Ever notice a yard slipping and barn lights burning late on your road? This piece is your playbook for when to turn in—and how to actually help.

Executive Summary: This article tackles a reality most dairy families know too well: in the stress storm of high costs, tight margins, and rising interest, it’s not just the cows that are tired—farmers are too. It shows how early warning signs on a road—yards slipping, familiar faces missing from meetings, kids quietly stepping back from 4‑H—often show up long before a herd is listed for sale. Through five “quiet ways” neighbours step in, from one honest question in the lane to trucks in the yard, shared showstrings, and farmer‑focused hotlines and workshops, the story maps out how community support buys producers something priceless: enough breathing room to think clearly. It draws a straight line between that breathing room and better decisions on genetics, culling, expansion, succession, and staying in the game when panic could easily push a family out. For readers, it doubles as a practical playbook—how to spot when a neighbour’s in trouble, what actually to offer, and when to make the call for outside help. At its core, the piece argues that in dairy, the roads where people refuse to let each other fall alone are the roads most likely to keep their barns, families, and options alive.

I’ll never forget a kind of late‑winter morning on a dairy farm when the mud in the lane felt about as deep as the weight on your chest. The truck still came, the cows still milked, the chores still got done, but every step cost more than it used to—mentally, physically, and financially. If you’re milking cows in these mid‑2020s, with higher input costs, tight margins, and interest rates that climbed faster than most of us ever planned for, you don’t need anyone to explain “farm stress” to you. You’re living it.

This story is for the barns where the lights have been on a little later, a little more often. It’s about how dairy neighbours quietly keep families and herds on their feet when the load gets heavy—and what that kind of support really means for your decisions, your genetics, and your odds of still shipping milk five or ten years from now.

1. When Stress Starts Showing Up in the Yard

There’s a stretch on almost every road where, one winter, you notice a yard that doesn’t look quite like it used to. The place is still run, the cows are still well cared for—but the shine is off.

The ration sheets on the fridge haven’t been updated in a while. The nutritionist still stops in, but some days there just isn’t any energy left to talk about tweaking butterfat or tightening up fresh‑cow routines. A vet comes out for a DA or a rough calving and, walking back to the truck, quietly clocks that the barn isn’t as sharp and tidy as it was when everyone in that family had a bit more gas in the tank.

You see it in people, too. The neighbour who never missed morning coffee at the diner stops showing up. The 4‑H parent who used to be first to put their hand up for a committee starts missing meetings because the days have simply gotten too long. Kids lean into off‑farm shifts more, trying to help with bills or just needing a bit of breathing room from the constant pressure at home.

Over the last decade, Canadian research led by veterinarians and epidemiologists at the University of Guelph has found what many of us already sensed: farmers are carrying higher levels of stress, depression, anxiety, and burnout than the general population. Those national surveys, published since 2016, put numbers behind what you can see with your own eyes at co‑op meetings and in sale barns. Financial pressure and workload consistently emerge as core stressors.

| Condition | Farmers (%) | General Pop (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Stress/Burnout | 48 | 22 |

| Depression | 18 | 8 |

| Anxiety | 22 | 10 |

What’s important—and hard to admit—is how this stress seeps into decisions. When you’re worn down, you’re more likely to make short‑term, “just get through this month” choices that can haunt your herd and your balance sheet for years. Panic‑selling heifers and shrinking your future genetic base. Skipping critical maintenance until something fails at exactly the wrong moment. Letting a workable succession plan sit in a drawer because you’re simply too exhausted to push through one more tough conversation.

If you’re watching a place where the yard is slipping, meetings are being missed, and kids are quietly stepping out of calf club or 4‑H for a season, and that pattern runs for a month or two, that’s not just “they’re busy.” That’s your red flag. Whether it’s your yard or your neighbour’s, that’s the moment to treat stress as a management factor with real consequences, not just a feeling you’re supposed to tough out alone.

2. The Question in the Lane That Changes Everything

There’s a kind of moment in the lane that doesn’t make it into any ledger, but it can change the whole story.

Picture this: the vet’s truck pulls in on a cold, grey morning. There’s a fresh cow that didn’t bounce back, a calving that went sideways, a calf that needs more help than a bottle and a towel. They do what needs doing, get the cow settled, calves treated, parlour moving again. On paper, that’s the job done.

