51 sick babies and 55 organic farms show how one powder plant can flip your dairy’s risk, premiums, and lender conversations overnight.

Executive Summary: The ByHeart infant botulism outbreak—51 hospitalized babies in 19 states tied to powdered formula—has turned one organic whole milk powder chain into a live stress test for dairy contracts and supply‑chain risk. At the center are 55 organic farms shipping to Organic West, DFA’s Fallon, Nevada plant drying that milk into organic whole milk powder, and ByHeart’s premium “clean label” formula that used the powder before FDA testing found botulinum toxin in both sealed cans and the ingredient. With the investigation still open and the FDA already tightening oversight of the infant formula sector following earlier recalls and shortages, any producer whose milk ends up in infant formula or other products now has to assume more scrutiny, not less. The article walks through the outbreak timeline and the science of spores that can survive standard milk processing, then translates that into four practical ripple effects on the farm: tougher quality expectations, tighter traceability, more complex recall and indemnity risk, and sharper scrutiny of organic and “clean label” claims. It closes with a clear playbook for progressive dairies—measure how much of your milk flows into powder and infant channels, pull three to five years of quality and audit records into one place, reread contracts with recall liability in mind, sit down with your insurer about contamination and business‑interruption coverage, and decide how much exposure to infant markets fits your long‑term margin and survival strategy.

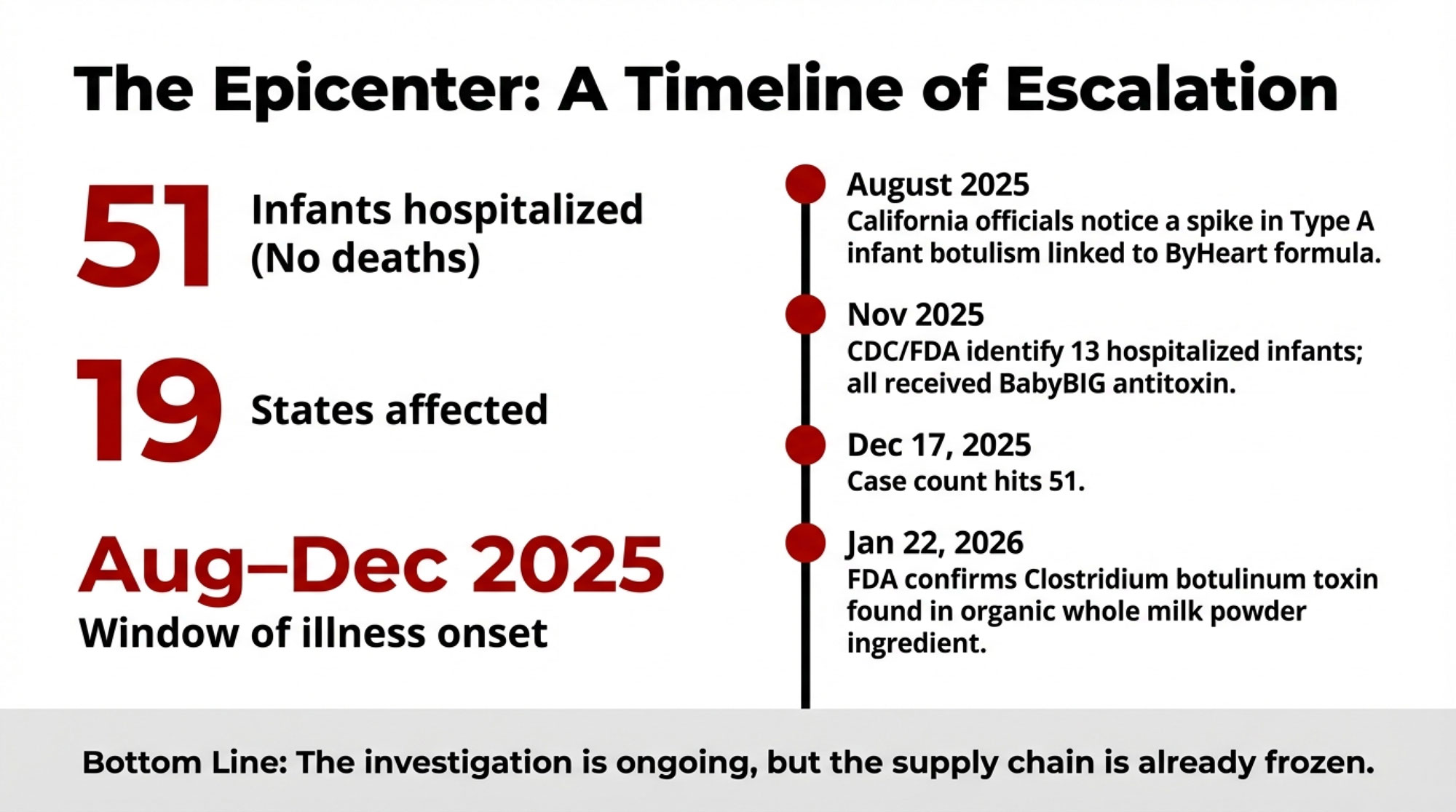

Fifty‑one hospitalized babies tied to an infant formula outbreak have just changed how every one of us should think about milk heading into a powder plant. In late 2025, FDA and CDC investigators connected this infant botulism cluster—51 infants in 19 states, all hospitalized, with no deaths reported as of mid‑December—to ByHeart’s powdered infant formula. Regulators then traced the problem back to an organic whole milk powder ingredient used in that formula, which is where dairy producers like us suddenly get pulled into the story.

