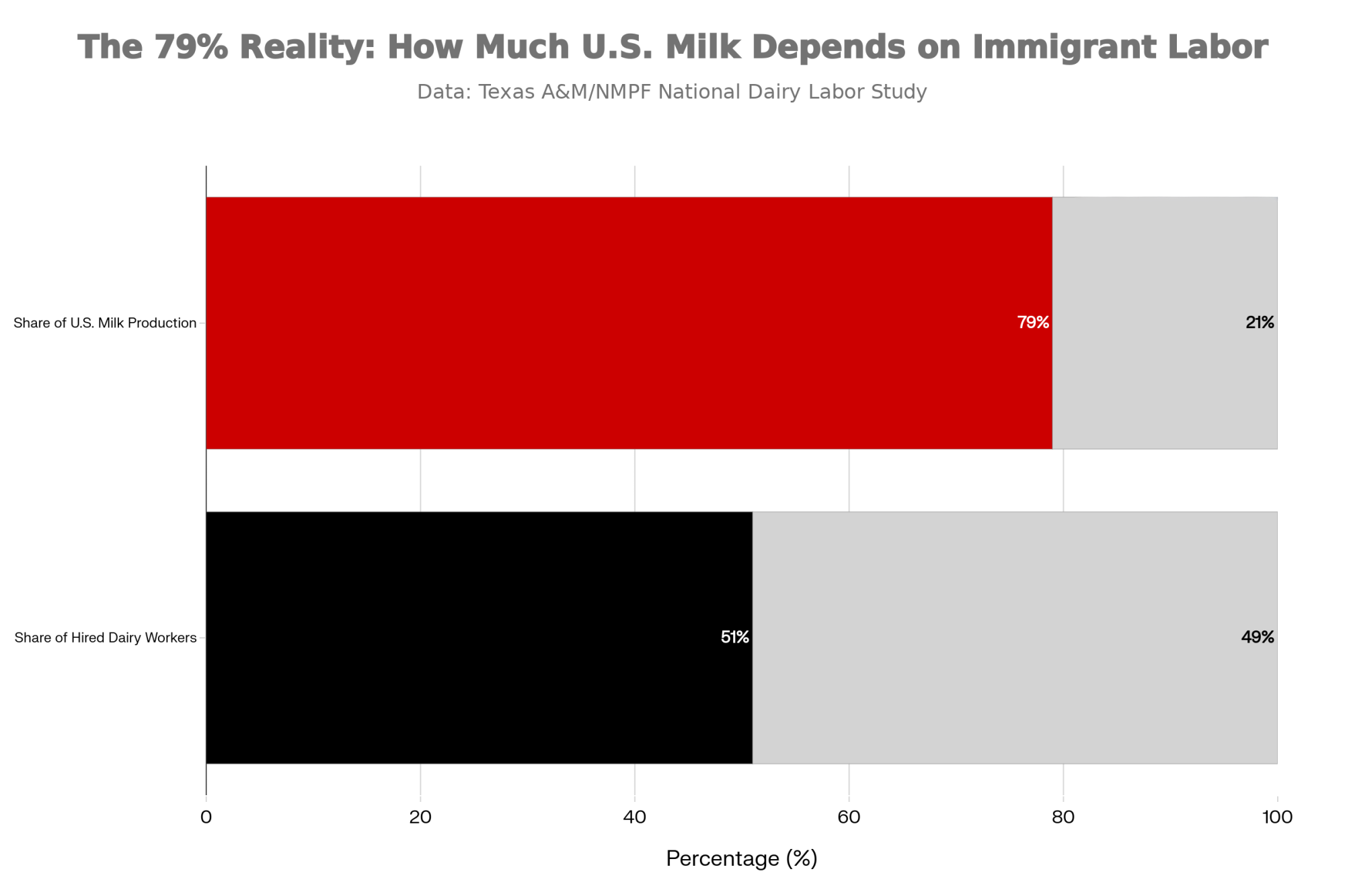

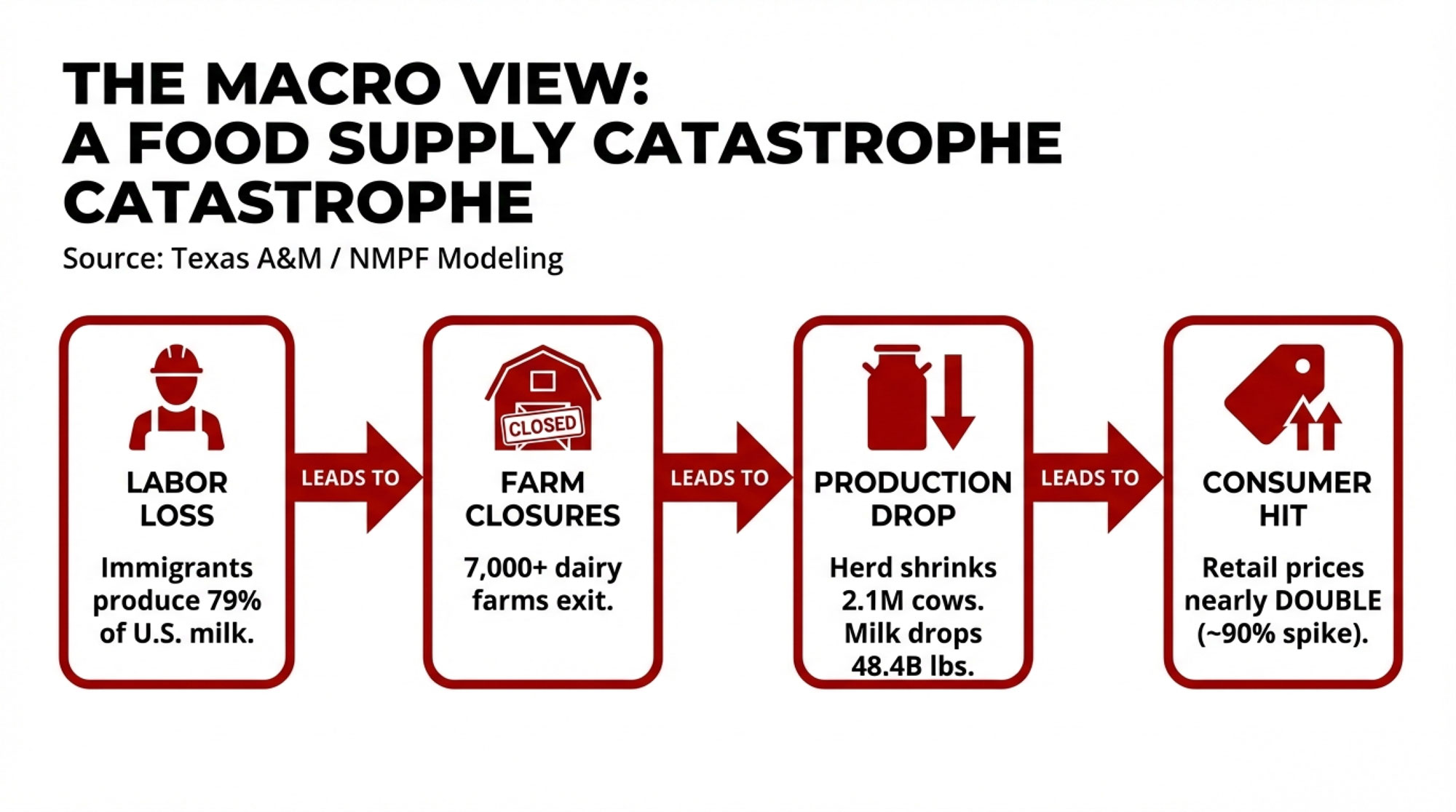

Executive Summary: Wisconsin dairy is riding a knife-edge of labor. A UW–Madison School for Workers survey estimates more than 10,000 undocumented workers now perform about 70% of the state’s dairy labor, while a Texas A&M/NMPF study shows immigrant workers make up 51% of all hired U.S. dairy labor and produce 79% of the nation’s milk, with their loss projected to close over 7,000 farms, cut 48.4 billion pounds of milk, and nearly double retail prices. At the same time, updated UW–Madison/DATCP figures show dairy is generating $ 52.8 billion a year and 120,700 jobs in Wisconsin, so any shock to that workforce hits the entire rural economy. Against that backdrop, this article walks through a 500‑cow, 30‑day “labor shock” in which 40% of the crew disappears, showing, in barn‑level detail, how milking schedules drift, fresh cow management and transition‑period care get squeezed, butterfat performance slides, and fatigue and overtime chew into already thin margins. From there, it lays out the two main survival paths herds are actually using—paying higher wages and building stronger people systems to keep a more legal, stable crew, or investing in automation, especially robotic milking, to permanently cut labor hours per hundredweight—while giving H‑2A a fair, honest look as a partial tool rather than a fix‑all. It also explains how those choices ripple through processors, co‑ops, and local businesses, and how lenders are increasingly favoring farms that treat labor as a strategic risk rather than a background headache. Most importantly, it closes with a concrete, kitchen‑table playbook of questions and scenarios you can use to map your own labor exposure, run the math on wages versus robots, talk with your lender and family, and decide whether your farm’s future is as a top‑tier employer, a tech adopter, a niche player, or an operation that plans its exit on its own terms.

If we were talking this through over coffee at a winter meeting instead of on a screen, I’d probably start with something you’ve seen brewing for a while, even if it hasn’t hit your own yard yet.

In 2024 and 2025, immigration enforcement stepped squarely into Wisconsin’s dairy world. Investigative pieces from outlets like Wisconsin Watch and The Fulcrum have documented how federal immigration actions swept up workers tied to dairy farms, and how families sometimes spent days trying to figure out where husbands, wives, or parents had been taken and what would happen next, based on interviews with immigrant support groups and attorneys. You know how that goes—kids still need to get to school, cows still need to be milked, but nobody’s quite sure who’s walking back through the door tonight.

Here’s what’s interesting. As those stories hit the news, they didn’t really surprise many people actually milking cows in this state. A 2023 survey by the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s School for Workers found that more than 10,000 undocumented workers perform around 70% of the labor on Wisconsin’s dairy farms, and the authors didn’t mince words when they discussed it publicly: they said that without those workers, Wisconsin’s dairy industry would “collapse overnight,” a phrase picked up by Wisconsin Watch and Urban Milwaukee in 2025 summaries of the data. That 70% figure reappears in the School for Workers’ “As we move to 2025” update and in commentary by Wisconsin labor advocates explaining just how dependent dairy has become on that workforce.

And when you zoom out nationally, the dependence is just as stark. A major study from Texas A&M University’s Center for North American Studies, led by agricultural economists including Dr. Parr Rosson and funded by the National Milk Producers Federation, surveyed U.S. dairy farms on their use of immigrant labor. That work found that immigrant workers make up about 51% of all hired workers on U.S. dairy farms and that farms employing immigrant labor produce roughly 79% of the country’s milk. In their economic model, if those immigrant workers vanished, the U.S. would lose just over 7,000 dairy farms, the national herd would shrink by about 2.1 million cows, milk production would fall by 48.4 billion pounds, and retail milk prices would jump by about 90%—nearly double what shoppers were paying at the time. NMPF has been repeating those numbers for years in policy briefings because they’re hard to ignore.

So the question isn’t, “Does immigrant labor matter?” You already know it does. The real question is: in a world where enforcement risk is real, and the politics around this are volatile, what does a 200‑cow tie‑stall, a 500‑cow freestall, or a 1,500‑cow dry lot actually do next?