But then the vet and the producer walk back to the truck through the ruts and slush. The vet leans on the door instead of climbing in, takes a good look, and says something simple like, “You look worn out. How are you really holding up?” And then doesn’t say anything else for a bit.

That pause can feel longer than a dry spell in August. Answering it honestly takes more courage than most of us give ourselves credit for. Admitting you’re bracing every time the phone rings. That the bills, breakdowns, staff worries, and short nights have piled higher than you know how to manage. That you’re starting to question what else you’ve got left in the tank.

Across Canada, mental health literacy programs built for agriculture—like the “In the Know” workshops offered through Agriculture Wellness Ontario and CMHA—are trying to give people more tools for exactly this moment. They’re free, four‑hour sessions tailored to farmers and farm families that cover stress, depression, anxiety, substance use, and how to start conversations around mental health, using real farm examples and facilitators who understand agriculture. They don’t make the problems disappear, but they do help neighbours, vets, nutritionists, and co‑op reps feel more prepared to ask that question and hear the answer.

On your road, it often comes down to this:

- If you’re the vet, nutritionist, field rep, or neighbour, you’re close enough to see when the wheels are starting to wobble. One honest question in the lane can be the difference between a neighbour making huge, permanent decisions in a fog and getting just enough space to think clearly again.

- If you’re the one being asked, treating that question as an opening—not a judgment—can be the step that buys you time and options you simply won’t have if you keep white‑knuckling it by yourself.

You’d never ignore a cow that’s been off feed for three days. You shouldn’t ignore the human version of that in your own yard either.

3. The First Call Down the Road

What happens after that question in the lane usually isn’t a formal family meeting or a big public moment. It’s much quieter.

It might be after evening milking. The cows are fed, the parlour is washed up, and the kitchen light is the only one still on. Someone in the family finally says, “We can’t keep doing this on our own,” and they reach for the phone. They don’t call an office. They call one person on the road who understands cows, bills, and pride.

On the other end, that neighbour has already noticed the late barn lights and the empty chair at the co‑op meeting. They pick up, listen, let the silence sit for a beat, and say something like, “I’ll swing over. Put the coffee on.” No big speeches. Just a quiet promise: “You don’t have to carry this by yourself tonight.”

They sit at the table in coveralls, boots still muddy, hands wrapped around mugs that have been reheated too many times already that day. They talk about the calf that didn’t make it. The feed bill that landed the same week the milk cheque was light. The interest reset that blew the budget wide open. The feeling that no matter how hard they push, they’re always one step behind.

The markets don’t magically improve during that coffee. The numbers on the balance sheet don’t change. But the weight shifts a little. The load sits on two sets of shoulders instead of one.

From a herd owner’s point of view, that quiet visit does a few powerful things:

- It lowers the odds you’ll make a big, irreversible decision on a bad afternoon—slashing into your heifer pen, walking away from an improvement plan, or writing off an expansion that still makes sense on paper if you look at it with a clear head.

- It opens the door to specific, practical offers of help that can free up a bit of time and mental space so you can actually look at your SCC, butterfat, Net Merit, or LPI, debt load, and contracts instead of just reacting to the next fire.

- It sets a pattern on the road. Once one family makes that call and survives it, it gets easier for the next one to pick up the phone when their turn comes.

If you’re the neighbour noticing the changes—yard slipping, meetings missed, kids disappearing from the ring for a season—don’t wait until the auction posters show up. Call when you’ve seen those patterns for a month or two. And if you’re the one doing the disappearing, treat that as your own warning light. The earlier that first call happens, the more steering room you’ve got.

4. When Help Shows Up in Trucks and Coveralls

Nobody expects a Hollywood moment where they look out the farmhouse window and see a whole parade of tractors magically lined up in the lane. Real neighbour help usually arrives in beat‑up pickups and chore clothes.

Sometimes it’s a neighbour who pulls in on a Saturday morning with a skid steer and says, “Let’s clean this lane up and move a few gates so this calving pen’s easier to work in.” Sometimes it’s someone offering to run the TMR for a couple of mornings so the family can catch up on sleep, paperwork, and phone calls they’ve been avoiding. On some roads, there’s still that retired dairyman who quietly shows up to feed calves a few times a week, because he knows half an hour in the calf barn can buy someone else a badly needed breather.