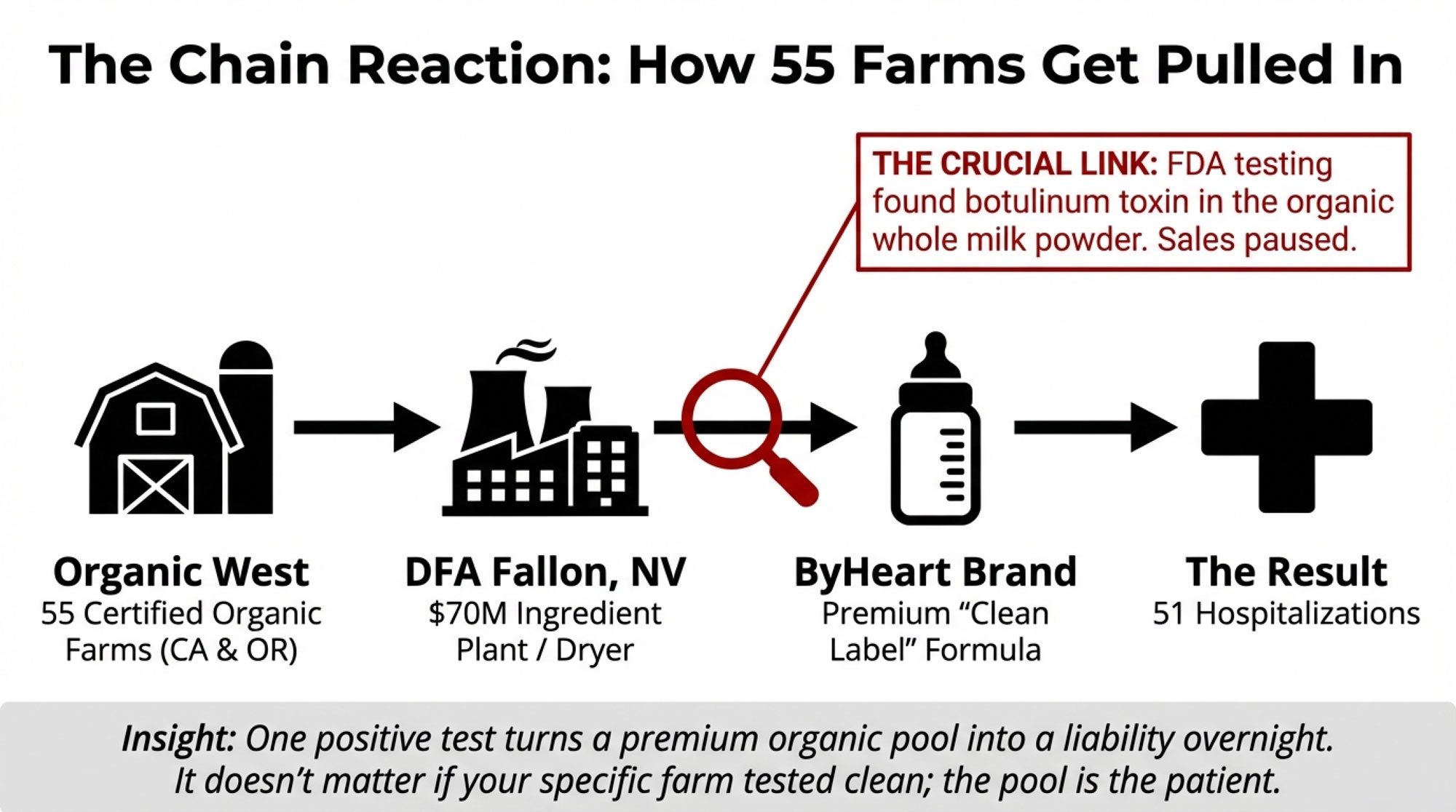

This isn’t some theoretical scenario. It’s a real supply chain made up of 55 organic farms, an ingredient plant in Nevada, and a premium “clean label” formula brand that, on paper, looked like one of the safest systems out there.

How a “Clean” Infant Formula Ended Up at the Center of an Outbreak

Let’s start with what’s on solid ground. By mid‑December 2025, federal and pediatric sources reported 51 suspected or confirmed infant botulism cases across 19 states, all involving babies who’d consumed ByHeart Whole Nutrition infant formula. Every one of those infants was hospitalized, but no deaths had been reported at that point.

ByHeart isn’t a bargain‑bin product. It’s a U.S. infant nutrition company that came to market with a lot of fanfare: “from scratch” formulation, organic grass‑fed whole milk, no corn syrup, no maltodextrin, no soy or palm oil. Clean Label Project awarded ByHeart its Purity Award and later its “First 1,000 Day Promise” certification for testing against hundreds of contaminants. That’s the kind of branding you and I see and think, “Okay, they’re serious about safety.”

On the ingredient side, you’ve got Organic West Milk Inc. Co‑owner Bill Van Ryn has said his company collects milk from 55 certified organic dairies, mainly in California, and that this milk is processed into organic whole milk powder. That powder, in turn, is produced at Dairy Farmers of America’s ingredient plant in Fallon, Nevada. When the plant was built, local reporting pegged it at roughly a 70‑million‑dollar project, designed to handle around 2 million pounds of milk a day and produce in the neighborhood of 250,000 pounds of powder and other dried ingredients daily.

Van Ryn has also been clear on two key points. First, Organic West hasn’t supplied organic whole milk powder to any infant formula manufacturer other than ByHeart. Second, after FDA testing found Clostridium botulinum in a sample of their powder, they paused sales of powder for products used in infant and children’s foods while the investigation runs its course.

At the same time, FDA testing found the same type of botulinum toxin in sealed cans of ByHeart formula and in infants’ stool samples. So regulators know the spores are somewhere in that system. As of late January 2026, though, they haven’t pinned down exactly where the contamination entered—on farm, in the powder plant, at the blending step, or somewhere further downstream.