Let’s start with the ground we’re standing on.

Looking at This Trend: Dairy’s Economic Footprint and Who’s Turning the Wheels

Looking at this trend from the Wisconsin side, the numbers are big enough that they’re worth saying out loud. A 2024 update to Wisconsin’s dairy economic impact, produced by UW–Madison agricultural economists in partnership with the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection and highlighted by Dairy Farmers of Wisconsin and Hoard’s Dairyman, estimated that dairy—on‑farm and processing combined—now contributes about 52.8 billion dollars a year to the state’s economy, based on 2022 data. That same report said dairy supports roughly 120,700 jobs and accounts for about 45% of all agricultural activity in the state, a bump up from an earlier 45.6‑billion‑dollar, 157,000‑job impact that was widely reported in 2019.

You don’t really need a PDF to feel that in your town. You see it in the milk trucks on the road. You see it in cheese plants, with shifts added or cut. You see it in the nutritionist who stops by to help you steady butterfat performance in the high group, or the equipment tech who shows up on a Sunday morning when the parlor vacuum won’t hold. You see it when the school bus is still full, with farm kids on it.

Now lay that economic footprint next to the labor picture. The School for Workers survey—and follow‑up pieces like “As we move to 2025, let’s look at the numbers” and “How many undocumented people live and work in Wisconsin?”—puts the share of Wisconsin dairy work done by undocumented workers at around 70%, with more than 10,000 people in that category statewide. The researchers note that this labor is heavily concentrated in larger herds and that it’s structurally baked into how Wisconsin dairy operates. Nationally, that Texas A&M/NMPF study says immigrant workers make up just over half of all hired dairy labor and that immigrant‑reliant operations produce nearly four‑fifths of U.S. milk. In public statements, NMPF leaders have used those numbers to argue that a sudden loss of immigrant labor would cut total economic output tied to dairy by about 32.1 billion dollars and cost roughly 208,000 jobs when you combine on‑farm and off‑farm impacts.

I’ve noticed that when you sit down with producers—from Wisconsin to New York to Idaho—the reaction isn’t, “Wow, I had no idea.” It’s more like, “Yeah, that tracks.” The real tension kicks in when people start asking, “Okay, what does it actually look like on my place if that labor starts to disappear here, not just somewhere else?”

What Farmers Are Finding: The 500‑Cow Stress Test

So let’s walk through a scenario that a lot of you can see yourselves in, even if your own numbers are off by 50 cows either way.

Picture a 500‑cow freestall herd in central Wisconsin:

- Cows in sand‑bedded freestalls.

- Milking three times a day.

- Herd average is right around 80 pounds per cow.

- Shipping about 40,000 pounds per day—roughly 14.6 million pounds a year.

- Eight to ten full‑time employees plus family.

Those numbers line up with what UW–Madison Extension and several co‑op field reps use as pretty typical for a well‑managed freestall herd in that size range.

Now imagine that over 10 to 14 days, four of those ten employees stop coming.

In a lot of Wisconsin operations, the reasons aren’t hard to picture. Maybe a family member was arrested in an enforcement action. Maybe they don’t feel safe driving without a license, a problem Wisconsin farmworker advocates talk about constantly. Maybe they move to another state where they think enforcement might be softer. Reporting in 2024 and 2025 from Wisconsin Watch and The Fulcrum has already described dairy workers in this state disappearing from barns after immigration actions or policy changes, even when their specific farm wasn’t the one targeted.

So what happens on your place in the first month?

Week 1: The Schedule Quietly Starts to Drift

On paper, you still call it 3x milking—5:30 a.m., 1:30 p.m., 9:30 p.m. But with 40% fewer hands:

- Cows stand longer in the holding pen because groups move slower.

- Milkers start shaving a little off prep to keep things roughly on schedule.

- Parlor cleaning and between‑group sanitation get compressed without really meaning to.

By day two or three, that middle milking slides later into the afternoon. Fresh cow checks in that fragile transition period get shorter or more rushed. On the whiteboard, it’s still three times a day. In the cows’ reality, it’s starting to feel closer to 2½, with intervals stretched and inconsistent.