There’s always a cost to this kind of help. If you’re the one stepping in, you’re giving up time you could spend tweaking your own ration, pushing your repro numbers, or wrestling with your own paperwork. The cows at home still need you. The numbers at home still matter.

| Impact Category | Per Herd Loss (250–300 cows) | Route-Level Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Annual Milk Volume Lost | ~2.1M–2.4M lbs/year | Route density drops; processor may rationalize pickups or consolidate drop points |

| Semen/Embryo Market | $8K–15K/year in genetics purchases gone | Local AI techs lose calls; breed association loses dues-paying member |

| Show Calves & Genetics Demand | 2–4 show heifers + sale genetics annually | Calf club, 4-H, and ring activity thins out; next-generation breeders lose mentorship |

| Neighbor Labor & Equipment Sharing | 50–100 hrs/year of informal help | Remaining farms must absorb chores, maintenance cover; service density declines |

| Co-op & Industry Participation | 1 seat at board, 1 vote, herd improvement days, meetings | Governance weakens; knowledge-sharing networks shrink; institutional memory lost |

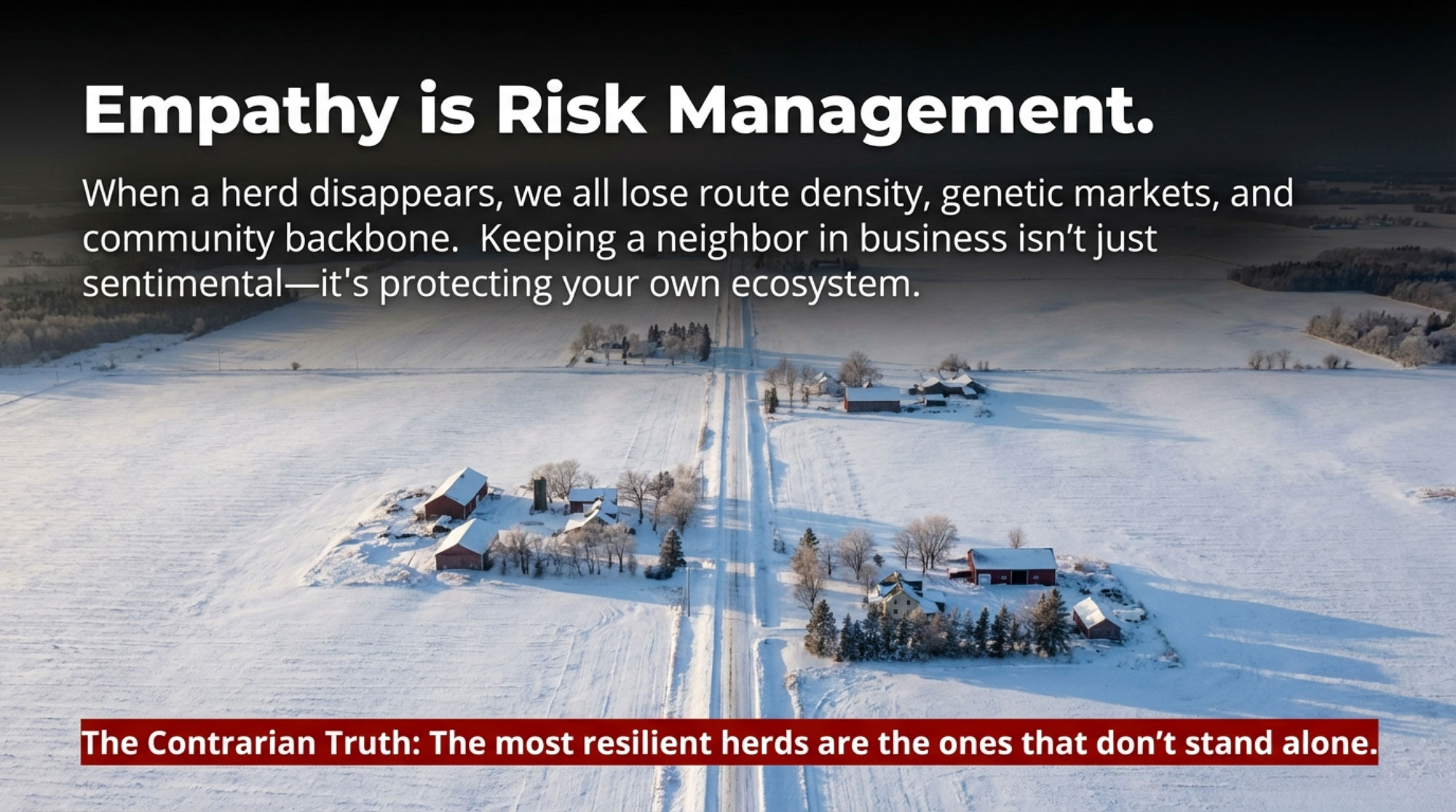

But when too many solid mid‑sized herds on a road disappear, everyone pays a different price.