It’s worth noting that the CDC and FDA don’t call something an outbreak lightly. Infant botulism is rare, and having this many cases associated with a commercial formula is extremely unusual. Guidance from CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics has long noted that spores are widespread in soil and dust and that infants under one year are more vulnerable because their gut and microbiome aren’t fully mature. The basic message is simple: spores and infant foods don’t mix.

The Timeline: August to December, 51 Infants in 19 States

The way this rolled out will feel familiar if you’ve watched other food safety issues, just with higher stakes.

In August 2025, California’s Infant Botulism Treatment and Prevention Program started seeing more Type A infant botulism cases than usual. The common thread they noticed was the consumption of ByHeart powdered formula. That triggered further investigation.

By early November, CDC and FDA had identified 13 infants in 10 states who’d been hospitalized with suspected or confirmed infant botulism and had received BabyBIG antitoxin. All of those babies had a history of consuming ByHeart formula. As more cases came in, FDA’s public updates ticked up to 39 cases by early December—spread across 18 states, with ages ranging from just a few weeks to about 8 or 9 months, and illness onset between early August and late November.

By December 17, 2025, the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Red Book online summary had the number at 51 infants in 19 states, all with suspected or confirmed infant botulism and all linked to ByHeart formula exposure. Through all of that, the headline stayed the same: hospitalized, no deaths.

So when the FDA released an update on January 22, 2026, saying they had identified organic whole milk powder as the ingredient associated with the outbreak—and that testing had found botulinum toxin in that powder—that’s when the dairy side of the supply chain landed squarely in the frame. For the 55 farms shipping through Organic West, and for anyone with milk flowing into infant formula powder plants, this stopped being “someone else’s problem.”

What the Science Says About Spores, Heat, and Why This Matters to Dairies

You probably know the basics, but it helps to pull it together.

With infant botulism, babies aren’t usually ingesting pre‑formed toxin. Instead, they ingest spores, which then germinate and produce toxin in the gut. Older children and adults can often ingest spores without symptoms because their gut environment is more mature and resistant to colonization.

The problem for us on the milk side is that Clostridium botulinum spores are built to survive. Scientific work and public‑health guidance agree: spores are highly heat‑resistant. Standard milk pasteurization and typical spray‑drying conditions do not reliably destroy them. It takes more severe treatments—like those used for shelf‑stable canned foods—to inactivate spores consistently, and that’s not how we process fluid milk or most powders.

| Pathogen or Spore | Standard Milk Pasteurization (161°F, 15 sec) | Spray-Drying (160–200°F typical) | What It Actually Takes to Kill | Present in ByHeart Outbreak? |

| Salmonella | ✓ Killed | ✓ Killed | 161°F+ for 15 sec | No—destroyed by pasteurization |

| Listeria | ✓ Killed | ✓ Killed | 161°F+ for 15 sec | No—destroyed by pasteurization |

| Cronobacter | ✓ Killed | ✓ Killed | 161°F+ for 15 sec | No—destroyed by pasteurization |

| E. coli O157:H7 | ✓ Killed | ✓ Killed | 155°F+ for 15 sec | No—destroyed by pasteurization |

| Clostridium botulinum SPORES | ✗ SURVIVES | ✗ SURVIVES | 250°F+ for 3+ min (pressure canning) | YES—found in powder & sealed cans |

| Bacillus cereus spores | ✗ Survives | ✗ Survives | 250°F+ for extended time | Not reported |

Historically, most infant botulism cases have been linked to environmental exposure and honey, not commercial formula. So the track record for the formula has been quite good. But when you look at the FDA’s published focus on powdered formula safety, it has leaned heavily on organisms such as Cronobacter and Salmonella. This outbreak is a hard reminder that spores are a different challenge. They don’t behave like standard bacteria, and they can ride along in dust, soil, and dried residues in ways that are easy to underestimate.

For farms shipping to ingredient plants serving infant markets, that matters. It’s not just about plate counts, fresh cow management, and keeping butterfat levels where they need to be. It’s also about whether your milk and your plant’s environment are being managed with spore risk in mind, even if the odds of a problem are low.

Mapping the Chain: From Organic Herds to Fallon

Let’s walk through the supply chain as credible reporting has laid it out.

On the farm end, 55 certified organic dairies ship to Organic West. Many of these are in California’s main organic regions, with at least some milk coming in from outside the state, such as Oregon. These are full‑time commercial herds, not hobby operations. They’ve gone through organic certification, pasture requirements, and the paperwork that comes with chasing organic premiums rather than just taking a basic blend price.

Organic West then moves that milk into DFA’s Fallon ingredient plant in Nevada. That facility was promoted as a major anchor for regional dairy when it was built. Contemporary coverage described roughly $70 million in capital investment, the capacity to handle about 2 million pounds of milk per day, and finished output of about a quarter‑million pounds of powder and other dried ingredients per day. Economic development folks projected that the area herd would need to grow significantly to feed the plant, and that the regional dairy sector could see a sizable boost as the plant ramped up.