You probably know this already, but the data backs it up. University and extension work from Wisconsin, Penn State, Cornell, and others has shown over and over that moving from two‑times‑a‑day to three‑times‑a‑day milking often boosts production by 10–20% in Holstein herds, depending on genetics, nutrition, and the detail of milking procedures. Many Midwest producers who’ve shared their numbers at field days and in farm papers report gains right in that band.

So if you slide back toward a 2x reality under stress—even while you keep telling yourself you’re still 3x—it’s reasonable to expect something like a 5–15% drop in shipped milk, at least for a while. On our 500‑cow example, a 10% loss off 40,000 pounds is 4,000 pounds per day. At 20 dollars per hundredweight, that’s about 800 dollars per day, or 24,000 dollars a month. On a per‑cow basis, you’re looking at roughly 48 dollars per cow per month, or around 1.60 dollars per hundredweight during that period. And keep in mind that’s without yet factoring in lost premiums or penalties.

| Metric | Normal Operations | After 40% Labor Loss | Delta (Loss) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-time employees | 10 | 6 | -4 |

| Daily milk shipped (lbs) | 40,000 | 36,000 | -4,000 |

| Daily revenue @ $20/cwt | $8,000 | $7,200 | -$800 |

| Monthly revenue | $240,000 | $216,000 | -$24,000 |

| Revenue per cow per month | $480 | $432 | -$48 |

| Labor cost (estimated) | $30,000 | $36,000* | +$6,000 |

| Net impact per month | — | — | -$30,000 |

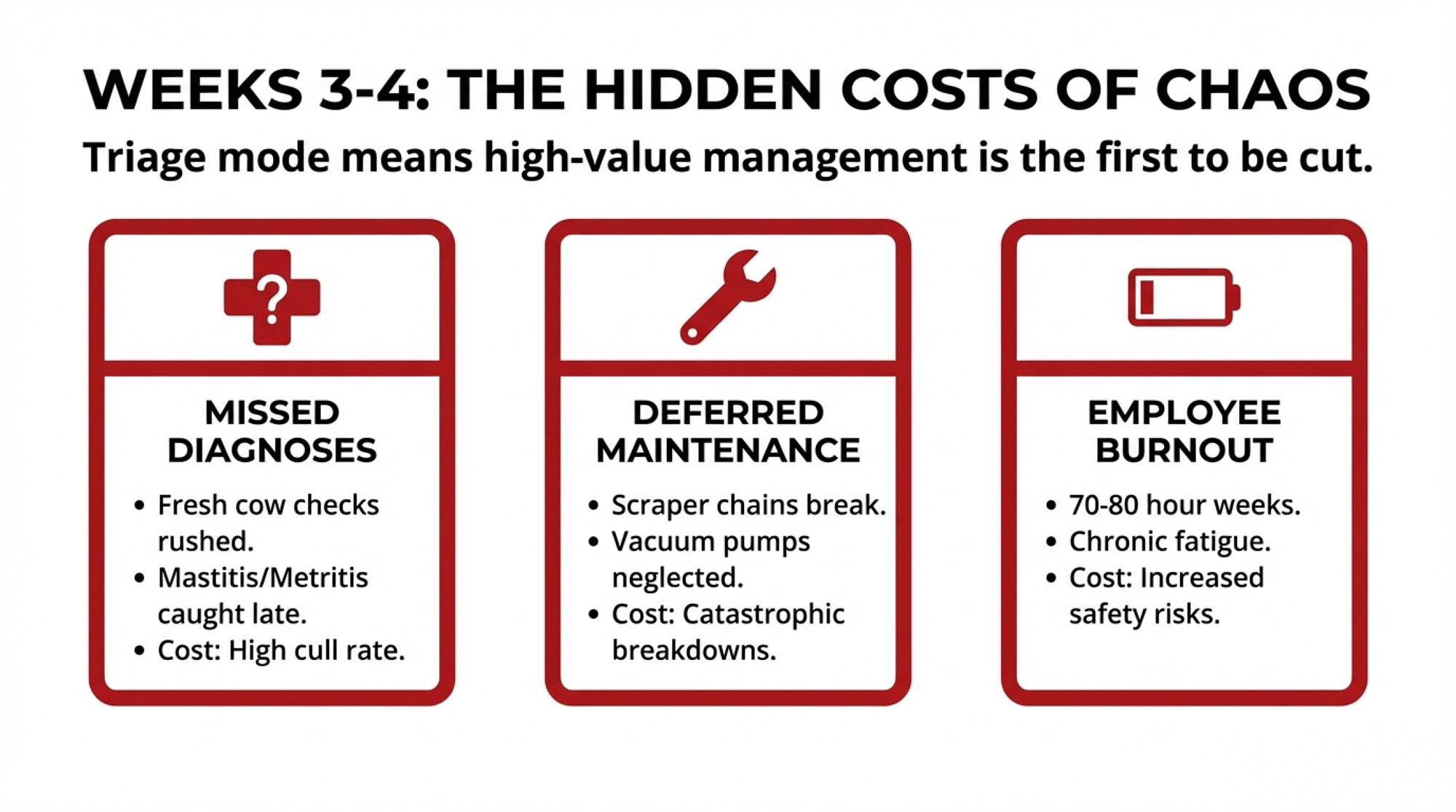

Weeks 2–3: Corners You Don’t Want to Cut Start Getting Cut

As the days go on, you and whoever’s left on the crew naturally triage. You know the unwritten order:

- Cows will be milked and fed.

- Calves will be fed.

- Everything else fights for the remaining time.

This is where some of the quiet, high‑value parts of good management start to take the hit—fresh cow management, calf health, and routine maintenance.

- Under normal staffing, somebody has the runway to walk the fresh pen and pick up little trouble signs: a quarter that’s just a touch warm, a cow that’s a bit slow to the bunk, a temperature that’s creeping. Veterinary work and herd health research are very clear: catching mastitis, metritis, or metabolic issues early is cheaper and more successful than catching them late. When you’re short on people, more of those cows get noticed when the problem is already full‑blown, with more drugs, more milk loss, and more culls.

- Calf programs that use tools like the Wisconsin Calf Health Scoring Chart, or similar systems from Penn State and UBC, depend on someone actually standing there and watching calves, not just dumping milk and moving on. Studies on calf pneumonia and growth show that early signs are easy to miss if you’re in a hurry. As many of us have seen, when labor is tight, more of those cases get picked up late, which means more treatment, more setbacks, and less consistent heifer performance.

- Maintenance that should be preventative becomes “we’ll get to it.” A scraper chain slapping in the gutter or a vacuum pump sounding a little off isn’t nothing. Farm management case studies from extension programs are full of stories where small maintenance jobs turned into big, expensive breakdowns because nobody had time to deal with them when they were still small.

And as a lot of you have experienced, this is exactly when butterfat performance can start to slide. Not because your nutritionist forgot how to balance a ration, but because feed push‑ups get less frequent, cows spend more time on concrete and less lying down, and the TMR might not be as consistent when the person who really knows that mixer is covering other jobs.

Week 4: Fatigue, Overtime, and Short‑Term Patches

By week four, people are tired.

- Those 50–60-hour weeks have become 70–80 hours without anyone formally deciding it.

- Family members who’d stepped back into more management roles are back on night checks and weekends.

- You’re juggling the barn, the books, and phone calls with lenders, advisers, and maybe an attorney.

Farm safety and occupational health teams have been warning for years that chronic fatigue raises the risk of accidents around livestock and machinery. Some of the most sobering farm injury stories shared in safety training events trace back to long weeks, short crews, and no slack.

On the cost side, overtime is now baked in. You might bring in a temp worker through an agency at a premium rate. Maybe a neighbor’s kids can help for a stretch. These patches can keep the wheels from coming completely off, but they rarely restore the level of consistency you had before the disruption.

So in roughly a month, you can end up with:

- Less milk shipped.

- Higher labor, vet, and repair bills.