| Scenario | Year 1 Cost / Benefit |

|---|---|

| Community Support Path (neighbor help, mental health resources, quiet advice) | ~$5K–8K in informal labor + counseling costs (partner time, mileage) = Better decision-making, herd stays, genetics preserved, route density maintained |

| Isolation / Crisis Path (farmer panics, culls too hard, sells out, or enters bankruptcy) | $50K–200K+ in liquidation costs, legal fees, lost milk revenue, replacement heifer loss, family stress + off-farm transition costs + route disruption |

When a well‑run herd sells out, it isn’t just one family losing their way of life. There are fewer litres on the truck route, which can make it easier for a plant to talk about rationalizing pickups or shifting where milk goes. There’s one less herd buying semen, embryos, and show heifers, one less family filling seats at herd improvement meetings, one less barn where kids learn to fit calves for the ring. You lose part of the local market for genetics and part of the backbone of the community that stands behind you when you’re taking big swings with robots, genomics, or expansion.

You’ll never see “neighbour labour” as a line item on your cost‑of‑production report. But if you’re thinking like a long‑term owner instead of just a day‑to‑day survivor, those hours in someone else’s barn are part of your own risk‑management plan. A little extra effort today might be cheaper than losing another good herd on your route—and the choices that disappear with it.

5. The Ring, the Hall, and the Places That Hold Us Together

Sometimes the first sign that a family is slowly climbing back out of a rough stretch doesn’t show up in the barn at all. It shows up where dairy people still gather.

You might notice it at a spring calf club meeting when a kid who stepped back for a year walks in, leading a heifer. The calf might be a little green, the kid a little nervous, but they’re there. Or you see it at a local show when a family that’s been through a tough season pulls into the grounds with just one animal on the trailer instead of a full string—and half the barns quietly realize what it took for them to get there.

What moves people most in those moments isn’t the quality of the calf or the color of the ribbon. It’s knowing the hours that went into getting chores done at home, the rides quietly arranged, the clipping help offered in the last hour before loading. It’s the way parents watch their kids in the ring, and you can see, in their faces, that being back in that barn with their community is worth every ounce of extra effort.

Show barns, church halls, co‑op board rooms, auction markets, and small‑town coffee corners might not look like “support hubs” on a map, but that’s what they are in a lot of dairy regions. Deals and decisions get made quietly at the back of a sale ring or over a cup of coffee:

“We’ll cover your evening chores so you can get your dad to that appointment.”

“Drop your kids here if you’re still at the parts counter when school gets out.”

“We’ve got room on the trailer if you decide that calf should go.”

Those choices don’t change your cwt price or butterfat premium overnight. But they keep families and kids connected to the parts of dairy that feed their hearts—4‑H meetings, shows, herd improvement days—instead of letting their world shrink down to nothing but bills, breakdowns, and stress.

If you care about your herd’s future—about who’s going to buy your embryos, run your cows through the ring, or stand beside you when you’re deciding how hard to lean into robots or genomics—you want those gathering places to stay alive. That’s where the next generation of breeders, show‑string managers, and herd owners are building the relationships that quietly decide who survives consolidation and who doesn’t.

The Kind of Support You’ll Never See on a Milk Cheque

Sit through a couple of winter producer meetings or Saturday sale days and really listen, and you’ll hear the same quiet truth in different words: there were stretches a lot of folks might not have made it through without help from the road. They may not spell it out, but it’s there in the way someone says, “We had some neighbours show up when it got rough,” or “The kids at 4‑H kept us going that year.”

This isn’t a neat story. Families still open ugly envelopes in the mailbox. Cows still choose the worst night of the month to need a C‑section. There are mornings when the mixer breaks, the calf scours, and the parts truck is delayed, all on the same day the banker’s coming. Some kids look at what their parents are carrying and honestly wonder if they want that future for themselves.