From Fallon, the organic whole milk powder goes out as an ingredient. In ByHeart’s case, they use that powder at blending and packaging facilities in multiple states to make finished infant formula. That formula is then sold nationwide. That’s how a problem at the ingredient level can end up with 51 sick babies across 19 states: one product, one brand, lots of distribution.

| Supply-Chain Stage | Entity | Volume/Scale | Contamination Entry Risk | Who Controls Quality Here? | Your Farm’s Visibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Farm | 55 certified organic dairies (CA, OR) | Unknown total volume | Soil, dust, feed, environment | Individual farm protocols | HIGH |

| 2. Collection | Organic West Milk Inc. (Bill Van Ryn) | Pooled multi-farm milk | Tanker hygiene, cross-contamination | Hauler + farm coordination | MEDIUM |

| 3. Processing | DFA Fallon, NV ingredient plant | ~2M lbs milk/day → ~250K lbs powder/day | Plant environment, dryer surfaces, packaging | DFA plant SOPs + FDA oversight | LOW |

| 4. Ingredient Supply | Organic West powder to ByHeart | Unknown tonnage to infant formula only | Warehouse storage, handling, moisture | Ingredient supplier + buyer specs | VERY LOW |

| 5. Formula Blending | ByHeart facilities (multiple states) | National distribution scale | Blending equipment, other ingredients | ByHeart manufacturing SOPs | NONE |

| 6. Retail/Consumer | Nationwide (19 states affected) | 51 hospitalized infants (Dec 2025) | Post-production handling (rare for spores) | Retailers + consumer storage | NONE |

FDA’s public position is careful but clear. They’ve reported that organic whole milk powder used in ByHeart formula tested positive for botulinum toxin, and that they believe the ingredient supplier is likely where contamination entered the chain. At the same time, they’ve emphasized that the investigation is ongoing and that they’re still working to determine exactly where and how spores got into the system. So while Organic West and DFA Fallon are under extra scrutiny, regulators have not issued a final ruling on the specific contamination issue.

From Van Ryn’s vantage point—and many of us can relate—he’s stressing that a positive test in a powder sample doesn’t automatically prove that the milk leaving his farm or any of the 55 farms was the original source. Somewhere between the cow, the tanker, the dryer, the warehouse, and the formula blender, spores found a way in. The job now is to figure out where.

What This Means If Your Milk Goes Into Powder or Infant Products

If you’re one of those 55 farms, or your milk runs into a similar system somewhere else, there’s a tough reality: from a buyer’s or regulator’s vantage point, they see the pool, the plant, and the product more than your individual track record.

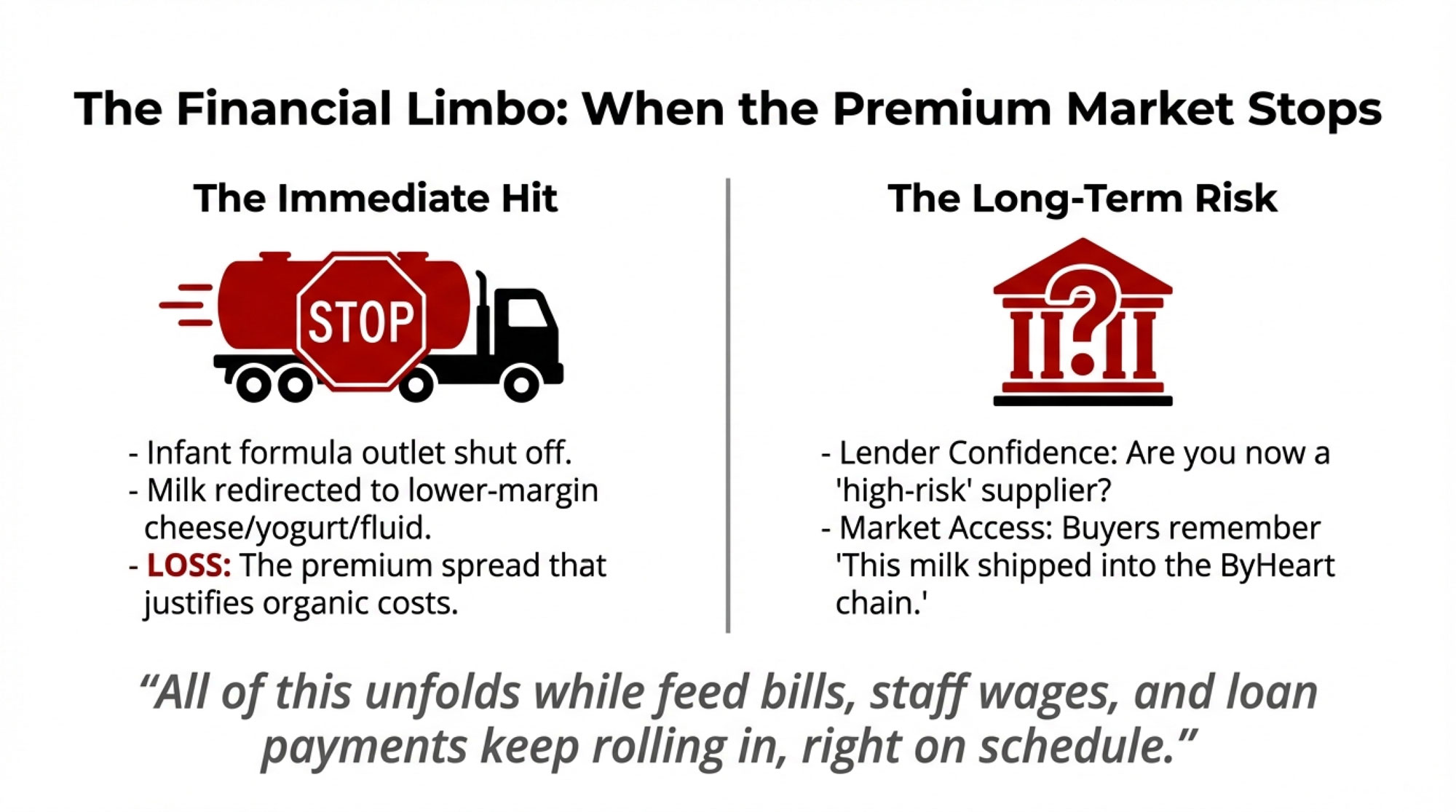

Those farms are still milking. Their organic milk can be redirected into other organic products, such as fluids, cheese, yogurt, and various powders. But that infant formula outlet, which probably helped justify the cost and effort of organic certification and all the detail that goes into feed, dry cow, and transition management in organic herds, is effectively shut off for now. That’s real opportunity cost, even without putting a dollar value on it.