- A herd and crew that are more stressed heading into the next cycle.

On a farm that was already operating close to break‑even, that kind of 30‑day hit can be what nudges you from “we’re getting by” into “we need a new plan.”

And that’s usually when H‑2A and robots start showing up in the same conversation.

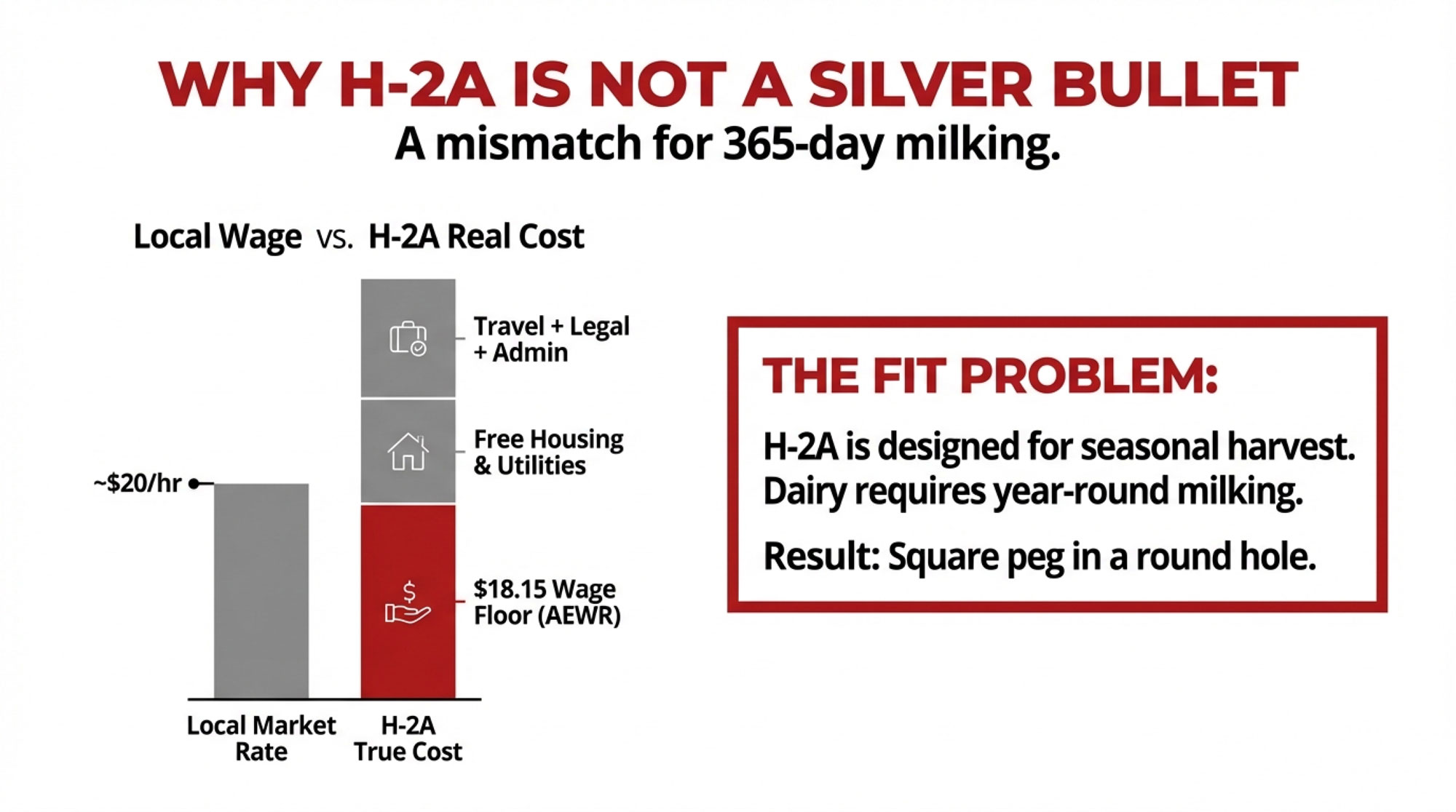

Looking at This Trend: Where H‑2A Helps—and Where It Doesn’t

Once you’ve walked through a scenario like that, someone almost always asks, “So what about H‑2A? Can’t we just use that to bring in legal workers?”

The H‑2A program, as the U.S. Department of Labor describes it and as farm labor attorneys explain it at grower meetings, is a temporary or seasonal agricultural worker visa. It’s built for jobs with clear start and end dates: apple harvest in New York, vegetable seasons in California and Arizona, planting and harvest windows on row‑crop farms in the Midwest. That’s where you see big H‑2A usage in the DOL statistics.

Milking in February in a Wisconsin freestall, or in July in an Idaho dry lot system, doesn’t have a natural “end.” It’s 365 days. Labor economists at Cornell and UW–Madison, as well as attorneys who specialize in ag and H‑2A compliance, have been telling dairy producers the same basic story: H‑2A can fit certain seasonal parts of dairy—corn silage harvest, fieldwork, some heifer raising, manure hauling—but it’s structurally awkward for year‑round milking jobs under current rules.

It’s worth noting the wage part, too. For 2025, the Department of Labor’s published Adverse Effect Wage Rate for H‑2A workers in Wisconsin is 18 dollars and 15 cents an hour. That’s the minimum you’re required to pay H‑2A workers and U.S. workers in the same roles if you’re using the program. Extension farm labor specialists and legal guides make that point very clearly.

But that 18.15 isn’t the whole cost. On top of that hourly wage, H‑2A employers must:

- Provide free housing that passes inspection and meets specific standards.

- Pay inbound and outbound travel once workers complete a required portion of the contract.

- Cover in‑country transportation related to the job.

- Recruit and consider domestic workers first, documenting those efforts.

- Keep detailed records and be ready for audits on wages, housing, and recruitment.

Labor attorneys and H‑2A consultants who work across dairy and row crops consistently tell clients that once you add housing, utilities, travel, legal fees, workers’ compensation, and administrative time, the real per‑hour cost of H‑2A labor typically lands well above the posted AEWR.

| Cost Category | Advertised/Visible | Actual Total Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Base hourly wage | $18.15/hr (WI 2025 AEWR) | $18.15/hr |

| Housing (construction/rent) | “Provided” | +$2.50–4.00/hr |

| Inbound/outbound travel | “Reimbursed” | +$0.75–1.50/hr |

| In-country transportation | “Covered” | +$0.50–1.00/hr |

| Recruitment & advertising | “Required” | +$0.50–1.25/hr |

| Legal & administrative | “Standard” | +$1.00–2.00/hr |

| Workers’ comp (incremental) | Included in payroll | +$0.25–0.75/hr |

| Audit/compliance risk | Not discussed | +$0.50–1.00/hr |

| Total effective hourly cost | $18.15/hr | $24.00–30.00/hr |

So what farmers are finding is that H‑2A can be a useful part of the picture, particularly for cropping and some support work. But it isn’t a simple plug‑and‑play replacement for the undocumented workforce in a 24/7 parlor. Dairy isn’t legally excluded from H‑2A, but in practice, it’s hard to fit full‑time milking jobs into a program designed for seasonal work.

And like we said earlier, neither H‑2A nor robots are magic wands. Anyone telling you different probably won’t be the one standing beside you when something breaks.

What Farmers Are Finding Next: Two Main Strategic Paths

So if enforcement risk is up, a big chunk of your crew is legally vulnerable, and H‑2A is only a partial answer, where does that leave a 500‑cow Wisconsin dairy? Or a 250‑cow Ontario freestall? Or a 1,600‑cow Idaho dry lot?