Not every road or community responds the same way. Some barns are too far apart for quick drop‑ins. In some areas, most people are working full‑time off‑farm, and there just aren’t many extra hands or hours to give. Pride and privacy still keep good people from speaking up until they’re closer to the edge than anyone’s comfortable with.

At the same time, the support around farmers is slowly shifting. Mental health literacy workshops like “In the Know” are giving producers, vets, field staff, and neighbours shared language and simple tools for talking about what they’re seeing and feeling. In the U.S., the Farm Aid hotline—1‑800‑FARM‑AID—connects farmers with staff who understand agriculture and can help sort through financial, legal, and personal stress in English or Spanish, and link them with local resources. In Canada, the Do More Agriculture Foundation keeps an updated list of crisis lines, counselling options, and other supports tailored to farm life, so producers don’t have to start from scratch when they finally decide to reach out. In many provinces and states, agriculture ministries, CMHA branches, extension services, and farm groups are standing up dedicated rural and farm‑focused lines and programs.

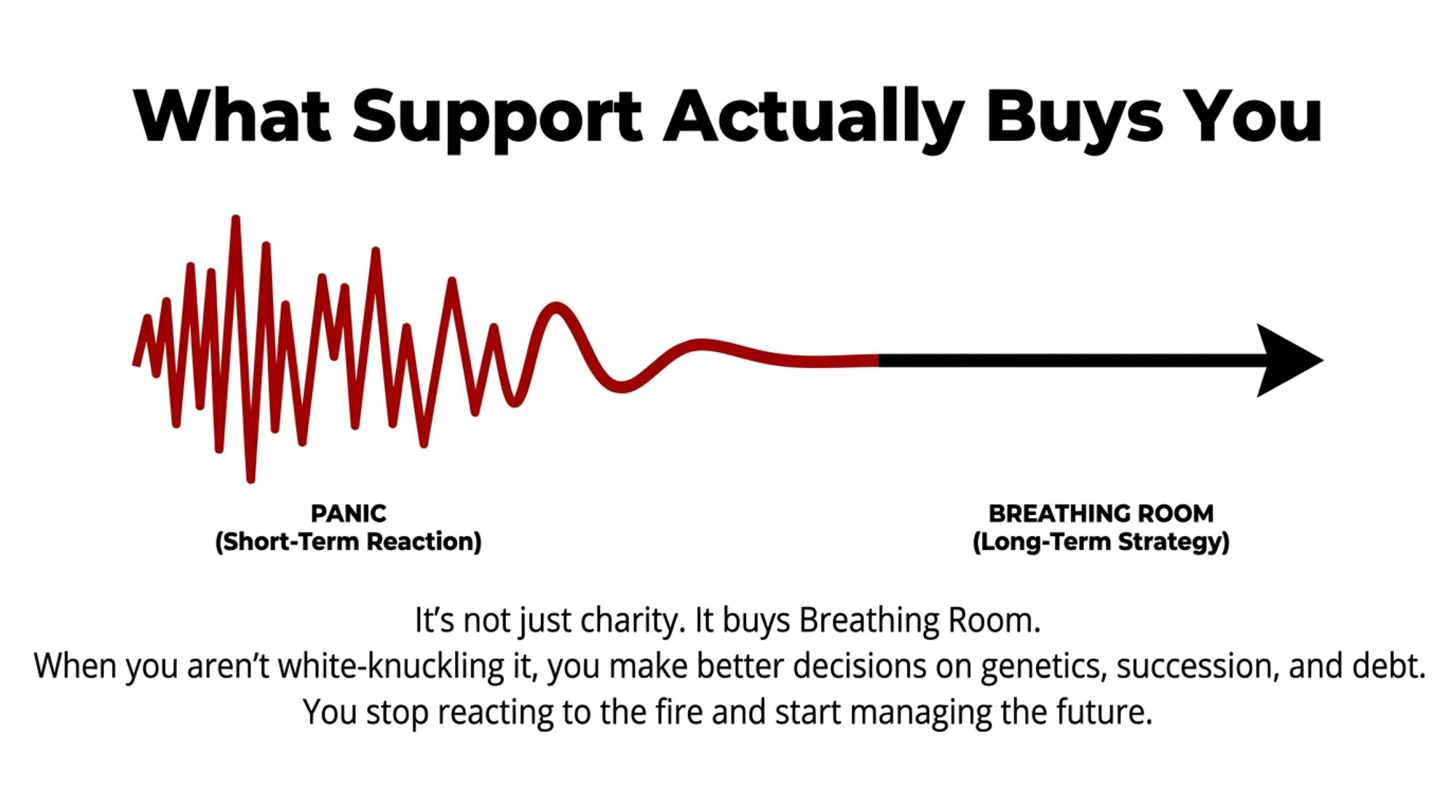

Support doesn’t magically fix milk price, interest rates, or feed costs. But here’s the practical side of all this:

- When stress is driving your day, you’re more likely to make rushed calls on genetics, culling, expansion, or exit that feel necessary in the moment but leave you with fewer options later.