Many Midwest producers will recognize the feeling from other situations: you can be doing a great job on your own place—sound fresh cow programs, strong transition period performance, consistent components—and still get caught up in problems that start at a plant or in another part of the chain. In Wisconsin, for instance, herds shipping to specialty plants have had to live with added oversight because of issues at the plant, even when their own farm tests were clean.

Here, the worry for those 55 families isn’t just this month’s test results. It’s the next lender meeting, the next renewal conversation, the next buyer negotiation. Will lenders and buyers still view them as low‑risk suppliers a year or two from now? Or will there always be a quiet mental note attached: “This milk shipped into the ByHeart chain during the botulism investigation”?

The other piece is premiums. Organic whole milk powder used in infant and specialty ingredient markets generally trades above conventional nonfat dry milk and standard whole milk powder. You don’t need a specific spread to know that losing or clouding that outlet tightens margins. USDA price data and market commentary have consistently shown that organic powders command higher prices than their conventional counterparts; that’s part of why farms put up with the extra requirements.

For some of these families, the question isn’t just about this year’s milk check. It’s whether the farm they hoped to pass on will still be welcome in the highest‑value markets ten years from now.

Four Ripple Effects for Anyone Shipping Into Powder or Infant Ingredients

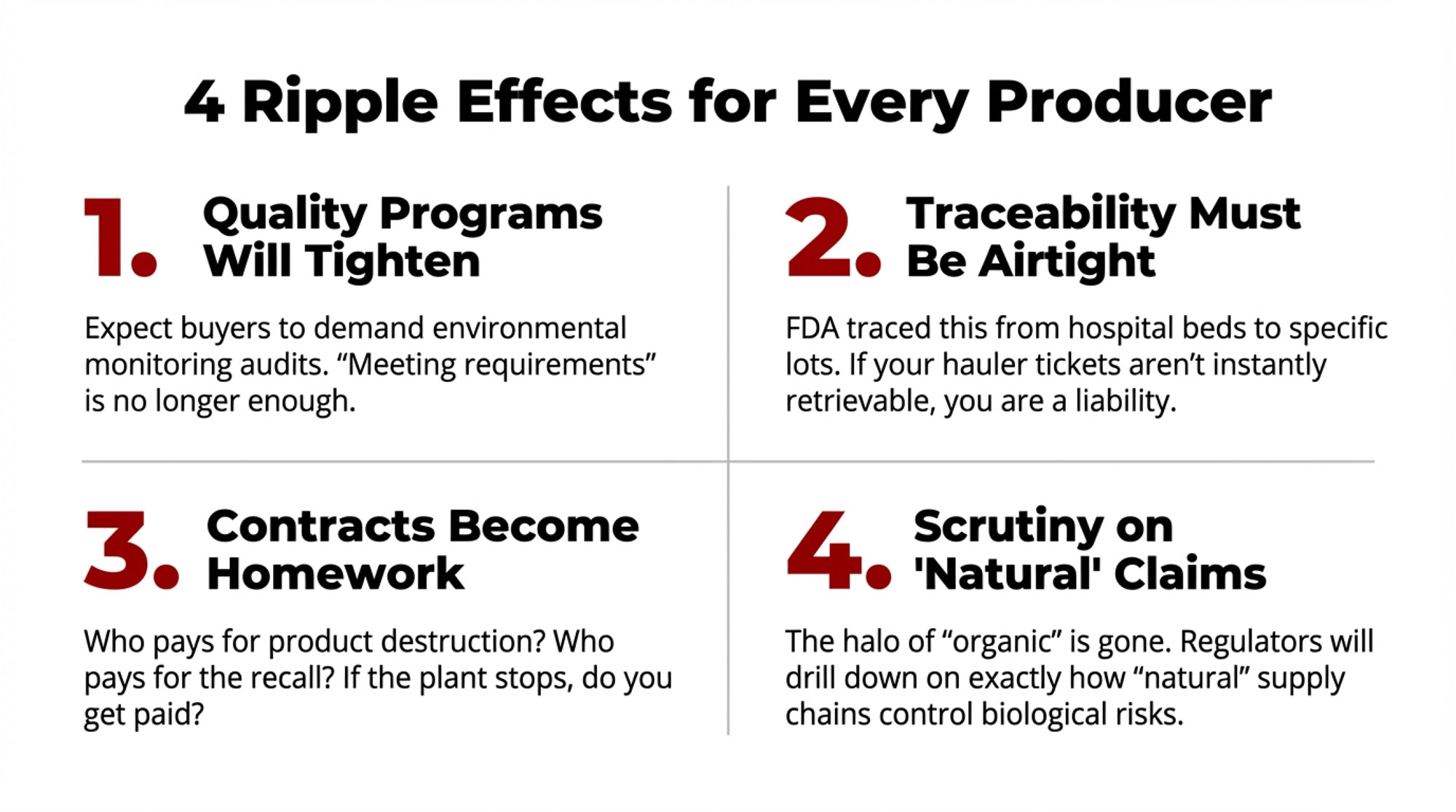

What many of us have seen, watching how the FDA handles food incidents, is that a case like this sends ripples through the entire sector. For anyone whose milk ends up as powder or an ingredient in infant products, four of those ripples matter a lot.