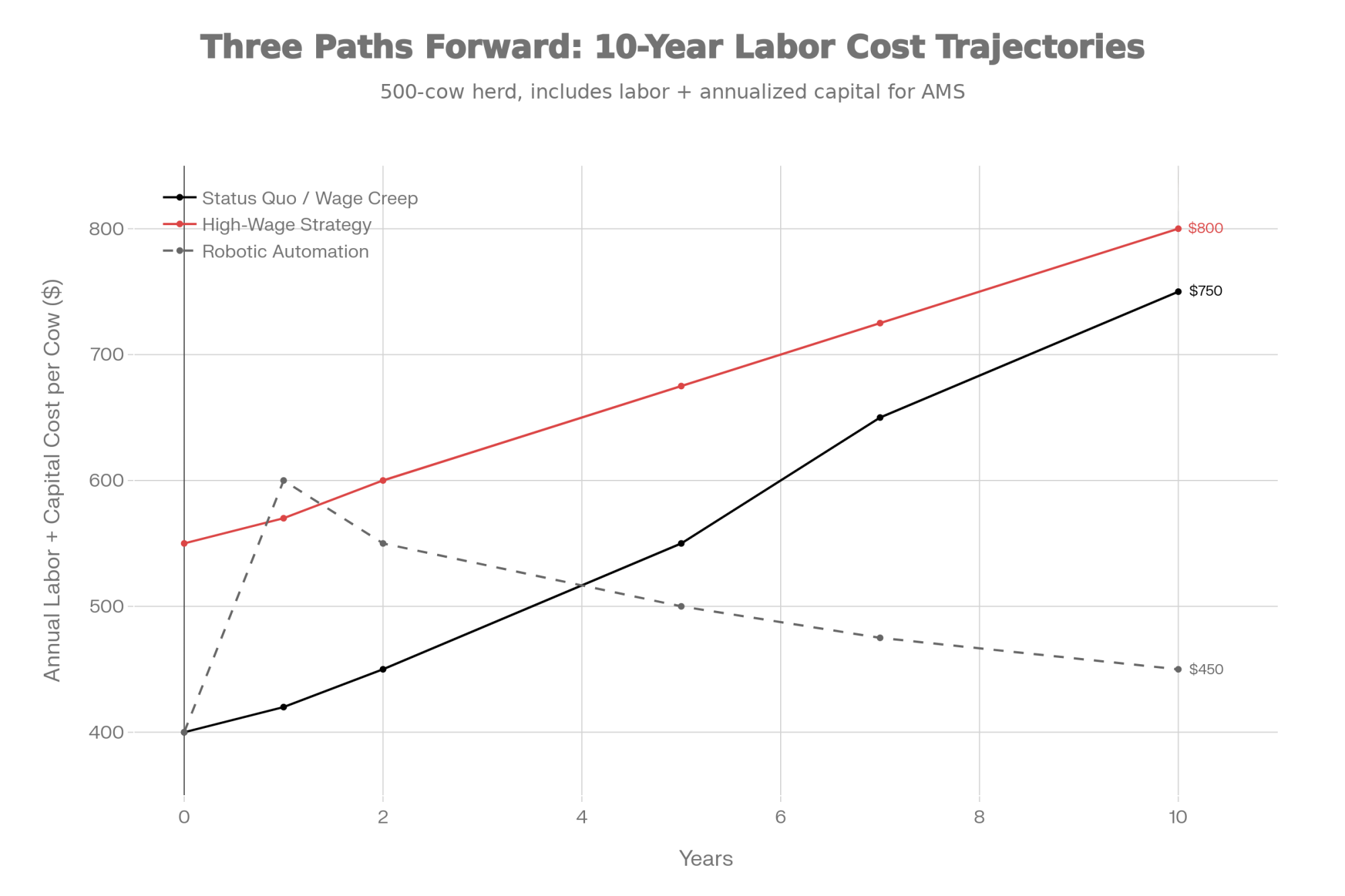

What I’ve noticed, listening to producer panels, lender roundtables, and extension meetings in different regions, is that most serious operations are circling around two main strategies—often mixing elements of both:

- Pay more and build a stronger, more legal people system.

- Invest in automation—especially robotic milking—to permanently change the labor equation.

Let’s walk through those one at a time.

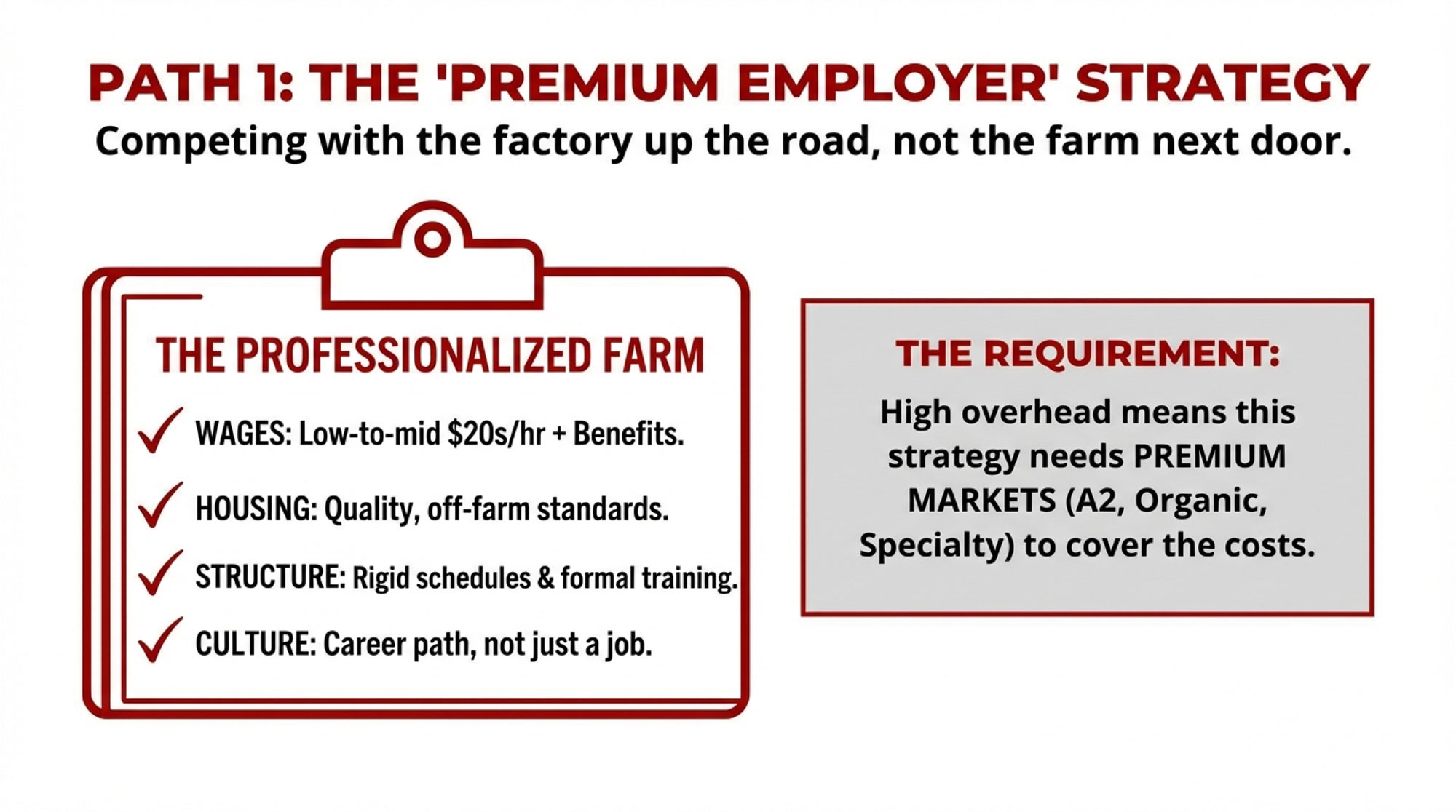

Path 1: Paying More and Building a Stronger People System

In Wisconsin herds, and honestly across much of the Midwest and Northeast, you’re not just bidding against other barns. You’re competing with warehouses, food processors, manufacturing plants, construction crews, and trucking companies. Rural labor market reports and USDA summaries show that non‑farm employers are offering starting wages in the low‑ to mid-20-dollar-per-hour range, plus overtime and some benefits.