- When neighbours, staff, family, and structured programs give you even a bit more breathing room, you’ve got a better shot at looking at your SCC, components, Net Merit or LPI, debt, and contracts with a clear head—and that’s when you make stronger decisions.

You won’t see “time to think clearly” on your milk statement. But it shows up in whether your herd, your family, and your community still have choices tomorrow.

| Support Resource | Phone / Contact | Availability | What They Do | When to Call |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-800-FARM-AID(U.S.) | 1-800-327-6243 | 24/7 | Farm financial counseling, legal referrals, local resource matching (English/Spanish) | Financial crisis, debt panic, legal questions about farm viability |

| Do More Agriculture Foundation(Canada) | Website: domore.ag | 24/7 directory | Curated list of crisis lines, counseling, peer support by province; updated monthly | Need Canadian-specific mental health or crisis support in your province |

| CMHA Mental Health Crisis Line(Canada) | 1-833-456-4566 (national) | 24/7 | Trained peer/professional support for acute mental health crisis; referrals to local counseling | Suicidal ideation, acute anxiety/panic, feeling unsafe or stuck |

| Agriculture Wellness Ontario | “In the Know” workshops (free) | Seasonal (winter focus) | 4-hour peer-led mental health literacy + farm stress training for producers, vets, staff | Ready to learn tools before crisis; want to help neighbors recognize signs |

| Your Land-Grant University Extension (e.g., Guelph Vet Med) | Search: “[Your State/Province] Dairy Extension” | Seasonal (high during crisis) | Farm crisis counseling, financial planning, herd transition support; often free or sliding scale | Need on-farm problem-solving; debt/succession planning; herd health during stress |

What This Really Means on Your Farm

Let’s bring this right back to your kitchen table.

- Stress is a management factor, not just a feeling.

You’d never ignore a rising SCC, dropping repro, or slipping butterfat because “the truck’s still coming.” Stress changes your judgment the same way those numbers change your milk cheque. It deserves the same level of attention. - Community support belongs in your risk‑management plan.

Roads where people quietly show up for each other give everyone more room to make decisions based on long‑term herd health and equity, not panic and exhaustion. - You’re on both sides of this story.

You’re the neighbour who can spot when someone else is sliding, and you’re also the owner who has to admit when your own barn feels heavier than it should. In both roles, small, specific actions—a call, a visit, an offer to feed calves or haul a calf—do more than big speeches.

If you want a simple rule of thumb, try this: “Will this action give me or my neighbour more ability to make a clear, long‑term decision, or less?” If the answer is “more,” it’s almost always worth your time.

A Quiet Playbook: 5 Ways to Show Up

If you’re reading this between chores and just need the core playbook, here’s a simple five‑step way to think about it.

- Watch for the patterns, not just one bad day.

When a normally tidy yard starts slipping, a familiar face disappears from meetings, or a kid quietly steps back from 4‑H or calf club for a season, don’t just shrug it off. If you see several of those changes over a month or two, treat it as a sign that the load might be too heavy, not just “they’re busy.” - Ask one honest question.

In the lane, beside the bulk tank, or at the back of the sale barn, a simple “How are you really holding up?” can open more doors than you’d expect. Ask it once, then leave enough silence for a real answer to land. - Offer one concrete piece of help.

“If you need anything, call” almost never leads to an actual call. “We can feed calves Wednesday night,” “I’ll run your TMR for a couple of mornings,” or “We’ll haul that calf to the show with ours” are offers people can realistically say yes to. Those small bits of help buy time, and time buys better decisions. - Keep one solid support contact handy.

Have at least one farmer‑focused support number written down—a provincial wellness or crisis line, a trusted rural counselling service, or a number like 1‑800‑FARM‑AID. If a conversation ever turns serious and you’re worried about someone’s safety or about how stuck they feel, that’s when you use it. - Check your own barn lights, too.