1. Quality Programs Will Tighten

If your milk, or your co‑op’s milk, finds its way into powder that feeds infant or pediatric products, expect more questions. Processors are likely to push harder on:

- How suppliers are approved.

- What documentation is on file.

- Whether there’s any on‑farm testing or extra audits tied to high‑risk outlets.

It’s not about assuming farms are doing something wrong. It’s about buyers understanding that the FDA now has fresh evidence of spores in an ingredient used in a sensitive product, and that everyone in that chain will be scrutinized more carefully next time. They’ll want more than “we meet requirements” when it comes to plant hygiene, environmental monitoring, and escalation when something looks off.

2. Traceability Has to Be Airtight

The work the FDA and CDC have done on this outbreak shows they can trace from hospital beds back to brands, lots, ingredients, and facilities. If your paper trail—hauler tickets, plant receipts, lab results—is scattered across different desks and systems, you’re behind where buyers and regulators are going.

Traceability is the supply‑chain version of watching fresh cows closely in the transition period. When something goes wrong, you need to be able to quickly and clearly see where your milk went and what its quality profile looked like over time. That’s what gives you a fighting chance to show your farm has been doing its part.

3. Contracts and Insurance Will Turn Into Homework

Premium markets bring premium liability. In 2023, the FDA sent warning letters to several infant formula manufacturers, including ByHeart, over Cronobacter control and plant sanitation. Those letters came months after inspections and findings, and during that time, plants and suppliers alike were operating under a cloud.

If your milk is tied into infant or high‑risk ingredient markets, it’s worth pulling your contracts and policies out of the drawer and asking a few blunt questions:

- If there’s a recall, who pays for product destruction and logistics when the dust settles?

- If a buyer has to pause purchases while they deal with regulators, what happens to your milk check during that time?

- Can your co‑op or processor pass legal costs or settlements down to member farms if a case gets ugly?

If your exposure to these markets is modest and your contracts spell out recall and indemnity in a way you can live with, you may decide the trade‑off is acceptable. If a big share of your milk is in these channels and the contract language is vague or one‑sided, that’s a signal to either push for clearer terms or re‑think how much exposure you’re willing to carry.

4. “Organic” and “Clean Label” Will Draw More Scrutiny

One of the ironies here is that this outbreak happened in a brand sold as cleaner and more thoroughly screened than the competition. That doesn’t mean organic or “clean label” is unsafe. But it does mean organic dairies and ingredient plants will feel more scrutiny.

Consumers often treat organic labels as a shortcut for “safer” or “more natural.” When something like this hits the news, retailers, regulators, and parents start asking tougher questions about what’s behind the label:

- How is the supply chain actually controlled?

- What’s different about how these plants manage environmental and spore risk?

Producers in those markets will feel that in the form of more documentation requests, tighter specifications, and, sometimes, more probing conversations with auditors and buyers.

How Long Does This Hang Over a Supply Chain?

Recent infant formula incidents tell us these investigations don’t wrap up in days. They run for weeks or months, from the first cluster of cases through inspections, product sampling, environmental testing, and finally public warning letters or closing summaries.

Here, we’re talking about:

- 51 infants.

- 19 states.

- One branded formula manufacturer, an ingredient plant, and a multi‑farm organic pool.

FDA has said it’s still working to determine whether there’s a common source of contamination and exactly where it sits in the chain. Meanwhile, ByHeart has recalled all its powdered infant formula and told parents not to use it. For everyone connected to that chain, that means living with regulators’ attention until they decide the story is closed.

For the 55 farms shipping to Organic West, that “limbo” looks like talking with lenders, accountants, and family members about what happens if that premium infant formula outlet doesn’t come back soon—or comes back with new requirements and tighter testing. In Midwest and Northeast operations, many folks know that feeling from times when a cheese plant or processor has had a major issue, and everyone in the patron pool has had to live with new testing regimes and contract changes.

All of this unfolds while feed bills, staff wages, and loan payments keep rolling in, right on schedule.

So What Do You Actually Do on Your Farm?

You can’t control the FDA. You can’t control exactly how a plant handles its environmental monitoring. But you can decide how much exposure to these markets you want in your business model, and how prepared you’ll be if your name ever shows up in an investigator’s notes.

Here’s a practical way to think about it.

| LOW Exposure (<10% volume to powder/infant) | HIGH Exposure (>30% volume to powder/infant) | |

| STRONG Documentation (3–5+ years records) | QUADRANT 1: Low Risk, Well-Positioned- Limited downside in recall- Can prove cleanliness to lenders- Premium markets optional- Action: Monitor & maintain | QUADRANT 2: High Exposure, Defensible- Significant premium upside- Can defend farm if investigated- Still vulnerable to plant failures- Action: Review recall liability, add interruption coverage |

| WEAK Documentation (<3 years records) | QUADRANT 3: Low Risk, Under-Prepared- Minimal immediate threat- Can’t prove history if asked- Lender confidence at risk- Action: Build documentation file NOW | QUADRANT 4: HIGH RISK, FLYING BLIND- Major premium exposure + weak defense- Can’t prove cleanliness in investigation- Lender nightmare if recall hits- Action: URGENT—exit infant markets OR fix docs/contracts |

1. Map Your Exposure

Sit down and answer three simple questions:

- Does any of my milk go into powder?

- Does any of that powder end up in infant or pediatric products?

- Roughly what share of my total volume is tied up in those higher‑risk outlets?

If only a small share of your milk flows into these channels and you’re comfortable with your buyer’s programs, you may decide your main job is to keep doing the basics well—milk quality, herd health, clean transition management—and to stay tuned to how your buyer responds to this case.