Many Midwest producers report that, to attract U.S.-born or fully documented workers, they’ve had to offer wages and schedules that look a lot more like those at the plant up the road. When you layer in payroll taxes and basic benefits, it’s easy to see how labor costs on a 500‑cow herd can step from, say, the mid‑300,000 dollar range into the upper six figures if more positions are filled at those higher total hourly costs.

What’s interesting is that on farms where this actually works, it’s almost never “we just pay more and hope.” A few patterns show up over and over in case studies and interviews:

- Housing improves—whether that’s on‑farm housing brought up to a decent standard or stipends that let people live in town.

- Schedules get more predictable, with real days off and clearer expectations about nights and weekends.

- Training and protocols become more structured, especially in sensitive areas such as fresh cow management, transition period monitoring, TMR mixing, cow handling, and calf care.

- Owners spend more time on communication and culture because losing a solid worker now costs much more financially.

Extension farm business programs and progressive dairy profiles have highlighted that farms who treat labor as a central asset—not just a line item—often see more stable teams and, over time, smoother herd performance: lower somatic cell counts, better repro, fewer train wrecks in the fresh pen.

This “high‑wage, high‑support” model tends to hold together best when:

- You’ve got access to some kind of premium—organic, grass‑fed, A2, specialty cheese contracts—that keep your mailbox price high enough to carry those wages.

- Your fixed costs are under control because the major barn and parlor debt has already been paid down.

- Family is still closely involved in key areas, especially maternity, fresh cows, and calves.

On smaller farms—say that 100–200 cow band—in Wisconsin, Ontario, New York, and elsewhere, this path often looks a bit different. Some herds lean into on‑farm processing, direct marketing, or local niche contracts to support a small, well‑paid core team. Others, after sitting down with their numbers and the next generation, choose to plan an exit from milking while equity is solid and physical and mental health are still in good shape, pivoting into cropping, custom work, or contract raising.

The trade‑off here is pretty straightforward: you’re more exposed to wage competition and less to big capital swings. If a new distribution center or plant opens nearby with a slightly better package, you may find yourself revisiting wages and schedules sooner than you’d like.

Path 2: Robotic Milking as Long‑Term Labor Risk Management

The other path, as many of us have seen in northeast Wisconsin, New York, Quebec, and parts of Europe, is to lean into automation—especially robotic milking systems.

The nice thing is we’re not guessing purely from brochures anymore. UW–Madison Extension, along with other university and industry partners, has studied real AMS herds and found that, on average, farms adopting automated milking are cutting labor time per cow by roughly a third and labor per hundredweight by 35–40% compared to their previous systems. That lines up with what researchers and producers in Canada and Europe report as well: robots don’t eliminate labor, but they often significantly reduce total labor per unit of milk.

Producers who’ve made the switch and shared their experiences at meetings and in farm media tend to point to three big shifts:

- They need fewer total people to milk the same number of cows—or in some cases, a few more cows.

- The mix of work changes; there’s more focus on watching cows, managing fresh cows and the transition period, keeping robots maintained, and making sense of data, and less time just standing in a pit attaching units.

- Their day is organized more around checking robot data and dealing with exceptions than around fixed milking shifts.

Some herds that moved from 2x parlor milking to voluntary milking with robots have reported modest increases in milk per cow—often in that two‑pounds‑per‑day kind of range—when cow flow and feed management are right. AMS planning tools from extension and consultants generally treat those gains as possible, but not automatic, which is the right level of caution.

Of course, those robots and all the concrete and steel around them are a serious investment. AMS case studies from Wisconsin, New York, and Western states show that 500–800 cow conversions often land in the low‑ to mid‑seven‑figure range once you add robots, gate work, new concrete, electrical, and vacuum upgrades, and so on. Spread over a decade or so, that often works out to an annual capital cost per cow in the low‑ to mid‑hundreds of dollars, depending on interest rates, any production bump, and the mix of retrofit versus new build.

So why are so many herds, including some mid‑sized family farms, taking that path? Because when they run 10‑year cash flows with their advisers, they’re not comparing robots to a world where good milkers are easy to find at 14 dollars an hour. They’re comparing robots to a world where:

- Their current undocumented workforce may not be there in five years.

- H‑2A might help in the fields, but not much in the parlor.

- Local wages are being pulled upward by non‑farm employers.

This development suggests that shifting some of the risk from variable labor costs to more predictable capital and maintenance costs sometimes looks less like a luxury and more like buying insurance. You still need good people, but fewer, and the core job of milking is less exposed to the next policy swing or enforcement wave.

From what AMS specialists, lenders, and robot users are saying publicly, this path tends to make the most sense when:

- Your barn layout either already fits robot traffic or can be redesigned without blowing the budget.

- You’ve got access to capital and a lender who understands AMS technology and your management record.

- There’s a next generation—or at least someone on the team—who’s comfortable managing technology and data.

It’s not a cure‑all. Robots come with their own brand of stress. But they’re increasingly a serious part of the dairy labor conversation, not just a novelty.

Looking Beyond the Lane: How Labor Decisions Ripple Through the Dairy Chain

It’s easy to focus only on your own driveway. But, as that Texas A&M/NMPF modelling made clear, labor shocks don’t stop at the barn door.

When those economists modelled a total loss of immigrant labor on dairy farms, they didn’t just stop at counting cows and pounds of milk. Using national economic modelling tools, they estimated that total economic output tied to dairy would drop by about 32.1 billion dollars and that the U.S. would see roughly 208,000 fewer jobs—around 77,000 on farms and another 131,000 in processing, transport, input supply, and related services.

In Wisconsin, where the updated UW–Madison/DATCP numbers put dairy’s impact at 52.8 billion dollars and 120,700 jobs, you don’t need to be a PhD to see how fragile the chain can be. If labor issues push a noticeable chunk of herds to shrink or exit, that flows through to co‑op plant utilization, cheese plant expansions, feed mills, equipment dealers, and town businesses.