If you’re dodging calls, skipping the places you used to catch up with other producers, putting off meetings with your banker or nutritionist, or just standing longer than usual in the parlour doorway because you don’t feel like starting, treat that as your own warning sign. Talk to a neighbour, a partner, a vet, or a professional now—before the choices get narrower and harder.

| Warning Sign | What It Signals | Timeline | Your First Move |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yard neglect: gates not closed, lane/driveway rough, fencing deferred | Energy and focus dropping; deferred maintenance snowballing | 2–4 weeks of decline | Stop by. Offer to help with one specific job (e.g., “I’ll help you fix that gate Saturday”) |

| Nutritionist/vet visits drop off or get rescheduled | Either cash flow tightening OR mental load too high to engage | 4–6 weeks | Ask: “How are your calls with the nutritionist going?” Listen for hesitation. |

| Familiar face misses co-op, meeting, or morning coffee | Social withdrawal + isolation starting; stress compounding alone | 1–2 missed meetings | Text or call: “I noticed you missed [event]. Everything okay?” |

| Kids step back from 4-H, calf club, or show prep | Family is conserving emotional/financial energy; kids sensing parental stress | 1 season | Don’t judge. Quietly ask: “The kids still interested in showing this year?” Offer trailer help if yes. |

| Herd management gets visibly looser | Decision fatigue and burnout showing in daily care and culling choices | 2–3 months | “Your SCC’s been up a bit—anything I can help troubleshoot?” (Opens door without alarm.) |

When You Notice the Barn Lights on the Way Home

The next time you’re driving home from town after picking up parts or dropping off samples, pay attention to the barns along your route. Notice which yards look a little rougher than they used to, and which barns still have lights burning long after they’d normally be out.

You can keep rolling and tell yourself you’ll stop in “one of these days.” Or you can turn into the lane and sit at the kitchen table for half an hour, even if it means your own chores run a bit later. You don’t have to have all the answers. You just have to be willing to show up.

There’s no bonus line on the milk cheque for being that neighbour. But there’s a quiet strength in roads where people refuse to let each other fall alone—a community that shares genetics, equipment, and labour, and also shares grief, stress, and the stubborn kind of hope that shows up as a truck in the yard when you didn’t even ask.

You can save yourself an hour today by driving past those barn lights. Or you can invest that hour in helping keep another good herd—and your own future options—on steadier ground.

And if the day ever comes when you’re the one staring out at a muddy lane, a stuck tractor, and a stack of bills, there’s a good chance you’ll be deeply grateful that someone else on that road once chose to turn into your lane instead of just driving by.

Key Takeaways

- Watch for early patterns, not just one bad day: a yard slipping, a familiar face missing from meetings, a kid quietly stepping back from 4‑H for a season—those are red flags, not just “busy.”

- One honest question (“How are you really holding up?”) or one concrete offer (“I’ll run your TMR Wednesday morning”) can give a neighbour enough breathing room to make clear decisions instead of panic moves.

- Community support is risk management: every good herd that stays on the road protects route density, genetics demand, and the local network everyone depends on.

- Know one farmer‑focused support line before you need it—like 1‑800‑FARM‑AID in the U.S. or a provincial crisis contact through Do More Ag in Canada—so you’re not scrambling if a conversation turns serious.

- The roads where people turn into the lane instead of driving past are the roads most likely to keep their barns, families, and options alive.

Continue the Story

- The Last Light on the Road: How Wisconsin’s Dairy Communities Keep Showing Up – Walking a similar path, this profile takes us into Wisconsin barns where the community refuses to let the lights go out. It proves that whether in Ontario or the Midwest, the heartbeat of dairy remains the neighbors who show up.

- When the Wells Failed, the Neighbours Didn’t: What Vermont’s $18 Million Drought Showed Us All – Shaped by the same forces mentioned in our profile, this deep dive into the Vermont drought proves the point that crisis is often where community is born. It uncovers the grit required when the wells and the cheques both run dry.

- The Urban-Rural Divide: What Farmers Need to Know About the Mental Health Crisis Reshaping Agriculture – Carrying the story forward, this piece examines how the mental health crisis is reshaping our industry’s culture. It highlights a new generation bridging the divide to ensure the next chapter of dairy is built on resilience, not just production.