If a big chunk of your milk—say, a quarter or more—is tied into powder or infant ingredients, it’s reasonable to treat that as a high‑exposure segment of your business. That doesn’t mean you should walk away from it. But it does mean you should spend some time understanding the contracts, insurance, and documentation requirements for that segment.

2. Build a Documentation File You Can Put on the Banker’s Desk

On many farms, lab reports and records are scattered. Some with the vet, some in the co‑op’s system, some on paper in the office. If you’re in sensitive markets, it’s worth pulling that into one place.

A practical target is to be able to show three to five years of:

- Milk quality records (SCC, PI counts, standard screens your buyer runs).

- Any relevant environmental or product test results your processor shares.

- Audit reports if you’re organic or in other quality programs.

Many buyers and insurers are already thinking in multi‑year horizons when they assess risk. If you’re above roughly 30% exposure to powder or infant ingredients and can’t pull together at least three solid years of documentation, it’s a sign you’re in a high‑risk corner of the grid from a paperwork standpoint, even if your day‑to‑day practices are excellent.

3. Read the Contracts You Signed

It’s not fun work, but it’s cheaper to read contracts with a cup of coffee than with a lawyer on the phone.

Look specifically for:

- Indemnity and recall language—who pays for what.

- Suspension clauses—what happens to your milk if purchases are paused.

- Cost‑sharing for legal defense, settlements, or extra testing.

If you find terms that would be devastating for your farm in a worst‑case scenario, that doesn’t necessarily mean you have to bail on the market. But it does mean you should decide whether to:

- Ask for changes or clarifications.

- Limit how much of your volume you expose to that channel.

- Set aside reserves or add insurance to backstop that risk.

| Contract/Insurance Question | ✓ Good Answer (Protects Farm) | ✗ Dangerous Answer (Exposes Farm) | Where 55 ByHeart Farms Likely Stood |

| 1. Who pays for product destruction in recall? | Processor/co-op covers; farm only liable if proven source | Farm pays pro-rata, regardless of fault | Likely pro-rata = liable even if not at fault |

| 2. What happens to milk check if plant pauses purchases? | Continued payment or alternate outlet guaranteed | Payments suspended until investigation ends | Likely suspended = lost income for months |

| 3. Recall liability cap per farm? | Yes—exposure capped at $X or Y months revenue | No cap; farm liable for full recall costs | Likely no cap = unlimited downside |

| 4. Legal defense costs covered? | Co-op provides defense at no cost to farm | Farm pays own legal costs | Likely farm pays = $50K–$200K bill |

| 5. Business-interruption insurance? | Yes—lost revenue covered if outlet shuts | No coverage; farm absorbs margin loss | Likely no coverage = 100% margin loss |

| 6. 3rd-party audits & environmental testing required? | Yes—buyer funds regular audits | No specific testing; “meet standards” | Unknown—if not required, no leverage |

| 7. Can buyer terminate during investigation? | Termination requires proof of farm contamination | Buyer can suspend/terminate “for cause” | Likely broad rights = instant cutoff |

| 8. Contamination liability insurance mandated? | Contract requires $1M–$5M minimum coverage | No insurance required; farm assumes all | Likely no mandate = self-insuring unknowingly |

This is the fine print your lender and insurer will want to understand if something goes sideways.

4. Talk With Your Insurer Like a Risk Partner

Make sure your agent understands:

- That some of your milk may be going into powder and possibly infant products.

- What coverage do you have for product recall, contamination, and business interruption tied to food safety issues.

Ask directly: “If my milk ends up being part of an investigation—even if it’s never proven to be the source—how would this policy respond?” Better to have that conversation now than in the middle of a crisis.

5. Decide How Far You Want to Go on Extra Testing

Some farms, especially larger ones with significant exposure to infant ingredient markets, may decide to partner with their buyer on additional testing or environmental monitoring. That can:

- Strengthen your position with risk‑sensitive buyers.

- Give you more data about what’s happening in your part of the chain.

But it also:

- Costs time and lab money.

- Can raise tough questions if the results are borderline, even when you’ve done nothing wrong.

There’s no universal right answer. It comes down to your scale, your markets, your tolerance for risk, and your relationship with your processor.

The Trade-Off You Can’t Dodge

For Bill Van Ryn and those 55 organic families, the coming months will determine whether they’re remembered as farms that got swept up in a rare supply‑chain event or as the case everyone points to when they talk about infant formula risk. In the meantime, they’re still doing what all of us do: milking cows, managing fresh cow groups, balancing rations for butterfat and components, and keeping up with bills and certifications.

If your milk runs into similar pipelines, your real decision isn’t whether risk exists. It’s whether you want that risk as part of your business model—and, if you do, how intentional you’re going to be about managing it.

Staying in high‑value powder and infant markets usually means better pricing than a generic blend check, but it also brings more paperwork, more questions, and more eyes on your operation and your buyer’s plant. Stepping away from those markets means giving up some upside but also sleeping a bit easier when you read stories like this.