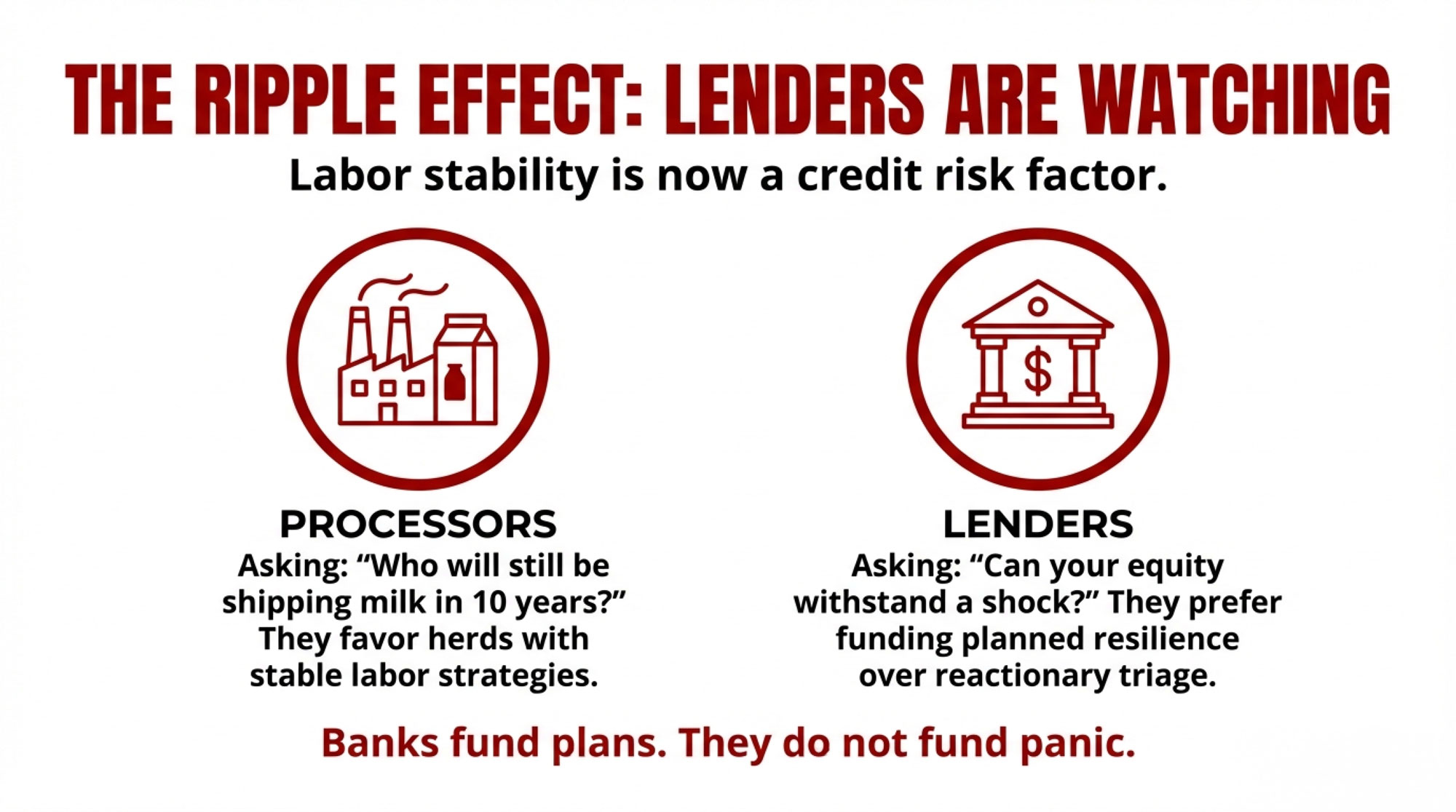

I’ve noticed that processors and co‑ops, in industry panels and trade press interviews, are increasingly frank that they’re paying attention to farm labor stability when they think about long‑term milk supply. They’re not only asking, “Who has milk today?” but also, “Who is likely to still be shipping consistently in five or ten years in a tighter labor environment?”

It doesn’t mean you’re responsible for solving the whole system. But it does mean your labor strategy is part of how lenders, buyers, and even neighbors look at your farm’s long‑term resilience.

Turning Worry into a Plan: Questions to Take Back to the Farm

So, where does all of this really leave you, at your own kitchen table?

What I’ve found is that the farms handling this moment best aren’t necessarily the biggest or the fanciest. They’re the ones who’ve taken that background worry about labor and turned it into a set of concrete questions. Here are a few that have led to useful conversations on real farms.

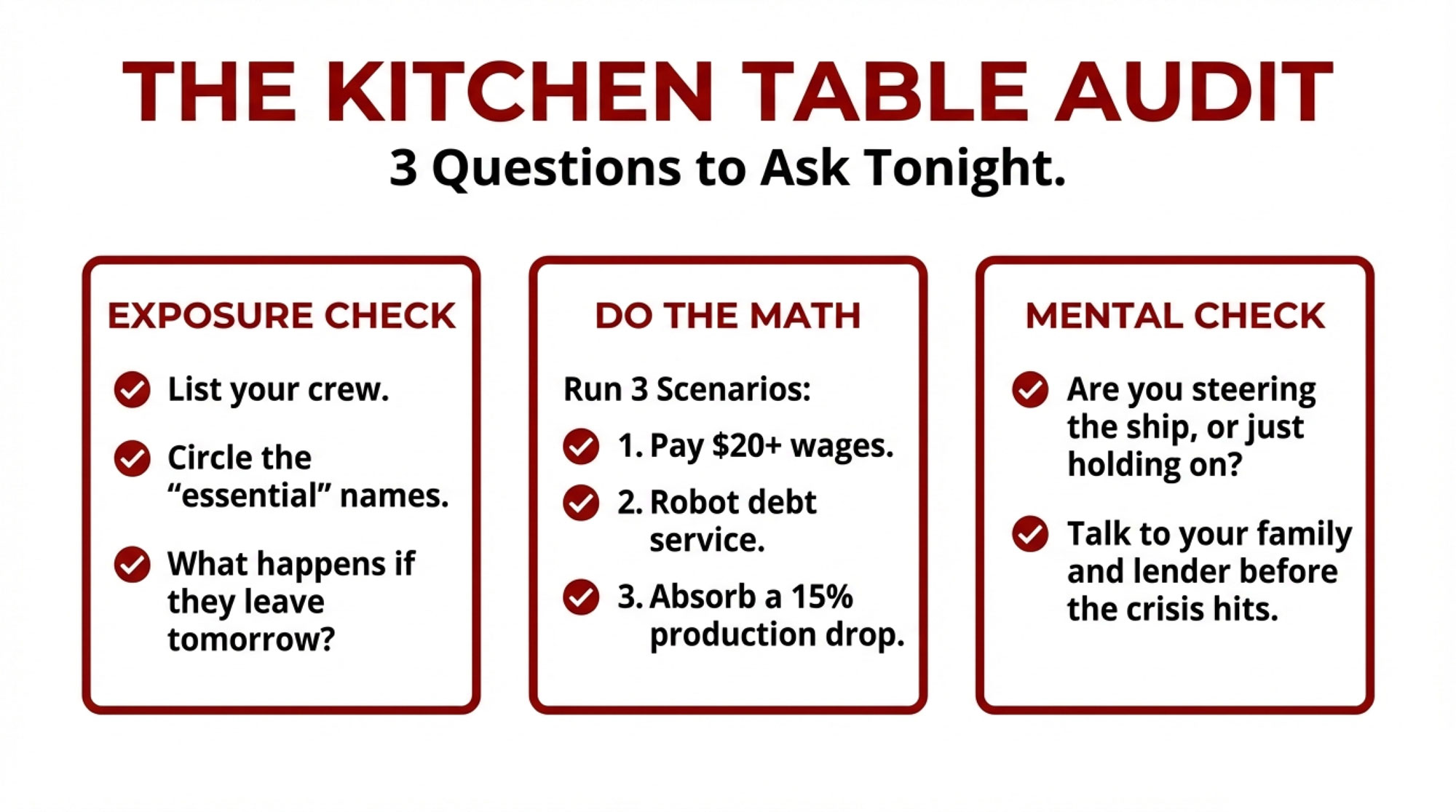

1. Where Are You Most Exposed on Labor?

Start with a simple exercise that a lot of us put off:

- List every employee and what they actually do day‑to‑day.

- Note who’s cross‑trained and who’s the only one who really knows a particular job.

- Circle your “if they left tomorrow, we’d be in trouble” people—the one who really understands your fresh cow pen, the one who can keep the mixer and tractors running, the one who quietly keeps order in the parlor.

Then ask yourself:

- If 30–40% of this crew disappeared, what would we change first?

- Would we drop from 3x to 2x milking?

- Would our calf program slide from “very good” to “it gets done”?

- Would fresh cow checks and transition period monitoring get squeezed to the margins?

- Would maintenance go from “scheduled” to “when it breaks”?

You probably already know the honest answers. Putting them in writing just makes them harder to dodge.

2. What Do Your Numbers Look Like Under Different Labor Realities?

Next, move from gut feeling to actual numbers.

Sit down with your accountant, a farm business consultant, or an extension specialist and sketch out at least three scenarios:

- A higher‑wage scenario where you pay enough to compete with non‑farm jobs and try to build a more legal, stable crew.

- A labor shock scenario where you drop, say, 10–15% in milk for several months and see overtime and temp labor bills jump.