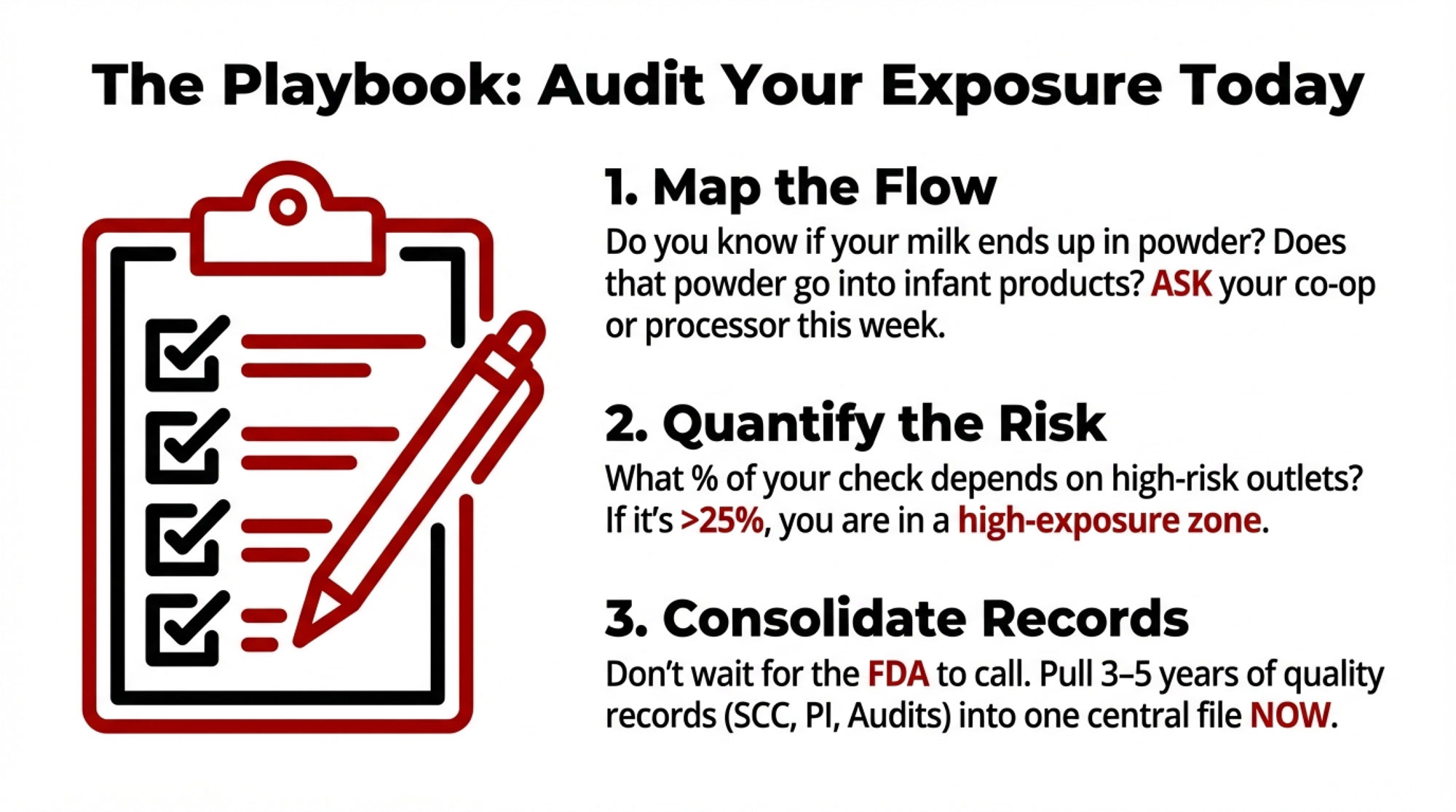

So if you only have time for a short checklist over coffee, here’s where to start in the next 30 days:

- Find out exactly how much of your milk ends up as powder or infant/pediatric products, and through which plants.

- Sit down with your processor and insurer to walk through contracts, recall liability, and coverage tied to food safety events.

- Pull your lab and audit records into one place, so you’re not scrambling if someone asks for them under pressure.

You don’t need to panic. But you do need to decide how much of this risk you’re willing to own—and then build your playbook around that choice.

At the end of the day, a ‘Clean Label’ doesn’t protect your equity—only a clean contract does. Don’t wait for the FDA to audit your life; audit your own risk before the next tanker pulls into the yard.

Key Takeaways

- 51 babies, 19 states, one ingredient: FDA found botulinum toxin in ByHeart infant formula and in the organic whole milk powder used to make it—the entire supply chain is now under investigation.

- 55 organic farms in one pool, all under the same microscope: Milk from certified organic dairies flows through Organic West to DFA’s Fallon, Nevada plant, then into ByHeart’s premium formula. One positive test implicates them all.

- Spores survive what kills most pathogens: Clostridium botulinum spores can persist through pasteurization and spray-drying—standard milk quality programs aren’t designed to catch this risk.

- Contracts, premiums, and lender confidence are all on the table: Expect tighter traceability, tougher quality audits, more complex recall and indemnity language, and sharper scrutiny of organic and “clean label” claims.

- Your 30-day playbook: Map your milk’s path into powder and infant products, consolidate 3–5 years of quality and audit records, review contract recall clauses, and sit down with your insurer about contamination and business-interruption coverage.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Don’t Get Burned: The Producer’s Guide to Negotiating Watertight Milk Contracts – Exposes the lethal fine print in modern supply agreements and delivers a step-by-step negotiation framework. Use these tactics to shield your equity from lopsided recall liabilities before the next market disruption hits your milk check.

- The Bullvine Dairy Curve: 15000 U.S. Farms by 2035 and Under 10000 by 2050 – Who’s Still Milking? – Breaks down the brutal math of industry consolidation and reveals why specialized ingredient pipelines are the only remaining life raft for mid-sized herds. This analysis arms you with the strategic clarity needed to pick the right side of the survival curve.

- The $50,000 Biofilm Crisis Your ATP Test Will Expose – Reveals how hidden pathogen reservoirs in your equipment bypass standard wash cycles and identifies the advanced monitoring tools that catch them. Mastering this tech prevents catastrophic grade-outs and secures your reputation as a top-tier supplier in high-scrutiny markets.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!