- An automation scenario where you invest in AMS or other labor‑saving technology and shift some of your cost burden from wages to capital and maintenance.

For each one, look at:

- Your break‑even milk price per hundredweight.

- Cash flow over the next 12–24 months.

- How long can your current equity and debt structure withstand that level of stress?

You don’t have to decide the same day. But once you see those lines on paper, some options will feel more realistic and others less so.

3. What Would Automation Actually Look Like on Your Farm?

If you’ve ever said, “We should at least get a quote on robots,” this might be the year actually to do it.

- Ask one or two AMS companies you trust to walk your barns and talk through cow flow, stall layout, and utilities.

- Get full‑project estimates—robots, sort gates, concrete, electrical, service contracts, the whole package.

- Ask for hard numbers from herds that look like yours in size and climate: labor hours per cow before and after, milk per cow, health events, and repair costs.

Then stack that AMS scenario alongside your higher‑wage and labor shock scenarios. You’re not committing by asking questions. You’re just giving yourself a clearer sense of what “more steel, fewer people” really means in dollars and in daily work.

4. How Does Your Lender See the Road Ahead?

Lenders who focus on dairy are following the same School for Workers updates, Texas A&M modelling, and DOL wage tables that you are. Many have their own quiet models about labor risk.

Good questions to ask include:

- How do you see dairy in this region over the next 5–10 years, given labor and policy trends?

- Are you open to financing well‑planned wage or automation strategies that clearly reduce long‑term labor risk?

- If we get squeezed mainly by labor issues, not just milk price, what options would realistically be on the table—interest‑only periods, restructuring, or something else?

Some farm credit and bank reps have been pretty upfront in recent meetings that they prefer working with operations that think ahead rather than just react to the next crisis. That’s worth knowing sooner rather than later.

5. How Are You and Your Family Holding Up?

And then there’s the part we tend to talk about last—how all of this feels.

Analyses of occupational suicide risk that have been discussed by the University of Iowa’s public health team and farm mental health advocates point out that farmers and ranchers, in some time periods, have had suicide rates several times higher than the general population. Some summaries cite ratios in the ballpark of three‑and‑a‑half times higher during certain decades. Nobody in this business really needs a statistic to know the load is heavy—but the numbers are a reminder that it’s not just you.

Layer labor uncertainty on top of milk price swings, feed bills, and family succession, and it adds weight, not relief. Mental health professionals who work with farm families, along with farmer‑to‑farmer support initiatives, often say that having even a rough plan—not just hoping—can take a little pressure off. It doesn’t fix everything, but it helps you feel like you’re steering, not just riding.

So it’s worth asking:

- Have we sat down, as a family, and talked about what we really want this farm to look like in 5–10 years?

- Do I have one or two people—spouse, neighbor, another producer, pastor, counselor—I can be completely honest with when I’m at the end of my rope?

- Am I giving myself even a fraction of the attention and care I give to my fresh cows in the transition period?

You know as well as anyone that ignoring problems in the fresh pen doesn’t make them go away. Same idea here.

The Bottom Line

If we were topping up the coffee and wrapping up, here’s what I’d leave on the table.

First, labor isn’t just a nagging headache anymore. Between the School for Workers’ 70% number, the Texas A&M/NMPF modelling, the 52.8‑billion‑dollar Wisconsin impact report, and what you see when you try to hire, the message is pretty clear: who’s in your parlor, what status they have, what you pay them and how replaceable they are have become strategic decisions, right alongside feed cost and debt structure.

Second, the industry is slowly drifting into a shape where:

- A smaller number of larger, often more automated herds account for a large share of the commodity milk supply.

- A smaller group of premium‑focused dairies use higher prices to support higher wages and service levels.

- Mid‑sized, conventional herds that lean heavily on vulnerable labor and thin margins feel the most squeeze.

Third—and this is the part I find encouraging—your path isn’t decided for you. I’ve seen farms in all of those “lanes” make deliberate, thoughtful moves:

- Some have said, “We’re going to be one of the best employers in this county,” and backed it up with wages, housing, and schedules.

- Some have said, “We’re going to bet on tech,” and built robot barns or added other automation to change their labor equation.

- Some, especially in that 100–200 cow range, have decided to lean into niche markets or to plan an exit while equity is still solid and health and relationships are still good.

If you boil it down to a short list of next moves, it might look like this:

- Be honest about where you’re most exposed on labor.

- Run the numbers on higher wages, labor shocks, and automation, rather than guessing.

- Talk with your lender and your family before the next crisis, not after.

- Choose a path—top‑tier employer, tech adopter, niche player, or planned exit—while you still have options.

| Farm Characteristic | High-Wage / People Path | Robotic / Tech Path | Niche / Exit Path |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current herd size | 200–600 cows ✓ | 400–800 cows ✓ | 50–250 cows ✓ |

| Milk price / premium | Organic, A2, grass-fed, or specialty contract ✓ | Commodity or stable co-op ✓ | Direct retail or local processor ✓ |

| Debt structure | Low debt, strong equity ✓ | Access to capital, lender confident in AMS ✓ | Minimal debt critical |

| Next generation status | Committed successor in place ✓ | Tech-savvy successor or manager ✓ | No clear successor |

| Labor market competition | Can outbid non-farm wages ✓ | Struggling to find/keep any crew ✓ | Very tight local market |

| Risk tolerance | Moderate; can handle wage volatility | High; comfortable with capital risk | Low; exit while equity is strong |

| Best first step | Benchmark wages vs. local jobs; upgrade housing | Get 2–3 AMS quotes; tour similar herds | Talk to lender about transition timeline; map equity options |

Don’t wait for labor to “go back to normal.” It probably won’t. What you can do is build a strategy around the labor reality you’re actually in.

And like we tell our kids—and our fresh cows—it’s easier to get through a tough stretch when you’re not going into it alone and without a plan.

Key Takeaways:

- 70% on shaky ground: UW–Madison’s School for Workers found more than 10,000 undocumented workers perform about 70% of Wisconsin’s dairy labor—without them, researchers say the industry would “collapse overnight.”

- National stakes are massive: Texas A&M/NMPF data shows immigrant workers make up 51% of hired U.S. dairy labor and produce 79% of milk; losing them would close 7,000+ farms, cut 48.4 billion pounds of production, and nearly double retail prices.

- 30 days, 40% gone, $24k lost: When a 500‑cow herd loses 40% of its crew, milking intervals stretch, fresh cow management slips, butterfat drops, and overtime piles up—roughly $24,000 in lost milk in one month alone.

- H‑2A helps, but doesn’t fix the parlor: The visa fits seasonal crop work, not year‑round milking; real costs run well above the $18.15/hr AEWR once housing, travel, and compliance are included.

- Two paths, one decision window: Compete for legal labor with wages in the 20s plus better housing and schedules, or invest in robotic milking to cut labor per hundredweight by 35–40%. Farms running the scenarios and talking to lenders now are choosing their own future—not having it forced on them later.

Learn More

- The Hidden Costs of Turnover: Why Your Dairy’s Biggest Crisis Isn’t What You Think – Gain a clear method to stop the $15,000-per-worker drain on your bottom line with this audit of workforce instability. This breakdown armours you with management tactics to cut turnover by 30% and protect your production from silent leaks.

- 2025’s $21 Milk Reality: The 18-Month Window to Transform Your Dairy Before Consolidation Decides for You – Exposes the structural shifts transforming 35,000 farms into three distinct 2030 models. This strategic forecast delivers a roadmap for mid-size survival, positioning your operation to capture premiums and leverage scale before market consolidation moves against you.

- Dairy Tech ROI: The Questions That Separate $50K Wins from $200K Mistakes – Master the hard math of technology adoption by identifying why robots require a $27.05 per hour labor threshold to break even. This analysis armours your capital planning with scale-specific implementation guides that deliver a minimum 15% annual return.